Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

John Berger (London, November 5, 1926), art critic and author of Ways of Seeing, died in Paris (January 2, 2017)

John Berger (London, November 5, 1926), art critic and author of Ways of Seeing, died in Paris (January 2, 2017)

Berger’s best-known work was Ways of Seeing, a criticism of western cultural aesthetics. His novel G. won the Booker Prize. Half of the prize money Berger donated to the Black Panthers an radical African-American movement.

Berger began his career as a painter. But he also was a storyteller, novelist, essayist, screenwriter, dramatist and critic. He was one of the most internationally influential writers of the last fifty years.

His editor Tom Overton, who is writing John Berger’s biography, has said that the writer Berger “has let us know that art would enrich our lives”.

John Berger was author of: Another Way of Telling, About Looking, Photocopies, The Shape of a Pocket, And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief As Photos, Selected Essays of John Berger, Pig Earth, Once in Europa, King, Titian, Lilac and Flag, To the Wedding, Here Is Where We Meet, G., Pages of the Wound, Three Lives Of Lucie Cabrol.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, In Memoriam, John Berger

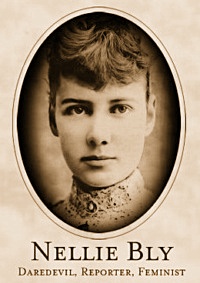

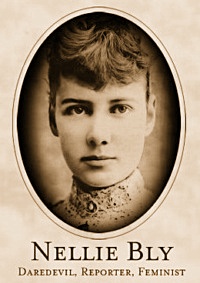

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter IV: Judge Duffy and the Police)

by Nellie Bly

But to return to my story. I kept up my role until the assistant matron, Mrs. Stanard, came in. She tried to persuade me to be calm. I began to see clearly that she wanted to get me out of the house at all hazards, quietly if possible. This I did not want. I refused to move, but kept up ever the refrain of my lost trunks. Finally some one suggested that an officer be sent for. After awhile Mrs. Stanard put on her bonnet and went out. Then I knew that I was making an advance toward the home of the insane. Soon she returned, bringing with her two policemen–big, strong men–who entered the room rather unceremoniously, evidently expecting to meet with a person violently crazy. The name of one of them was Tom Bockert.

When they entered I pretended not to see them. “I want you to take her quietly,” said Mrs. Stanard. “If she don’t come along quietly,” responded one of the men, “I will drag her through the streets.” I still took no notice of them, but certainly wished to avoid raising a scandal outside. Fortunately Mrs. Caine came to my rescue. She told the officers about my outcries for my lost trunks, and together they made up a plan to get me to go along with them quietly by telling me they would go with me to look for my lost effects. They asked me if I would go. I said I was afraid to go alone. Mrs. Stanard then said she would accompany me, and she arranged that the two policemen should follow us at a respectful

distance. She tied on my veil for me, and we left the house by the basement and started across town, the two officers following at some distance behind. We walked along very quietly and finally came to the station house, which the good woman assured me was the express office, and that there we should certainly find my missing effects. I went inside with fear and trembling, for good reason.

A few days previous to this I had met Captain McCullagh at a meeting held in Cooper Union. At that time I had asked him for some information which he had given me. If he were in, would he not recognize me? And then all would be lost so far as getting to the island was concerned. I pulled my sailor hat as low down over my face as I possibly could, and prepared for the ordeal. Sure enough there was sturdy Captain McCullagh standing near the desk.

He watched me closely as the officer at the desk conversed in a low tone with Mrs. Stanard and the policeman who brought me.

“Are you Nellie Brown?” asked the officer. I said I supposed I was. “Where do you come from?” he asked. I told him I did not know, and then Mrs. Stanard gave him a lot of information about me–told him how strangely I had acted at her home; how I had not slept a wink all night, and that in her opinion I was a poor unfortunate who had been driven crazy by inhuman treatment. There was some discussion between Mrs. Standard and the two officers, and Tom Bockert was told to take us down to the court in a car.

In the hands of the police.

“Come along,” Bockert said, “I will find your trunk for you.” We all went together, Mrs. Stanard, Tom Bockert, and myself. I said it was very kind of them to go with me, and I should not soon forget them. As we walked along I kept up my refrain about my trucks, injecting occasionally some remark about the dirty condition of the streets and the curious character of the people we met on the way. “I don’t think I have ever seen such people before,” I said. “Who are they?” I asked, and my companions looked upon me with expressions of pity, evidently believing I was a foreigner, an emigrant or something of the sort. They told me that the people around me were working people. I remarked once more that I thought there were too many working people in the world for the amount of work to be done, at which remark Policeman P. T. Bockert eyed me closely, evidently thinking that my mind was gone for good. We passed several other policemen, who generally asked my sturdy guardians what was the matter with me. By this time quite a number of ragged children were following us too, and they passed remarks about me that were to me original as well as amusing.

“What’s she up for?” “Say, kop, where did ye get her?” “Where did yer pull ‘er?”

“She’s a daisy!”

Poor Mrs. Stanard was more frightened than I was. The whole situation grew interesting, but I still had fears for my fate before the judge.

At last we came to a low building, and Tom Bockert kindly volunteered the information: “Here’s the express office. We shall soon find those trunks of yours.”

The entrance to the building was surrounded by a curious crowd and I did not think my case was bad enough to permit me passing them without some remark, so I asked if all those people had lost their trunks.

“Yes,” he said, “nearly all these people are looking for trunks.”

I said, “They all seem to be foreigners, too.” “Yes,” said Tom, “they are all foreigners just landed. They have all lost their trunks, and it takes most of our time to help find them for them.”

We entered the courtroom. It was the Essex Market Police Courtroom. At last the question of my sanity or insanity was to be decided. Judge Duffy sat behind the high desk, wearing a look which seemed to indicate that he was dealing out the milk of human kindness by wholesale. I rather feared I would not get the fate I sought, because of the kindness I saw on every line of his face, and it was with rather a sinking heart that I followed Mrs. Stanard as she answered the summons to go up to the desk, where Tom Bockert had just given an account of the affair.

“Come here,” said an officer. “What is your name?”

“Nellie Brown,” I replied, with a little accent. “I have lost my trunks, and would like if you could find them.”

“When did you come to New York?” he asked.

“I did not come to New York,” I replied (while I added, mentally, “because I have been here for some time.”)

“But you are in New York now,” said the man.

“No,” I said, looking as incredulous as I thought a crazy person could, “I did not come to New York.”

“That girl is from the west,” he said, in a tone that made me tremble. “She has a western accent.”

Some one else who had been listening to the brief dialogue here asserted that he had lived south and that my accent was southern, while another officer was positive it was eastern. I felt much relieved when the first spokesman turned to the judge and said:

“Judge, here is a peculiar case of a young woman who doesn’t know who she is or where she came from. You had better attend to it at once.”

I commenced to shake with more than the cold, and I looked around at the strange crowd about me, composed of poorly dressed men and women with stories printed on their faces of hard lives, abuse and poverty. Some were consulting eagerly with friends, while others sat still with a look of utter hopelessness. Everywhere was a sprinkling of well-dressed, well-fed officers watching the scene passively and almost indifferently. It was only an old story with them. One more unfortunate added to a long list which had long since ceased to be of any interest or concern to them.

Nellie before Judge Duffy.

“Come here, girl, and lift your veil,” called out Judge Duffy, in tones which surprised me by a harshness which I did not think from the kindly face he possessed.

“Who are you speaking to?” I inquired, in my stateliest manner.

“Come here, my dear, and lift your veil. You know the Queen of England, if she were here, would have to lift her veil,” he said, very kindly.

“That is much better,” I replied. “I am not the Queen of England, but I’ll lift my veil.”

As I did so the little judge looked at me, and then, in a very kind and gentle tone, he said:

“My dear child, what is wrong?”

“Nothing is wrong except that I have lost my trunks, and this man,” indicating Policeman Bockert, “promised to bring me where they could be found.”

“What do you know about this child?” asked the judge, sternly, of Mrs. Stanard, who stood, pale and trembling, by my side.

“I know nothing of her except that she came to the home yesterday and asked to remain overnight.”

“The home! What do you mean by the home?” asked Judge Duffy, quickly.

“It is a temporary home kept for working women at No. 84 Second Avenue.”

“What is your position there?”

“I am assistant matron.”

“Well, tell us all you know of the case.”

“When I was going into the home yesterday I noticed her coming down the avenue. She was all alone. I had just got into the house when the bell rang and she came in. When I talked with her she wanted to know if she could stay all night, and I said she could. After awhile she said all the people in the house looked crazy, and she was afraid of them. Then she would not go to bed, but sat up all the night.”

“Had she any money?”

“Yes,” I replied, answering for her, “I paid her for everything, and the eating was the worst I ever tried.”

There was a general smile at this, and some murmurs of “She’s not so crazy on the food question.”

“Poor child,” said Judge Duffy, “she is well dressed, and a lady. Her English is perfect, and I would stake everything on her being a good girl. I am positive she is somebody’s darling.”

At this announcement everybody laughed, and I put my handkerchief over my face and endeavored to choke the laughter that threatened to spoil my plans, in despite of my resolutions.

“I mean she is some woman’s darling,” hastily amended the judge. “I am sure some one is searching for her. Poor girl, I will be good to her, for she looks like my sister, who is dead.”

There was a hush for a moment after this announcement, and the officers glanced at me more kindly, while I silently blessed the kind-hearted judge, and hoped that any poor creatures who might be afflicted as I pretended to be should have as kindly a man to deal with as Judge Duffy.

“I wish the reporters were here,” he said at last. “They would be able to find out something about her.”

I got very much frightened at this, for if there is any one who can ferret out a mystery it is a reporter. I felt that I would rather face a mass of expert doctors, policemen, and detectives than two bright specimens of my craft, so I said:

“I don’t see why all this is needed to help me find my trunks. These men are impudent, and I do not want to be stared at. I will go away. I don’t want to stay here.”

So saying, I pulled down my veil and secretly hoped the reporters would be detained elsewhere until I was sent to the asylum.

“I don’t know what to do with the poor child,” said the worried judge. “She must be taken care of.”

“Send her to the Island,” suggested one of the officers.

“Oh, don’t!” said Mrs. Stanard, in evident alarm. “Don’t! She is a lady and it would kill her to be put on the Island.”

For once I felt like shaking the good woman. To think the Island was just the place I wanted to reach and here she was trying to keep me from going there! It was very kind of her, but rather provoking under the circumstances.

“There has been some foul work here,” said the judge. “I believe this child has been drugged and brought to this city. Make out the papers and we will send her to Bellevue for examination. Probably in a few days the effect of the drug will pass off and she will be able to tell us a story that will be startling. If the reporters would only come!”

I dreaded them, so I said something about not wishing to stay there any longer to be gazed at. Judge Duffy then told Policeman Bockert to take me to the back office. After we were seated there Judge Duffy came in and asked me if my home was in Cuba.

“Yes,” I replied, with a smile. “How did you know?”

“Oh, I knew it, my dear. Now, tell me were was it? In what part of Cuba?”

“On the hacienda,” I replied.

“Ah,” said the judge, “on a farm. Do you remember Havana?”

“Si, senor,” I answered; “it is near home. How did you know?”

“Oh, I knew all about it. Now, won’t you tell me the name of your home?” he asked, persuasively.

“That’s what I forget,” I answered, sadly. “I have a headache all the time, and it makes me forget things. I don’t want them to trouble me. Everybody is asking me questions, and it makes my head worse,” and in truth it did.

“Well, no one shall trouble you any more. Sit down here and rest awhile,” and the genial judge left me alone with Mrs. Stanard.

Just then an officer came in with a reporter. I was so frightened, and thought I would be recognized as a journalist, so I turned my head away and said, “I don’t want to see any reporters; I will not see any; the judge said I was not to be troubled.”

“Well, there is no insanity in that,” said the man who had brought the reporter, and together they left the room. Once again I had a fit of fear. Had I gone too far in not wanting to see a reporter, and was my sanity detected? If I had given the impression that I was sane, I was determined to undo it, so I jumped up and ran back and forward through the office, Mrs. Stanard clinging terrified to my arm.

“I won’t stay here; I want my trunks! Why do they bother me with so many people?” and thus I kept on until the ambulance surgeon came in, accompanied by the judge.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter IV: Judge Duffy and the Police)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

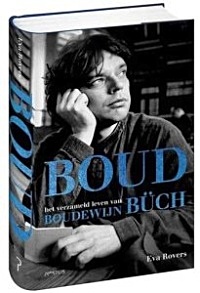

Eva Rovers: Boud

Het verzameld leven van Boudewijn Büch

Eva Rovers schreef eerder de veelgeprezen biografie van kunstverzamelaar Helene Kröller-Müller, De eeuwigheid verzameld. Hiervoor ontving zij onder meer de Erik Hazelhoff Roelfzema Biografieprijs.

Goethe, Mick Jagger, eilanden, dodo’s en eeuwenoude boeken: Boudewijn Büch liet Nederland kennismaken met de meest uiteenlopende onderwerpen en wist met zijn aanstekelijke enthousiasme literatuur en geschiedenis even toegankelijk te maken als popmuziek. Als kind had hij al ontdekt dat hij met verhalen in staat was het leven naar zijn hand te zetten. Uit atlassen, poëzie en rock & roll bouwde hij een eigen wereld op en sleurde daarin iedereen mee met wie hij sprak. Dat bezorgde hem invloedrijke vrienden, toegang tot de literaire wereld en heel veel aandacht. Maar zijn betoverende verhalen brachten hem ook talrijke demonen, die hij zijn leven lang moest bevechten.

Goethe, Mick Jagger, eilanden, dodo’s en eeuwenoude boeken: Boudewijn Büch liet Nederland kennismaken met de meest uiteenlopende onderwerpen en wist met zijn aanstekelijke enthousiasme literatuur en geschiedenis even toegankelijk te maken als popmuziek. Als kind had hij al ontdekt dat hij met verhalen in staat was het leven naar zijn hand te zetten. Uit atlassen, poëzie en rock & roll bouwde hij een eigen wereld op en sleurde daarin iedereen mee met wie hij sprak. Dat bezorgde hem invloedrijke vrienden, toegang tot de literaire wereld en heel veel aandacht. Maar zijn betoverende verhalen brachten hem ook talrijke demonen, die hij zijn leven lang moest bevechten.

Eva Rovers kreeg exclusief inzage in Boudewijn Büchs persoonlijke archief, met dozen vol brieven, foto’s en dagboeken. Daarmee begon een reis door een leven dat even onwaarschijnlijk als fantastisch was; een leven dat Büch transformeerde tot een literair spel met feit en fictie, dat hij tot de uiterste consequentie doorvoerde en dat jaren na zijn dood culmineerde in een grande finale.

Na het overlijden van Boudewijn Büch in 2002 is in talloze boeken, krantenartikelen, opiniestukken, interviews en televisieprogramma’s geprobeerd het leven van dit fenomeen te vangen. Verreweg de meeste aandacht ging uit naar Boudewijn Büch de mystificateur, de man die aan de werkelijkheid niet genoeg had en daarom een parallel universum schiep.

Na zijn dood was er nauwelijks aandacht voor de rol die Büch de voorgaande twee decennia had gespeeld binnen de culturele wereld. Door het literaire establishment werd hij weggezet als straatschoffie dat ook eens een boek had gelezen. Deze biografie laat zien dat Büch meer was dan een fantast. Hij was iemand die een breed en jong publiek wist te interesseren voor onderwerpen die op het eerste gezicht weinig sexy lijken. Op aanstekelijke wijze liet hij zien dat een mens geen stoffige professor hoeft te zijn om van geschiedenis of poëzie te houden. Hij was een culturele alleseter, die zijn loopbaan als dichter begon en als televisiepersoonlijkheid eindigde. In de tussenliggende jaren werkte hij met evenveel plezier aan columns voor Penthouse en Nieuwe Revu als voor NRC Handelsblad. Hij beschreef de wereldliteratuur in het literaire tijdschrift Maatstaf om vervolgens in het VARA-programma Büch de nieuwste publicaties door de studio te smijten als deze hem niet bevielen. Dankzij deze veelzijdigheid en het scala aan podia waarmee Büch zijn voorkeuren wereldkundig maakte, wist hij bij een breed publiek de interesse voor literatuur, geschiedenis en poëzie nieuw leven in te blazen.

‘Voor Büch waren leven en literatuur onderdeel van dezelfde caleidoscopische verzameling, waar hij naar hartenlust facetten aan toevoegde zodat er telkens nieuwe verbindingen ontstonden. Zijn brieven en dagboeken waren onlosmakelijk verbonden met de interviews die hij gaf, de boeken die hij schreef en de programma’s die hij maakte. Met ieder boek, ieder gedicht, ieder interview en met iedere column, brief en dagboekpassage lijkt hij gewerkt te hebben aan zijn eigen totaaltheater: de Comédie Büchienne.’

Eva Rovers

Boud

Het verzameld leven van Boudewijn Büch

Omvang 608 p.

Gebonden

Druk 1 verschenen op 11-11-16

Uitgeverij Prometheus

isbn 9789035137424

€ 29,90

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Boudewijn Büch

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter III: In the temporary home)

by Nellie Bly

I was left to begin my career as Nellie Brown, the insane girl. As I walked down the avenue I tried to assume the look which maidens wear in pictures entitled “Dreaming.” “Far-away” expressions have a crazy air. I passed through the little paved yard to the entrance of the Home. I pulled the bell, which sounded loud enough for a church chime, and nervously awaited the opening of the door to the Home, which I intended should ere long cast me forth and out upon the charity of the police. The door was thrown back with a vengeance, and a short, yellow-haired girl of some thirteen summers stood before me.

“Is the matron in?” I asked, faintly.

“Yes, she’s in; she’s busy. Go to the back parlor,” answered the girl, in a loud voice, without one change in her peculiarly matured face.

At the temporary home for women.

I followed these not overkind or polite instructions and found myself in a dark, uncomfortable back-parlor. There I awaited the arrival of my hostess. I had been seated some twenty minutes at the least, when a slender woman, clad in a plain, dark dress entered and, stopping before me, ejaculated inquiringly, “Well?”

“Are you the matron?” I asked.

“No,” she replied, “the matron is sick; I am her assistant. What do you want?”

“I want to stay here for a few days, if you can accommodate me.”

“Well, I have no single rooms, we are so crowded; but if you will occupy a room with another girl, I shall do that much for you.”

“I shall be glad of that,” I answered. “How much do you charge?” I had brought only about seventy cents along with me, knowing full well that the sooner my funds were exhausted the sooner I should be put out, and to be put out was what I was working for.

“We charge thirty cents a night,” was her reply to my question, and with that I paid her for one night’s lodging, and she left me on the plea of having something else to look after. Left to amuse myself as best I could, I took a survey of my surroundings.

They were not cheerful, to say the least. A wardrobe, desk, book-case, organ, and several chairs completed the furnishment of the room, into which the daylight barely came.

By the time I had become familiar with my quarters a bell, which rivaled the door-bell in its loudness, began clanging in the basement, and simultaneously

women went trooping down-stairs from all parts of the house. I imagined, from the obvious signs, that dinner was served, but as no one had said anything to me I made no effort to follow in the hungry train. Yet I did wish that some one would invite me down. It always produces such a lonely, homesick feeling to know others are eating, and we haven’t a chance, even if we are not hungry. I was glad when the assistant matron came up and asked me if I did not want something to eat. I replied that I did, and then I asked her what her name was. Mrs. Stanard, she said, and I immediately wrote it down in a notebook I had taken with me for the purpose of making memoranda, and in which I had written several pages of utter nonsense for inquisitive scientists.

Thus equipped I awaited developments. But my dinner–well, I followed Mrs. Stanard down the uncarpeted stairs into the basement; where a large number of women were eating. She found room for me at a table with three other women. The short-haired slavey who had opened the door now put in an appearance as waiter. Placing her arms akimbo and staring me out of countenance she said:

“Boiled mutton, boiled beef, beans, potatoes, coffee or tea?”

“Beef, potatoes, coffee and bread,” I responded.

“Bread goes in,” she explained, as she made her way to the kitchen, which was in the rear. It was not very long before she returned with what I had ordered on a large, badly battered tray, which she banged down before me. I began my simple meal. It was not very enticing, so while making a feint of eating I watched the others.

I have often moralized on the repulsive form charity always assumes! Here was a home for deserving women and yet what a mockery the name was. The floor was bare, and the little wooden tables were sublimely ignorant of such modern beautifiers as varnish, polish and table-covers. It is useless to talk about the cheapness of linen and its effect on civilization. Yet these honest workers, the most deserving of women, are asked to call this spot of bareness–home.

I have often moralized on the repulsive form charity always assumes! Here was a home for deserving women and yet what a mockery the name was. The floor was bare, and the little wooden tables were sublimely ignorant of such modern beautifiers as varnish, polish and table-covers. It is useless to talk about the cheapness of linen and its effect on civilization. Yet these honest workers, the most deserving of women, are asked to call this spot of bareness–home.

When the meal was finished each woman went to the desk in the corner, where Mrs. Stanard sat, and paid her bill. I was given a much-used, and abused, red check, by the original piece of humanity in shape of my waitress. My bill was about thirty cents.

After dinner I went up-stairs and resumed my former place in the back parlor. I was quite cold and uncomfortable, and had fully made up my mind that I could not endure that sort of business long, so the sooner I assumed my insane points the sooner I would be released from enforced idleness. Ah! that was indeed the longest day I had ever lived. I listlessly watched the women in the front parlor, where all sat except myself.

One did nothing but read and scratch her head and occasionally call out mildly, “Georgie,” without lifting her eyes from her book. “Georgie” was her over-frisky boy, who had more noise in him than any child I ever saw before. He did everything that was rude and unmannerly, I thought, and the mother never said a word unless she heard some one else yell at him. Another woman always kept going to sleep and waking herself up with her own snoring. I really felt wickedly thankful it was only herself she awakened. The majority of the women sat there doing nothing, but there were a few who made lace and knitted unceasingly. The enormous door-bell seemed to be going all the time, and so did the short-haired girl. The latter was, besides, one of those girls who sing all the time snatches of all the songs and hymns that have been composed for the last fifty years. There is such a thing as martyrdom in these days. The ringing of the bell brought more people who wanted shelter for the night. Excepting one woman, who was from the country on a day’s shopping expedition, they were working women, some of them with children.

As it drew toward evening Mrs. Stanard came to me and said:

“What is wrong with you? Have you some sorrow or trouble?”

“No,” I said, almost stunned at the suggestion. “Why?”

“Oh, because,” she said, womanlike, “I can see it in your face. It tells the story of a great trouble.”

“Yes, everything is so sad,” I said, in a haphazard way, which I had intended to reflect my craziness.

“But you must not allow that to worry you. We all have our troubles, but we get over them in good time. What kind of work are you trying to get?”

“I do not know; it’s all so sad,” I replied.

“Would you like to be a nurse for children and wear a nice white cap and apron?” she asked.

I put my handkerchief up to my face to hide a smile, and replied in a muffled tone, “I never worked; I don’t know how.”

“But you must learn,” she urged; “all these women here work.”

“Do they?” I said, in a low, thrilling whisper. “Why, they look horrible to me; just like crazy women. I am so afraid of them.”

“They don’t look very nice,” she answered, assentingly, “but they are good, honest working women. We do not keep crazy people here.”

I again used my handkerchief to hide a smile, as I thought that before morning she would at least think she had one crazy person among her flock.

“They all look crazy,” I asserted again, “and I am afraid of them. There are so many crazy people about, and one can never tell what they will do. Then there

are so many murders committed, and the police never catch the murderers,” and I finished with a sob that would have broken up an audience of blase critics. She gave a sudden and convulsive start, and I knew my first stroke had gone home. It was amusing to see what a remarkably short time it took her to get up from her chair and to whisper hurriedly: “I’ll come back to talk with you after a while.” I knew she would not come back and she did not.

When the supper-bell rang I went along with the others to the basement and partook of the evening meal, which was similar to dinner, except that there was

a smaller bill of fare and more people, the women who are employed outside during the day having returned. After the evening meal we all adjourned to the parlors, where all sat, or stood, as there were not chairs enough to go round.

It was a wretchedly lonely evening, and the light which fell from the solitary gas jet in the parlor, and oil-lamp the hall, helped to envelop us in a dusky

hue and dye our spirits navy blue. I felt it would not require many inundations of this atmosphere to make me a fit subject for the place I was striving to

reach.

I watched two women, who seemed of all the crowd to be the most sociable, and I selected them as the ones to work out my salvation, or, more properly speaking, my condemnation and conviction. Excusing myself and saying that I felt lonely, I asked if I might join their company. They graciously consented, so with my hat and gloves on, which no one had asked me to lay aside, I sat down and listened to the rather wearisome conversation, in which I took no part, merely keeping up my sad look, saying “Yes,” or “No,” or “I can’t say,” to their observations. Several times I told them I thought everybody in the house looked crazy, but they were slow to catch on to my very original remark. One said her name was Mrs. King and that she was a Southern woman. Then she said that I had a Southern accent. She asked me bluntly if I did not really come from the South. I said “Yes.” The other woman got to talking about the Boston boats and asked me if I knew at what time they left.

For a moment I forgot my role of assumed insanity, and told her the correct hour of departure. She then asked me what work I was going to do, or if I had ever done any. I replied that I thought it very sad that there were so many working people in the world. She said in reply that she had been unfortunate and had come to New York, where she had worked at correcting proofs on a medical dictionary for some time, but that her health had given way under the task, and that she was now going to Boston again. When the maid came to tell us to go to bed I remarked that I was afraid, and again ventured the assertion that all the women in the house seemed to be crazy. The nurse insisted on my going to bed. I asked if I could not sit on the stairs, but she said, decisively: “No; for every one in the house would think you were crazy.” Finally I allowed them to take me to a room.

Here I must introduce a new personage by name into my narrative. It is the woman who had been a proofreader, and was about to return to Boston. She was a Mrs. Caine, who was as courageous as she was good-hearted. She came into my room, and sat and talked with me a long time, taking down my hair with gentle ways. She tried to persuade me to undress and go to bed, but I stubbornly refused to do so. During this time a number of the inmates of the house had gathered around us. They expressed themselves in various ways. “Poor loon!” they said. “Why, she’s crazy enough!” “I am afraid to stay with such a crazy being in house.” “She will murder us all before morning.” One woman was for sending for a policeman to take me at once. They were all in a terrible and real state of fright.

No one wanted to be responsible for me, and the woman who was to occupy the room with me declared that she would not stay with that “crazy woman” for all the money of the Vanderbilts. It was then that Mrs. Caine said she would stay with me. I told her I would like to have her do so. So she was left with me. She didn’t undress, but lay down on the bed, watchful of my movements. She tried to induce me to lie down, but I was afraid to do this. I knew that if I once gave way I should fall asleep and dream as pleasantly and peacefully as a child. I should, to use a slang expression, be liable to “give myself dead away.” So I insisted on sitting on the side of the bed and staring blankly at vacancy. My poor companion was put into a wretched state of unhappiness. Every few moments she would rise up to look at me. She told me that my eyes shone terribly brightly and then began to question me, asking me where I had lived, how long I had been in New York, what I had been doing, and many things besides. To all her questionings I had but one response–I told her that I had forgotten everything, that ever since my headache had come on I could not remember.

Poor soul! How cruelly I tortured her, and what a kind heart she had! But how I tortured all of them! One of them dreamed of me–as a nightmare. After I had been in the room an hour or so, I was myself startled by hearing a woman screaming in the next room. I began to imagine that I was really in an insane asylum.

Mrs. Caine woke up, looked around, frightened, and listened. She then went out and into the next room, and I heard her asking another woman some questions. When she came back she told me that the woman had had a hideous nightmare. She had been dreaming of me. She had seen me, she said, rushing at her with a knife in my hand, with the intention of killing her. In trying to escape me she had fortunately been able to scream, and so to awaken herself and scare off her nightmare. Then Mrs. Caine got into bed again, considerably agitated, but very sleepy.

Mrs. Caine woke up, looked around, frightened, and listened. She then went out and into the next room, and I heard her asking another woman some questions. When she came back she told me that the woman had had a hideous nightmare. She had been dreaming of me. She had seen me, she said, rushing at her with a knife in my hand, with the intention of killing her. In trying to escape me she had fortunately been able to scream, and so to awaken herself and scare off her nightmare. Then Mrs. Caine got into bed again, considerably agitated, but very sleepy.

I was weary, too, but I had braced myself up to the work, and was determined to keep awake all night so as to carry on my work of impersonation to a successful end in the morning. I heard midnight. I had yet six hours to wait for daylight. The time passed with excruciating slowness. Minutes appeared hours. The noises in the house and on the avenue ceased.

Fearing that sleep would coax me into its grasp, I commenced to review my life. How strange it all seems! One incident, if never so trifling, is but a link more to chain us to our unchangeable fate. I began at the beginning, and lived again the story of my life. Old friends were recalled with a pleasurable thrill; old enmities, old heartaches, old joys were once again present. The turned-down pages of my life were turned up, and the past was present.

When it was completed, I turned my thoughts bravely to the future, wondering, first, what the next day would bring forth, then making plans for the carrying out of my project. I wondered if I should be able to pass over the river to the goal of my strange ambition, to become eventually an inmate of the halls inhabited by my mentally wrecked sisters. And then, once in, what would be my experience? And after? How to get out? Bah! I said, they will get me out.

That was the greatest night of my existence. For a few hours I stood face to face with “self!”

I looked out toward the window and hailed with joy the slight shimmer of dawn. The light grew strong and gray, but the silence was strikingly still. My

companion slept. I had still an hour or two to pass over. Fortunately I found some employment for my mental activity. Robert Bruce in his captivity had won confidence in the future, and passed his time as pleasantly as possible under the circumstances, by watching the celebrated spider building his web. I had less noble vermin to interest me. Yet I believe I made some valuable discoveries in natural history. I was about to drop off to sleep in spite of myself when I was suddenly startled to wakefulness. I thought I heard something crawl and fall down upon the counterpane with an almost inaudible thud.

I had the opportunity of studying these interesting animals very thoroughly. They had evidently come for breakfast, and were not a little disappointed to

find that their principal plat was not there. They scampered up and down the pillow, came together, seemed to hold interesting converse, and acted in every way as if they were puzzled by the absence of an appetizing breakfast. After one consultation of some length they finally disappeared, seeking victims elsewhere, and leaving me to pass the long minutes by giving my attention to cockroaches, whose size and agility were something of a surprise to me.

My room companion had been sound asleep for a long time, but she now woke up, and expressed surprise at seeing me still awake and apparently as lively as a cricket. She was as sympathetic as ever. She came to me and took my hands and tried her best to console me, and asked me if I did not want to go home. She kept me up-stairs until nearly everybody was out of the house, and then took me down to the basement for coffee and a bun. After that, partaken in silence, I went back to my room, where I sat down, moping. Mrs. Caine grew more and more anxious. “What is to be done?” she kept exclaiming. “Where are your friends?” “No,” I answered, “I have no friends, but I have some trunks. Where are they? I want them.” The good woman tried to pacify me, saying that they would be found in good time. She believed that I was insane.

Yet I forgive her. It is only after one is in trouble that one realizes how little sympathy and kindness there are in the world. The women in the Home who

were not afraid of me had wanted to have some amusement at my expense, and so they had bothered me with questions and remarks that had I been insane would have been cruel and inhumane. Only this one woman among the crowd, pretty and delicate Mrs. Caine, displayed true womanly feeling. She compelled the others to cease teasing me and took the bed of the woman who refused to sleep near me. She protested against the suggestion to leave me alone and to have me locked up for the night so that I could harm no one. She insisted on remaining with me in order to administer aid should I need it. She smoothed my hair and bathed my brow and talked as soothingly to me as a mother would do to an ailing child. By every means she tried to have me go to bed and rest, and when it drew toward morning she got up and wrapped a blanket around me for fear I might get cold; then she kissed me on the brow and whispered, compassionately:

“Poor child, poor child!”

How much I admired that little woman’s courage and kindness. How I longed to reassure her and whisper that I was not insane, and how I hoped that, if any poor girl should ever be so unfortunate as to be what I was pretending to be, she might meet with one who possessed the same spirit of human kindness possessed by Mrs. Ruth Caine.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter III: In the temporary home)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter II: Preparing for the ordeal)

by Nellie Bly

BUT to return to my work and my mission. After receiving my instructions I returned to my boarding-house, and when evening came I began to practice the role in which I was to make my debut on the morrow. What a difficult task, I thought, to appear before a crowd of people and convince them that I was insane. I had never been near insane persons before in my life, and had not the faintest idea of what their actions were like. And then to be examined by a number of learned physicians who make insanity a specialty, and who daily come in contact with insane people! How could I hope to pass these doctors and convince them that I was crazy? I feared that they could not be deceived. I began to think my task a hopeless one; but it had to be done. So I flew to the mirror and examined my face. I remembered all I had read of the doings of crazy people, how first of all they have staring eyes, and so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinkingly at my own reflection. I assure you the sight was not reassuring, even to myself, especially in the dead of night. I tried to turn the gas up higher in hopes that it would raise my courage. I succeeded only partially, but I consoled myself with the thought that in a few nights more I would not be there, but locked up in a cell with a lot of lunatics.

The weather was not cold; but, nevertheless, when I thought of what was to come, wintery chills ran races up and down my back in very mockery of the perspiration which was slowly but surely taking the curl out of my bangs. Between times, practicing before the mirror and picturing my future as a lunatic, I read snatches of improbable and impossible ghost stories, so that when the dawn came to chase away the night, I felt that I was in a fit mood for my mission, yet hungry enough to feel keenly that I wanted my breakfast. Slowly and sadly I took my morning bath and quietly bade farewell to a few of the most precious articles known to modern civilization. Tenderly I put my tooth-brush aside, and, when taking a final rub of the soap, I murmured, “It may be for days, and it may be–for longer.” Then I donned the old clothing I had selected for the occasion.

I was in the mood to look at everything through very serious glasses. It’s just as well to take a last “fond look,” I mused, for who could tell but that the strain of playing crazy, and being shut up with a crowd of mad people, might turn my own brain, and I would never get back. But not once did I think of shirking my mission. Calmly, outwardly at least, I went out to my crazy business.

I first thought it best to go to a boarding-house, and, after securing lodging, confidentially tell the landlady, or lord, whichever it might chance to be, that I was seeking work, and, in a few days after, apparently go insane. When I reconsidered the idea, I feared it would take too long to mature. Suddenly I thought how much easier it would be to go to a boarding-home for working women. I knew, if once I made a houseful of women believe me crazy, that they would never rest until I was out of their reach and in secure quarters.

From a directory I selected the Temporary Home for Females, No. 84 Second Avenue. As I walked down the avenue, I determined that, once inside the Home, I should do the best I could to get started on my journey to Blackwell’s Island and the Insane Asylum.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter II: Preparing for the ordeal)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

NEW YORK: IAN L. MUNRO, PUBLISHER, 24 AND 26 VANDEWATER STREET

NEW YORK: IAN L. MUNRO, PUBLISHER, 24 AND 26 VANDEWATER STREET

WHY ARE THE MADAME MORA’S CORSETS A MARVEL OF COMFORT AND ELEGANCE!?!

Try them and you will Find

WHY they need no breaking in, but feel easy at once.

WHY they are liked by Ladies of full figure.

WHY they do not break down over the hips, and

WHY the celebrated French curved band prevents any wrinkling or stretching at the sides.

WHY dressmakers delight in fitting dresses over them.

WHY merchants say they give better satisfaction than any others.

WHY they take pains to recommend them.

Their popularity has induced many imitations, which are frauds, high at any price. Buy only the genuine, stamped Madame Mora’s. Sold by all leading dealers with this GUARANTEE: that if not perfectly satisfactory upon trial the money will be refunded.

L. KRAUS & CO., Manufacturers, Birmingham, Conn.

INTRODUCTION

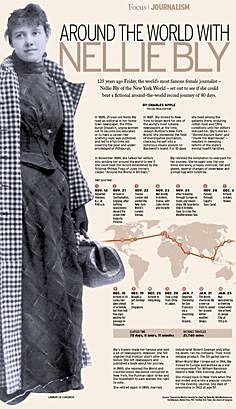

SINCE my experiences in Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum were published in the World I have received hundreds of letters in regard to it. The edition containing my story long since ran out, and I have been prevailed upon to allow it to be published in book form, to satisfy the hundreds who are yet asking for copies.

I am happy to be able to state as a result of my visit to the asylum and the exposures consequent thereon, that the City of New York has appropriated $1,000,000 more per annum than ever before for the care of the insane. So I have at least the satisfaction of knowing that the poor unfortunates will be the better cared for because of my work.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter 1: A delicate mission)

by Nellie Bly

On the 22d of September I was asked by the World if I could have myself committed to one of the asylums for the insane in New York, with a view to writing a plain and unvarnished narrative of the treatment of the patients therein and the methods of management, etc. Did I think I had the courage to go through such an ordeal as the mission would demand? Could I assume the characteristics of insanity to such a degree that I could pass the doctors, live for a week among the insane without the authorities there finding out that I was only a “chiel amang ’em takin’ notes?” I said I believed I could. I had some faith in my own ability as an actress and thought I could assume insanity long enough to accomplish any mission intrusted to me. Could I pass a week in the insane ward at Blackwell’s Island? I said I could and I would. And I did.

My instructions were simply to go on with my work as soon as I felt that I was ready. I was to chronicle faithfully the experiences I underwent, and when once within the walls of the asylum to find out and describe its inside workings, which are always, so effectually hidden by white-capped nurses, as well as by bolts and bars, from the knowledge of the public. “We do not ask you to go there for the purpose of making sensational revelations. Write up things as you find them, good or bad; give praise or blame as you think best, and the truth all the time. But I am afraid of that chronic smile of yours,” said the editor. “I will smile no more,” I said, and I went away to execute my delicate and, as I found out, difficult mission.

My instructions were simply to go on with my work as soon as I felt that I was ready. I was to chronicle faithfully the experiences I underwent, and when once within the walls of the asylum to find out and describe its inside workings, which are always, so effectually hidden by white-capped nurses, as well as by bolts and bars, from the knowledge of the public. “We do not ask you to go there for the purpose of making sensational revelations. Write up things as you find them, good or bad; give praise or blame as you think best, and the truth all the time. But I am afraid of that chronic smile of yours,” said the editor. “I will smile no more,” I said, and I went away to execute my delicate and, as I found out, difficult mission.

If I did get into the asylum, which I hardly hoped to do, I had no idea that my experiences would contain aught else than a simple tale of life in an asylum.

That such an institution could be mismanaged, and that cruelties could exist ‘neath its roof, I did not deem possible. I always had a desire to know asylum

life more thoroughly–a desire to be convinced that the most helpless of God’s creatures, the insane, were cared for kindly and properly. The many stories I

had read of abuses in such institutions I had regarded as wildly exaggerated or else romances, yet there was a latent desire to know positively.

I shuddered to think how completely the insane were in the power of their keepers, and how one could weep and plead for release, and all of no avail, if

the keepers were so minded. Eagerly I accepted the mission to learn the inside workings of the Blackwell Island Insane Asylum.

“How will you get me out,” I asked my editor, “after I once get in?”

“I do not know,” he replied, “but we will get you out if we have to tell who you are, and for what purpose you feigned insanity–only get in.”

I had little belief in my ability to deceive the insanity experts, and I think my editor had less.

All the preliminary preparations for my ordeal were left to be planned by myself. Only one thing was decided upon, namely, that I should pass under the pseudonym of Nellie Brown, the initials of which would agree with my own name and my linen, so that there would be no difficulty in keeping track of my

movements and assisting me out of any difficulties or dangers I might get into.

There were ways of getting into the insane ward, but I did not know them. I might adopt one of two courses. Either I could feign insanity at the house of friends, and get myself committed on the decision of two competent physicians, or I could go to my goal by way of the police courts.

Nellie practices insanity at home

On reflection I thought it wiser not to inflict myself upon my friends or to get any good-natured doctors to assist me in my purpose. Besides, to get to Blackwell’s Island my friends would have had to feign poverty, and, unfortunately for the end I had in view, my acquaintance with the struggling poor, except my own self, was only very superficial. So I determined upon the plan which led me to the successful accomplishment of my mission. I succeeded in getting committed to the insane ward at Blackwell’s Island, where I spent ten days and nights and had an experience which I shall never forget. I took upon myself to enact the part of a poor, unfortunate crazy girl, and felt it my duty not to shirk any of the disagreeable results that should follow. I became one of the city’s insane wards for that length of time, experienced much, and saw and heard more of the treatment accorded to this helpless class of our population, and when I had seen and heard enough, my release was promptly secured. I left the insane ward with pleasure and regret–pleasure that I was once more able to enjoy the free breath of heaven; regret that I could not have brought with me some of the unfortunate women who lived and suffered with me, and who, I am convinced, are just as sane as I was and am now myself.

But here let me say one thing: From the moment I entered the insane ward on the Island, I made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity. I talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted the crazier I was thought to be by all except one physician, whose kindness and gentle ways I shall not soon forget.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter 1: A delicate mission)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

Katharine Lee Bates

(1859-1929)

The Great Twin Brethren

The battle will not cease

Till once again on those white steeds ye ride,

O heaven-descended Twins,

Before humanity’s bewildered host.

Our javelins

Fly wide,

And idle is our cannon’s boast.

Lead us, triumphant Brethren, Love and Peace.

A fairer Golden Fleece

Our more adventurous Argo fain would seek,

But save, O Sons of Jove,

Your blended light go with us, vain employ

It were to rove

This bleak,

Blind waste. To unimagined joy

Guide us, immortal Brethren, Love and Peace.

Katharine Lee Bates poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, CLASSIC POETRY

Ingrid Jonker – André Brink

Ingrid Jonker – André Brink

Vlam in de sneeuw

Van de jonggestorven, iconische dichter Ingrid Jonker is bekend dat ze mannen het hoofd op hol wist te brengen. Een van hen was de onlangs gestorven schrijver André Brink. Tot kort voor Ingrids zelfgekozen dood, op haar eenendertigste, was hij haar vurige minnaar. Op geografische afstand, wat voor de literatuurgeschiedenis nu een zegen blijkt. Want het noodde hen tot een jarenlange, ongekend intense liefdescorrespondentie. Vlam in de sneeuw biedt allereerst een intieme blik op de jonge levens van twee veelbelovende schrijvers die, nog zoekende naar hun plek in de wereld, tot over hun oren verliefd op elkaar worden. Maar ze delen niet alleen hun liefde voor elkaar, ook delen ze hun twijfels over hun schrijverschap en hun diepste overtuigingen over geloof, literatuur en politiek. Het is met grote trots dat wij deze tot vurige woorden gestolde passie, kort na verschijning in Zuid-Afrika, nu voor de Nederlandse lezer mogen ontsluiten.

512 pagina’s

omslag: Studio Ron van Roon

ISBN: 978 90 5759 775 6

Nur: 320

originele titel: Vlam in die sneeu

vertaler: Karina van Santen, Rob van der Veer en Martine Vosmaer

€ 34,90

uitgeverij Podium

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Archive S.A. literature, - Book News, André Brink, Archive A-B, Archive I-J, Ingrid Jonker, Ingrid Jonker

In juni en juli 2016 speelt Toneelgroep De Appel de Decamerone (1353) van Giovanni Boccaccio. De Decamerone is een verzameling van honderd verhalen over liefde, list, lust en bedrog. In 2013 bracht Arie de Mol een aantal van deze prachtige verhalen tot leven in een Limburgse kasteelhoeve. Erik-Ward Geerlings schreef voor deze succesvoorstelling een eigen speelse bewerking van Boccaccio’s meesterwerk. Dit voorjaar zet Arie de Mol, nu samen met de spelers van De Appel, zijn tanden opnieuw in deze tekst.

In juni en juli 2016 speelt Toneelgroep De Appel de Decamerone (1353) van Giovanni Boccaccio. De Decamerone is een verzameling van honderd verhalen over liefde, list, lust en bedrog. In 2013 bracht Arie de Mol een aantal van deze prachtige verhalen tot leven in een Limburgse kasteelhoeve. Erik-Ward Geerlings schreef voor deze succesvoorstelling een eigen speelse bewerking van Boccaccio’s meesterwerk. Dit voorjaar zet Arie de Mol, nu samen met de spelers van De Appel, zijn tanden opnieuw in deze tekst.

In de Decamerone ontvluchten tien vrouwen en mannen de stad Florence vanwege een pestepidemie. Tien dagen lang verblijven ze met elkaar in een villa in de heuvels en doden de tijd met eten, drinken, dansen en het vertellen van verhalen. Alle tien vertellen ze iedere dag één verhaal, waarmee ze de dagelijkse ellende proberen te bezweren. Na tien dagen zijn al improviserend honderd verhalen ontstaan. Verhalen over de liefde, het verstand, geluk, leugen en bedrog, de dood, seks en religie. Afhankelijk van wie vertelt zijn de verhalen ondeugend van toon, soms grof en gewelddadig, dan weer hoffelijk en elegant. Ze variëren van alledaagse anekdotes tot merkwaardige en wonderbaarlijke gebeurtenissen. Centrale leidraad in dit liefdeslabyrint is de ongelooflijke vindingrijkheid van de mens om uiteindelijk zijn zin te krijgen. List en leugen spelen een cruciale rol, zowel in de strijd om te overleven als in het spel van de liefde.

Samen met schrijver Erik-Ward Geerlings en dramaturg Mart-Jan Zegers maakte Arie de Mol een eigen toneelbewerking van Boccaccio’s meesterwerk, waarin een selectie uit de honderd verhalen tot leven komt. Het publiek wordt uitgenodigd de drukte van de stad achter zich te laten en zich in het Appeltheater een avond lang te laven aan eten, drinken en prachtige verhalen. Er zijn verschillende routes die u door het theater kunt volgen, elk met verrassende plekken waar u kunt genieten van steeds weer een ander mooi verhaal.

Giovanni Boccaccio was een Italiaans dichter en geleerde die in 1313 werd geboren in Florence. Decamerone betekent letterlijk: ‘het boek der tien dagen’. Boccaccio schreef deze verhalen in een periode waarin Italië werd geteisterd door oorlogen, hongersnood en epidemieën. De Decamerone gaat zowel over het leven van de aristocratie die zich probeerde af te sluiten voor al deze narigheid, als over het gewone volk dat dat harde bestaan zo goed mogelijk moest zien door te komen.

Op weg naar Decamerone op vrijdag 13 mei wordt een verrassend programma waarbij we alvast een tipje van de sluier oplichten over de nieuwe voorstelling Decamerone. Presentator Michiel van Zuijlen gaat in gesprek met regisseur Arie de Mol, toneelschrijver/bewerker Erik-Ward Geerlings en gast René van Stipriaan.

René van Stipriaan is literair-historicus en met name deskundig op het gebied van de Italiaanse Renaissance en in het bijzonder van het boek Decamerone. Verder lezen of spelen de acteurs scènes uit de voorstelling Decamerone.

Tijdens de speelperiode van Decamerone organiseert De Appel een uitgebreid programma met o.a. elke zaterdagmiddag een workshop, elke vrijdagavond Italiaanse Nacht (drank, dans en muziek) na afloop van de voorstelling. Dinsdag 21 juni organiseert De Appel Decamerone Nu, een avond waar migranten mooie verhalen uit hun land van herkomst vertellen. Alle informatie over deze programma’s leest u binnenkort op deze website.

Eten in het Appeltheater: Voorafgaand aan Decamerone kunt u geheel in de stijl van de voorstelling om 18.00 uur aan lange tafels een Italiaanse maaltijd gebruiken (niet op zondag). Het Appeltheater serveert een voorgerecht, hoofdgerecht en een nagerecht voor € 20,- per persoon. Er is ook een vegetarische variant. Het is niet mogelijk om een aparte tafel voor uw gezelschap te reserveren. Het eten is te bestellen via deze website of via de Appelkassa (tel. 070 3502200, dinsdag t/m vrijdag van 13.00 tot 17.00 uur).

Decamerone van Giovanni Boccaccio

Decamerone van Giovanni Boccaccio

bewerking Erik-Ward Geerlings

regie Arie de Mol

spel Marguerite de Brauw, Isabella Chapel, Lore Dijkman, David Geysen, Geert de Jong, Judith Linssen, Hugo Maerten, Bob Schwarze, Martijn van der Veen, Sjoerd Vrins, Iwan Walhain en Jessie Wilms

speelperiode woensdag 1 juni t/m zondag 3 juli 2016

aanvang 19.30 uur en zondag 14.30 uur, Appeltheater

Toneelgroep De Appel staat o.a. voor bijzondere en groot gemonteerde theaterproducties. Het gezelschap is wat betreft artistieke uitstraling en publieksbereik niet weg te denken uit het Nederlandse theaterlandschap.

De meeste voorstellingen worden gespeeld in het eigen Appeltheater. Een uniek gebouw waar het publiek steeds wordt verrast en zich in een andere omgeving waant. Het hart van het gezelschap wordt gevormd door het spelersensemble, onder leiding van Arie de Mol, waarin alle generaties zijn vertegenwoordigd.

Binnen het Nederlands toneel is een hecht ensemble een zeldzaam verschijnsel geworden. Voor De Appel is het ensemble essentieel. Dat betekent dat ook in de repertoirekeuze rekening wordt gehouden met een optimale bezetting vanuit het eigen ensemble. Natuurlijk worden er bij vrijwel iedere productie ook gastacteurs aangetrokken.

Toneelgroep De Appel/Appeltheater

Duinstraat 6 2584 AZ Den Haag tel. 070 3523344 (kantoor) tel. 0703502200 (kassa) algemeen@toneelgroepdeappel.nl

# Meer info voorstellingen, speellijst en kaartverkoop via website TONEELGROEPDEAPPEL

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Giovanni Boccaccio, THEATRE

Hans Christian Andersen: ‘Beautiful’

Alfred the sculptor – yes, you know him, don’t you? We all know him; he was awarded the gold medal, traveled to Italy, and came home again. He was young then; in fact, he is still young, though he is ten years older than he was at that time.

After he returned home, he visited one of the little provincial towns on the island of Zealand. The whole village knew who the stranger was, and in his honor one of the richest families gave a party. Everyone of any importance or owning any property was invited. It was quite an event, and all the village knew about it without its being announced by the town crier. Apprentice boys and the children of poor people, and even some of their parents, stood outside the house, looking at the lighted windows with their drawn curtains; and the watchman could imagine that he was giving the party, there were so many people in his street. There was an air of festivity everywhere, and inside the house, too, for Mr. Alfred the sculptor was there.

He talked and told stories, and everybody listened to him with pleasure and enthusiasm, but none more so than the elderly widow of a state official. As far as Mr. Alfred was concerned, she was like a blank sheet of gray blotting paper, absorbing everything that was said and demanding more. She was highly susceptible and unbelievably ignorant-a sort of female Kaspar Hauser.

“I should love to see Rome!” she said. “It must be a wonderful city, with all the many strangers continually arriving there. Now, do tell us what Rome is like. How does the city look when you come in by the gate?”

“It is not easy to describe it,” said the young sculptor. “There’s a great open place, and in the middle of it there is an obelisk that is four thousand years old.”

“An organist!” cried the lady, who had never heard the word “obelisk.”

Some of the guests could hardly keep from laughing, among them the sculptor, but the smile that rose to his lips quickly faded away, for he saw, close by the lady, a pair of dark-blue eyes; they belonged to the daughter of the lady who had been talking, and anyone with such a daughter could not really be silly! The mother was like a fountain of questions, and the daughter, who listened silently, might pass for the naiad of the fountain. How beautiful she was! She was something for a sculptor to look at, but not to speak with, for indeed she talked but very little.

“Has the Pope a large family?” asked the lady.

And the young man answered considerately, as if the question had been put differently, “No, he doesn’t come of a very great family.”

“That’s not what I mean,” said the lady. “I mean, does he have a wife and children?”

“The Pope isn’t allowed to marry,” he replied.

“I don’t approve of that,” said the lady.

She might well have talked and questioned him more intelligently, but if she hadn’t said and asked what she did, would her daughter have leaned so gracefully on her shoulder, looking straight before her with an almost melancholy smile on her lips?

And Mr. Alfred told them of the glorious colors of Italy, the purple of the mountains, the blue of the Mediterranean, the blue of the southern skies, a beauty that could only be surpassed in the North by the deep-blue eyes of a maiden. This he said with peculiar meaning, but she who should have understood it looked quite unconscious, and that, too, was charming!

“Ah, Italy!” sighed some of the guests.

“Traveling!” sighed others.

“Charming, charming!”

“Well,” said the widow, “if I win fifty thousand dollars in the lottery, we’ll travel! My daughter and I. You Mr. Alfred, must be our guide. We’ll all three go, with just one or two good friends with us.” Then she smiled in such a friendly manner at the company that each of them could imagine he was the person who would accompany them to Italy. “Yes, we’ll go to Italy! But not to the parts where the robbers are; we’ll stay in Rome and only travel by the great highways where we’ll be safe.”

And the daughter sighed very gently. And how much may lie in one little sigh or be read into it! The young man read a great deal into it. Those two blue eyes, bright that evening in his honor, must conceal treasures of heart and mind rarer than all the glories of Rome! When he left the party, he had lost his heart-lost it completely-to the young lady.

Now, the widow’s house was where Mr. Alfred the sculptor could most frequently be found. It was understood that his calls were not for the lady herself, though he and she did all the talking; he really came for the sake of the daughter. They called her Kala. Her real name was Karen Malene, but the two names had been contracted into the single name Kala. She was extremely, but some people said she was rather dull and probably slept late in the mornings.

“She has been accustomed to that since childhood,” said her mother. “She is as beautiful as Venus, and a beauty always tires easily. She does sleep rather late, but that’s what makes her eyes so bright.”

What a power there was in these clear eyes, these deep blue eyes! “Still waters run deep.” The young man felt the truth of that proverb, and his heart sank into the depths. He spoke of his adventures, and Mamma always asked the same naïve and pertinent questions she had asked at their first meeting.

It was a delight to hear Mr. Alfred speak. He told them of Naples, of trips to Mount Vesuvius, and showed them colored prints of some of the eruptions. The widow had never heard of such things before, much less taken time to think about them.

“Mercy save us!” she said. “So that’s a burning mountain! But isn’t it dangerous for the people who live there?”

“Entire cities have been destroyed,” he answered. “For example, Pompeii and Herculaneum.”

“Oh, the poor people! And you saw all that yourself?”

“Well, no, I didn’t see any of the eruptions shown in these pictures, but I’ll show you a drawing I made of an eruption I did see.”

He laid a pencil sketch on the table, and when Mamma, who had been studying the highly colored prints, glanced at the black-and-white drawing, she cried in amazement, “When you saw it did it throw up white fire?”

For a moment Alfred’s respect for Kala’s mamma nearly vanished; but then, dazzled by the light from Kala, he decided it was natural for the old lady to have no eye for color. After all, it didn’t matter, for Kala’s mamma had the most wonderful thing of all-she had Kala herself.

And Alfred and Kala were engaged, which was inevitable, and the engagement was announced in the town newspaper. Mamma brought thirty copies of the paper, so she could cut out the announcement and send it to her friends. The betrothed couple were happy, and the mamma-in-law-to-be was happy, too; she said it seemed like being related to Thorvaldsen himself.

“At any rate, you are his successor,” she told Alfred.

And it seemed to Alfred that Mamma had this time really said something clever. Kala said nothing, but her eyes sparkled; her every gesture was graceful. Yes, she was beautiful; that cannot be repeated too often.

Alfred made busts of Kala and his future mamma-in-law; they sat for him and watched how he molded and smoothed the soft clay between his fingers.

“I suppose it’s only for us that you do this common work,” said Mamma-in-law-to-be, “and don’t have your servant do all that dabbing together.”

“No, I have to mold the clay myself,” he explained.

“Oh, yes, you’re always so exceedingly polite,” said Mamma, while Kala silently pressed his hand, still soiled by the clay.

Then he unfolded to both of them the loveliness of nature in creation, explaining how the living stood higher in the scale than the dead, how the plant was above the mineral, the animal above the plant, and man above the animal, how mind and beauty are united in outward form, and how it was the task of the sculptor to seize that beauty and imprison it in his works.

Kala sat silent and nodded approval of the thought, while Mamma-in-law confessed, “It’s hard to follow all that. But my thoughts manage to hobble slowly along after you; they whirl around, but I try to hold them fast.”

And the power of Kala’s beauty held Alfred fast, seizing him and mastering him and filling his whole soul. There was beauty in Kala’s every feature; it sparkled in her eyes, lurked in the corners of her mouth and even in each movement of her fingers. The sculptor saw this; he spoke only of her, thought only of her, until the two became one. Thus it might be said that she also spoke often, for he was always talking of her, and they two were one.

Such was the betrothal; and now came the wedding day, with bridesmaids and presents, all duly mentioned in the wedding speech.

Mamma-in-law had set up a bust of Thorvaldsen, attired in a dressing gown, at one end of the table, for it was her whim that he was to be a guest. There were songs and toasts, for it was a gay wedding and they were a handsome pair. “Pygmalion gets his Galatea,” one of the songs said.

“That is something from mythology!” said Mamma-in-law.

Next day the young couple left for Copenhagen, where they were to live. Mamma-in-law went with them, “to give them a helping hand,” she explained-which meant to take charge of the house. Kala was to live in a doll’s house. Everything was so bright, new, and fine. There the three of them sat, and as for Alfred, to use a proverb that describes his circumstances, he sat like the bishop in the goose yard.

The magic of form had fascinated him. He had regarded the case and had no interest in learning what the case contained, and that is unfortunate, very unfortunate, in married life! If the case breaks and the gilding rubs off, the purchaser may repent of his bargain. It is very embarrassing to discover in a large party that one’s suspender buttons are coming off and that one has no belt to fall back on; but it is still worse to realize at a great party that one’s wife and mother-in-law are talking nonsense and that one cannot think of a clever piece of wit to cover up the stupidity of it.

The young couple often sat hand in hand, he speaking and she letting drop a word now and then-with always the same melody, like a clock striking the same two or three notes constantly. It was really a mental relief when one of her friends, Sophie, came to visit them.

Sophie wasn’t pretty. To be sure, she was not deformed; Kala always said she was a little crooked, but no one but a female friend would have noticed that. She was a very levelheaded girl and had no idea that she might ever become dangerous here. Her visits brought a fresh breath of air into the doll’s house, air that they all agreed was certainly needed there. But they felt they needed more airing, so they came out into the air, and Mamma-in-law and the young couple traveled to Italy.

“Thank heaven we are back in our own home again!” said both mother and daughter when they and Alfred returned home a year later.

“Traveling is no fun,” said Mamma-in-law. “On the contrary, it’s very tiring; pardon me for saying so. I found the time dragged, even though I had my children with me; and it is expensive, very expensive, to travel. All those galleries you have to see, and all the things you have to look at! You must do it for self-protection, because when you get back people are sure to ask you about them; and then they’re sure to tell you that you’ve missed the most worth-while things. I got so tired at last of those everlasting Madonnas; I thought I would turn into a Madonna myself!”

“And the food one gets!” said Kala.

“Yes,” agreed Mamma. “Not even a dish of honest meat soup! It is awful the way they cook!”

And Kala had become tired from traveling; she was always tired; that was the trouble. Sophie came to live with them, and her presence was a real help.

Mamma-in-law had to admit that Sophie understood both housekeeping and art, though you would hardly have expected a knowledge of the last from a person of her modest background. Moreover, she was honest and loyal; she showed that clearly when Kala lay sick, fading away.

If the case is everything, that case should be strong, or it is all over. And it was all over with the case-Kala died.

“She was so beautiful,” said Mamma. “She was very different from the antiques, because they’re all so damaged. Kala was completely perfect, just as a beauty should be.”

Alfred wept and the Mother wept, and both went into mourning. The black dresses became Mamma very well, so she wore her mourning the longer. Moreover, she soon experienced another grief, when she saw Alfred marry again. And he married Sophie, who had no looks at all!

“He has gone from one extreme to the other!” said Mamma-in-law. “Gone from the most beautiful to the ugliest! How could he forget his first wife! Men have no constancy. Now, my husband was entirely different, and he died before I did.”

“Pygmalion got his Galatea,” said Alfred. “Yes, that’s what the wedding song said. I really fell in love with a beautiful statue, which came to life in my arms, but the soul mate that heaven sends down to us, one of its angels who can comfort and sympathize with and uplift us, I have not found or won till now. You came to me, Sophie, not in the glory of superficial beauty – but fair enough, prettier than was necessary. The most important thing is still the most important. You came to teach a sculptor that his work is only clay and dust, only the outward form in a fabric that passes away, and that we must seek the spirit within. Poor Kala! Ours was but a wayfarer’s life. In the next world, where we shall come together through sympathy, we shall probably be half strangers to each other.

“That was not spoken kindly,” said Sophie, ” not like a true Christian. In the next world, where there is no marriage, but where, as you say, souls find each other through sympathy, where everything beautiful is developed and elevated, her soul may attain such completeness that it may resound far more melodiously than mine. Then you will again utter the first exciting cry of your love, ‘Beautiful, beautiful!'”

END

Hans Christian Andersen (1805—1875) fairy tales and stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andersen, Andersen, Hans Christian, Archive A-B, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Wilhelm Busch

(1832-1908)

Lieder eines Lumpen

1.

Als ich ein kleiner Bube war,

War ich ein kleiner Lump;

Zigarren raucht’ ich heimlich schon,

Trank auch schon Bier auf Pump.

Zur Hose hing das Hemd heraus,

Die Stiefel lief ich krumm,

Und statt zur Schule hinzugehn,

Strich ich im Wald herum.

Wie hab ich’s doch seit jener Zeit

So herrlich weit gebracht! –

Die Zeit hat aus dem kleinen Lump

‘nen grossen Lump gemacht.

2.

Der Mond und all die Sterne,

Die scheinen in der Nacht,

Hinwiederum die Sonne

Bei Tag am Himmel lacht.

Mit Sonne, Mond und Sternen

Bin ich schon lang vertraut!

Sie scheinen durch den Ärmel

Mir auf die blosse Haut.

Und was ich längst vermutet,

Das wird am Ende wahr:

Ich krieg’ am Ellenbogen

Noch Sommersprossen gar.

3.

Ich hatt’ einmal zehn Gulden! –

Da dacht’ ich hin und her,

Was mit den schönen Gulden

Nun wohl zu machen wär’.

Ich dacht’ an meine Schulden,

Ich dacht’ ans Liebchen mein,

Ich dacht’ auch ans Studieren,

Das fiel zuletzt mir ein.

Zum Lesen und Studieren,

Da muss man Bücher han,

Und jeder Manichäer

Ist auch ein Grobian;

Und obendrein das Liebchen,

Das Liebchen fromm und gut,

Das quälte mich schon lange

Um einen neuen Hut.

Was soll ich Ärmster machen?

Ich wusst nicht aus noch ein. –

Im Wirtshaus an der Brucken,

Da schenkt man guten Wein.

Im Wirtshaus an der Brucken

Sass ich den ganzen Tag,

Ich sass wohl bis zum Abend

Und sann den Dingen nach.

Im Wirtshaus an der Brucken,

Da wird der Dümmste Klug;

Des Nachts um halber zwölfe,

Da war ich klug genug.

Des Nachts um halber zwölfe

Hub ich mich von der Bank

Und zahlte meine Zeche

Mit zehen Gulden blank.

Ich zahlte meine Zeche,

Da war mein Beutel leer. –

Ich hatt’ einmal zehn Gulden,

Die hab’ ich jetzt nicht mehr.

4.

Im Karneval, da hab’ ich mich

Recht wohlfeil amüsiert,

Denn von Natur war ich ja schon

Fürtrefflich kostümiert.

Bei Maskeraden konnt’ ich so

Passieren frank und frei;

Man meinte am Entree, dass ich

Charaktermaske sei.

Recht unverschämt war ich dazu

Noch gegen jedermann

Und hab’ aus manchem fremden Glas

Manch tiefen Zug getan.

Darüber freuten sich die Leut

Und haben recht gelacht,

Dass ich den echten Lumpen so

Natürlich nachgemacht.

Nur einem groben Kupferschmied,

Dem macht’ es kein Pläsier,

Dass ich aus seinem Glase trank-

Er warf mich vor die Tür.

5.

Von einer alten Tante

Ward ich recht schön bedacht:

Sie hat fünfhundert Gulden

Beim Sterben mir vermacht..

Die gute alte Tante! –

Fürwahr, ich wünschte sehr,

Ich hätt’ noch mehr der Tanten

Und – hätt’ sie bald nicht mehr!

6.

Ich bin einmal hinausspaziert,

Hinaus wohl vor die Stadt.

Da kam es, dass ein Mädchen mir

Mein Herz gestohlen hat.

Ihr Aug war blau, ihr Mund war rot,

Blondlockig war ihr Haar. –

Mir tat’s in tiefster Seele weh,

Dass solch ein Lump ich war.

7.

Seit ich das liebe Mädchen sah,

War ich wie umgewandt,

Es hätte mich mein bester Freund

Wahrhaftig nicht gekannt.

Ich trug, fürwahr, Glacéhandschuh,

Glanzstiefel, Chapeau claque,

Vom feinsten Schnitt war das Gilet

Und magnifik der Frack.

Vom Fusse war ich bis zum Kopf

Ein Stutzer comme il faut,

Ich war, was mancher andre ist,

Ein Lump, inkognito.

8.

Was tat ich ihr zuliebe nicht!

Zum erstenmal im Leben

Hab’ ich mich neulich ihr zulieb

Auf einen Ball begeben.

Sie sah wie eine Blume aus

In ihrer Krinolinen,

Ich bin als schwarzer Käfer mir

In meinem Frack erschienen.

Für einen Käfer – welche Lust,

An einer Blume baumeln!

Für mich – welch Glück an ihrer Brust

Im Tanz dahinzutaumeln!

Doch ach! Mein schönes Käferglück,

Das war von kurzer Dauer;

Ein kläglich schnödes Missgeschick

Lag heimlich auf der Lauer.

Denn weiss der Teufel, wie’s geschah,

Es war so glatt im Saale –

Ich rutschte – und so lag ich da

Rumbums! Mit einem Male.

An ihrem seidenen Gewand

Dacht’ ich mich noch zu halten. –

Ritsch, ratsch! Da hielt ich in der Hand

Ein halbes Dutzend Falten.

Sie floh entsetzt. – Ich armer Tropf,

Ich meint’, ich müsst’ versinken,

Ich kratzte mir beschämt den Kopf

Und tät beiseite hinken.

9.

Den ganzen noblen Plunder soll,

Den soll der Teufel holen!

Ein Leutnant von der Garde hat

Mein Liebchen mir gestohlen.

Du neuer Hut, du neuer Frack,

Ihr müsst ins Pfandhaus wandern.

Ich selber sitz’ im Wirtshaus nun

Von einem Tag zum andern.

Ich sitz’ und trinke aus Verdruss

Und Ärger manchen Humpen.

Die Lieb, die mich solid gemacht,

Die macht mich nun zum Lumpen;

Und wem das Lied gefallen hat,

Der lasse sich nicht lumpen;

Der mög dem Lumpen, der es sang,

Zum Dank – ‘n Gulden pumpen.

Wilhelm Busch poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, CLASSIC POETRY, Wilhelm Busch

Wilhelm Busch

(1832-1908)

Summa summarum

Sag, wie wär es, alter Schragen,

Wenn du mal die Brille putztest,

Um ein wenig nachzuschlagen,