Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

1936: Dmitri Shostakovich, just thirty years old, reckons with the first of three conversations with power that will irrevocably shape his life.

Stalin, hitherto a distant figure, has suddenly denounced the young composer’s latest opera. Certain he will be exiled to Siberia (or, more likely, shot dead on the spot), Shostakovich reflects on his predicament, his personal history, his parents, his daughter—all of those hanging in the balance of his fate. And though a stroke of luck prevents him from becoming yet another casualty of the Great Terror, he will twice more be swept up by the forces of despotism: coerced into praising the Soviet state at a cultural conference in New York in 1948, and finally bullied into joining the Party in 1960. All the while, he is compelled to constantly weigh the specter of power against the integrity of his music. An extraordinary portrait of a relentlessly fascinating man, The Noise of Time is a stunning meditation on the meaning of art and its place in society.

Stalin, hitherto a distant figure, has suddenly denounced the young composer’s latest opera. Certain he will be exiled to Siberia (or, more likely, shot dead on the spot), Shostakovich reflects on his predicament, his personal history, his parents, his daughter—all of those hanging in the balance of his fate. And though a stroke of luck prevents him from becoming yet another casualty of the Great Terror, he will twice more be swept up by the forces of despotism: coerced into praising the Soviet state at a cultural conference in New York in 1948, and finally bullied into joining the Party in 1960. All the while, he is compelled to constantly weigh the specter of power against the integrity of his music. An extraordinary portrait of a relentlessly fascinating man, The Noise of Time is a stunning meditation on the meaning of art and its place in society.

Julian Barnes is the author of twenty previous books. He has received the Man Booker Prize, the Somerset Maugham Award, the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, the David Cohen Prize for Literature and the E. M. Forster Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters; in France, the Prix Médicis and the Prix Femina; and in Austria, the State Prize for European Literature. In 2004 he was named Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture. His work has been translated into more than forty languages. He lives in London.

One of the Best Books of the Year: San Francisco Chronicle

“This story is truly amazing . . . an arc of human degradation without violence (the threat of violence, of course, everywhere). . . . The whole Kafka madhouse brought to life.”—Jeremy Denk, The New York Times Book Review

The Noise of Time

A Novel

By Julian Barnes

Part of Vintage International

Literary Fiction

Paperback

Publisher Penguin Random House

June 2017,

224 Pages

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Dmitri Shostakovich, Julian Barnes, The Art of Reading

“Wie viel Leben steckt in vier Wänden? Welche Erinnerungen haften an Böden, Fenstern und Türen?

Wer in einer Wohnung lebt, lebt immer auch in einem Erinnerungsort, in einem Geschichtsraum. Und wenn schon eine Wohnung so viel Geschichten bietet, was hat dann erst ein ganzes Haus zu sagen? In ihrem Debütroman „Eine kurze Chronik des allmählichen Verschwindens“ ringt Juliana Kálnay um einen anderen, einen fantastischen Blick auf die Welt. Ein Mann wird zu einem Baum, eine alte Frau spürt wie sich die Räume bei Kälte zusammenziehen, ein ganzes Haus lebt unter dem Gesetz des Unwirklichen. In feinen, leicht verschwommenen Vignetten erzählt Kálnay auf den Spuren des magischen Realismus vom Wundern und Träumen dieser Hausbewohner. Es ist ein Buch, in dem man sich herrlich verlieren kann. Und das große Lust macht auf die Welt des Surrealen.”

Wer in einer Wohnung lebt, lebt immer auch in einem Erinnerungsort, in einem Geschichtsraum. Und wenn schon eine Wohnung so viel Geschichten bietet, was hat dann erst ein ganzes Haus zu sagen? In ihrem Debütroman „Eine kurze Chronik des allmählichen Verschwindens“ ringt Juliana Kálnay um einen anderen, einen fantastischen Blick auf die Welt. Ein Mann wird zu einem Baum, eine alte Frau spürt wie sich die Räume bei Kälte zusammenziehen, ein ganzes Haus lebt unter dem Gesetz des Unwirklichen. In feinen, leicht verschwommenen Vignetten erzählt Kálnay auf den Spuren des magischen Realismus vom Wundern und Träumen dieser Hausbewohner. Es ist ein Buch, in dem man sich herrlich verlieren kann. Und das große Lust macht auf die Welt des Surrealen.”

So begründet die Jury – Jana Hensel (Autorin), Ursula März (Die Zeit), Daniel Fiedler (Redaktionsleiter ZDF Kultur Berlin) Simon Strauß (FAZ) und Volker Weidermann (Das Literarische Quartett, Der Spiegel – ihre Entscheidung.

Juliana Kálnay erzählt mit Aberwitz und aus vielen Perspektiven, es ist ein Stimmengewirr, ein Puzzle, das sich nach und nach zu einem dichten Bild fügt. Die Charaktere – Bewohner eines rätselhaften Hauses – versuchen, sich einen Reim auf die Dinge des Lebens zu machen, sich selbst und die anderen zu verstehen, tappen aber oft im Dunklen. Kálnays magischer Realismus hält die Handlung in der Schwebe, ohne ins Phantastische abzuheben, das Haus verbindet alle Elemente im Roman.

Der aspekte-Literaturpreis wird in diesem Jahr zum 39. Mal vergeben. Er ist mit 10.000 Euro dotiert und die bedeutendste Auszeichnung für deutschsprachige Erstlingsprosa. Die Preisverleihung findet am Donnerstag, 12. Oktober 2017, 11:30 Uhr im Rahmen der Frankfurter Buchmesse auf dem Blauen Sofa am ZDF-Stand statt.

Juliana Kálnay, geboren 1988 in Hamburg, wuchs zunächst in Köln und dann in Málaga auf. Sie veröffentlichte in deutsch- und spanischsprachigen Anthologien und Zeitschriften und erhielt das Arbeitsstipendium Literatur der Kulturstiftung des Landes Schleswig-Holstein 2016. Sie lebt und schreibt in Kiel. »Eine kurze Chronik des allmählichen Verschwindens« ist ihr erster Roman.

Juliana Kálnay

Eine kurze Chronik des allmählichen Verschwindens

Quartbuch. 2017

192 Seiten. 13 x 21 cm.

Gebunden mit Schutzumschlag

Buch €20,–

ISBN 978-3-8031-3284-0

Klaus Wagenbach Verlag

(www.wagenbach.de)

Ein fantastischer Blick auf die Welt

Der aspekte-Literaturpreis 2017 geht an Juliana Kálnay

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Literary Events, Nachrichten aus Berlin, The Art of Reading

Kazuo Ishiguro was born on November 8, 1954 in Nagasaki, Japan.The family moved to the United Kingdom when he was five years old; he returned to visit his country of birth only as an adult.

In the late 1970s, Ishiguro graduated in English and Philosophy at the University of Kent, and then went on to study Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia.

In the late 1970s, Ishiguro graduated in English and Philosophy at the University of Kent, and then went on to study Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia.

Kazuo Ishiguro has been a full-time author ever since his first book, “A Pale View of Hills” (1982). Both his first novel and the subsequent one, “An Artist of the Floating World” (1986) take place in Nagasaki a few years after the Second World War. The themes Ishiguro is most associated with are already present here: memory, time, and self-delusion. This is particularly notable in his most renowned novel, “The Remains of the Day” (1989), which was turned into film with Anthony Hopkins acting as the duty-obsessed butler Stevens.

Ishiguro’s writings are marked by a carefully restrained mode of expression, independent of whatever events are taking place. At the same time, his more recent fiction contains fantastic features. With the dystopian work “Never Let Me Go” (2005), Ishiguro introduced a cold undercurrent of science fiction into his work. In this novel, as in several others, we also find musical influences. A striking example is the collection of short stories titled “Nocturnes: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall” (2009), where music plays a pivotal role in depicting the characters’ relationships. In his latest novel, “The Buried Giant” (2015), an elderly couple go on a road trip through an archaic English landscape, hoping to reunite with their adult son, whom they have not seen for years. This novel explores, in a moving manner, how memory relates to oblivion, history to the present, and fantasy to reality.

Ishiguro’s writings are marked by a carefully restrained mode of expression, independent of whatever events are taking place. At the same time, his more recent fiction contains fantastic features. With the dystopian work “Never Let Me Go” (2005), Ishiguro introduced a cold undercurrent of science fiction into his work. In this novel, as in several others, we also find musical influences. A striking example is the collection of short stories titled “Nocturnes: Five Stories of Music and Nightfall” (2009), where music plays a pivotal role in depicting the characters’ relationships. In his latest novel, “The Buried Giant” (2015), an elderly couple go on a road trip through an archaic English landscape, hoping to reunite with their adult son, whom they have not seen for years. This novel explores, in a moving manner, how memory relates to oblivion, history to the present, and fantasy to reality.

Apart from his eight books, Ishiguro has also written scripts for film and television.

# More info website Nobelprize

The Nobel Prize in Literature for 2017 to English author Kazuo Ishiguro

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, Archive I-J, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Awards & Prizes, Kazuo Ishiguro, The Art of Reading

Johan Bertus Wouter Polak (1928-1992) was een legendarische en extravagante uitgever, essayist, bibliofiel, vertaler en mecenas.

Johan Bertus Wouter Polak (1928-1992) was een legendarische en extravagante uitgever, essayist, bibliofiel, vertaler en mecenas.

Hij groeide op in ‘een zeer liberaal joods milieu met sterk atheïstische en sociaaldemocratische inslag’. Dit ogenschijnlijk idyllische bestaan werd bruut verstoord door de vroege dood van Johans vader en de Duitse bezetting vlak daarna. Deze ingrijpende gebeurtenissen en de verhouding met zijn moeder bepaalden voor een groot deel Polaks verdere leven.

De drama’s uit zijn jeugd worden door Hilberdink in verband gebracht met de oprichting van uitgeverij Polak & Van Gennep in 1962. Hij gaf op fraaie wijze het werk uit van onder anderen P.C. Boutens, J.H. Leopold, Herman Gorter en J.C. Bloem. En dat van Gerard Reve, die hij van alle naoorlogse auteurs het meest bewonderde en met wie hij een uiterst complexe verhouding kreeg.

Daarnaast begon Polak in 1966 de al even vermaarde Athenaeum Boekhandel op het Spui in Amsterdam. Het werd een centrum van activiteiten, zowel politiek als literair, en Johan werd een bekende Amsterdammer.

Uitvoerig komt ook Polaks rol aan de orde in de emancipatie van homoseksuelen en de strijd tegen het antisemitisme.

Zijn persoonlijke seksuele bevrijding wordt openlijk beschreven. Johans emancipatiestrijd was verbonden met de strijd tegen het antisemitisme. Hij schreef: ‘Er is in homosexuelen een hypersensitiviteit voor taal en schoonheid aanwezig, juist nu. De kans bestaat dat zij instinctief reeds voelen, zoals de Joden voorheen, dat zij getekend zijn en reeds op het punt staan als verworpenen te worden uitgeroeid. Ik ben op dat punt pessimistisch en zie allerlei onrustbarende tekenen.’

J.B.W.P. – De biografie van uitgever Johan Polak

Koen Hilberdink is literatuurwetenschapper en werkzaam bij de Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen. Hij promoveerde op Ik ben een vreemdeling. Ik sta apart. Een biografie van Paul Rodenko (2000). In 2007 verscheen zijn biografie over dichter Hans Lodeizen.

Koen Hilberdink

J.B.W.P.

Het leven van Johan Polak

Uitgeverij Van Oorschot, Amsterdam

Juni 2017, gebonden, € 29,99

ISBN 9789028261846

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, Johan Polak, LGBT+ (lhbt+), PRESS & PUBLISHING, Racism, The Art of Reading

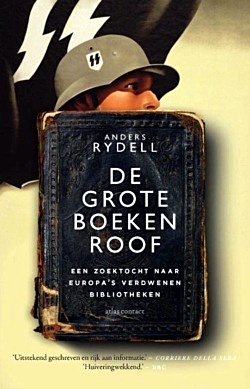

Op 10 mei 1933 staken nazi’s op de Opernplatz in Berlijn, onder toeziend oog van 40.000 toeschouwers, zo’n 25.000 boeken in de fik.

Op 10 mei 1933 staken nazi’s op de Opernplatz in Berlijn, onder toeziend oog van 40.000 toeschouwers, zo’n 25.000 boeken in de fik.

Het was het startsein voor een reeks boekverbrandingen overal in Duitsland.

Over die gebeurtenis is veel geschreven, maar onbekend is het veel sinisterder plan dat de nazi’s in heel Europa ten uitvoer brachten: het plunderen van bibliotheken en privébezit, met als doel de literatuur in te zetten als wapen in de vernietigingsmachinerie.

Tegenstanders werden zo niet alleen van hun vrijheid beroofd maar ook van hun literatuur, hun verhalen, hun emotionele en intellectuele geschiedenis.

In De grote boekenroof volgt Anders Rydell het spoor van de boekenplunderaars door Europa. Hij reist onder meer naar Den Haag en Amsterdam, struint door de bibliotheken van Berlijn en Parijs en gaat op zoek naar de mysterieus verdwenen Joodse bibliotheek in Rome.

Zo vertelt Rydell het verhaal van een van de meest angstaanjagende nazi-ambities op het gebied van kunst, cultuur en onderwijs.

Anders Rydell

De grote boekenroof

Vertaling door Robert Starke

Afm. 26x210x135 mm

Verschijningsdatum:

april 2017

Paperback = 27,99

ISBN10 9045031914

ISBN13 9789045031910

Atlas Contact, Uitgeverij

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, The Art of Reading

Pulitzer Prizes

Pulitzer Prizes

Pulitzer Prize administrator Mike Pride has announced today (april 10) the winners of the 2017 Pulitzer Prizes in the World Room at Columbia University in New York, N.Y.

This announcement marks the 101st year of the prizes. The Pulitzer Prizes have been awarded by Columbia University each spring since 1917.

The awards are chosen by a board of jurors for Journalism, Letters, Music and Drama.

The 2017 Winners in Letters, Drama and Music:

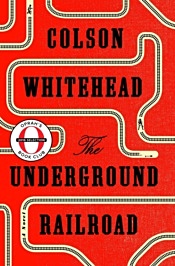

Fiction

The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead

From prize-winning, bestselling author Colson Whitehead, a magnificent tour de force chronicling a young slave’s adventures as she makes a desperate bid for freedom in the antebellum South.

Poetry

Poetry

Olio by Tyehimba Jess

Part fact, part fiction, Tyehimba Jess’s much anticipated second book weaves sonnet, song, and narrative to examine the lives of mostly unrecorded African American performers, musicians and artists directly before and after the Civil War up to World War I. Olio is an effort to understand how they met, resisted, complicated, co-opted, and sometimes defeated attempts to minstrelize them.

History

Blood in the Water: The Atica Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy by Heather Ann Thompson

On September 9, 1971, nearly 1,300 prisoners took over the Attica Correctional Facility in upstate New York to protest years of mistreatment. Drawing from more than a decade of extensive research, historian Heather Ann Thompson sheds new light on every aspect of the uprising and its legacy, giving voice to all those who took part in this forty-five-year fight for justice.

Nonfiction

Nonfiction

Evicted by Matthew Desmond

Staff Pick: In this brilliant, heartbreaking book, Matthew Desmond takes us into the poorest neighborhoods of Milwaukee to tell the story of eight families on the edge.

Biography or Autobiography

The Return: Fathers, Sons and the Land in Between by Hisham Matar

The Return is at once an exquisite meditation on history, politics, and art, a brilliant portrait of a nation and a people on the cusp of change, and a disquieting depiction of the brutal legacy of absolute power. Above all, it is a universal tale of loss and love and of one family’s life.

List of all this years Pulitzer Prize winners:

Journalism

Public Service: The staff of the New York Daily News and ProPublica.

Breaking News Reporting: The staff of East Bay Times.

Investigative Reporting: Eric Eyre, the Charleston Gazette-Mail.

Explanatory Reporting: The Panama Papers, by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, McClatchy and the Miami Herald.

Local Reporting: The staff of The Salt Lake Tribune.

National Reporting: David Fahrenthold, The Washington Post.

International Reporting: The staff of The New York Times.

Feature Writing: C.J. Chivers of The New York Times.

Commentary: Peggy Noonan, The Wall Street Journal.

Criticism: Hilton Als, The New Yorker.

Editorial Writing: Art Cullen, The Storm Lake Times.

Editorial Cartooning: Jim Morin, Miami Herald.

Breaking News Photography: Daniel Berehulak, The New York Times.

Feature Photography: E. Jason Wambsgans, Chicago Tribune.

Letters, Drama, & Music

Fiction: The Underground Railroad, by Colson Whitehead.

Drama: Sweat, by Lynn Nottage.

History: Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy, by Heather Ann Thompson.

Biography or Autobiography: The Return, by Hisham Matar.

Poetry: Olio, by Tyehimba Jess.

General Nonfiction: Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, by Matthew Desmond.

Music: Angel’s Bone, by Du Yun.

# more information on website pulitzer

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Awards & Prizes, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Illustrators, Illustration, MONTAIGNE, MUSIC, Photography, PRESS & PUBLISHING, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS, The Art of Reading, THEATRE

Het bestuur van de Stichting P.C. Hooft-prijs voor Letterkunde heeft maandag 12 december besloten de P.C. Hooft-prijs 2017 toe te kennen aan Bas Heijne (Nijmegen, 1960).

Het bestuur van de Stichting P.C. Hooft-prijs voor Letterkunde heeft maandag 12 december besloten de P.C. Hooft-prijs 2017 toe te kennen aan Bas Heijne (Nijmegen, 1960).

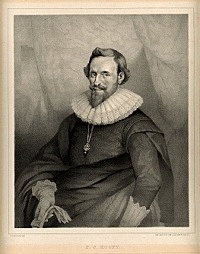

Deze oeuvreprijs is dit jaar bestemd voor beschouwend proza en wordt uitgereikt op een feestelijke bijeenkomst in het Literatuurmuseum, op donderdag 18 mei 2017, 3 dagen vóór de sterfdag van de naamgever van de prijs, de dichter P.C. Hooft (1581-1647), onze grootste renaissancedichter.

De P.C. Hooft-prijs 2017 voor het gehele oeuvre van Bas Heijne is toegekend op voordracht van een jury bestaande uit Jacqueline Bel, Kees ’t Hart, Kristien Hemmerechts, David Van Reybrouck (voorzitter) en Dirk van Weelden. Recente eerdere laureaten in het genre beschouwend proza waren Willem Jan Otten (2014), H.J.A. Hofland (2011) en Abram de Swaan (2008). Aan de prijs is een bedrag verbonden van € 60.000.

Uit het juryrapport: “Bas Heijne is een schrijver met een bijzondere positie als columnist en essayist, die over een enorme verscheidenheid aan actuele onderwerpen en kwesties schrijft. Hij volgt de hedendaagse cultuur op een geëngageerde manier. Hij schrijft over haatvloggers en De Ring van Wagner, over Hollywoodfilms en Couperus, over Europese referenda en de toekomst van de roman. Zijn werk geeft een vernieuwende impuls aan wat literatuur in maatschappelijke zin betekenen kan. […] Vooral de vorm waarin hij dat doet is bijzonder: hij schrijft als een denker én denkt als een lezer.”

Uit het juryrapport: “Bas Heijne is een schrijver met een bijzondere positie als columnist en essayist, die over een enorme verscheidenheid aan actuele onderwerpen en kwesties schrijft. Hij volgt de hedendaagse cultuur op een geëngageerde manier. Hij schrijft over haatvloggers en De Ring van Wagner, over Hollywoodfilms en Couperus, over Europese referenda en de toekomst van de roman. Zijn werk geeft een vernieuwende impuls aan wat literatuur in maatschappelijke zin betekenen kan. […] Vooral de vorm waarin hij dat doet is bijzonder: hij schrijft als een denker én denkt als een lezer.”

De P.C. Hooft-prijs voor Letterkunde behoort tot de belangrijke literatuurprijzen in het Nederlandse taalgebied. Hij wordt uitgereikt door de Stichting P.C. Hooft-prijs voor Letterkunde. Deze oeuvreprijs wordt jaarlijks afwisselend toegekend voor proza, essayistiek en poëzie. De P.C. Hooft-prijs is ingesteld in 1947. In dat jaar werd op 21 mei de 300ste sterfdag van Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft herdacht. De prijs wordt jaarlijks rond de sterfdag van P.C. Hooft uitgereikt en bedraagt € 60.000. Daarnaast looft de Stichting sinds 1988 de driejaarlijkse Theo Thijssen-prijs uit voor jeugdliteratuur. De prijs bedraagt € 60.000.

Vanaf september 2007 wordt de driejaarlijkse Max Velthuijs-prijs voor boekillustratoren uitgereikt. Ook deze prijs bedraagt € 60.000.’

# Meer informatie op website PC Hooftprijs

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Bas Heijne, NONFICTION: ESSAYS & STORIES, PRESS & PUBLISHING, The Art of Reading

Le bookfighting est un sport de combat : deux adversaires (protégés), s’affrontent avec des livres (de poche!), sous le contrôle d’un arbitre. Chaque touche vaut un point dans une partie en sept jeux. Point fort du règlement : la possibilité à tout moment d’ouvrir un livre, sa lecture, pour soi ou à voix haute, ayant pour effet immédiat d’interrompre le combat. La véhémence initiale cède ainsi à l’autorité du livre, le combat-lecture instaurant un indécidable aller-retour entre deux états connus et opposés, nature et culture. Au terme du combat, l’arbitre annonce le résultat et désigne le vainqueur sous les applaudissements du public, convié à participer s’il le désire.

Le bookfighting est un sport de combat : deux adversaires (protégés), s’affrontent avec des livres (de poche!), sous le contrôle d’un arbitre. Chaque touche vaut un point dans une partie en sept jeux. Point fort du règlement : la possibilité à tout moment d’ouvrir un livre, sa lecture, pour soi ou à voix haute, ayant pour effet immédiat d’interrompre le combat. La véhémence initiale cède ainsi à l’autorité du livre, le combat-lecture instaurant un indécidable aller-retour entre deux états connus et opposés, nature et culture. Au terme du combat, l’arbitre annonce le résultat et désigne le vainqueur sous les applaudissements du public, convié à participer s’il le désire.

Bookfighting Performance Yves Duranthon

Date: 07/05/2015 – 18:00

MUSEE PALAIS DE TOKYO

13, avenue du Président Wilson,

75 116 Paris

Bookfighting: Men, women, and children fighting with books. The show is captivating and you can not manage to turn a blind eye to these objects being handled in such a manner. Is this the way to treat culture and the great minds of our civilization? It’s outrageous and you want to react, but you keep it inside, because you don’t know how to release your anger.

Bookfighting: Men, women, and children fighting with books. The show is captivating and you can not manage to turn a blind eye to these objects being handled in such a manner. Is this the way to treat culture and the great minds of our civilization? It’s outrageous and you want to react, but you keep it inside, because you don’t know how to release your anger.

The show goes on, regardless of your uneasiness and good judgment, and eventually you succumb to the spectacle. You are fascinated by the disturbing yet beautiful event of fighters energetically chucking books at each other.

You come back later, armed with books taken from your own library, and get involved in the fighting yourself so that you can discover the flip side of culture.

# Website Palais de Tokyo

Bookfighting Performance Yves Duranthon

# Website Yves Duranthon bookfighting performance

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Art & Literature News, Exhibition Archive, Libraries in Literature, Performing arts, The Art of Reading, THEATRE

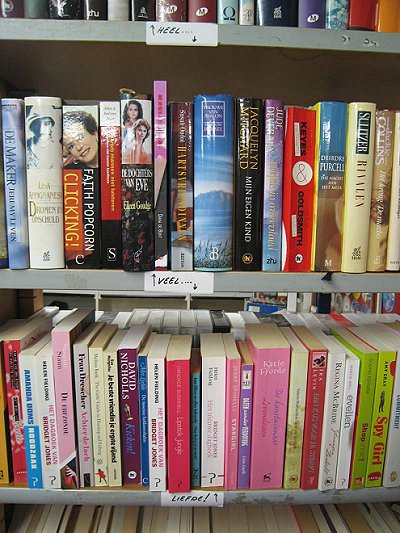

Joep Eijkens

Heel veel liefde

Ik zie:

Dromen van onschuld

Waarom mannen niet luisteren

De Dochters van Eve

Hartsvriendinnen

Liefde in overvloed

Die Nacht aan het Meer

De Erfzonde

Je beste vriendin je ergste vijand

De mooiste liefdesverhalen

Een kus voor je sterft

Daten zonder verdoving

Hoe dump je je vent

Kortom:

heel….

veel….

liefde!

(bij de afdeling tweedehandsboeken in Kringloopcentrum Altena te Almerk).

Foto en tekst Joep Eijkens

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Bookstores, Joep Eijkens Photos, The Art of Reading

Stichting Cools doet boekje open over leesclubs

‘Vrouwen kunnen beter lezen!’

TILBURG – Stichting dr. P.J. Cools msc brengt traditiegetrouw een boekje over lezen en boeken uit bij gelegenheid van ‘Boeken rond het Paleis’, de grootste tweedehandsboekenmarkt van Zuid-Nederland. Ging het boekje vorig jaar over foto’s van lezende mensen vroeger en nu, dit jaar staan leesclubs in de schijnwerper. ‘De Lekkere Letters en andere leesclubs’, luidt de titel van het door Joep Eijkens en Norbert de Vries samengestelde boekje.

Alleen al Midden-Brabant telt tientallen leesclubs. Voor de buitenwereld zijn ze niet erg zichtbaar. Begrijpelijk, want veelal komen de leden thuis bij elkaar. Ze vormen hechte groepen waarin het draait om lezen en vriendschap. En alleen al daarom vormen leesclubs een interessant sociaal en cultureel fenomeen.

Eijkens en De Vries hebben 27 leesclubs uit Midden-Brabant te boek gesteld. “Ik denk, dat we via dit boekje een goede indruk hebben kunnen geven van het functioneren van een leesclub”, zegt De Vries. “Beschouw ons boekje maar als een hommage aan al die groepen.”

Inleven

Opvallend is, dat de meeste leesclubs uitsluitend uit vrouwen bestaan. Leesclubleden zelf hebben daar, desgevraagd, wel verschillende verklaringen voor. Uit hun antwoorden komt naar voren, dat vrouwen zich graag verplaatsen in de wereld van anderen, en daarover graag praten. Een van de vrouwen formuleerde het als volgt:“Vrouwen kunnen beter lezen! Althans, waar het literatuur betreft. Bij een roman moet je je betrokken voelen, moet je je inleven in de personages en omstandigheden. Nou, vrouwen kunnen dat beter dan mannen. Ze zijn nieuwsgierig naar mensen, naar hoe en waarom ze hun leven leiden, zoals ze het leiden (kortom: naar de geschiedenis). Daarnaast willen vrouwen graag hun ideeën, gedachten, ervaringen en gevoelens hierover met elkaar delen. Mannen lezen meer ‘doelgericht’, om kennis te vergaren, nuttige kennis waar ze direct voordeel van hebben. Over literatuur praten is voor mannen vaak small talk bij de borrel. Dat is ietwat gechargeerd, maar in de kern komt het hier wel op neer.”

De Lekkere Letters

‘De Lekkere Letters’ is de naam van één van de 27 Midden-Brabantse leesclubs die in het boekje opgenomen zijn. Veel leesclubs hebben daarentegen geen naam. Alle 27 passeren de revue in woord en beeld, waarbij Joep Eijkens voor de fotografie zorgde.

Uit de 27 portretten valt op te maken, dat het imago van ‘theekransjes’, dat de leesclubs aankleeft, geheel onterecht is. Weliswaar zie je op de foto’s hoe de leden gewoonlijk bijeen zitten aan een tafel, en dat op die tafel niet enkel boeken zichtbaar zijn, maar meestal ook kopjes, een schaaltje met wat lekkernijen, en een koffie- of theepot, maar uit de beschrijvingen blijkt zonneklaar, dat bij de besprekingen de ernst de boventoon voert.

De leden bereiden zich ook serieus voor. Zij lezen het boek, en sommigen bestuderen het: men verzamelt achtergrondinformatie over de auteur, men verdiept zich in de historische situatie die in het boek aan de orde komt, en men slaat er recensies van het boek op na. Ook de boekbespreking zelf gebeurt veelal op een zeer gedegen wijze. Soms komen daarbij plattegrondtekeningen op tafel waarop het verloop van de gebeurtenissen en de rol daarin van de hoofdfiguren in beeld is gebracht. Ook komt het voor dat men tijdens de bijeenkomst naar de muziek luistert die in het boek wordt genoemd.

Géén ‘small talk’

‘Dit alles staat ver af van small talk en theekransjes’, aldus Norbert de Vries, tevens voorzitter van de stichting die het boekje uitgeeft. ‘Naast gedegenheid is er genegenheid, ofwel het sociale aspect van de leesclubs. Vriendschap en plezier enerzijds, en belangstelling voor literatuur anderzijds: die beide elementen vormen de kern van de leesclub’.

Sommige leesclubs komen voort uit een vriendinnengroep, andere wórden een vriendinnengroep. De onderlinge band is vaak zeer sterk. Dit leidt er toe, dat veel clubs ook activiteiten op een ‘aanpalend’ terrein gaan ontwikkelen: het gezamenlijk bezoek aan tentoonstelling, film of toneel, of het organiseren van een eigen weekend met daarin culturele/literaire excursies.

‘De Lekkere Letters en andere leesclubs’ . Tekst Joep Eijkens en Norbert de Vries. Fotografie Joep Eijkens. Het boekje is op de boekenmarkt ‘Boeken rond het Paleis’ op 26 augustus 2012 voor 7,50 euro te koop bij de kraam van de Stichting dr P.J. Cools msc.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, The Art of Reading

More in: The Art of Reading, The talk of the town

Virginia Woolf

How Should One Read a Book?

In the first place, I want to emphasize the note of interrogation at the end of my title. Even if I could answer the question for myself, the answer would apply only to me and not to you. The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. If this is agreed between us, then I feel at liberty to put forward a few ideas and suggestions because you will not allow them to fetter that independence which is the most important quality that a reader can possess. After all, what laws can be laid down about books? The battle of Waterloo was certainly fought on a certain day; but is Hamlet a better play than Lear? Nobody can say. Each must decide that question for himself. To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions—there we have none.

But to enjoy freedom, if the platitude is pardonable, we have of course to control ourselves. We must not squander our powers, helplessly and ignorantly, squirting half the house in order to water a single rose-bush; we must train them, exactly and powerfully, here on the very spot. This, it may be, is one of the first difficulties that faces us in a library. What is “the very spot?” There may well seem to be nothing but a conglomeration and huddle of confusion. Poems and novels, histories and memories, dictionaries and blue-books; books written in all languages by men and women of all tempers, races, and ages jostle each other on the shelf. And outside the donkey brays, the women gossip at the pump, the colts gallop across the fields. Where are we to begin? How are we to bring order into this multitudinous chaos and so get the deepest and widest pleasure from what we read?

It is simple enough to say that since books have classes—fiction, biography, poetry—we should separate them and take from each what it is right that each should give us. Yet few people ask from books what books can give us. Most commonly we come to books with blurred and divided minds, asking of fiction that it shall be true, of poetry that it shall be false, of biography that it shall be flattering, of history that it shall enforce our own prejudices. If we could banish all such preconceptions when we read, that would be an admirable beginning. Do not dictate to your author; try to become him. Be his fellow-worker and accomplice. If you hang back, and reserve and criticize at first, you are preventing yourself from getting the fullest possible value from what you read. But if you open your mind as widely as possible, then signs and hints of almost imperceptible fineness, from the twist and turn of the first sentences, will bring you into the presence of a human being unlike any other. Steep yourself in this, acquaint yourself with this, and soon you will find that your author is giving you, or attempting to give you, something far more definite. The thirty-chapters of a novel—if we consider how to read a novel first—are an attempt to make something as formed and controlled as a building: but words are more impalpable than bricks; reading is a longer and more complicated process than seeing. Perhaps the quickest way to understand the elements of what a novelist is doing is not to read, but to write; to make your own experiment with the dangers and difficulties of words. Recall, then, some event that has left a distinct impression on you— how at the corner of the street, perhaps, you passed two people talking. A tree shook; an electric light danced; the tone of the talk was comic, but also tragic; a whole vision, an entire conception, seemed contained in that moment.

But when you attempt to reconstruct it in words, you will find that it breaks into a thousand conflicting impressions. Some must be subdued; others emphasized; in the process you will lose, probably, all grasp upon the emotion itself. Then turn from your blurred and littered pages to the opening pages of some great novelist—Defoe, Jane Austen, Hardy. Now you will be better able to appreciate their mastery. It is not merely that we are in the presence of a different person—Defoe, Jane Austen, or Thomas Hardy—but that we are living in a different world. Here, in Robinson Crusoe, we are trudging a plain high road; one thing happens after another; the fact and the order of the fact is enough. But if the open air and adventure mean everything to Defoe they mean nothing to Jane Austen. Hers is the drawing-room, and people talking, and by the many mirrors of their talk revealing their characters. And if, when we have accustomed ourselves to the drawing-room and its reflections, we turn to Hardy, we are once more spun round. The moors are round us and the stars are above our heads. The other side of the mind is now exposed—the dark side that comes uppermost in solitude, not the light side that shows in company. Our relations are not towards people, but towards Nature and destiny. Yet different as these worlds are, each is consistent with itself. The maker of each is careful to observe the laws of his own perspective, and however great a strain they may put upon us they will never confuse us, as lesser writers so frequently do, by introducing two different kinds of reality into the same book. Thus to go from one great novelist to another—from Jane Austen to Hardy, from Peacock to Trollope, from Scott to Meredith—is to be wrenched and uprooted; to be thrown this way and then that. To read a novel is a difficult and complex art. You must be capable not only of great fineness of perception, but of great boldness of imagination if you are going to make use of all that the novelist—the great artist—gives you.

But a glance at the heterogeneous company on the shelf will show you that writers are very seldom “great artists;” far more often a book makes no claim to be a work of art at all. These biographies and autobiographies, for example, lives of great men, of men long dead and forgotten, that stand cheek by jowl with the novels and poems, are we to refuse to read them because they are not “art?” Or shall we read them, but read them in a different way, with a different aim? Shall we read them in the first place to satisfy that curiosity which possesses us sometimes when in the evening we linger in front of a house where the lights are lit and the blinds not yet drawn, and each floor of the house shows us a different section of human life in being? Then we are consumed with curiosity about the lives of these people—the servants gossiping, the gentlemen dining, the girl dressing for a party, the old woman at the window with her knitting. Who are they, what are they, what are their names, their occupations, their thoughts, and adventures?

Biographies and memoirs answer such questions, light up innumerable such houses; they show us people going about their daily affairs, toiling, failing, succeeding, eating, hating, loving, until they die. And sometimes as we watch, the house fades and the iron railings vanish and we are out at sea; we are hunting, sailing, fighting; we are among savages and soldiers; we are taking part in great campaigns. Or if we like to stay here in England, in London, still the scene changes; the street narrows; the house becomes small, cramped, diamond-paned, and malodorous. We see a poet, Donne, driven from such a house because the walls were so thin that when the children cried their voices cut through them. We can follow him, through the paths that lie in the pages of books, to Twickenham; to Lady Bedford’s Park, a famous meeting-ground for nobles and poets; and then turn our steps to Wilton, the great house under the downs, and hear Sidney read the Arcadia to his sister; and ramble among the very marshes and see the very herons that figure in that famous romance; and then again travel north with that other Lady Pembroke, Anne Clifford, to her wild moors, or plunge into the city and control our merriment at the sight of Gabriel Harvey in his black velvet suit arguing about poetry with Spenser. Nothing is more fascinating than to grope and stumble in the alternate darkness and splendor of Elizabethan London. But there is no staying there. The Temples and the Swifts, the Harleys and the St Johns beckon us on; hour upon hour can be spent disentangling their quarrels and deciphering their characters; and when we tire of them we can stroll on, past a lady in black wearing diamonds, to Samuel Johnson and Goldsmith and Garrick; or cross the channel, if we like, and meet Voltaire and Diderot, Madame du Deffand; and so back to England and Twickenham—how certain places repeat themselves and certain names!—where Lady Bedford had her Park once and Pope lived later, to Walpole’s home at Strawberry Hill. But Walpole introduces us to such a swarm of new acquaintances, there are so many houses to visit and bells to ring that we may well hesitate for a moment, on the Miss Berrys’ doorstep, for example, when behold, up comes Thackeray; he is the friend of the woman whom Walpole loved; so that merely by going from friend to friend, from garden to garden, from house to house, we have passed from one end of English literature to another and wake to find ourselves here again in the present, if we can so differentiate this moment from all that have gone before. This, then, is one of the ways in which we can read these lives and letters; we can make them light up the many windows of the past; we can watch the famous dead in their familiar habits and fancy sometimes that we are very close and can surprise their secrets, and sometimes we may pull out a play or a poem that they have written and see whether it reads differently in the presence of the author. But this again rouses other questions. How far, we must ask ourselves, is a book influenced by its writer’s life—how far is it safe to let the man interpret the writer? How far shall we resist or give way to the sympathies and antipathies that the man himself rouses in us—so sensitive are words, so receptive of the character of the author? These are questions that press upon us when we read lives and letters, and we must answer them for ourselves, for nothing can be more fatal than to be guided by the preferences of others in a matter so personal.

But also we can read such books with another aim, not to throw light on literature, not to become familiar with famous people, but to refresh and exercise our own creative powers. Is there not an open window on the right hand of the bookcase? How delightful to stop reading and look out! How stimulating the scene is, in its unconsciousness, its irrelevance, its perpetual movement—the colts galloping round the field, the woman filling her pail at the well, the donkey throwing back his head and emitting his long, acrid moan. The greater part of any library is nothing but the record of such fleeting moments in the lives of men, women, and donkeys. Every literature, as it grows old, has its rubbish-heap, its record of vanished moments and forgotten lives told in faltering and feeble accents that have perished. But if you give yourself up to the delight of rubbish-reading you will be surprised, indeed you will be overcome, by the relics of human life that have been cast out to molder. It may be one letter—but what a vision it gives! It may be a few sentences—but what vistas they suggest! Sometimes a whole story will come together with such beautiful humor and pathos and completeness that it seems as if a great novelist had been at work, yet it is only an old actor, Tate Wilkinson, remembering the strange story of Captain Jones; it is only a young subaltern serving under Arthur Wellesley and falling in love with a pretty girl at Lisbon; it is only Maria Allen letting fall her sewing in the empty drawing-room and sighing how she wishes she had taken Dr Burney’s good advice and had never eloped with her Rishy. None of this has any value; it is negligible in the extreme; yet how absorbing it is now and again to go through the rubbish-heaps and find rings and scissors and broken noses buried in the huge past and try to piece them together while the colt gallops round the field, the woman fills her pail at the well, and the donkey brays.

But we tire of rubbish-reading in the long run. We tire of searching for what is needed to complete the half-truth which is all that the Wilkinsons, the Bunburys and the Maria Allens are able to offer us. They had not the artist’s power of mastering and eliminating; they could not tell the whole truth even about their own lives; they have disfigured the story that might have been so shapely. Facts are all that they can offer us, and facts are a very inferior form of fiction. Thus the desire grows upon us to have done with half-statements and approximations; to cease from searching out the minute shades of human character, to enjoy the greater abstractness, the purer truth of fiction. Thus we create the mood, intense and generalized, unaware of detail, but stressed by some regular, recurrent beat, whose natural expression is poetry; and that is the time to read poetry when we are almost able to write it.

Western wind, when wilt thou blow?

The small rain down can rain.

Christ, if my love were in my arms,

And I in my bed again!

The impact of poetry is so hard and direct that for the moment there is no other sensation except that of the poem itself. What profound depths we visit then—how sudden and complete is our immersion! There is nothing here to catch hold of; nothing to stay us in our flight. The illusion of fiction is gradual; its effects are prepared; but who when they read these four lines stops to ask who wrote them, or conjures up the thought of Donne’s house or Sidney’s secretary; or enmeshes them in the intricacy of the past and the succession of generations? The poet is always our contemporary. Our being for the moment is centered and constricted, as in any violent shock of personal emotion. Afterwards, it is true, the sensation begins to spread in wider rings through our minds; remoter senses are reached; these begin to sound and to comment and we are aware of echoes and reflections. The intensity of poetry covers an immense range of emotion. We have only to compare the force and directness of

I shall fall like a tree, and find my grave,

Only remembering that I grieve,

with the wavering modulation of

Minutes are numbered by the fall of sands,

As by an hour glass; the span of time

Doth waste us to our graves, and we look on it;

An age of pleasure, revelled out, comes home

At last, and ends in sorrow; but the life,

Weary of riot, numbers every sand,

Wailing in sighs, until the last drop down,

So to conclude calamity in rest

or place the meditative calm of

whether we be young or old,

Our destiny, our being’s heart and home,

Is with infinitude, and only there;

With hope it is, hope that can never die,

Effort, and expectation, and desire,

And effort evermore about to be,

beside the complete and inexhaustible loveliness of

The moving Moon went up the sky,

And nowhere did abide:

Softly she was going up,

And a star or two beside—

or the splendid fantasy of

And the woodland haunter

Shall not cease to saunter

When, far down some glade,

Of the great world’s burning,

One soft flame upturning

Seems to his discerning,

Crocus in the shade,

to bethink us of the varied art of the poet; his power to make us at once actors and spectators; his power to run his hand into characters as if it were a glove, and be Falstaff or Lear; his power to condense, to widen, to state, once and for ever.

“We have only to compare”—with those words the cat is out of the bag, and the true complexity of reading is admitted. The first process, to receive impressions with the utmost understanding, is only half the process of reading; it must be completed, if we are to get the whole pleasure from a book, by another. We must pass judgment upon these multitudinous impressions; we must make of these fleeting shapes one that is hard and lasting. But not directly. Wait for the dust of reading to settle; for the conflict and the questioning to die down; walk, talk, pull the dead petals from a rose, or fall asleep. Then suddenly without our willing it, for it is thus that Nature undertakes these transitions, the book will return, but differently. It will float to the top of the mind as a whole. And the book as a whole is different from the book received currently in separate phrases. Details now fit themselves into their places. We see the shape from start to finish; it is a barn, a pig-sty, or a cathedral. Now then we can compare book with book as we compare building with building. But this act of comparison means that our attitude has changed; we are no longer the friends of the writer, but his judges; and just as we cannot be too sympathetic as friends, so as judges we cannot be too severe. Are they not criminals, books that have wasted our time and sympathy; are they not the most insidious enemies of society, corrupters, defilers, the writers of false books, faked books, books that fill the air with decay and disease? Let us then be severe in our judgments; let us compare each book with the greatest of its kind. There they hang in the mind the shapes of the books we have read solidified by the judgments we have passed on them—Robinson Crusoe, Emma The Return of the Native. Compare the novels with these—even the latest and least of novels has a right to be judged with the best. And so with poetry when the intoxication of rhythm has died down and the splendor of words has faded, a visionary shape will return to us and this must be compared with Lear, with Phèdre, with The Prelude; or if not with these, with whatever is the best or seems to us to be the best in its own kind. And we may be sure that the newness of new poetry and fiction is its most superficial quality and that we have only to alter slightly, not to recast, the standards by which we have judged the old.

It would be foolish, then, to pretend that the second part of reading, to judge, to compare, is as simple as the first—to open the mind wide to the fast flocking of innumerable impressions. To continue reading without the book before you, to hold one shadow-shape against another, to have read widely enough and with enough understanding to make such comparisons alive and illuminating—that is difficult; it is still more difficult to press further and to say, “Not only is the book of this sort, but it is of this value; here it fails; here it succeeds; this is bad; that is good.” To carry out this part of a reader’s duty needs such imagination, insight, and learning that it is hard to conceive any one mind sufficiently endowed; impossible for the most self-confident to find more than the seeds of such powers in himself. Would it not be wiser, then, to remit this part of reading and to allow the critics, the gowned and furred authorities of the library, to decide the question of the book’s absolute value for us? Yet how impossible! We may stress the value of sympathy; we may try to sink our own identity as we read. But we know that we cannot sympathize wholly or immerse ourselves wholly; there is always a demon in us who whispers, “I hate, I love,” and we cannot silence him. Indeed, it is precisely because we hate and we love that our relation with the poets and novelists is so intimate that we find the presence of another person intolerable. And even if the results are abhorrent and our judgments are wrong, still our taste, the nerve of sensation that sends shocks through us, is our chief illuminant; we learn through feeling; we cannot suppress our own idiosyncrasy without impoverishing it. But as time goes on perhaps we can train our taste; perhaps we can make it submit to some control. When it has fed greedily and lavishly upon books of all sorts—poetry, fiction, history, biography—and has stopped reading and looked for long spaces upon the variety, the incongruity of the living world, we shall find that it is changing a little; it is not so greedy, it is more reflective. It will begin to bring us not merely judgments on particular books, but it will tell us that there is a quality common to certain books. Listen, it will say, what shall we call this? And it will read us perhaps Lear and then perhaps the Agamemnon in order to bring out that common quality. Thus, with our taste to guide us, we shall venture beyond the particular book in search of qualities that group books together; we shall give them names and thus frame a rule that brings order into our perceptions. We shall gain a further and a rarer pleasure from that discrimination. But as a rule only lives when it is perpetually broken by contact with the books themselves—nothing is easier and more stultifying than to make rules which exists out of touch with facts, in a vacuum—now at last, in order to steady ourselves in this difficult attempt, it may be well to turn to the very rare writers who are able to enlighten us upon literature as an art. Coleridge and Dryden and Johnson, in their considered criticism, the poets and novelists themselves in their unconsidered sayings, are often surprisingly relevant; they light up and solidify the vague ideas that have been tumbling in the misty depths of our minds. But they are only able to help us if we come to them laden with questions and suggestions won honestly in the course of our own reading. They can do nothing for us if we herd ourselves under their authority and lie down like sheep in the shade of a hedge. We can only understand their ruling when it comes in conflict with our own and vanquishes it.

If this is so, if to read a book as it should be read calls for the rarest qualities of imagination, insight, and judgment, and you may perhaps conclude that literature is a very complex art and that it is unlikely that we shall be able, even after a lifetime of reading, to make any valuable contribution to its criticism. We must remain readers; we shall not put on the further glory that belongs to those rare beings who are also critics. But still we have our responsibilities as readers and even our importance. The standards we raise and the judgments we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work. An influence is created which tells upon them even if it never finds its way into print. And that influence, if it were well instructed, vigorous and individual and sincere, might be of great value now when criticism is necessarily in abeyance; when books pass in review like the procession of animals in a shooting gallery, and the critic has only one second in which to load and aim and shoot and may well be pardoned if he mistakes rabbits for tigers, eagles for barndoor fowls, or misses altogether and wastes his shot upon some peaceful cow grazing in a further field. If behind the erratic gunfire of the press the author felt that there was another kind of criticism, the opinion of people reading for the love of reading, slowly and unprofessionally, and judging with great sympathy and yet with great severity, might this not improve the quality of his work? And if by our means books were to become stronger, richer, and more varied, that would be an end worth reaching.

Yet who reads to bring about an end, however desirable? Are there not some pursuits that we practice because they are good in themselves, and some pleasures that are final? And is not this among them? I have sometimes dreamt, at least that when the Day of judgment dawns and the great conquerors and lawyers and statesmen come to receive their rewards—their crowns, their laurels, their names carved indelibly upon imperishable marble—the Almighty will turn to Peter and will say, not without a certain envy when He sees us coming with our books under our arms, “Look, these need no reward. We have nothing to give them here. They have loved reading.”

Virgina Woolf

(The Common Reader, Second Series 1926)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Libraries in Literature, The Art of Reading, Woolf, Virginia

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature