Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

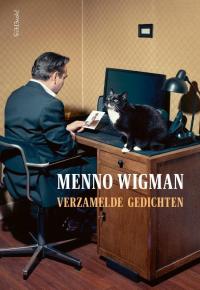

M enno Wigman (1966-2018) was een van de grootste en eigenzinnigste dichters van Nederland.

enno Wigman (1966-2018) was een van de grootste en eigenzinnigste dichters van Nederland.

Zijn stijl werd gekenmerkt door een zwart-romantische toon die, afgewisseld met een weemoedige blik, direct tot de verbeelding sprak. Zijn gedichten waren even toegankelijk als experimenteel, een combinatie van een uitgesproken intensiteit met de beleving van het alledaagse. Wigmans Verzamelde gedichten zijn samengesteld door Neeltje Maria Min en Rob Schouten, zijn goede vrienden en de beste kenners van zijn werk.

Van Menno Wigman (1966-2018) verschenen vijf dichtbundels, een dagboek, een essaybundel en vele vertalingen, bloemlezingen en gelegenheidsuitgaven. Tot de vele prijzen die hij kreeg, behoren de Gedichtendagprijs (2002), de Jan Campert-prijs (2002), de A. Roland Holstprijs (2015) en de Ida Gerhardt Poëzieprijs (2018).

Verzamelde gedichten

Menno Wigman

336 pagina’s

Druk 1

Verschenen 27-09-19

Taal Nederlands

Poëzie

Gebonden

ISBN 9789044641936

Uitgever Prometheus

€ 29,99

# new poetry

menno wigman

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Wigman, Menno

O Blik vol Dood en Sterren

o Blik vol dood en sterren,

o hart vol licht en leed.

De dag is spijtig verre;

de nacht is hel en wreed.

Mijn mond vol wondre smaken

die géne vrucht verzaadt.

Niemand, o hunkrend waken,

die langs mijn venster gaat…

Wij zullen nimmer wezen

dan Godes angst’ge wezen.

– God, laat ons waan en schijn

dat we Uwe wezen zijn.

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

O Blik vol Dood en Sterren

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

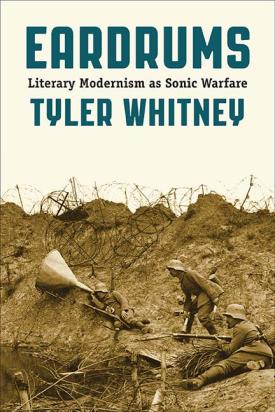

In this innovative study, Tyler Whitney demonstrates how a transformation and militarization of the civilian soundscape in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries left indelible traces on the literature that defined the period.

Both formally and thematically, the modernist aesthetics of Franz Kafka, Robert Musil, Detlev von Liliencron, and Peter Altenberg drew on this blurring of martial and civilian soundscapes in traumatic and performative repetitions of war.

Both formally and thematically, the modernist aesthetics of Franz Kafka, Robert Musil, Detlev von Liliencron, and Peter Altenberg drew on this blurring of martial and civilian soundscapes in traumatic and performative repetitions of war.

At the same time, Richard Huelsenbeck assaulted audiences in Zurich with his “sound poems,” which combined references to World War I, colonialism, and violent encounters in urban spaces with nonsensical utterances and linguistic detritus—all accompanied by the relentless beating of a drum on the stage of the Cabaret Voltaire.

Eardrums is the first book-length study to explore the relationship between acoustical modernity and German modernism, charting a literary and cultural history written in and around the eardrum. The result is not only a new way of understanding the sonic impulses behind key literary texts from the period. It also outlines an entirely new approach to the study of literature as as the interaction of text and sonic practice, voice and noise, which will be of interest to scholars across literary studies, media theory, sound studies, and the history of science.

Tyler Whitney is an assistant professor of German at the University of Michigan.

Tyler Whitney (Author)

Eardrums.

Literary Modernism as Sonic Warfare

Cloth Text – $99.95

ISBN 978-0-8101-4022-6

Paper Text – $34.95

ISBN 978-0-8101-4021-9

Northwestern University Press

Publication Date June 2019

Literary Criticism

232 pages

Price: $24.00

# new books

Tyler Whitney

Eardrums.

Literary Modernism as Sonic Warfare

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, *War Poetry Archive, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive W-X, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DADA, Dadaïsme, Kafka, Franz, Modernisme, Visual & Concrete Poetry

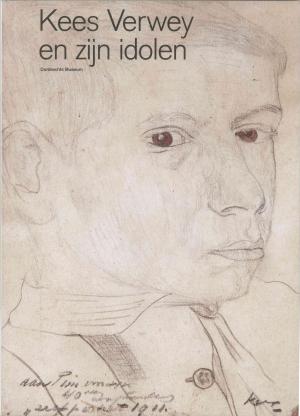

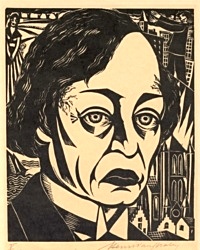

Antony Kok (1882 – 1969)

Antony Kok (1882 – 1969)

Antony Kok, was met Theo van Doesburg en Piet Mondriaan oprichter en medewerker van het avant-gardistische kunsttijdschrift De Stijl (1917 – 1932). Hij was vooral actief als dichter en schrijver van aforismen.

Kees Verwey (1900 -1995)

Tijdens zijn leven, dat bijna een eeuw beslaat, maakte de kunstenaar verschillende ontwikkelingen in de schilderkunst mee. Al op jonge leeftijd kwam hij in aanraking met het werk van George Breitner en Floris Verster. Ook werd hij beïnvloed door Franse (post-)impressionisten en later door de moderne kunst van o.a. Karel Appel en Pablo Picasso. Omringd door de kunst van zijn idolen wordt in deze nieuwe tentoonstelling de enorme vaardigheid en veelzijdigheid van de schilder Verwey duidelijk.

Na hun ontmoeting (in Haarlem in 1953) verklaarde Kees Verwey:

‘Antony Kok had me te pakken. Ruim een jaar ben ik met die ene man bezig geweest. Je zou zeggen dat zoiets ondenkbaar is, maar ik kon niet buiten de visie op die man. Het was een proces dat niet meer kon worden tegengehouden. Ik heb hem er wel eens over ondervraagd, toen zei hij: maar jij hebt die tekeningen niet gemaakt, ik heb ze gemaakt.’

In het eerste jaren van hun kennismaking maakte Verwey meer dan 30 portretten van Kok. De eerste serie zou begin jaren vijftig worden tentoongesteld in Amsterdam, Rotterdam en Haarlem. In 1955 was de serie uitgegroeid tot 40×1 en in Eindhoven te zien.

Lees meer over Kees Verwey, zijn vrienden en favoriete kunstenaars, zoals Karel Appel, Pablo Picasso, Edouard Vuillard, Floris Verster en Antony Kok in de bij de tentoonstelling verschenen publicatie:

Kees Verwey

en zijn idolen

Dordrechts Museum

2019

ISBN 978-90-71722-30-1

Redactie: Laura van den Hout, Judith Spijksma, Linda Janssen

Publicatie ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling ‘Kees Verwey en zijn idolen’, die van 14 juli 2019 tot en met 5 januari 2020 plaatsvindt in het Dordrechts Museum. De tentoonstelling kwam tot stand in samenwerking met Stichting Kees Verwey.

I N H O U D

6

Max van Rooy

Portretten als stillevens en het atelier als goudmijn

12

Karlijn de Jong

De moeder van de moderne kunst

Kees Verwey en De Onafhankelijken

22

Tijdlijn

26

Barbara Collé

Kijk ik naar de een, dan vlamt de ander

Over kleurenparen in Moeders theetafel en Het gele jakje van Kees Verwey, en Stilleven met boeken van Henri Frédéric Boot

34

Iduna Paalman

Sigaretje

36

Ester Naomi Perquin

Bes

38

Maartje Smits

Door je kind getekend

40

Maarten Buser

Pirouettes draaien op een idee

Kees Verwey en de literatuur

46

Jorne Vriens

Gekoesterde intimiteit

50

Max van Rooy

De onderzoekende kracht van het kijken

54

Sascha Broeders

De kunstenaar en de museumdirecteur

Kees Verwey volgens Jup de Groot, voormalig directeur van het Dordrechts Museum

56

Hanneke van Kempen en Jef van Kempen

‘Antony Kok had me te pakken’

66

Sandra Kisters

Het atelier van Kees Verwey – een kristal met vele facetten

75

Biografieën

76

Colofon

Tentoonstelling van 6 juli 2019 t/m 5 januari 2020

Kees Verwey en zijn idolen

Over Karel Appel, Pablo Picasso, Edouard Vuillard, Floris Verster, Antony Kok e.a.

Dordrechts Museum

Museumstraat 40, Dordrecht

3311 XP Dordrecht

www.dordrechtsmuseum.nl

‘Antony Kok had me te pakken’ sprak Kees Verwey

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Antony Kok, Archive K-L, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, DADA, Dada, De Stijl, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Hanneke van Kempen, Jef van Kempen, Kees Verwey, Kok, Antony, Piet Mondriaan, Theo van Doesburg

Stad

Verloren tijd, hoe schoon vind ik u weer,

waar elk herinnren wordt een nieuw verlangen.

o Steden-laan, wat zijn uw meisjes schoon.

Eens was ik jong, en ‘k ben niet jong gebleven…

Ik wandel bij de bomen die mijn jeugd

beveiligd hebben en haar jonge liefde.

Water is de adem van een meisjes mond

De stad is heet en droog als een begeerte.

Er is, tussen de dubble glans der laan,

er is een maan, er is een andre maan.

De een is de maan; de andere is gene maan.

Het paard wringt als een zilvren vis. En de ijlte is rood

maar roder zet de galm des voermans de ijlte uit.

Hitte.

Mijn vriend, gij hebt de geur der grote magazijnen.

Zo zijn er meisjes, schraal en met een witte neus.

Leeg schelpje aan nachtlijke ebbe: ik; maar de stad

in duizend dake’ als duizend diamanten.

Ik scheer de muren; – als een rechthoek ligt

naast mij mijn schaduw als een vals gedicht.

Menigte, uw geur bijt mijne lippen stuk.

o Menigte, gij doet mijne woorden bloeden.

Waarom te wenen in dit stenen woud?

Gij zult regeren als gij weet te lachen.

Jaag naar huis, o hart: gij vindt er

volle schotelen aan leed.

Stad: eind-punt; vierkant; rust en zekerheid.

‘k Zet me op een paal; ik wacht de roep der ijlte.

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

Stad

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Gij draagt een schone vlechte haar…

Gij draagt een schone vlechte haar

allangs uw lage leên…

– Het is een trage dag voorwaar

van weiflen en van wenen.

Het is een lengende avond van

mis-troosten en mis-prijzen.

’t Is of de dag niet sterven kan

en of geen nacht kan grijzen…

– Gij gaat mijn duister huis voorbij,

verlangenloos en rechte;

ik rade uw naakte, magre dij;

ik zie uw donkre vlechte.

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

Gij draagt een schone vlechte haar…

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Gelijk een arme, blinde hond

Geljk een arme, blinde hond

van alle troost verstoken,

dwaal ‘k door de zoele avond rond

en ruik de lente-roken.

Er waart – lijk om een vrouwe-kleed

waar oude driften in hangen –

er waart een geur van schamper leed

en van huilend-moe verlangen.

En ‘k dwaal, een blinde hond gelijk,

door dralige lente-roken,

mijn hart van alle liefden rijk,

mijn hart van liefde verstoken.

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

Gelijk een arme, blinde hond

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Kind met het bleek gelaat

Kind met het bleek gelaat, dat van uw wijde blikken

geen liefde in mat gebaar noch in lede ogen ziet,

maar in uw zedig kleed uw knieën weet te schikken

zó, dat me te elken male een laaie drift doorschiet:

gij zult het nimmer aan mijn vrome woorden weten

hoe mijn begeren om uw kleren dolen dorst;

maar ìk draag in me-zelf de wonde, zelf gereten,

waarvan de koortse rilt en davert door mijn borst.

Want ‘k heb de straffe zélf in ‘t lillend vlees geslagen;

ik heb een spijt’ge spot gehamerd in mijn brein…

– Gij echter, ga voorbij, arm kind, en zónder vragen:

ik haat u om dees geert’, die ‘k minne om deze pijn…

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

Kind met het bleek gelaat

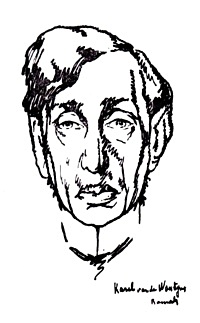

Portret: Karel van de Woestijne, Ramah – Journal Het Roode Zeil, 15 April 1920

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Vlaanderen, o welig huis

Vlaandren, o welig huis waar we zijn als genoden

aan rijke taaflen! – daar nu glooiend zijn de weiên

van zomer-granen, die hunne aêmende ebbe breien

naar malvend Ooste’ en statig dagerade-roden,

dewijl de morge’ ontwaakt ten hemel en ter Leië -:

wie kan u weten, en in ‘t harte niet verblijên;

niet danke’ om dagen, schoon als jonge zege-goden,

gelijk een beedlaar dankt om warme tarwe-broden?…

o Vlaandren, blijde van uw gevens-rede handen,

zwaar, daar ge delend gaat, in paarse en gele wade,

der krachten die uw schoot als rodend ooft beladen.

– Vlaandren, wie wéet u en de zomer-dageraden,

en voelt geen rilde liefde in zijne leden branden

‘lijk deze morgen door de veië Leië-landen?

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

Vlaanderen, o welig huis

Portret van Karel van de Woestijne (1937) door Henri van Straten (1892 – 1944)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

The Flying Man

The Ethnologist looked at the bhimraj feather thoughtfully. “They seemed loth to part with it,” he said.

“It is sacred to the Chiefs,” said the lieutenant; “just as yellow silk, you know, is sacred to the Chinese Emperor.”

The Ethnologist did not answer. He hesitated. Then opening the topic abruptly, “What on earth is this cock-and-bull story they have of a flying man?”

The lieutenant smiled faintly. “What did they tell you?”

The lieutenant smiled faintly. “What did they tell you?”

“I see,” said the Ethnologist, “that you know of your fame.”

The lieutenant rolled himself a cigarette. “I don’t mind hearing about it once more. How does it stand at present?”

“It’s so confoundedly childish,” said the Ethnologist, becoming irritated. “How did you play it off upon them?”

The lieutenant made no answer, but lounged back in his folding-chair, still smiling.

“Here am I, come four hundred miles out of my way to get what is left of the folk-lore of these people, before they are utterly demoralised by missionaries and the military, and all I find are a lot of impossible legends about a sandy-haired scrub of an infantry lieutenant. How he is invulnerable — how he can jump over elephants — how he can fly. That’s the toughest nut. One old gentleman described your wings, said they had black plumage and were not quite as long as a mule. Said he often saw you by moonlight hovering over the crests out towards the Shendu country. — Confound it, man!”

The lieutenant laughed cheerfully. “Go on,” he said. “Go on.”

The Ethnologist did. At last he wearied. “To trade so,” he said, “on these unsophisticated children of the mountains. How could you bring yourself to do it, man?”

“I’m sorry,” said the lieutenant, “but truly the thing was forced upon me. I can assure you I was driven to it. And at the time I had not the faintest idea of how the Chin imagination would take it. Or curiosity. I can only plead it was an indiscretion and not malice that made me replace the folk-lore by a new legend. But as you seem aggrieved, I will try and explain the business to you.

“It was in the time of the last Lushai expedition but one, and Walters thought these people you have been visiting were friendly. So, with an airy confidence in my capacity for taking care of myself, he sent me up the gorge — fourteen miles of it — with three of the Derbyshire men and half a dozen Sepoys, two mules, and his blessing, to see what popular feeling was like at that village you visited. A force of ten — not counting the mules — fourteen miles, and during a war! You saw the road?”

“Road!” said the Ethnologist.

“It’s better now than it was. When we went up we had to wade in the river for a mile where the valley narrows, with a smart stream frothing round our knees and the stones as slippery as ice. There it was I dropped my rifle. Afterwards the Sappers blasted the cliff with dynamite and made the convenient way you came by. Then below, where those very high cliffs come, we had to keep on dodging across the river — I should say we crossed it a dozen times in a couple of miles.

“We got in sight of the place early the next morning. You know how it lies, on a spur halfway between the big hills, and as we began to appreciate how wickedly quiet the village lay under the sunlight, we came to a stop to consider.

“At that they fired a lump of filed brass idol at us, just by way of a welcome. It came twanging down the slope to the right of us where the boulders are, missed my shoulder by an inch or so, and plugged the mule that carried all the provisions and utensils. I never heard such a death-rattle before or since. And at that we became aware of a number of gentlemen carrying matchlocks, and dressed in things like plaid dusters, dodging about along the neck between the village and the crest to the east.

“‘Right about face,’ I said. ‘Not too close together.’

“And with that encouragement my expedition of ten men came round and set off at a smart trot down the valley again hitherward. We did not wait to save anything our dead had carried, but we kept the second mule with us — he carried my tent and some other rubbish — out of a feeling of friendship.

“So ended the battle — ingloriously. Glancing back, I saw the valley dotted with the victors, shouting and firing at us. But no one was hit. These Chins and their guns are very little good except at a sitting shot. They will sit and finick over a boulder for hours taking aim, and when they fire running it is chiefly for stage effect. Hooker, one of the Derbyshire men, fancied himself rather with the rifle, and stopped behind for half a minute to try his luck as we turned the bend. But he got nothing.

“I’m not a Xenophon to spin much of a yarn about my retreating army. We had to pull the enemy up twice in the next two miles when he became a bit pressing, by exchanging shots with him, but it was a fairly monotonous affair — hard breathing chiefly — until we got near the place where the hills run in towards the river and pinch the valley into a gorge. And there we very luckily caught a glimpse of half a dozen round black heads coming slanting-ways over the hill to the left of us — the east that is — and almost parallel with us.

“At that I called a halt. ‘Look here,’ says I to Hooker and the other Englishmen; ‘what are we to do now?’ and I pointed to the heads.

“‘Headed orf, or I’m a nigger,’ said one of the men.

“‘We shall be,’ said another. ‘You know the Chin way, George?’

“‘They can pot every one of us at fifty yards,’ says Hooker, ‘in the place where the river is narrow. It’s just suicide to go on down.’

“I looked at the hill to the right of us. It grew steeper lower down the valley, but it still seemed climbable. And all the Chins we had seen hitherto had been on the other side of the stream.

“‘It’s that or stopping,’ says one of the Sepoys.

“So we started slanting up the hill. There was something faintly suggestive of a road running obliquely up the face of it, and that we followed. Some Chins presently came into view up the valley, and I heard some shots. Then I saw one of the Sepoys was sitting down about thirty yards below us. He had simply sat down without a word, apparently not wishing to give trouble. At that I called a halt again; I told Hooker to try another shot, and went back and found the man was hit in the leg. I took him up, carried him along to put him on the mule — already pretty well laden with the tent and other things which we had no time to take off. When I got up to the rest with him, Hooker had his empty Martini in his hand, and was grinning and pointing to a motionless black spot up the valley. All the rest of the Chins were behind boulders or back round the bend. ‘Five hundred yards,’ says Hooker, ‘if an inch. And I’ll swear I hit him in the head.’

“So we started slanting up the hill. There was something faintly suggestive of a road running obliquely up the face of it, and that we followed. Some Chins presently came into view up the valley, and I heard some shots. Then I saw one of the Sepoys was sitting down about thirty yards below us. He had simply sat down without a word, apparently not wishing to give trouble. At that I called a halt again; I told Hooker to try another shot, and went back and found the man was hit in the leg. I took him up, carried him along to put him on the mule — already pretty well laden with the tent and other things which we had no time to take off. When I got up to the rest with him, Hooker had his empty Martini in his hand, and was grinning and pointing to a motionless black spot up the valley. All the rest of the Chins were behind boulders or back round the bend. ‘Five hundred yards,’ says Hooker, ‘if an inch. And I’ll swear I hit him in the head.’

“I told him to go and do it again, and with that we went on again.

“Now the hillside kept getting steeper as we pushed on, and the road we were following more and more of a shelf. At last it was mere cliff above and below us. ‘It’s the best road I have seen yet in Chin Lushai land,’ said I to encourage the men, though I had a fear of what was coming.

“And in a few minutes the way bent round a corner of the cliff. Then, finis! the ledge came to an end.

“As soon as he grasped the position one of the Derbyshire men fell a-swearing at the trap we had fallen into. The Sepoys halted quietly. Hooker grunted and reloaded, and went back to the bend.

“Then two of the Sepoy chaps helped their comrade down and began to unload the mule.

“Now, when I came to look about me, I began to think we had not been so very unfortunate after all. We were on a shelf perhaps ten yards across it at widest. Above it the cliff projected so that we could not be shot down upon, and below was an almost sheer precipice of perhaps two or three hundred feet. Lying down we were invisible to anyone across the ravine. The only approach was along the ledge, and on that one man was as good as a host. We were in a natural stronghold, with only one disadvantage, our sole provision against hunger and thirst was one live mule. Still we were at most eight or nine miles from the main expedition, and no doubt, after a day or so, they would send up after us if we did not return.

“After a day or so . . . ”

The lieutenant paused. “Ever been thirsty, Graham?”

“Not that kind,” said the Ethnologist.

“H’m. We had the whole of that day, the night, and the next day of it, and only a trifle of dew we wrung out of our clothes and the tent. And below us was the river going giggle, giggle, round a rock in mid stream. I never knew such a barrenness of incident, or such a quantity of sensation. The sun might have had Joshua’s command still upon it for all the motion one could see; and it blazed like a near furnace. Towards the evening of the first day one of the Derbyshire men said something — nobody heard what — and went off round the bend of the cliff. We heard shots, and when Hooker looked round the corner he was gone. And in the morning the Sepoy whose leg was shot was in delirium, and jumped or fell over the cliff. Then we took the mule and shot it, and that must needs go over the cliff too in its last struggles, leaving eight of us.

“We could see the body of the Sepoy down below, with the head in the water. He was lying face downwards, and so far as I could make out was scarcely smashed at all. Badly as the Chins might covet his head, they had the sense to leave it alone until the darkness came.

“At first we talked of all the chances there were of the main body hearing the firing, and reckoned whether they would begin to miss us, and all that kind of thing, but we dried up as the evening came on. The Sepoys played games with bits of stone among themselves, and afterwards told stories. The night was rather chilly. The second day nobody spoke. Our lips were black and our throats afire, and we lay about on the ledge and glared at one another. Perhaps it’s as well we kept our thoughts to ourselves. One of the British soldiers began writing some blasphemous rot on the rock with a bit of pipeclay, about his last dying will, until I stopped it. As I looked over the edge down into the valley and saw the river rippling I was nearly tempted to go after the Sepoy. It seemed a pleasant and desirable thing to go rushing down through the air with something to drink — or no more thirst at any rate — at the bottom. I remembered in time, though, that I was the officer in command, and my duty to set a good example, and that kept me from any such foolishness.

“Yet, thinking of that, put an idea into my head. I got up and looked at the tent and tent ropes, and wondered why I had not thought of it before. Then I came and peered over the cliff again. This time the height seemed greater and the pose of the Sepoy rather more painful. But it was that or nothing. And to cut it short, I parachuted.

“I got a big circle of canvas out of the tent, about three times the size of that table-cover, and plugged the hole in the centre, and I tied eight ropes round it to meet in the middle and make a parachute. The other chaps lay about and watched me as though they thought it was a new kind of delirium. Then I explained my notion to the two British soldiers and how I meant to do it, and as soon as the short dusk had darkened into night, I risked it. They held the thing high up, and I took a run the whole length of the ledge. The thing filled with air like a sail, but at the edge I will confess I funked and pulled up.

“As soon as I stopped I was ashamed of myself — as well I might be in front of privates — and went back and started again. Off I jumped this time — with a kind of sob, I remember — clean into the air, with the big white sail bellying out above me.

“I must have thought at a frightful pace. It seemed a long time before I was sure that the thing meant to keep steady. At first it heeled sideways. Then I noticed the face of the rock which seemed to be streaming up past me, and me motionless. Then I looked down and saw in the darkness the river and the dead Sepoy rushing up towards me. But in the indistinct light I also saw three Chins, seemingly aghast at the sight of me, and that the Sepoy was decapitated. At that I wanted to go back again.

“Then my boot was in the mouth of one, and in a moment he and I were in a heap with the canvas fluttering down on the top of us. I fancy I dashed out his brains with my foot. I expected nothing more than to be brained myself by the other two, but the poor heathen had never heard of Baldwin, and incontinently bolted.

“I struggled out of the tangle of dead Chin and canvas, and looked round. About ten paces off lay the head of the Sepoy staring in the moonlight. Then I saw the water and went and drank. There wasn’t a sound in the world but the footsteps of the departing Chins, a faint shout from above, and the gluck of the water. So soon as I had drunk my full I started off down the river.

“That about ends the explanation of the flying man story. I never met a soul the whole eight miles of the way. I got to Walters’ camp by ten o’clock, and a born idiot of a sentinel had the cheek to fire at me as I came trotting out of the darkness. So soon as I had hammered my story into Winter’s thick skull, about fifty men started up the valley to clear the Chins out and get our men down. But for my own part I had too good a thirst to provoke it by going with them.

“You have heard what kind of a yarn the Chins made of it. Wings as long as a mule, eh? — And black feathers! The gay lieutenant bird! Well, well.”

The lieutenant meditated cheerfully for a moment. Then he added, “You would scarcely credit it, but when they got to the ridge at last, they found two more of the Sepoys had jumped over.”

“The rest were all right?” asked the Ethnologist.

“Yes,” said the lieutenant; “the rest were all right, barring a certain thirst, you know.”

And at the memory he helped himself to soda and whisky again.

Herbert George Wells

(1866-1946)

The Stolen Bacillus and other incidents

short stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Archive W-X, H.G. Wells, Tales of Mystery & Imagination, Wells, H.G.

De Dichter

Geen zomer-schaâuwe is schoon als ‘t beeld, in volle teilen,

der welv’ge melk die ront, van roerig licht ommaald.

Mijn schamel huis, waar zoel een geur van peren draalt,

weegt teerder in mijn schroom dan ‘t hele herfst-verwijlen.

En, waar van ‘t winter-dak een schone mane daalt,

‘n weifelt ijl een hele lente in hare wijle,

o mijn gezóende blik, en moe van eigen-peilen?

– Geen zoen is goed, dan die vergeten zorg verhaalt…

Aldus wie zijn geluk in ‘t noden van een teken

gelijk een geurig brood meewarig-blij durft breken,

en nut de zuurste zemel-korst in heil’ge waan;

om bij het heil dat weende en ‘t vreemde leed dat lachte,

en in de hoede van uw deemstren, o Gedachte,

eens, als een schone vraag, glim-lachend heen te gaan.

De Boom-Gaard der Vogelen en der Vruchten (1903 – 1905)

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

De Dichter

Portret van Karel van de Woestijne (1937) door Henri van Straten (1892 – 1944)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Er komt iemand bij mij

Er komt iemand bij mij, die ‘k nimmer zag,

en uit-der-mate vriendlijk, die mij zegt:

‘Gij weet, ik berg iemand in mijne woon.

Neen: er verbergt zich iemand in mijn woon.

Ik zie hem niet, maar ben in hem begaan.

Ik ken hem, en hij is mijn liefst bezit…’

– Ik durf niet zeggen dat die vreemdling liegt.

Ik durf niet zeggen dat zijn gast de mijne is. Ach!

ik durf niet zèggen dat hij niet bestaat, misschien.

Want hij bestaat in mij.

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

Er komt iemand bij mij

Portret: Karel van de Woestijne, Ramah – Journal Het Roode Zeil, 15 April 1920

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature