Fleurs du Mal Magazine

![]()

Walter Breedveld over Harrie Kapteijns

DE KUNST VAN HET DICHTEN

door Jef van Kempen

Walter Breedveld (1901-1977) was lange tijd ongekend populair als schrijver van Brabantse volksboeken. Maar Breedveld deed meer. Zo maakte hij in 1959 en 1960 ruim vijftig portretten van Brabantse kunstenaars voor De Gelderlander. Een korte serie belicht deze andere kant van Breedveld. Vandaag: Harrie Kapteijns (1917-1987).

“De dichter is veel meer individualist dan de romanschrijver, niet in de zin dat hij in een glazen huisje wenst te wonen, afkerig van het normale gemeenschapsleven, doch hij is individualist omdat ieder vers eigenlijk een reflectie is van zijn eigen wezen, geschapen voor zich zelf.”

Zo introduceert Walter Breedveld de letterkundige Harrie Kapteijns. Kapteijns was een dichter, maar een die vooral naam zou maken als essayist.

Hij  promoveerde in 1949 met zijn proefschrift Autonome dichters: typen van ‘poètes maudits’ en oogstte veel lof voor zijn in 1964 verschenen studie over het katholieke letterkundige tijdschrift De Gemeenschap. Maar misschien wel zijn belangrijkste publicatie is de in 1951 verschenen becommentarieerde bloemlezing: Hedendaagse Brabantse dichters. Er passeren gevestigde namen de revue van dichters uit de kring van Roeping, De Gemeenschap en Brabantia Nostra, zoals Anton van Duinkerken en Paul Vlemminx. Maar er is ook veel aandacht voor de jonge nieuwe talenten zoals Frans Babylon, Anton Eijkens, Bert Voeten en Harriet Laurey.

promoveerde in 1949 met zijn proefschrift Autonome dichters: typen van ‘poètes maudits’ en oogstte veel lof voor zijn in 1964 verschenen studie over het katholieke letterkundige tijdschrift De Gemeenschap. Maar misschien wel zijn belangrijkste publicatie is de in 1951 verschenen becommentarieerde bloemlezing: Hedendaagse Brabantse dichters. Er passeren gevestigde namen de revue van dichters uit de kring van Roeping, De Gemeenschap en Brabantia Nostra, zoals Anton van Duinkerken en Paul Vlemminx. Maar er is ook veel aandacht voor de jonge nieuwe talenten zoals Frans Babylon, Anton Eijkens, Bert Voeten en Harriet Laurey.

Kapteijns neemt in zijn bloemlezing een duidelijke ontwikkeling van de Brabantse dichtkunst onder de jongeren waar. Volgens Kapteijns: “blijken de jonge dichters anders georiënteerd; hun werk is niet expliciet Brabants, al publiceerden ze in Brabantia Nostra, en soms niet expliciet katholiek, al debuteerden of publiceerden ze in Roeping. Bij de artistieke vormgeving van hun liefde, hun problemen, hun levensinzicht steunen ze niet op de waarden van het gewestelijke”.

Acht jaar later, in een gesprek met Walter Breedveld, is Harrie Kapteijns opmerkelijk minder optimistisch. “Er is weinig eigentijds talent in Brabant. (…) Al wat oudere dichters als Anton van Duinkerken, Frank Valkenier en Lucas van Hoek zwijgen. Hebben ze hun tijd gehad? Verstaan zij de dynamiek van onze dagen niet?” Wat de jongeren betreft blijken de verwachtingen te hoog gespannen te zijn geweest: “In tegenstelling tot de westelijke provincies waar nieuw eigentijds talent aanwijsbaar is. De belangrijkste reden zal ongetwijfeld te vinden zijn in de gemoedelijkheid en de traagzaamheid van de Brabantse aard.”

“De gave van het dichterschap is slechts aan weinigen gegeven” merkt Walter Breedveld op. “De kunst van het dichten is onder de kunsten dan ook wel de moeilijkste, de meest persoonlijke en de minst begrijpelijke vorm van artistiek vermogen.” Breedveld roemt daarna Harrie Kapteijns als een van de meest betekenende Brabantse dichters.

Er zijn in mijn leven

enkele onbenutte kansen

als stille open vijvers,

niet met wrangheid toegevroren,

en niet benaderde,

ongeschonden cijfers,

die tot geen getal behoren.

Jef van Kempen: De kunst van het dichten. Walter Breedveld over Harrie Kapteijns

(Brabants Dagblad, 15 november 2001)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anton van Duinkerken, Babylon, Frans, Brabantia Nostra, Eijkens, Anton, Jef van Kempen, Walter Breedveld

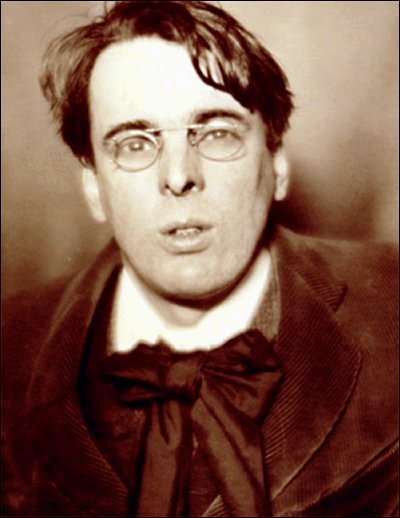

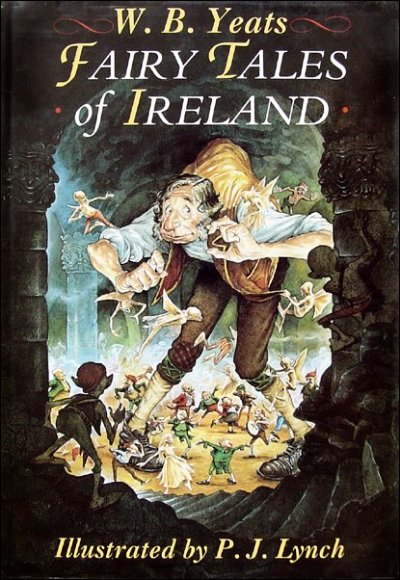

William Butler Yeats

(1865-1939)

5 poems

Alternative song for the severed head

in “The King of the Great Clock Tower”

Saddle and ride, I heard a man say,

Out of Ben Bulben and Knocknarea,

What says the Clock in the Great Clock Tower?

All those tragic characters ride

But turn from Rosses’ crawling tide,

The meet’s upon the mountain-side.

A slow low note and an iron bell.

What brought them there so far from their home.

Cuchulain that fought night long with the foam,

What says the Clock in the Great Clock Tower?

Niamh that rode on it; lad and lass

That sat so still and played at the chess?

What but heroic wantonness?

A slow low note and an iron bell.

Aleel, his Countess; Hanrahan

That seemed but a wild wenching man;

What says the Clock in the Great Clock Tower?

And all alone comes riding there

The King that could make his people stare,

Because he had feathers instead of hair.

A slow low note and an iron bell.

Broken Dreams

There is grey in your hair.

Young men no longer suddenly catch their breath

When you are passing;

But maybe some old gaffer mutters a blessing

Because it was your prayer

Recovered him upon the bed of death.

For your sole sake — that all heart’s ache have known,

And given to others all heart’s ache,

From meagre girlhood’s putting on

Burdensome beauty — for your sole sake

Heaven has put away the stroke of her doom,

So great her portion in that peace you make

By merely walking in a room.

Your beauty can but leave among us

Vague memories, nothing but memories.

A young man when the old men are done talking

Will say to an old man, “Tell me of that lady

The poet stubborn with his passion sang us

When age might well have chilled his blood.”

Vague memories, nothing but memories,

But in the grave all, all, shall be renewed.

The certainty that I shall see that lady

Leaning or standing or walking

In the first loveliness of womanhood,

And with the fervour of my youthful eyes,

Has set me muttering like a fool.

You are more beautiful than any one,

And yet your body had a flaw:

Your small hands were not beautiful,

And I am afraid that you will run

And paddle to the wrist

In that mysterious, always brimming lake

Where those What have obeyed the holy law

paddle and are perfect. Leave unchanged

The hands that I have kissed,

For old sake’s sake.

The last stroke of midnight dies.

All day in the one chair

From dream to dream and rhyme to rhyme I have ranged

In rambling talk with an image of air:

Vague memories, nothing but memories.

The Old Stone Cross

A statesman is an easy man,

He tells his lies by rote;

A journalist makes up his lies

And takes you by the throat;

So stay at home and drink your beer

And let the neighbours vote,

Said the man in the golden breastplate

Under the old stone Cross.

Because this age and the next age

Engender in the ditch,

No man can know a happy man

From any passing wretch;

If Folly link with Elegance

No man knows which is which,

Said the man in the golden breastplate

Under the old stone Cross.

But actors lacking music

Do most excite my spleen,

They say it is more human

To shuffle, grunt and groan,

Not knowing what unearthly stuff

Rounds a mighty scene,

Said the man in the golden breastplate

Under the old stone Cross.

The Mother of God

The threefold terror of love; a fallen flare

Through the hollow of an ear;

Wings beating about the room;

The terror of all terrors that I bore

The Heavens in my womb.

Had I not found content among the shows

Every common woman knows,

Chimney corner, garden walk,

Or rocky cistern where we tread the clothes

And gather all the talk?

What is this flesh I purchased with my pains,

This fallen star my milk sustains,

This love that makes my heart’s blood stop

Or strikes a Sudden chill into my bones

And bids my hair stand up?

Presences

This night has been so strange that it seemed

As if the hair stood up on my head.

From going-down of the sun I have dreamed

That women laughing, or timid or wild,

In rustle of lace or silken stuff,

Climbed up my creaking stair. They had read

All I had rhymed of that monstrous thing

Returned and yet unrequited love.

They stood in the door and stood between

My great wood lectern and the fire

Till I could hear their hearts beating:

One is a harlot, and one a child

That never looked upon man with desire.

And one, it may be, a queen.

W.B. Yeats: five poems

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Y-Z, Yeats, William Butler

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature