Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

1936: Dmitri Shostakovich, just thirty years old, reckons with the first of three conversations with power that will irrevocably shape his life.

Stalin, hitherto a distant figure, has suddenly denounced the young composer’s latest opera. Certain he will be exiled to Siberia (or, more likely, shot dead on the spot), Shostakovich reflects on his predicament, his personal history, his parents, his daughter—all of those hanging in the balance of his fate. And though a stroke of luck prevents him from becoming yet another casualty of the Great Terror, he will twice more be swept up by the forces of despotism: coerced into praising the Soviet state at a cultural conference in New York in 1948, and finally bullied into joining the Party in 1960. All the while, he is compelled to constantly weigh the specter of power against the integrity of his music. An extraordinary portrait of a relentlessly fascinating man, The Noise of Time is a stunning meditation on the meaning of art and its place in society.

Stalin, hitherto a distant figure, has suddenly denounced the young composer’s latest opera. Certain he will be exiled to Siberia (or, more likely, shot dead on the spot), Shostakovich reflects on his predicament, his personal history, his parents, his daughter—all of those hanging in the balance of his fate. And though a stroke of luck prevents him from becoming yet another casualty of the Great Terror, he will twice more be swept up by the forces of despotism: coerced into praising the Soviet state at a cultural conference in New York in 1948, and finally bullied into joining the Party in 1960. All the while, he is compelled to constantly weigh the specter of power against the integrity of his music. An extraordinary portrait of a relentlessly fascinating man, The Noise of Time is a stunning meditation on the meaning of art and its place in society.

Julian Barnes is the author of twenty previous books. He has received the Man Booker Prize, the Somerset Maugham Award, the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, the David Cohen Prize for Literature and the E. M. Forster Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters; in France, the Prix Médicis and the Prix Femina; and in Austria, the State Prize for European Literature. In 2004 he was named Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture. His work has been translated into more than forty languages. He lives in London.

One of the Best Books of the Year: San Francisco Chronicle

“This story is truly amazing . . . an arc of human degradation without violence (the threat of violence, of course, everywhere). . . . The whole Kafka madhouse brought to life.”—Jeremy Denk, The New York Times Book Review

The Noise of Time

A Novel

By Julian Barnes

Part of Vintage International

Literary Fiction

Paperback

Publisher Penguin Random House

June 2017,

224 Pages

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Dmitri Shostakovich, Julian Barnes, The Art of Reading

Röhrensiedlung oder Gotik

Röhrensiedlung oder Gotik

Jazz, Jazzband, Bandwurm. Der Burschensaft thomasinischer Printengänger vel expressive Spekulatiusarchitekten ist bei der Renovierung seiner durchlaufend honorierten Arbeiten auf den Kriminalvorwurf No. 2333/1920 geh. gestoßen. Der Podrekt 2333/1920 geh. wurde am 15. Januar 11.30 vorm. persönlich durch den Komunalbaueleven moritz remond eingebacken und verhandelt die Besandung des Röhrensystems durch den Auflauf des Kölner Doms.

Nachdem die philoporne Klingel des Bundes zu dem Podrekt durch Ansaugen von Gefrierhosen Stellung genommen, erklärt der außerhalb der Haftpflicht stechende Pornodidakt rauchlose erst die Einfühlung der Kommunalgotik als Abbau der Ehe und droht mit der Kommunalisierung seiner Frau. Während albert einstein und die Sozialistin auguste rodin Glückwunschtelegramme häkeln, sägt die Zentrale w/3 der Bewegung dada für das einjährig-freiwillige Diözesan-Derby einen Vergleich auf dem Boden der Röhrenarchitektur aus. Die Abstimmungsgebiete werden sich bestimmen lassen, ob die Gewölbeparteien des Eiffelturmes zu vergraben sind, der ein freigelegter Keller ist und den Verstimmungen des Betriebröhrengesetzentwurfes widerspricht. Der Kosmopolid leo seiwet hat seine Geliebte geheiratet. Das Jubelpaar hat sich an die Zentrale w/3 Abt.

Röhrenarchitinktur mit dem Büttel gesandt, der durch Anbringen von Röhrenfarcaden an den Brandmauern und Häuserhintern seines Viertels dem Tag ein Psychoparallelepitaph setzt. Der Geheimurn “Stätteerweiterung” des Dada Maschke B.D.B. hat in den Bäumen des städt. Ziertierentwertungsverwalts (Nippes, Schiefersburgerweg 150-154, Tel. A4491) eine plananatomische Ornamentalwarte verrichtet. Das Institut beabsichtigt mit einer Aufzahl Entwachsungen, abnormer Haarungen, Kotsteinerungen und Perlbildungen am weiblichen Akt den Ornamentalkanon der Röhrenaphrotektur auszukauen. Das Kinoweilchen clever hasenfalter wird weite’ wiede’ von seinem Sohn begossen. hasenwalter ist durch Verführung des Dadaisten johann r. rubiner in der Röhrensiedlung Sylt mit seinem Sohn konstipiert worden. Als Folge des Januar-hochwassers sind die Vasen der Dadaistin rosala meerfeld geplatzt. Die Konsumentenvereinigung hat daher die Kanarisierung des Dezernentenwesens durch Harzer Roller beantragt. Trotzdem hat der Propagandist der Interjektion Prof. wilh. fachinger – bonn in studentischer Sitzung der Bonnendiplombeflissenen die expressionistische Ausmalung seiner Gattin verelendet.

Das ergriffene Altarwerk “mein einzige Passion” wurde nachm. 3.15 vom Erzbischof Dr. schultze zweimal durch die Offizien des Domkapitels geweht. Der Satinist hans arp, Emissär des Internationalen Aktionsausschusses “D” hat der Nitte des Philatheleten Prof. leopold von schäler den amor intellektualis dei vertragen. Dagegen wird der verliebte Philathelet in seiner nächsten Puberkation seiner Nitte die Vorgüsse der Augustinischen Röhrensynthese geleisen. arp glaubt zu dem Ergebnis zu kommen, daß die Gotik eine erektive Vomations-erscheinung der Zahnfäule ist, und bereits eine Dränagedräsine mit Hilfe des Röhrensystems.

Die Ortsnucke Zürich der dadaistischen Bewegung hat 920 deutsche Roßhaarzahnwürste an die rheinischen Commilitonen Sozial-Kompottstudierenden ausgeglichen. Wir sollen die Röhrenarchitektur an und in der Röhre. Röhrenbein. Pegoud steht Röhre. Die – anni – besant steht Röhre. Wieland Heartfield (aus dem Englischen unterschlagen von der Gesellschaft der Künste in Köln Ausgabe “A”) steht Röhre. Steht Röhren! Collaborate! Stehröhre:

Die Gotik ist der grimassierende Exhibitionalis der Klotzeier.

Der Gotiker ist der Selbstmörder in Geschlechtsverkleidung. Collabor, Bohrrohr, die Harmröhre röhrt, r r r r r rumpfsdada.

Johannes Theodor Baargeld

(1892-1927)

‘Röhrensiedlung oder Gotik’

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Baargeld, Johannes Theodor, Dada, DADA, Dadaïsme

Paul Auster, Emily Fridlund, Mohsin Hamid, Fiona Mozley, George Saunders and Ali Smith are announced as the six shortlisted authors for the 2017 Man Booker Prize for Fiction.

Their names were announced by 2017 Chair of judges, Lola, Baroness Young, at a press conference at the offices of Man Group, the prize sponsor.

Their names were announced by 2017 Chair of judges, Lola, Baroness Young, at a press conference at the offices of Man Group, the prize sponsor.

The judges remarked that the novels, each in its own way, challenge and subtly shift our preconceptions — about the nature of love, about the experience of time, about questions of identity and even death.

Two novels from independent publishers, Faber & Faber and Bloomsbury, are shortlisted, alongside two from Penguin Random House imprint Hamish Hamilton and two from Hachette imprints, Weidenfeld & Nicolson and JM Originals.

The 2017 shortlist of six novels is:

4321 by Paul Auster (US) (Faber & Faber)

History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund (US) (Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid (UK-Pakistan) (Hamish Hamilton)

Elmet by Fiona Mozley (UK) (JM Originals)

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders (US) (Bloomsbury Publishing)

Autumn by Ali Smith (UK) (Hamish Hamilton)

The judging panel, chaired by Lola, Baroness Young, consists of: the literary critic, Lila Azam Zanganeh; the Man Booker Prize shortlisted novelist, Sarah Hall; the artist, Tom Phillips CBE RA; and the travel writer and novelist, Colin Thubron CBE.

The judging panel, chaired by Lola, Baroness Young, consists of: the literary critic, Lila Azam Zanganeh; the Man Booker Prize shortlisted novelist, Sarah Hall; the artist, Tom Phillips CBE RA; and the travel writer and novelist, Colin Thubron CBE.

The 2017 winner will be announced on Tuesday 17 October in London’s Guildhall, at a dinner that brings together the shortlisted authors and many well-known figures from the literary world. The ceremony will be broadcasted by the BBC.

The shortlisted authors will each receive £2,500 and a specially bound edition of their book. The winner will receive a further £50,000 and can expect international recognition.

The Man Booker Prize 2017 shortlist:

4 3 2 1 by Paul Auster (US) (Faber & Faber)

History of Wolves by Emily Fridlund (US) (Weidenfeld & Nicolson)

Exit West by Mohsin Hamid (Pakistan-UK) (Hamish Hamilton)

Elmet by Fiona Mozley (UK) (JM Originals)

Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders (US) (Bloomsbury Publishing)

Autumn by Ali Smith (UK) (Hamish Hamilton)

The Man Booker Prize 2017

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, Literary Events, Paul Auster

Global Discontents is a compelling set of interviews with Noam Chomsky, who identifies the “dry kindling” of discontent around the world that could soon catch fire.

In wide-ranging interviews with David Barsamian, his longtime interlocutor, Noam Chomsky asks us to consider “the world we are leaving to our grandchildren”: one imperiled by the escalation of climate change and the growing potential for nuclear war. If the current system is incapable of dealing with these threats, he argues, it’s up to us to radically change it.

In wide-ranging interviews with David Barsamian, his longtime interlocutor, Noam Chomsky asks us to consider “the world we are leaving to our grandchildren”: one imperiled by the escalation of climate change and the growing potential for nuclear war. If the current system is incapable of dealing with these threats, he argues, it’s up to us to radically change it.

These ten interviews, conducted from 2013 to 2016, examine the latest developments around the globe: the devastation of Syria, the reach of state surveillance, growing anger over economic inequality, the place of religion in American political culture, and the bitterly contested 2016 U.S. presidential election. In accompanying personal reflections on his Philadelphia childhood and his eighty-seventh birthday, Chomsky also describes his own intellectual journey and the development of his uncompromising stance as America’s premier dissident intellectual.

Noam Chomsky is the author of numerous bestselling political works, including Hegemony or Survival and Failed States. A professor emeritus of linguistics and philosophy at MIT, he is widely credited with having revolutionized modern linguistics. He lives outside Boston, Massachusetts.

David Barsamian, director of the award-winning and widely syndicated Alternative Radio, is a winner of the Lannan Foundation’s Cultural Freedom Fellowship and the ACLU’s Upton Sinclair Award for independent journalism. He lives in Boulder, Colorado.

Global Discontents

Conversations on the Rising Threats to Democracy

Noam Chomsky: Interviews with David Barsamian

Trade Paperback

$18.00

Metropolitan Books

Henry Holt and Co.

12/05/2017

ISBN: 9781250146182

240 Pages

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, MONTAIGNE, Noam Chomsky

The story of two girls and the wild year that will cost one her life, and define the other’s for decades.

Everything about fifteen-year-old Cat’s new town in rural Michigan is lonely and off-kilter until she meets her neighbor, the manic, beautiful, pill-popping Marlena. Cat is quickly drawn into Marlena’s orbit and as she catalogues a litany of firsts—first drink, first cigarette, first kiss, first pill—Marlena’s habits harden and calcify. Within the year, Marlena is dead, drowned in six inches of icy water in the woods nearby. Now, decades later, when a ghost from that pivotal year surfaces unexpectedly, Cat must try again to move on, even as the memory of Marlena calls her back.

Everything about fifteen-year-old Cat’s new town in rural Michigan is lonely and off-kilter until she meets her neighbor, the manic, beautiful, pill-popping Marlena. Cat is quickly drawn into Marlena’s orbit and as she catalogues a litany of firsts—first drink, first cigarette, first kiss, first pill—Marlena’s habits harden and calcify. Within the year, Marlena is dead, drowned in six inches of icy water in the woods nearby. Now, decades later, when a ghost from that pivotal year surfaces unexpectedly, Cat must try again to move on, even as the memory of Marlena calls her back.

Told in a haunting dialogue between past and present, Marlena is an unforgettable story of the friendships that shape us beyond reason and the ways it might be possible to pull oneself back from the brink.

“It’s still so early in 2017 that calling something a best debut novel of the year is a dicey thing to try and do. But if the Lorrie Moore blurb on the front cover doesn’t tip you off that Julie Buntin’s Marlena is a book you should be paying attention to, the fact that the author created something that could easily be called the millennial Midwestern version of the celebrated Elena Ferrante Neapolitan Novels crossed with Robin Wasserman’s great Girls on Fire, should do the trick.” –Rolling Stone

Julie Buntin is from northern Michigan. Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Cosmopolitan, O, The Oprah Magazine, Slate, Electric Literature, and One Teen Story, among other publications. She teaches fiction at Marymount Manhattan College, and is the director of writing programs at Catapult. She lives in Brooklyn, New York. Marlena is her debut novel.

MARLENA

By Julie Buntin

Hardcover

$26.00

Henry Holt and Co.

04/04/2017

ISBN: 9781627797641

288 Pages

Trade Paperback

$16.00

Picador

04/03/2018

ISBN: 9781250160157

288 Pages

book news

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News

Pigeonholed in popular memory as a Jazz Age epicurean, a playboy, and an emblem of the Lost Generation, F. Scott Fitzgerald was at heart a moralist struck by the nation’s shifting mood and manners after World War I.

In Paradise Lost, David Brown contends that Fitzgerald’s deepest allegiances were to a fading antebellum world he associated with his father’s Chesapeake Bay roots. Yet as a midwesterner, an Irish Catholic, and a perpetually in-debt author, he felt like an outsider in the haute bourgeoisie haunts of Lake Forest, Princeton, and Hollywood—places that left an indelible mark on his worldview.

In Paradise Lost, David Brown contends that Fitzgerald’s deepest allegiances were to a fading antebellum world he associated with his father’s Chesapeake Bay roots. Yet as a midwesterner, an Irish Catholic, and a perpetually in-debt author, he felt like an outsider in the haute bourgeoisie haunts of Lake Forest, Princeton, and Hollywood—places that left an indelible mark on his worldview.

In this comprehensive biography, Brown reexamines Fitzgerald’s childhood, first loves, and difficult marriage to Zelda Sayre. He looks at Fitzgerald’s friendship with Hemingway, the golden years that culminated with Gatsby, and his increasing alcohol abuse and declining fortunes which coincided with Zelda’s institutionalization and the nation’s economic collapse.

Placing Fitzgerald in the company of Progressive intellectuals such as Charles Beard, Randolph Bourne, and Thorstein Veblen, Brown reveals Fitzgerald as a writer with an encompassing historical imagination not suggested by his reputation as “the chronicler of the Jazz Age.” His best novels, stories, and essays take the measure of both the immediate moment and the more distant rhythms of capital accumulation, immigration, and sexual politics that were moving America further away from its Protestant agrarian moorings. Fitzgerald wrote powerfully about change in America, Brown shows, because he saw it as the dominant theme in his own family history and life.

David S. Brown is Raffensperger Professor of History at Elizabethtown College.

“[An] incisive biography.”—The New Yorker

“Paradise Lost accomplishes much in its aim to contextualize Fitzgerald within both American historical and literary historical parameters. This new biography manages to get past the trappings of Fitzgerald’s boozy flapper-era persona and to credit his talent for taking the pulse of the America in which he lived.”—Christina Hunt Mahoney, The Irish Times

Paradise Lost

A Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald

David S. Brown

424 pag. – 2017

Harvard University Press

Belknap Press

Isbn 9780674504820

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, BIOGRAPHY, Fitzgerald, F. Scott

Who hasn’t heard of Proust’s famous questionnaire? The writer’s answers have travelled across time and all around the world, but people have forgotten that they came from an album called Confessions that belonged to Antoinette Faure, daughter of the future French President.

Marcel Proust didn’t realize that, by taking part in what was a fashionable parlour game, he would be revealing clues about his teenage self. His answers have elicited commentaries but have never been contextualised or compared, never dated accurately.

Marcel Proust didn’t realize that, by taking part in what was a fashionable parlour game, he would be revealing clues about his teenage self. His answers have elicited commentaries but have never been contextualised or compared, never dated accurately.

Where and when did he answer this questionnaire? What sort of boy was he at the time? And most significantly, how much of that period and those friendships fed into his future work? What traces are left of Gilberte on the Champs-Élysées, Albertine’s little group and the “young girls in flower”?

Évelyne Bloch-Dano conducted this enquiry over many years. Using sometimes tiny clues, she managed to identify Antoinette’s other friends, some of whom may have known Proust.

A whole world came to life, revolving around the daughters of the late nineteenth-century bourgeoisie, many of them with connections to Le Havre like the Faure family. Some boys appear too. Through their ideas, their books, their customs, what they study and what they dream of, the portrait of a whole generation emerges.

Marcel Proust’s generation. Young people born to the defeat at Sedan in 1870, in a vengeful republican France. The generation of General Boulanger, of political scandal and the Dreyfus Affair, but also of schools for girls, electricity, Great Exhibitions and the Belle époque. And later the First World War.

The biographer and essayist Évelyne Bloch-Dano is the author of several prize-winning and widely translated books, including most notably biographies of Madame Zola (1997, Grand Prix of Elle readers), Madame Proust (2004, Prix Renaudot for an essay), Le Dernier Amour de George Sand (2010), but also Jardins de papier (2015), and the more personal La Biographe (2007) and Porte de Champerret (2013).

Evelyne Bloch-Dano: Une jeunesse de Marcel Proust

(Marcel Proust as a young man by Évelyne Bloch-Dano)

Collection: La Bleue

Éditions Stock Paris

Parution: 20/09/2017

304 pages

Format: 135 x 215 mm

EAN: 9782234075696

Prix: €19.50

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, BIOGRAPHY, FDM in Paris, Marcel Proust, Proust, Marcel

A wickedly funny and life-affirming coming-of-age roadtrip story – winner of France’s biggest prize for teen and YA fiction Mireille, Astrid and Hakima have just been voted the three ugliest girls in school by their classmates on Facebook. But does that mean they’re going to sit around crying about it? . . .

Well, maybe a little, but not for long! Climbing onto their bikes, the friends set off on a summer roadtrip to Paris. The girls will find fame, friendship and happiness on their journey, and still have time to eat a mountain of food (and drink the odd glass of wine) along the way.

Well, maybe a little, but not for long! Climbing onto their bikes, the friends set off on a summer roadtrip to Paris. The girls will find fame, friendship and happiness on their journey, and still have time to eat a mountain of food (and drink the odd glass of wine) along the way.

But will they really be able to leave all their troubles behind? Piglettes is a hilarious, beautiful and uplifting story of three girls who are determined not to let online bullying get them down.

Clémentine Beauvais (born 1989) is a French children’s author living in the UK. She started reading children’s books early, and somehow never stopped. Now she writes her own, in both French and English, for a variety of ages, and is a lecturer in English and Education at the University of York.

Piglettes won four prizes in France, including the biggest children’s book prize, the Prix Sorcières. Film and stage versions are also in production. Now Clémentine has translated her book into English!

Clementine Beauvais

Piglettes

Publisher: Pushkin Children’S Books

Engelsh

288 pages

paperback

ISBN 9781782691204

june 2017

Reading age: 12 years and older

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Illustrators, Illustration

Volgens Pierre Maréchal was de Brabantse dichter Frans Babylon een zieke poète maudit die zowel de poëzie als de kunst stimuleerde te vernieuwen. Brabant liep sterk achter bij de ontwikkelingen.

Volgens Pierre Maréchal was de Brabantse dichter Frans Babylon een zieke poète maudit die zowel de poëzie als de kunst stimuleerde te vernieuwen. Brabant liep sterk achter bij de ontwikkelingen.

Uiteindelijk verwierp hij de traditionele dichtstijlen en schreef hij gedichten op gevoel. Met vrienden vormde hij de Bredero-club en stimuleerde hij kunstenaars om zich verder te ontwikkelen. Babylon bevorderde eveneens de ontwikkeling van openbare kunstexposities voor groot publiek.

Naast Brabant en Amsterdam was Frankrijk een geliefde omgeving. Ondanks zijn bipolaire stoornis en dankzij zijn creativiteit bracht Frans Babylon veel tot stand.

Pierre Maréchal werkte onder meer voor de internationale trekvogel-bescherming. Ruim twintig jaar is hij actief bezig met poëzie. Hij schrijft en organiseert maandelijks diverse podia en optredens. De laatste jaren doet hij dit bij de PoëzieClub Eindhoven en de werkgroep ‘Boekenkast’. Frans Babylon – herinneringsgewijs is typisch zo’n onderwerp. Het is een project over een bekende en tegelijk een minder bekende dichter, wiens daden van betekenis waren voor de ontwikkeling van de poëzie en de kunsten in het zuiden van ons land.

Pierre L.Th.A. Maréchal

Frans Babylon – herinneringsgewijs

Biografie Frans Babylon,

pseudoniem van Franciscus Gerardus Jozef Obers (1924 – 1968)

ISBN: 978-94-0223-720-7

Paperback 12,5 x 20 cm

186 pag. – 2017

€ 19,99

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Archive Les Poètes Maudits, - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Babylon, Frans, Brabantia Nostra, Frans Babylon

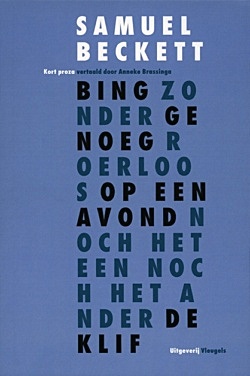

Samuel Beckett kreeg in 1969 de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur. De in deze uitgave opgenomen vertalingen van Anneke Brassinga zijn alle geschreven in het decennium rond dit jaartal.

Samuel Beckett kreeg in 1969 de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur. De in deze uitgave opgenomen vertalingen van Anneke Brassinga zijn alle geschreven in het decennium rond dit jaartal.

De teksten, die duidelijk minimalistisch van opzet zijn, kunnen het beste worden gesavoureerd met de stem – dus hardop gelezen. Daarbij komt de muzikale, repetitieve trant ten volle tot haar recht, evenals het poëtische aspect met veel assonantie en elliptische plastiek.

Beckett heeft al deze teksten nadrukkelijk gekarakteriseerd als verhalend proza, we kunnen er een soort bezweringen in horen van een bewustzijn dat aan zichzelf het eigen (voort)bestaan bewijst als een soort grensgebied tussen autonomie en ontlediging.

Samuel Beckett

Samuel Beckett (Dublin, 1906 – Parijs, 1989) was een Ierse (toneel) schrijver en dichter. Hij studeerde Frans, Italiaans en Engels in Dublin, reisde vervolgens door Europa om zich tenslotte permanent te vestigen in Parijs. Het merendeel van zijn werk schreef hij in het Frans, waarna hij het grotendeels ook weer zelf in het Engels vertaalde. Zijn teksten zijn vaak kaal, minimalistisch en diep pessimistisch over de menselijke natuur en de lotsbestemming van de mens. In 1969 ontving hij de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur.

Samuel Beckett

Kort proza

Vertaling: Anneke Brassinga

48 pagina’s

isbn 978 90 78627 33 3

Uitgeverij Vleugels, 2017

€ 20,85

# meer info website uitgeverij vleugels

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Samuel Beckett

Vera Rich

She smelt of time

walking slowly

like a mountain.

She railed

heavily

and flowed internally

and cared profoundly

but slowly,

at her own pace.

She smelt the energy

of her people,

of their language

on her lips.

Like a mother river

she carried many

with her on a raft

towards themselves.

01.03.10

Vincent Berquez

Vincent Berquez is a London–based artist and poet

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Berquez, Vincent, Vincent Berquez

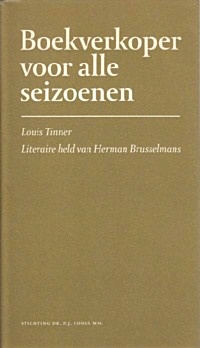

Boekverkoper voor alle seizoenen. Louis Tinner, literaire held van Herman Brusselmans.

Boekverkoper voor alle seizoenen. Louis Tinner, literaire held van Herman Brusselmans.

Uitgave bij gelegenheid van de manifestatie Boeken rond het paleis 2007.

Boekverkoper voor alle seizoenen is samengesteld door Jef van Kempen uit passages uit de Louis Tinner-romans van Herman Brusselmans.

Boekverkoper voor alle seizoenen

Louis Tinner,

literaire held van Herman Brusselmans

Samengesteld en ingeleid door Jef van Kempen

Boekverkoper voor alle seizoenen is samengesteld

uit passages uit de Louis Tinner-romans

van Herman Brusselmans.

Uitgeverij: Stichting Dr. P.J. Cools

Verschenen: 26 augustus 2007

Oplage: 500 exemplaren

Formaat: 24,5 x 14 cm.

Kartonnen platten met flappen.

Omvang: 32 blz.

ISBN: 978-90-806602-2-9

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Archive S-T, Herman Brusselmans, Jef van Kempen, Kempen, Jef van, Libraries in Literature

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature