Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (01)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

Translator’s Dedication To O. H. H. and V. B. H. Who have seen and survived the Nestaroff.

BOOK I

OF THE NOTES OF SERAFINO GUBBIO CINEMATOGRAPH OPERATOR

1

I study people in their most ordinary occupations, to see if I can succeed in discovering in others what I feel that I myself lack in everything that I do: the certainty that they understand what they are doing.

At first sight it does indeed seem as though many of them had this certainty, from the way in which they look at and greet one another, hurrying to and fro in pursuit of their business or their pleasure. But afterwards, if I stop and gaze for a moment in their eyes with my own intent and silent eyes, at once they begin to take offence. Some of them, in fact, are so disturbed and perplexed that I have only to keep on gazing at them for a little longer, for them to insult or assault me.

No, go your ways in peace. This is enough for me: to know, gentlemen, that there is nothing clear or certain to you either, not even the little that is determined for you from time to time by the absolutely familiar conditions in which you are living. There is a ‘something more’ in everything. You do not wish or do not know how to see it. But the moment this something more gleams in the eyes of an idle person like myself, who has set himself to observe you, why, you become puzzled, disturbed or irritated.

I too am acquainted with the external, that is to say the mechanical framework of the life which keeps us clamorously and dizzily occupied and gives us no rest. To-day, such-and-such; this and that to be done hurrying to one place, watch in hand, so as to be in time at another.

“No, my dear fellow, thank you: I can’t!” “No, really? Lucky fellow!

I must be off….” At eleven, luncheon. The paper, the house, the office, school. … “A fine day, worse luck! But business….”

“What’s this? Ah, a funeral.” We lift our hats as we pass to the man who has made his escape. The shop, the works, the law courts….

No one has the time or the capacity to stop for a moment to consider whether what he sees other people do, what he does himself, is really the right thing, the thing that can give him that absolute certainty, in which alone a man can find rest. The rest that is given us after all the clamour and dizziness is burdened with such a load of weariness, so stunned and deafened, that it is no longer possible for us to snatch a moment for thought. With one hand we hold our heads, the other we wave in a drunken sweep.

“Let us have a little amusement!”

Yes. More wearying and complicated than our work do we find the amusements that are offered us; since from our rest we derive nothing but an increase of weariness.

I look at the women in the street, note how they are dressed, how they walk, the hats they wear on their heads; at the men, and the airs they have or give themselves; I listen to their talk, their plans; and at times it seems to me so impossible to believe in the reality of all that I see and hear, that being incapable, on the other hand, of believing that they are all doing it as a joke, I ask myself whether really all this clamorous and dizzy machinery of life, which from day to day seems to become more complicated and to move with greater speed, has not reduced the human race to such a condition of insanity that presently we must break out in fury and overthrow and destroy everything. It would, perhaps, all things considered, be so much to the good. In one respect only, though: to make a clean sweep and start afresh.

Here in this country we have not yet reached the point of witnessing the spectacle, said to be quite common in America, of men who, while engaged in carrying on their business, amid the tumult of life, fall to the ground, paralysed. But perhaps, with the help of God, we shall soon reach it. I know that all sorts of things are in preparation.

Ah, yes, the work goes on! And I, in my humble way, am one of those employed on this work ‘to provide amusement’.

I am an operator. But, as a matter of fact, being an operator, in the world in which I live and upon which I live, does not in the least mean operating. I operate nothing.

This is what I do. I set up my machine on its knock-kneed tripod. One or more stage hands, following my directions, mark out on the carpet or on the stage with a long wand and a blue pencil the limits within which the actors have to move to keep the picture in focus.

This is called ‘marking out the ground’.

The others mark it out, not I: I do nothing more than apply my eyes to the machine so that I can indicate how far it will manage to ‘take’.

When the stage is set, the producer arranges the actors on it, and outlines to them the action to be gone through.

I say to the producer:

“How many feet?”

The producer, according to the length of the scene, tells me approximately the number of feet of film that I shall need, then calls to the actors:

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

And I start turning the handle.

I might indulge myself in the illusion that, by turning the handle, I set these actors in motion, just as an organ-grinder creates the music by turning his handle. But I allow myself neither this nor any other illusion, and keep on turning until the scene is finished; then I look at the machine and inform the producer:

“Sixty feet,” or “a hundred and twenty.”

And that is all.

A gentleman, who had come out of curiosity, asked me once:

“Excuse me, but haven’t they yet discovered a way of making the camera go by itself?”

I can still see that gentleman’s face; delicate, pale, with thin, fair hair; keen, blue eyes; a pointed, yellowish beard, behind which there lurked a faint smile, that tried to appear timid and polite, but was really malicious. For by his question he meant to say to me:

“Is there any real necessity for you? What are you? A hand that turns the handle. Couldn’t they do without this hand? Couldn’t you be eliminated, replaced by some piece of machinery?”

I smiled as I answered:

“In time, Sir, perhaps. To tell you the truth, the chief quality that is required in a man of my profession is impassivity in face of the action that is going on in front of the camera. A piece of machinery, in that respect, would doubtless be better suited, and preferable to a man. But the most serious difficulty, at present, is this: where to find a machine that can regulate its movements according to the action that is going on in front of the camera. Because I, my dear Sir, do not always turn the handle at the same speed, but faster or slower as may be required. I have no doubt, however, that in time, Sir, they will succeed in eliminating me. The machine–this machine too, like all the other machines–will go by itself. But what mankind will do then, after all the machines have been taught to go by themselves, that, my dear Sir, still remains to be seen.”

(to be continued)

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (01)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

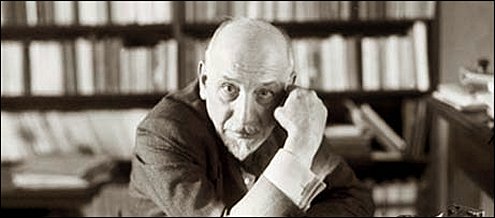

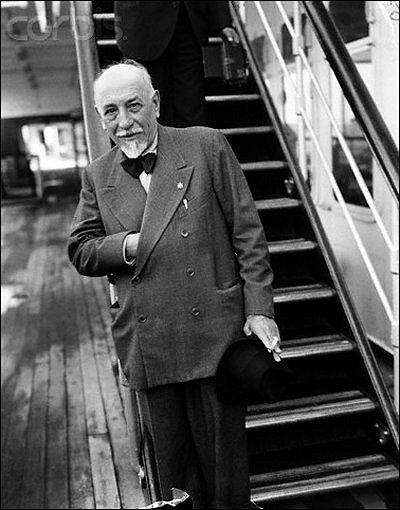

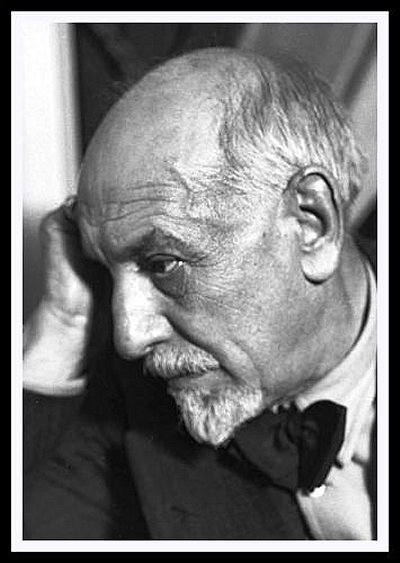

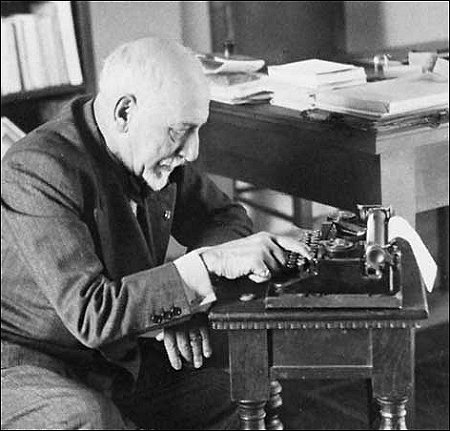

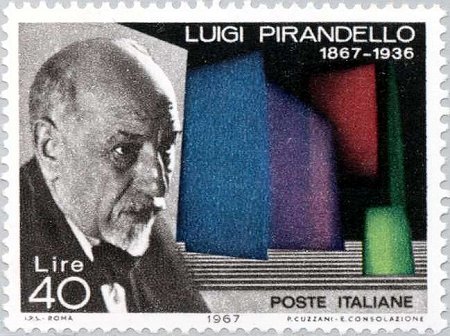

Luigi Pirandello

(1867-1936)

W a r

The passengers who had left Rome by the night express had had to stop until dawn at the small station of Fabriano in order to continue their journey by the small old-fashioned local joining the main line with Sulmona.

At dawn, in a stuffy and smoky second-class carriage in which five people had already spent the night, a bulky woman in deep mourning was hosted in—almost like a shapeless bundle. Behind her—puffing and moaning, followed her husband—a tiny man; thin and weakly, his face death-white, his eyes small and bright and looking shy and uneasy.

Having at last taken a seat he politely thanked the passengers who had helped his wife and who had made room for her; then he turned round to the woman trying to pull down the collar of her coat and politely inquired:

“Are you all right, dear?”

The wife, instead of answering, pulled up her collar again to her eyes, so as to hide her face.

“Nasty world,” muttered the husband with a sad smile.

And he felt it his duty to explain to his traveling companions that the poor woman was to be pitied for the war was taking away from her her only son, a boy of twenty to whom both had devoted their entire life, even breaking up their home at Sulmona to follow him to Rome, where he had to go as a student, then allowing him to volunteer for war with an assurance, however, that at least six months he would not be sent to the front and now, all of a sudden, receiving a wire saying that he was due to leave in three days’ time and asking them to go and see him off.

The woman under the big coat was twisting and wriggling, at times growling like a wild animal, feeling certain that all those explanations would not have aroused even a shadow of sympathy from those people who—most likely—were in the same plight as herself. One of them, who had been listening with particular attention, said:

“You should thank God that your son is only leaving now for the front. Mine has been sent there the first day of the war. He has already come back twice wounded and been sent back again to the front.”

“What about me? I have two sons and three nephews at the front,” said another passenger.

“Maybe, but in our case it is our only son,” ventured the husband.

“What difference can it make? You may spoil your only son by excessive attentions, but you cannot love him more than you would all your other children if you had any. Parental love is not like bread that can be broken to pieces and split amongst the children in equal shares. A father gives all his love to each one of his children without discrimination, whether it be one or ten, and if I am suffering now for my two sons, I am not suffering half for each of them but double…”

“True…true…” sighed the embarrassed husband, “but suppose (of course we all hope it will never be your case) a father has two sons at the front and he loses one of them, there is still one left to console him…while…”

“Yes,” answered the other, getting cross, “a son left to console him but also a son left for whom he must survive, while in the case of the father of an only son if the son dies the father can die too and put an end to his distress. Which of the two positions is worse? Don’t you see how my case would be worse than yours?”

“Nonsense,” interrupted another traveler, a fat, red-faced man with bloodshot eyes of the palest gray.

He was panting. From his bulging eyes seemed to spurt inner violence of an uncontrolled vitality which his weakened body could hardly contain.

“Nonsense, “he repeated, trying to cover his mouth with his hand so as to hide the two missing front teeth. “Nonsense. Do we give life to our own children for our own benefit?”

The other travelers stared at him in distress. The one who had had his son at the front since the first day of the war sighed: “You are right. Our children do not belong to us, they belong to the country…”

“Bosh,” retorted the fat traveler. “Do we think of the country when we give life to our children? Our sons are born because…well, because they must be born and when they come to life they take our own life with them. This is the truth. We belong to them but they never belong to us. And when they reach twenty they are exactly what we were at their age. We too had a father and mother, but there were so many other things as well…girls, cigarettes, illusions, new ties…and the Country, of course, whose call we would have answered—when we were twenty—even if father and mother had said no. Now, at our age, the love of our Country is still great, of course, but stronger than it is the love of our children. Is there any one of us here who wouldn’t gladly take his son’s place at the front if he could?”

There was a silence all round, everybody nodding as to approve.

“Why then,” continued the fat man, “should we consider the feelings of our children when they are twenty? Isn’t it natural that at their age they should consider the love for their Country (I am speaking of decent boys, of course) even greater than the love for us? Isn’t it natural that it should be so, as after all they must look upon us as upon old boys who cannot move any more and must sit at home? If Country is a natural necessity like bread of which each of us must eat in order not to die of hunger, somebody must go to defend it. And our sons go, when they are twenty, and they don’t want tears, because if they die, they die inflamed and happy (I am speaking, of course, of decent boys). Now, if one dies young and happy, without having the ugly sides of life, the boredom of it, the pettiness, the bitterness of disillusion…what more can we ask for him? Everyone should stop crying; everyone should laugh, as I do…or at least thank God—as I do—because my son, before dying, sent me a message saying that he was dying satisfied at having ended his life in the best way he could have wished. That is why, as you see, I do not even wear mourning…”

He shook his light fawn coat as to show it; his livid lip over his missing teeth was trembling, his eyes were watery and motionless, and soon after he ended with a shrill laugh which might well have been a sob.

“Quite so…quite so…” agreed the others.

The woman who, bundled in a corner under her coat, had been sitting and listening had—for the last three months—tried to find in the words of her husband and her friends something to console her in her deep sorrow, something that might show her how a mother should resign herself to send her son not even to death but to a probable danger of life. Yet not a word had she found amongst the many that had been said…and her grief had been greater in seeing that nobody—as she thought—could share her feelings.

But now the words of the traveler amazed and almost stunned her. She suddenly realized that it wasn’t the others who were wrong and could not understand her but herself who could not rise up to the same height of those fathers and mothers willing to resign themselves, without crying, not only to the departure of their sons but even to their death.

She lifted her head, she bent over from her corner trying to listen with great attention to the details which the fat man was giving to his companions about the way his son had fallen as a hero, for his King and his Country, happy and without regrets. It seemed to her that she had stumbled into a world she had never dreamt of, a world so far unknown to her, and she was so pleased to hear everyone joining in congratulating that brave father who could so stoically speak of his child’s death.

Then suddenly, just as if she had heard nothing of what had been said and almost as if waking up from a dream, she turned to the old man, asking him:

“Then…is your son really dead?”

Everyone stared at her. The old man, too, turned to look at her, fixing his great, bulging, horribly watery light gray eyes, deep in her face. For some time he tried to answer, but words failed him. He looked and looked at her, almost as if only then—at that silly, incongruous question—he had suddenly realized at last that his son was really dead—gone for ever—for ever. His face contracted, became horribly distorted, then he snatched in haste a handkerchief from his pocket and, to the amazement of everyone, broke into harrowing, heart-breaking, uncontrollable sobs.

Luigi Pirandello: War

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Luigi Pirandello

L u i g i P i r a n d e l l o

(1867-1936)

Tormenti

Quando in croce Gesú l’anima rese,

tutta, per un momento,

su la terra la vita si sospese,

sospese anche l’inferno ogni tormento.

Sisifo che per l’erta maledetta

avea sospinto il masso

fin su l’aspra del colle aguzza vetta,

donde tuttor riprecipita al basso,

fermo, lassú, starsi d’un tratto il vede:

stupefatto, in un oh!

fermo, di sasso, anch’egli resta, e fede

al prodigio prestar non sa, non può.

Si guarda attorno, una e due volte scuote

il macigno che sta;

vi siede e, con le pugna su le gote,

poi domanda a se stesso: – «E or che si fa?» –

Ma sotto, ecco, gli ruzzola il fatale

sasso di nuovo; ratto

balza egli in pie’, lo segue, e: – «Manco male! –

dice. – Almeno cosí, via, m’arrabatto». –

E, mentre sú per l’erta novamente

contro il masso si slancia,

tra le doglie piú là, Tantalo sente

gridare urlare: – «Ahi Dio! Ahi Dio! la pancia!» –

Aggirandosi come una bufera,

satollo, il poveretto,

in quella tregua momentanea s’era

di tutto quanto il suo crudel banchetto.

Ed or gemeva: – «Non lo farò piú!

Beato chi desia

e nulla ottiene mai! Grazia, Gesú!

Sia benedetta la condanna mia!» –

Leggendo la Storia

Sú, allegra, allegra, cara mia! Mi pare

che tu la prenda un po’ troppo sul serio.

Delitti, infamie, sí, senza criterio,

impudicizie da strasecolare;

ma gajo papa era Alessandro Borgia,

tranquillo e ingenuo nelle sue nequizie;

tranne quel della donna, senza vizi, e

sobrio, anzi frugale in mezzo all’orgia.

Ebbe per l’oro, è vero, anima lurca,

ma lo spendeva poi, tutto, tal quale.

Né per un papa infin la vedo male

che andasse a caccia vestito alla turca.

Di piú d’un figlio con Vannozza reo,

diede a Vannozza sua piú d’un marito;

ma l’ultimo, il Canal, bravo erudito:

il Polizian gli dedicò l’Orfeo,

Quanti vitelli con moderna clava

accoppa l’uomo e se li mangia? Orbene,

papa Alessandro, accoppator dabbene,

i suoi nemici, non se li mangiava.

Dunque, non mi seccar! Parole amare,

serio comento a questa fantocciata

della vita? Va’ là. Carta sprecata.

Ridi meglio, narrando, e lascia fare.

Primavera dei Terrazzi

La mia vicina, sul mattin d’aprile,

compresa ancora del tepor del letto,

esce al terrazzo, e al sol primaverile

spiega i tesori del ricolmo petto.

Ella ha piú grazia, la vicina, in quella

acconciatura che le cangia aspetto:

un camicino bianco e una gonnella

di panno lano oscura. La saluto

dal mio poggiolo dirimpetto, ed ella,

lieve inchinando il capo riccioluto,

mi risponde; poi viene al pilastrino,

su cui ride snasato un fauno arguto,

e dice: – «Come mai, caro vicino?

siete voi? sogno ancora? o com’è andata?

qual gallo v’ha cantato il mattutino?» –

Cosí, tra i fior, su la balaustrata,

dei vasi ben disposti e con amore

coltivati da lei lungo l’annata,

un grande anch’ella pare e vivo fiore;

anzi, lei sola, un fiore. A quel giardino,

giro giro, che calci di gran cuore

darei! parmi ogni vaso un cervellino

di moderno romantico poeta

che levi dal suo fango un inno fino

tra il cessin le pillaccole e la creta

per dir che piú non ama e piú non spera

alla stagion che tutto il mondo allieta.

Oh dei terrazzi magra primavera,

sciocca di nuove rime fioritura!

Mi duol che voi, maestra giardiniera,

ve ne prendiate cosí assidua cura.

Codesti fiori dall’olezzo ingrato

non vi sembrano sforzi di natura?

Due tartarughe, intanto, senza fiato,

s’inseguono sui pie’ sbiechi, in amore,

raspando il piano d’asfalto bruciato.

Cara vicina, fatemi il favore

di rivoltarle su la scaglia al sole:

non hanno alcun riguardo, alcun pudore,

brutte rocciose sceme bestiole;

sono lí lí per fare atto villano,

mentre che noi facciam solo parole:

le vedremo armeggiar nel vuoto, invano.

Luigi Pirandello: Poesia

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Luigi Pirandello, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

L u i g i P i r a n d e l l o

(1867-1936)

LE NUBI E LA LUNA

La nuvolaglia va stracca, raminga,

e or si sparpaglia ed ora si raduna,

quasi un soffio aspettando che la spinga

a far del bene altrove. Tutta bruna

d’acqua la terra e paga s’addormenta,

e vien dal colle sú, grande, la Luna.

Sale pian piano, come diva intenta

a vigilare, e a sé le nubi chiama.

Or questa or quella le si appressa lenta,

prende consiglio, si dirada, sciama

al lume, si raddensa, s’allontana…

Che mai la Luna con le nubi trama?

Quatta musando se ne sta la rana.

Forse ha compreso ch’ora qui ripiove?

Salta in un borro là d’acqua piovana.

Ma van le nubi a far del bene altrove.

Poem of the week

November 9, 2008

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Luigi Pirandello, Pirandello, Luigi

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature