Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

XVII. Cornélius Béga

Dans les premiers jours du mois de février 1620, naquit à Haarlem, du mariage de Cornélius Bégyn, sculpteur sur bois, et de Marie Cornélisz, sa femme, un enfant du sexe masculin qui reçut le prénom de Cornélius.

Je ne vous dirai point si le dit enfant piaula de lamentable façon, s’il fut turbulent ou calme, je l’ignore; peu vous importe d’ailleurs et à moi aussi; tout ce que je sais, c’est qu’à l’âge de dix-huit ans, il témoigna d’un goût immodéré pour les arts, les femmes grasses et la bière double.

Le vieux Bégyn et le père de sa femme, le célèbre peintre Cornélisz Van Haarlem, encouragèrent le premier de ces penchants et combattirent vainement les deux autres.

Marie Cornélisz, qui était femme pieuse et versée dans la société des abbés et des moines, essaya, par l’intermédiaire de ces révérends personnages, de ramener son fils dans une voie meilleure. Ce fut peine perdue. Cornélius était plus apte à crier: Tope et masse! à moi, compagnons, buvons ce piot, ha! Guillemette la rousse, montrez vos blancs tétins! qu’à marmotter d’une voix papelarde des patenôtres ou des oraisons.

Menaces, coups, prières, rien n’y fit. Dès qu’il apercevait la cotte d’une paillarde, se moulant en beaux plis serrés le long de fortes hanches, il perdait la tête et courait après la paillarde, laissant là pinceau et palette, pot de grès et broc d’étain. Encore qu’il fût passionné pour la peinture et la beuverie et qu’il admirât plus qu’aucun les chefs-d’oeuvre de Rembrandt et de Hals, et la magnifique ordonnance de tonneaux et de muids bien ventrus, il était plus énamouré encore de lèvres soyeuses et roses, d’épaules charnues et blanches comme les nivéoles qui fleurissent au printemps.

Enfin, quoi qu’il en fût, espérant que la raison viendrait avec l’âge et que l’amour de l’art maîtriserait ces déplorables passions, son père le fit admettre dans l’atelier des Van Ostade. Cornélius ne pouvait trouver un meilleur maître, mais il ne pouvait trouver aussi des camarades plus disposés à courir au four banal et à boire avec les galloises et autres mauvaises filles, folles de leur corps, que ses compagnons d’études, Dusart, Goebauw, Musscher et les autres.

Sa gaieté et ses franches allures leur plurent tout d’abord, et ils se livrèrent, pour célébrer sa bienvenue, à de telles ripailles que la ville entière en fut scandalisée.

Furieux de voir traîner son nom dans les lieux les plus mal famés de Haarlem, le vieux Bégyn défendit à son fils de le porter, et le chassa de chez lui.

Cornélius resta quelques instants pantois et déconcerté, puis il enfonça d’un coup de poing son feutre sur sa tête et s’en fut à la taverne du Houx-Vert où se réunissait la joyeuse confrérie des buveurs.

—Ce qui est fait est fait, clama de sa voix de galoubet aigu le peintre Dusart, lorsqu’il apprit la mésaventure de son ami; puisque ton père te défend de porter son nom, nous allons te baptiser. Veux-tu t’appeler Béga?

—Soit, dit le jeune homme; aussi bien je veux illustrer ce nom; à partir d’aujourd’hui je renonce aux tripots et aux franches repues, je travaille. Un immense éclat de rire emplit le cabaret. «Tu déraisonnes, crièrent ses amis. Est-ce qu’Ostade ne boit pas? est-ce que le grand Hals n’est pas un ivrogne fieffé? est-ce que Brauwer ne fait pas tous les soirs topazes sur l’ongle avec des pintes de bière? cela l’empêche-t-il d’avoir du génie? Non! eh bien! fais comme eux: travaille, mais bois.»

—Ores ça, et moi, dit Marion la grosse, qui se planta vis-à-vis de Cornélius, est-ce qu’on n’embrassera plus les bonnes joues de sa Marion?

—Eh, vrai Dieu! si, je le voudrai toujours! répliqua le jeune homme, qui baisa les grands yeux orange de sa maîtresse et oublia ses belles résolutions aussi vite qu’il les avait prises.

—Ça, qu’on le baptise! criait le peintre Musscher, juché sur un tonneau. Hôtelier, apporte ta bière la plus forte, ton genièvre le plus épicé, que nous arrosions, non point la tête, mais, comme il convient à d’honnêtes biberons, le gosier du néophyte.

L’hôtelier ne se le fit pas dire deux fois; il charria, avec l’aide de ses garçons, une grande barrique de bière, et Béga, flanqué d’un coté de son parrain Dusart, de l’autre de sa marraine Marion la grosse, s’avança du fond de la salle jusqu’aux fonts baptismaux, c’est-à-dire jusqu’à la cuve, où l’attendait l’hôtelier, faisant fonctions de grand prêtre.

Planté sur ses petites jambes massives, roulant de gros yeux verdâtres comme du jade, frottant avec sa manche son petit nez loupeux qui luisait comme bosse de cuivre, balayant de sa large langue ses grosses lèvres humides, cet honorable personnage se lança sans hésiter dans les spirales d’un long discours qui ne tendait rien moins qu’à démontrer l’influence heureuse de la bière et du skidam sur le cerveau des artistes en général et sur celui des peintres en particulier. De longs applaudissements scandèrent les périodes de l’orateur et, après une chaude allocution de la marraine qui scanda elle-même, par de retentissants baisers, appliqués sur les joues de Cornélius, et par des points d’orgue hasardeux, les phrases enrubannées de son discours, le défilé commença aux accents harmonieux d’un violon pleurard et d’une vielle grinçante.

Une année durant, Béga continua à mener joyeuse vie avec ses compagnons; le malheur, c’est qu’il n’avait pas le tempérament de Brauwer, dont le lumineux génie résista aux plus folles débauches. L’impuissance vint vite; quoi qu’il fît, quoi qu’il s’ingéniât à produire, c’était de la piquette d’Ostade; il trempait d’eau la forte bière du vieux maître.

Il en brisa ses pinceaux de rage. Revenu de tout, dégoûté de ses amis, méprisant les filles, reconnaissant enfin qu’une maîtresse est une ennemie et que, plus on fait de sacrifices pour elle, moins elle vous en a de reconnaissance, il s’isola de toutes et de tous et vécut dans la plus complète solitude.

Sa mélancolie s’en accrut encore, et, un soir, plus triste et plus harassé que de coutume, il résolut d’en finir et se dirigea vers la rivière. Il longeait la berge et regardait, en frissonnant, l’eau qui bouillonnait sous les arches du pont. Il allait prendre son élan et sauter, quand il entendit derrière lui un profond soupir et, se retournant, se trouva face à face avec une jeune fille qui pleurait. Il lui demanda la cause de ses larmes et, sur ses instances et ses prières, elle finit par lui avouer que, lasse de supporter les brutalités de sa famille, elle était venue à la rivière avec l’intention de s’y jeter.

Leur commune détresse rapprocha ces deux malheureux, qui s’aimèrent et se consolèrent l’un l’autre. Béga n’était plus reconnaissable. Cet homme qui, un mois auparavant, était la proie de lancinantes angoisses, d’inexorables remords, se prit enfin à goûter les tranquilles délices d’une vie calme. Pour comble de bonheur, son talent se réveilla en même temps que sa jeunesse, et c’est de cette époque que sont datées ses meilleures toiles.

Tout souriait au jeune ménage, honneurs et argent se décidaient enfin à venir, quand soudain la peste éclata dans Haarlem.

La pauvre fille en fut atteinte. Béga s’installa à son chevet et ne la quitta plus. La mort était proche. Il voulut se jeter dans les bras de sa bien-aimée, la serrer contre sa poitrine, respirer l’haleine de sa bouche, mourir sur son sein: ses amis l’en empêchèrent. «Je veux mourir avec elle, criait-il, je veux mourir!» Il supplia ceux qui le retenaient de lui rendre sa liberté. «Je vous jure, dit-il, que je ne l’approcherai point.» Il prit alors un bâton, en posa une des extrémités sur la bouche de la mourante et la supplia de l’embrasser. Elle sourit tristement et lui obéit; par trois fois elle effleura le bâton de ses lèvres; alors il le porta vivement aux siennes et les colla furieusement à la place qu’elle avait baisée.

Honbraken, qui rapporte ce fait, ajoute que, frappé de douleur, Béga fut lui même atteint de la peste, et qu’il expira quelques jours après.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

Together and Apart

Mrs. Dalloway introduced them, saying you will like him. The conversation began some minutes before anything was said, for both Mr. Serle and Miss Arming looked at the sky and in both of their minds the sky went on pouring its meaning though very differently, until the presence of Mr. Serle by her side became so distinct to Miss Anning that she could not see the sky, simply, itself, any more, but the sky shored up by the tall body, dark eyes, grey hair, clasped hands, the stern melancholy (but she had been told “falsely melancholy”) face of Roderick Serle, and, knowing how foolish it was, she yet felt impelled to say:

“What a beautiful night!”

Foolish! Idiotically foolish! But if one mayn’t be foolish at the age of forty in the presence of the sky, which makes the wisest imbecile—mere wisps of straw—she and Mr. Serle atoms, motes, standing there at Mrs. Dalloway’s window, and their lives, seen by moonlight, as long as an insect’s and no more important.

“Well!” said Miss Anning, patting the sofa cushion emphatically. And down he sat beside her. Was he “falsely melancholy,” as they said? Prompted by the sky, which seemed to make it all a little futile—what they said, what they did—she said something perfectly commonplace again:

“There was a Miss Serle who lived at Canterbury when I was a girl there.”

With the sky in his mind, all the tombs of his ancestors immediately appeared to Mr. Serle in a blue romantic light, and his eyes expanding and darkening, he said: “Yes.

“We are originally a Norman family, who came over with the Conqueror. That is a Richard Serle buried in the Cathedral. He was a knight of the garter.”

Miss Arming felt that she had struck accidentally the true man, upon whom the false man was built. Under the influence of the moon (the moon which symbolized man to her, she could see it through a chink of the curtain, and she took dips of the moon) she was capable of saying almost anything and she settled in to disinter the true man who was buried under the false, saying to herself: “On, Stanley, on”—which was a watchword of hers, a secret spur, or scourge such as middle–aged people often make to flagellate some inveterate vice, hers being a deplorable timidity, or rather indolence, for it was not so much that she lacked courage, but lacked energy, especially in talking to men, who frightened her rather, and so often her talks petered out into dull commonplaces, and she had very few men friends—very few intimate friends at all, she thought, but after all, did she want them? No. She had Sarah, Arthur, the cottage, the chow and, of course THAT, she thought, dipping herself, sousing herself, even as she sat on the sofa beside Mr. Serle, in THAT, in the sense she had coming home of something collected there, a cluster of miracles, which she could not believe other people had (since it was she only who had Arthur, Sarah, the cottage, and the chow), but she soused herself again in the deep satisfactory possession, feeling that what with this and the moon (music that was, the moon), she could afford to leave this man and that pride of his in the Serles buried. No! That was the danger—she must not sink into torpidity—not at her age. “On, Stanley, on,” she said to herself, and asked him:

“Do you know Canterbury yourself?”

Did he know Canterbury! Mr. Serle smiled, thinking how absurd a question it was—how little she knew, this nice quiet woman who played some instrument and seemed intelligent and had good eyes, and was wearing a very nice old necklace—knew what it meant. To be asked if he knew Canterbury. When the best years of his life, all his memories, things he had never been able to tell anybody, but had tried to write—ah, had tried to write (and he sighed) all had centred in Canterbury; it made him laugh.

His sigh and then his laugh, his melancholy and his humour, made people like him, and he knew it, and vet being liked had not made up for the disappointment, and if he sponged on the liking people had for him (paying long calls on sympathetic ladies, long, long calls), it was half bitterly, for he had never done a tenth part of what he could have done, and had dreamed of doing, as a boy in Canterbury. With a stranger he felt a renewal of hope because they could not say that he had not done what he had promised, and yielding to his charm would give him a fresh startat fifty! She had touched the spring. Fields and flowers and grey buildings dripped down into his mind, formed silver drops on the gaunt, dark walls of his mind and dripped down. With such an image his poems often began. He felt the desire to make images now, sitting by this quiet woman.

“Yes, I know Canterbury,” he said reminiscently, sentimentally, inviting, Miss Anning felt, discreet questions, and that was what made him interesting to so many people, and it was this extraordinary facility and responsiveness to talk on his part that had been his undoing, so he thought often, taking his studs out and putting his keys and small change on the dressing–table after one of these parties (and he went out sometimes almost every night in the season), and, going down to breakfast, becoming quite different, grumpy, unpleasant at breakfast to his wife, who was an invalid, and never went out, but had old friends to see her sometimes, women friends for the most part, interested in Indian philosophy and different cures and different doctors, which Roderick Serle snubbed off by some caustic remark too clever for her to meet, except by gentle expostulations and a tear or two—he had failed, he often thought, because he could not cut himself off utterly from society and the company of women, which was so necessary to him, and write. He had involved himself too deep in life—and here he would cross his knees (all his movements were a little unconventional and distinguished) and not blame himself, but put the blame off upon the richness of his nature, which he compared favourably with Wordsworth’s, for example, and, since he had given so much to people, he felt, resting his head on his hands, they in their turn should help him, and this was the prelude, tremulous, fascinating, exciting, to talk; and images bubbled up in his mind.

“She’s like a fruit tree—like a flowering cherry tree,” he said, looking at a youngish woman with fine white hair. It was a nice sort of image, Ruth Anning thought—rather nice, yet she did not feel sure that she liked this distinguished, melancholy man with his gestures; and it’s odd, she thought, how one’s feelings are influenced. She did not like HIM, though she rather liked that comparison of his of a woman to a cherry tree. Fibres of her were floated capriciously this way and that, like the tentacles of a sea anemone, now thrilled, now snubbed, and her brain, miles away, cool and distant, up in the air, received messages which it would sum up in time so that, when people talked about Roderick Serle (and he was a bit of a figure) she would say unhesitatingly: “I like him,” or “I don’t like him,” and her opinion would be made up for ever. An odd thought; a solemn thought; throwing a green light on what human fellowship consisted of.

“It’s odd that you should know Canterbury,” said Mr. Serle. “It’s always a shock,” he went on (the white–haired lady having passed), “when one meets someone” (they had never met before), “by chance, as it were, who touches the fringe of what has meant a great deal to oneself, touches accidentally, for I suppose Canterbury was nothing but a nice old town to you. So you stayed there one summer with an aunt?” (That was all Ruth Anning was going to tell him about her visit to Canterbury.) “And you saw the sights and went away and never thought of it again.”

Let him think so; not liking him, she wanted him to run away with an absurd idea of her. For really, her three months in Canterbury had been amazing. She remembered to the last detail, though it was merely a chance visit, going to see Miss Charlotte Serle, an acquaintance of her aunt’s. Even now she could repeat Miss Serle’s very words about the thunder. “Whenever I wake, or hear thunder in the night, I think ‘Someone has been killed’.” And she could see the hard, hairy, diamond–patterned carpet, and the twinkling, suffused, brown eyes of the elderly lady, holding the teacup out unfilled, while she said that about the thunder. And always she saw Canterbury, all thundercloud and livid apple blossom, and the long grey backs of the buildings.

The thunder roused her from her plethoric middleaged swoon of indifference; “On, Stanley, on,” she said to herself; that is, this man shall not glide away from me, like everybody else, on this false assumption; I will tell him the truth.

“I loved Canterbury,” she said.

He kindled instantly. It was his gift, his fault, his destiny.

“Loved it,” he repeated. “I can see that you did.”

Her tentacles sent back the message that Roderick Serle was nice.

Their eyes met; collided rather, for each felt that behind the eyes the secluded being, who sits in darkness while his shallow agile companion does all the tumbling and beckoning, and keeps the show going, suddenly stood erect; flung off his cloak; confronted the other. It was alarming; it was terrific. They were elderly and burnished into a glowing smoothness, so that Roderick Serle would go, perhaps to a dozen parties in a season, and feel nothing out of the common, or only sentimental regrets, and the desire for pretty images—like this of the flowering cherry tree—and all the time there stagnated in him unstirred a sort of superiority to his company, a sense of untapped resources, which sent him back home dissatisfied with life, with himself, yawning, empty, capricious. But now, quite suddenly, like a white bolt in a mist (but this image forged itself with the inevitability of lightning and loomed up), there it had happened; the old ecstasy of life; its invincible assault; for it was unpleasant, at the same time that it rejoiced and rejuvenated and filled the veins and nerves with threads of ice and fire; it was terrifying. “Canterbury twenty years ago,” said Miss Anning, as one lays a shade over an intense light, or covers some burning peach with a green leaf, for it is too strong, too ripe, too full.

Sometimes she wished she had married. Sometimes the cool peace of middle life, with its automatic devices for shielding mind and body from bruises, seemed to her, compared with the thunder and the livid appleblossom of Canterbury, base. She could imagine something different, more like lightning, more intense. She could imagine some physical sensation. She could imagine——

And, strangely enough, for she had never seen him before, her senses, those tentacles which were thrilled and snubbed, now sent no more messages, now lay quiescent, as if she and Mr. Serle knew each other so perfectly, were, in fact, so closely united that they had only to float side by side down this stream.

Of all things, nothing is so strange as human intercourse, she thought, because of its changes, its extraordinary irrationality, her dislike being now nothing short of the most intense and rapturous love, but directly the word “love” occurred to her, she rejected it, thinking again how obscure the mind was, with its very few words for all these astonishing perceptions, these alternations of pain and pleasure. For how did one name this. That is what she felt now, the withdrawal of human affection, Serle’s disappearance, and the instant need they were both under to cover up what was so desolating and degrading to human nature that everyone tried to bury it decently from sight—this withdrawal, this violation of trust, and, seeking some decent acknowledged and accepted burial form, she said:

“Of course, whatever they may do, they can’t spoil Canterbury.”

He smiled; he accepted it; he crossed his knees the other way about. She did her part; he his. So things came to an end. And over them both came instantly that paralysing blankness of feeling, when nothing bursts from the mind, when its walls appear like slate; when vacancy almost hurts, and the eyes petrified and fixed see the same spot—a pattern, a coal scuttle—with an exactness which is terrifying, since no emotion, no idea, no impression of any kind comes to change it, to modify it, to embellish it, since the fountains of feeling seem sealed and as the mind turns rigid, so does the body; stark, statuesque, so that neither Mr. Serle nor Miss Anning could move or speak, and they felt as if an enchanter had freed them, and spring flushed every vein with streams of life, when Mira Cartwright, tapping Mr. Serle archly on the shoulder, said:

“I saw you at the Meistersinger, and you cut me. Villain,” said Miss Cartwright, “you don’t deserve that I should ever speak to you again.”

And they could separate.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: A Haunted House, and other short stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

XVI. Adrien Brauwer

I

Deux compagnons, l’un maigre et élancé comme une cigogne, l’autre obèse et ventru comme un muid, galopent sur la route de Flandre, en pétunant dans de longues pipes. Leur mine est rien moins qu’honnête. Le grand a la figure régulière, mais ravagée par les orgies, l’air hautain et distingué; le gros a l’air commun, la face purpurée, le nez étincelant comme une braise et fleuri de pompettes écarlates. Quant à l’accoutrement des deux sires, il tombe en lambeaux. L’homme maigre est vêtu d’un pourpoint qui, jadis, a dû réjouir les belles par ses teintes incarnadines; mais la poussière et les libations l’ont revêtu de tons roux et fuligineux; ses grègues baissent le nez piteusement, ses souliers sont feuilletés et rient à semelles déployées. Le gros, vêtu de loques dont on ne saurait définir la nuance exacte, a pourtant des chausses dont la couleur primitive a dû être un jaune citrin agrémenté de rubans pers, mais elles sont si vieillies, si fourbues, si usées, que nous n’oserions assurer qu’elles aient eu ces teintes agréables dans leur jeunesse.

—C’est étonnant, dit le gros, comme la poussière vous sèche le gosier! qu’un broc de cervoise serait bienvenu! Hé! mon maître, invoquez le divin Gambrinus pour qu’il conduise nos pas à un cabaret.

—Eh! dit Brauwer, tu sais bien que les incomparables Kaatje et Barbara ont vidé nos poches à Anvers.

—Bah! tu peindras un tableau, et nous boirons à notre soif.

—Non, dit le maître, j’ai créé assez de chefs-d’oeuvre laissés dans les cabarets pour payer les breuvages. A ton tour, Kraesbeck, peins et paie l’écot.

—Hélas! tu sais bien que j’ai les bras encore endoloris des coups que j’ai reçus pour avoir voulu embrasser la jolie Betje.

—C’est vrai, dit Brauwer en riant, mais ne discutons pas davantage: voici un cabaret, buvons d’abord, nous verrons à payer ensuite.

Ils entrèrent. La salle était pleine et tellement enfumée qu’on aurait pu y saurer des harengs. Les jambes allongées, le feutre enfoncé jusqu’aux yeux, des personnages en guenilles fumaient à perdre haleine et buvaient en criant et se disputant. Une servante en train de guéer du linge dans la salle voisine rythmait à coups de palettes les chansons que nasillaient quelques-uns de ces marauds. Coutumiers de semblable spectacle, le maître et l’élève ne s’en étonnèrent pas et, pendant quelque temps, pétunèrent et vidèrent tant de pintes qu’ils conquirent l’admiration des malandrins qui peuplaient ce bouge; puis Kroesbeck poussa son maître du coude et lui dit: «S’il ne s’agissait que de boire, la terre serait un paradis; mais il faut payer. Voyons, fais un tableau.» Brauwer poussa un soupir et, prenant une petite toile, se mit à peindre vivement la tabagie.

Ce tableau, vous le connaissez. Il est au Louvre. Le personnage le plus saillant est un buveur assis sur une barrique renversée et nous tournant le dos. Le rustre a tant de fois pétuné et tant de fois vidé de larges vidrecomes qu’il a été choir, nez en avant, sur la table qui lui sert d’appui. Sa chemise a remonté et sort toute bouffante entre son haut-de-chausse jaune paille et son pourpoint gris fer; un autre maraud, plus intrépide, nous n’osons dire plus sobre, allume sa pipe à un brasier rougeâtre et semble absorbé par cette grave occupation. Un troisième nous présente son profil camard et souffle au plafond un nuage de fumée tourbillonnante. Enfin, apparaissent, dans la brume qui enveloppe la tabagie, quelques paysans causant avec une petite fille qui se laisse sans répugnance embrasser par l’un de ces truands.

—Parfait! s’écria Kroesbeck, en se posant devant le tableau. Ah! Adrien, tu as le don du génie. Hals, ton maître, n’était qu’un enfant auprès de toi. Hélas! jamais je ne t’égalerai. Et le pauvre Kroesbeck alla s’asseoir dans un coin, d’un air tout contrit.

Les buveurs étaient partis presque tous. La nuit était venue et l’on n’entendait que le crépitement de la pluie sur les vitres et le pétillement des fagots dans l’âtre. La porte s’ouvrit, et un homme de haute taille entra et vint s’asseoir au coin du feu. Au bout de quelques instants, il se leva et vint se placer derrière Brauwer. «Eh! bien maître, dit-il, comment vous portez-vous?» Notre peintre, qui, pour beaucoup de raisons, ne s’entendait jamais appeler sans effroi, regarda timidement son interlocuteur et reconnut M. de Vermandois, un riche seigneur qui, le premier, lui avait payé en reluisants ducatons un de ses petits chefs-d’oeuvre, alors qu’il fuyait la maison de son maître. «Il est charmant, ce tableau! reprit le gentilhomme; je l’achète; le prix que vous fixerez sera le mien, apportez-le-moi demain matin.» Puis, comme la pluie avait cessé, il sortit, faisant de la main à Brauwer un geste amical.

Tout joyeux de cette aubaine, le peintre fit frémir d’un coup de poing les brocs et les verres qui couvraient la table et redemanda de la bière. «Hé! que dis-tu de cela, Joseph? s’écria-t-il, nous sommes riches, livrons-nous a de francs soulas, buvons papaliter.» Mais Kroesbeck avait disparu. «Où diable est-il?» murmura notre héros, qui se leva en chancelant; mais il buta du pied contre une masse énorme qui, le nez aplati contre le plancher, les bras étendus, les jambes écartées, ronflait mélodieusement; c’était le digne Joseph qui avait roulé sous là table et venait d’ajouter sans doute un nouveau rubis aux innombrables fleurons qui décoraient son nez. Brauwer le regarda avec attendrissement et, bredouillant et dodelinant la tête, alla choir sur un escabeau où il s’endormit.

II

—…A propos de Van Dyck, dit M. de Vermandois, j’ai vu son maître dernièrement. Il regrette, non moins vivement que moi, que vous ayez quitté son palais pour aller, à l’aventure, courir les cabarets et les auberges.

—C’est vrai, dit Brauwer; Rubens s’est conduit avec moi comme un véritable ami, comme un grand artiste; mais ses disciples vêtus de soie et de velours m’intimidaient. Aurais-je pu peindre, dans ce somptueux atelier, ces trognes grimaçantes, ces haillons bizarres, ces postures si grotesques et si naturelles de l’ivrogne qu’elles vous font involontairement sourire; aurais-je pu rendre avec autant de verve cette réalité pittoresque que vous admirez? Que voulez-vous! l’inspiration me désertait sous les lambris, elle me hantait dans les tripots.

A ce moment, la porte s’ouvrit, et une jeune fille parut et fit mine de se retirer en voyant son père causer avec un inconnu.

Sur un signe de M. de Vermandois, elle entra. Brauwer fut ébloui; lui qui n’avait jamais fréquenté que des filles de joie, il resta muet d’admiration devant cette charmante jeune fille. Encadrez un ovale d’une pureté raphaélesque de grandes tresses mordorées, imaginez de grands yeux bleu turquoise, une bouche rouge comme l’aile du flamant, vous n’aurez qu’un faible aperçu de la jolie Jenny.

Le peintre comprit qu’on pouvait être heureux sans vivre dans les bordeaux et faire carrousse avec de joyeux vauriens. Il se promit de quitter sa vie aventureuse et peut-être, pensait-il, parviendrai-je, grâce à mon génie, à ne point lui déplaire. Il quitta cette maison, les larmes aux yeux, et loua une mansarde où, pendant trois jours, il s’enferma. Le troisième jour, malgré quelques regrets, il résista au désir d’aller retrouver son compagnon, l’ex-boulanger Kroesbeck. Il se mit à la fenêtre, alluma sa pipe et regarda dans la rue. Son gîte était mal choisi: un cabaret faisait face à la chambre qu’il habitait, regorgeant de buveurs et d’éhontés tortillons. Au milieu d’eux, un homme à l’encolure puissante, au bedon piriforme, au nez tout emperlé, lançait d’épaisses bouffées et suçait avec de doux vagissements les goulots d’une énorme guédousle. Sa grosse figure rayonnait d’aise. «Tiens, se dit Brauwer, Kroesbeck est ici! Il s’est donc décidé à peindre et à payer l’écot?» Puis il le regarda boire et un sourire d’envie passa sur ses lèvres. Il s’éloigna de la fenêtre et voulut se remettre a travailler. Il n’y put tenir, il regarda de nouveau dans la rue. Son élève l’aperçut.

—Oh! oh! oh! dit-il sur trois tons différents; et, poussant un cri Joyeux, il l’appela. Pour le coup, c’était trop. Brauwer descendit quatre à quatre, et, saisissant un broc, il le vida, la face épanouie, l’oeil pétillant. Une heure après, il dormait dans un coin, complètement ivre.

Le réveil fut moins gai. Il fit silencieusement un paquet de ses hardes et quitta la ville le soir même.

Quinze jours après, il était de retour à Anvers et mourait à l’hôpital. Cet homme de génie fut enterré dans le cimetière des pestiférés, sur une couche de chaux vive.

Joris-Karl Huysmans: Le Drageoir aux épices

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K.

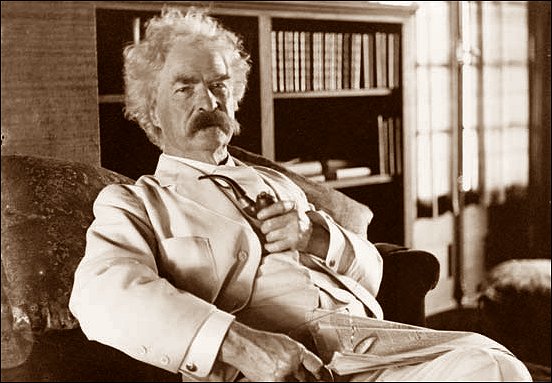

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

Saint Joan of Arc

I

The evidence furnished at the Trials and Rehabilitation sets forth Joan of Arc’s strange and beautiful history in clear and minute detail. Among all the multitude of biographies that freight the shelves of the world’s libraries, this is the only one whose validity is confirmed to us by oath. It gives us a vivid picture of a career and a personality of so extraordinary a character that we are helped to accept them as actualities by the very fact that both are beyond the inventive reach of fiction. The public part of the career occupied only a mere breath of time—it covered but two years; but what a career it was! The personality which made it possible is one to be reverently studied, loved, and marvelled at, but not to be wholly understood and accounted for by even the most searching analysis.

Note.—The Official Record of the Trials and Rehabilitation of Joan of Arc is the most remarkable history that exists in any language; yet there are few people in the world who can say they have read it: in England and America it has hardly been heard of.

Three hundred years ago Shakespeare did not know the true story of Joan of Arc; in his day it was unknown even in France. For four hundred years it existed rather as a vaguely defined romance than as definite and authentic history. The true story remained buried in the official archives of France from the Rehabilitation of 1456 until Quicherat dug it out and gave it to the world two generations ago, in lucid and understandable modern French. It is a deeply fascinating story. But only in the Official Trials and Rehabilitation can it be found in its entirety.—M. T.

In Joan of Arc at the age of sixteen there was no promise of a romance. She lived in a dull little village on the frontiers of civilization; she had been nowhere and had seen nothing; she knew none but simple shepherd folk; she had never seen a person of note; she hardly knew what a soldier looked like; she had never ridden a horse, nor had a warlike weapon in her hand; she could neither read nor write: she could spin and sew; she knew her catechism and her prayers and the fabulous histories of the saints, and this was all her learning. That was Joan at sixteen. What did she know of law? of evidence? of courts? of the attorney’s trade? of legal procedure? Nothing. Less than nothing. Thus exhaustively equipped with ignorance, she went before the court at Toul to contest a false charge of breach of promise of marriage; she conducted her cause herself, without any one’s help or advice or any one’s friendly sympathy, and won it. She called no witnesses of her own, but vanquished the prosecution by using with deadly effectiveness its own testimony. The astonished judge threw the case out of court, and spoke of her as “this marvellous child.”

She went to the veteran Commandant of Vaucouleurs and demanded an escort of soldiers, saying she must march to the help of the King of France, since she was commissioned of God to win back his lost kingdom for him and set the crown upon his head. The Commandant said, “What, you? you are only a child.” And he advised that she be taken back to her village and have her ears boxed. But she said she must obey God, and would come again, and again, and yet again, and finally she would get the soldiers. She said truly. In time he yielded, after months of delay and refusal, and gave her the soldiers; and took off his sword and gave her that, and said, “Go—and let come what may.” She made her long and perilous journey through the enemy’s country, and spoke with the King, and convinced him. Then she was summoned before the University of Poitiers to prove that she was commissioned of God and not of Satan, and daily during three weeks she sat before that learned congress unafraid, and capably answered their deep questions out of her ignorant but able head and her simple and honest heart; and again she won her case, and with it the wondering admiration of all that august company.

And now, aged seventeen, she was made Commander-in-Chief, with a prince of the royal house and the veteran generals of France for subordinates; and at the head of the first army she had ever seen, she marched to Orleans, carried the commanding fortresses of the enemy by storm in three desperate assaults, and in ten days raised a siege which had defied the might of France for seven months.

After a tedious and insane delay caused by the King’s instability of character and the treacherous counsels of his ministers, she got permission to take the field again. She took Jargeau by storm; then Meung; she forced Beaugency to surrender; then—in the open field—she won the memorable victory of Patay against Talbot, “the English lion,” and broke the back of the Hundred Years’ War. It was a campaign which cost but seven weeks of time; yet the political results would have been cheap if the time expended had been fifty years. Patay, that unsung and now long-forgotten battle, was the Moscow of the English power in France; from the blow struck that day it was destined never to recover. It was the beginning of the end of an alien dominion which had ridden France intermittently for three hundred years.

Then followed the great campaign of the Loire, the capture of Troyes by assault, and the triumphal march past surrendering towns and fortresses to Rheims, where Joan put the crown upon her King’s head in the Cathedral, amid wild public rejoicings, and with her old peasant father there to see these things and believe his eyes if he could. She had restored the crown and the lost sovereignty; the King was grateful for once in his shabby poor life, and asked her to name her reward and have it. She asked for nothing for herself, but begged that the taxes of her native village might be remitted forever. The prayer was granted, and the promise kept for three hundred and sixty years. Then it was broken, and remains broken to-day. France was very poor then, she is very rich now; but she has been collecting those taxes for more than a hundred years.

Joan asked one other favor: that now that her mission was fulfilled she might be allowed to go back to her village and take up her humble life again with her mother and the friends of her childhood; for she had no pleasure in the cruelties of war, and the sight of blood and suffering wrung her heart. Sometimes in battle she did not draw her sword, lest in the splendid madness of the onset she might forget herself and take an enemy’s life with it. In the Rouen Trials, one of her quaintest speeches—coming from the gentle and girlish source it did—was her naive remark that she had “never killed any one.” Her prayer for leave to go back to the rest and peace of her village home was not granted.

Then she wanted to march at once upon Paris, take it, and drive the English out of France. She was hampered in all the ways that treachery and the King’s vacillation could devise, but she forced her way to Paris at last, and fell badly wounded in a successful assault upon one of the gates. Of course her men lost heart at once—she was the only heart they had. They fell back. She begged to be allowed to remain at the front, saying victory was sure. “I will take Paris now or die!” she said. But she was removed from the field by force; the King ordered a retreat, and actually disbanded his army. In accordance with a beautiful old military custom Joan devoted her silver armor and hung it up in the Cathedral of St. Denis. Its great days were over.

Then, by command, she followed the King and his frivolous court and endured a gilded captivity for a time, as well as her free spirit could; and whenever inaction became unbearable she gathered some men together and rode away and assaulted a stronghold and captured it.

At last in a sortie against the enemy, from Compiègne, on the 24th of May (when she was turned eighteen), she was herself captured, after a gallant fight. It was her last battle. She was to follow the drums no more.

Thus ended the briefest epoch-making military career known to history. It lasted only a year and a month, but it found France an English province, and furnishes the reason that France is France today and not an English province still. Thirteen months! It was, indeed, a short career; but in the centuries that have since elapsed five hundred millions of Frenchmen have lived and died blest by the benefactions it conferred; and so long as France shall endure, the mighty debt must grow. And France is grateful; we often hear her say it. Also thrifty: she collects the Domrémy taxes.

II

Joan was fated to spend the rest of her life behind bolts and bars. She was a prisoner of war, not a criminal, therefore hers was recognized as an honorable captivity. By the rules of war she must be held to ransom, and a fair price could not be refused it offered. John of Luxembourg paid her the just compliment of requiring a prince’s ransom for her. In that day that phrase represented a definite sum—61,125 francs. It was, of course, supposable that either the King or grateful France, or both, would fly with the money and set their fair young benefactor free. But this did not happen. In five and a half months neither King nor country stirred a hand nor offered a penny. Twice Joan tried to escape. Once by a trick she succeeded for a moment, and locked her jailer in behind her, but she was discovered and caught; in the other case she let herself down from a tower sixty feet high, but her rope was too short, and she got a fall that disabled her and she could not get away.

Finally, Cauchon, Bishop of Beauvais, paid the money and bought Joan—ostensibly for the Church, to be tried for wearing male attire and for other impieties, but really for the English, the enemy into whose hands the poor girl was so piteously anxious not to fall. She was now shut up in the dungeons of the Castle of Rouen and kept in an iron cage, with her hands and feet and neck chained to a pillar; and from that time forth during all the months of her imprisonment, till the end, several rough English soldiers stood guard over her night and day—and not outside her room, but in it. It was a dreary and hideous captivity, but it did not conquer her: nothing could break that invincible spirit. From first to last she was a prisoner a year; and she spent the last three months of it on trial for her life before a formidable array of ecclesiastical judges, and disputing the ground with them foot by foot and inch by inch with brilliant generalship and dauntless pluck. The spectacle of that solitary girl, forlorn and friendless, without advocate or adviser, and without the help and guidance of any copy of the charges brought against her or rescript of the complex and voluminous daily proceedings of the court to modify the crushing strain upon her astonishing memory, fighting that long battle serene and undismayed against these colossal odds, stands alone in its pathos and its sublimity; it has nowhere its mate, either in the annals of fact or in the inventions of fiction.

And how fine and great were the things she daily said, how fresh and crisp—and she so worn in body, so starved, and tired, and harried! They run through the whole gamut of feeling and expression—from scorn and defiance, uttered with soldierly fire and frankness, all down the scale to wounded dignity clothed in words of noble pathos; as, when her patience was exhausted by the pestering delvings and gropings and searchings of her persecutors to find out what kind of devil’s witchcraft she had employed to rouse the war spirit in her timid soldiers, she burst out with, “What I said was, ‘Ride these English down’—and I did it myself!” and as, when insultingly asked why it was that her standard had place at the crowning of the King in the Cathedral of Rheims rather than the standards of the other captains, she uttered that touching speech, “It had borne the burden, it had earned the honor”—a phrase which fell from her lips without premeditation, yet whose moving beauty and simple grace it would bankrupt the arts of language to surpass.

Although she was on trial for her life, she was the only witness called on either side; the only witness summoned to testify before a packed jury commissioned with a definite task: to find her guilty, whether she was guilty or not. She must be convicted out of her own mouth, there being no other way to accomplish it. Every advantage that learning has over ignorance, age over youth, experience over inexperience, chicane over artlessness, every trick and trap and gin devisable by malice and the cunning of sharp intellects practised in setting snares for the unwary—all these were employed against her without shame; and when these arts were one by one defeated by the marvellous intuitions of her alert and penetrating mind, Bishop Cauchon stooped to a final baseness which it degrades human speech to describe: a priest who pretended to come from the region of her own home and to be a pitying friend and anxious to help her in her sore need was smuggled into her cell, and he misused his sacred office to steal her confidence; she confided to him the things sealed from revealment by her Voices, and which her prosecutors had tried so long in vain to trick her into betraying. A concealed confederate set it all down and delivered it to Cauchon, who used Joan’s secrets, thus obtained, for her ruin.

Throughout the Trials, whatever the foredoomed witness said was twisted from its true meaning when possible, and made to tell against her; and whenever an answer of hers was beyond the reach of twisting it was not allowed to go upon the record. It was upon one of these latter occasions that she uttered that pathetic reproach—to Cauchon: “Ah, you set down everything that is against me, but you will not set down what is for me.”

That this untrained young creature’s genius for war was wonderful, and her generalship worthy to rank with the ripe products of a tried and trained military experience, we have the sworn testimony of two of her veteran subordinates—one, the Duc d’Alençon, the other the greatest of the French generals of the time, Dunois, Bastard of Orleans; that her genius was as great—possibly even greater—in the subtle warfare of the forum we have for witness the records of the Rouen Trials, that protracted exhibition of intellectual fence maintained with credit against the master-minds of France; that her moral greatness was peer to her intellect we call the Rouen Trials again to witness, with their testimony to a fortitude which patiently and steadfastly endured during twelve weeks the wasting forces of captivity, chains, loneliness, sickness, darkness, hunger, thirst, cold, shame, insult, abuse, broken sleep, treachery, ingratitude, exhausting sieges of cross-examination, the threat of torture, with the rack before her and the executioner standing ready: yet never surrendering, never asking quarter, the frail wreck of her as unconquerable the last day as was her invincible spirit the first.

Great as she was in so many ways, she was perhaps even greatest of all in the lofty things just named—her patient endurance, her steadfastness, her granite fortitude. We may not hope to easily find her mate and twin in these majestic qualities; where we lift our eyes highest we find only a strange and curious contrast—there in the captive eagle beating his broken wings on the Rock of St. Helena.

III

The Trials ended with her condemnation. But as she had conceded nothing, confessed nothing, this was victory for her, defeat for Cauchon. But his evil resources were not yet exhausted. She was persuaded to agree to sign a paper of slight import, then by treachery a paper was substituted which contained a recantation and a detailed confession of everything which had been charged against her during the Trials and denied and repudiated by her persistently during the three months; and this false paper she ignorantly signed. This was a victory for Cauchon. He followed it eagerly and pitilessly up by at once setting a trap for her which she could not escape. When she realized this she gave up the long struggle, denounced the treason which had been practised against her, repudiated the false confession, reasserted the truth of the testimony which she had given in the Trials, and went to her martyrdom with the peace of God in her tired heart, and on her lips endearing words and loving prayers for the cur she had crowned and the nation of ingrates she had saved.

When the fires rose about her and she begged for a cross for her dying lips to kiss, it was not a friend but an enemy, not a Frenchman but an alien, not a comrade in arms but an English soldier, that answered that pathetic prayer. He broke a stick across his knee, bound the pieces together in the form of the symbol she so loved, and gave it her; and his gentle deed is not forgotten, nor will be.

IV

Twenty-Five years afterwards the Process of Rehabilitation was instituted, there being a growing doubt as to the validity of a sovereignty that had been rescued and set upon its feet by a person who had been proven by the Church to be a witch and a familiar of evil spirits. Joan’s old generals, her secretary, several aged relations and other villagers of Domrémy, surviving judges and secretaries of the Rouen and Poitiers Processes—a cloud of witnesses, some of whom had been her enemies and persecutors,—came and made oath and testified; and what they said was written down. In that sworn testimony the moving and beautiful history of Joan of Arc is laid bare, from her childhood to her martyrdom. From the verdict she rises stainlessly pure, in mind and heart, in speech and deed and spirit, and will so endure to the end of time.

She is the Wonder of the Ages. And when we consider her origin, her early circumstances, her sex, and that she did all the things upon which her renown rests while she was still a young girl, we recognize that while our race continues she will be also the Riddle of the Ages. When we set about accounting for a Napoleon or a Shakespeare or a Raphael or a Wagner or an Edison or other extraordinary person, we understand that the measure of his talent will not explain the whole result, nor even the largest part of it; no, it is the atmosphere in which the talent was cradled that explains; it is the training which it received while it grew, the nurture it got from reading, study, example, the encouragement it gathered from self- recognition and recognition from the outside at each stage of its development: when we know all these details, then we know why the man was ready when his opportunity came. We should expect Edison’s surroundings and atmosphere to have the largest share in discovering him to himself and to the world; and we should expect him to live and die undiscovered in a land where an inventor could find no comradeship, no sympathy, no ambition-rousing atmosphere of recognition and applause—Dahomey, for instance. Dahomey could not find an Edison out; in Dahomey an Edison could not find himself out. Broadly speaking, genius is not born with sight, but blind; and it is not itself that opens its eyes, but the subtle influences of a myriad of stimulating exterior circumstances.

We all know this to be not a guess, but a mere commonplace fact, a truism. Lorraine was Joan of Arc’s Dahomey. And there the Riddle confronts us. We can understand how she could be born with military genius, with leonine courage, with incomparable fortitude, with a mind which was in several particulars a prodigy—a mind which included among its specialties the lawyer’s gift of detecting traps laid by the adversary in cunning and treacherous arrangements of seemingly innocent words, the orator’s gift of eloquence, the advocate’s gift of presenting a case in clear and compact form, the judge’s gift of sorting and weighing evidence, and finally, something recognizable as more than a mere trace of the states- man’s gift of understanding a political situation and how to make profitable use of such opportunities as it offers; we can comprehend how she could be born with these great qualities, but we cannot comprehend how they became immediately usable and effective without the developing forces of a sympathetic atmosphere and the training which comes of teaching, study, practice—years of practice,—and the crowning and perfecting help of a thousand mistakes. We can understand how the possibilities of the future perfect peach are all lying hid in the humble bitter-almond, but we cannot conceive of the peach springing directly from the almond without the intervening long seasons of patient cultivation and development. Out of a cattle-pasturing peasant village lost in the remotenesses of an unvisited wilderness and atrophied with ages of stupefaction and ignorance we cannot see a Joan of Arc issue equipped to the last detail for her amazing career and hope to be able to explain the riddle of it, labor at it as we may.

It is beyond us. All the rules fail in this girl’s case. In the world’s history she stands alone—quite alone. Others have been great in their first public exhibitions of generalship, valor, legal talent, diplomacy, fortitude; but always their previous years and associations had been in a larger or smaller degree a preparation for these things. There have been no exceptions to the rule. But Joan was competent in a law case at sixteen without ever having seen a law book or a court-house before; she had no training in soldiership and no associations with it, yet she was a competent general in her first campaign; she was brave in her first battle, yet her courage had had no education—not even the education which a boy’s courage gets from never-ceasing reminders that it is not permissible in a boy to be a coward, but only in a girl; friendless, alone, ignorant, in the blossom of her youth, she sat week after week, a prisoner in chains, before her assemblage of judges, enemies hunting her to her death, the ablest minds in France, and answered them out of an untaught wisdom which overmatched their learning, baffled their tricks and treacheries with a native sagacity which compelled their wonder, and scored every day a victory against these incredible odds and camped unchallenged on the field. In the history of the human intellect, untrained, inexperienced, and using only its birthright equipment of untried capacities, there is nothing which approaches this. Joan of Arc stands alone, and must continue to stand alone, by reason of the unfellowed fact that in the things wherein she was great she was so without shade or suggestion of help from preparatory teaching, practice, environment, or experience. There is no one to compare her with, none to measure her by; for all others among the illustrious grew towards their high place in an atmosphere and surroundings which discovered their gift to them and nourished it and promoted it, intentionally or unconsciously. There have been other young generals, but they were not girls; young generals, but they had been soldiers before they were generals: she began as a general; she commanded the first army she ever saw; she led it from victory to victory, and never lost a battle with it; there have been young commanders-in-chief, but none so young as she: she is the only soldier in history who has held the supreme command of a nation’s armies at the age of seventeen.

Her history has still another feature which sets her apart and leaves her without fellow or competitor: there have been many uninspired prophets, but she was the only one who ever ventured the daring detail of naming, along with a foretold event, the event’s precise nature, the special time-limit within which it would occur, and the place—and scored fulfilment. At Vaucouleurs she said she must go to the King and be made his general, and break the English power, and crown her sovereign—“at Rheims.” It all happened. It was all to happen “next year”—and it did. She foretold her first wound and its character and date a month in advance, and the prophecy was recorded in a public record-book three weeks in advance. She repeated it the morning of the date named, and it was fulfilled before night. At Tours she foretold the limit of her military career—saying it would end in one year from the time of its utterance—and she was right. She foretold her martyrdom—using that word, and naming a time three months away—and again she was right. At a time when France seemed hopelessly and permanently in the hands of the English she twice asserted in her prison before her judges that within seven years the English would meet with a mightier disaster than had been the fall of Orleans: it happened within five—the fall of Paris. Other prophecies of hers came true, both as to the event named and the time-limit prescribed.

She was deeply religious, and believed that she had daily speech with angels; that she saw them face to face, and that they counselled her, comforted and heartened her, and brought commands to her direct from God. She had a childlike faith in the heavenly origin of her apparitions and her Voices, and not any threat of any form of death was able to frighten it out of her loyal heart. She was a beautiful and simple and lovable character. In the records of the Trials this comes out in clear and shining detail. She was gentle and winning and affectionate; she loved her home and friends and her village life; she was miserable in the presence of pain and suffering; she was full of compassion: on the field of her most splendid victory she forgot her triumphs to hold in her lap the head of a dying enemy and comfort his passing spirit with pitying words; in an age when it was common to slaughter prisoners she stood dauntless between hers and harm, and saved them alive; she was forgiving, generous, unselfish, magnanimous; she was pure from all spot or stain of baseness. And always she was a girl; and dear and worshipful, as is meet for that estate: when she fell wounded, the first time, she was frightened, and cried when she saw her blood gushing from her breast; but she was Joan of Arc! and when presently she found that her generals were sounding the retreat, she staggered to her feet and led the assault again and took that place by storm.

There is no blemish in that rounded and beautiful character.

How strange it is!—that almost invariably the artist remembers only one detail—one minor and meaningless detail of the personality of Joan of Arc: to wit, that she was a peasant girl—and forgets all the rest; and so he paints her as a strapping middle-aged fishwoman, with costume to match, and in her face the spirituality of a ham. He is slave to his one idea, and forgets to observe that the supremely great souls are never lodged in gross bodies. No brawn, no muscle, could endure the work that their bodies must do; they do their miracles by the spirit, which has fifty times the strength and staying power of brawn and muscle. The Napoleons are little, not big; and they work twenty hours in the twenty-four, and come up fresh, while the big soldiers with the little hearts faint around them with fatigue. We know what Joan of Arc was like, without asking—merely by what she did. The artist should paint her spirit—then he could not fail to paint her body aright. She would rise before us, then, a vision to win us, not repel: a lithe young slender figure, instinct with “the unbought grace of youth,” dear and bonny and lovable, the face beautiful, and transfigured with the light of that lustrous intellect and the fires of that unquenchable spirit.

Taking into account, as I have suggested before, all the circumstances—her origin, youth, sex, illiteracy, early environment, and the obstructing conditions under which she exploited her high gifts and made her conquests in the field and before the courts that tried her for her life,—she is easily and by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

.jpg)

Multatuli

(1820-1887)

Ideën (7 delen, 1862-1877)

Idee Nr. 41

Ik leg me toe op ‘t schryven van levend Hollands. Maar ik heb schoolgegaan.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

XV. A maïtre François Villon

Je me figure, ô vieux maître, ton visage exsangue, coiffé d’un galeux bicoquet; je me figure ton ventre vague, tes longs bras osseux, tes jambes héronnières enroulées de bas d’un rose louche, étoilés de déchirures, papelonnés d’écailles de boue.

Je crois te voir, ô Villon, l’hiver, alors que le glas fourre d’hermine les toits des maisons, errer dans les rues de Paris, famélique, hagard, grelottant, en arrêt devant les marchands de beuverie, caressant, de convoiteux regards, la panse monacale des bouteilles.

Je crois te voir, exténué de fatigue, las de misère, te tapir dans un des repaires de la cour des Miracles, pour échapper aux archers du guet, et là, seul dans un coin, ouvrir, loin de tous, le merveilleux écrin de ton génie.

Quel magique ruissellement de pierres! Quel étrange fourmillement de feux! Quelles étonnantes cassures d’étoffes rudes et rousses! Quelles folles striures de couleurs vives et mornes! Et quand ton oeuvre était finie, quand ta ballade était tissée et se déroulait, irisée de tons éclatants, sertie de diamants et de trivials cailloux, qui en faisaient mieux ressortir encore la limpidité sereine, tu te sentais grand, incomparable, l’égal d’un dieu, et puis tu retombais à néant, la faim te tordait les entrailles, et tu devenais le vulgaire tire-laine, l’ignominieux amant de la grosse Margot!

Tu détroussais le passant, on te jetait dans un cul de basse-fosse, et, là-bas, enterré, plié en deux, crevant de faim, tu criais grâce, pitié! tu appelais à l’aide tes compaings de galles, les francs-gaultiers, les ribleurs, les coquillarts, les marmonneux, les cagnardiers!

Le laisserez là, le povre Villon! Allons, madones d’amour qu’il a chantées, hahay! Margot, Rose, Jehanne la Saulcissière, hahay! Guillemette, Marion la Peau-tarde, hahay! la petite Macée, hahay! toute la folle quenaille des ribaudes, des truandes, des grivoises, des raillardes, des villotières! Excitez les hommes, réveillez les biberons, entraînez-les au secours de leur chef, le poète Villon!

Las! Les fossés sont profonds, les tours sont hautes, les piques des haquebutiers sont aiguës, le vin coule, la cervoise pétille, le feu flambe, les filles sont gorgées de hideuses saouleries: ô pauvre Villon, personne ne bouge!

Claque des dents, meurtris tes mains, guermente-toi, pleure d’angoisseux gémissements, tes amis ne t’écoutent pas; ils sont à la taverne, sous les tresteaux, ivres d’hypocras, crevés de mangeailles, inertes, débraillés, fétides, couchés les uns sur les autres, Frémin l’Etourdi sur le bon Jehan Cotard qui se rigole encore et remue les badigoinces, Michault Cul d’Oue sur ce gros lippu de Beaulde. Tes maîtresses se moquent bien de toi! elles sont dans les bouges de la Cité qui s’ébattent avec les escoliers et les soudards. Le cerveau atteint du mal de pique, le nez grafiné de horions, elles frottent leur rouge museau sur les joues des buveurs et se rincent galantement la fale!

Oh! tu es seul et bien seul! Meurs donc, larron; crève donc dans ta fosse, souteneur de gouges; tu n’en seras pas moins immortel, poète grandiosement fangeux, ciseleur inimitable du vers, joaillier non pareil de la ballade!

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Huysmans, J.-K.

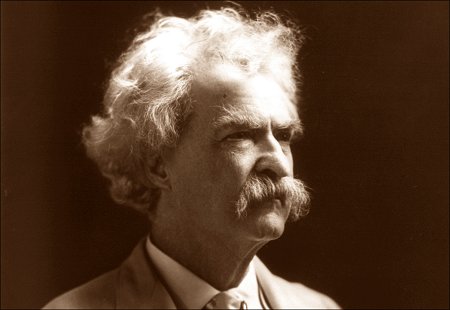

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

A Helpless Situation

Once or twice a year I get a letter of a certain pattern, a pattern that never materially changes, in form and substance, yet I cannot get used to that letter—it always astonishes me. It affects me as the locomotive always affects me: I say to myself, “I have seen you a thousand times, you always look the same way, yet you are always a wonder, and you are always impossible; to contrive you is clearly beyond human genius—you can’t exist, you don’t exist, yet here you are!”

I have a letter of that kind by me, a very old one. I yearn to print it, and where is the harm? The writer of it is dead years ago, no doubt, and if I conceal her name and address—her this-world address—I am sure her shade will not mind. And with it I wish to print the answer which I wrote at the time but probably did not send. If it went—which is not likely—it went in the form of a copy, for I find the original still here, pigeon-holed with the said letter. To that kind of letters we all write answers which we do not send, fearing to hurt where we have no desire to hurt; I have done it many a time, and this is doubtless a case of the sort.

The Letter

X——., California, June 3, 1879.

Mr. S. L. Clemens, Hartford, Conn.:

Dear Sir,—You will doubtless be surprised to know who has presumed to write and ask a favor of you. Let your memory go back to your days in the Humboldt mines—’62-’63. You will remember, you and Clagett and Oliver and the old blacksmith Tillou lived in a lean-to which was half-way up the gulch, and there were six log cabins in the camp—strung pretty well separated up the gulch from its mouth at the desert to where the last claim was, at the divide. The lean-to you lived in was the one with a canvas roof that the cow fell down through one night, as told about by you in Roughing It—my uncle Simmons remembers it very well. He lived in the principal cabin, half-way up the divide, along with Dixon and Parker and Smith. It had two rooms, one for kitchen and the other for bunks, and was the only one that had. You and your party were there on the great night, the time they had dried-apple-pie, Uncle Simmons often speaks of it. It seems curious that dried-apple-pie should have seemed such a great thing, but it was, and it shows how far Humboldt was out of the world and difficult to get to, and how slim the regular bill of fare was. Sixteen years ago—it is a long time. I was a little girl then, only fourteen. I never saw you, I lived in Washoe. But Uncle Simmons ran across you every now and then, all during those weeks that you and party were there working your claim which was like the rest. The camp played out long and long ago, there wasn’t silver enough in it to make a button. You never saw my husband, but he was there after you left, and lived in that very lean-to, a bachelor then but married to me now. He often wishes there had been a photographer there in those days, he would have taken the lean-to. He got hurt in the old Hal Clayton claim that was abandoned like the others, putting in a blast and not climbing out quick enough, though he scrambled the best he could. It landed him clear down on the trail and hit a Piute. For weeks they thought he would not get over it but he did, and is all right, now. Has been ever since. This is a long introduction but it is the only way I can make myself known. The favor I ask I feel assured your generous heart will grant: Give me some advice about a book I have written. I do not claim anything for it only it is mostly true and as interesting as most of the books of the times. I am unknown in the literary world and you know what that means unless one has some one of influence (like yourself) to help you by speaking a good word for you. I would like to place the book on royalty basis plan with any one you would suggest.

This is a secret from my husband and family. I intend it as a surprise in case I get it published.

Feeling you will take an interest in this and if possible write me a letter to some publisher, or, better still, if you could see them for me and then let me hear.

I appeal to you to grant me this favor. With deepest gratitude I thank you for your attention.

One knows, without inquiring, that the twin of that embarrassing letter is forever and ever flying in this and that and the other direction across the continent in the mails, daily, nightly, hourly, unceasingly, unrestingly. It goes to every well-known merchant, and railway official, and manufacturer, and capitalist, and Mayor, and Congressman, and Governor, and editor, and publisher, and author, and broker, and banker—in a word, to every person who is supposed to have “influence.” It always follows the one pattern: “You do not know me, but you once knew a relative of mine,” etc., etc. We should all like to help the applicants, we should all be glad to do it, we should all like to return the sort of answer that is desired, but—Well, there is not a thing we can do that would be a help, for not in any instance does that letter ever come from any one who can be helped. The struggler whom you could help does his own helping; it would not occur to him to apply to you, a stranger. He has talent and knows it, and he goes into his fight eagerly and with energy and determination—all alone, preferring to be alone. That pathetic letter which comes to you from the incapable, the unhelpable—how do you who are familiar with it answer it? What do you find to say? You do not want to inflict a wound; you hunt ways to avoid that. What do you find? How do you get out of your hard place with a contented conscience? Do you try to explain? The old reply of mine to such a letter shows that I tried that once. Was I satisfied with the result? Possibly; and possibly not; probably not; almost certainly not. I have long ago forgotten all about it. But, anyway, I append my effort:

The Reply

I know Mr. H., and I will go to him, dear madam, if upon reflection you find you still desire it. There will be a conversation. I know the form it will take. It will be like this:

Mr. H. How do her books strike you?

Mr. Clemens. I am not acquainted with them.

H. Who has been her publisher?

C. I don’t know.

H. She has one, I suppose?

C. I—I think not.

H. Ah. You think this is her first book?

C. Yes—I suppose so. I think so.

H. What is it about? What is the character of it?

C. I believe I do not know.

H. Have you seen it?

C. Well—no, I haven’t.

H. Ah-h. How long have you known her?

C. I don’t know her.

H. Don’t know her?

C. No.

H. Ah-h. How did you come to be interested in her book, then?

C. Well, she—she wrote and asked me to find a publisher for her, and mentioned you.

H. Why should she apply to you instead of to me?

C. She wished me to use my influence.

H. Dear me, what has influence to do with such a matter?

C. Well, I think she thought you would be more likely to examine her book if you were influenced.

H. Why, what we are here for is to examine books—anybody’s book that comes along. It’s our business. Why should we turn away a book unexamined because it’s a stranger’s? It would be foolish. No publisher does it. On what ground did she request your influence, since you do not know her? She must have thought you knew her literature and could speak for it. Is that it?

C. No; she knew I didn’t.

H. Well, what then? She had a reason of some sort for believing you competent to recommend her literature, and also under obligations to do it?

C. Yes, I—I knew her uncle.

H. Knew her uncle?

C. Yes.

H. Upon my word! So, you knew her uncle; her uncle knows her literature; he endorses it to you; the chain is complete, nothing further needed; you are satisfied, and therefore—

C. No, that isn’t all, there are other ties. I knew the cabin her uncle lived in, in the mines; I knew his partners, too; also I came near knowing her husband before she married him, and I did know the abandoned shaft where a premature blast went off and he went flying through the air and clear down to the trail and hit an Indian in the back with almost fatal consequences.

H. To him, or to the Indian?

C. She didn’t say which it was.

H. (With a sigh.) It certainly beats the band! You don’t know her, you don’t know her literature, you don’t know who got hurt when the blast went off, you don’t know a single thing for us to build an estimate of her book upon, so far as I—

C. I knew her uncle. You are forgetting her uncle.

H. Oh, what use is he? Did you know him long? How long was it?

C. Well, I don’t know that I really knew him, but I must have met him, anyway. I think it was that way; you can’t tell about these things, you know, except when they are recent.

H. Recent? When was all this?

C. Sixteen years ago.

H. What a basis to judge a book upon! At first you said you knew him, and now you don’t know whether you did or not.

C. Oh yes, I knew him; anyway, I think I thought I did; I’m perfectly certain of it.

H. What makes you think you thought you knew him?

C. Why, she says I did, herself.

H. She says so!

C. Yes, she does, and I did know him, too, though I don’t remember it now.

H. Come—how can you know it when you don’t remember it.

C. I don’t know. That is, I don’t know the process, but I do know lots of things that I don’t remember, and remember lots of things that I don’t know. It’s so with every educated person.

H. (After a pause.) Is your time valuable?

C. No—well, not very.

H. Mine is.

So I came away then, because he was looking tired. Overwork, I reckon; I never do that; I have seen the evil effects of it. My mother was always afraid I would overwork myself, but I never did.

Dear madam, you see how it would happen if I went there. He would ask me those questions, and I would try to answer them to suit him, and he would hunt me here and there and yonder and get me embarrassed more and more all the time, and at last he would look tired on account of overwork, and there it would end and nothing done. I wish I could be useful to you, but, you see, they do not care for uncles or any of those things; it doesn’t move them, it doesn’t have the least effect, they don’t care for anything but the literature itself, and they as good as despise influence. But they do care for books, and are eager to get them and examine them, no matter whence they come, nor from whose pen. If you will send yours to a publisher—any publisher—he will certainly examine it, I can assure you of that.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

.jpg)

Ton van Reen

BENZINE

Een lucht van benzine hangt over het dorp

de dreiging zit dik in de kelen van de mensen

zomaar een enkele vonk van haat

kan een ontploffing veroorzaken

en het vuur over de daken laten dansen

Oproer stinkt altijd naar benzine

die ontploft, door klappende handen

of door de kreet van een kind

In de haard van de angst

ruikt het altijd naar benzine

die als een giftige slang over straat vloeit

wachtend op die ene vonk van haat

die de vlammen als een leger ratten

over de daken van het dorp laat rennen

Geweld ruikt altijd naar benzine

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -De naam van het mes, Reen, Ton van

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

XIV. La rive gauche

Las du bruissement des foules, dégoûté des criailleries des histrionnes d’amour, je vais me promener sur le boulevard Montparnasse; je gagne la rue de la Santé, la rue du Pot-au-Lait et les chemins vagues qui longent la Bièvre. Cette petite rivière, si bleue à Buc, est d’un noir de suie à Paris. Quelquefois même elle exhale des relents de bourbe et de vieux cuir, mais elle est presque toujours bordée de deux bandes de hauts peupliers et encadrée d’aspects bizarrement tristes qui évoquent en moi comme de lointains souvenirs, ou comme les rythmes désolés de la musique de Schubert. Quelle rue étrange que cette rue du Pot-au-Lait! déserte, étranglée, descendant par une pente rapide dans une grande voie inhabitée, aux pavés enchâssés dans la boue; le ruisseau court au milieu de la rue et charrie dans ses petites cascades des îlots d’épluchures de légumes qui tigrent de vert les eaux noirâtres. Les maisons qui la bordent s’appuient et se serrent les unes contre les autres. Les volets sont fermés; les portes closes sont émaillées de gros clous, et parfois un peuple de petits galopins, au nez sale, aux cheveux frisés, se traînent sur les genoux, malgré les observations de leurs mères et jouent une longue partie de billes. Il faut les voir, accroupis, montrant leur petite culotte rapiécée, du fond de laquelle s’échappe un drapeau blanc, s’appuyant de la main gauche à terre et lançant dans un gros trou une petite bille. Ils se relèvent, sautillent, poussent des cris de joie, tandis que le partner, un petit bambin aussi mal accoutré, fait une mine boudeuse et observe avec inquiétude l’adresse de son adversaire. Une lanterne, suspendue en l’air par des cordes accrochées à deux maisons qui se font face, éclaire la rue, le soir. Il y a quelque temps, ces cordes se rompirent et le réverbère fut rattaché par mille petites ficelles qui aidèrent les grosses cordes à en soutenir le poids. On eût dit de la lanterne, au milieu de ce treillis de cordelettes, une gigantesque araignée tissant sa toile. Une fois engagé dans la longue route qui rejoint cette ruelle, vous arrivez, après quelques minutes de marche, près d’un petit étang, moiré de follicules vertes. On croirait être devant un étrange gazon, si parfois des grenouilles ne sautaient des herbes et ne faisaient clapoter et rejaillir sur le feuillage des gouttelettes d’eau brune.

La vue est bornée. D’un côté, la Bièvre et une rangée d’ormes et de peupliers; de l’autre, les remparts. Des linges bariolés qui sèchent sur lune corde, un âne qui remue les oreilles et se bat les flancs de sa queue pour chasser les mouches; un peu plus loin, une hutte de sauvage, bâtie avec quelques lattes, crépie de mortier, coiffée d’un bonnet de chaume, percée d’un tuyau pour laisser échapper la fumée: c’est tout. C’est navrant, et pourtant cette solitude ne manque pas de charme. Ce n’est pas la campagne des environs de Paris, polluée par les ébats des courtauds de boutique, ces bois qui regorgent de monde, le dimanche, et dont les taillis sont semés de papiers gras et de culs de bouteilles; ce n’est pas la vraie campagne, si verte, si rieuse au clair soleil; c’est un monde à part, triste, aride, mais par cela même solitaire et charmant. Quelques ouvriers ou quelques femmes qui passent, un panier au bras, à la main un enfant qui se fait traîner et traîne lui-même un petit chariot en bois, peint en bleu, avec des roues jaunes, rompent seuls la monotonie de la route. Parfois, le dimanche, devant un petit cabaret dont l’auvent est festonné de pampres d’un vert cru et de gros raisins bleus, une famille de jongleurs vient donner des représentations en face des buveurs attablés en dehors. J’en vis une fois trois, tous jeunes, et une fille, au teint couleur d’ambre, aux grands yeux effarés, noirs comme des obsidiennes. Ils avaient établi une corde frottée de craie, reposant sur deux poteaux en forme d’X. Un drôle, à la face lamentablement laide, tournait pendant ce temps la bobinette d’un orgue. De tous côtés je voyais courir des enfants; ils arrivaient tout en sueur, se rangeaient en cercle et attendaient avec une visible impatience le commencement des exercices. Les saltimbanques furent bientôt prêts : ils se ceignirent le front d’une bandelette rose, lamée de papillons de cuivre, firent craquer leurs jointures et s’élancèrent sur la corde.

Ils débutaient dans le métier et, après quelques tordions, ils s’épatèrent sur les pavés au risque de se rompre les os. La foule s’esbaudit. Un pauvre petit diable qui était tombé se releva avec peine, en se frottant le râble. Il souffrait atrocement et, malgré d’héroïques efforts, deux grosses larmes lui jaillirent des yeux et coulèrent sur ses joues. Ses frères le rebutèrent et sa soeur se mit a rire et lui tourna le dos.