Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Voltaire

(1694-1778)

A Mme du Châtelet

” Si vous voulez que j’aime encore,

Rendez-moi l’âge des amours ;

Au crépuscule de mes jours

Rejoignez, s’il se peut, l’aurore.

Des beaux lieux où le dieu du vin

Avec l’Amour tient son empire,

Le Temps, qui me prend par la main,

M’avertit que je me retire.

De son inflexible rigueur

Tirons au moins quelque avantage.

Qui n’a pas l’esprit de son âge,

De son âge a tout le malheur.

Laissons à la belle jeunesse

Ses folâtres emportements.

Nous ne vivons que deux moments :

Qu’il en soit un pour la sagesse.

Quoi ! pour toujours vous me fuyez,

Tendresse, illusion, folie,

Dons du ciel, qui me consoliez

Des amertumes de la vie !

On meurt deux fois, je le vois bien :

Cesser d’aimer et d’être aimable,

C’est une mort insupportable ;

Cesser de vivre, ce n’est rien. “

Ainsi je déplorais la perte

Des erreurs de mes premiers ans ;

Et mon âme, aux désirs ouverte,

Regrettait ses égarements.

Du ciel alors daignant descendre,

L’Amitié vint à mon secours ;

Elle était peut-être aussi tendre,

Mais moins vive que les Amours.

Touché de sa beauté nouvelle,

Et de sa lumière éclairé,

Je la suivis; mais je pleurai

De ne pouvoir plus suivre qu’elle.

Voltaire poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, MONTAIGNE, Voltaire

VPRO BOEKEN met Bob den Uyl Prijs winnaar 2014 = Zondag 25 mei 2014 om 10.30 uur in VPRO Boeken, TV Nederland 1

VPRO BOEKEN met Bob den Uyl Prijs winnaar 2014 = Zondag 25 mei 2014 om 10.30 uur in VPRO Boeken, TV Nederland 1

Wim Brands ontvangt aanstaande zondag de winnaar/winnares van de VPRO Bob den Uyl Prijs 2014, die op zaterdag 24 mei bekend wordt gemaakt tijdens het VPRO neemt–je -mee evenement in Pakhuis de Zwijger in Amsterdam.

De genomineerden van dit jaar zijn:

Joris van Casteren – Het been in de IJssel (Prometheus);

Marcel van Engelen – Het kasteel van Elmina (De Bezige Bij);

Raoul de Jong – De grootsheid van het al (Thomas Rap);

Lieve Joris – Op de vleugels van de draak (AtlasContact);

Rudi Rotthier – De naakte perenboom (AtlasContact);

Laura Starink – Duitse wortels (AtlasContact)

# Meer informatie op website VPRO BOEKEN

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, The talk of the town

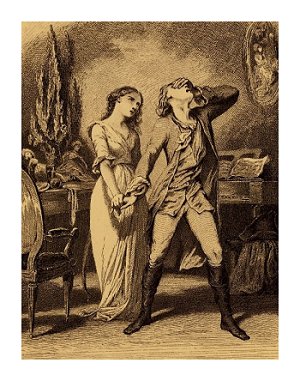

The Sorrows of Young Werther (36) by J.W. von Goethe

JANUARY 8, 1772.

What beings are men, whose whole thoughts are occupied with form and

ceremony, who for years together devote their mental and physical

exertions to the task of advancing themselves but one step, and

endeavouring to occupy a higher place at the table. Not that such

persons would otherwise want employment: on the contrary, they give

themselves much trouble by neglecting important business for such petty

trifles. Last week a question of precedence arose at a sledging-party,

and all our amusement was spoiled.

The silly creatures cannot see that it is not place which constitutes

real greatness, since the man who occupies the first place but

seldom plays the principal part. How many kings are governed by their

ministers–how many ministers by their secretaries? Who, in such cases,

is really the chief? He, as it seems to me, who can see through the

others, and possesses strength or skill enough to make their power or

passions subservient to the execution of his own designs.

JANUARY 20.

I must write to you from this place, my dear Charlotte, from a small

room in a country inn, where I have taken shelter from a severe storm.

During my whole residence in that wretched place D–, where I lived

amongst strangers,–strangers, indeed, to this heart,–I never at any

time felt the smallest inclination to correspond with you; but in this

cottage, in this retirement, in this solitude, with the snow and hail

beating against my lattice-pane, you are my first thought. The instant

I entered, your figure rose up before me, and the remembrance! O my

Charlotte, the sacred, tender remembrance! Gracious Heaven! restore to

me the happy moment of our first acquaintance.

Could you but see me, my dear Charlotte, in the whirl of

dissipation,–how my senses are dried up, but my heart is at no time

full. I enjoy no single moment of happiness: all is vain–nothing

touches me. I stand, as it were, before the raree-show: I see the little

puppets move, and I ask whether it is not an optical illusion. I am

amused with these puppets, or, rather, I am myself one of them: but,

when I sometimes grasp my neighbour’s hand, I feel that it is not

natural; and I withdraw mine with a shudder. In the evening I say I will

enjoy the next morning’s sunrise, and yet I remain in bed: in the day I

promise to ramble by moonlight; and I, nevertheless, remain at home. I

know not why I rise, nor why I go to sleep.

The leaven which animated my existence is gone: the charm which cheered

me in the gloom of night, and aroused me from my morning slumbers, is

for ever fled.

I have found but one being here to interest me, a Miss B–. She

resembles you, my dear Charlotte, if any one can possibly resemble you.

“Ah!” you will say, “he has learned how to pay fine compliments.” And

this is partly true. I have been very agreeable lately, as it was not

in my power to be otherwise. I have, moreover, a deal of wit: and the

ladies say that no one understands flattery better, or falsehoods you

will add; since the one accomplishment invariably accompanies the

other. But I must tell you of Miss B–. She has abundance of soul,

which flashes from her deep blue eyes. Her rank is a torment to her, and

satisfies no one desire of her heart. She would gladly retire from

this whirl of fashion, and we often picture to ourselves a life of

undisturbed happiness in distant scenes of rural retirement: and then we

speak of you, my dear Charlotte; for she knows you, and renders homage

to your merits; but her homage is not exacted, but voluntary, she loves

you, and delights to hear you made the subject of conversation.

Oh, that I were sitting at your feet in your favourite little room, with

the dear children playing around us! If they became troublesome to you,

I would tell them some appalling goblin story; and they would crowd

round me with silent attention. The sun is setting in glory; his last

rays are shining on the snow, which covers the face of the country: the

storm is over, and I must return to my dungeon. Adieu!–Is Albert with

you? and what is he to you? God forgive the question.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

The Sorrows of Young Werther (35) by J.W. von Goethe

DECEMBER 24.

As I anticipated, the ambassador occasions me infinite annoyance. He is

the most punctilious blockhead under heaven. He does everything step by

step, with the trifling minuteness of an old woman; and he is a man whom

it is impossible to please, because he is never pleased with himself. I

like to do business regularly and cheerfully, and, when it is finished,

to leave it. But he constantly returns my papers to me, saying, “They

will do,” but recommending me to look over them again, as “one may

always improve by using a better word or a more appropriate particle.”

I then lose all patience, and wish myself at the devil’s. Not a

conjunction, not an adverb, must be omitted: he has a deadly antipathy

to all those transpositions of which I am so fond; and, if the music

of our periods is not tuned to the established, official key, he cannot

comprehend our meaning. It is deplorable to be connected with such a

fellow.

My acquaintance with the Count C–is the only compensation for such an

evil. He told me frankly, the other day, that he was much displeased

with the difficulties and delays of the ambassador; that people like him

are obstacles, both to themselves and to others. “But,” added he, “one

must submit, like a traveller who has to ascend a mountain: if the

mountain was not there, the road would be both shorter and pleasanter;

but there it is, and he must get over it.”

The old man perceives the count’s partiality for me: this annoys him,

and, he seizes every opportunity to depreciate the count in my hearing.

I naturally defend him, and that only makes matters worse. Yesterday he

made me indignant, for he also alluded to me. “The count,” he said, “is

a man of the world, and a good man of business: his style is good,

and he writes with facility; but, like other geniuses, he has no solid

learning.” He looked at me with an expression that seemed to ask if I

felt the blow. But it did not produce the desired effect: I despise a

man who can think and act in such a manner. However, I made a stand, and

answered with not a little warmth. The count, I said, was a man entitled

to respect, alike for his character and his acquirements. I had never

met a person whose mind was stored with more useful and extensive

knowledge,–who had, in fact, mastered such an infinite variety of

subjects, and who yet retained all his activity for the details of

ordinary business. This was altogether beyond his comprehension; and I

took my leave, lest my anger should be too highly excited by some new

absurdity of his.

And you are to blame for all this, you who persuaded me to bend my

neck to this yoke by preaching a life of activity to me. If the man who

plants vegetables, and carries his corn to town on market-days, is not

more usefully employed than I am, then let me work ten years longer at

the galleys to which I am now chained.

Oh, the brilliant wretchedness, the weariness, that one is doomed

to witness among the silly people whom we meet in society here! The

ambition of rank! How they watch, how they toil, to gain precedence!

What poor and contemptible passions are displayed in their utter

nakedness! We have a woman here, for example, who never ceases to

entertain the company with accounts of her family and her estates. Any

stranger would consider her a silly being, whose head was turned by

her pretensions to rank and property; but she is in reality even

more ridiculous, the daughter of a mere magistrate’s clerk from this

neighbourhood. I cannot understand how human beings can so debase

themselves.

Every day I observe more and more the folly of judging of others by

ourselves; and I have so much trouble with myself, and my own heart is

in such constant agitation, that I am well content to let others pursue

their own course, if they only allow me the same privilege.

What provokes me most is the unhappy extent to which distinctions of

rank are carried. I know perfectly well how necessary are inequalities

of condition, and I am sensible of the advantages I myself derive

therefrom; but I would not have these institutions prove a barrier to

the small chance of happiness which I may enjoy on this earth.

I have lately become acquainted with a Miss B–, a very agreeable girl,

who has retained her natural manners in the midst of artificial life.

Our first conversation pleased us both equally; and, at taking leave,

I requested permission to visit her. She consented in so obliging a

manner, that I waited with impatience for the arrival of the happy

moment. She is not a native of this place, but resides here with her

aunt. The countenance of the old lady is not prepossessing. I paid her

much attention, addressing the greater part of my conversation to her;

and, in less than half an hour, I discovered what her niece subsequently

acknowledged to me, that her aged aunt, having but a small fortune, and

a still smaller share of understanding, enjoys no satisfaction except

in the pedigree of her ancestors, no protection save in her noble birth,

and no enjoyment but in looking from her castle over the heads of the

humble citizens. She was, no doubt, handsome in her youth, and in her

early years probably trifled away her time in rendering many a poor

youth the sport of her caprice: in her riper years she has submitted

to the yoke of a veteran officer, who, in return for her person and her

small independence, has spent with her what we may designate her age of

brass. He is dead; and she is now a widow, and deserted. She spends her

iron age alone, and would not be approached, except for the loveliness

of her niece.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

The Sorrows of Young Werther (34)

by J.W. von Goethe

BOOK II.

OCTOBER 20.

We arrived here yesterday. The ambassador is indisposed, and will not

go out for some days. If he were less peevish and morose, all would

be well. I see but too plainly that Heaven has destined me to severe

trials; but courage! a light heart may bear anything. A light heart!

I smile to find such a word proceeding from my pen. A little more

lightheartedness would render me the happiest being under the sun.

But must I despair of my talents and faculties, whilst others of far

inferior abilities parade before me with the utmost self-satisfaction?

Gracious Providence, to whom I owe all my powers, why didst thou not

withhold some of those blessings I possess, and substitute in their

place a feeling of self-confidence and contentment?

But patience! all will yet be well; for I assure you, my dear friend,

you were right: since I have been obliged to associate continually with

other people, and observe what they do, and how they employ themselves,

I have become far better satisfied with myself. For we are so

constituted by nature, that we are ever prone to compare ourselves with

others; and our happiness or misery depends very much on the objects

and persons around us. On this account, nothing is more dangerous than

solitude: there our imagination, always disposed to rise, taking a new

flight on the wings of fancy, pictures to us a chain of beings of whom

we seem the most inferior. All things appear greater than they really

are, and all seem superior to us. This operation of the mind is quite

natural: we so continually feel our own imperfections, and fancy we

perceive in others the qualities we do not possess, attributing to them

also all that we enjoy ourselves, that by this process we form the idea

of a perfect, happy man,--a man, however, who only exists in our own

imagination.

But when, in spite of weakness and disappointments, we set to work in

earnest, and persevere steadily, we often find, that, though obliged

continually to tack, we make more way than others who have the

assistance of wind and tide; and, in truth, there can be no greater

satisfaction than to keep pace with others or outstrip them in the race.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (34)

by J.W. von Goethe

BOOK II.

OCTOBER 20.

We arrived here yesterday. The ambassador is indisposed, and will not

go out for some days. If he were less peevish and morose, all would

be well. I see but too plainly that Heaven has destined me to severe

trials; but courage! a light heart may bear anything. A light heart!

I smile to find such a word proceeding from my pen. A little more

lightheartedness would render me the happiest being under the sun.

But must I despair of my talents and faculties, whilst others of far

inferior abilities parade before me with the utmost self-satisfaction?

Gracious Providence, to whom I owe all my powers, why didst thou not

withhold some of those blessings I possess, and substitute in their

place a feeling of self-confidence and contentment?

But patience! all will yet be well; for I assure you, my dear friend,

you were right: since I have been obliged to associate continually with

other people, and observe what they do, and how they employ themselves,

I have become far better satisfied with myself. For we are so

constituted by nature, that we are ever prone to compare ourselves with

others; and our happiness or misery depends very much on the objects

and persons around us. On this account, nothing is more dangerous than

solitude: there our imagination, always disposed to rise, taking a new

flight on the wings of fancy, pictures to us a chain of beings of whom

we seem the most inferior. All things appear greater than they really

are, and all seem superior to us. This operation of the mind is quite

natural: we so continually feel our own imperfections, and fancy we

perceive in others the qualities we do not possess, attributing to them

also all that we enjoy ourselves, that by this process we form the idea

of a perfect, happy man,--a man, however, who only exists in our own

imagination.

But when, in spite of weakness and disappointments, we set to work in

earnest, and persevere steadily, we often find, that, though obliged

continually to tack, we make more way than others who have the

assistance of wind and tide; and, in truth, there can be no greater

satisfaction than to keep pace with others or outstrip them in the race.

November 26.

I begin to find my situation here more tolerable, considering all

circumstances. I find a great advantage in being much occupied; and the

number of persons I meet, and their different pursuits, create a varied

entertainment for me. I have formed the acquaintance of the Count

C--and I esteem him more and more every day. He is a man of strong

understanding and great discernment; but, though he sees farther than

other people, he is not on that account cold in his manner, but capable

of inspiring and returning the warmest affection. He appeared interested

in me on one occasion, when I had to transact some business with him. He

perceived, at the first word, that we understood each other, and that

he could converse with me in a different tone from what he used with

others. I cannot sufficiently esteem his frank and open kindness to me.

It is the greatest and most genuine of pleasures to observe a great mind

in sympathy with our own.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

November 26.

I begin to find my situation here more tolerable, considering all

circumstances. I find a great advantage in being much occupied; and the

number of persons I meet, and their different pursuits, create a varied

entertainment for me. I have formed the acquaintance of the Count

C--and I esteem him more and more every day. He is a man of strong

understanding and great discernment; but, though he sees farther than

other people, he is not on that account cold in his manner, but capable

of inspiring and returning the warmest affection. He appeared interested

in me on one occasion, when I had to transact some business with him. He

perceived, at the first word, that we understood each other, and that

he could converse with me in a different tone from what he used with

others. I cannot sufficiently esteem his frank and open kindness to me.

It is the greatest and most genuine of pleasures to observe a great mind

in sympathy with our own.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazineMore in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

The Sorrows of Young Werther (33) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ SEPTEMBER 10. ♦ Oh, what a night, Wilhelm! I can henceforth bear anything. I shall never see her again. Oh, why cannot I fall on your neck, and, with floods of tears and raptures, give utterance to all the passions which distract my heart! Here I sit gasping for breath, and struggling to compose myself.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (33) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ SEPTEMBER 10. ♦ Oh, what a night, Wilhelm! I can henceforth bear anything. I shall never see her again. Oh, why cannot I fall on your neck, and, with floods of tears and raptures, give utterance to all the passions which distract my heart! Here I sit gasping for breath, and struggling to compose myself.

I wait for day, and at sunrise the horses are to be at the door. And she is sleeping calmly, little suspecting that she has seen me for the last time. I am free. I have had the courage, in an interview of two hours’ duration, not to betray my intention. And O Wilhelm, what a conversation it was!

Albert had promised to come to Charlotte in the garden immediately after supper. I was upon the terrace under the tall chestnut trees, and watched the setting sun. I saw him sink for the last time beneath this delightful valley and silent stream. I had often visited the same spot with Charlotte, and witnessed that glorious sight; and now–I was walking up and down the very avenue which was so dear to me. A secret sympathy had frequently drawn me thither before I knew Charlotte; and we were delighted when, in our early acquaintance, we discovered that we each loved the same spot, which is indeed as romantic as any that ever captivated the fancy of an artist.

From beneath the chestnut trees, there is an extensive view. But I remember that I have mentioned all this in a former letter, and have described the tall mass of beech trees at the end, and how the avenue grows darker and darker as it winds its way among them, till it ends in a gloomy recess, which has all the charm of a mysterious solitude. I still remember the strange feeling of melancholy which came over me the first time I entered that dark retreat, at bright midday. I felt some secret foreboding that it would, one day, be to me the scene of some happiness or misery.

I had spent half an hour struggling between the contending thoughts of going and returning, when I heard them coming up the terrace. I ran to meet them. I trembled as I took her hand, and kissed it. As we reached the top of the terrace, the moon rose from behind the wooded hill. We conversed on many subjects, and, without perceiving it, approached the gloomy recess. Charlotte entered, and sat down. Albert seated himself beside her. I did the same, but my agitation did not suffer me to remain long seated. I got up, and stood before her, then walked backward and forward, and sat down again. I was restless and miserable. Charlotte drew our attention to the beautiful effect of the moonlight, which threw a silver hue over the terrace in front of us, beyond the beech trees.

It was a glorious sight, and was rendered more striking by the darkness which surrounded the spot where we were. We remained for some time silent, when Charlotte observed, “Whenever I walk by moonlight, it brings to my remembrance all my beloved and departed friends, and I am filled with thoughts of death and futurity. We shall live again, Werther!” she continued, with a firm but feeling voice; “but shall we know one another again what do you think? what do you say?”

“Charlotte,” I said, as I took her hand in mine, and my eyes filled with tears, “we shall see each other again–here and hereafter we shall meet again.” I could say no more. Why, Wilhelm, should she put this question to me, just at the moment when the fear of our cruel separation filled my heart?

“Charlotte,” I said, as I took her hand in mine, and my eyes filled with tears, “we shall see each other again–here and hereafter we shall meet again.” I could say no more. Why, Wilhelm, should she put this question to me, just at the moment when the fear of our cruel separation filled my heart?

“And oh! do those departed ones know how we are employed here? do they know when we are well and happy? do they know when we recall their memories with the fondest love? In the silent hour of evening the shade of my mother hovers around me; when seated in the midst of my children,

I see them assembled near me, as they used to assemble near her; and then I raise my anxious eyes to heaven, and wish she could look down upon us, and witness how I fulfil the promise I made to her in her last moments, to be a mother to her children. With what emotion do I then exclaim, ‘Pardon, dearest of mothers, pardon me, if I do not adequately supply your place! Alas! I do my utmost. They are clothed and fed; and, still better, they are loved and educated. Could you but see, sweet saint! the peace and harmony that dwells amongst us, you would glorify God with the warmest feelings of gratitude, to whom, in your last hour, you addressed such fervent prayers for our happiness.'” Thus did she express herself; but O Wilhelm! who can do justice to her language? how can cold and passionless words convey the heavenly expressions of the spirit? Albert interrupted her gently. “This affects you too deeply, my dear Charlotte. I know your soul dwells on such recollections with intense delight; but I implore–” “O Albert!” she continued, “I am sure you do not forget the evenings when we three used to sit at the little round table, when papa was absent, and the little ones had retired. You often had a good book with you, but seldom read it; the conversation of that noble being was preferable to everything,–that beautiful, bright, gentle, and yet ever-toiling woman. God alone knows how I have supplicated with tears on my nightly couch, that I might be like her.”

I threw myself at her feet, and, seizing her hand, bedewed it with a thousand tears. “Charlotte!” I exclaimed, “God’s blessing and your mother’s spirit are upon you.” “Oh! that you had known her,” she said, with a warm pressure of the hand. “She was worthy of being known to you.” I thought I should have fainted: never had I received praise so flattering. She continued, “And yet she was doomed to die in the flower of her youth, when her youngest child was scarcely six months old. Her illness was but short, but she was calm and resigned; and it was only for her children, especially the youngest, that she felt unhappy. When her end drew nigh, she bade me bring them to her. I obeyed. The younger ones knew nothing of their approaching loss, while the elder ones were quite overcome with grief. They stood around the bed; and she raised her feeble hands to heaven, and prayed over them; then, kissing them in turn, she dismissed them, and said to me, ‘Be you a mother to them.’

I gave her my hand. ‘You are promising much, my child,’ she said: ‘a mother’s fondness and a mother’s care! I have often witnessed, by your tears of gratitude, that you know what is a mother’s tenderness: show it to your brothers and sisters, and be dutiful and faithful to your father as a wife; you will be his comfort.’ She inquired for him. He had retired to conceal his intolerable anguish,–he was heartbroken, ‘Albert, you were in the room.’ She heard some one moving: she inquired who it was, and desired you to approach. She surveyed us both with a look of composure and satisfaction, expressive of her conviction that we should be happy,–happy with one another.” Albert fell upon her neck, and kissed her, and exclaimed, “We are so, and we shall be so!” Even Albert, generally so tranquil, had quite lost his composure; and I was excited beyond expression.

I gave her my hand. ‘You are promising much, my child,’ she said: ‘a mother’s fondness and a mother’s care! I have often witnessed, by your tears of gratitude, that you know what is a mother’s tenderness: show it to your brothers and sisters, and be dutiful and faithful to your father as a wife; you will be his comfort.’ She inquired for him. He had retired to conceal his intolerable anguish,–he was heartbroken, ‘Albert, you were in the room.’ She heard some one moving: she inquired who it was, and desired you to approach. She surveyed us both with a look of composure and satisfaction, expressive of her conviction that we should be happy,–happy with one another.” Albert fell upon her neck, and kissed her, and exclaimed, “We are so, and we shall be so!” Even Albert, generally so tranquil, had quite lost his composure; and I was excited beyond expression.

“And such a being,” She continued, “was to leave us, Werther! Great God, must we thus part with everything we hold dear in this world? Nobody felt this more acutely than the children: they cried and lamented for a long time afterward, complaining that men had carried away their dear mamma.”

Charlotte rose. It aroused me; but I continued sitting, and held her hand. “Let us go,” she said: “it grows late.” She attempted to withdraw her hand: I held it still. “We shall see each other again,” I exclaimed: “we shall recognise each other under every possible change! I am going,”

I continued, “going willingly; but, should I say for ever, perhaps I may not keep my word. Adieu, Charlotte; adieu, Albert. We shall meet again.” “Yes: tomorrow, I think,” she answered with a smile. Tomorrow! how I felt the word! Ah! she little thought, when she drew her hand away from mine. They walked down the avenue. I stood gazing after them in the moonlight. I threw myself upon the ground, and wept: I then sprang up, and ran out upon the terrace, and saw, under the shade of the linden-trees, her white dress disappearing near the garden-gate. I stretched out my arms, and she vanished.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Hafid Bouazza &

Koos Neuvel

in VPRO BOEKEN

Hafid Bouazza – Meriswin

Een man wordt opgenomen in het ziekenhuis met een delirium: ‘Nu kwam de eerste aanval van portale bloeding, het resultaat van portale hypertensie: een massale bloeding spatte uit zijn ingewanden naar buiten, een ware stroom, een rozen- en viooltjesvloed van Heliogabalus, op heuvelhoogte’.

Koos Neuvel – ‘Alzheimer. Biografie van een ziekte’

Herinneren en de werking van het geheugen lopen overigens als een rode draad door deze aflevering van Boeken want de tweede gast op deze zondagochtend is wetenschapsjournalist Koos Neuvel die een geschiedenis van de ziekte van deze tijd schreef: Alzheimer.

Deze aflevering van VPRO Boeken is zondag 4 mei 2014 te zien om 11.20 uur op Nederland 1

# meer info VPRO BOEKEN website

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News

The Sorrows of Young Werther (32) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ AUGUST 30. ♦ Unhappy being that I am! Why do I thus deceive myself? What is to come of all this wild, aimless, endless passion? I cannot pray except to her.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (32) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ AUGUST 30. ♦ Unhappy being that I am! Why do I thus deceive myself? What is to come of all this wild, aimless, endless passion? I cannot pray except to her.

My imagination sees nothing but her: all surrounding objects are of no account, except as they relate to her. In this dreamy state I enjoy many happy hours, till at length I feel compelled to tear myself away from her. Ah, Wilhelm, to what does not my heart often compel me! When I have spent several hours in her company, till I feel completely absorbed by her figure, her grace, the divine expression of her thoughts, my mind becomes gradually excited to the highest excess, my sight grows dim, my hearing confused, my breathing oppressed as if by the hand of a murderer, and my beating heart seeks to obtain relief for my aching senses. I am sometimes unconscious whether I really exist. If in such moments I find no sympathy, and Charlotte does not allow me to enjoy the melancholy consolation of bathing her hand with my tears, I feel compelled to tear myself from her, when I either wander through the country, climb some precipitous cliff, or force a path through the trackless thicket, where I am lacerated and torn by thorns and briers; and thence I find relief. Sometimes I lie stretched on the ground, overcome with  fatigue and dying with thirst; sometimes, late in the night, when the moon shines above me, I recline against an aged tree in some sequestered forest, to rest my weary limbs, when, exhausted and worn, I sleep till break of day. O Wilhelm! the hermit’s cell, his sackcloth, and girdle of thorns would be luxury and indulgence compared with what I suffer. Adieu! I see no end to this wretchedness except the grave.

fatigue and dying with thirst; sometimes, late in the night, when the moon shines above me, I recline against an aged tree in some sequestered forest, to rest my weary limbs, when, exhausted and worn, I sleep till break of day. O Wilhelm! the hermit’s cell, his sackcloth, and girdle of thorns would be luxury and indulgence compared with what I suffer. Adieu! I see no end to this wretchedness except the grave.

♦ SEPTEMBER 3. ♦ I must away. Thank you, Wilhelm, for determining my wavering purpose. For a whole fortnight I have thought of leaving her. I must away. She has returned to town, and is at the house of a friend. And then, Albert–yes, I must go.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

The Sorrows of Young Werther (31) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ AUGUST 28. ♦ If my ills would admit of any cure, they would certainly be cured here. This is my birthday, and early in the morning I received a packet from Albert. Upon opening it, I found one of the pink ribbons which Charlotte wore in her dress the first time I saw her, and which I had several times asked her to give me. With it were two volumes in duodecimo of Wetstein’s “Homer,” a book I had often wished for, to save me the inconvenience of carrying the large Ernestine edition with me upon my walks. You see how they anticipate my wishes, how well they understand all those little attentions of friendship, so superior to the costly presents of the great, which are humiliating. I kissed the ribbon a thousand times, and in every breath inhaled the remembrance of those happy and irrevocable days which filled me with the keenest joy. Such, Wilhelm, is our fate. I do not murmur at it: the flowers of life are but visionary. How many pass away, and leave no trace behind–how few yield any fruit–and the fruit itself, how rarely does it ripen! And yet there are flowers enough! and is it not strange, my friend, that we should suffer the little that does really ripen, to rot, decay, and perish unenjoyed? Farewell! This is a glorious summer. I often climb into the trees in Charlotte’s orchard, and shake down the pears that hang on the highest branches. She stands below, and catches them as they fall.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (31) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ AUGUST 28. ♦ If my ills would admit of any cure, they would certainly be cured here. This is my birthday, and early in the morning I received a packet from Albert. Upon opening it, I found one of the pink ribbons which Charlotte wore in her dress the first time I saw her, and which I had several times asked her to give me. With it were two volumes in duodecimo of Wetstein’s “Homer,” a book I had often wished for, to save me the inconvenience of carrying the large Ernestine edition with me upon my walks. You see how they anticipate my wishes, how well they understand all those little attentions of friendship, so superior to the costly presents of the great, which are humiliating. I kissed the ribbon a thousand times, and in every breath inhaled the remembrance of those happy and irrevocable days which filled me with the keenest joy. Such, Wilhelm, is our fate. I do not murmur at it: the flowers of life are but visionary. How many pass away, and leave no trace behind–how few yield any fruit–and the fruit itself, how rarely does it ripen! And yet there are flowers enough! and is it not strange, my friend, that we should suffer the little that does really ripen, to rot, decay, and perish unenjoyed? Farewell! This is a glorious summer. I often climb into the trees in Charlotte’s orchard, and shake down the pears that hang on the highest branches. She stands below, and catches them as they fall.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Boudewijn Smits

VPRO boeken

Uitzending zondag 27 april 2014 om 11.20 uur op Nederland 1

Boudewijn Smits is historicus en schreef de biografie Loe de Jong, 1914-2005, Historicus met een missie.

Dr. Loe de Jong heeft als geen ander de beeldvorming van het Nederlandse volk over het oorlogsverleden gedomineerd. Een telefoonboek van de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Zo omschrijft historicus Boudewijn Smits het monumentale werk van Loe de Jong, de twaalf delen over Nederland tijdens de tweede wereldoorlog.

# meer informatie op website vproboeken

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, BIOGRAPHY

The Sorrows of Young Werther (30) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ AUGUST 21. ♦ In vain do I stretch out my arms toward her when I awaken in the morning from my weary slumbers. In vain do I seek for her at night in my bed, when some innocent dream has happily deceived me, and placed her near me in the fields, when I have seized her hand and covered it with countless kisses. And when I feel for her in the half confusion of sleep, with the happy sense that she is near, tears flow from my oppressed heart; and, bereft of all comfort, I weep over my future woes.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (30) by J.W. von Goethe ♦ AUGUST 21. ♦ In vain do I stretch out my arms toward her when I awaken in the morning from my weary slumbers. In vain do I seek for her at night in my bed, when some innocent dream has happily deceived me, and placed her near me in the fields, when I have seized her hand and covered it with countless kisses. And when I feel for her in the half confusion of sleep, with the happy sense that she is near, tears flow from my oppressed heart; and, bereft of all comfort, I weep over my future woes.

♦ AUGUST 22. ♦ What a misfortune, Wilhelm! My active spirits have degenerated into contented indolence. I cannot be idle, and yet I am unable to set to work. I cannot think: I have no longer any feeling for the beauties of nature, and books are distasteful to me. Once we give ourselves up, we are totally lost. Many a time and oft I wish I were a common labourer; that, awakening in the morning, I might have but one prospect, one pursuit,  one hope, for the day which has dawned. I often envy Albert when I see him buried in a heap of papers and parchments, and I fancy I should be happy were I in his place. Often impressed with this feeling I have been on the point of writing to you and to the minister, for the appointment at the embassy, which you think I might obtain. I believe I might procure it. The minister has long shown a regard for me, and has frequently urged me to seek employment. It is the business of an hour only. Now and then the fable of the horse recurs to me. Weary of liberty, he suffered himself to be saddled and bridled, and was ridden to death for his pains. I know not what to determine upon. For is not this anxiety for change the consequence of that restless spirit which would pursue me equally in every situation of life?

one hope, for the day which has dawned. I often envy Albert when I see him buried in a heap of papers and parchments, and I fancy I should be happy were I in his place. Often impressed with this feeling I have been on the point of writing to you and to the minister, for the appointment at the embassy, which you think I might obtain. I believe I might procure it. The minister has long shown a regard for me, and has frequently urged me to seek employment. It is the business of an hour only. Now and then the fable of the horse recurs to me. Weary of liberty, he suffered himself to be saddled and bridled, and was ridden to death for his pains. I know not what to determine upon. For is not this anxiety for change the consequence of that restless spirit which would pursue me equally in every situation of life?

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Ton van Reen: Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam (27 – slot)

Ton van Reen: Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam (27 – slot)

♦ Het einde ♦

De klok sloeg drie uur. De nacht sleepte zich voort, maar de stad bleef een bron van vals licht en lawaai.

Alleen in De Engelbewaarder was het rustig. Zelfs de muizen gaven zich over aan de rust, hoewel ze eigenlijk nachtdiertjes waren. Hun tijdsindeling was in het café in de war geraakt. Slechts de critolis bleek weinig last van de nacht te hebben. Juist deze rust wekte haar op fraaier te bloeien. Haar kleuren uitdagender dan ooit tevoren.

Met tact en geduld werkte Bas de laatste klanten de deur uit. De stille drinkers, die nooit zin hadden om naar huis te gaan. Nachtbrakers die pas konden slapen als ze het eerste ochtendlicht hadden gezien, bang als ze waren voor de nacht en zijn mysteries. Het soort jongens waar hij ook nooit echt contact mee had. Ze kwamen altijd pas op het allerlaatste moment binnensluipen, niet veel eerder dan sluitingstijd. Ze rekenden erop dat ze nog wel een paar pilsjes lang konden blijven zitten. Eenzaten. Dromers, met het voorkomen van teringlijders. Als ze om een uur of vijf uit het laatst sluitende nachtcafé waren gezet, zochten ze de koffietentjes op die het eerst opengingen.

Bas sloot de deur, poetste het koper van de bierpomp glimmend op, kraste wat vuil uit de scheuren in het blad van de bar en spoelde het zink. Hij wilde alles in goede orde achterlaten. Hij hield niet van troep in zijn zaak als hij ‘s ochtends weer moest beginnen. Hij gaapte. Hij was hondsmoe. Deze krankzinnige dag was hem niet in de koude kleren gaan zitten. En het was veel later geworden dan gewoonlijk.

Er werd op de deur gebonsd. Zeker iemand die nog licht had gezien en het nog even wilde proberen.

Bas slofte naar de deur en deed hem op een kier open. Crazy, Mireille en een tweetal dat hij niet kende. Ze zagen er afgemat uit.

`Wat geeft me de eer in deze kleine uurtjes?’ vroeg Bas. Hij verwachtte geen antwoord. Hij begreep dat hij iets voor hen moest doen.

`Koffie’, zei Crazy. `Dat zou al heel wat zijn.’

`Ik ben de slaaf van iedereen’, zei Bas om te verbloemen dat hij het goed met hen voor had. Hij liep al naar de koffiemachine. Terwijl hij de kopjes onder de kraan schoof, merkte hij dat de muizen zich eigenaardig gedroegen. Waren de meesten al lui aan de kant gaan liggen, nu leken ze door het een of ander onrustig te zijn geworden. Ze dromden samen in groepjes en waren druk met elkaar in gesprek.

Plotseling schoot Kaspar krijsend uit de kelder. Hij leek helemaal gek te zijn geworden. Als een schicht schoot hij door het café, razend, alsof hij een delirium had. Hij gilde. Hij was zo door het dolle heen dat het even duurde voordat Bas begreep dat hij het tegen de grijze muizen had. Hij bedreigde hen. Hij wilde dat ze onmiddellijk uit het pand zouden verdwijnen, anders zou hij hen stuk voor stuk de strot doorbijten. Hij meende het echt. Hij was in een moordzuchtige stemming.

Bang maar gehoorzaam kwamen de grijze muizen tevoorschijn. Je kon aan hen zien waarom ze nooit sterk zouden worden. Ze waren zachtaardig en konden niet van zich afbijten. Mak als lammetjes liepen ze naar de deur.

Bas werd kwaad.

`Ik ben te goed voor je geweest’, riep hij naar Kaspar. `Jij denkt dat goedheid een plicht is.’

`Je wilt toch niet dat wij honger moeten lijden voor weer een ander zootje!’ gilde Kaspar. `Ze hebben hele gaten in de voorraad kaas gevreten.’

`Jíj hebt te veel gevreten’, riep Bas. `Jíj hebt er nooit iets voor hoeven te doen. Daarom ben je bang dat je ooit te kort zult komen.’ Blind van woede greep hij het eerste het beste voorwerp dat hij pakken kon, een dienblad. De muis kreeg het blad vol tegen zijn lijf en kwakte een eind verder tegen de muur, met ingeslagen kop. Hij keek vreemd uit zijn plotseling zo dode oogjes. Dit spoedige eind had hij niet verwacht. Desondanks leek zijn bek nog grof en brutaal. Als een bruut was hij gestorven. Hij had geen moment tijd gehad ergens spijt van te hebben.

De zwarten, die verbijsterd hadden gezien hoe Kaspar was omgekomen, begonnen angstwekkend te krijsen. Er steeg een woedend gepiep en gehuil op. In een oogwenk ontstond er een paniek die alle muizen aangreep. De angst sloeg om in agressie. Ze gingen elkaar te lijf. Het café bood het aanzien van een groot kluwen vechtende muizen. Een hysterische massa van bijtende en grauwende diertjes die, nu ze eenmaal bloed hadden geroken, zich overgaven aan de wildste verdediging: de aanval. Niets was meer te zien van witte, zwarte of zelfs maar grijze muizen. Het was één golf van moordende diertjes die elkaar naar de keel vlogen. Nu pas zag Bas hoeveel muizen er al die tijd in zijn zaak hadden gewoond. Ze moesten elkaar al lang te veel zijn geweest.

Blind van moordlust vielen de muizen aan op alles wat bewoog, ook de mensen. Vanaf de bar, stoelen en tafels sprongen ze tegen hen op en beten zich vast in hun kleren. Bas sloeg om zich heen om de bloeddorstige diertjes van zich af te houden. Mireille gilde. Van allen was David het minst in paniek. Hij was een meester in ongeregelde toestanden. Een robbertje vechten deed hem altijd deugd. Ongenadig sloeg hij op de bijtende diertjes in.

`Naar buiten’, schreeuwde Albert. `Ze vreten ons op!’

Om zich heen schoppend en slaand, trappend op dode of stervende lijfjes, bereikten ze het deurgat en vluchtten ze de straat op. Alleen Bas bleef achter in zijn café. Hij voelde zich alsof hij koorts had. In zijn kop ging een orkaan van geluid tekeer, waar hij niet tegen bestand was. Voor zijn ogen draaide een kermis rond. Hij greep zich vast aan het zink om niet tussen de vechtende muizen te vallen. Alle begrip was hij kwijt, hij was ver van de wereld. Voelend hoe steeds meer muizen zich aan hem vastbeten zag hij hoe Crazy, gewapend met een eind hout, in het deurgat stond. Crazy schreeuwde, maar Bas hoorde hem niet. Hij zag dat Crazy met de knuppel op het leger muizen insloeg, maar zelf wilde hij zich niet meer verdedigen. Hij viel om. Een golf muizen spoelde over hem heen. Hij zag alles donker worden. Een vreemde warmte maakte zich van hem meester. Niets voelde hij van de tandjes die hem verminkten. Voor zich zag hij alleen de kop van Kaspar, verminkt tegen de wand. Nog rilde Bas van de haat die nog steeds uit de dode ogen van de muizenkoning straalde. Hij voelde dat iemand hem bij zijn kraag greep en meesleurde. Waarom lieten ze hem nu niet liggen? Zo was het toch goed! Vaag zag hij het bleke gezicht van Crazy, langgerekt vertekend, als in een lachspiegel.

Om zich heen schoppend en slaand, trappend op dode of stervende lijfjes, bereikten ze het deurgat en vluchtten ze de straat op. Alleen Bas bleef achter in zijn café. Hij voelde zich alsof hij koorts had. In zijn kop ging een orkaan van geluid tekeer, waar hij niet tegen bestand was. Voor zijn ogen draaide een kermis rond. Hij greep zich vast aan het zink om niet tussen de vechtende muizen te vallen. Alle begrip was hij kwijt, hij was ver van de wereld. Voelend hoe steeds meer muizen zich aan hem vastbeten zag hij hoe Crazy, gewapend met een eind hout, in het deurgat stond. Crazy schreeuwde, maar Bas hoorde hem niet. Hij zag dat Crazy met de knuppel op het leger muizen insloeg, maar zelf wilde hij zich niet meer verdedigen. Hij viel om. Een golf muizen spoelde over hem heen. Hij zag alles donker worden. Een vreemde warmte maakte zich van hem meester. Niets voelde hij van de tandjes die hem verminkten. Voor zich zag hij alleen de kop van Kaspar, verminkt tegen de wand. Nog rilde Bas van de haat die nog steeds uit de dode ogen van de muizenkoning straalde. Hij voelde dat iemand hem bij zijn kraag greep en meesleurde. Waarom lieten ze hem nu niet liggen? Zo was het toch goed! Vaag zag hij het bleke gezicht van Crazy, langgerekt vertekend, als in een lachspiegel.

`Je bloedt als een rund’, riep Crazy. `Kom op, naar buiten.’

Plotseling stormde de troep muizen, als op commando, naar het deurgat. Ze renden elkaar ondersteboven in de deuropening. Zigzaggend ging de horde over de weg. In een opperste vorm van zelfvernietiging zwenkte het hele hysterisch krijsende leger naar de gracht en dook het water in. In een paar tellen was het krijsen verstomd. Het werd vreemd stil.

`We halen een dokter voor je’, zei Crazy terwijl hij Bas op de stoep legde.

`Ik wil hier niet weg’, zei Bas.

`Hier kun je niet meer leven’, zei Crazy. `Je zou je altijd blijven herinneren hoe het ooit is geweest.’

Het was nu doodstil op straat. Mireille en David stonden dicht tegen elkaar. Ze hielden elkaar vast. Dat gaf hun een beetje moed. Ze voelden hoe warm hun huid was. Hoe ze roken naar spek en nat papier.

Ze schrokken van een stel ratten dat triomfantelijk door de goot rende, even stilhield om naar hen te kijken en er dan weer haastig vandoor ging.

`De pest breekt uit’, zei Crazy. `Als de ratten bovenkomen, kondigt dat het bederf aan. Het verval. Ratten hebben daar een neus voor. Ze komen alleen af op rotte troep en kadavers.’

Er lag een vaag schijnsel vlak boven de straat. Het kwam uit de rioolputten. De fosforescerende gloed van rottend afval. Een vreemd geluid klonk op. Druppels vielen op een blikken plaat, dansende diertjes met ijzeren beslag aan de pootjes. Albert kon het geluid niet verdragen. Hij trapte de lekkende goot van de muur. Het geluid bleef weg. De beestjes waren dood. Het was weer stil.

Plotseling zag David de maan, die als een bleek vod aan de hemel stond. Hij pakte de katapult uit zijn zak, richtte naar de maan en schoot. Stukken bleek licht, als repen wit papier, vielen over de stad. Ze waaiden in de goot als oude, vochtige kranten.

EINDE

Ton van Reen: Katapult (27 – slot)

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: - Katapult, de ondergang van Amsterdam, Reen, Ton van

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature