Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

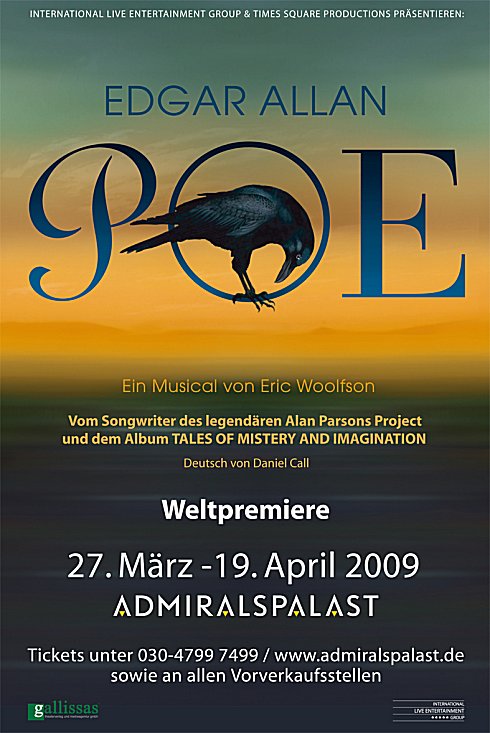

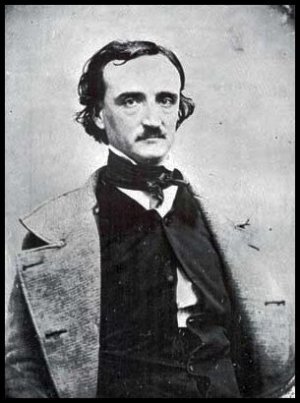

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809-1849)

Von Kempelen and his Discovery

After the very minute and elaborate paper by Arago, to say nothing of the summary in ‘Silliman’s Journal,’ with the detailed statement just published by Lieutenant Maury, it will not be supposed, of course, that in offering a few hurried remarks in reference to Von Kempelen’s discovery, I have any design to look at the subject in a scientific point of view. My object is simply, in the first place, to say a few words of Von Kempelen himself (with whom, some years ago, I had the honor of a slight personal acquaintance), since every thing which concerns him must necessarily, at this moment, be of interest; and, in the second place, to look in a general way, and speculatively, at the results of the discovery.

It may be as well, however, to premise the cursory observations which I have to offer, by denying, very decidedly, what seems to be a general impression (gleaned, as usual in a case of this kind, from the newspapers), viz.: that this discovery, astounding as it unquestionably is, is unanticipated.

By reference to the ‘Diary of Sir Humphrey Davy’ (Cottle and Munroe, London, pp. 150), it will be seen at pp. 53 and 82, that this illustrious chemist had not only conceived the idea now in question, but had actually made no inconsiderable progress, experimentally, in the very identical analysis now so triumphantly brought to an issue by Von Kempelen, who although he makes not the slightest allusion to it, is, without doubt (I say it unhesitatingly, and can prove it, if required), indebted to the ‘Diary’ for at least the first hint of his own undertaking.

The paragraph from the ‘Courier and Enquirer,’ which is now going the rounds of the press, and which purports to claim the invention for a Mr. Kissam, of Brunswick, Maine, appears to me, I confess, a little apocryphal, for several reasons; although there is nothing either impossible or very improbable in the statement made. I need not go into details. My opinion of the paragraph is founded principally upon its manner. It does not look true. Persons who are narrating facts, are seldom so particular as Mr. Kissam seems to be, about day and date and precise location. Besides, if Mr. Kissam actually did come upon the discovery he says he did, at the period designated — nearly eight years ago — how happens it that he took no steps, on the instant, to reap the immense benefits which the merest bumpkin must have known would have resulted to him individually, if not to the world at large, from the discovery? It seems to me quite incredible that any man of common understanding could have discovered what Mr. Kissam says he did, and yet have subsequently acted so like a baby — so like an owl — as Mr. Kissam admits that he did. By-the-way, who is Mr. Kissam? and is not the whole paragraph in the ‘Courier and Enquirer’ a fabrication got up to ‘make a talk’? It must be confessed that it has an amazingly moon-hoaxy-air. Very little dependence is to be placed upon it, in my humble opinion; and if I were not well aware, from experience, how very easily men of science are mystified, on points out of their usual range of inquiry, I should be profoundly astonished at finding so eminent a chemist as Professor Draper, discussing Mr. Kissam’s (or is it Mr. Quizzem’s?) pretensions to the discovery, in so serious a tone.

But to return to the ‘Diary’ of Sir Humphrey Davy. This pamphlet was not designed for the public eye, even upon the decease of the writer, as any person at all conversant with authorship may satisfy himself at once by the slightest inspection of the style. At page 13, for example, near the middle, we read, in reference to his researches about the protoxide of azote: ‘In less than half a minute the respiration being continued, diminished gradually and were succeeded by analogous to gentle pressure on all the muscles.’ That the respiration was not ‘diminished,’ is not only clear by the subsequent context, but by the use of the plural, ‘were.’ The sentence, no doubt, was thus intended: ‘In less than half a minute, the respiration [being continued, these feelings] diminished gradually, and were succeeded by [a sensation] analogous to gentle pressure on all the muscles.’ A hundred similar instances go to show that the MS. so inconsiderately published, was merely a rough note-book, meant only for the writer’s own eye, but an inspection of the pamphlet will convince almost any thinking person of the truth of my suggestion. The fact is, Sir Humphrey Davy was about the last man in the world to commit himself on scientific topics. Not only had he a more than ordinary dislike to quackery, but he was morbidly afraid of appearing empirical; so that, however fully he might have been convinced that he was on the right track in the matter now in question, he would never have spoken out, until he had every thing ready for the most practical demonstration. I verily believe that his last moments would have been rendered wretched, could he have suspected that his wishes in regard to burning this ‘Diary’ (full of crude speculations) would have been unattended to; as, it seems, they were. I say ‘his wishes,’ for that he meant to include this note-book among the miscellaneous papers directed ‘to be burnt,’ I think there can be no manner of doubt. Whether it escaped the flames by good fortune or by bad, yet remains to be seen. That the passages quoted above, with the other similar ones referred to, gave Von Kempelen the hint, I do not in the slightest degree question; but I repeat, it yet remains to be seen whether this momentous discovery itself (momentous under any circumstances) will be of service or disservice to mankind at large. That Von Kempelen and his immediate friends will reap a rich harvest, it would be folly to doubt for a moment. They will scarcely be so weak as not to ‘realize,’ in time, by large purchases of houses and land, with other property of intrinsic value.

In the brief account of Von Kempelen which appeared in the ‘Home Journal,’ and has since been extensively copied, several misapprehensions of the German original seem to have been made by the translator, who professes to have taken the passage from a late number of the Presburg ‘Schnellpost.’ ‘Viele’ has evidently been misconceived (as it often is), and what the translator renders by ‘sorrows,’ is probably ‘lieden,’ which, in its true version, ‘sufferings,’ would give a totally different complexion to the whole account; but, of course, much of this is merely guess, on my part.

Von Kempelen, however, is by no means ‘a misanthrope,’ in appearance, at least, whatever he may be in fact. My acquaintance with him was casual altogether; and I am scarcely warranted in saying that I know him at all; but to have seen and conversed with a man of so prodigious a notoriety as he has attained, or will attain in a few days, is not a small matter, as times go.

‘The Literary World’ speaks of him, confidently, as a native of Presburg (misled, perhaps, by the account in ‘The Home Journal’) but I am pleased in being able to state positively, since I have it from his own lips, that he was born in Utica, in the State of New York, although both his parents, I believe, are of Presburg descent. The family is connected, in some way, with Maelzel, of Automaton-chess-player memory. In person, he is short and stout, with large, fat, blue eyes, sandy hair and whiskers, a wide but pleasing mouth, fine teeth, and I think a Roman nose. There is some defect in one of his feet. His address is frank, and his whole manner noticeable for bonhomie. Altogether, he looks, speaks, and acts as little like ‘a misanthrope’ as any man I ever saw. We were fellow-sojouners for a week about six years ago, at Earl’s Hotel, in Providence, Rhode Island; and I presume that I conversed with him, at various times, for some three or four hours altogether. His principal topics were those of the day, and nothing that fell from him led me to suspect his scientific attainments. He left the hotel before me, intending to go to New York, and thence to Bremen; it was in the latter city that his great discovery was first made public; or, rather, it was there that he was first suspected of having made it. This is about all that I personally know of the now immortal Von Kempelen; but I have thought that even these few details would have interest for the public.

There can be little question that most of the marvellous rumors afloat about this affair are pure inventions, entitled to about as much credit as the story of Aladdin’s lamp; and yet, in a case of this kind, as in the case of the discoveries in California, it is clear that the truth may be stranger than fiction. The following anecdote, at least, is so well authenticated, that we may receive it implicitly.

Von Kempelen had never been even tolerably well off during his residence at Bremen; and often, it was well known, he had been put to extreme shifts in order to raise trifling sums. When the great excitement occurred about the forgery on the house of Gutsmuth & Co., suspicion was directed toward Von Kempelen, on account of his having purchased a considerable property in Gasperitch Lane, and his refusing, when questioned, to explain how he became possessed of the purchase money. He was at length arrested, but nothing decisive appearing against him, was in the end set at liberty. The police, however, kept a strict watch upon his movements, and thus discovered that he left home frequently, taking always the same road, and invariably giving his watchers the slip in the neighborhood of that labyrinth of narrow and crooked passages known by the flash name of the ‘Dondergat.’ Finally, by dint of great perseverance, they traced him to a garret in an old house of seven stories, in an alley called Flatzplatz, — and, coming upon him suddenly, found him, as they imagined, in the midst of his counterfeiting operations. His agitation is represented as so excessive that the officers had not the slightest doubt of his guilt. After hand-cuffing him, they searched his room, or rather rooms, for it appears he occupied all the mansarde.

Opening into the garret where they caught him, was a closet, ten feet by eight, fitted up with some chemical apparatus, of which the object has not yet been ascertained. In one corner of the closet was a very small furnace, with a glowing fire in it, and on the fire a kind of duplicate crucible — two crucibles connected by a tube. One of these crucibles was nearly full of lead in a state of fusion, but not reaching up to the aperture of the tube, which was close to the brim. The other crucible had some liquid in it, which, as the officers entered, seemed to be furiously dissipating in vapor. They relate that, on finding himself taken, Kempelen seized the crucibles with both hands (which were encased in gloves that afterwards turned out to be asbestic), and threw the contents on the tiled floor. It was now that they hand-cuffed him; and before proceeding to ransack the premises they searched his person, but nothing unusual was found about him, excepting a paper parcel, in his coat-pocket, containing what was afterward ascertained to be a mixture of antimony and some unknown substance, in nearly, but not quite, equal proportions. All attempts at analyzing the unknown substance have, so far, failed, but that it will ultimately be analyzed, is not to be doubted.

Passing out of the closet with their prisoner, the officers went through a sort of ante-chamber, in which nothing material was found, to the chemist’s sleeping-room. They here rummaged some drawers and boxes, but discovered only a few papers, of no importance, and some good coin, silver and gold. At length, looking under the bed, they saw a large, common hair trunk, without hinges, hasp, or lock, and with the top lying carelessly across the bottom portion. Upon attempting to draw this trunk out from under the bed, they found that, with their united strength (there were three of them, all powerful men), they ‘could not stir it one inch.’ Much astonished at this, one of them crawled under the bed, and looking into the trunk, said:

‘No wonder we couldn’t move it — why it’s full to the brim of old bits of brass!’ Putting his feet, now, against the wall so as to get a good purchase, and pushing with all his force, while his companions pulled with an theirs, the trunk, with much difficulty, was slid out from under the bed, and its contents examined. The supposed brass with which it was filled was all in small, smooth pieces, varying from the size of a pea to that of a dollar; but the pieces were irregular in shape, although more or less flat-looking, upon the whole, ‘very much as lead looks when thrown upon the ground in a molten state, and there suffered to grow cool.’ Now, not one of these officers for a moment suspected this metal to be any thing but brass. The idea of its being gold never entered their brains, of course; how could such a wild fancy have entered it? And their astonishment may be well conceived, when the next day it became known, all over Bremen, that the ‘lot of brass’ which they had carted so contemptuously to the police office, without putting themselves to the trouble of pocketing the smallest scrap, was not only gold — real gold — but gold far finer than any employed in coinage-gold, in fact, absolutely pure, virgin, without the slightest appreciable alloy.

I need not go over the details of Von Kempelen’s confession (as far as it went) and release, for these are familiar to the public. That he has actually realized, in spirit and in effect, if not to the letter, the old chimaera of the philosopher’s stone, no sane person is at liberty to doubt. The opinions of Arago are, of course, entitled to the greatest consideration; but he is by no means infallible; and what he says of bismuth, in his report to the Academy, must be taken cum grano salis. The simple truth is, that up to this period all analysis has failed; and until Von Kempelen chooses to let us have the key to his own published enigma, it is more than probable that the matter will remain, for years, in statu quo. All that as yet can fairly be said to be known is, that ‘Pure gold can be made at will, and very readily from lead in connection with certain other substances, in kind and in proportions, unknown.’

Speculation, of course, is busy as to the immediate and ultimate results of this discovery — a discovery which few thinking persons will hesitate in referring to an increased interest in the matter of gold generally, by the late developments in California; and this reflection brings us inevitably to another — the exceeding inopportuneness of Von Kempelen’s analysis. If many were prevented from adventuring to California, by the mere apprehension that gold would so materially diminish in value, on account of its plentifulness in the mines there, as to render the speculation of going so far in search of it a doubtful one — what impression will be wrought now, upon the minds of those about to emigrate, and especially upon the minds of those actually in the mineral region, by the announcement of this astounding discovery of Von Kempelen? a discovery which declares, in so many words, that beyond its intrinsic worth for manufacturing purposes (whatever that worth may be), gold now is, or at least soon will be (for it cannot be supposed that Von Kempelen can long retain his secret), of no greater value than lead, and of far inferior value to silver. It is, indeed, exceedingly difficult to speculate prospectively upon the consequences of the discovery, but one thing may be positively maintained — that the announcement of the discovery six months ago would have had material influence in regard to the settlement of California.

In Europe, as yet, the most noticeable results have been a rise of two hundred per cent. in the price of lead, and nearly twenty-five per cent. that of silver.

Edgar Allan Poe: Von Kempelen and his Discovery

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Chess in literature, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

.jpg)

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809-1849)

The Masque of the Red Death

The red death had long devastated the country. No pestilence had ever been so fatal, or so hideous. Blood was its Avatar and its seal–the madness and the horror of blood. There were sharp pains, and sudden dizziness, and then profuse bleeding at the pores, with dissolution. The scarlet stains upon the body and especially upon the face of the victim, were the pest ban which shut him out from the aid and from the sympathy of his fellow-men. And the whole seizure, progress, and termination of the disease, were incidents of half an hour.

But Prince Prospero was happy and dauntless and sagacious. When his dominions were half depopulated, he summoned to his presence a thousand hale and light-hearted friends from among the knights and dames of his court, and with these retired to the deep seclusion of one of his crenellated abbeys. This was an extensive and magnificent structure, the creation of the prince’s own eccentric yet august taste. A strong and lofty wall girdled it in. This wall had gates of iron. The courtiers, having entered, brought furnaces and massy hammers and welded the bolts.

They resolved to leave means neither of ingress nor egress to the sudden impulses of despair or of frenzy from within. The abbey was amply provisioned. With such precautions the courtiers might bid defiance to contagion. The external world could take care of itself. In the meantime it was folly to grieve or to think. The prince had provided all the appliances of pleasure. There were buffoons, there were improvisatori, there were ballet-dancers, there were musicians, there was Beauty, there was wine. All these and security were within. Without was the “Red Death.”

It was toward the close of the fifth or sixth month of his seclusion that the Prince Prospero entertained his thousand friends at a masked ball of the most unusual magnificence.

It was a voluptuous scene, that masquerade. But first let me tell of the rooms in which it was held. There were seven–an imperial suite, In many palaces, however, such suites form a long and straight vista, while the folding doors slide back nearly to the walls on either hand, so that the view of the whole extant is scarcely impeded. Here the case was very different; as might have been expected from the duke’s love of the “bizarre.” The apartments were so irregularly disposed that the vision embraced but little more than one at a time. There was a sharp turn at the right and left, in the middle of each wall, a tall and narrow Gothic window looked out upon a closed corridor of which pursued the windings of the suite. These windows were of stained glass whose color varied in accordance with the prevailing hue of the decorations of the chamber into which it opened. That at the eastern extremity was hung, for example, in blue–and vividly blue were its windows. The second chamber was purple in its ornaments and tapestries, and here the panes were purple. The third was green throughout, and so were the casements. The fourth was furnished and lighted with orange–the fifth with white–the sixth with violet. The seventh apartment was closely shrouded in black velvet tapestries that hung all over the ceiling and down the walls, falling in heavy folds upon a carpet of the same material and hue. But in this chamber only, the color of the windows failed to correspond with the decorations. The panes were scarlet–a deep blood color. Now in no one of any of the seven apartments was there any lamp or candelabrum, amid the profusion of golden ornaments that lay scattered to and fro and depended from the roof. There was no light of any kind emanating from lamp or candle within the suite of chambers. But in the corridors that followed the suite, there stood, opposite each window, a heavy tripod, bearing a brazier of fire, that projected its rays through the tinted glass and so glaringly lit the room. And thus were produced a multitude of gaudy and fantastic appearances. But in the western or back chamber the effect of the fire-light that streamed upon the dark hangings through the blood-tinted panes was ghastly in the extreme, and produced so wild a look upon the countenances of those who entered, that there were few of the company bold enough to set foot within its precincts at all. It was within this apartment, also, that there stood against the western wall, a gigantic clock of ebony. It pendulum swung to and fro with a dull, heavy, monotonous clang; and when the minute-hand made the circuit of the face, and the hour was to be stricken, there came from the brazen lungs of the clock a sound which was clear and loud and deep and exceedingly musical, but of so peculiar a note and emphasis that, at each lapse of an hour, the musicians of the orchestra were constrained to pause, momentarily, in their performance, to hearken to the sound; and thus the waltzers perforce ceased their evolutions; and there was a brief disconcert of the whole gay company; and while the chimes of the clock yet rang. it was observed that the giddiest grew pale, and the more aged and sedate passed their hands over their brows as if in confused revery or meditation. But when the echoes had fully ceased, a light laughter at once pervaded the assembly; the musicians looked at each other and smiled as if at their own nervousness and folly, and made whispering vows, each to the other, that the next chiming of the clock should produce in them no similar emotion; and then, after the lapse of sixty minutes (which embrace three thousand and six hundred seconds of Time that flies), there came yet another chiming of the clock, and then were the same disconcert and tremulousness and meditation as before. But, in spite of these things, it was a gay and magnificent revel. The tastes of the duke were peculiar. He had a fine eye for color and effects. He disregarded the “decora” of mere fashion. His plans were bold and fiery, and his conceptions glowed with barbaric lustre. There are some who would have thought him mad. His followers felt that he was not. It was necessary to hear and see and touch him to be sure he was not.

He had directed, in great part, the movable embellishments of the seven chambers, upon occasion of this great fete; and it was his own guiding taste which had given character to the masqueraders. Be sure they were grotesque. There were much glare and glitter and piquancy and phantasm–much of what has been seen in “Hernani.” There were arabesque figures with unsuited limbs and appointments. There were delirious fancies such as the madman fashions. There were much of the beautiful, much of the wanton, much of the bizarre, something of the terrible, and not a little of that which might have excited disgust. To and fro in the seven chambers stalked, in fact, a multitude of dreams. And these the dreams–writhed in and about, taking hue from the rooms, and causing the wild music of the orchestra to seem as the echo of their steps. And, anon, there strikes the ebony clock which stands in the hall of the velvet. And then, for a moment, all is still, and all is silent save the voice of the clock. The dreams are stiff-frozen as they stand. But the echoes of the chime die away–they have endured but an instant–and a light half-subdued laughter floats after them as they depart. And now the music swells, and the dreams live, and writhe to and fro more merrily than ever, taking hue from the many-tinted windows through which stream the rays of the tripods. But to the chamber which lies most westwardly of the seven there are now none of the maskers who venture, for the night is waning away; and there flows a ruddier light through the blood-colored panes; and the blackness of the sable drapery appalls; and to him whose foot falls on the sable carpet, there comes from the near clock of ebony a muffled peal more solemnly emphatic than any which reaches their ears who indulge in the more remote gaieties of the other apartments.

But these other apartments were densely crowded, and in them beat feverishly the heart of life. And the revel went whirlingly on, until at length there commenced the sounding of midnight upon the clock. And then the music ceased, as I have told; and the evolutions of the waltzers were quieted; and there was an uneasy cessation of all things as before. But now there were twelve strokes to be sounded by the bell of the clock; and thus it happened, perhaps that more of thought crept, with more of time into the meditations of the thoughtful among those who revelled. And thus too, it happened, that before the last echoes of the last chime had utterly sunk into silence, there were many individuals in the crowd who had found leisure to become aware of the presence of a masked figure which had arrested the attention of no single individual before. And the rumor of this new presence having spread itself whisperingly around, there arose at length from the whole company a buzz, or murmur, of horror, and of disgust.

In an assembly of phantasms such as I have painted, it may well be supposed that no ordinary appearance could have excited such sensation. In truth the masquerade license of the night was nearly unlimited; but the figure in question had out-Heroded Herod, and gone beyond the bounds of even the prince’s indefinite decorum. There are chords in the hearts of the most reckless which cannot be touched without emotion. Even with the utterly lost, to whom life and death are equally jests, there are matters of which no jest can be made. The whole company, indeed, seemed now deeply to feel that in the costume and bearing of the stranger neither wit nor propriety existed. The figure was tall and gaunt, and shrouded from head to foot in the habiliments of the grave. The mask which concealed the visage was made so nearly to resemble the countenance of a stiffened corpse that the closest scrutiny must have difficulty in detecting the cheat. And yet all this might have been endured, if not approved, by the mad revellers around. But the mummer had gone so far as to assume the type of the Red Death. His vesture was dabbled in blood–and his broad brow, with all the features of his face, was besprinkled with the scarlet horror.

When the eyes of Prince Prospero fell on this spectral image (which, with a slow and solemn movement, as if more fully to sustain its role, stalked to and fro among the waltzers) he was seen to be convulsed, in the first moment with a strong shudder either of terror or distaste; but in the next, his brow reddened with rage.

“Who dares”–he demanded hoarsely of the courtiers who stood near him–“who dares insult us with this blasphemous mockery? Seize him and unmask him–that we may know whom we have to hang, at sunrise, from the battlements!”

It was in the eastern or blue chamber in which stood Prince Prospero as he uttered these words. They rang throughout the seven rooms loudly and clearly, for the prince was a bold and robust man, and the music had become hushed at the waving of his hand.

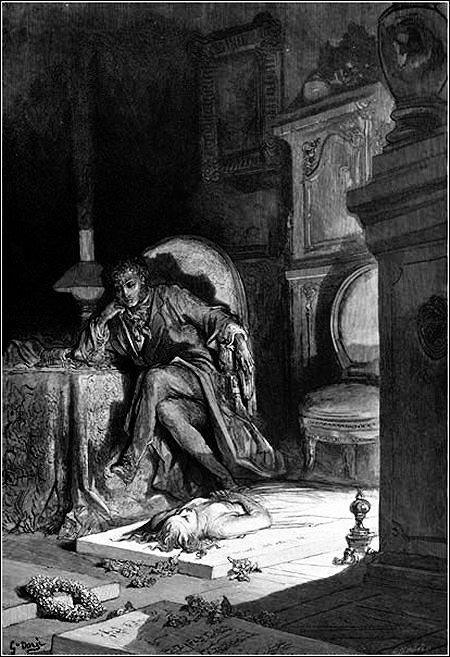

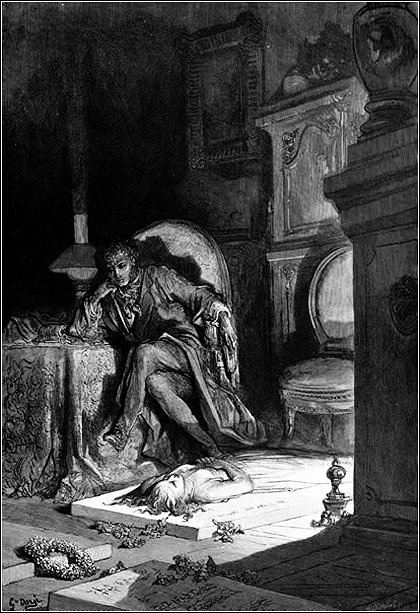

It was in the blue room where stood the prince, with a group of pale courtiers by his side. At first, as he spoke, there was a slight rushing movement of this group in the direction of the intruder, who, at the moment was also near at hand, and now, with deliberate and stately step, made closer approach to the speaker. But from a certain nameless awe with which the mad assumptions of the mummer had inspired the whole party, there were found none who put forth a hand to seize him; so that, unimpeded, he passed within a yard of the prince’s person; and while the vast assembly, as with one impulse, shrank from the centers of the rooms to the walls, he made his way uninterruptedly, but with the same solemn and measured step which had distinguished him from the first, through the blue chamber to the purple–to the purple to the green–through the green to the orange–through this again to the white–and even thence to the violet, ere a decided movement had been made to arrest him. It was then, however, that the Prince Prospero, maddened with rage and the shame of his own momentary cowardice, rushed hurriedly through the six chambers, while none followed him on account of a deadly terror that had seized upon all. He bore aloft a drawn dagger, and had approached, in rapid impetuosity, to within three or four feet of the retreating figure, when the latter, having attained the extremity of the velvet apartment, turned suddenly and confronted his pursuer. There was a sharp cry–and the dagger dropped gleaming upon the sable carpet, upon which most instantly afterward, fell prostrate in death the Prince Prospero. Then summoning the wild courage of despair, a throng of the revellers at once threw themselves into the black apartment, and seizing the mummer whose tall figure stood erect and motionless within the shadow of the ebony clock, gasped in unutterable horror at finding the grave cerements and corpse-like mask, which they handled with so violent a rudeness, untenanted by any tangible form.

And now was acknowledged the presence of the Red Death. He had come like a thief in the night. And one by one dropped the revellers in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel, and died each in the despairing posture of his fall. And the life of the ebony clock went out with that of the last of the gay. And the flames of the tripods expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.

Edgar Allan Poe: The Masque of the Red Death

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

.jpg)

E D G A R A L L A N P O E

(1809-1849)

Six Poems

The Assignation

Thou wast all that to me, love,

For which my soul did pine-

A green isle in the sea, love,

A fountain and a shrine,

All wreathed with fairy fruits and flowers,

And all the flowers were mine.

Ah, dream too bright to last!

Ah, starry Hope! that didst arise

But to be overcast!

A voice from out the Future cries,

"Onward!"- but o’er the Past

(Dim gulf!) my spirit hovering lies

Mute, motionless, aghast!

For, alas! alas! with me

The light of life is o’er!

"No more– no more– no more,"

(Such language holds the solemn sea

To the sands upon the shore)

Shall bloom the thunder-blasted tree

Or the stricken eagle soar!

And all my hours are trances,

And all my nightly dreams

Are where thy dark eye glances,

And where thy footstep gleams-

In what ethereal dances,

By what Italian streams.

Alas! for that accursed time

They bore thee o’er the billow,

From Love to titled age and crime,

And an unholy pillow!–

From me, and from our misty clime,

Where weeps the silver willow!

Alone

From childhood’s hour I have not been

As others were; I have not seen

As others saw; I could not bring

My passions from a common spring.

From the same source I have not taken

My sorrow; I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone;

And all I loved, I loved alone.

Then- in my childhood, in the dawn

Of a most stormy life- was drawn

From every depth of good and ill

The mystery which binds me still:

From the torrent, or the fountain,

From the red cliff of the mountain,

From the sun that round me rolled

In its autumn tint of gold,

From the lightning in the sky

As it passed me flying by,

From the thunder and the storm,

And the cloud that took the form

(When the rest of Heaven was blue)

Of a demon in my view.

The Haunted Palace

In the greenest of our valleys

By good angels tenanted,

Once a fair and stately palace —

Snow-white palace — reared its head.

In the monarch thought’s dominion —

It stood there!

Never Seraph spread his pinion

Over fabric half so fair.

Banners yellow, glorious, golden,

On its roof did float and flow —

This — all this — was in the olden

Time long ago —

And every gentle air that dallied,

In that sweet day,

Along the rampart plumed and pallid,

A winged odour went away.

All wanderers in that happy valley,

Through two luminous windows saw

Spirits moving musically

To a lute’s well tuned law,

Round about a throne where sitting

(Porphyrogene!)

In state his glory well befitting,

The sovereign of the realm was seen.

And all with pearl and ruby glowing

Was the fair palace door ;

Through which came flowing, flowing, flowing,

And sparkling evermore,

A troop of echoes, whose sweet duty

Was but to sing

In voices of surpassing beauty,

The wit and wisdom of their king.

But evil things in robes of sorrow,

Assailed the monarch’s high estate!

Ah, let us mourn — for never morrow

Shall dawn upon him desolate!

And round about his home the glory,

That blushed and bloomed,

Is but a dim-remembered story

Of the old time entombed.

And travellers now within that valley,

Through the red-litten windows, see

Vast forms that move fantastically

To a discordant melody;

While, like a rapid ghastly river,

Through the pale door;

A hideous throng rush out forever,

And laugh — but smile no more.

The Valley of Unrest

Once it smiled a silent dell

Where the people did not dwell;

They had gone unto the wars,

Trusting to the mild-eyed stars,

Nightly, from their azure towers,

To keep watch above the flowers,

In the midst of which all day

The red sunlight lazily lay.

Now each visitor shall confess

The sad valley’s restlessness.

Nothing there is motionless-

Nothing save the airs that brood

Over the magic solitude.

Ah, by no wind are stirred those trees

That palpitate like the chill seas

Around the misty Hebrides!

Ah, by no wind those clouds are driven

That rustle through the unquiet Heaven

Uneasily, from morn till even,

Over the violets there that lie

In myriad types of the human eye-

Over the lilies there that wave

And weep above a nameless grave!

They wave: — from out their fragrant tops

Eternal dews come down in drops.

They weep: — from off their delicate stems

Perennial tears descend in gems.

The Valley Nis

Far away — far away —

Far away — as far at least

Lies that valley as the day

Down within the golden east —

All things lovely — are not they

Far away — far away ?

It is called the valley Nis.

And a Syriac tale there is

Thereabout which Time hath said

Shall not be interpreted.

Something about Satan’s dart —

Something about angel wings —

Much about a broken heart —

All about unhappy things:

But "the valley Nis" at best

Means "the valley of unrest."

Once it smil’d a silent dell

Where the people did not dwell,

Having gone unto the wars —

And the sly, mysterious stars,

With a visage full of meaning,

O’er the unguarded flowers were leaning:

Or the sun ray dripp’d all red

Thro’ the tulips overhead,

Then grew paler as it fell

On the quiet Asphodel.

Now the unhappy shall confess

Nothing there is motionless:

Helen, like thy human eye

There th’ uneasy violets lie —

There the reedy grass doth wave

Over the old forgotten grave —

One by one from the tree top

There the eternal dews do drop —

There the vague and dreamy trees

Do roll like seas in northern breeze

Around the stormy Hebrides —

There the gorgeous clouds do fly,

Rustling everlastingly,

Through the terror-stricken sky,

Rolling like a waterfall

O’er th’ horizon’s fiery wall —

There the moon doth shine by night

With a most unsteady light —

There the sun doth reel by day

"Over the hills and far away."

.jpg)

Evening Star

‘Twas noontide of summer,

And mid-time of night;

And stars, in their orbits,

Shone pale, thro’ the light

Of the brighter, cold moon,

‘Mid planets her slaves,

Herself in the Heavens,

Her beam on the waves.

I gazed awhile

On her cold smile;

Too cold— too cold for me—

There pass’d, as a shroud,

A fleecy cloud,

And I turned away to thee,

Proud Evening Star,

In thy glory afar,

And dearer thy beam shall be;

For joy to my heart

Is the proud part

Thou bearest in Heaven at night,

And more I admire

Thy distant fire,

Than that colder, lowly light.

The End

Edgar Allan Poe: Six Poems

KEMP=MAG poetry magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

EDGAR ALLAN POE

(1809-1849)

Bicentennial of Poe’s birthday

on January 19, 1809

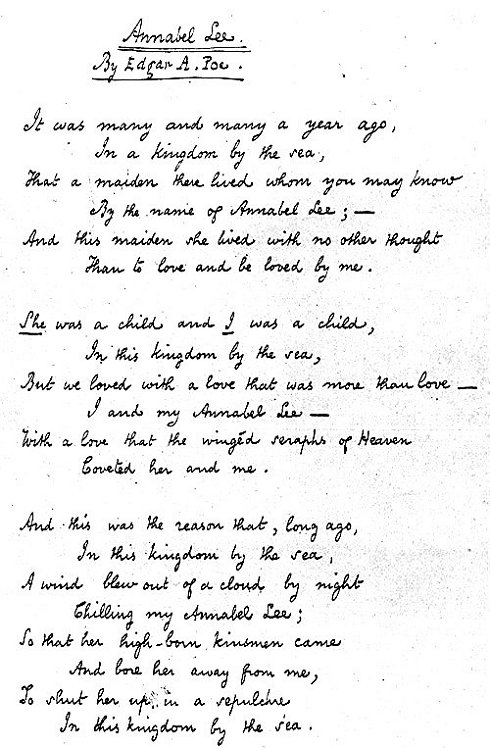

Annabel Lee

by E. A. Poe

It was many and many a year ago,

In a kingdom by the sea,

That a maiden there lived whom you may know

By the name of Annabel Lee;

And this maiden she lived with no other thought

Than to love and be loved by me.

I was a child and she was a child,

In this kingdom by the sea;

But we loved with a love that was more than love-

I and my Annabel Lee;

With a love that the winged seraphs of heaven

Coveted her and me.

And this was the reason that, long ago,

In this kingdom by the sea,

A wind blew out of a cloud, chilling

My beautiful Annabel Lee;

So that her highborn kinsman came

And bore her away from me,

To shut her up in a sepulchre

In this kingdom by the sea.

The angels, not half so happy in heaven,

Went envying her and me-

Yes!- that was the reason (as all men know,

In this kingdom by the sea)

That the wind came out of the cloud by night,

Chilling and killing my Annabel Lee.

But our love it was stronger by far than the love

Of those who were older than we-

Of many far wiser than we-

And neither the angels in heaven above,

Nor the demons down under the sea,

Can ever dissever my soul from the soul

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee.

For the moon never beams without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling- my darling- my life and my bride,

In the sepulchre there by the sea,

In her tomb by the sounding sea.

.jpg)

200th Birthday of Edgar Allan Poe 1809-2009

born in Boston U.S.A. – January 19, 1809

KEMP=MAG poetry magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

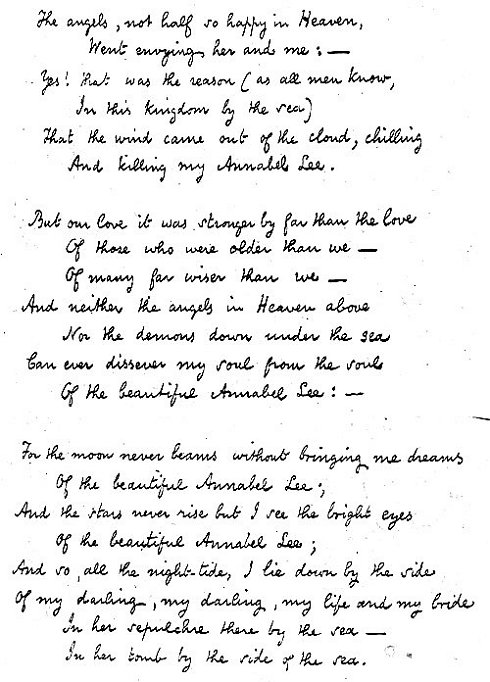

E D G A R A L L A N P O E

the new musical by Eric Woolfson

has its World Premier in Berlin on

March 27th, 2009

The year 2009 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of Edgar Allan Poe, one of the world’s most influential writers and author of “The Raven” and “The Fall of the House of Usher”. Poe is the inventor of the Detective Novel and the Father of Science Fiction. Sherlock Holmes was based on a character Poe wrote 60 years before Conan Doyle and he is universally acknowledged as the inspiration of writers such as H G Wells (War of the Worlds), Jules Verne (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea) and as George Bernard Shaw said, “We others simply take off our hats and let Mr Poe go first”.

.jpg)

Eric Woolfson is the creator and writer of the “The Alan Parsons Project” and writer of the musicals Freudiana, Gaudi, Gambler and Dancing Shadows. In writing this new musical, Woolfson has returned to his greatest inspiration, Edgar Allan Poe, 30 years after the great success of the first APP-Album “Tales of Mystery and Imagination” which was based on the stories of Edgar Allan Poe and has sold over 8 million copies worldwide.

“When I wrote and recorded Tales of Mystery and Imagination over 30 years ago. I was aware that there was more to the subject than I had explored at that stage. Many years later, I now feel that the time is right for me to revisit my hero, Edgar Allan Poe”, Eric Woolfson describes what motivated him to write his latest work.

.jpg)

In his latest musical, Woolfson presents an intoxicating view of the intriguing details of Poe’s remarkable life, which inspired his works: His mother dying in his arms when he was three years old, being forcefully separated from his first love, the tragic death of his young wife and his misplaced trust in Rufus Griswold, a rival poet motivated by jealousy and hatred. Even Poe’s death is shrouded in the mystery he became so famous for creating. These real events from Poe’s bizarre life intertwined with some of his greatest works, form the basis of the story of this new musical.

Based on the highly acclaimed showcase at the legendary Abbey Road Studios in November 2003, Eric Woolfson has developed an outstanding musical, which has taken his whole career to bring to fruition. A new album ‘Edgar Allan Poe’ containing all 17 songs from the musical will be released in January 2009. Woolfson also sings two song from the Edgar Allan Poe musical on his new album ‘Eric Woolfson sings The Alan Parsons Project That Never Was’ which will be released in January 2009 (www.the-alan-parsons-project-that-never-was.com).

EDGAR ALLAN POE – the Musical by Eric Woolfson will have it´s world premier on March 27th at the 1,700 seat Admiralspalast Theatre, Berlin.

The Musical will be directed by Frank Alva Buecheler, Setdesign & costumes by Christoph Weyers, Musical Director: Volker Plangg, Choreographer: Jaroslaw Staniek

.jpg)

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: Art & Literature News, Edgar Allan Poe, THEATRE

fleursdumal magazine

More in: Edgar Allan Poe, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

EDGAR ALLAN POE poetry

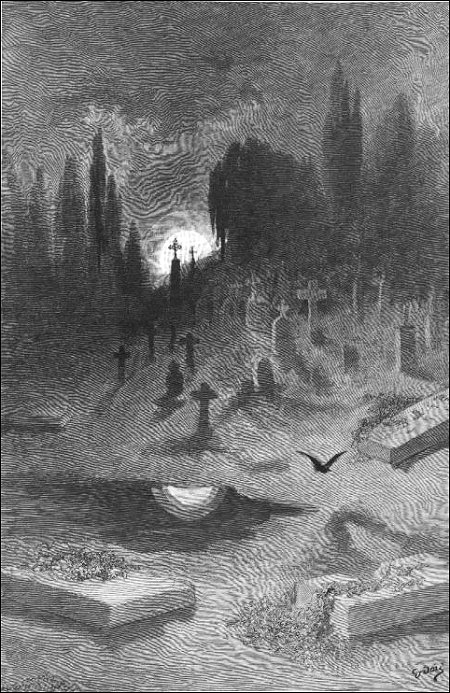

Spirits Of The Dead

1

Thy soul shall find itself alone

‘Mid dark thoughts of the grey tomb-stone-

Not one, of all the crowd, to pry

Into thine hour of secrecy:

2

Be silent in that solitude,

Which is not loneliness- for then

The spirits of the dead, who stood

In life before thee, are again

In death around thee, and their will

Shall overshadow thee; be still.

3

The night, tho’ clear- shall frown-

And the stars shall not look down,

From their high thrones in the heaven

With light like Hope to mortals given-

But their red orbs, without beam,

To thy weariness shall seem

As a burning and a fever

Which would cling to thee for ever.

4

Now are thoughts thou shalt not banish-

Now are visions ne’er to vanish-

From thy spirit shall they pass

No more- like dew-drop from the grass.

5

The breeze, the breath of God, is still,

And the mist upon the hill

Shadowy – shadowy – yet unbroken,

Is a symbol and a token-

How it hangs upon the trees,

A mystery of mysteries! –

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809-1849)

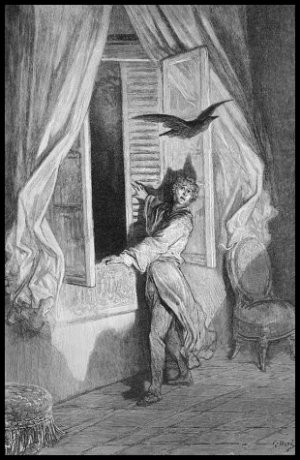

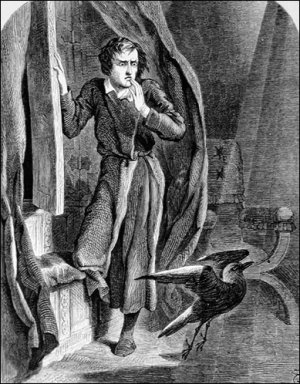

THE RAVEN

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore–

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping–rapping at my chamber door.

"’Tis some visitor," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door–

Only this and nothing more."

Ah, distinctly I remember, it was in the bleak December,

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;–vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow–sorrow for the lost Lenore–

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore–

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me–filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

"’Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door–

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door;–

This it is and nothing more."

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

"Sir," said I, "or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping–tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you"–here I opened wide the door:–

Darkness there and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering,

fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the darkness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, "Lenore!"

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, "Lenore!"

Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon I heard again a tapping, somewhat louder than before.

"Surely," said I, "surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore–

Let my heart be still a moment, and this mystery explore;–

‘Tis the wind and nothing more."

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore;

Not the least obeisance made he: not an instant stopped or stayed he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door–

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door–

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

"Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou," I said, "art sure no

craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore–

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning–little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door–

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as "Nevermore."

But the Raven, sitting lonely on that placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing further then he uttered–not a feather then he fluttered–

Till I scarcely more than muttered, "Other friends have flown before–

On the morrow he will leave me, as my hopes have flown before."

Then the bird said, "Nevermore."

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

"Doubtless," said I, "what it utters is its only stock and store,

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore–

Till the dirges of his Hope the melancholy burden bore

Of ‘Never–nevermore.’"

But the Raven still beguiling all my sad soul into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird and bust and

door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore–

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking "Nevermore."

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion’s velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o’er,

But whose velvet violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o’er,

She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

"Wretch," I cried, "thy God hath lent thee–by these angels he hath

sent thee

Respite–respite aad nepenthe from thy memories of Lenore!

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe, and forget this lost Lenore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil!–prophet still, if bird or devil!–

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted–

On this home by Horror haunted–tell me truly, I implore–

Is there– is there balm in Gilead?–tell me–tell me, I implore!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

"Prophet!" said I, "thing of evil!–prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us–by that God we both adore–

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore–

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore."

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

"Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!" I shrieked,

upstarting–

"Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken!–quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!"

Quoth the Raven, "Nevermore."

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted–nevermore!

1845

THE BELLS

I

Hear the sledges with the bells–

Silver bells!

What a world of merriment their melody foretells!

How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,

In their icy air of night!

While the stars, that oversprinkle All the heavens, seem to twinkle

With a crystalline delight;

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the tintinnabulation that so musically wells

From the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells–

From the jingling and the tinkling of the bells.

II

Hear the mellow wedding bells, Golden bells!

What a world of happiness their harmony foretells!

Through the balmy air of night

How they ring out their delight!

From the molten golden-notes,

And all in tune,

What a liquid ditty floats

To the turtle-dove that listens, while she gloats

On the moon!

Oh, from out the sounding cells,

What a gush of euphony voluminously wells!

How it swells!

How it dwells

On the future! how it tells

Of the rapture that impels

To the swinging and the ringing

Of the bells, bells, bells,

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells–

To the rhyming and the chiming of the bells!

III

Hear the loud alarum bells–

Brazen bells!

What a tale of terror now their turbulency tells!

In the startled ear of night

How they scream out their affright!

Too much horrified to speak,

They can only shriek, shriek,

Out of tune,

In a clamorous appealing to the mercy of the fire,

In a mad expostulation with the deaf and frantic fire

Leaping higher, higher, higher,

With a desperate desire,

And a resolute endeavor

Now–now to sit or never,

By the side of the pale-faced moon.

Oh, the bells, bells, bells!

What a tale their terror tells

Of Despair!

How they clang, and clash, and roar!

What a horror they outpour

On the bosom of the palpitating air!

Yet the ear it fully knows,

By the twanging,

And the clanging,

How the danger ebbs and flows;

Yet the ear distinctly tells,

In the jangling,

And the wrangling,

How the danger sinks and swells,

By the sinking or the swelling in the anger of the bells–

Of the bells–

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells–

In the clamor and the clangor of the bells!

IV

Hear the tolling of the bells–

Iron bells!

What a world of solemn thought their monody compels!

In the silence of the night,

How we shiver with affright

At the melancholy menace of their tone!

For every sound that floats

From the rust within their throats

Is a groan.

And the people–ah, the people–

They that dwell up in the steeple.

All alone,

And who tolling, tolling, tolling,

In that muffled monotone,

Feel a glory in so rolling

On the human heart a stone–

They are neither man nor woman–

They are neither brute nor human–

They are Ghouls:

And their king it is who tolls;

And he rolls, rolls, rolls,

Rolls

A paean from the bells!

And his merry bosom swells

With the paean of the bells!

And he dances, and he yells;

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the paean of the bells–

Of the bells:

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the throbbing of the bells–

Of the bells, bells, bells–

To the sobbing of the bells;

Keeping time, time, time,

As he knells, knells, knells,

In a happy Runic rhyme,

To the rolling of the bells–

Of the bells, bells, bells–

To the tolling of the bells,

Of the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells–

To the moaning and the groaning of the bells.

1849

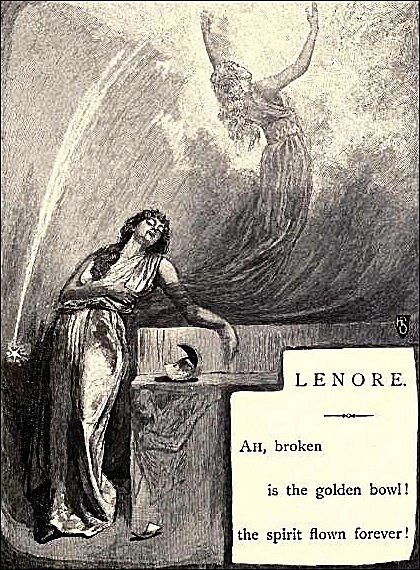

LENORE

Ah, broken is the golden bowl! the spirit flown forever!

Let the bell toll!–a saintly soul floats on the Stygian river.

And, Guy de Vere, hast thou no tear?–weep now or never more!

See! on yon drear and rigid bier low lies thy love, Lenore!

Come! let the burial rite be read–the funeral song be sung!–

An anthem for the queenliest dead that ever died so young–

A dirge for her, the doubly dead in that she died so young.

"Wretches! ye loved her for her wealth and hated her for her pride,

And when she fell in feeble health, ye blessed her–that she died!

How shall the ritual, then, be read?–the requiem how be sung

By you–by yours, the evil eye,–by yours, the slanderous tongue

That did to death the innocence that died, and died so young?"

Peccavimus; but rave not thus! and let a Sabbath song

Go up to God so solemnly the dead may feel no wrong!

The sweet Lenore hath "gone before," with Hope, that flew beside,

Leaving thee wild for the dear child that should have been thy bride–

For her, the fair and debonnaire, that now so lowly lies,

The life upon her yellow hair but not within her eyes–

The life still there, upon her hair–the death upon her eyes.

"Avaunt! to-night my heart is light. No dirge will I upraise,

But waft the angel on her flight with a paean of old days!

Let no bell toll!–lest her sweet soul, amid its hallowed mirth,

Should catch the note, as it doth float up from the damned Earth.

To friends above, from fiends below, the indignant ghost is riven–

From Hell unto a high estate far up within the Heaven–

From grief and groan to a golden throne beside the King of Heaven."

1844

.jpg)

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature