Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

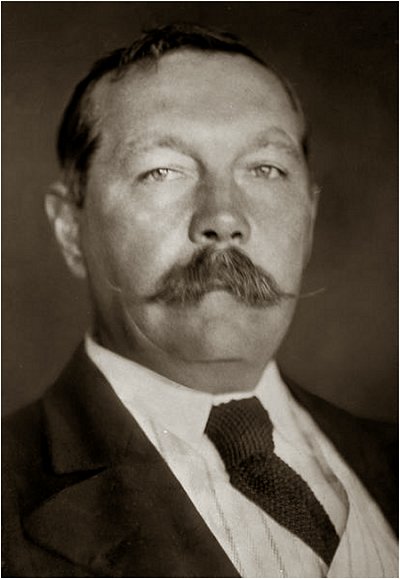

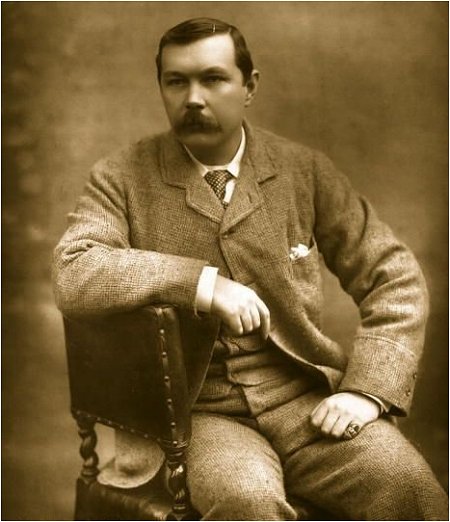

Arthur Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

A Tragedy

Who’s that walking on the moorland?

Who’s that moving on the hill?

They are passing ‘mid the bracken,

But the shadows grow and blacken

And I cannot see them clearly on the hill.

Who’s that calling on the moorland?

Who’s that crying on the hill?

Was it bird or was it human,

Was it child, or man, or woman,

Who was calling so sadly on the hill?

Who’s that running on the moorland?

Who’s that flying on the hill?

He is there — and there again,

But you cannot see him plain,

For the shadow lies so darkly on the hill.

What’s that lying in the heather?

What’s that lurking on the hill?

My horse will go no nearer,

And I cannot see it clearer,

But there’s something that is lying on the hill.

.jpg)

Arthur Conan Doyle poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan

Arthur Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

The Passing

IT was the hour of dawn,

When the heart beats thin and small,

The window glimmered grey,

Framed in a shadow wall.

And in the cold sad light

Of the early morningtide,

The dear dead girl came back

And stood by his beside.

The girl he lost came back:

He saw her flowing hair;

It flickered and it waved

Like a breath in frosty air.

As in a steamy glass,

Her face was dim and blurred;

Her voice was sweet and thin,

Like the calling of a bird.

‘You said that you would come,

You promised not to stay;

And I have waited here,

To help you on the way.

‘I have waited on,

But still you bide below;

You said that you would come,

And oh, I want you so!

‘For half my soul is here,

And half my soul is there,

When you are on the earth

And I am in the air.

‘But on your dressing-stand

There lies a triple key;

Unlock the little gate

Which fences you from me.

‘Just one little pang,

Just one throb of pain,

And then your weary head

Between my breasts again.’

In the dim unhomely light

Of the early morningtide,

He took the triple key

And he laid it by his side.

A pistol, silver chased,

An open hunting knife,

A phial of the drug

Which cures the ill of life.

He looked upon the three,

And sharply drew his breath:

‘Now help me, oh my love,

For I fear this cold grey death.’

She bent her face above,

She kissed him and she smiled;

She soothed him as a mother

May sooth a frightened child.

‘Just that little pang, love,

Just a throb of pain,

And then your weary head

Between my breasts again.’

He snatched the pistol up,

He pressed it to his ear;

But a sudden sound broke in,

And his skin was raw with fear.

He took the hunting knife,

He tried to raise the blade;

It glimmered cold and white,

And he was sore afraid.

He poured the potion out,

But it was thick and brown;

His throat was sealed against it,

And he could not drain it down.

He looked to her for help,

And when he looked — behold!

His love was there before him

As in the days of old.

He saw the drooping head,

He saw the gentle eyes;

He saw the same shy grace of hers

He had been wont to prize.

She pointed and she smiled,

And lo! he was aware

Of a half-lit bedroom chamber

And a silent figure there.

A silent figure lying

A-sprawl upon a bed,

With a silver-mounted pistol

Still clotted to his head.

And as he downward gazed,

Her voice came full and clear,

The homely tender voice

Which he had loved to hear:

‘The key is very certain,

The door is sealed to none.

You did it, oh, my darling!

And you never knew it done.

‘When the net was broken,

You thought you felt its mesh;

You carried to the spirit

The troubles of the flesh.

‘And are you trembling still, dear?

Then let me take your hand;

And I will lead you outward

To a sweet and restful land.

‘You know how once in London

I put my griefs on you;

But I can carry yours now–

Most sweet it is to do!

‘Most sweet it is to do, love,

And very sweet to plan

How I, the helpless woman,

Can help the helpful man.

‘But let me see you smiling

With the smile I know so well;

Forget the world of shadows,

And the empty broken shell.

‘It is the worn-out garment

In which you tore a rent;

You tossed it down, and carelessly

Upon your way you went.

‘It is not you, my sweetheart,

For you are here with me.

That frame was but the promise of

The thing that was to be–

‘A tuning of the choir

Ere the harmonies begin;

And yet it is the image

Of the subtle thing within.

‘There’s not a trick of body,

There’s not a trait of mind,

But you bring it over with you,

Ethereal, refined,

‘But still the same; for surely

If we alter as we die,

You would be you no longer,

And I would not be I.

‘I might be an angel,

But not the girl you knew;

You might be immaculate,

But that would not be you.

‘And now I see you smiling,

So, darling, take my hand;

And I will lead you outward

To a sweet and pleasant land,

‘Where thought is clear and nimble,

Where life is pure and fresh,

Where the soul comes back rejoicing

From the mud-bath of the flesh

‘But still that soul is human,

With human ways, and so

I love my love in spirit,

As I loved him long ago.’

So with hands together

And fingers twining tight,

The two dead lovers drifted

In the golden morning light.

But a grey-haired man was lying

Beneath them on a bed,

With a silver-mounted pistol

Still clotted to his head.

.jpg)

Arthur Conan Doyle poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan

Arthur Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

The Frontier Line

What marks the frontier line? Thou man of India, say! Is it the Himalayas sheer, The rocks and valleys of Cashmere, Or Indus as she seeks the south From Attoch to the fivefold mouth? ‘Not that! Not that!’ Then answer me, I pray! What marks the frontier line?

What marks the frontier line? Thou man of Burmah, speak! Is it traced from Mandalay, And down the marches of Cathay, From Bhamo south to Kiang-mai, And where the buried rubies lie? ‘Not that! Not that!’ Then tell me what I seek: What marks the frontier line?

What marks the frontier line? Thou Africander, say! Is it shown by Zulu kraal, By Drakensberg or winding Vaal, Or where the Shire waters seek Their outlet east at Mozambique? ‘Not that! Not that! There is a surer way To mark the frontier line.’

What marks the frontier line? Thou man of Egypt, tell! Is it traced on Luxor’s sand, Where Karnak’s painted pillars stand, Or where the river runs between The Ethiop and Bishareen? ‘Not that! Not that! By neither stream nor well We mark the frontier line.

‘But be it east or west, One common sign we bear, The tongue may change, the soil, the sky, But where your British brothers lie, The lonely cairn, the nameless grave, Still fringe the flowing Saxon wave. ‘Tis that! ‘Tis where THEY lie–the men who placed it there, That marks the frontier line.’

.jpg)

Arthur Conan Doyle poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Archive C-D, Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan

Arthur Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

Pennarby Mine

Pennarby shaft is dark and steep,

Eight foot wide, eight hundred deep.

Stout the bucket and tough the cord,

Strong as the arm of Winchman Ford.

‘Never look down!

Stick to the line!’

That was the saying at Pennarby mine.

A stranger came to Pennarby shaft.

Lord, to see how the miners laughed!

White in the collar and stiff in the hat,

With his patent boots and his silk cravat,

Picking his way,

Dainty and fine,

Stepping on tiptoe to Pennarby mine.

Touring from London, so he said.

Was it copper they dug for? or gold? or lead?

Where did they find it? How did it come?

If he tried with a shovel might he get some?

Stooping so much

Was bad for the spine;

And wasn’t it warmish in Pennarby mine?

‘Twas like two worlds that met that day–

The world of work and the world of play;

And the grimy lads from the reeking shaft

Nudged each other and grinned and chaffed.

‘Got ’em all out!’

‘A cousin of mine!’

So ran the banter at Pennarby mine.

And Carnbrae Bob, the Pennarby wit,

Told him the facts about the pit:

How they bored the shaft till the brimstone smell

Warned them off from tapping — well,

He wouldn’t say what,

But they took it as sign

To dig no deeper in Pennarby mine.

Then leaning over and peering in,

He was pointing out what he said was tin

In the ten-foot lode — a crash! a jar!

A grasping hand and a splintered bar.

Gone in his strength,

With the lips that laughed–

Oh, the pale faces round Pennarby shaft!

Far down on a narrow ledge,

They saw him cling to the crumbling edge.

‘Wait for the bucket! Hi, man! Stay!

That rope ain’t safe! It’s worn away!

He’s taking his chance,

Slack out the line!

Sweet Lord be with him! ‘cried Pennarby mine.

‘He’s got him! He has him! Pull with a will!

Thank God! He’s over and breathing still.

And he — Lord’s sakes now! What’s that? Well!

Blowed if it ain’t our London swell.

Your heart is right

If your coat is fine:

Give us your hand! ‘cried Pennarby mine.

Arthur Conan Doyle poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature