Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The World and the Door

The World and the Door

by O. Henry

A favourite dodge to get your story read by the public is to assert that it is true, and then add that Truth is stranger than Fiction. I do not know if the yarn I am anxious for you to read is true; but the Spanish purser of the fruit steamer El Carrero swore to me by the shrine of Santa Guadalupe that he had the facts from the U.S. vice-consul at La Paz—a person who could not possibly have been congnizant of half of them.

As for the adage quoted above, I take pleasure in puncturing it by affirming that I read in a purely fictional story the other day the line: “ ‘Be it so,’ said the policeman.” Nothing so strange has yet cropped out in Truth.

When H. Ferguson Hedges, millionaire promoter, investor and man-about-New-York, turned his thoughts upon matters convivial, and word of it went “down the line,” bouncers took a precautionary turn at the Indian clubs, waiters put ironstone china on his favourite tables, cab drivers crowded close to the curbstone in front of all-night cafés, and careful cashiers in his regular haunts charged up a few bottles to his account by way of preface and introduction.

As a money power a one-millionaire is of small account in a city where the man who cuts your slice of beef behind the free-lunch counter rides to work in his own automobile. But Hedges spent his money as lavishly, loudly and showily as though he were only a clerk squandering a week’s wages. And, after all, the bartender takes no interest in your reserve fund. He would rather look you up on his cash register than in Bradstreet.

On the evening that the material allegation of facts begins, Hedges was bidding dull care begone on the company of five or six good fellows— acquaintances and friends who had gathered in his wake.

Among them were two younger men—Ralph Merriam, a broker, and Wade, his friend.

Two deep-sea cabmen were chartered. At Columbus Circle they hove to long enough to revile the statue of the great navigator, unpatriotically rebuking him for having voyaged in search of land instead of liquids. Midnight overtook the party marooned in the rear of a cheap café far uptown.

Hedges was arrogant, overriding and quarrelsome. He was burly and tough, iron-gray but vigorous, “good” for the rest of the night. There was a dispute—about nothing that matters—and the five-fingered words were passed—the words that represent the glove cast into the lists. Merriam played the rôle of the verbal Hotspur.

Hedges rose quickly, seized his chair, swung it once and smashed wildly down at Merriam’s head. Merriam dodged, drew a small revolver and shot Hedges in the chest. The leading roysterer stumbled, fell in a wry heap, and lay still.

Wade, a commuter, had formed that habit of promptness. He juggled Merriam out a side door, walked him to the corner, ran him a block and caught a hansom. They rode five minutes and then got out on a dark corner and dismissed the cab. Across the street the lights of a small saloon betrayed its hectic hospitality.

“Go in the back room of that saloon,” said Wade, “and wait. I’ll go find out what’s doing and let you know. You may take two drinks while I am gone—no more.”

At ten minutes to one o’clock Wade returned.

“Brace up, old chap,” he said. “The ambulance got there just as I did. The doctor says he’s dead. You may have one more drink. You let me run this thing for you. You’ve got to skip. I don’t believe a chair is legally a deadly weapon. You’ve got to make tracks, that’s all there is to it.”

O. Henry

(1862 – 1910)

The World and the Door

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Henry, O.

A False Start

A False Start

by Arthur Conan Doyle

“Is Dr. Horace Wilkinson at home?”

“I am he. Pray step in.”

The visitor looked somewhat astonished at having the door opened to him by the master of the house.

“I wanted to have a few words.”

The doctor, a pale, nervous young man, dressed in an ultra-professional, long black frock-coat, with a high, white collar cutting off his dapper side-whiskers in the centre, rubbed his hands together and smiled. In the thick, burly man in front of him he scented a patient, and it would be his first. His scanty resources had begun to run somewhat low, and, although he had his first quarter’s rent safely locked away in the right-hand drawer of his desk, it was becoming a question with him how he should meet the current expenses of his very simple housekeeping. He bowed, therefore, waved his visitor in, closed the hall door in a careless fashion, as though his own presence thereat had been a purely accidental circumstance, and finally led the burly stranger into his scantily furnished front room, where he motioned him to a seat. Dr. Wilkinson planted himself behind his desk, and, placing his finger-tips together, he gazed with some apprehension at his companion. What was the matter with the man? He seemed very red in the face. Some of his old professors would have diagnosed his case by now, and would have electrified the patient by describing his own symptoms before he had said a word about them. Dr. Horace Wilkinson racked his brains for some clue, but Nature had fashioned him as a plodder—a very reliable plodder and nothing more. He could think of nothing save that the visitor’s watch-chain had a very brassy appearance, with a corollary to the effect that he would be lucky if he got half-a-crown out of him. Still, even half-a-crown was something in those early days of struggle.

Whilst the doctor had been running his eyes over the stranger, the latter had been plunging his hands into pocket after pocket of his heavy coat. The heat of the weather, his dress, and this exercise of pocket-rummaging had all combined to still further redden his face, which had changed from brick to beet, with a gloss of moisture on his brow. This extreme ruddiness brought a clue at last to the observant doctor. Surely it was not to be attained without alcohol. In alcohol lay the secret of this man’s trouble. Some little delicacy was needed, however, in showing him that he had read his case aright—that at a glance he had penetrated to the inmost sources of his ailments.

“It’s very hot,” observed the stranger, mopping his forehead.

“Yes, it is weather which tempts one to drink rather more beer than is good for one,” answered Dr. Horace Wilkinson, looking very knowingly at his companion from over his finger-tips.

“Dear, dear, you shouldn’t do that.”

“I! I never touch beer.”

“Neither do I. I’ve been an abstainer for twenty years.”

This was depressing. Dr. Wilkinson blushed until he was nearly as red as the other. “May I ask what I can do for you?” he asked, picking up his stethoscope and tapping it gently against his thumb-nail.

“Yes, I was just going to tell you. I heard of your coming, but I couldn’t get round before——” He broke into a nervous little cough.

“Yes?” said the doctor encouragingly.

“I should have been here three weeks ago, but you know how these things get put off.” He coughed again behind his large red hand.

“I do not think that you need say anything more,” said the doctor, taking over the case with an easy air of command. “Your cough is quite sufficient. It is entirely bronchial by the sound. No doubt the mischief is circumscribed at present, but there is always the danger that it may spread, so you have done wisely to come to me. A little judicious treatment will soon set you right. Your waistcoat, please, but not your shirt. Puff out your chest and say ninety-nine in a deep voice.”

The red-faced man began to laugh. “It’s all right, doctor,” said he. “That cough comes from chewing tobacco, and I know it’s a very bad habit. Nine-and-ninepence is what I have to say to you, for I’m the officer of the gas company, and they have a claim against you for that on the metre.”

Dr. Horace Wilkinson collapsed into his chair. “Then you’re not a patient?” he gasped.

“Never needed a doctor in my life, sir.”

“Oh, that’s all right.” The doctor concealed his disappointment under an affectation of facetiousness. “You don’t look as if you troubled them much. I don’t know what we should do if every one were as robust. I shall call at the company’s offices and pay this small amount.”

“If you could make it convenient, sir, now that I am here, it would save trouble——”

“Oh, certainly!” These eternal little sordid money troubles were more trying to the doctor than plain living or scanty food. He took out his purse and slid the contents on to the table. There were two half-crowns and some pennies. In his drawer he had ten golden sovereigns. But those were his rent. If he once broke in upon them he was lost. He would starve first.

“Dear me!” said he, with a smile, as at some strange, unheard-of incident. “I have run short of small change. I am afraid I shall have to call upon the company, after all.”

“Very well, sir.” The inspector rose, and with a practised glance around, which valued every article in the room, from the two-guinea carpet to the eight-shilling muslin curtains, he took his departure.

When he had gone Dr. Wilkinson rearranged his room, as was his habit a dozen times in the day. He laid out his large Quain’s Dictionary of Medicine in the forefront of the table so as to impress the casual patient that he had ever the best authorities at his elbow. Then he cleared all the little instruments out of his pocket-case—the scissors, the forceps, the bistouries, the lancets—and he laid them all out beside the stethoscope, to make as good a show as possible. His ledger, day-book, and visiting-book were spread in front of him. There was no entry in any of them yet, but it would not look well to have the covers too glossy and new, so he rubbed them together and daubed ink over them. Neither would it be well that any patient should observe that his name was the first in the book, so he filled up the first page of each with notes of imaginary visits paid to nameless patients during the last three weeks. Having done all this, he rested his head upon his hands and relapsed into the terrible occupation of waiting.

Terrible enough at any time to the young professional man, but most of all to one who knows that the weeks, and even the days during which he can hold out are numbered. Economise as he would, the money would still slip away in the countless little claims which a man never understands until he lives under a rooftree of his own. Dr. Wilkinson could not deny, as he sat at his desk and looked at the little heap of silver and coppers, that his chances of being a successful practitioner in Sutton were rapidly vanishing away.

And yet it was a bustling, prosperous town, with so much money in it that it seemed strange that a man with a trained brain and dexterous fingers should be starved out of it for want of employment. At his desk, Dr. Horace Wilkinson could see the never-ending double current of people which ebbed and flowed in front of his window. It was a busy street, and the air was forever filled with the dull roar of life, the grinding of the wheels, and the patter of countless feet. Men, women, and children, thousands and thousands of them passed in the day, and yet each was hurrying on upon his own business, scarce glancing at the small brass plate, or wasting a thought upon the man who waited in the front room. And yet how many of them would obviously, glaringly have been the better for his professional assistance. Dyspeptic men, anemic women, blotched faces, bilious complexions—they flowed past him, they needing him, he needing them, and yet the remorseless bar of professional etiquette kept them forever apart. What could he do? Could he stand at his own front door, pluck the casual stranger by the sleeve, and whisper in his ear, “Sir, you will forgive me for remarking that you are suffering from a severe attack of acne rosacea, which makes you a peculiarly unpleasant object. Allow me to suggest that a small prescription containing arsenic, which will not cost you more than you often spend upon a single meal, will be very much to your advantage.” Such an address would be a degradation to the high and lofty profession of Medicine, and there are no such sticklers for the ethics of that profession as some to whom she has been but a bitter and a grudging mother.

Dr. Horace Wilkinson was still looking moodily out of the window, when there came a sharp clang at the bell. Often it had rung, and with every ring his hopes had sprung up, only to dwindle away again, and change to leaden disappointment, as he faced some beggar or touting tradesman. But the doctor’s spirit was young and elastic, and again, in spite of all experience, it responded to that exhilarating summons. He sprang to his feet, cast his eyes over the table, thrust out his medical books a little more prominently, and hurried to the door. A groan escaped him as he entered the hall. He could see through the half-glazed upper panels that a gypsy van, hung round with wicker tables and chairs, had halted before his door, and that a couple of the vagrants, with a baby, were waiting outside. He had learned by experience that it was better not even to parley with such people.

“I have nothing for you,” said he, loosing the latch by an inch. “Go away!”

He closed the door, but the bell clanged once more. “Get away! Get away!” he cried impatiently, and walked back into his consulting-room. He had hardly seated himself when the bell went for the third time. In a towering passion he rushed back, flung open the door.

“What the——?”

“If you please, sir, we need a doctor.”

In an instant he was rubbing his hands again with his blandest professional smile. These were patients, then, whom he had tried to hunt from his doorstep—the very first patients, whom he had waited for so impatiently. They did not look very promising. The man, a tall, lank-haired gypsy, had gone back to the horse’s head. There remained a small, hard-faced woman with a great bruise all round her eye. She wore a yellow silk handkerchief round her head, and a baby, tucked in a red shawl, was pressed to her bosom.

“Pray step in, madam,” said Dr. Horace Wilkinson, with his very best sympathetic manner. In this case, at least, there could be no mistake as to diagnosis. “If you will sit on this sofa, I shall very soon make you feel much more comfortable.”

He poured a little water from his carafe into a saucer, made a compress of lint, fastened it over the injured eye, and secured the whole with a spica bandage, secundum artem.

“Thank ye kindly, sir,” said the woman, when his work was finished; “that’s nice and warm, and may God bless your honour. But it wasn’t about my eye at all that I came to see a doctor.”

“Not your eye?” Dr. Horace Wilkinson was beginning to be a little doubtful as to the advantages of quick diagnosis. It is an excellent thing to be able to surprise a patient, but hitherto it was always the patient who had surprised him.

“The baby’s got the measles.”

The mother parted the red shawl, and exhibited a little dark, black-eyed gypsy baby, whose swarthy face was all flushed and mottled with a dark-red rash. The child breathed with a rattling sound, and it looked up at the doctor with eyes which were heavy with want of sleep and crusted together at the lids.

“Hum! Yes. Measles, sure enough—and a smart attack.”

“I just wanted you to see her, sir, so that you could signify.”

“Could what?”

“Signify, if anything happened.”

“Oh, I see—certify.”

“And now that you’ve seen it, sir, I’ll go on, for Reuben—that’s my man—is in a hurry.”

“But don’t you want any medicine?”

“Oh, now you’ve seen it, it’s all right. I’ll let you know if anything happens.”

“But you must have some medicine. The child is very ill.” He descended into the little room which he had fitted as a surgery, and he made up a two-ounce bottle of cooling medicine. In such cities as Sutton there are few patients who can afford to pay a fee to both doctor and chemist, so that unless the physician is prepared to play the part of both he will have little chance of making a living at either.

“There is your medicine, madam. You will find the directions upon the bottle. Keep the child warm and give it a light diet.”

“Thank you kindly, sir.” She shouldered her baby and marched for the door.

“Excuse me, madam,” said the doctor nervously. “Don’t you think it too small a matter to make a bill of? Perhaps it would be better if we had a settlement at once.”

The gypsy woman looked at him reproachfully out of her one uncovered eye.

“Are you going to charge me for that?” she asked. “How much, then?”

“Well, say half-a-crown.” He mentioned the sum in a half-jesting way, as though it were too small to take serious notice of, but the gypsy woman raised quite a scream at the mention of it.

“‘Arf-a-crown! for that?”

“Well, my good woman, why not go to the poor doctor if you cannot afford a fee?”

She fumbled in her pocket, craning awkwardly to keep her grip upon the baby.

“Here’s sevenpence,” she said at last, holding out a little pile of copper coins. “I’ll give you that and a wicker footstool.”

“But my fee is half-a-crown.” The doctor’s views of the glory of his profession cried out against this wretched haggling, and yet what was he to do? “Where am I to get ‘arf-a-crown? It is well for gentlefolk like you who sit in your grand houses, and can eat and drink what you like, an’ charge ‘arf-a-crown for just saying as much as, ”Ow d’ye do?’ We can’t pick up’ arf-crowns like that. What we gets we earns ‘ard. This sevenpence is just all I’ve got. You told me to feed the child light. She must feed light, for what she’s to have is more than I know.”

Whilst the woman had been speaking, Dr. Horace Wilkinson’s eyes had wandered to the tiny heap of money upon the table, which represented all that separated him from absolute starvation, and he chuckled to himself at the grim joke that he should appear to this poor woman to be a being living in the lap of luxury. Then he picked up the odd coppers, leaving only the two half-crowns upon the table.

“Here you are,” he said brusquely. “Never mind the fee, and take these coppers. They may be of some use to you. Good-bye!” He bowed her out, and closed the door behind her. After all she was the thin edge of the wedge. These wandering people have great powers of recommendation. All large practices have been built up from such foundations. The hangers-on to the kitchen recommend to the kitchen, they to the drawing-room, and so it spreads. At least he could say now that he had had a patient.

He went into the back room and lit the spirit-kettle to boil the water for his tea, laughing the while at the recollection of his recent interview. If all patients were like this one it could easily be reckoned how many it would take to ruin him completely. Putting aside the dirt upon his carpet and the loss of time, there were twopence gone upon the bandage, fourpence or more upon the medicine, to say nothing of phial, cork, label, and paper. Then he had given her fivepence, so that his first patient had absorbed altogether not less than one sixth of his available capital. If five more were to come he would be a broken man. He sat down upon the portmanteau and shook with laughter at the thought, while he measured out his one spoonful and a half of tea at one shilling eightpence into the brown earthenware teapot. Suddenly, however, the laugh faded from his face, and he cocked his ear towards the door, standing listening with a slanting head and a sidelong eye. There had been a rasping of wheels against the curb, the sound of steps outside, and then a loud peal at the bell. With his teaspoon in his hand he peeped round the corner and saw with amazement that a carriage and pair were waiting outside, and that a powdered footman was standing at the door. The spoon tinkled down upon the floor, and he stood gazing in bewilderment. Then, pulling himself together, he threw open the door.

