Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

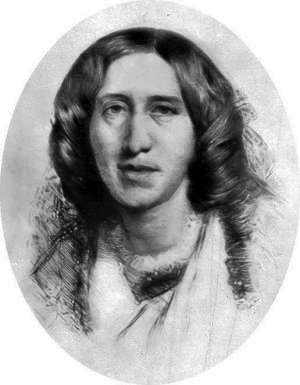

G e o r g e E l i o t

(Mary Ann Evans, 1819 – 1880)

Sweet Evenings Come and Go, Love

"La noche buena se viene,

La noche buena se va,

Y nosotros nos iremos

Y no volveremos mas."

— Old Villancico.

Sweet evenings come and go, love,

They came and went of yore:

This evening of our life, love,

Shall go and come no more.

When we have passed away, love,

All things will keep their name;

But yet no life on earth, love,

With ours will be the same.

The daisies will be there, love,

The stars in heaven will shine:

I shall not feel thy wish, love,

Nor thou my hand in thine.

A better time will come, love,

And better souls be born:

I would not be the best, love,

To leave thee now forlorn.

.jpg)

George Eliot poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Eliot, George

George Eliot

(Mary Ann Evans, 1819 – 1880)

Blue Wings

Warm whisp’ring through the slender olive leaves

Came to me a gentle sound,

Whis’pring of a secret found

In the clear sunshine ‘mid the golden sheaves:

Said it was sleeping for me in the morn,

Called it gladness, called it joy,

Drew me on "Come hither, boy."

To where the blue wings rested on the corn.

I thought the gentle sound had whispered true

Thought the little heaven mine,

Leaned to clutch the thing divine,

And saw the blue wings melt within the blue!

Bright, o bright Fedalma

Maiden crowned with glossy blackness,

Lithe as panther forest-roaming,

Long-armed Naiad when she dances

On a stream of ether floating,

Bright, o bright Fedalma!

Form all curves like softness drifted,

Wave-kissed marble roundly dimpling,

Far-off music slowly wingèd,

Gently rising, gently sinking,

Bright, o bright Fedalma!

Pure as rain-tear on a rose-leaf,

Cloud high born in noonday spotless

Sudden perfect like the dew-bead,

Gem of earth and sky begotten,

Bright, o bright Fedalma!

Beauty has no mortal father,

Holy light her form engendered,

Out of tremor yearning, gladness,

Presage sweet, and joy remembered,

Child of light! Child of light!

Child of light, Fedalma!

Came a pretty maid

Came a pretty maid

By the moon’s pure light . . .

Loved me well, she said,

Eyes with tears all bright,

A pretty maid.

But too late she strayed,

Moonlight pure was there . . .

She was nought but shade,

Hiding the more fair,

The heav’nly maid.

.jpg)

George Eliot poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Eliot, George

.jpg)

G e o r g e E l i o t

(Mary Ann Evans, 1819 – 1880)

Mid My Gold-Brown Curls

‘Mid my gold-brown curls

There twined a silver hair:

I plucked it idly out

And scarcely knew ’twas there.

Coiled in my velvet sleeve it lay

And like a serpent hissed:

"Me thou canst pluck & fling away,

One hair is lightly missed;

But how on that near day

When all the wintry army muster in array?"

Roses

You love the roses – so do I. I wish

The sky would rain down roses, as they rain

From off the shaken bush. Why will it not?

Then all the valley would be pink and white

And soft to tread on. They would fall as light

As feathers, smelling sweet; and it would be

Like sleeping and like waking, all at once!

.jpg)

George Eliot poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Eliot, George

G e o r g e E l i o t

(Mary Ann Evans, 1819 – 1880)

Brother and Sister

I.

I cannot choose but think upon the time

When our two lives grew like two buds that kiss

At lightest thrill from the bee’s swinging chime,

Because the one so near the other is.

He was the elder and a little man

Of forty inches, bound to show no dread,

And I the girl that puppy-like now ran,

Now lagged behind my brother’s larger tread.

I held him wise, and when he talked to me

Of snakes and birds, and which God loved the best,

I thought his knowledge marked the boundary

Where men grew blind, though angels knew the rest.

If he said "Hush!" I tried to hold my breath;

Wherever he said "Come!" I stepped in faith.

II.

Long years have left their writing on my brow,

But yet the freshness and the dew-fed beam

Of those young mornings are about me now,

When we two wandered toward the far-off stream

With rod and line. Our basket held a store

Baked for us only, and I thought with joy

That I should have my share, though he had more,

Because he was the elder and a boy.

The firmaments of daisies since to me

Have had those mornings in their opening eyes,

The bunchèd cowslip’s pale transparency

Carries that sunshine of sweet memories,

And wild-rose branches take their finest scent

From those blest hours of infantine content.

III.

Our mother bade us keep the trodden ways,

Stroked down my tippet, set my brother’s frill,

Then with the benediction of her gaze

Clung to us lessening, and pursued us still

Across the homestead to the rookery elms,

Whose tall old trunks had each a grassy mound,

So rich for us, we counted them as realms

With varied products: here were earth-nuts found,

And here the Lady-fingers in deep shade;

Here sloping toward the Moat the rushes grew,

The large to split for pith, the small to braid;

While over all the dark rooks cawing flew,

And made a happy strange solemnity,

A deep-toned chant from life unknown to me.

IV.

Our meadow-path had memorable spots:

One where it bridged a tiny rivulet,

Deep hid by tangled blue Forget-me-nots;

And all along the waving grasses met

My little palm, or nodded to my cheek,

When flowers with upturned faces gazing drew

My wonder downward, seeming all to speak

With eyes of souls that dumbly heard and knew.

Then came the copse, where wild things rushed unseen,

And black-scathed grass betrayed the past abode

Of mystic gypsies, who still lurked between

Me and each hidden distance of the road.

A gypsy once had startled me at play,

Blotting with her dark smile my sunny day.

V.

Thus rambling we were schooled in deepest lore,

And learned the meanings that give words a soul,

The fear, the love, the primal passionate store,

Whose shaping impulses make manhood whole.

Those hours were seed to all my after good;

My infant gladness, through eye, ear, and touch,

Took easily as warmth a various food

To nourish the sweet skill of loving much.

For who in age shall roam the earth and find

Reasons for loving that will strike out love

With sudden rod from the hard year-pressed mind?

Were reasons sown as thick as stars above,

‘Tis love must see them, as the eye sees light:

Day is but Number to the darkened sight.

VI.

Our brown canal was endless to my thought;

And on its banks I sat in dreamy peace,

Unknowing how the good I loved was wrought,

Untroubled by the fear that it would cease.

Slowly the barges floated into view

Rounding a grassy hill to me sublime

With some Unknown beyond it, whither flew

The parting cuckoo toward a fresh spring time.

The wide-arched bridge, the scented elder-flowers,

The wondrous watery rings that died too soon,

The echoes of the quarry, the still hours

With white robe sweeping-on the shadeless noon,

Were but my growing self, are part of me,

My present Past, my root of piety.

VII.

Those long days measured by my little feet

Had chronicles which yield me many a text;

Where irony still finds an image meet

Of full-grown judgments in this world perplext.

One day my brother left me in high charge,

To mind the rod, while he went seeking bait,

And bade me, when I saw a nearing barge,

Snatch out the line lest he should come too late.

Proud of the task, I watched with all my might

For one whole minute, till my eyes grew wide,

Till sky and earth took on a strange new light

And seemed a dream-world floating on some tide —

A fair pavilioned boat for me alone

Bearing me onward through the vast unknown.

VIII.

But sudden came the barge’s pitch-black prow,

Nearer and angrier came my brother’s cry,

And all my soul was quivering fear, when lo!

Upon the imperilled line, suspended high,

A silver perch! My guilt that won the prey,

Now turned to merit, had a guerdon rich

Of songs and praises, and made merry play,

Until my triumph reached its highest pitch

When all at home were told the wondrous feat,

And how the little sister had fished well.

In secret, though my fortune tasted sweet,

I wondered why this happiness befell.

"The little lass had luck," the gardener said:

And so I learned, luck was with glory wed.

IX.

We had the self-same world enlarged for each

By loving difference of girl and boy:

The fruit that hung on high beyond my reach

He plucked for me, and oft he must employ

A measuring glance to guide my tiny shoe

Where lay firm stepping-stones, or call to mind

"This thing I like my sister may not do,

For she is little, and I must be kind."

Thus boyish Will the nobler mastery learned

Where inward vision over impulse reigns,

Widening its life with separate life discerned,

A Like unlike, a Self that self restrains.

His years with others must the sweeter be

For those brief days he spent in loving me.

X.

His sorrow was my sorrow, and his joy

Sent little leaps and laughs through all my frame;

My doll seemed lifeless and no girlish toy

Had any reason when my brother came.

I knelt with him at marbles, marked his fling

Cut the ringed stem and make the apple drop,

Or watched him winding close the spiral string

That looped the orbits of the humming top.

Grasped by such fellowship my vagrant thought

Ceased with dream-fruit dream-wishes to fulfil;

My aëry-picturing fantasy was taught

Subjection to the harder, truer skill

That seeks with deeds to grave a thought-tracked line,

And by "What is," "What will be" to define.

XI.

School parted us; we never found again

That childish world where our two spirits mingled

Like scents from varying roses that remain

One sweetness, nor can evermore be singled.

Yet the twin habit of that early time

Lingered for long about the heart and tongue:

We had been natives of one happy clime

And its dear accent to our utterance clung.

Till the dire years whose awful name is Change

Had grasped our souls still yearning in divorce,

And pitiless shaped them in two forms that range

Two elements which sever their life’s course.

But were another childhood-world my share,

I would be born a little sister there.

George Eliot poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Eliot, George

George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans)

(1819-1880)

MOTHER AND POET

Dead! one of them shot by the sea in the east,

And one of them shot in the west by the sea.

Dead! both my boys! When you sit at the feast

And are wanting a great song for Italy free,

Let none look at me!

Yet I was a poetess only last year,

And good at my art for a woman, men said,

But this woman, this, who is agonized here,

The east sea and west sea rhyme on in her head

Forever instead.

What art can woman be good at? Oh, vain!

What art is she good at, but hurting her breast

With the milk-teeth of babes, and a smile at the pain?

Ah, boys, how you hurt! you were strong as you pressed,

And I proud by that test.

What’s art for a woman? To hold on her knees

Both darlings! to feel all their arms round her throat

Cling, strangle a little! To sew by degrees,

And ‘broider the long clothes and neat little coat!

To dream and to dote.

To teach them . . . It stings there. I made them indeed

Speak plain the word ‘country.’ I taught them, no doubt,

That a country’s a thing men should die for at need.

I prated of liberty, rights, and about

The tyrant turned out.

And when their eyes flashed, oh, my beautiful eyes!

I exulted! nay, let them go forth at the wheels

Of the guns, and denied not. But then the surprise,

When one sits quite alone! Then one weeps, then one kneels!

–God! how the house feels.

At first happy news came, in gay letters moiled

With my kisses, of camp-life and glory, and how

They both loved me, and soon, coming home to be spoiled,

In return would fan off every fly from my brow

With their green laurel bough.

Then was triumph at Turin. ‘Ancona was free!’

And some one came out of the cheers in the street,

With a face pale as stone to say something to me.

My Guido was dead! I fell down at his feet

While they cheered in the street.

I bore it–friends soothed me: my grief looked sublime

As the ransom of Italy. One boy remained

To be leant on and walked with, recalling the time

When the first grew immortal, while both of us strained

To the height he had gained.

And letters still came–shorter, sadder, more strong,

Write now but in one hand. I was not to faint,

One loved me for two . . . would be with me ere long,

And ‘Viva Italia’ he died for, our saint,

Who forbids our complaint.

Dead! One of them shot by the sea in the east,

And one of them shot in the West by the sea: p2.jpg}

My Nanni would add, ‘he was safe and aware

Of a presence that turned off the balls . . . was imprest

It was Guido himself, who knew what I could bear,

And how ’twas impossible, quite dispossessed,

To live on for the rest.’

On which, without pause, up the telegraph line,

Swept smoothly the next news from Gaeta–Shot.

Tell his mother. Ah, ah! ‘his,’ ‘their’ mother: not ‘mine.’

No voice says ‘ my mother’ again to me. What!

You think Guido forgot?

Are souls straight so happy that, dizzy with Heaven,

They drop earth’s affection, conceive not of woe?

I think not. Themselves were too lately forgiven

Through that Love and Sorrow which reconciled so

The Above and Below.

O Christ of the seven wounds, who look’dst through the dark

To the face of thy mother! consider, I pray,

How we common mothers stand desolate, mark,

Whose sons, not being Christs, die with eyes turned away,

And no last word to say!

Both boys dead! but that’s out of nature. We all

Have been patriots, yet each house must always keep one.

‘Twere imbecile hewing out roads to a wall,

And when Italy’s made, for what end is it done

If we have not a son?

Ah! ah! ah! when Gaeta’s taken, what then?

When the fair, wicked queen sits no more at her sport

Of the fire-balls of death crashing souls out of men?

When your guns of Cavalli, with final retort,

Have cut the game short–

When Venice and Rome keep their new jubilee,

When your flag takes all Heaven for its white, green, and red,

When you have your country from mountain to sea,

When King Victor has Italy’s crown on his head,

(And I have my dead)

What then? Do not mock me! Ah, ring your bells low!

And burn your lights faintly. My country is there,

Above the star pricked by the last peak of snow.

My Italy’s there–with my brave civic Pair,

To disfranchise despair.

Forgive me. Some women bear children in strength,

And bite back the cry of their pain in self-scorn,

But the birth-pangs of nations will wring us at length

Into wail such as this! and we sit on forlorn

When the man-child is born.

Dead! one of them shot by the sea in the west!

And one of them shot in the east by the sea!

Both! both my boys! If, in keeping the feast,

You want a great song for your Italy free,

Let none look at me!

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Eliot, George

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature