Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

J a n e A u s t e n

(1775 – 1817)

Oh! Mr Best You’re Very Bad

Oh! Mr. Best, you’re very bad

And all the world shall know it;

Your base behaviour shall be sung

By me, a tunefull Poet.–

You used to go to Harrowgate

Each summer as it came,

And why I pray should you refuse

To go this year the same?–

The way’s as plain, the road’s as smooth,

The Posting not increased;

You’re scarcely stouter than you were,

Not younger Sir at least.–

If e’er the waters were of use

Why now their use forego?

You may not live another year,

All’s mortal here below.–

It is your duty Mr Best

To give your health repair.

Vain else your Richard’s pills will be,

And vain your Consort’s care.

But yet a nobler Duty calls

You now towards the North.

Arise ennobled–as Escort

Of Martha Lloyd stand forth.

She wants your aid–she honours you

With a distinguished call.

Stand forth to be the friend of her

Who is the friend of all.–

Take her, and wonder at your luck,

In having such a Trust.

Her converse sensible and sweet

Will banish heat and dust.–

So short she’ll make the journey seem

You’ll bid the Chaise stand still.

T’will be like driving at full speed

From Newb’ry to Speen hill.–

Convey her safe to Morton’s wife

And I’ll forget the past,

And write some verses in your praise

As finely and as fast.

But if you still refuse to go

I’ll never let your rest,

Buy haunt you with reproachful song

Oh! wicked Mr. Best!–

.jpg)

Jane Austen poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

‘Het is geen roman, ‘t is een aanklacht!’

150 jaar Max Havelaar

Tentoonstelling rond het meesterwerk van Multatuli

woensdag 3 februari, 10:00 – zondag 16 mei 2010, 17:00 uur

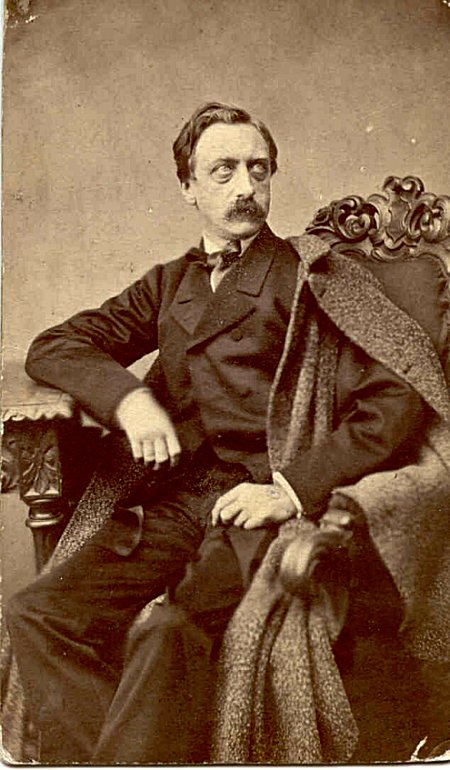

Honderdvijftig jaar geleden schreef Multatuli zijn beroemde boek Max Havelaar: een werk van uitzonderlijke literaire kwaliteit, dat bovendien een enorme maatschappelijke en politieke impact heeft gehad. Het is dan ook opgenomen in de Canon van de Nederlandse Geschiedenis. De uitgave van dit belangrijke boek wordt herdacht met de tentoonstelling ‘Het is geen roman, ‘t is een aanklacht!’ 150 jaar Max Havelaar. Deze tentoonstelling is te zien bij de Bijzondere Collecties van de Universiteit van Amsterdam, de plek waar de handschriften van Multatuli worden bewaard.

Op 15 mei 1860 verscheen bij uitgeverij De Ruyter in Amsterdam het boek dat de Nederlandse geschiedenis een andere wending zou geven: Max Havelaar of de koffij-veilingen van de Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij. Multatuli, pseudoniem van Eduard Douwes Dekker (1820–1887), wilde met het boek de misstanden aan de kaak stellen die hij had meegemaakt toen hij van 1838 tot 1856 als ambtenaar diende in Nederlands-Indië.

.jpg)

Tentoonstelling

In de tentoonstelling wordt het politieke, maatschappelijke en literaire belang van Max Havelaar in beeld gebracht. Centraal staat de aanklacht tegen onderdrukking, een boodschap die nog steeds actueel is. De tentoonstelling is gemaakt door de Bijzondere Collecties van de Universiteit van Amsterdam in samenwerking met het Multatuli Genootschap.

Over Max Havelaar en Multatuli wordt nog steeds veel geschreven en gesproken. De aanklacht tegen onderdrukking en strijd voor rechtvaardige en eerlijke handel (fair trade) is een boodschap die nog altijd actueel is. Het internationale keurmerk voor fair trade-producten heet in een aantal Europese landen dan ook Max Havelaar. Ook hiervoor aandacht in de tentoonstelling.

Multatuli hekelde in zijn boek de koopman en de dominee, klaagde het koloniale wanbestuur aan en rechtvaardigde de ambtenaar die wel voor de verdrukten opkwam. Na het verschijnen van Max Havelaar kon men niet meer ontkennen dat er in de kolonie veel mis was. Het boek had een sturende werking, zowel voor het ambtelijke apparaat in Nederlands-Indië als voor de koloniale politiek, en veranderde definitief het denken over het kolonialisme in Nederland.

De uitzonderlijke literaire kwaliteit van Max Havelaar is altijd geroemd. Met recht geldt Multatuli als een van de belangrijkste schrijvers uit onze literatuur. Maar het was hem niet te doen om de kunst, hij wilde vooral de publieke opinie beïnvloeden. Hoewel hij zijn boodschap verpakte als roman, was het een vlijmscherpe politieke satire.

‘Het is geen roman, ‘t is een aanklacht!’

Op 13 oktober 1859 schreef Multatuli aan zijn vrouw Tine: ‘Lieve hart, mijn boek is af, mijn boek is af! Hoe vind je dat? (…) Het zal als een donderslag in het land vallen dat beloof ik je.’ En aan tekstbezorger Jacob van Lennep, die met zijn ingrepen de angel uit het boek haalde, liet hij weten: ‘(…) het is geen roman. ‘t Is eene geschiedenis. ‘t Is eene memorie van grieven, ‘t Is eene aanklagt, ‘t Is eene sommatie!’

Max Havelaar Academie

Ter gelegenheid van 150 jaar Max Havelaar hebben de Bijzondere Collecties de Max Havelaar Academie opgericht. Zes studenten krijgen de gelegenheid om als stage, tussen januari en mei 2010, een ‘nieuwe Max Havelaar’ te maken. De stageopdracht luidt: ‘Verplaats de thema’s uit de Max Havelaar naar de 21ste eeuw en maak nieuwe verhalen, met moderne (geschreven en audiovisuele) media, die eenzelfde effect willen hebben als het oorspronkelijke boek heeft gehad.’ Een serie publiekslezingen/’masterclasses’ over de actuele betekenis van het boek is onderdeel van de Max Havelaar Academie.

Het is geen roman, ‘t is een aanklacht! 150 jaar Max Havelaar

3 februari t/m 16 mei 2010

Bijzondere Collecties van de Universiteit van Amsterdam

Oude Turfmarkt 129 (Rokin) – 1012 GC Amsterdam

open di–vrij 10–17 uur, za–zo 13–17 uur

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli, Multatuli

.jpg)

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Little Cloud

Eight years before he had seen his friend off at the North Wall and wished him godspeed. Gallaher had got on. You could tell that at once by his travelled air, his well-cut tweed suit, and fearless accent. Few fellows had talents like his and fewer still could remain unspoiled by such success. Gallaher’s heart was in the right place and he had deserved to win. It was something to have a friend like that.

Little Chandler’s thoughts ever since lunch-time had been of his meeting with Gallaher, of Gallaher’s invitation and of the great city London where Gallaher lived. He was called Little Chandler because, though he was but slightly under the average stature, he gave one the idea of being a little man. His hands were white and small, his frame was fragile, his voice was quiet and his manners were refined. He took the greatest care of his fair silken hair and moustache and used perfume discreetly on his handkerchief. The half-moons of his nails were perfect and when he smiled you caught a glimpse of a row of childish white teeth.

As he sat at his desk in the King’s Inns he thought what changes those eight years had brought. The friend whom he had known under a shabby and necessitous guise had become a brilliant figure on the London Press. He turned often from his tiresome writing to gaze out of the office window. The glow of a late autumn sunset covered the grass plots and walks. It cast a shower of kindly golden dust on the untidy nurses and decrepit old men who drowsed on the benches; it flickered upon all the moving figures, on the children who ran screaming along the gravel paths and on everyone who passed through the gardens. He watched the scene and thought of life; and (as always happened when he thought of life) he became sad. A gentle melancholy took possession of him. He felt how useless it was to struggle against fortune, this being the burden of wisdom which the ages had bequeathed to him.

He remembered the books of poetry upon his shelves at home. He had bought them in his bachelor days and many an evening, as he sat in the little room off the hall, he had been tempted to take one down from the bookshelf and read out something to his wife. But shyness had always held him back; and so the books had remained on their shelves. At times he repeated lines to himself and this consoled him.

When his hour had struck he stood up and took leave of his desk and of his fellow-clerks punctiliously. He emerged from under the feudal arch of the King’s Inns, a neat modest figure, and walked swiftly down Henrietta Street. The golden sunset was waning and the air had grown sharp. A horde of grimy children populated the street. They stood or ran in the roadway or crawled up the steps before the gaping doors or squatted like mice upon the thresholds. Little Chandler gave them no thought. He picked his way deftly through all that minute vermin-like life and under the shadow of the gaunt spectral mansions in which the old nobility of Dublin had roystered. No memory of the past touched him, for his mind was full of a present joy.

He had never been in Corless’s but he knew the value of the name. He knew that people went there after the theatre to eat oysters and drink liqueurs; and he had heard that the waiters there spoke French and German. Walking swiftly by at night he had seen cabs drawn up before the door and richly dressed ladies, escorted by cavaliers, alight and enter quickly. They wore noisy dresses and many wraps. Their faces were powdered and they caught up their dresses, when they touched earth, like alarmed Atalantas. He had always passed without turning his head to look. It was his habit to walk swiftly in the street even by day and whenever he found himself in the city late at night he hurried on his way apprehensively and excitedly. Sometimes, however, he courted the causes of his fear. He chose the darkest and narrowest streets and, as he walked boldly forward, the silence that was spread about his footsteps troubled him, the wandering, silent figures troubled him; and at times a sound of low fugitive laughter made him tremble like a leaf.

He turned to the right towards Capel Street. Ignatius Gallaher on the London Press! Who would have thought it possible eight years before? Still, now that he reviewed the past, Little Chandler could remember many signs of future greatness in his friend. People used to say that Ignatius Gallaher was wild Of course, he did mix with a rakish set of fellows at that time. drank freely and borrowed money on all sides. In the end he had got mixed up in some shady affair, some money transaction: at least, that was one version of his flight. But nobody denied him talent. There was always a certain . . . something in Ignatius Gallaher that impressed you in spite of yourself. Even when he was out at elbows and at his wits’ end for money he kept up a bold face. Little Chandler remembered (and the remembrance brought a slight flush of pride to his cheek) one of Ignatius Gallaher’s sayings when he was in a tight corner:

“Half time now, boys,” he used to say light-heartedly. “Where’s my considering cap?”

That was Ignatius Gallaher all out; and, damn it, you couldn’t but admire him for it.

Little Chandler quickened his pace. For the first time in his life he felt himself superior to the people he passed. For the first time his soul revolted against the dull inelegance of Capel Street. There was no doubt about it: if you wanted to succeed you had to go away. You could do nothing in Dublin. As he crossed Grattan Bridge he looked down the river towards the lower quays and pitied the poor stunted houses. They seemed to him a band of tramps, huddled together along the riverbanks, their old coats covered with dust and soot, stupefied by the panorama of sunset and waiting for the first chill of night bid them arise, shake themselves and begone. He wondered whether he could write a poem to express his idea. Perhaps Gallaher might be able to get it into some London paper for him. Could he write something original? He was not sure what idea he wished to express but the thought that a poetic moment had touched him took life within him like an infant hope. He stepped onward bravely.

Every step brought him nearer to London, farther from his own sober inartistic life. A light began to tremble on the horizon of his mind. He was not so old, thirty-two. His temperament might be said to be just at the point of maturity. There were so many different moods and impressions that he wished to express in verse. He felt them within him. He tried weigh his soul to see if it was a poet’s soul. Melancholy was the dominant note of his temperament, he thought, but it was a melancholy tempered by recurrences of faith and resignation and simple joy. If he could give expression to it in a book of poems perhaps men would listen. He would never be popular: he saw that. He could not sway the crowd but he might appeal to a little circle of kindred minds. The English critics, perhaps, would recognise him as one of the Celtic school by reason of the melancholy tone of his poems; besides that, he would put in allusions. He began to invent sentences and phrases from the notice which his book would get. “Mr. Chandler has the gift of easy and graceful verse.” . . . “wistful sadness pervades these poems.” . . . “The Celtic note.” It was a pity his name was not more Irish-looking. Perhaps it would be better to insert his mother’s name before the surname: Thomas Malone Chandler, or better still: T. Malone Chandler. He would speak to Gallaher about it.

He pursued his revery so ardently that he passed his street and had to turn back. As he came near Corless’s his former agitation began to overmaster him and he halted before the door in indecision. Finally he opened the door and entered.

The light and noise of the bar held him at the doorways for a few moments. He looked about him, but his sight was confused by the shining of many red and green wine-glasses The bar seemed to him to be full of people and he felt that the people were observing him curiously. He glanced quickly to right and left (frowning slightly to make his errand appear serious), but when his sight cleared a little he saw that nobody had turned to look at him: and there, sure enough, was Ignatius Gallaher leaning with his back against the counter and his feet planted far apart.

“Hallo, Tommy, old hero, here you are! What is it to be? What will you have? I’m taking whisky: better stuff than we get across the water. Soda? Lithia? No mineral? I’m the same Spoils the flavour. . . . Here, garçon, bring us two halves of malt whisky, like a good fellow. . . . Well, and how have you been pulling along since I saw you last? Dear God, how old we’re getting! Do you see any signs of aging in me, eh, what? A little grey and thin on the top, what?”

Ignatius Gallaher took off his hat and displayed a large closely cropped head. His face was heavy, pale and cleanshaven. His eyes, which were of bluish slate-colour, relieved his unhealthy pallor and shone out plainly above the vivid orange tie he wore. Between these rival features the lips appeared very long and shapeless and colourless. He bent his head and felt with two sympathetic fingers the thin hair at the crown. Little Chandler shook his head as a denial. Ignatius Galaher put on his hat again.

“It pulls you down,” be said, “Press life. Always hurry and scurry, looking for copy and sometimes not finding it: and then, always to have something new in your stuff. Damn proofs and printers, I say, for a few days. I’m deuced glad, I can tell you, to get back to the old country. Does a fellow good, a bit of a holiday. I feel a ton better since I landed again in dear dirty Dublin. . . . Here you are, Tommy. Water? Say when.”

Little Chandler allowed his whisky to be very much diluted.

“You don’t know what’s good for you, my boy,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I drink mine neat.”

“I drink very little as a rule,” said Little Chandler modestly. “An odd half-one or so when I meet any of the old crowd: that’s all.”

“Ah well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, cheerfully, “here’s to us and to old times and old acquaintance.”

They clinked glasses and drank the toast.

“I met some of the old gang today,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “O’Hara seems to be in a bad way. What’s he doing?”

“Nothing,” said Little Chandler. “He’s gone to the dogs.”

“But Hogan has a good sit, hasn’t he?”

“Yes; he’s in the Land Commission.”

“I met him one night in London and he seemed to be very flush. . . . Poor O’Hara! Boose, I suppose?”

“Other things, too,” said Little Chandler shortly.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“Tommy,” he said, “I see you haven’t changed an atom. You’re the very same serious person that used to lecture me on Sunday mornings when I had a sore head and a fur on my tongue. You’d want to knock about a bit in the world. Have you never been anywhere even for a trip?”

“I’ve been to the Isle of Man,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“The Isle of Man!” he said. “Go to London or Paris: Paris, for choice. That’d do you good.”

“Have you seen Paris?”

“I should think I have! I’ve knocked about there a little.”

“And is it really so beautiful as they say?” asked Little Chandler.

He sipped a little of his drink while Ignatius Gallaher finished his boldly.

“Beautiful?” said Ignatius Gallaher, pausing on the word and on the flavour of his drink. “It’s not so beautiful, you know. Of course, it is beautiful. . . . But it’s the life of Paris; that’s the thing. Ah, there’s no city like Paris for gaiety, movement, excitement. . . . ”

Little Chandler finished his whisky and, after some trouble, succeeded in catching the barman’s eye. He ordered the same again.

“I’ve been to the Moulin Rouge,” Ignatius Gallaher continued when the barman had removed their glasses, “and I’ve been to all the Bohemian cafes. Hot stuff! Not for a pious chap like you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler said nothing until the barman returned with two glasses: then he touched his friend’s glass lightly and reciprocated the former toast. He was beginning to feel somewhat disillusioned. Gallaher’s accent and way of expressing himself did not please him. There was something vulgar in his friend which he had not observed before. But perhaps it was only the result of living in London amid the bustle and competition of the Press. The old personal charm was still there under this new gaudy manner. And, after all, Gallaher had lived, he had seen the world. Little Chandler looked at his friend enviously.

“Everything in Paris is gay,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “They believe in enjoying life, and don’t you think they’re right? If you want to enjoy yourself properly you must go to Paris. And, mind you, they’ve a great feeling for the Irish there. When they heard I was from Ireland they were ready to eat me, man.”

Little Chandler took four or five sips from his glass.

“Tell me,” he said, “is it true that Paris is so . . . immoral as they say?”

Ignatius Gallaher made a catholic gesture with his right arm.

“Every place is immoral,” he said. “Of course you do find spicy bits in Paris. Go to one of the students’ balls, for instance. That’s lively, if you like, when the cocottes begin to let themselves loose. You know what they are, I suppose?”

“I’ve heard of them,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher drank off his whisky and shook his had.

“Ah,” he said, “you may say what you like. There’s no woman like the Parisienne, for style, for go.”

“Then it is an immoral city,” said Little Chandler, with timid insistence, “I mean, compared with London or Dublin?”

“London!” said Ignatius Gallaher. “It’s six of one and half-a-dozen of the other. You ask Hogan, my boy. I showed him a bit about London when he was over there. He’d open your eye. . . . I say, Tommy, don’t make punch of that whisky: liquor up.”

“No, really. . . . ”

“O, come on, another one won’t do you any harm. What is it? The same again, I suppose?”

“Well . . . all right.”

“François, the same again. . . . Will you smoke, Tommy?”

Ignatius Gallaher produced his cigar-case. The two friends lit their cigars and puffed at them in silence until their drinks were served.

“I’ll tell you my opinion,” said Ignatius Gallaher, emerging after some time from the clouds of smoke in which he had taken refuge, “it’s a rum world. Talk of immorality! I’ve heard of cases, what am I saying?, I’ve known them: cases of . . . immorality. . . . ”

Ignatius Gallaher puffed thoughtfully at his cigar and then, in a calm historian’s tone, he proceeded to sketch for his friend some pictures of the corruption which was rife abroad. He summarised the vices of many capitals and seemed inclined to award the palm to Berlin. Some things he could not vouch for (his friends had told him), but of others he had had personal experience. He spared neither rank nor caste. He revealed many of the secrets of religious houses on the Continent and described some of the practices which were fashionable in high society and ended by telling, with details, a story about an English duchess, a story which he knew to be true. Little Chandler as astonished.

“Ah, well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “here we are in old jog-along Dublin where nothing is known of such things.”

“How dull you must find it,” said Little Chandler, “after all the other places you’ve seen!”

Well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “it’s a relaxation to come over here, you know. And, after all, it’s the old country, as they say, isn’t it? You can’t help having a certain feeling for it. That’s human nature. . . . But tell me something about yourself. Hogan told me you had . . . tasted the joys of connubial bliss. Two years ago, wasn’t it?”

Little Chandler blushed and smiled.

“Yes,” he said. “I was married last May twelve months.”

“I hope it’s not too late in the day to offer my best wishes,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I didn’t know your address or I’d have done so at the time.”

He extended his hand, which Little Chandler took.

“Well, Tommy,” he said, “I wish you and yours every joy in life, old chap, and tons of money, and may you never die till I shoot you. And that’s the wish of a sincere friend, an old friend. You know that?”

“I know that,” said Little Chandler.

“Any youngsters?” said Ignatius Gallaher.

Little Chandler blushed again.

“We have one child,” he said.

“Son or daughter?”

“A little boy.”

Ignatius Gallaher slapped his friend sonorously on the back.

“Bravo,” he said, “I wouldn’t doubt you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler smiled, looked confusedly at his glass and bit his lower lip with three childishly white front teeth.

“I hope you’ll spend an evening with us,” he said, “before you go back. My wife will be delighted to meet you. We can have a little music and, , ”

“Thanks awfully, old chap,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “I’m sorry we didn’t meet earlier. But I must leave tomorrow night.”

“Tonight, perhaps . . . ?”

“I’m awfully sorry, old man. You see I’m over here with another fellow, clever young chap he is too, and we arranged to go to a little card-party. Only for that . . . ”

“O, in that case . . . ”

“But who knows?” said Ignatius Gallaher considerately. “Next year I may take a little skip over here now that I’ve broken the ice. It’s only a pleasure deferred.”

“Very well,” said Little Chandler, “the next time you come we must have an evening together. That’s agreed now, isn’t it?”

“Yes, that’s agreed,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “Next year if I come, parole d’honneur.”

“And to clinch the bargain,” said Little Chandler, “we’ll just have one more now.”

Ignatius Gallaher took out a large gold watch and looked a it.

“Is it to be the last?” he said. “Because you know, I have an a.p.”

“O, yes, positively,” said Little Chandler.

“Very well, then,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “let us have another one as a deoc an doruis, that’s good vernacular for a small whisky, I believe.”

Little Chandler ordered the drinks. The blush which had risen to his face a few moments before was establishing itself. A trifle made him blush at any time: and now he felt warm and excited. Three small whiskies had gone to his head and Gallaher’s strong cigar had confused his mind, for he was a delicate and abstinent person. The adventure of meeting Gallaher after eight years, of finding himself with Gallaher in Corless’s surrounded by lights and noise, of listening to Gallaher’s stories and of sharing for a brief space Gallaher’s vagrant and triumphant life, upset the equipoise of his sensitive nature. He felt acutely the contrast between his own life and his friend’s and it seemed to him unjust. Gallaher was his inferior in birth and education. He was sure that he could do something better than his friend had ever done, or could ever do, something higher than mere tawdry journalism if he only got the chance. What was it that stood in his way? His unfortunate timidity He wished to vindicate himself in some way, to assert his manhood. He saw behind Gallaher’s refusal of his invitation. Gallaher was only patronising him by his friendliness just as he was patronising Ireland by his visit.

The barman brought their drinks. Little Chandler pushed one glass towards his friend and took up the other boldly.

“Who knows?” he said, as they lifted their glasses. “When you come next year I may have the pleasure of wishing long life and happiness to Mr. and Mrs. Ignatius Gallaher.”

Ignatius Gallaher in the act of drinking closed one eye expressively over the rim of his glass. When he had drunk he smacked his lips decisively, set down his glass and said:

“No blooming fear of that, my boy. I’m going to have my fling first and see a bit of life and the world before I put my head in the sack, if I ever do.”

“Some day you will,” said Little Chandler calmly.

Ignatius Gallaher turned his orange tie and slate-blue eyes full upon his friend.

“You think so?” he said.

“You’ll put your head in the sack,” repeated Little Chandler stoutly, “like everyone else if you can find the girl.”

He had slightly emphasised his tone and he was aware that he had betrayed himself; but, though the colour had heightened in his cheek, he did not flinch from his friend’s gaze. Ignatius Gallaher watched him for a few moments and then said:

“If ever it occurs, you may bet your bottom dollar there’ll be no mooning and spooning about it. I mean to marry money. She’ll have a good fat account at the bank or she won’t do for me.”

Little Chandler shook his head.

“Why, man alive,” said Ignatius Gallaher, vehemently, “do you know what it is? I’ve only to say the word and tomorrow I can have the woman and the cash. You don’t believe it? Well, I know it. There are hundreds, what am I saying?, thousands of rich Germans and Jews, rotten with money, that’d only be too glad. . . . You wait a while my boy. See if I don’t play my cards properly. When I go about a thing I mean business, I tell you. You just wait.”

He tossed his glass to his mouth, finished his drink and laughed loudly. Then he looked thoughtfully before him and said in a calmer tone:

“But I’m in no hurry. They can wait. I don’t fancy tying myself up to one woman, you know.”

He imitated with his mouth the act of tasting and made a wry face.

“Must get a bit stale, I should think,” he said.

Little Chandler sat in the room off the hall, holding a child in his arms. To save money they kept no servant but Annie’s young sister Monica came for an hour or so in the morning and an hour or so in the evening to help. But Monica had gone home long ago. It was a quarter to nine. Little Chandler had come home late for tea and, moreover, he had forgotten to bring Annie home the parcel of coffee from Bewley’s. Of course she was in a bad humour and gave him short answers. She said she would do without any tea but when it came near the time at which the shop at the corner closed she decided to go out herself for a quarter of a pound of tea and two pounds of sugar. She put the sleeping child deftly in his arms and said:

“Here. Don’t waken him.”

A little lamp with a white china shade stood upon the table and its light fell over a photograph which was enclosed in a frame of crumpled horn. It was Annie’s photograph. Little Chandler looked at it, pausing at the thin tight lips. She wore the pale blue summer blouse which he had brought her home as a present one Saturday. It had cost him ten and elevenpence; but what an agony of nervousness it had cost him! How he had suffered that day, waiting at the shop door until the shop was empty, standing at the counter and trying to appear at his ease while the girl piled ladies’ blouses before him, paying at the desk and forgetting to take up the odd penny of his change, being called back by the cashier, and finally, striving to hide his blushes as he left the shop by examining the parcel to see if it was securely tied. When he brought the blouse home Annie kissed him and said it was very pretty and stylish; but when she heard the price she threw the blouse on the table and said it was a regular swindle to charge ten and elevenpence for it. At first she wanted to take it back but when she tried it on she was delighted with it, especially with the make of the sleeves, and kissed him and said he was very good to think of her.

Hm! . . .

He looked coldly into the eyes of the photograph and they answered coldly. Certainly they were pretty and the face itself was pretty. But he found something mean in it. Why was it so unconscious and ladylike? The composure of the eyes irritated him. They repelled him and defied him: there was no passion in them, no rapture. He thought of what Gallaher had said about rich Jewesses. Those dark Oriental eyes, he thought, how full they are of passion, of voluptuous longing! . . . Why had he married the eyes in the photograph?

He caught himself up at the question and glanced nervously round the room. He found something mean in the pretty furniture which he had bought for his house on the hire system. Annie had chosen it herself and it reminded him of her. It too was prim and pretty. A dull resentment against his life awoke within him. Could he not escape from his little house? Was it too late for him to try to live bravely like Gallaher? Could he go to London? There was the furniture still to be paid for. If he could only write a book and get it published, that might open the way for him.

A volume of Byron’s poems lay before him on the table. He opened it cautiously with his left hand lest he should waken the child and began to read the first poem in the book:

Hushed are the winds and still the evening gloom,

Not e’en a Zephyr wanders through the grove,

Whilst I return to view my Margaret’s tomb

And scatter flowers on the dust I love.

He paused. He felt the rhythm of the verse about him in the room. How melancholy it was! Could he, too, write like that, express the melancholy of his soul in verse? There were so many things he wanted to describe: his sensation of a few hours before on Grattan Bridge, for example. If he could get back again into that mood. . . .

The child awoke and began to cry. He turned from the page and tried to hush it: but it would not be hushed. He began to rock it to and fro in his arms but its wailing cry grew keener. He rocked it faster while his eyes began to read the second stanza:

Within this narrow cell reclines her clay,

That clay where once . . .

It was useless. He couldn’t read. He couldn’t do anything. The wailing of the child pierced the drum of his ear. It was useless, useless! He was a prisoner for life. His arms trembled with anger and suddenly bending to the child’s face he shouted:

“Stop!”

The child stopped for an instant, had a spasm of fright and began to scream. He jumped up from his chair and walked hastily up and down the room with the child in his arms. It began to sob piteously, losing its breath for four or five seconds, and then bursting out anew. The thin walls of the room echoed the sound. He tried to soothe it but it sobbed more convulsively. He looked at the contracted and quivering face of the child and began to be alarmed. He counted seven sobs without a break between them and caught the child to his breast in fright. If it died! . . .

The door was burst open and a young woman ran in, panting.

“What is it? What is it?” she cried.

The child, hearing its mother’s voice, broke out into a paroxysm of sobbing.

“It’s nothing, Annie . . . it’s nothing. . . . He began to cry . . . ”

She flung her parcels on the floor and snatched the child from him.

“What have you done to him?” she cried, glaring into his face.

Little Chandler sustained for one moment the gaze of her eyes and his heart closed together as he met the hatred in them. He began to stammer:

“It’s nothing. . . . He . . . he began to cry. . . . I couldn’t . . . I didn’t do anything. . . . What?”

Giving no heed to him she began to walk up and down the room, clasping the child tightly in her arms and murmuring:

“My little man! My little mannie! Was ’ou frightened, love? . . . There now, love! There now!… Lambabaun! Mamma’s little lamb of the world! . . . There now!”

Little Chandler felt his cheeks suffused with shame and he stood back out of the lamplight. He listened while the paroxysm of the child’s sobbing grew less and less; and tears of remorse started to his eyes.

.jpg)

James Joyce: A Little Cloud

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

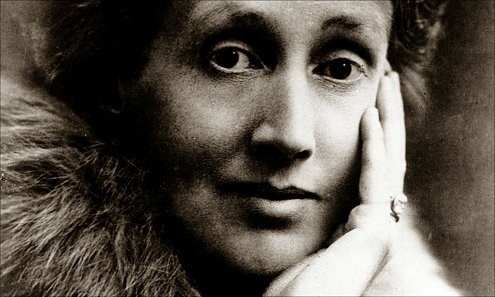

V i r g i n i a W o o l f

(1882-1941)

Monday Or Tuesday

Lazy and indifferent, shaking space easily from his wings, knowing his way, the heron passes over the church beneath the sky. White and distant, absorbed in itself, endlessly the sky covers and uncovers, moves and remains. A lake? Blot the shores of it out! A mountain? Oh, perfect the sun gold on its slopes. Down that falls. Ferns then, or white feathers, for ever and ever.

Desiring truth, awaiting it, laboriously distilling a few words, for ever desiring (a cry starts to the left, another to the right. Wheels strike divergently. Omnibuses conglomerate in conflict) for ever desiring (the clock asseverates with twelve distinct strokes that it is mid-day; light sheds gold scales; children swarm) for ever desiring truth. Red is the dome; coins hang on the trees; smoke trails from the chimneys; bark, shout, cry “Iron for sale” and truth?

Radiating to a point men’s feet and women’s feet, black or gold-encrusted (This foggy weather. Sugar? No, thank you. The commonwealth of the future) the firelight darting and making the room red, save for the black figures and their bright eyes, while outside a van discharges, Miss Thingummy drinks tea at her desk, and plate-glass preserves fur coats.

Flaunted, leaf-light, drifting at corners, blown across the wheels, silver-splashed, home or not home, gathered, scattered, squandered in separate scales, swept up, down, torn, sunk, assembled and truth?

Now to recollect by the fireside on the white square of marble. From ivory depths words rising shed their blackness, blossom and penetrate. Fallen the book; in the flame, in the smoke, in the momentary sparks or now voyaging, the marble square pendant, minarets beneath and the Indian seas, while space rushes blue and stars glint truth? or now, content with closeness?

Lazy and indifferent the heron returns; the sky veils her stars; then bares them.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: Monday Or Tuesday

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

.jpg)

Wunsch, Indianer zu werden

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Wenn man doch ein Indianer wäre, gleich bereit, und auf dem rennenden Pferde, schief in der Luft, immer wieder kurz erzitterte über dem zitternden Boden, bis man die Sporen ließ, denn es gab keine Sporen, bis man die Zügel wegwarf, denn es gab keine Zügel, und kaum das Land vor sich als glatt gemähte Heide sah, schon ohne Pferdehals und Pferdekopf.

.jpg)

Franz Kafka: Betrachtung 1913 – Für M.B.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

An Unwritten Novel

Such an expression of unhappiness was enough by itself to make one’s eyes slide above the paper’s edge to the poor woman’s face insignificant without that look, almost a symbol of human destiny with it. Life’s what you see in people’s eyes; life’s what they learn, and, having learnt it, never, though they seek to hide it, cease to be aware of what? That life’s like that, it seems. Five faces opposite five mature faces and the knowledge in each face. Strange, though, how people want to conceal it! Marks of reticence are on all those faces: lips shut, eyes shaded, each one of the five doing something to hide or stultify his knowledge. One smokes; another reads; a third checks entries in a pocket book; a fourth stares at the map of the line framed opposite; and the fifththe terrible thing about the fifth is that she does nothing at all. She looks at life. Ah, but my poor, unfortunate woman, do play the game do, for all our sakes, conceal it!

As if she heard me, she looked up, shifted slightly in her seat and sighed. She seemed to apologise and at the same time to say to me, “If only you knew!” Then she looked at life again. “But I do know,” I answered silently, glancing at the Times for manners’ sake. “I know the whole business. ‘Peace between Germany and the Allied Powers was yesterday officially ushered in at Paris Signor Nitti, the Italian Prime Minister a passenger train at Doncaster was in collision with a goods train…’ We all know the Times knows but we pretend we don’t.” My eyes had once more crept over the paper’s rim. She shuddered, twitched her arm queerly to the middle of her back and shook her head. Again I dipped into my great reservoir of life. “Take what you like,” I continued, “births, death, marriages, Court Circular, the habits of birds, Leonardo da Vinci, the Sandhills murder, high wages and the cost of living oh, take what you like,” I repeated, “it’s all in the Times!” Again with infinite weariness she moved her head from side to side until, like a top exhausted with spinning, it settled on her neck.

The Times was no protection against such sorrow as hers. But other human beings forbade intercourse. The best thing to do against life was to fold the paper so that it made a perfect square, crisp, thick, impervious even to life. This done, I glanced up quickly, armed with a shield of my own. She pierced through my shield; she gazed into my eyes as if searching any sediment of courage at the depths of them and damping it to clay. Her twitch alone denied all hope, discounted all illusion.

So we rattled through Surrey and across the border into Sussex. But with my eyes upon life I did not see that the other travellers had left, one by one, till, save for the man who read, we were alone together. Here was Three Bridges station. We drew slowly down the platform and stopped. Was he going to leave us? I prayed both ways I prayed last that he might stay. At that instant he roused himself, crumpled his paper contemptuously, like a thing done with, burst open the door, and left us alone.

The unhappy woman, leaning a little forward, palely and colourlessly addressed me talked of stations and holidays, of brothers at Eastbourne, and the time of the year, which was, I forget now, early or late. But at last looking from the window and seeing, I knew, only life, she breathed, “Staying away hat’s the drawback of it” Ah, now we approached the catastrophe, “My sister-in-law” the bitterness of her tone was like lemon on cold steel, and speaking, not to me, but to herself, she muttered, “nonsense, she would say that’s what they all say,” and while she spoke she fidgeted as though the skin on her back were as a plucked fowl’s in a poulterer’s shop-window.

“Oh, that cow!” she broke off nervously, as though the great wooden cow in the meadow had shocked her and saved her from some indiscretion. Then she shuddered, and then she made the awkward, angular movement that I had seen before, as if, after the spasm, some spot between the shoulders burnt or itched. Then again she looked the most unhappy woman in the world, and I once more reproached her, though not with the same conviction, for if there were a reason, and if I knew the reason, the stigma was removed from life.

“Sisters-in-law,” I said

Her lips pursed as if to spit venom at the word; pursed they remained. All she did was to take her glove and rub hard at a spot on the window-pane. She rubbed as if she would rub something out for ever some stain, some indelible contamination. Indeed, the spot remained for all her rubbing, and back she sank with the shudder and the clutch of the arm I had come to expect. Something impelled me to take my glove and rub my window. There, too, was a little speck on the glass. For all my rubbing, it remained. And then the spasm went through me; I crooked my arm and plucked at the middle of my back. My skin, too, felt like the damp chicken’s skin in the poulterer’s shop-window; one spot between the shoulders itched and irritated, felt clammy, felt raw. Could I reach it? Surreptitiously I tried. She saw me. A smile of infinite irony, infinite sorrow, flitted and faded from her face. But she had communicated, shared her secret, passed her poison; she would speak no more. Leaning back in my corner, shielding my eyes from her eyes, seeing only the slopes and hollows, greys and purples, of the winter’s landscape, I read her message, deciphered her secret, reading it beneath her gaze.

Hilda’s the sister-in-law. Hilda? Hilda? Hilda Marsh Hilda the blooming, the full bosomed, the matronly. Hilda stands at the door as the cab draws up, holding a coin. “Poor Minnie, more of a grasshopper than ever old cloak she had last year. Well, well, with two children these days one can’t do more. No, Minnie, I’ve got it; here you are, cabby none of your ways with me. Come in, Minnie. Oh, I could carry you, let alone your basket!” So they go into the dining-room. “Aunt Minnie, children.”

Slowly the knives and forks sink from the upright. Down they get (Bob and Barbara), hold out hands stiffly; back again to their chairs, staring between the resumed mouthfuls. [But this we’ll skip; ornaments, curtains, trefoil china plate, yellow oblongs of cheese, white squares of biscuit skip oh, but wait! Half-way through luncheon one of those shivers; Bob stares at her, spoon in mouth. “Get on with your pudding, Bob;” but Hilda disapproves. “Why should she twitch?” Skip, skip, till we reach the landing on the upper floor; stairs brass-bound; linoleum worn; oh, yes! little bedroom looking out over the roofs of Eastbourne zigzagging roofs like the spines of caterpillars, this way, that way, striped red and yellow, with blue-black slating]. Now, Minnie, the door’s shut; Hilda heavily descends to the basement; you unstrap the straps of your basket, lay on the bed a meagre nightgown, stand side by side furred felt slippers. The looking-glass no, you avoid the looking-glass. Some methodical disposition of hat-pins. Perhaps the shell box has something in it? You shake it; it’s the pearl stud there was last year that’s all. And then the sniff, the sigh, the sitting by the window. Three o’clock on a December afternoon; the rain drizzling; one light low in the skylight of a drapery emporium; another high in a servant’s bedroom this one goes out. That gives her nothing to look at. A moment’s blankness then, what are you thinking? (Let me peep across at her opposite; she’s asleep or pretending it; so what would she think about sitting at the window at three o’clock in the afternoon? Health, money, hills, her God?) Yes, sitting on the very edge of the chair looking over the roofs of Eastbourne, Minnie Marsh prays to God. That’s all very well; and she may rub the pane too, as though to see God better; but what God does she see? Who’s the God of Minnie Marsh, the God of the back streets of Eastbourne, the God of three o’clock in the afternoon? I, too, see roofs, I see sky; but, oh, dear this seeing of Gods! More like President Kruger than Prince Albert that’s the best I can do for him; and I see him on a chair, in a black frock-coat, not so very high up either; I can manage a cloud or two for him to sit on; and then his hand trailing in the clouds holds a rod, a truncheon is it? black, thick, horned a brutal old bully Minnie’s God! Did he send the itch and the patch and the twitch? Is that why she prays? What she rubs on the window is the stain of sin. Oh, she committed some crime!

I have my choice of crimes. The woods flit and fly in summer there are bluebells; in the opening there, when Spring comes, primroses. A parting, was it, twenty years ago? Vows broken? Not Minnie’s!…She was faithful. How she nursed her mother! All her savings on the tombstone wreaths under glass daffodils in jars. But I’m off the track. A crime…They would say she kept her sorrow, suppressed her secret her sex, they’d say the scientific people. But what flummery to saddle her with sex! No more like this. Passing down the streets of Croyden twenty years ago, the violet loops of ribbon in the draper’s window spangled in the electric light catch her eye. She lingers past six. Still by running she can reach home. She pushes through the glass swing door. It’s sale-time. Shallow trays brim with ribbons. She pauses, pulls this, fingers that with the raised roses on it no need to choose, no need to buy, and each tray with its surprises. “We don’t shut till seven,” and then it is seven. She runs, she rushes, home she reaches, but too late. Neighbours the doctor baby brother the kettle scalded hospital dead or only the shock of it, the blame? Ah, but the detail matters nothing! It’s what she carries with her; the spot, the crime, the thing to expiate, always there between her shoulders. “Yes,” she seems to nod to me, “it’s the thing I did.”

Whether you did, or what you did, I don’t mind; it’s not the thing I want. The draper’s window looped with violet that’ll do; a little cheap perhaps, a little commonplace since one has a choice of crimes, but then so many (let me peep across again still sleeping, or pretending to sleep! white, worn, the mouth closed a touch of obstinacy, more than one would thin no hint of sex) so many crimes aren’t your crime; your crime was cheap; only the retribution solemn; for now the church door opens, the hard wooden pew receives her; on the brown tiles she kneels; every day, winter, summer, dusk, dawn (here she’s at it) prays. All her sins fall, fall, for ever fall. The spot receives them. It’s raised, it’s red, it’s burning. Next she twitches. Small boys point. “Bob at lunch to-day” But elderly women are the worst.

Indeed now you can’t sit praying any longer. Kruger’s sunk beneath the cloud washed over as with a painter’s brush of liquid grey, to which he adds a tinge of black even the tip of the truncheon gone now. That’s what always happens! Just as you’ve seen him, felt him, someone interrupts. It’s Hilda now.

How you hate her! She’ll even lock the bathroom door overnight, too, though it’s only cold water you want, and sometimes when the night’s been bad it seems as if washing helped. And John at breakfast the children meals are worst, and sometimes there are friends ferns don’t altogether hide ’em they guess, too; so out you go along the front, where the waves are grey, and the papers blow, and the glass shelters green and draughty, and the chairs cost tuppence too much for there must be preachers along the sands. Ah, that’s a nigger that’s a funny man that’s a man with parakeets poor little creatures! Is there no one here who thinks of God? just up there, over the pier, with his rod but no here’s nothing but grey in the sky or if it’s blue the white clouds hide him, and the music it’s military music and what are they fishing for? Do they catch them? How the children stare! Well, then home a back way”Home a back way!” The words have meaning; might have been spoken by the old man with whisker no, no, he didn’t really speak; but everything has meaning placards leaning against doorways names above shop-windows red fruit in baskets women’s heads in the hairdresser’ all say “Minnie Marsh!” But here’s a jerk. “Eggs are cheaper!” That’s what always happens! I was heading her over the waterfall, straight for madness, when, like a flock of dream sheep, she turns t’other way and runs between my fingers. Eggs are cheaper. Tethered to the shores of the world, none of the crimes, sorrows, rhapsodies, or insanities for poor Minnie Marsh; never late for luncheon; never caught in a storm without a mackintosh; never utterly unconscious of the cheapness of eggs. So she reaches home rapes her boots.

Have I read you right? But the human face the human face at the top of the fullest sheet of print holds more, withholds more. Now, eyes open, she looks out; and in the human eye how d’you define it? there’s a break a division so that when you’ve grasped the stem the butterfly’s off the moth that hangs in the evening over the yellow flower move, raise your hand, off, high, away. I won’t raise my hand. Hang still, then, quiver, life, soul, spirit, whatever you are of Minnie Marsh I, too, on my flower the hawk over the down alone, or what were the worth of life? To rise; hang still in the evening, in the midday; hang still over the down. The flicker of a hand off, up! then poised again. Alone, unseen; seeing all so still down there, all so lovely. None seeing, none caring. The eyes of others our prisons; their thoughts our cages. Air above, air below. And the moon and immortality…Oh, but I drop to the turf! Are you down too, you in the corner, what’s your name woman Minnie Marsh; some such name as that? There she is, tight to her blossom; opening her hand-bag, from which she takes a hollow shell an egg who was saying that eggs were cheaper? You or I? Oh, it was you who said it on the way home, you remember, when the old gentleman, suddenly opening his umbrella or sneezing was it? Anyhow, Kruger went, and you came “home a back way,” and scraped your boots. Yes. And now you lay across your knees a pocket-handkerchief into which drop little angular fragments of eggshell fragments of a map a puzzle. I wish I could piece them together! If you would only sit still. She’s moved her knees the map’s in bits again. Down the slopes of the Andes the white blocks of marble go bounding and hurtling, crushing to death a whole troop of Spanish muleteers, with their convoy Drake’s booty, gold and silver. But to return

To what, to where? She opened the door, and, putting her umbrella in the stand that goes without saying; so, too, the whiff of beef from the basement; dot, dot, dot. But what I cannot thus eliminate, what I must, head down, eyes shut, with the courage of a battalion and the blindness of a bull, charge and disperse are, indubitably, the figures behind the ferns, commercial travellers. There I’ve hidden them all this time in the hope that somehow they’d disappear, or better still emerge, as indeed they must, if the story’s to go on gathering richness and rotundity, destiny and tragedy, as stories should, rolling along with it two, if not three, commercial travellers and a whole grove of aspidistra. “The fronds of the aspidistra only partly concealed the commercial traveller” Rhododendrons would conceal him utterly, and into the bargain give me my fling of red and white, for which I starve and strive; but rhododendrons in Eastbourne in December on the Marshes’ table no, no, I dare not; it’s all a matter of crusts and cruets, frills and ferns. Perhaps there’ll be a moment later by the sea. Moreover, I feel, pleasantly pricking through the green fretwork and over the glacis of cut glass, a desire to peer and peep at the man opposite one’s as much as I can manage. James Moggridge is it, whom the Marshes call Jimmy? [Minnie, you must promise not to twitch till I’ve got this straight]. James Moggridge travels in shall we say buttons? but the time’s not come for bringing them in the big and the little on the long cards, some peacock-eyed, others dull gold; cairngorms some, and others coral sprays but I say the time’s not come. He travels, and on Thursdays, his Eastbourne day, takes his meals with the Marshes. His red face, his little steady eyes by no means altogether commonplac his enormous appetite (that’s safe; he won’t look at Minnie till the bread’s swamped the gravy dry), napkin tucked diamond-wise but this is primitive, and whatever it may do the reader, don’t take me in. Let’s dodge to the Moggridge household, set that in motion. Well, the family boots are mended on Sundays by James himself. He reads Truth. But his passion? Rose and his wife a retired hospital nurse interesting for God’s sake let me have one woman with a name I like! But no; she’s of the unborn children of the mind, illicit, none the less loved, like my rhododendrons. How many die in every novel that’s written the best, the dearest, while Moggridge lives. It’s life’s fault. Here’s Minnie eating her egg at the moment opposite and at t’other end of the line are we past Lewes? there must be Jimmy or what’s her twitch for?

There must be Moggridge life’s fault. Life imposes her laws; life blocks the way; life’s behind the fern; life’s the tyrant; oh, but not the bully! No, for I assure you I come willingly; I come wooed by Heaven knows what compulsion across ferns and cruets, tables splashed and bottles smeared. I come irresistibly to lodge myself somewhere on the firm flesh, in the robust spine, wherever I can penetrate or find foothold on the person, in the soul, of Moggridge the man. The enormous stability of the fabric; the spine tough as whalebone, straight as oak-tree; the ribs radiating branches; the flesh taut tarpaulin; the red hollows; the suck and regurgitation of the heart; while from above meat falls in brown cubes and beer gushes to be churned to blood again and so we reach the eyes. Behind the aspidistra they see something; black, white, dismal; now the plate again; behind the aspidistra they see elderly woman; “Marsh’s sister, Hilda’s more my sort;” the tablecloth now. “Marsh would know what’s wrong with Morrises…” talk that over; cheese has come; the plate again; turn it round the enormous fingers; now the woman opposite. “Marsh’s sister not a bit like Marsh; wretched, elderly female….You should feed your hens….God’s truth, what’s set her twitching? Not what I said? Dear, dear, dear! These elderly women. Dear, dear!”

[Yes, Minnie; I know you’ve twitched, but one moment James Moggridge].

“Dear, dear, dear!” How beautiful the sound is! like the knock of a mallet on seasoned timber, like the throb of the heart of an ancient whaler when the seas press thick and the green is clouded. “Dear, dear!” what a passing bell for the souls of the fretful to soothe them and solace them, lap them in linen, saying, “So long. Good luck to you!” and then, “What’s your pleasure?” for though Moggridge would pluck his rose for her, that’s done, that’s over. Now what’s the next thing? “Madam, you’ll miss your train,” for they don’t linger.

That’s the man’s way; that’s the sound that reverberates; that’s St. Paul’s and the motor-omnibuses. But we’re brushing the crumbs off. Oh, Moggridge, you won’t stay? You must be off? Are you driving through Eastbourne this afternoon in one of those little carriages? Are you the man who’s walled up in green cardboard boxes, and sometimes has the blinds down, and sometimes sits so solemn staring like a sphinx, and always there’s a look of the sepulchral, something of the undertaker, the coffin, and the dusk about horse and driver? Do tell me but the doors slammed. We shall never meet again. Moggridge, farewell!

Yes, yes, I’m coming. Right up to the top of the house. One moment I’ll linger. How the mud goes round in the mind what a swirl these monsters leave, the waters rocking, the weeds waving and green here, black there, striking to the sand, till by degrees the atoms reassemble, the deposit sifts itself, and again through the eyes one sees clear and still, and there comes to the lips some prayer for the departed, some obsequy for the souls of those one nods to, the people one never meets again.

James Moggridge is dead now, gone for ever. Well, Minnie”I can face it no longer.” If she said that (Let me look at her. She is brushing the eggshell into deep declivities). She said it certainly, leaning against the wall of the bedroom, and plucking at the little balls which edge the claret-coloured curtain. But when the self speaks to the self, who is speaking? the entombed soul, the spirit driven in, in, in to the central catacomb; the self that took the veil and left the world a coward perhaps, yet somehow beautiful, as it flits with its lantern restlessly up and down the dark corridors. “I can bear it no longer,” her spirit says. “That man at lunch Hilda the children.” Oh, heavens, her sob! It’s the spirit wailing its destiny, the spirit driven hither, thither, lodging on the diminishing carpets meagre footholds shrunken shreds of all the vanishing universe love, life, faith, husband, children, I know not what splendours and pageantries glimpsed in girlhood. “Not for me not for me.”

But then the muffins, the bald elderly dog? Bead mats I should fancy and the consolation of underlinen. If Minnie Marsh were run over and taken to hospital, nurses and doctors themselves would exclaim….There’s the vista and the vision there’s the distance the blue blot at the end of the avenue, while, after all, the tea is rich, the muffin hot, and the dog “Benny, to your basket, sir, and see what mother’s brought you!” So, taking the glove with the worn thumb, defying once more the encroaching demon of what’s called going in holes, you renew the fortifications, threading the grey wool, running it in and out.

Running it in and out, across and over, spinning a web through which God himself hush, don’t think of God! How firm the stitches are! You must be proud of your darning. Let nothing disturb her. Let the light fall gently, and the clouds show an inner vest of the first green leaf. Let the sparrow perch on the twig and shake the raindrop hanging to the twig’s elbow…. Why look up? Was it a sound, a thought? Oh, heavens! Back again to the thing you did, the plate glass with the violet loops? But Hilda will come. Ignominies, humiliations, oh! Close the breach.

Having mended her glove, Minnie Marsh lays it in the drawer. She shuts the drawer with decision. I catch sight of her face in the glass. Lips are pursed. Chin held high. Next she laces her shoes. Then she touches her throat. What’s your brooch? Mistletoe or merry-thought? And what is happening? Unless I’m much mistaken, the pulse’s quickened, the moment’s coming, the threads are racing, Niagara’s ahead. Here’s the crisis! Heaven be with you! Down she goes. Courage, courage! Face it, be it! For God’s sake don’t wait on the mat now! There’s the door! I’m on your side. Speak! Confront her, confound her soul!

“Oh, I beg your pardon! Yes, this is Eastbourne. I’ll reach it down for you. Let me try the handle.” [But, Minnie, though we keep up pretences, I’ve read you right I’m with you now].

“That’s all your luggage?”

“Much obliged, I’m sure.”

(But why do you look about you? Hilda won’t come to the station, nor John; and Moggridge is driving at the far side of Eastbourne).

“I’ll wait by my bag, ma’am, that’s safest. He said he’d meet me….Oh, there he is! That’s my son.”

So they walked off together.

Well, but I’m confounded….Surely, Minnie, you know better! A strange young man….Stop! I’ll tell him Minnie! Miss Marsh! I don’t know though. There’s something queer in her cloak as it blows. Oh, but it’s untrue; it’s indecent….Look how he bends as they reach the gateway. She finds her ticket. What’s the joke? Off they go, down the road, side by side….Well, my world’s done for! What do I stand on? What do I know? That’s not Minnie. There never was Moggridge. Who am I? Life’s bare as bone.

And yet the last look of them he stepping from the kerb and she following him round the edge of the big building brims me with wonder floods me anew. Mysterious figures! Mother and son. Who are you? Why do you walk down the street? Where to-night will you sleep, and then, to-morrow? Oh, how it whirls and surges floats me afresh! I start after them. People drive this way and that. The white light splutters and pours. Plate-glass windows. Carnations; chrysanthemums. Ivy in dark gardens. Milk carts at the door. Wherever I go, mysterious figures, I see you, turning the corner, mothers and sons; you, you, you. I hasten, I follow. This, I fancy, must be the sea. Grey is the landscape; dim as ashes; the water murmurs and moves. If I fall on my knees, if I go through the ritual, the ancient antics, it’s you, unknown figures, you I adore; if I open my arms, it’s you I embrace, you I draw to me adorable world!

Virginia Woolf: An unwritten novel

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

.jpg)

Das Gassenfenster

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Wer verlassen lebt und sich doch hie und da irgendwo anschließen möchte, wer mit Rücksicht auf die Veränderungen der Tageszeit, der Witterung, der Berufsverhältnisse und dergleichen ohne weiteres irgend einen beliebigen Arm sehen will, an dem er sich halten könnte, — der wird es ohne ein Gassenfenster nicht lange treiben. Und steht es mit ihm so, daß er gar nichts sucht und nur als müder Mann, die Augen auf und ab zwischen Publikum und Himmel, an seine Fensterbrüstung tritt, und er will nicht und hat ein wenig den Kopf zurückgeneigt, so reißen ihn doch unten die Pferde mit in ihr Gefolge von Wagen und Lärm und damit endlich der menschlichen Eintracht zu.

.jpg)

Franz Kafka: Betrachtung 1913 – Für M.B.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

.jpg)

Zum Nachdenken für Herrenreiter

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Nichts, wenn man es überlegt, kann dazu verlocken, in einem Wettrennen der erste sein zu wollen. Der Ruhm, als der beste Reiter eines Landes anerkannt zu werden, freut beim Losgehn des Orchesters zu stark, als daß sich am Morgen danach die Reue verhindern ließe.

Der Neid der Gegner, listiger, ziemlich einflußreicher Leute, muß uns in dem engen Spalier schmerzen, das wir nun durchreiten nach jener Ebene, die bald vor uns leer war bis auf einige überrundete Reiter, die klein gegen den Rand des Horizonts anritten.

Viele unserer Freunde eilen den Gewinn zu beheben und nur über die Schultern weg schreien sie von den entlegenen Schaltern ihr Hurra zu uns; die besten Freunde aber haben gar nicht auf unser Pferd gesetzt, da sie fürchteten, käme es zum Verluste, müßten sie uns böse sein, nun aber, da unser Pferd das erste war und sie nichts gewonnen haben, drehn sie sich um, wenn wir vorüberkommen und schauen lieber die Tribünen entlang.

Die Konkurrenten rückwärts, fest im Sattel, suchen das Unglück zu überblicken, das sie getroffen hat, und das Unrecht, das ihnen irgendwie zugefügt wird; sie nehmen ein frisches Aussehen an, als müsse ein neues Rennen anfangen und ein ernsthaftes nach diesem Kinderspiel.

Vielen Damen scheint der Sieger lächerlich, weil er sich aufbläht und doch nicht weiß, was anzufangen mit dem ewigen Händeschütteln, Salutieren, Sich-Niederbeugen und In-die-Ferne-Grüßen, während die Besiegten den Mund geschlossen haben und die Hälse ihrer meist wiehernden Pferde leichthin klopfen.

Endlich fängt es gar aus dem trüb gewordenen Himmel zu regnen an.

.jpg)

Franz Kafka: Betrachtung 1913 – Für M.B.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

.jpg)

VROEG IN DE OCHTEND

KOMT ER BLOED UIT DE POMP

door Ton van Reen

‘Opstaan, het is tijd!’

De stem van moeder aan mijn oor, zacht. Ze wil mijn broer die naast me slaapt niet wakker maken. Hij heeft tot lang na middernacht op de boerenveiling asperges gesorteerd, voor een kwartje per uur. We hebben het geld hard nodig. Sinds de dood van vader is het armoe troef. Bij ons vallen de muizen van honger dood van de trap. Als ik op zondag naar de kerk loop, ruik ik het braadvlees van de keukens van het knapzakvolk in de Kerkstraat, dat staat bij die lui al vanaf zaterdagavond te sudderen, zodat op straat iedereen kan ruiken dat ze rijk zijn, maar wij eten op zondag spek. Lekker doorregen spek. Ik lust dat dure vlees dat de kinderen van dat fijne volk moeten eten niet eens. Op dinsdag krijgen we gebakken hersens met zwart brood, en dat is lekker vet. Het ruikt beter dan biefstuk waarvan je, ondanks dat het zo duur is, enge ziektes krijgt. Die knapzakkinderen liggen vaak in het ziekenhuis of ze gaan dood aan tering of typhus of aan de blinde darm, maar wij hebben niet eens een blinde darm. Ons in de Ringovenstraat gebeurt nooit iets. Als je elke dag moet vechten, word je sterk. En door varkenshersens te eten, krijg je er het verstand van de varkens bij, en dat is niet niks. Varkens zijn de meest intelligente dieren. De Amerikaanse soldaten hadden varkens die ze gebruikten als speurhonden, dat zegt mijn grootmoeder, en die waren er op afgericht om Duitsers te ruiken. Dat was niet zo moeilijk, want elke mof die in ons dorp gelegerd is geweest was een angsthaas die al in zijn broek scheet als hij het woord Amerikaan hoorde. Als ik met mijn grootmoeder zit te kaarten, vertelt ze vaak over de Duitsers die de oorlog wilden winnen, maar de soldaten die bij ons ingekwartierd waren, hadden oude geweren met kromme lopen die gevaarlijk waren voor henzelf. De kogels die ze op de Amerikanen afvuurden, kwamen met een boog bij hen terug, als boemerangs. Ricochet-kogels zegt Hartje van Stein, maar waar hij deze wijsheid weer vandaan heeft gehaald? De meeste Duitsers stierven door eigen vuur. Bij ons in het dorp hebben ze zich rot gelachen over die Duitsers die dachten dat ze de wereld de baas waren, maar ze hadden soldaten van tachtig jaar oud. Dat zegt opoe. Die waren zo versleten dat ze de H van Hitler niet uit konden spreken en dan zeiden ze: ‘eil ittele’, dat was om je dood te lachen. Mijn grootmoeder was erbij, jammer dat ik toen nog zo klein was. Als er iets gebeurt, maar hier gebeurt nooit iets, maar toen er echt iets gebeurde, toen was ik er niet bij. Maar ik weet wel alles. Iedereen die hier woont, weet dat Ittele een Italiaans wijf is, die in een café in Meyel de hoer speelt. Nog steeds, ook al heeft ze in de oorlog goed geld verdiend door met hoge Duitse officieren naar bed te gaan. Seyss-Inquart, die hier de Führer was, had op zijn kantoor haar onderbroek naast de Duitse vlag hangen, dat zeggen ze in Meyel. Met de een of andere Feldwebel is ze ook nog getrouwd geweest, dat zeggen ze ook in Meyel, daar weten ze meer van Ittele dan wat zij over zichzelf weet, toen heeft ze zich tijdelijk mevrouw Gräfin von Schaesberg laten noemen, omdat die Feldwebel van adel was. Maar toen de moffen de oorlog verloren hadden, heeft ze Feldwebel Graf von Schaesberg vlug laten vallen. Protestantse turfstekers die in het Noorden van Nederland wonen, maar zelden naar huis gaan omdat het daar zo koud is dat er niet eens kersenbomen groeien, zoeken Ittele op zondag op en gaan met haar naar haar kamertje boven de bar. De gräfin laat zich niet naaien, ze trekt die geile kerels allemaal af, dat weet Hartje van Stein ons te melden, maar op haar beurt naait ze iedereen. Dat zeggen die van Meyel ook. Gek dat die altijd alles zo goed weten, die mummelmondjes van Meyel. Het is net of ze allemaal zonder gebit zijn geboren, of dat ze hele kleine muizentandjes hebben. Het zal wel door inteelt komen. Ittele verdient veel geld, dat zegt Hartje van Stein, die het kan weten omdat zijn moeder ook een hoer is. Maggie noemden de Amerikaanse soldaten haar. Ze pooiert voor de soldaten in de kazerne van Blerick, de Limburgse jagers, die bekend staan als hoerenlopers. Soldaten kunnen beter naar de hoeren gaan dan naar de kerk, zegt Hartje altijd, want tegen een hoer kun je praten en van de kerk krijg je alleen wijwater terug. Hartje is wijs.Veel wijzer dan wij, ook al is hij meer dan een jaar jonger. Wij zijn z’n vriendjes omdat hij zoveel meemaakt, dat maakt hem voor ons interessant.. Bij ons gebeurt nooit wat. Wij werken, eten en slapen, wij zouden net zo goed konijnen kunnen zijn, maar de moeder van Hartje brengt altijd vreemde kerels mee naar huis en dan is het daar nachten lang feest. ‘Geld moet een bestemming hebben,’ dat is ook zo’n gezegde van Hartje. Hij zegt het wel tien keer per dag. Waarom? Omdat zijn moeder alle geld voor zichzelf nodig heeft en hem als een stuk vuil laat rondlopen? Hij eet altijd bij stoker Wismans van de steenfabriek, en die eten daar elke dag bloedworst omdat dat maar een dubbeltje per kilo kost en de uien die ze erbij bakken kosten maar een paar cent.. Een mond meer of minder maakt bij ons niks uit, zegt Wismans, die zelf acht dochters heeft en het spijtig vindt dat hij geen zoon heeft. In Hartje heeft hij een plaatsvervangende zoon, al is het dan maar een hoerenjong. Wie Hartjes vader is? Misschien wel Seyss-Inquart, want Hartje heeft net zo’n smalle kop als die beul die ze in Neurenberg hebben opgehangen. Hartjes moeder geeft alles uit aan whiskey en dure kleren, maar haar huis is een rattenhol. Als er geen vreemde kerels zijn, zit ze in de keuken tussen de rommel te grienen. Soms als we op zoek zijn naar Hartje en binnenlopen, het maakt haar geen moer uit dat we door het hele huis rennen en de blote meiden zien die in de slaapkamer zijn opgeprikt, zit ze maar naar buiten te kijken, en op de vloer rond haar liggen een hoop lege Chief Whip doosjes, ze rookt zich kapot. En flessen whiskey. Als ze ons ziet, maar meestal ziet ze ons niet, of ze doet alsof ze ons niet ziet, roept ze ‘het leven is een avontuur!’ En toch vind ik haar mooi. Ik weet niet waarom, misschien is het de wildheid die uit haar ogen spreekt. Ik zou haar best als moeder willen hebben. Waarom niet? Waarom niet, klootzakken dat jullie zijn, en dat jullie allemaal moeders hebben die zich te barsten werken en die elke dag boven de kookpot met bonte was hangen en die ook nooit naar jullie kijken! Ook al krijg je elke dag brood met reuzel, dat wil nog niet zeggen dat ze van je houden! Ik denk dat Hartjes moeder meer van hem houdt dan de meeste moeders in de Kerkstraat die speelgoed voor hun kinderen kopen en knakworst met witte broodjes op zondagochtend. Ze kopen hun kinderen om. Dat doet Hartjes moeder niet. Ik wil wel in dat kot van haar gaan wonen, dan ruim ik de rotzooi op, dan kan Hartje hier wonen en bij mijn broer slapen en ’s nachts zijn scheten tellen. Als Maggie tegen de avond met de bus naar Blerick gaat, loopt ze kaarsrecht, ook al heeft ze de hele dag gedronken. In haar witte bontjas schrijdt ze naar de bushalte bij de winkel van de Coöperatie en stapt in alsof ze de koningin is. Ze heeft schijt aan al dat volk hier. Net als ik. Jammer dat ze haar geld over de balk gooit. Gräfin Ittele uit Meyel is wijzer. Ze spaart haar geld. Pas heeft ze het huis van de notaris gekocht, dat is een half kasteel, en dat aan de Boerenleenbank verhuurd. Nou heeft ze haar zwarte geld gewit, zeggen de mensen uit Meyel. Wat een klotevolk zeg, dat ze zoveel over anderen te vertellen hebben, terwijl het zelf allemaal stropers en landlopers en daglonders zijn. Peelvolk, net als de Rowwen Heze en Grard Sientje en Klotje Tiktik, die langs de deuren kwam om boterhammen te bedelen, die hij aan elke deur kreeg, zodat hij ’s avonds met een barstende maag in de sloten rolde en zodoende op een kwade dag verzopen is. Omdat mannen vergevingsgezind worden als er ergens goud schittert, zijn er in de Peelrand genoeg kerels te vinden die met Gräfin Ittele willen trouwen. Mijn grootmoeder zegt: altijd: geld dat krom is, maakt recht wat stom is.

Ik had best zes jaar ouder willen zijn, dan had ik de oorlog ook meegemaakt en had ik misschien zelf gezien hoe die dameshoeren met hun Duitse officieren bij Hotel-restaurant Denbach op het terras zaten feest te vieren en grote maaltijden lieten serveren, terwijl de mensen die langs kwamen rammelden van de honger. Jan Horsten, die vaandrig bij de padvinders is en altijd aan ons zit te pullukken, vertelt vaak dat hij gezien heeft dat een granaat die was afgevuurd door de Amerikanen Gefreiter Hermanns van de straat veegde. Sommigen zeggen dat niet de bevrijders die maanden later in tanks het dorp binnenrolden en de hond van Kapringele overreden, maar de mensen van het verzet Gefreiter Hermanns hebben vermoord. Verzetsmensen noemden ze zichzelf, maar het was een stelletje pummels die de mensen in ons dorp in gevaar brachten met het vermoorden van Duitsers en van NSB-ers, omdat ze na de oorlog bij de overwinnaars wilden horen en helden wilden zijn. Grootmoeder weet er alles van. Voor elke moord kregen wij de rekening betaald. Het bloed van Gefreiter Hermanns zat op de ruiten van de Végé winkel, en dat hebben ze, bang om het bloed van een mens aan te raken, laten zitten tot het eraf geregend was. Maar ik denk dat Graad Stevens, de winkelier van de Végé, een winkel in koloniale waren en slachtafval dat nog net geschikt is voor menselijke consumptie en dat door de vrouwen van de arbeiders van de steenfabriek wordt gekocht omdat ze zelfs geen spek kunnen betalen, de mensen naar zijn etalage wilde lokken, om ze met aanbiedingen naar binnen te halen. Daar kots ik van. Stevens heeft altijd van die gruwelijke dingen in de aanbieding, zoals griesmeel, kopvlees, zult zeggen ze in Holland en voorgebakken uier, dat nog goedkoper is dan lever en niertjes. Nadat die Duitser is ontploft, en de SS-ers wraak namen door een paar mannen van de Kerstraat uit huis te halen en dood te schieten, hebben de Amerikanen de oorlog gewonnen, maar grootmoeder zegt nog vaak dat het helemaal niet nodig was geweest om Gefreiter Hermanns op te blazen. De man woonde in Kaldenkirchen en sprak ons dialect. Hij wilde niets weten van d’n Hietteler en was blij dat de Amerikanen de oorlog gingen winnen, want hij wilde naar huis. Maar thuis kregen ze alleen een haarlok van hem en zijn rechterschoen in een vijfkilo suikerzak van de Végé. Net als bij Greijn, daar kreeg de familie van Jan Greijn de soldatenmuts en een militaire onderscheiding vanwege zijn prestaties als scherpschutter uit de tijd toen hij nog soldatenrekruut in Nederland was, maar van zijn tijd in Indonesië, vanaf zijn aankomst met het troepentransport De Grote Beer, die de familie zelf uit de haven van Amsterdam heeft zien vertrekken om Jan na te wuiven, tot het moment dat hij op een mijn liep ergens in de buurt van een kampong waar de Nederlanders alle ploppers wilden gaan afschieten, kregen ze niks, waarschijnlijk omdat er niets meer van hem over was. En toch heeft zijn broer Har vrijwillig dienst genomen in het detachement van Nederlandse militairen die nu in Korea tegen de communisten vechten. Bij Greijn luisteren ze nooit naar de radio. De ouders van Har willen nooit iets over Korea horen en in de nieuwsberichten gaat het juist altijd over Korea, het gele gevaar, en hoe gruwelijk die kleine Koreaanse mannetjes hun gevangenen martelen.

Zelf werk ik ook vaak op de boerenveiling, na schooltijd en op zaterdagmiddag, als we vrij zijn van school. Als de kinderen van de Kerkstraat boeken lezen of op hun blinkende fietsen met bokkenstuur door onze straat fietsen om ons de ogen uit te steken: ze weten dat wij nooit nieuwe fietsen zullen krijgen. Klootzakken zijn het. ‘Er komt niks terecht van die knapzakkinderen,’ zegt mijn moeder altijd ‘Ze zijn lui geboren en zullen nooit weten wat werken is.’ En mieten zijn het ook. Ze staan altijd te kotsen als wij, de jongens van de Ringovenstraat, jonge groene kikkers uit de poelen van de steenfabriek scheppen en opblazen met een strootje in hun kont en ze dan aan het prikkeldraad van de paardenwei van de directeur van de steenfabriek hangen en met een katapult lek schieten. We lachen ons altijd kapot over die kikkers, hoe ze met hun poten trekken, het is net Circus Sarrassani. En dan zingen wij ‘wir werden nach England fahren.’ En die kikkers maar dansen. Laat ze maar pijn hebben, dat hebben wij ook. Vaak kom ik thuis met de blaren in mijn handen van de bezemstelen maar vooral van de riek, die veel te zwaar voor me is. Ik moet het afval van de asperges op karren laden. Het is mannenwerk, maar ik klaag niet, geld is goed voor alles en ik heb het graag over voor mijn moeder. Jezus klaagde ook niet toen hij aan het kruis hing, maar hij had makkelijk praten want hij wist dat hij zo naar de hemel ging en wij blijven maar in de kou zitten. Waarom hangt Jezus overal aan het kruis? Op elke straathoek, in elke huiskamer, is dat niet wat overdreven? Dat lijden van hem heeft toch maar een paar uur geduurd en hier in de straat zijn er die een heel leven lang verrekken. Jezus wíst toch dat hem niets kon gebeuren, maar als je niets te eten hebt, zelfs geen hersens en geen uier en de aardappels met schil moet eten zodat ze ruiken als varkensvoer, dan lijdt je altijd pijn.

De hallen vegen, kuipen uitwassen, het schijthuis schrobben, wat niet helpt omdat de meeste boeren geen schijthuis hebben, thuis schijten ze gewoon tussen de varkens. Ze weten niet eens dat de bril op de pot naar boven en naar beneden kan. Ze zeiken altijd de bril en de muur vol. Ze snappen niet dat je ook in de pot kunt pissen. Vaak ligt de stront naast de pot. Dat moet ik allemaal schoon spuiten. En alles voor een dubbeltje per uur, waar veilingmeester Grubben ook nog vaak een cent van aftrekt omdat ik eigenlijk te klein ben voor dat zware werk, terwijl hij er juist een cent bij zou moeten doen omdat ik dat werk tóch doe ondanks dat ik klein ben. Maar elf dubbeltjes is een gulden en een gulden is veel geld. Je kunt er drie en half grijsbrood voor kopen, of twee witte vloerbroden, maar dat eten wij niet, dat is alleen voor fijne lui met papiergeld in hun kontzak.

‘Hee,’ fluistert moeder aan de deur, ‘lig je nog te prakkezeren, kom op, eruit.’

Ik hoor hoe moeder over de overloop loopt, voorzichtig, om geen lawaai te maken, maar haar blote voeten zuigen aan het zeil en dat maakt juist een rot geluid, net als wanneer je per ongeluk met een gepokte vork langs je tanden trekt, of als je de kurk uit de azijnfles draait. Daar krijg ik altijd rillingen van. Net als nu. Ik voel me altijd koortsig als ze me zo vroeg wakker maakt. Omdat ik nog wil slapen. Omdat ik eindelijk lekker warm ben. Buiten het bed is het altijd koud en krijg ik kippenvel, ook al is het hoogzomer. Moeder vindt dat aanstellerij en mijn broer zegt dat ik de konijnenziekte heb. Konijnen kunnen ook niet tegen de kou. In het hok kruipen ze allemaal op een hoop. Zeker weten dat ze weten dat ze worden opgevreten.