“Young man,” said the flunky, “tell your master, Dr. Wilkinson, that he is wanted just as quick as ever he can come to Lady Millbank, at the Towers. He is to come this very instant. We’d take him with us, but we have to go back to see if Dr. Mason is home yet. Just you stir your stumps and give him the message.”

The footman nodded and was off in an instant, while the coachman lashed his horses and the carriage flew down the street.

Here was a new development. Dr. Horace Wilkinson stood at his door and tried to think it all out. Lady Millbank, of the Towers! People of wealth and position, no doubt. And a serious case, or why this haste and summoning of two doctors? But, then, why in the name of all that is wonderful should he be sent for?

He was obscure, unknown, without influence. There must be some mistake. Yes, that must be the true explanation; or was it possible that some one was attempting a cruel hoax upon him? At any rate, it was too positive a message to be disregarded. He must set off at once and settle the matter one way or the other.

But he had one source of information. At the corner of the street was a small shop where one of the oldest inhabitants dispensed newspapers and gossip. He could get information there if anywhere. He put on his well-brushed top hat, secreted instruments and bandages in all his pockets, and without waiting for his tea closed up his establishment and started off upon his adventure.

The stationer at the corner was a human directory to every one and everything in Sutton, so that he soon had all the information which he wanted. Sir John Millbank was very well known in the town, it seemed. He was a merchant prince, an exporter of pens, three times mayor, and reported to be fully worth two millions sterling.

The Towers was his palatial seat, just outside the city. His wife had been an invalid for some years, and was growing worse. So far the whole thing seemed to be genuine enough. By some amazing chance these people really had sent for him.

And then another doubt assailed him, and he turned back into the shop.

“I am your neighbour, Dr. Horace Wilkinson,” said he. “Is there any other medical man of that name in the town?”

No, the stationer was quite positive that there was not.

That was final, then. A great good fortune had come in his way, and he must take prompt advantage of it. He called a cab and drove furiously to the Towers, with his brain in a whirl, giddy with hope and delight at one moment, and sickened with fears and doubts at the next lest the case should in some way be beyond his powers, or lest he should find at some critical moment that he was without the instrument or appliance that was needed. Every strange and outre case of which he had ever heard or read came back into his mind, and long before he reached the Towers he had worked himself into a positive conviction that he would be instantly required to do a trephining at the least.

The Towers was a very large house, standing back amid trees, at the head of a winding drive. As he drove up the doctor sprang out, paid away half his worldly assets as a fare, and followed a stately footman who, having taken his name, led him through the oak-panelled, stained-glass hall, gorgeous with deers’ heads and ancient armour, and ushered him into a large sitting-room beyond. A very irritable-looking, acid-faced man was seated in an armchair by the fireplace, while two young ladies in white were standing together in the bow window at the further end.

“Hullo! hullo! hullo! What’s this—heh?” cried the irritable man. “Are you Dr. Wilkinson? Eh?”

“Yes, sir, I am Dr. Wilkinson.”

“Really, now. You seem very young—much younger than I expected. Well, well, well, Mason’s old, and yet he don’t seem to know much about it. I suppose we must try the other end now. You’re the Wilkinson who wrote something about the lungs? Heh?”

Here was a light! The only two letters which the doctor had ever written to The Lancet—modest little letters thrust away in a back column among the wrangles about medical ethics and the inquiries as to how much it took to keep a horse in the country—had been upon pulmonary disease. They had not been wasted, then. Some eye had picked them out and marked the name of the writer. Who could say that work was ever wasted, or that merit did not promptly meet with its reward?

“Yes, I have written on the subject.”

“Ha! Well, then, where’s Mason?”

“I have not the pleasure of his acquaintance.”

“No?—that’s queer too. He knows you and thinks a lot of your opinion. You’re a stranger in the town, are you not?”

“Yes, I have only been here a very short time.”

“That was what Mason said. He didn’t give me the address. Said he would call on you and bring you, but when the wife got worse of course I inquired for you and sent for you direct. I sent for Mason, too, but he was out. However, we can’t wait for him, so just run away upstairs and do what you can.”

“Well, I am placed in a rather delicate position,” said Dr. Horace Wilkinson, with some hesitation. “I am here, as I understand, to meet my colleague, Dr. Mason, in consultation. It would, perhaps, hardly be correct for me to see the patient in his absence. I think that I would rather wait.”

“Would you, by Jove! Do you think I’ll let my wife get worse while the doctor is coolly kicking his heels in the room below? No, sir, I am a plain man, and I tell you that you will either go up or go out.”

The style of speech jarred upon the doctor’s sense of the fitness of things, but still when a man’s wife is ill much may be overlooked. He contented himself by bowing somewhat stiffly. “I shall go up, if you insist upon it,” said he.

“I do insist upon it. And another thing, I won’t have her thumped about all over the chest, or any hocus-pocus of the sort. She has bronchitis and asthma, and that’s all. If you can cure it well and good. But it only weakens her to have you tapping and listening, and it does no good either.”

Personal disrespect was a thing that the doctor could stand; but the profession was to him a holy thing, and a flippant word about it cut him to the quick.

“Thank you,” said he, picking up his hat. “I have the honour to wish you a very good day. I do not care to undertake the responsibility of this case.”

“Hullo! what’s the matter now?”

“It is not my habit to give opinions without examining my patient. I wonder that you should suggest such a course to a medical man. I wish you good day.”

But Sir John Millbank was a commercial man, and believed in the commercial principle that the more difficult a thing is to attain the more valuable it is. A doctor’s opinion had been to him a mere matter of guineas. But here was a young man who seemed to care nothing either for his wealth or title. His respect for his judgment increased amazingly.

“Tut! tut!” said he; “Mason is not so thin-skinned. There! there! Have your way! Do what you like and I won’t say another word. I’ll just run upstairs and tell Lady Millbank that you are coming.”

The door had hardly closed behind him when the two demure young ladies darted out of their corner, and fluttered with joy in front of the astonished doctor.

“Oh, well done! well done!” cried the taller, clapping her hands.

“Don’t let him bully you, doctor,” said the other. “Oh, it was so nice to hear you stand up to him. That’s the way he does with poor Dr. Mason. Dr. Mason has never examined mamma yet. He always takes papa’s word for everything. Hush, Maude; here he comes again.” They subsided in an instant into their corner as silent and demure as ever.

Dr. Horace Wilkinson followed Sir John up the broad, thick-carpeted staircase, and into the darkened sick room. In a quarter of an hour he had sounded and sifted the case to the uttermost, and descended with the husband once more to the drawing-room. In front of the fireplace were standing two gentlemen, the one a very typical, clean-shaven, general practitioner, the other a striking-looking man of middle age, with pale blue eyes and a long red beard.

“Hullo, Mason, you’ve come at last!”

“Yes, Sir John, and I have brought, as I promised, Dr. Wilkinson with me.”

“Dr. Wilkinson! Why, this is he.”

Dr. Mason stared in astonishment. “I have never seen the gentleman before!” he cried.

“Nevertheless I am Dr. Wilkinson—Dr. Horace Wilkinson, of 114 Canal View.”

“Good gracious, Sir John!” cried Dr. Mason.

“Did you think that in a case of such importance I should call in a junior local practitioner! This is Dr. Adam Wilkinson, lecturer on pulmonary diseases at Regent’s College, London, physician upon the staff of the St. Swithin’s Hospital, and author of a dozen works upon the subject. He happened to be in Sutton upon a visit, and I thought I would utilise his presence to have a first-rate opinion upon Lady Millbank.”

“Thank you,” said Sir John, dryly. “But I fear my wife is rather tired now, for she has just been very thoroughly examined by this young gentleman. I think we will let it stop at that for the present; though, of course, as you have had the trouble of coming here, I should be glad to have a note of your fees.”

When Dr. Mason had departed, looking very disgusted, and his friend, the specialist, very amused, Sir John listened to all the young physician had to say about the case.

“Now, I’ll tell you what,” said he, when he had finished. “I’m a man of my word, d’ye see? When I like a man I freeze to him. I’m a good friend and a bad enemy. I believe in you, and I don’t believe in Mason. From now on you are my doctor, and that of my family. Come and see my wife every day. How does that suit your book?”

“I am extremely grateful to you for your kind intentions toward me, but I am afraid there is no possible way in which I can avail myself of them.”

“Heh! what d’ye mean?”

“I could not possibly take Dr. Mason’s place in the middle of a case like this. It would be a most unprofessional act.”

“Oh, well, go your own way!” cried Sir John, in despair. “Never was such a man for making difficulties. You’ve had a fair offer and you’ve refused it, and now you can just go your own way.”

The millionaire stumped out of the room in a huff, and Dr. Horace Wilkinson made his way homeward to his spirit-lamp and his one-and-eightpenny tea, with his first guinea in his pocket, and with a feeling that he had upheld the best traditions of his profession.

And yet this false start of his was a true start also, for it soon came to Dr. Mason’s ears that his junior had had it in his power to carry off his best patient and had forborne to do so. To the honour of the profession be it said that such forbearance is the rule rather than the exception, and yet in this case, with so very junior a practitioner and so very wealthy a patient, the temptation was greater than is usual. There was a grateful note, a visit, a friendship, and now the well-known firm of Mason and Wilkinson is doing the largest family practice in Sutton.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

A False Start (#05)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

A Suburban Fairy Tale

A Suburban Fairy Tale

by Katherine Mansfield

Mr. and Mrs. B. sat at breakfast in the cosy red dining-room of their “snug little crib just under half-an-hour’s run from the City.”

There was a good fire in the grate—for the dining-room was the living-room as well—the two windows overlooking the cold empty garden patch were closed, and the air smelled agreeably of bacon and eggs, toast and coffee. Now that this rationing business was really over Mr. B. made a point of a thoroughly good tuck-in before facing the very real perils of the day. He didn’t mind who knew it—he was a true Englishman about his breakfast—he had to have it; he’d cave in without it, and if you told him that these Continental chaps could get through half the morning’s work he did on a roll and a cup of coffee—you simply didn’t know what you were talking about.

Mr. B. was a stout youngish man who hadn’t been able—worse luck—to chuck his job and join the Army; he’d tried for four years to get another chap to take his place but it was no go. He sat at the head of the table reading the Daily Mail. Mrs. B. was a youngish plump little body, rather like a pigeon. She sat opposite, preening herself behind the coffee set and keeping an eye of warning love on little B. who perched between them, swathed in a napkin and tapping the top of a soft-boiled egg.

Alas! Little B. was not at all the child that such parents had every right to expect. He was no fat little trot, no dumpling, no firm little pudding. He was under-sized for his age, with legs like macaroni, tiny claws, soft, soft hair that felt like mouse fur, and big wide-open eyes. For some strange reason everything in life seemed the wrong size for Little B.—too big and too violent. Everything knocked him over, took the wind out of his feeble sails and left him gasping and frightened. Mr. and Mrs. B. were quite powerless to prevent this; they could only pick him up after the mischief was done—and try to set him going again. And Mrs. B. loved him as only weak children are loved—and when Mr. B. thought what a marvellous little chap he was too—thought of the spunk of the little man, he—well he—by George—he …

“Why aren’t there two kinds of eggs?” said Little B. “Why aren’t there little eggs for children and big eggs like what this one is for grown-ups?”

“Scotch hares,” said Mr. B. “Fine Scotch hares for 5s. 3d. How about getting one, old girl?”

“It would be a nice change, wouldn’t it?” said Mrs. B. “Jugged.”

And they looked across at each other and there floated between them the Scotch hare in its rich gravy with stuffing balls and a white pot of red-currant jelly accompanying it.

“We might have had it for the week-end,” said Mrs. B. “But the butcher has promised me a nice little sirloin and it seems a pity”… Yes, it did and yet … Dear me, it was very difficult to decide. The hare would have been such a change—on the other hand, could you beat a really nice little sirloin?

“There’s hare soup, too,” said Mr. B. drumming his fingers on the table. “Best soup in the world!”

“O-Oh!” cried Little B. so suddenly and sharply that it gave them quite a start—“Look at the whole lot of sparrows flown on to our lawn”—he waved his spoon. “Look at them,” he cried. “Look!” And while he spoke, even though the windows were closed, they heard a loud shrill cheeping and chirping from the garden.

“Get on with your breakfast like a good boy, do,” said his mother, and his father said, “You stick to the egg, old man, and look sharp about it.”

“But look at them—look at them all hopping,” he cried. “They don’t keep still not for a minute. Do you think they’re hungry, father?”

Cheek-a-cheep-cheep-cheek! cried the sparrows.

“Best postpone it perhaps till next week,” said Mr. B., “and trust to luck they’re still to be had then.”

“Yes, perhaps that would be wiser,” said Mrs. B.

Mr. B. picked another plum out of his paper.

“Have you bought any of those controlled dates yet?”

“I managed to get two pounds yesterday,” said Mrs. B.

“Well a date pudding’s a good thing,” said Mr. B. And they looked across at each other and there floated between them a dark round pudding covered with creamy sauce. “It would be a nice change, wouldn’t it?” said Mrs. B.

Outside on the grey frozen grass the funny eager sparrows hopped and fluttered. They were never for a moment still. They cried, flapped their ungainly wings. Little B., his egg finished, got down, took his bread and marmalade to eat at the window.

“Do let us give them some crumbs,” he said. “Do open the window, father, and throw them something. Father, please!”

“Oh, don’t nag, child,” said Mrs. B., and his father said—“Can’t go opening windows, old man. You’d get your head bitten off.”

“But they’re hungry,” cried Little B., and the sparrows’ little voices were like ringing of little knives being sharpened. Cheek-a-cheep-cheep-cheek! they cried.

Little B. dropped his bread and marmalade inside the china flower pot in front of the window. He slipped behind the thick curtains to see better, and Mr. and Mrs. B. went on reading about what you could get now without coupons—no more ration books after May—a glut of cheese—a glut of it—whole cheeses revolved in the air between them like celestial bodies.

Suddenly as Little B. watched the sparrows on the grey frozen grass, they grew, they changed, still flapping and squeaking. They turned into tiny little boys, in brown coats, dancing, jigging outside, up and down outside the window squeaking, “Want something to eat, want something to eat!” Little B. held with both hands to the curtain. “Father,” he whispered, “Father! They’re not sparrows. They’re little boys. Listen, Father!” But Mr. and Mrs. B. would not hear. He tried again. “Mother,” he whispered. “Look at the little boys. They’re not sparrows, Mother!” But nobody noticed his nonsense.

“All this talk about famine,” cried Mr. B., “all a Fake, all a Blind.”

With white shining faces, their arms flapping in the big coats, the little boys danced. “Want something to eat—want something to eat.”

“Father,” muttered Little B. “Listen, Father! Mother, listen, please!”

“Really!” said Mrs. B. “The noise those birds are making! I’ve never heard such a thing.”

“Fetch me my shoes, old man,” said Mr. B.

Cheek-a-cheep-cheep-cheek! said the sparrows.

Now where had that child got to? “Come and finish your nice cocoa, my pet,” said Mrs. B.

Mr. B. lifted the heavy cloth and whispered, “Come on, Rover,” but no little dog was there.

“He’s behind the curtain,” said Mrs. B.

“He never went out of the room,” said Mr. B.

Mrs. B. went over to the window, and Mr. B. followed. And they looked out. There on the grey frozen grass, with a white white face, the little boy’s thin arms flapping like wings, in front of them all, the smallest, tiniest was Little B. Mr. and Mrs. B. heard his voice above all the voices, “Want something to eat, want something to eat.”

Somehow, somehow, they opened the window. “You shall! All of you. Come in at once. Old man! Little man!”

But it was too late. The little boys were changed into sparrows again, and away they flew—out of sight—out of call.

A Suburban Fairy Tale (1917)

by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923)

From: Something Childish and Other Stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Katherine Mansfield, Mansfield, Katherine

The Head-Hunter

The Head-Hunter

by O. Henry

When the war between Spain and George Dewey was over, I went to the Philippine Islands. There I remained as bush-whacker correspondent for my paper until its managing editor notified me that an eight-hundred-word cablegram describing the grief of a pet carabao over the death of an infant Moro was not considered by the office to be war news. So I resigned, and came home.

On board the trading-vessel that brought me back I pondered much upon the strange things I had sensed in the weird archipelago of the yellow-brown people. The manœuvres and skirmishings of the petty war interested me not: I was spell-bound by the outlandish and unreadable countenance of that race that had turned its expressionless gaze upon us out of an unguessable past.

Particularly during my stay in Mindanao had I been fascinated and attracted by that delightfully original tribe of heathen known as the head-hunters. Those grim, flinty, relentless little men, never seen, but chilling the warmest noonday by the subtle terror of their concealed presence, paralleling the trail of their prey through unmapped forests, across perilous mountain-tops, adown bottomless chasms, into uninhabitable jungles, always near with the invisible hand of death uplifted, betraying their pursuit only by such signs as a beast or a bird or a gliding serpent might make—a twig crackling in the awful sweat- soaked night, a drench of dew showering from the screening foliage of a giant tree, a whisper at even from the rushes of a water-level—a hint of death for every mile and every hour—they amused me greatly, those little fellows of one idea.

When you think of it, their method is beautifully and almost hilariously effective and simple.

You have your hut in which you live and carry out the destiny that was decreed for you. Spiked to the jamb of your bamboo doorway is a basket made of green withies, plaited. From time to time as vanity or ennui or love or jealousy or ambition may move you, you creep forth with your snickersnee and take up the silent trail. Back from it you come, triumphant, bearing the severed, gory head of your victim, which you deposit with pardonable pride in the basket at the side of your door. It may be the head of your enemy, your friend, or a stranger, according as competition, jealousy, or simple sportiveness has been your incentive to labour.

In any case, your reward is certain. The village men, in passing, stop to congratulate you, as your neighbour on weaker planes of life stops to admire and praise the begonias in your front yard. Your particular brown maid lingers, with fluttering bosom, casting soft tiger’s eyes at the evidence of your love for her. You chew betel-nut and listen, content, to the intermittent soft drip from the ends of the severed neck arteries. And you show your teeth and grunt like a water-buffalo—which is as near as you can come to laughing—at the thought that the cold, acephalous body of your door ornament is being spotted by wheeling vultures in the Mindanaoan wilds.

Truly, the life of the merry head-hunter captivated me. He had reduced art and philosophy to a simple code. To take your adversary’s head, to basket it at the portal of your castle, to see it lying there, a dead thing, with its cunning and stratagems and power gone—Is there a better way to foil his plots, to refute his arguments, to establish your superiority over his skill and wisdom?

The ship that brought me home was captained by an erratic Swede, who changed his course and deposited me, with genuine compassion, in a small town on the Pacific coast of one of the Central American republics, a few hundred miles south of the port to which he had engaged to convey me. But I was wearied of movement and exotic fancies; so I leaped contentedly upon the firm sands of the village of Mojada, telling myself I should be sure to find there the rest that I craved. After all, far better to linger there (I thought), lulled by the sedative plash of the waves and the rustling of palm-fronds, than to sit upon the horsehair sofa of my parental home in the East, and there, cast down by currant wine and cake, and scourged by fatuous relatives, drivel into the ears of gaping neighbours sad stories of the death of colonial governors.

When I first saw Chloe Greene she was standing, all in white, in the doorway of her father’s tile-roofed dobe house. She was polishing a silver cup with a cloth, and she looked like a pearl laid against black

O. Henry

(1862 – 1910)

The Head-Hunter

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Henry, O.

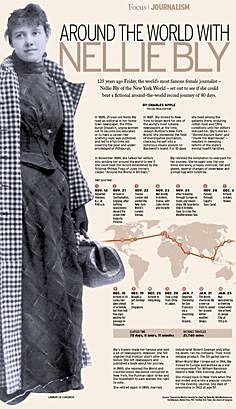

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter III: In the temporary home)

by Nellie Bly

I was left to begin my career as Nellie Brown, the insane girl. As I walked down the avenue I tried to assume the look which maidens wear in pictures entitled “Dreaming.” “Far-away” expressions have a crazy air. I passed through the little paved yard to the entrance of the Home. I pulled the bell, which sounded loud enough for a church chime, and nervously awaited the opening of the door to the Home, which I intended should ere long cast me forth and out upon the charity of the police. The door was thrown back with a vengeance, and a short, yellow-haired girl of some thirteen summers stood before me.

“Is the matron in?” I asked, faintly.

“Yes, she’s in; she’s busy. Go to the back parlor,” answered the girl, in a loud voice, without one change in her peculiarly matured face.

At the temporary home for women.

I followed these not overkind or polite instructions and found myself in a dark, uncomfortable back-parlor. There I awaited the arrival of my hostess. I had been seated some twenty minutes at the least, when a slender woman, clad in a plain, dark dress entered and, stopping before me, ejaculated inquiringly, “Well?”

“Are you the matron?” I asked.

“No,” she replied, “the matron is sick; I am her assistant. What do you want?”

“I want to stay here for a few days, if you can accommodate me.”

“Well, I have no single rooms, we are so crowded; but if you will occupy a room with another girl, I shall do that much for you.”

“I shall be glad of that,” I answered. “How much do you charge?” I had brought only about seventy cents along with me, knowing full well that the sooner my funds were exhausted the sooner I should be put out, and to be put out was what I was working for.

“We charge thirty cents a night,” was her reply to my question, and with that I paid her for one night’s lodging, and she left me on the plea of having something else to look after. Left to amuse myself as best I could, I took a survey of my surroundings.

They were not cheerful, to say the least. A wardrobe, desk, book-case, organ, and several chairs completed the furnishment of the room, into which the daylight barely came.

By the time I had become familiar with my quarters a bell, which rivaled the door-bell in its loudness, began clanging in the basement, and simultaneously

women went trooping down-stairs from all parts of the house. I imagined, from the obvious signs, that dinner was served, but as no one had said anything to me I made no effort to follow in the hungry train. Yet I did wish that some one would invite me down. It always produces such a lonely, homesick feeling to know others are eating, and we haven’t a chance, even if we are not hungry. I was glad when the assistant matron came up and asked me if I did not want something to eat. I replied that I did, and then I asked her what her name was. Mrs. Stanard, she said, and I immediately wrote it down in a notebook I had taken with me for the purpose of making memoranda, and in which I had written several pages of utter nonsense for inquisitive scientists.

Thus equipped I awaited developments. But my dinner–well, I followed Mrs. Stanard down the uncarpeted stairs into the basement; where a large number of women were eating. She found room for me at a table with three other women. The short-haired slavey who had opened the door now put in an appearance as waiter. Placing her arms akimbo and staring me out of countenance she said:

“Boiled mutton, boiled beef, beans, potatoes, coffee or tea?”

“Beef, potatoes, coffee and bread,” I responded.

“Bread goes in,” she explained, as she made her way to the kitchen, which was in the rear. It was not very long before she returned with what I had ordered on a large, badly battered tray, which she banged down before me. I began my simple meal. It was not very enticing, so while making a feint of eating I watched the others.

I have often moralized on the repulsive form charity always assumes! Here was a home for deserving women and yet what a mockery the name was. The floor was bare, and the little wooden tables were sublimely ignorant of such modern beautifiers as varnish, polish and table-covers. It is useless to talk about the cheapness of linen and its effect on civilization. Yet these honest workers, the most deserving of women, are asked to call this spot of bareness–home.

I have often moralized on the repulsive form charity always assumes! Here was a home for deserving women and yet what a mockery the name was. The floor was bare, and the little wooden tables were sublimely ignorant of such modern beautifiers as varnish, polish and table-covers. It is useless to talk about the cheapness of linen and its effect on civilization. Yet these honest workers, the most deserving of women, are asked to call this spot of bareness–home.

When the meal was finished each woman went to the desk in the corner, where Mrs. Stanard sat, and paid her bill. I was given a much-used, and abused, red check, by the original piece of humanity in shape of my waitress. My bill was about thirty cents.

After dinner I went up-stairs and resumed my former place in the back parlor. I was quite cold and uncomfortable, and had fully made up my mind that I could not endure that sort of business long, so the sooner I assumed my insane points the sooner I would be released from enforced idleness. Ah! that was indeed the longest day I had ever lived. I listlessly watched the women in the front parlor, where all sat except myself.

One did nothing but read and scratch her head and occasionally call out mildly, “Georgie,” without lifting her eyes from her book. “Georgie” was her over-frisky boy, who had more noise in him than any child I ever saw before. He did everything that was rude and unmannerly, I thought, and the mother never said a word unless she heard some one else yell at him. Another woman always kept going to sleep and waking herself up with her own snoring. I really felt wickedly thankful it was only herself she awakened. The majority of the women sat there doing nothing, but there were a few who made lace and knitted unceasingly. The enormous door-bell seemed to be going all the time, and so did the short-haired girl. The latter was, besides, one of those girls who sing all the time snatches of all the songs and hymns that have been composed for the last fifty years. There is such a thing as martyrdom in these days. The ringing of the bell brought more people who wanted shelter for the night. Excepting one woman, who was from the country on a day’s shopping expedition, they were working women, some of them with children.

As it drew toward evening Mrs. Stanard came to me and said:

“What is wrong with you? Have you some sorrow or trouble?”

“No,” I said, almost stunned at the suggestion. “Why?”

“Oh, because,” she said, womanlike, “I can see it in your face. It tells the story of a great trouble.”

“Yes, everything is so sad,” I said, in a haphazard way, which I had intended to reflect my craziness.

“But you must not allow that to worry you. We all have our troubles, but we get over them in good time. What kind of work are you trying to get?”

“I do not know; it’s all so sad,” I replied.

“Would you like to be a nurse for children and wear a nice white cap and apron?” she asked.

I put my handkerchief up to my face to hide a smile, and replied in a muffled tone, “I never worked; I don’t know how.”

“But you must learn,” she urged; “all these women here work.”

“Do they?” I said, in a low, thrilling whisper. “Why, they look horrible to me; just like crazy women. I am so afraid of them.”

“They don’t look very nice,” she answered, assentingly, “but they are good, honest working women. We do not keep crazy people here.”

I again used my handkerchief to hide a smile, as I thought that before morning she would at least think she had one crazy person among her flock.

“They all look crazy,” I asserted again, “and I am afraid of them. There are so many crazy people about, and one can never tell what they will do. Then there

are so many murders committed, and the police never catch the murderers,” and I finished with a sob that would have broken up an audience of blase critics. She gave a sudden and convulsive start, and I knew my first stroke had gone home. It was amusing to see what a remarkably short time it took her to get up from her chair and to whisper hurriedly: “I’ll come back to talk with you after a while.” I knew she would not come back and she did not.

When the supper-bell rang I went along with the others to the basement and partook of the evening meal, which was similar to dinner, except that there was

a smaller bill of fare and more people, the women who are employed outside during the day having returned. After the evening meal we all adjourned to the parlors, where all sat, or stood, as there were not chairs enough to go round.

It was a wretchedly lonely evening, and the light which fell from the solitary gas jet in the parlor, and oil-lamp the hall, helped to envelop us in a dusky

hue and dye our spirits navy blue. I felt it would not require many inundations of this atmosphere to make me a fit subject for the place I was striving to

reach.

I watched two women, who seemed of all the crowd to be the most sociable, and I selected them as the ones to work out my salvation, or, more properly speaking, my condemnation and conviction. Excusing myself and saying that I felt lonely, I asked if I might join their company. They graciously consented, so with my hat and gloves on, which no one had asked me to lay aside, I sat down and listened to the rather wearisome conversation, in which I took no part, merely keeping up my sad look, saying “Yes,” or “No,” or “I can’t say,” to their observations. Several times I told them I thought everybody in the house looked crazy, but they were slow to catch on to my very original remark. One said her name was Mrs. King and that she was a Southern woman. Then she said that I had a Southern accent. She asked me bluntly if I did not really come from the South. I said “Yes.” The other woman got to talking about the Boston boats and asked me if I knew at what time they left.

For a moment I forgot my role of assumed insanity, and told her the correct hour of departure. She then asked me what work I was going to do, or if I had ever done any. I replied that I thought it very sad that there were so many working people in the world. She said in reply that she had been unfortunate and had come to New York, where she had worked at correcting proofs on a medical dictionary for some time, but that her health had given way under the task, and that she was now going to Boston again. When the maid came to tell us to go to bed I remarked that I was afraid, and again ventured the assertion that all the women in the house seemed to be crazy. The nurse insisted on my going to bed. I asked if I could not sit on the stairs, but she said, decisively: “No; for every one in the house would think you were crazy.” Finally I allowed them to take me to a room.

Here I must introduce a new personage by name into my narrative. It is the woman who had been a proofreader, and was about to return to Boston. She was a Mrs. Caine, who was as courageous as she was good-hearted. She came into my room, and sat and talked with me a long time, taking down my hair with gentle ways. She tried to persuade me to undress and go to bed, but I stubbornly refused to do so. During this time a number of the inmates of the house had gathered around us. They expressed themselves in various ways. “Poor loon!” they said. “Why, she’s crazy enough!” “I am afraid to stay with such a crazy being in house.” “She will murder us all before morning.” One woman was for sending for a policeman to take me at once. They were all in a terrible and real state of fright.

No one wanted to be responsible for me, and the woman who was to occupy the room with me declared that she would not stay with that “crazy woman” for all the money of the Vanderbilts. It was then that Mrs. Caine said she would stay with me. I told her I would like to have her do so. So she was left with me. She didn’t undress, but lay down on the bed, watchful of my movements. She tried to induce me to lie down, but I was afraid to do this. I knew that if I once gave way I should fall asleep and dream as pleasantly and peacefully as a child. I should, to use a slang expression, be liable to “give myself dead away.” So I insisted on sitting on the side of the bed and staring blankly at vacancy. My poor companion was put into a wretched state of unhappiness. Every few moments she would rise up to look at me. She told me that my eyes shone terribly brightly and then began to question me, asking me where I had lived, how long I had been in New York, what I had been doing, and many things besides. To all her questionings I had but one response–I told her that I had forgotten everything, that ever since my headache had come on I could not remember.

Poor soul! How cruelly I tortured her, and what a kind heart she had! But how I tortured all of them! One of them dreamed of me–as a nightmare. After I had been in the room an hour or so, I was myself startled by hearing a woman screaming in the next room. I began to imagine that I was really in an insane asylum.

Mrs. Caine woke up, looked around, frightened, and listened. She then went out and into the next room, and I heard her asking another woman some questions. When she came back she told me that the woman had had a hideous nightmare. She had been dreaming of me. She had seen me, she said, rushing at her with a knife in my hand, with the intention of killing her. In trying to escape me she had fortunately been able to scream, and so to awaken herself and scare off her nightmare. Then Mrs. Caine got into bed again, considerably agitated, but very sleepy.

Mrs. Caine woke up, looked around, frightened, and listened. She then went out and into the next room, and I heard her asking another woman some questions. When she came back she told me that the woman had had a hideous nightmare. She had been dreaming of me. She had seen me, she said, rushing at her with a knife in my hand, with the intention of killing her. In trying to escape me she had fortunately been able to scream, and so to awaken herself and scare off her nightmare. Then Mrs. Caine got into bed again, considerably agitated, but very sleepy.

I was weary, too, but I had braced myself up to the work, and was determined to keep awake all night so as to carry on my work of impersonation to a successful end in the morning. I heard midnight. I had yet six hours to wait for daylight. The time passed with excruciating slowness. Minutes appeared hours. The noises in the house and on the avenue ceased.

Fearing that sleep would coax me into its grasp, I commenced to review my life. How strange it all seems! One incident, if never so trifling, is but a link more to chain us to our unchangeable fate. I began at the beginning, and lived again the story of my life. Old friends were recalled with a pleasurable thrill; old enmities, old heartaches, old joys were once again present. The turned-down pages of my life were turned up, and the past was present.

When it was completed, I turned my thoughts bravely to the future, wondering, first, what the next day would bring forth, then making plans for the carrying out of my project. I wondered if I should be able to pass over the river to the goal of my strange ambition, to become eventually an inmate of the halls inhabited by my mentally wrecked sisters. And then, once in, what would be my experience? And after? How to get out? Bah! I said, they will get me out.

That was the greatest night of my existence. For a few hours I stood face to face with “self!”

I looked out toward the window and hailed with joy the slight shimmer of dawn. The light grew strong and gray, but the silence was strikingly still. My

companion slept. I had still an hour or two to pass over. Fortunately I found some employment for my mental activity. Robert Bruce in his captivity had won confidence in the future, and passed his time as pleasantly as possible under the circumstances, by watching the celebrated spider building his web. I had less noble vermin to interest me. Yet I believe I made some valuable discoveries in natural history. I was about to drop off to sleep in spite of myself when I was suddenly startled to wakefulness. I thought I heard something crawl and fall down upon the counterpane with an almost inaudible thud.

I had the opportunity of studying these interesting animals very thoroughly. They had evidently come for breakfast, and were not a little disappointed to

find that their principal plat was not there. They scampered up and down the pillow, came together, seemed to hold interesting converse, and acted in every way as if they were puzzled by the absence of an appetizing breakfast. After one consultation of some length they finally disappeared, seeking victims elsewhere, and leaving me to pass the long minutes by giving my attention to cockroaches, whose size and agility were something of a surprise to me.

My room companion had been sound asleep for a long time, but she now woke up, and expressed surprise at seeing me still awake and apparently as lively as a cricket. She was as sympathetic as ever. She came to me and took my hands and tried her best to console me, and asked me if I did not want to go home. She kept me up-stairs until nearly everybody was out of the house, and then took me down to the basement for coffee and a bun. After that, partaken in silence, I went back to my room, where I sat down, moping. Mrs. Caine grew more and more anxious. “What is to be done?” she kept exclaiming. “Where are your friends?” “No,” I answered, “I have no friends, but I have some trunks. Where are they? I want them.” The good woman tried to pacify me, saying that they would be found in good time. She believed that I was insane.

Yet I forgive her. It is only after one is in trouble that one realizes how little sympathy and kindness there are in the world. The women in the Home who

were not afraid of me had wanted to have some amusement at my expense, and so they had bothered me with questions and remarks that had I been insane would have been cruel and inhumane. Only this one woman among the crowd, pretty and delicate Mrs. Caine, displayed true womanly feeling. She compelled the others to cease teasing me and took the bed of the woman who refused to sleep near me. She protested against the suggestion to leave me alone and to have me locked up for the night so that I could harm no one. She insisted on remaining with me in order to administer aid should I need it. She smoothed my hair and bathed my brow and talked as soothingly to me as a mother would do to an ailing child. By every means she tried to have me go to bed and rest, and when it drew toward morning she got up and wrapped a blanket around me for fear I might get cold; then she kissed me on the brow and whispered, compassionately:

“Poor child, poor child!”

How much I admired that little woman’s courage and kindness. How I longed to reassure her and whisper that I was not insane, and how I hoped that, if any poor girl should ever be so unfortunate as to be what I was pretending to be, she might meet with one who possessed the same spirit of human kindness possessed by Mrs. Ruth Caine.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter III: In the temporary home)

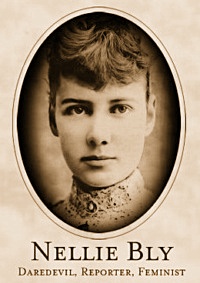

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

Sweet Ermengarde

Sweet Ermengarde

Or, The Heart of a Country Girl

By Percy Simple [H. P. Lovecraft]

Chapter I

A Simple Rustic Maid

Ermengarde Stubbs was the beauteous blonde daughter of Hiram Stubbs, a poor but honest farmer-bootlegger of Hogton, Vt. Her name was originally Ethyl Ermengarde, but her father persuaded her to drop the praenomen after the passage of the 18th Amendment, averring that it made him thirsty by reminding him of ethyl alcohol, C2H5OH. His own products contained mostly methyl or wood alcohol, CH3OH. Ermengarde confessed to sixteen summers, and branded as mendacious all reports to the effect that she was thirty. She had large black eyes, a prominent Roman nose, light hair which was never dark at the roots except when the local drug store was short on supplies, and a beautiful but inexpensive complexion. She was about 5ft 5.33…in tall, weighed 115.47 lbs. on her father’s copy scales—also off them—and was adjudged most lovely by all the village swains who admired her father’s farm and liked his liquid crops.

Ermengarde’s hand was sought in matrimony by two ardent lovers. ’Squire Hardman, who had a mortgage on the old home, was very rich and elderly. He was dark and cruelly handsome, and always rode horseback and carried a riding-crop. Long had he sought the radiant Ermengarde, and now his ardour was fanned to fever heat by a secret known to him alone—for upon the humble acres of Farmer Stubbs he had discovered a vein of rich GOLD!! “Aha!” said he, “I will win the maiden ere her parent knows of his unsuspected wealth, and join to my fortune a greater fortune still!” And so he began to call twice a week instead of once as before.

But alas for the sinister designs of a villain—’Squire Hardman was not the only suitor for the fair one. Close by the village dwelt another—the handsome Jack Manly, whose curly yellow hair had won the sweet Ermengarde’s affection when both were toddling youngsters at the village school. Jack had long been too bashful to declare his passion, but one day while strolling along a shady lane by the old mill with Ermengarde, he had found courage to utter that which was within his heart.

“O light of my life,” said he, “my soul is so overburdened that I must speak! Ermengarde, my ideal [he pronounced it i-deel!], life has become an empty thing without you. Beloved of my spirit, behold a suppliant kneeling in the dust before thee. Ermengarde—oh, Ermengarde, raise me to an heaven of joy and say that you will some day be mine! It is true that I am poor, but have I not youth and strength to fight my way to fame? This I can do only for you, dear Ethyl—pardon me, Ermengarde—my only, my most precious—” but here he paused to wipe his eyes and mop his brow, and the fair responded:

“Jack—my angel—at last—I mean, this is so unexpected and quite unprecedented! I had never dreamed that you entertained sentiments of affection in connexion with one so lowly as Farmer Stubbs’ child—for I am still but a child! Such is your natural nobility that I had feared—I mean thought—you would be blind to such slight charms as I possess, and that you would seek your fortune in the great city; there meeting and wedding one of those more comely damsels whose splendour we observe in fashion books.

“But, Jack, since it is really I whom you adore, let us waive all needless circumlocution. Jack—my darling—my heart has long been susceptible to your manly graces. I cherish an affection for thee—consider me thine own and be sure to buy the ring at Perkins’ hardware store where they have such nice imitation diamonds in the window.”

“Ermengarde, me love!”

“Jack—my precious!”

“My darling!”

“My own!”

“My Gawd!”

[Curtain]

Chapter II

And the Villain Still Pursued Her

But these tender passages, sacred though their fervour, did not pass unobserved by profane eyes; for crouched in the bushes and gritting his teeth was the dastardly ’Squire Hardman! When the lovers had finally strolled away he leapt out into the lane, viciously twirling his moustache and riding-crop, and kicking an unquestionably innocent cat who was also out strolling.

“Curses!” he cried—Hardman, not the cat—“I am foiled in my plot to get the farm and the girl! But Jack Manly shall never succeed! I am a man of power—and we shall see!”

Thereupon he repaired to the humble Stubbs’ cottage, where he found the fond father in the still-cellar washing bottles under the supervision of the gentle wife and mother, Hannah Stubbs. Coming directly to the point, the villain spoke:

“Farmer Stubbs, I cherish a tender affection of long standing for your lovely offspring, Ethyl Ermengarde. I am consumed with love, and wish her hand in matrimony. Always a man of few words, I will not descend to euphemism. Give me the girl or I will foreclose the mortgage and take the old home!”

“But, Sir,” pleaded the distracted Stubbs while his stricken spouse merely glowered, “I am sure the child’s affections are elsewhere placed.”

“She must be mine!” sternly snapped the sinister ’squire. “I will make her love me—none shall resist my will! Either she becomes muh wife or the old homestead goes!”

And with a sneer and flick of his riding-crop ’Squire Hardman strode out into the night.

Scarce had he departed, when there entered by the back door the radiant lovers, eager to tell the senior Stubbses of their new-found happiness. Imagine the universal consternation which reigned when all was known! Tears flowed like white ale, till suddenly Jack remembered he was the hero and raised his head, declaiming in appropriately virile accents:

“Never shall the fair Ermengarde be offered up to this beast as a sacrifice while I live! I shall protect her—she is mine, mine, mine—and then some! Fear not, dear father and mother to be—I will defend you all! You shall have the old home still [adverb, not noun—although Jack was by no means out of sympathy with Stubbs’ kind of farm produce] and I shall lead to the altar the beauteous Ermengarde, loveliest of her sex! To perdition with the crool ’squire and his ill-gotten gold—the right shall always win, and a hero is always in the right! I will go to the great city and there make a fortune to save you all ere the mortgage fall due! Farewell, my love—I leave you now in tears, but I shall return to pay off the mortgage and claim you as my bride!”

“Jack, my protector!”

“Ermie, my sweet roll!”

“Dearest!”

“Darling!—and don’t forget that ring at Perkins’.”

“Oh!”

“Ah!”

[Curtain]

Chapter III

A Dastardly Act

But the resourceful ’Squire Hardman was not so easily to be foiled. Close by the village lay a disreputable settlement of unkempt shacks, populated by a shiftless scum who lived by thieving and other odd jobs. Here the devilish villain secured two accomplices—ill-favoured fellows who were very clearly no gentlemen. And in the night the evil three broke into the Stubbs cottage and abducted the fair Ermengarde, taking her to a wretched hovel in the settlement and placing her under the charge of Mother Maria, a hideous old hag. Farmer Stubbs was quite distracted, and would have advertised in the papers if the cost had been less than a cent a word for each insertion. Ermengarde was firm, and never wavered in her refusal to wed the villain.

“Aha, my proud beauty,” quoth he, “I have ye in me power, and sooner or later I will break that will of thine! Meanwhile think of your poor old father and mother as turned out of hearth and home and wandering helpless through the meadows!”

“Oh, spare them, spare them!” said the maiden.

“Neverr . . . ha ha ha ha!” leered the brute.

And so the cruel days sped on, while all in ignorance young Jack Manly was seeking fame and fortune in the great city.

Chapter IV

Subtle Villainy

One day as ’Squire Hardman sat in the front parlour of his expensive and palatial home, indulging in his favourite pastime of gnashing his teeth and swishing his riding-crop, a great thought came to him; and he cursed aloud at the statue of Satan on the onyx mantelpiece.

“Fool that I am!” he cried. “Why did I ever waste all this trouble on the girl when I can get the farm by simply foreclosing? I never thought of that! I will let the girl go, take the farm, and be free to wed some fair city maid like the leading lady of that burlesque troupe which played last week at the Town Hall!”

And so he went down to the settlement, apologised to Ermengarde, let her go home, and went home himself to plot new crimes and invent new modes of villainy.

The days wore on, and the Stubbses grew very sad over the coming loss of their home and still but nobody seemed able to do anything about it. One day a party of hunters from the city chanced to stray over the old farm, and one of them found the gold!! Hiding his discovery from his companions, he feigned rattlesnake-bite and went to the Stubbs’ cottage for aid of the usual kind. Ermengarde opened the door and saw him. He also saw her, and in that moment resolved to win her and the gold. “For my old mother’s sake I must”—he cried loudly to himself. “No sacrifice is too great!”

Chapter V

The City Chap

Algernon Reginald Jones was a polished man of the world from the great city, and in his sophisticated hands our poor little Ermengarde was as a mere child. One could almost believe that sixteen-year-old stuff. Algy was a fast worker, but never crude. He could have taught Hardman a thing or two about finesse in sheiking. Thus only a week after his advent to the Stubbs family circle, where he lurked like the vile serpent that he was, he had persuaded the heroine to elope! It was in the night that she went leaving a note for her parents, sniffing the familiar mash for the last time, and kissing the cat goodbye—touching stuff! On the train Algernon became sleepy and slumped down in his seat, allowing a paper to fall out of his pocket by accident. Ermengarde, taking advantage of her supposed position as a bride-elect, picked up the folded sheet and read its perfumed expanse—when lo! she almost fainted! It was a love letter from another woman!!

“Perfidious deceiver!” she whispered at the sleeping Algernon, “so this is all that your boasted fidelity amounts to! I am done with you for all eternity!”

So saying, she pushed him out the window and settled down for a much needed rest.

Chapter VI

Alone in the Great City

When the noisy train pulled into the dark station at the city, poor helpless Ermengarde was all alone without the money to get back to Hogton. “Oh why,” she sighed in innocent regret, “didn’t I take his pocketbook before I pushed him out? Oh well, I should worry! He told me all about the city so I can easily earn enough to get home if not to pay off the mortgage!”

But alas for our little heroine—work is not easy for a greenhorn to secure, so for a week she was forced to sleep on park benches and obtain food from the bread-line. Once a wily and wicked person, perceiving her helplessness, offered her a position as dish-washer in a fashionable and depraved cabaret; but our heroine was true to her rustic ideals and refused to work in such a gilded and glittering palace of frivolity—especially since she was offered only $3.00 per week with meals but no board. She tried to look up Jack Manly, her one-time lover, but he was nowhere to be found. Perchance, too, he would not have known her; for in her poverty she had perforce become a brunette again, and Jack had not beheld her in that state since school days. One day she found a neat but costly purse in the park; and after seeing that there was not much in it, took it to the rich lady whose card proclaimed her ownership. Delighted beyond words at the honesty of this forlorn waif, the aristocratic Mrs. Van Itty adopted Ermengarde to replace the little one who had been stolen from her so many years ago. “How like my precious Maude,” she sighed, as she watched the fair brunette return to blondeness. And so several weeks passed, with the old folks at home tearing their hair and the wicked ’Squire Hardman chuckling devilishly.

Chapter VII

Happy Ever Afterward

One day the wealthy heiress Ermengarde S. Van Itty hired a new second assistant chauffeur. Struck by something familiar in his face, she looked again and gasped. Lo! it was none other than the perfidious Algernon Reginald Jones, whom she had pushed from a car window on that fateful day! He had survived—this much was almost immediately evident. Also, he had wed the other woman, who had run away with the milkman and all the money in the house. Now wholly humbled, he asked forgiveness of our heroine, and confided to her the whole tale of the gold on her father’s farm. Moved beyond words, she raised his salary a dollar a month and resolved to gratify at last that always unquenchable anxiety to relieve the worry of the old folks. So one bright day Ermengarde motored back to Hogton and arrived at the farm just as ’Squire Hardman was foreclosing the mortgage and ordering the old folks out.

“Stay, villain!” she cried, flashing a colossal roll of bills. “You are foiled at last! Here is your money—now go, and never darken our humble door again!”

Then followed a joyous reunion, whilst the ’squire twisted his moustache and riding-crop in bafflement and dismay. But hark! What is this? Footsteps sound on the old gravel walk, and who should appear but our hero, Jack Manly—worn and seedy, but radiant of face. Seeking at once the downcast villain, he said:

“’Squire—lend me a ten-spot, will you? I have just come back from the city with my beauteous bride, the fair Bridget Goldstein, and need something to start things on the old farm.” Then turning to the Stubbses, he apologised for his inability to pay off the mortgage as agreed.

“Don’t mention it,” said Ermengarde, “prosperity has come to us, and I will consider it sufficient payment if you will forget forever the foolish fancies of our childhood.”

All this time Mrs. Van Itty had been sitting in the motor waiting for Ermengarde; but as she lazily eyed the sharp-faced Hannah Stubbs a vague memory started from the back of her brain. Then it all came to her, and she shrieked accusingly at the agrestic matron.

“You—you—Hannah Smith—I know you now! Twenty-eight years ago you were my baby Maude’s nurse and stole her from the cradle!! Where, oh, where is my child?” Then a thought came as the lightning in a murky sky. “Ermengarde—you say she is your daughter. . . . She is mine! Fate has restored to me my old chee-ild—my tiny Maudie!—Ermengarde—Maude—come to your mother’s loving arms!!!”

But Ermengarde was doing some tall thinking. How could she get away with the sixteen-year-old stuff if she had been stolen twenty-eight years ago? And if she was not Stubbs’ daughter the gold would never be hers. Mrs. Van Itty was rich, but ’Squire Hardman was richer. So, approaching the dejected villain, she inflicted upon him the last terrible punishment.

“’Squire, dear,” she murmured, “I have reconsidered all. I love you and your naive strength. Marry me at once or I will have you prosecuted for that kidnapping last year. Foreclose your mortgage and enjoy with me the gold your cleverness discovered. Come, dear!” And the poor dub did.

THE END

Sweet Ermengarde

Or, The Heart of a Country Girl (1917)

By Percy Simple [H. P. Lovecraft (1890 – 1937)]

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Lovecraft, H.P., Tales of Mystery & Imagination