Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Le voyage de Hollande verscheen op 12 februari 1964 bij de Franse uitgever Seghers. De editie (2025 exemplaren!) werd verfraaid met een tekening van Jongkind, een typisch Hollands landschap met windmolens, beemden en scheepjes onder een lage wolkenlucht.

Al in 1965 verscheen een herdruk, daarna werd de bundel opnieuw uitgegeven in 1981 en 2005, telkens bij Seghers. In 2007 ten slotte werd Le voyage de Hollande in de Bibliothèque de la Pléiade opgenomen als onderdeel van Aragons volledige dichtwerk (OEuvres poétiques complètes, deel II, Parijs, Gallimard).

Al in 1965 verscheen een herdruk, daarna werd de bundel opnieuw uitgegeven in 1981 en 2005, telkens bij Seghers. In 2007 ten slotte werd Le voyage de Hollande in de Bibliothèque de la Pléiade opgenomen als onderdeel van Aragons volledige dichtwerk (OEuvres poétiques complètes, deel II, Parijs, Gallimard).

In de zomer van 1963 verbleven Louis Aragon (1897-1982) en zijn vrouw Elsa Triolet (1896-1970) een maand in Nederland. Tussen 29 juli en 26 augustus bezochten ze onder meer Texel, Zuid-Holland (Wassenaar) en Utrecht.

De neerslag van die reis vinden we terug in Le voyage de Hollande, een bundel bestaande uit zes delen van wisselende lengte (twee tot twaalf gedichten), voorafgegaan door een kwatrijn waarin de lezer wordt aangemaand nooit de liefde in opspraak te brengen: wie dat doet mag het ‘domein’ van de dichter niet betreden. Een domein dat ten dele reëel is, geïnspireerd door het verblijf in Nederland, ten dele utopie van de liefde en ode aan de geliefde.

Louis Aragon

De Hollandse reis

2019

Vertaling: Katelijne De Vuyst

Tweetalige bundel

Uitgeverij Vleugels

Franse reeks

isbn 978 90 78627 67 8

128 pagina’s

€ 23,50

# new books

Louis Aragon

De Hollandse reis

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, SURREALISM, Surrealism, Surrealisme

Stil luistert hij naar de zangerige stem van de juf. Luisterend naar de beschrijving van de duivel, die er in zijn nette pak nog deftiger uitzag dan de burgemeester, droomt Mels weg.

Zijn hoofd zakt op de klep van zijn lessenaar. Vaag ziet hij de bloemen op de vensterbank. De juf kweekt ze zelf. De bloemen die nog geen naam hebben, geeft ze namen van de meisjes in de klas. Alina is een plant die Mels ook kent als wilde aardbei.

Zijn hoofd zakt op de klep van zijn lessenaar. Vaag ziet hij de bloemen op de vensterbank. De juf kweekt ze zelf. De bloemen die nog geen naam hebben, geeft ze namen van de meisjes in de klas. Alina is een plant die Mels ook kent als wilde aardbei.

`Niet’, zegt de juf.

`Wel’, zegt Mels.

Melanie lijkt op een vergeet-mij-niet maar is het niet.

De bloem die naar Thija is genoemd is een wild viooltje met gele blaadjes. Lizet is een snijgeranium. Micha is een roos in een nieuwe kleur rood.

Door het vertellen wordt de klas om hem heen een grote ballon die uit het dorp opstijgt en, net als de zeppelin die ze pas hebben gezien, over de Wijer weg zweeft.

Hij ziet zichzelf kleiner worden, tot hij tussen de wolken zweeft en hij er nog alleen maar, hand in hand, in zit met Thija. Ze draagt een lange rok die tot over haar schoenen hangt en ze heeft een strik in het haar die zo groot is dat ze onder zijn neus kriebelt als ze zich naar hem toe buigt.

Precies zoals op de dag van haar vertrek.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (107)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

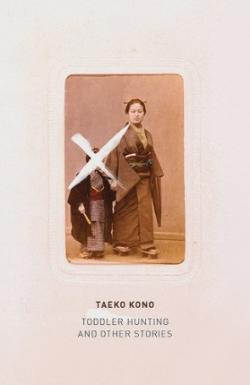

Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories introduces a startlingly original voice. Winner of Japan’s top literary prizes for fiction (among them the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri), Taeko Kono writes with a strange beauty, pinpricked with sadomasochistic and disquieting scenes.

In the title story, the protagonist loathes young girls, but compulsively buys expensive clothes for little boys so that she can watch them dress and undress. The impersonal gaze Taeko Kono turns on this behavior transfixes the reader with a fatal question: What are we hunting for? And why?

In the title story, the protagonist loathes young girls, but compulsively buys expensive clothes for little boys so that she can watch them dress and undress. The impersonal gaze Taeko Kono turns on this behavior transfixes the reader with a fatal question: What are we hunting for? And why?

Multiplying perspectives and refracting light from the strangely facing mirrors of fantasy and reality, pain and pleasure, these ten stories present Kono at her very best.

Winner of Japan’s top literary prizes (the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri), Taeko Kono writes with a strange beauty: her tales are pinpricked with disquieting scenes, her characters all teetering on self-dissolution, especially in the context of their intimate relationships. In the title story, the protagonist loathes young girls but compulsively buys expensive clothes for little boys so that she can watch them dress and undress. Taeko Kono’s detached gaze at this alarming behavior transfixes the reader: What are we hunting for? And why? Multiplying perspectives and refracting light from the facing mirrors of fantasy and reality, pain and pleasure, Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories presents a major Japanese writer at her very best.

Toddler Hunting: And Other Stories

Taeko Kono

Publisher: New Directions Publishing Corporation

Publication date: Nov. 2018

Publication country:United States

Paperback

Pages:272

ISBN: 978-0-81122-827-5

17.00 €

# More books

Taeko Kono

Fiction

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive K-L

Met haar succesdebuut Habitus wint Radna Fabias na de C. Buddingh’-prijs 2018 en de Awater Poëzieprijs en Herman De Coninckprijs 2019 óók deze eerste editie van De Grote Poëzieprijs.

De prijs, € 25.000,- voor de beste Nederlandstalige bundel van het jaar, werd op de slotdag van het gouden Poetry International Festival uitgereikt samen met de C. Buddingh’-prijs, die naar Roberta Petzoldt ging, voor haar debuut Vruchtwatervuurlinie’. Habitus is daarmee zonder meer de meest prijswinnende debuutbundel ooit.

Ook werden op het festival prijzen uitgereikt door jongeren, een initiatief van School der Poëzie.

De School der Poëzie-Communityprijs ging naar Ted van Lieshout voor Ze gaan er met je neus vandoor,

Roelof ten Napel kreeg de Jongerenprijs voor Het woedeboek waarmee hij ook kans maakte op De Grote Poëzieprijs én de C. Buddingh’-prijs. Met het uitreikingsprogramma ‘Prijs de poëzie!’ sloot Poetry International het gouden jubileumfestival even feestelijk af als dat het begon.

De Grote Poëzieprijs voor Radna Fabias

De Grote Poëzieprijs is dé prijs voor Nederlandstalige poëzie en bekroont de beste Nederlandstalige bundel van het jaar met € 25.000,-.

De Grote Poëzieprijs is dé prijs voor Nederlandstalige poëzie en bekroont de beste Nederlandstalige bundel van het jaar met € 25.000,-.

De jury van De Grote Poëzieprijs 2019 kreeg 150 bundels ter lezing en nomineerde er niet vijf maar zes, vanwege het hoge aantal inzendingen, de verlengde periode waarover werd gejureerd en de aangetroffen kwaliteit.

Opnieuw gaat de hoofdprijs dus naar Radna Fabias: “Fabias graaft net zo lang in wat bedenkelijk is – waarbij ze ook zichzelf niet spaart – totdat de complexiteit van een probleem zich openbaart.

Dit maakt dat Habitus (Arbeiderspers) deelneemt aan het ‘gesprek van de dag’, maar tegelijk – en belangrijker – dat de bundel er ook een krachtig tegengif tegen is.

Niets is eenvoudig in deze bundel, niets is op te lossen met een paar slimme oneliners of standpunten. Fabias maakt het persoonlijke politiek en het politieke persoonlijk,” oordeelde de jury.

De C. Buddingh’-prijs voor Roberta Petzoldt

De prijs voor beste Nederlandstalige poëziedebuut – jaarlijks uitgereikt op het Poetry International Festival – gaat dit jaar naar Roberta Petzoldt.

De prijs voor beste Nederlandstalige poëziedebuut – jaarlijks uitgereikt op het Poetry International Festival – gaat dit jaar naar Roberta Petzoldt.

Haar debuut Vruchtwatervuurlinie (Van Oorschot) gaat over verlies en is strijdbaar, humoristisch, prikkelend en fel maar boven alles een rigoureus allerindividueelst onderzoek waarbij de dichter, sneller dan de eigen schaduw, de poëzie zelf op de staart probeert te trappen of ‘zonder vliegtuig de wolken raken / bewegen door / een getraind gevoel voor humor / en een eenzame logica’.

Op intieme wijze creëert de dichter een verrassend nieuw poëtisch universum, wat weergaloze gedichten en tijdloze regels oplevert: ‘ik weet dat mensen op hun honden lijken, maar jij / lijkt op de hond van iemand anders’”, aldus de jury.

Jongerenprijzen bij De Grote Poëzieprijs

School der Poëzie reikte op de slotavond van Poetry International twee prijzen uit namens de Poëzie Community en namens scholieren uit Nederland en Vlaanderen.

School der Poëzie reikte op de slotavond van Poetry International twee prijzen uit namens de Poëzie Community en namens scholieren uit Nederland en Vlaanderen.

De Poëzie Community van School der Poëzie koos unaniem voor Ze gaan er met je neus vandoor (Leopold) van Ted van Lieshout, omdat het “een avontuur was om te lezen.” Jongeren van scholen uit Antwerpen, Amsterdam, Rotterdam en Gent namen deel aan workshops van School der Poëzie en lieten zich inspireren door de gedichten van de zes genomineerden. Zij kenden hun Jongerenprijs toe aan Roelof ten Napel voor Het woedeboek (Hollands Diep) “omdat het over woede gaat én over liefde.”

De jury van De Grote Poëzieprijs bestond uit Joost Baars, Yra van Dijk, Adriaan van Dis, Cindy Kerseborn en Maud Vanhauwaert.

De jury van De Grote Poëzieprijs bestond uit Joost Baars, Yra van Dijk, Adriaan van Dis, Cindy Kerseborn en Maud Vanhauwaert.

Zij nomineerden naast Habitus van Radna Fabias ook Nachtboot van Maria Barnas, Stalker van Joost Decorte, Het woedeboek van Roelof ten Napel, Genadeklap van Willem Jan Otten en Onze kinderjaren van Xavier Roelens. De jury van de C. Buddingh’-prijs bestond uit Els Moors, Tsead Bruinja en Kila van der Starre. Zij nomineerden ook Obelisque van Obe Alkema, Dwaallichten van Gerda Blees en Het woedeboek van Roelof ten Napel.

Eerste Grote Poëzieprijs voor Radna Fabias

Roberta Petzoldt wint ‘de Buddingh’

Jongerenprijzen voor Ted van Lieshout en Roelof ten Napel

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, #More Poetry Archives, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive E-F, Archive E-F, Archive K-L, Archive M-N, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, Lieshout, Ted van, Poetry International

In 2019 jubileert Lustwarande. Delirious is de tiende expositie in De Oude Warande en de zesde overzichtseditie, met voor het merendeel nieuwe werken van vijfentwintig internationale kunstenaars.

Delirious

Jubileumeditie

15 juni – 20 oktober 2019

Opening: zaterdag 15 juni om 14.00

Evenals voorgaande overzichtsedities van Lustwarande presenteert Delirious recente ontwikkelingen in de hedendaagse sculptuur. Die recente ontwikkelingen worden gekenschetst door grote diversiteit. Naast reflecties op actuele thema’s (vloeiende identiteit, migratie, wetenschappelijke innovaties, het veranderende besef over de verhouding tussen mens en natuur, de hyperversnelling van het alledaagse leven als gevolg van nieuwe technologieën en psychologische reacties hierop) is de nadruk die er op materiaal gelegd wordt onmiskenbaar en uiterst opmerkelijk. Dit is voor een groot deel het gevolg van de sterke focus op nieuwe denkmodellen die de laatste jaren in het beeldende kunstdiscours waarneembaar is.

Evenals voorgaande overzichtsedities van Lustwarande presenteert Delirious recente ontwikkelingen in de hedendaagse sculptuur. Die recente ontwikkelingen worden gekenschetst door grote diversiteit. Naast reflecties op actuele thema’s (vloeiende identiteit, migratie, wetenschappelijke innovaties, het veranderende besef over de verhouding tussen mens en natuur, de hyperversnelling van het alledaagse leven als gevolg van nieuwe technologieën en psychologische reacties hierop) is de nadruk die er op materiaal gelegd wordt onmiskenbaar en uiterst opmerkelijk. Dit is voor een groot deel het gevolg van de sterke focus op nieuwe denkmodellen die de laatste jaren in het beeldende kunstdiscours waarneembaar is.

Het is niet verwonderlijk dat dergelijke denkkaders directe invloed hebben op de hedendaagse kunstproductie. De onophoudelijke nadruk die er op het belang van materie gelegd wordt heeft ertoe geleid dat een nieuwe generatie kunstenaars de oude filosofische vraag weer op de voorgrond gesteld heeft hoe materie ons beïnvloed en hoe wij materie beïnvloeden. In de context van voortschrijdende technologie, toenemende digitalisering, alles nivellerende globalisering en noodzakelijke herdefiniëring van ons wereldbeeld, is er hernieuwde aandacht voor de fysieke productie van beelden en voor heronderzoek naar bestaande en nieuwe materialen. Net als midden jaren ’80 van de vorige eeuw staat de huid van sculptuur opnieuw centraal, ditmaal echter in een niet eerder vertoonde mix van combinaties. Metalen, plastic, nieuwe kunststoffen, 3D prints, aarde, pigmenten, textiel, glas, klei, – en terug van weggeweest – hout en marmer en andere steensoorten en gevonden voorwerpen worden scrupuleus geassembleerd en gebricoleerd, veelal met een conceptuele inslag.

Dit vloeit niet alleen rechtstreeks voort uit bovengeschetste nieuwe theoretische modellen maar ook uit de fundamenteel veranderde eigenschappen van de hedendaagse beeldcultuur, die bijna vloeiend geworden is, uit de toenemende huidige mengmogelijkheden en uit de drang om die zowel digitaal als fysiek verder te onderzoeken, wat gepaard gaat met de noodzaak alle mogelijkheden opnieuw onder de loep te nemen, fysiek en ideologisch. En niet in de laatste plaats doordat kunstenaars een toenemende neiging ervaren zich van het beeldscherm af te wenden om weer in contact te komen met fysieke materialen. Of de kunstenaar het werk eigenhandig maakt of uitbesteedt aan producenten is daarbij van geen belang. De titel Delirious verwijst naar deze hang naar een hernieuwde fysieke sculptuurpraktijk, die zowel ongebreideld euforisch is als ook kritisch reflecterend.

Dit vloeit niet alleen rechtstreeks voort uit bovengeschetste nieuwe theoretische modellen maar ook uit de fundamenteel veranderde eigenschappen van de hedendaagse beeldcultuur, die bijna vloeiend geworden is, uit de toenemende huidige mengmogelijkheden en uit de drang om die zowel digitaal als fysiek verder te onderzoeken, wat gepaard gaat met de noodzaak alle mogelijkheden opnieuw onder de loep te nemen, fysiek en ideologisch. En niet in de laatste plaats doordat kunstenaars een toenemende neiging ervaren zich van het beeldscherm af te wenden om weer in contact te komen met fysieke materialen. Of de kunstenaar het werk eigenhandig maakt of uitbesteedt aan producenten is daarbij van geen belang. De titel Delirious verwijst naar deze hang naar een hernieuwde fysieke sculptuurpraktijk, die zowel ongebreideld euforisch is als ook kritisch reflecterend.

Deelnemende kunstenaars

Isabelle Andriessen (NL)

Nina Canell (SE)

Steven Claydon (UK)

Claudia Comte (CH)

Morgan Courtois (FR)

Hadrien Gerenton (FR)

Daiga Grantina (LV)

Siobhán Hapaska (IR)

Lena Henke (DE)

Camille Henrot (FR)

Nicholas Hlobo (SA)

Saskia Noor van Imhoff (NL)

Sven ’t Jolle (BE)

Sonia Kacem (CH)

Esther Kläs (DE)

Sarah Lucas (UK)

Justin Matherly (US)

Win McCarthy (US)

Bettina Pousttchi (DE)

Magali Reus (NL)

Jehoshua Rozenman (IL/NL)

Bojan Šarčević (FR)

Grace Schwindt (DE)

Eric Sidner (US)

Filip Vervaet (BE)

Publicatie

Publicatie

DELIRIOUS LUSTWARANDE – EXCURSIONS IN CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURE III

Ter gelegenheid van Delirious geeft Lustwarande in dit jubileumjaar de publicatie DELIRIOUS LUSTWARANDE – EXCURSIONS IN CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURE III uit. Naast documentatie van de werken in deze expositie wordt tevens documentatie van alle werken in de voorgaande vier edities (Hybrids (2018), Disruption (2017), Luster (2016) en Rapture & Pain (2015)) opgenomen. De vijf exposities samen geven een helder beeld van de stand van zaken in de hedendaagse sculptuur.

Om de exposities en de werken van een bredere context te voorzien, heeft Lustwarande drie auteurs uitgenodigd om speciaal voor deze publicatie een essay te schrijven: Dominic van den Boogerd, kunstcriticus en coördinator artistieke begeleiding en research bij De Ateliers, Amsterdam, Johan Pas, kunsthistoricus, auteur en hoofd Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen, Domeniek Ruyters, kunsthistoricus en editor in chief Metropolis M, Utrecht

Locatie: park De Oude Warande

Bredaseweg 441

Tilburg

•Chris Driessen

artistiek directeur

•Heidi van Mierlo

zakelijk directeur

# meer informatie website lustwarande

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, Art Criticism, Dutch Landscapes, Exhibition Archive, Fundament - Lustwarande, Sculpture

`Ken jij dat verhaal nog, over die koopman?’ vraagt Mels. `Het verhaal dat de juf voorlas?’

`Ik ken het nog’, zegt Tijger. `Het verhaal van de man in het zwart, die als een koopman langs de huizen ging. Als de mensen aan de deuren kwamen, lichtte hij zijn hoed, zodat ze de horentjes op zijn hoofd zagen.

`Ik ken het nog’, zegt Tijger. `Het verhaal van de man in het zwart, die als een koopman langs de huizen ging. Als de mensen aan de deuren kwamen, lichtte hij zijn hoed, zodat ze de horentjes op zijn hoofd zagen.

Niemand durfde de duivel te weigeren iets van hem te kopen. Maar wat hij te koop aanbood, maakte hen bang. Het waren lege zakken, lege dozen en holle vaten met niks erin. Voor veel geld had je niks gekocht. De duivel verkocht alleen maar lucht. Daar betaalden de mensen voor, uit angst door hem te worden meegenomen. De duivel was de patroon van de kooplui, hun leermeester en hun voorbeeld.’

`Precies, zo ging dat verhaal’, zegt Mels. `Vroeger kende ik het vanbuiten.’

`Daarin was jij beter’, geeft Tijger toe. `Je had een open oor voor verhalen. Maar met sporten was ik beter. Ik heb vaak van je gewonnen.’

`Je kon niet tegen je verlies. Erger was dat je altijd beloond wilde worden. Mijn zakmes, mijn vulpen, jij pikte het allemaal in.’

`Kleine dingen maar. Weet je nog dat we onder de brug door voeren en Lizet op de brug stond. Weet je dat ik je bij de volgende overwinning de kousenband van Lizet had willen vragen?’

`Daar was ik nooit op ingegaan’, zegt Mels een beetje driftig. `Ik kon Lizet niet uitstaan.’

`Je kon je ogen niet van haar afhouden.’

`Hou op.’

`Ik vind het niet gek dat je met haar getrouwd bent.’

`En Thija?’

`Nu denk ik dat het ook een wedstrijd was.’

`Voor jou?’

`Ja, zeker voor mij.’

`En jij zou hebben gewonnen?’

`Ik won toch altijd alles?’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (106)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

How far would you run to escape your life?

Anita lives in Karachi’s biggest slum. Her mother is a maalish wali, paid to massage the tired bones of rich women. But Anita’s life will change forever when she meets her elderly neighbour, a man whose shelves of books promise an escape to a different world.

On the other side of Karachi lives Monty, whose father owns half the city and expects great things of him. But when a beautiful and rebellious girl joins his school, Monty will find his life going in a very different direction.

On the other side of Karachi lives Monty, whose father owns half the city and expects great things of him. But when a beautiful and rebellious girl joins his school, Monty will find his life going in a very different direction.

Sunny’s father left India and went to England to give his son the opportunities he never had. Yet Sunny doesn’t fit in anywhere. It’s only when his charismatic cousin comes back into his life that he realises his life could hold more possibilities than he ever imagined.

These three lives will cross in the desert, a place where life and death walk hand in hand, and where their closely guarded secrets will force them to make a terrible choice.

‘Incredibly ambitious, extremely powerful and moving’ – BBC Radio 4

Fatima Bhutto was born in Kabul. She is the author of a book of poetry, two works of non-fiction, including her bestselling memoir Songs of Blood and Sword, and the highly acclaimed novel The Shadow Of The Crescent Moon, which was longlisted in 2014 for the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Fatima Bhutto

The Runaways

Penguin Books Ltd

Imprint: Viking

Fiction

English

Published: 07/03/2019

ISBN: 9780241346990

Hardcover

Length: 432 Pages

RRP: £14.99

# new novel

Fatima Bhutto

The Runaways

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Fatima Bhutto

Gilles Speksneijder, een weinig uitgesproken man, bekleedt een bescheiden functie in een dienstverlenende organisatie.

Als hij van de ene op de andere dag wordt gepromoveerd tot assistentverhuiscoördinator, bezwijkt hij bijna onder zijn verantwoordelijkheden en taken. De tijdsdruk neemt toe en het verhuisproces raakt vertroebeld door machtsspelletjes, vileine roddels en complotten.

Als hij van de ene op de andere dag wordt gepromoveerd tot assistentverhuiscoördinator, bezwijkt hij bijna onder zijn verantwoordelijkheden en taken. De tijdsdruk neemt toe en het verhuisproces raakt vertroebeld door machtsspelletjes, vileine roddels en complotten.

Wanneer Gilles uit schimmige motieven een jonge vrouw meebrengt, een antikraakwacht die het verhuisproces dreigt te vertragen, verschuiven de verhoudingen in huize Speksneijder: terwijl Gilles naar de marge wordt gedrongen, neemt zijn vrouw steeds meer het heft in handen.

M.M. Schoenmakers werd geboren in Den Bosch (1949), studeerde af aan de Universiteit van Tilburg en vertrok in 1977 naar Suriname, waar hij werkte met indiaanse gemeenschappen in het binnenland. In 1989 keerde hij terug naar Nederland. Zijn Surinaamse jaren leidden tot vijf romans, die in de periode 1989-1998 bij De Bezige Bij verschenen. Na een lange stilte verscheen in 2015 opnieuw werk van zijn hand, de alom geprezen roman De wolkenridder. In februari 2019 verscheen de ontroerende en geestige roman De vlucht van Gilles Speksneijder.

Auteur: M.M. Schoenmakers

Titel: De vlucht van Gilles Speksneijder

Literaire roman

Taal: Nederlands

Paperback

256 pagina’s

Uitgever De Bezige Bij

2017

EAN 9789023454076

€ 21,99

# new novel

schoenmakers mm

de vlucht van Gilles Speksneijder

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive S-T, M.M. Schoenmakers

`Knikkeren?’ vraagt Tijger.

`Knikkeren?’ vraagt Tijger.

`Heb je penningen?’

`Twee. Ik zet. Jij gooit.’

Tijger gaat op zijn kont zitten, de benen uit elkaar, de penning, met de beeltenis van de Duitse keizer, staat op zijn rand. Mels probeert hem te raken, maar alle knikkers gaan er langs. Ze rollen Tijgers broekspijpen in.

De schoolbel maakt een einde aan het spel. Fluisterend lopen ze door de gang naar het natuurkundelokaal. Binnen ruikt het naar krijt en naar de meisjes die in het uur daarvoor les hebben gehad. Meisjes krijgen altijd apart natuurkundeles, omdat ze iets moeten leren wat jongens niet mogen weten.

Juf Elsbeth zet de fles kikkervisjes op haar lessenaar en begint te praten over het wonder van de schepping. Haar stem zakt weg in het geluid van motoren buiten. De ruiten van de klas trillen van het zware gebrom van de vrachtwagens die door de slurf van de silo worden leeggezogen. Een man staat op het dak van de silo en draait met een handel de slurf hoger op. Hij schreeuwt tegen de stem van de juffrouw in. `Joehoe, joehoe!’ Niemand lijkt hem te horen. Een van de ruiten van het klaslokaal protesteert tegen het lawaai op deze zonnige middag, waarop het rustig hoort te zijn, en springt met een knal in tweeën. Splinters spatten over de leerlingen, als kleine stukjes ijs.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (105)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Guy Commerman, een hoog gewaardeerde auteur bij Uitgeverij Kleinood & Grootzeer is op 10 januari 2019 overleden.

Juist op dat moment was zijn nieuwe bundel: Verhalen van de zandloper, voltooid. De bundel bevat zijn laatste gedichten en is tevens een eerbetoon aan deze veelzijdige dichter en aimabel mens.

Guy Commerman (1938 – 2019)

Verhalen van de zandloper

De derde bundel van Guy Commerman bij Kleinood & Grootzeer

Eerste druk 100 genummerde en door de auteur gesigneerde exemplaren. Boekje, 62 pagina’s,

gelijmd 21 x 10,5 cm.

ISBN/EAN 978-90-76644-93-6

€18,-

# Meer informatie bij Uitgeverij Kleinood & Grootzeer

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, In Memoriam, LITERARY MAGAZINES

Een wolk schuift voor de zon. De beelden van grootvader en het molenhuis lossen op. Mels hoort alleen nog de stemmen van het kerkhof. Als bijen zoemen ze rond zijn hoofd.

Er zijn ook stemmen die hij niet wil horen, maar het is moeilijk er zijn oren voor te sluiten. Hij hoort zijn vittende vader, die op hem kankert omdat hij lui en te speels is. `Je moet beter je best doen! Je verlummelt je tijd! Je bent net zo lui als je moeder, die zit ook altijd in de zon! Je denkt toch niet dat ik voor niets voor je werk! Zat je alweer in je bootje op de Wijer! Was je weer bij je grootvader Bernhard! Van die man leer je niets goeds!’

Er zijn ook stemmen die hij niet wil horen, maar het is moeilijk er zijn oren voor te sluiten. Hij hoort zijn vittende vader, die op hem kankert omdat hij lui en te speels is. `Je moet beter je best doen! Je verlummelt je tijd! Je bent net zo lui als je moeder, die zit ook altijd in de zon! Je denkt toch niet dat ik voor niets voor je werk! Zat je alweer in je bootje op de Wijer! Was je weer bij je grootvader Bernhard! Van die man leer je niets goeds!’

Hij rilt van afschuw. De kreten van zijn vader, die altijd terug blijven komen. Door zijn ongenoegen over het leven was hij zelf vroeg gestorven. Hij haatte de zon. Hij kende alleen plicht.

Om de stem van zijn vader terug te dringen in het graf, draait hij zijn hoofd weg en luistert naar de vogels die rond de silo vliegen. Hij wil nu niet denken. Het brengt de ergernis terug in zijn hoofd. Het wordt steeds moeilijker om die te onderdrukken. Zijn hersens raken erdoor op drift. Hij kan zich steeds minder goed beheersen. Zijn hoofd laat zich niet meer dwingen. Zijn hersens zijn aangetast. Hij herinnert zich dingen die hij niet meer kan plaatsen. Gesprekken die hij met Wilkington heeft gevoerd. Wilkington die hem vertelde hoe het bij hem thuis was. En over een kamertje dat bestemd was voor zijn zoon, maar dat altijd leeg was gebleven. Hij moet die gesprekken hebben gefantaseerd, want hij heeft Wilkington nooit gezien.

Nooit heeft hij geweten dat de graansilo zo veel vogels herbergde. Ze wonen in alle kieren en gaten. Ze vliegen door de kapotte ramen naar binnen en ze zingen en fluiten. Ze zijn vrolijk, maar misschien zouden ze zich ongerust moeten maken, nu Bouwbedrijf Leon van Wijk en Zonen een begin heeft gemaakt met de bouw van appartementen in de silo. De nesten zullen worden vernield.

Langgeleden is hij op het dak geweest, samen met Tijger en Thija. Twaalf jaar waren ze toen. Langs de stalen trap in de fabriek waren ze naar boven geklommen. Van boven had het dorp op een sprookjesdorp geleken.

Op hun rug hadden ze op het dak gelegen, met het gevoel veel dichter bij de wolken te zijn en er zo op te kunnen stappen om weg te zeilen. Onder een veel grotere hemel. En Thija had een gedicht van Jacob over zijn eenzaamheid voorgelezen.

De bouwlift komt omhoog en stopt. Hij hoort de stappen op het dak, achter zijn rug. Ze komen hem halen.

`Je zit hier mooi.’ Het is de stem van Tijger, achter hem, diep, zoals de stem van een zestigjarige. Hij schrikt niet eens dat Tijger zo dicht bij hem is.

Zijn vriend Tijger. In zijn dromen heeft hij altijd met Tijger gepraat. Soms was Tijger twaalf, maar vaak was hij net zo oud als hijzelf. In leeftijd blijkt hij gewoon meegegroeid, zoals een echte vriend voor het leven meegroeit.

`Kijk, het dak van mijn ouderlijk huis’, zegt Mels. `Ik ben er altijd gebleven. Ik heb er met mijn moeder gewoond tot ze stierf. Ik ben er gebleven toen ik trouwde. Als je erop neerkijkt, lijkt het heel mooi.’

`Op afstand is alles mooi’, zegt Tijger. `Maar het is écht een mooi dorp. Schilderachtig zelfs, omdat je nu de silo niet ziet. Als je beneden bent, zie je altijd die rottige toren.’

`Ze knappen de silo op’, zegt Mels. `Ze vinden hem mooi omdat hij oud is. Snap jij dat?’

`Oud is altijd mooi’, zegt Tijger. `Een natte oude krant die opdroogt in de zon wordt ook weer mooi. Ik blader graag in oude kranten. Op het kerkhof krijgen we geen andere kranten dan verwaaide oude kranten. Vaak zijn de letters bijna opgelost door zon en water. Je weet nooit precies wat je leest.’

`Zo is het met nieuw nieuws ook’, zegt Mels. `Je weet nooit precies wat ze je vertellen willen. Hoor jij de stemmen van beneden ook?’

`Waar praten ze over?’

`Veel zul je er niet meer van begrijpen. Alles is anders. Iedereen is anders. Bijna niemand van de mensen die hier nu wonen kent je nog.’

`En mijn zus?’

`Ze herinnert zich niet veel van je.’

`En mijn moeder?’

`Ze heeft zich opgehangen. Ze is nooit over het verlies van jou heen gekomen.’

`Wat spijt me dat’, zegt Tijger met een brok in zijn keel. `Als ik alles had geweten, zou ik niet zo’n waaghals zijn geweest.’

Hij loopt naar de rand van het dak en gaat zitten, zijn benen bungelend over de rand.

`Je bent nog net zo’n waaghals’, zegt Mels. Het valt hem op hoe kaal zijn vriend is geworden. Hij heeft veel weg van grootvader Bernhard.

`Ik wilde altijd alles voor honderd procent’, zegt Tijger.

`Als je toen niet verongelukt was, zou het later wel gebeurd zijn. Niet veel later. Als je zestien of twintig was geweest. Met jouw waaghalzerij zou je nooit oud zijn geworden.’

`Ik ben nooit bang geweest. Soms, in mijn slaap. Maar nu ben ik wel bang.’

`Waarvoor?’

`Voor het leven dat ik heb gemist.’

`Maar je bent teruggekomen.’

`Je weet het toch nog wel’, zegt Tijger. `John Wilkington. Je was er toch zeker van dat zijn ziel in jou doorleefde.’

`Dat denk ik nu nog.’

`De dochters van Wilkington hadden je zussen kunnen zijn.’

Mels is verbijsterd. Opeens begrijpt hij waarom zijn vader zo afstandelijk was. Dat hij nauwelijks woorden had voor zijn moeder. Dat hij altijd weg was.

`Je schrikt er toch niet van’, zegt Tijger. `Je bent uit liefde geboren, wat wil je meer? Zonder Wilkington op zolder was je er nooit geweest.’

`Je hebt gelijk. Ik moet hem dankbaar zijn.’

`Bovendien leef je voort. Je hebt een dochter. Kleinkinderen. Maar ik? Jij bent de enige die nog aan mij denkt. Straks, als jij ook weg bent, ben ik totaal vergeten. Dat maakt me bang. Ik ben bang voor de eenzaamheid. Om hier altijd te moeten blijven.’

`Misschien is het dat wat ze eeuwigheid noemen’, zegt Mels. `Dat je ergens voor altijd blijft.’

`Maar toch niet hier! Weet je nog dat wij vroeger ook wel eens stiekem op het dak van de silo stonden?’ Tijger schuift wat achteruit, trekt zijn benen op en gaat staan.

`Het is maar één keer gebeurd’, zegt Mels. `Toen Thija dat gedicht van Jacob las.’

`Vaker.’

`Dat herinner ik me niet.’

`Ik wilde vleugels maken, om naar beneden te zeilen.’

`Dat klopt. Jij wilde vliegen. Je hebt het niet geprobeerd. Je zou te pletter zijn gevallen.’

`Als iedereen zo denkt, durft niemand wat. Als niemand had willen vliegen, zouden er nog steeds geen vliegtuigen zijn.’

`Zou jij het vliegtuig hebben uitgevonden?’

`Dat denk ik wel. Als ik was blijven leven wel. Ik zou zeker hebben gevlogen.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (104)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Occupying the Stage: the Theater of May ’68 tells the story of student and worker uprisings in France through the lens of theater history, and the story of French theater through the lens of May ’68.

Based on detailed archival research and original translations, close readings of plays and historical documents, and a rigorous assessment of avant-garde theater history and theory, Occupying the Stage proposes that the French theater of 1959–71 forms a standalone paradigm called “The Theater of May ’68.”

Based on detailed archival research and original translations, close readings of plays and historical documents, and a rigorous assessment of avant-garde theater history and theory, Occupying the Stage proposes that the French theater of 1959–71 forms a standalone paradigm called “The Theater of May ’68.”

The book shows how French theater artists during this period used a strategy of occupation-occupying buildings, streets, language, words, traditions, and artistic processes-as their central tactic of protest and transformation. It further proposes that the Theater of May ’68 has left imprints on contemporary artists and activists, and that this theater offers a scaffolding on which to build a meaningful analysis of contemporary protest and performance in France, North America, and beyond.

At the book’s heart is an inquiry into how artists of the period used theater as a way to engage in political work and, concurrently, questioned and overhauled traditional theater practices so their art would better reflect the way they wanted the world to be. Occupying the Stage embraces the utopic vision of May ’68 while probing the period’s many contradictions. It thus affirms the vital role theater can play in the ongoing work of social change.

Occupying the Stage

The Theater of May ’68

Kate Bredeson (Author)

Publication Date: November 2018

Pages 232

Trim Size 6 x 9

Paper Text – $34.95

Northwestern University Press

Drama & Performance Studies

ISBN 978-0-8101-3815-5

# new books

Occupying the Stage

The Theater of May ’68

Kate Bredeson

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Protests of MAY 1968, THEATRE

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature