Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The perfect gift for book lovers: a beautifully designed hardcover in which two of the world’s great men have a delightfully rambling conversation about the future of the book in the digital era, and decide it is here to stay.

‘The book is like the spoon: once invented, it cannot be bettered.’ Umberto Eco These days it is almost impossible to get away from discussions of whether the ‘book’ will survive the digital revolution.

Blogs, tweets and newspaper articles on the subject appear daily, many of them repetitive, most of them admitting they don’t know what will happen. Amidst the twittering, the thoughts of Jean-Claude Carrière and Umberto Eco come as a breath of fresh air. There are few people better placed to discuss the past, present and future of the book. Both avid book collectors with a deep understanding of history, they have explored through their work the many and varied ways ideas have been represented through the ages.

Blogs, tweets and newspaper articles on the subject appear daily, many of them repetitive, most of them admitting they don’t know what will happen. Amidst the twittering, the thoughts of Jean-Claude Carrière and Umberto Eco come as a breath of fresh air. There are few people better placed to discuss the past, present and future of the book. Both avid book collectors with a deep understanding of history, they have explored through their work the many and varied ways ideas have been represented through the ages.

This thought-provoking book takes the form of a long conversation in which Carrière and Eco discuss everything from what can be defined as the first book to what is happening to knowledge now that infinite amounts of information are available at the click of a mouse. En route there are delightful digressions into personal anecdote. We find out about Eco’s first computer and the book Carrière is most sad to have sold.

Readers will close this entertaining book feeling they have had the privilege of eavesdropping on an intimate discussion between two great minds. And while, as Carrière says, the one certain thing about the future is that it is unpredictable, it is clear from this conversation that, in some form or other, the book will survive.

Umberto Eco (1932–2016) wrote fiction, literary criticism and philosophy. His first novel, The Name of the Rose, was a major international bestseller. His other works include Foucault’s Pendulum, The Island of the Day Before, Baudolino, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, The Prague Cemetery and Numero Zero along with many brilliant collections of essays.

Jean-Claude Carrière is a writer, playwright and screenwriter. He is notably the co-author of Conversations About the End of Time (with Stephen Jay Gould, Umberto Eco, etc.) He has also worked with Peter Brook, Milos Forman, Buñuel, Godard and the Dalaï Lama.

This is Not the End of the Book

A conversation curated by Jean-Philippe de Tonnac

By Umberto Eco, Jean-Claude Carrière

Language & Literary Studies

Paperback

ISBN 9780099552451

2012

Vintage Publ.

352 pages

$24.99

# new books

This is Not the End of the Book

Umberto Eco & Jean-Claude Carrière

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Archive E-F, Art & Literature News, The Art of Reading, Umberto Eco

Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back, edited by Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka and Daniel Sluman, is a ground-breaking anthology examining UK disabled and D/deaf poetics.

Packed with fierce poetry, essays, photos and links to accessible online videos and audio recordings, it showcases a diversity of opinions and survival strategies for an ableist world.

With contributions that span Vispo to Surrealism, and range from hard-hitting political commentary to intimate lyrical pieces, these poets refuse to perform or inspire according to tired old narratives.

With poetry & prose by: Aaron Williamson, Abi Palmer, Abigail Penny, Alec Finlay, Alison Smith, Andra Simons, Angela Readman, Bea Webster, Cath Nichols, Catherine Edmunds, Cathy Bryant, Claire Cunningham, Clare Hill, Colin Hambrook, Daniel Sluman, Debjani Chatterjee, Donna Williams, El Clarke, Eleanor Ward, Emily Ingram, Gary Austin Quinn, Georgi Gill, Giles L. Turnbull, Gram Joel Davies, Grant Tarbard, Holly Magill, Isha, Jackie Hagan, Jacqueline Pemberton, Joanne Limburg, Julie McNamara, Karen Hoy, Khairani Barokka, Kitty Coles, Kuli Kohli, Lisa Kelly, Lydia Popowich, Mark Mace Smith, Markie Burnhope, Michelle Green, Miki Byrne, Miss Jacqui, Naomi Woddis, Nuala Watt, Rachael Boast, Raisa Kabir, Raymond Antrobus, Rosamund McCullain, Rose Cook, Sandra Alland, Saradha Soobrayen, Sarah Golightley, sean burn, Stephanie Conn

With poetry & prose by: Aaron Williamson, Abi Palmer, Abigail Penny, Alec Finlay, Alison Smith, Andra Simons, Angela Readman, Bea Webster, Cath Nichols, Catherine Edmunds, Cathy Bryant, Claire Cunningham, Clare Hill, Colin Hambrook, Daniel Sluman, Debjani Chatterjee, Donna Williams, El Clarke, Eleanor Ward, Emily Ingram, Gary Austin Quinn, Georgi Gill, Giles L. Turnbull, Gram Joel Davies, Grant Tarbard, Holly Magill, Isha, Jackie Hagan, Jacqueline Pemberton, Joanne Limburg, Julie McNamara, Karen Hoy, Khairani Barokka, Kitty Coles, Kuli Kohli, Lisa Kelly, Lydia Popowich, Mark Mace Smith, Markie Burnhope, Michelle Green, Miki Byrne, Miss Jacqui, Naomi Woddis, Nuala Watt, Rachael Boast, Raisa Kabir, Raymond Antrobus, Rosamund McCullain, Rose Cook, Sandra Alland, Saradha Soobrayen, Sarah Golightley, sean burn, Stephanie Conn

About the Editors: Alland’s collections include Blissful Times (BookThug, 2007) and Naturally Speaking (espresso, 2012). Barokka’s works include Indigenous Species (Tilted Axis, 2016) and Rope (Nine Arches, 2017). Sluman has two books with Nine Arches: Absence has a weight of its own (2012) and The Terrible (2015).

Stairs and Whispers:

D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back

Edited by Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka & Daniel Sluman

Paperback

264 pages

Publisher: Nine Arches Press

2017

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1911027190

ISBN-13: 978-1911027195

Product Dimensions: 13.8 x 1 x 21.6 cm

eBook: Available at Amazon Kindle Store from September 2017

Discover the audio content that accompanies this book available on Soundcloud

Discover the video content that accompanies this book on Youtube

Price: £14.99

More information on website Nine Arches Press (http://ninearchespress.com/)

# more books

Stairs and Whispers:

D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, #More Poetry Archives, - Audiobooks, - Book News, - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, The Art of Reading

The Romancers

It was autumn in London, that blessed season between the harshness of winter and the insincerities of summer; a trustful season when one buys bulbs and sees to the registration of one’s vote, believing perpetually in spring and a change of Government.

Morton Crosby sat on a bench in a secluded corner of Hyde Park, lazily enjoying a cigarette and watching the slow grazing promenade of a pair of snow-geese, the male looking rather like an albino edition of the russet-hued female. Out of the corner of his eye Crosby also noted with some interest the hesitating hoverings of a human figure, which had passed and repassed his seat two or three times at shortening intervals, like a wary crow about to alight near some possibly edible morsel. Inevitably the figure came to an anchorage on the bench, within easy talking distance of its original occupant. The uncared-for clothes, the aggressive, grizzled beard, and the furtive, evasive eye of the new-comer bespoke the professional cadger, the man who would undergo hours of humiliating tale-spinning and rebuff rather than adventure on half a day’s decent work.

Morton Crosby sat on a bench in a secluded corner of Hyde Park, lazily enjoying a cigarette and watching the slow grazing promenade of a pair of snow-geese, the male looking rather like an albino edition of the russet-hued female. Out of the corner of his eye Crosby also noted with some interest the hesitating hoverings of a human figure, which had passed and repassed his seat two or three times at shortening intervals, like a wary crow about to alight near some possibly edible morsel. Inevitably the figure came to an anchorage on the bench, within easy talking distance of its original occupant. The uncared-for clothes, the aggressive, grizzled beard, and the furtive, evasive eye of the new-comer bespoke the professional cadger, the man who would undergo hours of humiliating tale-spinning and rebuff rather than adventure on half a day’s decent work.

For a while the new-comer fixed his eyes straight in front of him in a strenuous, unseeing gaze; then his voice broke out with the insinuating inflection of one who has a story to retail well worth any loiterer’s while to listen to.

“It’s a strange world,” he said.

As the statement met with no response he altered it to the form of a question.

“I daresay you’ve found it to be a strange world, mister?”

“As far as I am concerned,” said Crosby, “the strangeness has worn off in the course of thirty-six years.”

“Ah,” said the greybeard, “I could tell you things that you’d hardly believe. Marvellous things that have really happened to me.”

“Nowadays there is no demand for marvellous things that have really happened,” said Crosby discouragingly; “the professional writers of fiction turn these things out so much better. For instance, my neighbours tell me wonderful, incredible things that their Aberdeens and chows and borzois have done; I never listen to them. On the other hand, I have read ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’ three times.”

The greybeard moved uneasily in his seat; then he opened up new country.

“I take it that you are a professing Christian,” he observed.

“I am a prominent and I think I may say an influential member of the Mussulman community of Eastern Persia,” said Crosby, making an excursion himself into the realms of fiction.

The greybeard was obviously disconcerted at this new check to introductory conversation, but the defeat was only momentary.

“Persia. I should never have taken you for a Persian,” he remarked, with a somewhat aggrieved air.

“I am not,” said Crosby; “my father was an Afghan.”

“An Afghan!” said the other, smitten into bewildered silence for a moment. Then he recovered himself and renewed his attack.

“Afghanistan. Ah! We’ve had some wars with that country; now, I daresay, instead of fighting it we might have learned something from it. A very wealthy country, I believe. No real poverty there.”

He raised his voice on the word “poverty” with a suggestion of intense feeling. Crosby saw the opening and avoided it.

“It possesses, nevertheless, a number of highly talented and ingenious beggars,” he said; “if I had not spoken so disparagingly of marvellous things that have really happened I would tell you the story of Ibrahim and the eleven camel-loads of blotting-paper. Also I have forgotten exactly how it ended.”

“My own life-story is a curious one,” said the stranger, apparently stifling all desire to hear the history of Ibrahim; “I was not always as you see me now.”

“We are supposed to undergo complete change in the course of every seven years,” said Crosby, as an explanation of the foregoing announcement.

“I mean I was not always in such distressing circumstances as I am at present,” pursued the stranger doggedly.

“That sounds rather rude,” said Crosby stiffly, “considering that you are at present talking to a man reputed to be one of the most gifted conversationalists of the Afghan border.”

“I don’t mean in that way,” said the greybeard hastily; “I’ve been very much interested in your conversation. I was alluding to my unfortunate financial situation. You mayn’t hardly believe it, but at the present moment I am absolutely without a farthing. Don’t see any prospect of getting any money, either, for the next few days. I don’t suppose you’ve ever found yourself in such a position,” he added.

“In the town of Yom,” said Crosby, “which is in Southern Afghanistan, and which also happens to be my birthplace, there was a Chinese philosopher who used to say that one of the three chiefest human blessings was to be absolutely without money. I forget what the other two were.”

“Ah, I daresay,” said the stranger, in a tone that betrayed no enthusiasm for the philosopher’s memory; “and did he practise what he preached? That’s the test.”

“He lived happily with very little money or resources,” said Crosby.

“Then I expect he had friends who would help him liberally whenever he was in difficulties, such as I am in at present.”

“In Yom,” said Crosby, “it is not necessary to have friends in order to obtain help. Any citizen of Yom would help a stranger as a matter of course.”

The greybeard was now genuinely interested.

The conversation had at last taken a favourable turn.

“If someone, like me, for instance, who was in undeserved difficulties, asked a citizen of that town you speak of for a small loan to tide over a few days’ impecuniosity — five shillings, or perhaps a rather larger sum — would it be given to him as a matter of course?”

“There would be a certain preliminary,” said Crosby; “one would take him to a wine-shop and treat him to a measure of wine, and then, after a little high-flown conversation, one would put the desired sum in his hand and wish him good-day. It is a roundabout way of performing a simple transaction, but in the East all ways are roundabout.”

The listener’s eyes were glittering.

“Ah,” he exclaimed, with a thin sneer ringing meaningly through his words, “I suppose you’ve given up all those generous customs since you left your town. Don’t practise them now, I expect.”

“No one who has lived in Yom,” said Crosby fervently, “and remembers its green hills covered with apricot and almond trees, and the cold water that rushes down like a caress from the upland snows and dashes under the little wooden bridges, no one who remembers these things and treasures the memory of them would ever give up a single one of its unwritten laws and customs. To me they are as binding as though I still lived in that hallowed home of my youth.”

“Then if I was to ask you for a small loan —” began the greybeard fawningly, edging nearer on the seat and hurriedly wondering how large he might safely make his request, “if I was to ask you for, say —”

“At any other time, certainly,” said Crosby; “in the months of November and December, however, it is absolutely forbidden for anyone of our race to give or receive loans or gifts; in fact, one does not willingly speak of them. It is considered unlucky. We will therefore close this discussion.”

“But it is still October!” exclaimed the adventurer with an eager, angry whine, as Crosby rose from his seat; “wants eight days to the end of the month!”

“The Afghan November began yesterday,” said Crosby severely, and in another moment he was striding across the Park, leaving his recent companion scowling and muttering furiously on the seat.

“I don’t believe a word of his story,” he chattered to himself; “pack of nasty lies from beginning to end. Wish I’d told him so to his face. Calling himself an Afghan!”

The snorts and snarls that escaped from him for the next quarter of an hour went far to support the truth of the old saying that two of a trade never agree.

The Romancers

From ‘Beasts and Super-Beasts’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

For the last 2,500 years literature has been attacked, booed, and condemned, often for the wrong reasons and occasionally for very good ones. The Hatred of Literature examines the evolving idea of literature as seen through the eyes of its adversaries: philosophers, theologians, scientists, pedagogues, and even leaders of modern liberal democracies.

From Plato to C. P. Snow to Nicolas Sarkozy, literature’s haters have questioned the value of literature—its truthfulness, virtue, and usefulness—and have attempted to demonstrate its harmfulness.

From Plato to C. P. Snow to Nicolas Sarkozy, literature’s haters have questioned the value of literature—its truthfulness, virtue, and usefulness—and have attempted to demonstrate its harmfulness.

Literature does not start with Homer or Gilgamesh, William Marx says, but with Plato driving the poets out of the city, like God casting Adam and Eve out of Paradise. That is its genesis. From Plato the poets learned for the first time that they served not truth but merely the Muses. It is no mere coincidence that the love of wisdom (philosophia) coincided with the hatred of poetry. Literature was born of scandal, and scandal has defined it ever since.

In the long rhetorical war against literature, Marx identifies four indictments—in the name of authority, truth, morality, and society. This typology allows him to move in an associative way through the centuries. In describing the misplaced ambitions, corruptible powers, and abysmal failures of literature, anti-literary discourses make explicit what a given society came to expect from literature. In this way, anti-literature paradoxically asserts the validity of what it wishes to deny. The only threat to literature’s continued existence, Marx writes, is not hatred but indifference.

William Marx is Professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Paris Nanterre.

The Hatred of Literature

William Marx

Translated by Nicholas Elliott

Belknap Press

Harvard University Press

ISBN 9780674976122

Publ.: January 2018

Hardcover

240 pages

€27.00

# new books

William Marx – The Hatred of Literature

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, MONTAIGNE, The Art of Reading, The talk of the town

“The staggering thing about a life’s work is it takes a lifetime to complete,” Craig Morgan Teicher writes in these luminous essays.

We Begin in Gladness considers how poets start out, how they learn to hear themselves, and how some offer us that rare, glittering thing: lasting work. Teicher traces the poetic development of the works of Sylvia Plath, John Ashbery, Louise Glück, and Francine J. Harris, among others, to illuminate the paths they forged—by dramatic breakthroughs or by slow increments, and always by perseverance.

We Begin in Gladness considers how poets start out, how they learn to hear themselves, and how some offer us that rare, glittering thing: lasting work. Teicher traces the poetic development of the works of Sylvia Plath, John Ashbery, Louise Glück, and Francine J. Harris, among others, to illuminate the paths they forged—by dramatic breakthroughs or by slow increments, and always by perseverance.

We Begin in Gladness is indispensable for readers curious about the artistic life and for writers wondering how they might light out—or even scale the peak of the mountain.

Though it seems, at first, like an art of speaking, poetry is an art of listening. The poet trains to hear clearly and, as much as possible, without interruption, the voice of the mind, the voice that gathers, packs with meaning, and unpacks the language the poet knows.

It can take a long time to learn to let this voice speak without getting in its way. This slow learning, the growth of this habit of inner attentiveness, is poetic development, and it is the substance of the poet’s art. Of course, this growth is rarely steady, never linear, and is sometimes not actually growth but diminishment—that’s all part of the compelling story of a poet’s way forward. —from the Introduction

Craig Morgan Teicher is an acclaimed poet and critic. He is the author of We Begin in Gladness: How Poets Progress, and three books of poetry, including The Trembling Answers, winner of the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize, and he regularly writes reviews for Los Angeles Times, NPR, and the New York Times Book Review. He lives in New Jersey.

We Begin in Gladness.

How Poets Progress

by Craig Morgan Teicher

Publication Date 11/6/18

Format: Paperback

ISBN 978-1-55597-821-1

Subject: Literary Criticism

Pages 176

Graywolf Press

$16.00

# new books

more info: http://craigmorganteicher.com/

How Poets Progress

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Sylvia Plath, The Art of Reading

Aanstaande woensdag, 7 november, geeft schrijver Ton van Reen een lezing in de jaarlijkse lezingencyclus van het Dr. Winand Roukens Fonds, aan de Universiteit van Maastricht.

De lezing vindt plaats in de Karl Dittrichzaal van de Universiteit te Maastricht, in het voormalige Bonnefantenklooster, Bonnefantenstraat 2 te Maastricht.

De lezing vindt plaats in de Karl Dittrichzaal van de Universiteit te Maastricht, in het voormalige Bonnefantenklooster, Bonnefantenstraat 2 te Maastricht.

Het thema van de lezingencyclus van het WRF is in dit studiejaar ‘Vreemd in Limburg’.

De eerste lezing werd gehouden door prof. Joep Geraets, hoogleraar genetica en celbiologie over ‘vreemd DNA in Limburg’. De tweede werd gehouden door Dr. Lotte Thissen, cultureel antropoloog, en had als thema de taal waarin wij met elkaar omgaan. De derde lezing is door Ton van Reen. De vierde lezing, over arbeid door buitenlanders zoals Polen, wordt gehouden door Karolina Swoboda, eigenaar van een van de grootste organisaties voor arbeidsbemiddeling in Europa.

In zijn lezing zal Ton van Reen vooral vertellen over de mensen die niet bij ons mochten horen, de vreemdelingen in eigen huis. Omdat ze door de katholieke kerk benoemd waren tot kinderen van de duivel: de kubla walda, de kaboten, de kabouters. In het kort, de door de rk Kerk verstoten kinderen, zoals de kinderen die werden geboren met het syndroom van Down, die volgens de kerk duivelskinderen waren, omdat hun vader de duivel zou zijn en hun moeder omgang had met de duivel.

De rk Kerk heeft altijd de mensen die haar niet goed gezind waren, of van wie ze niet wilden dat ze katholiek werden, in verband gebracht met de duivel, zoals joden, roma en sinti, vrouwen die van hekserij werden beschuldigd, enzovoort.

De rk Kerk heeft altijd de mensen die haar niet goed gezind waren, of van wie ze niet wilden dat ze katholiek werden, in verband gebracht met de duivel, zoals joden, roma en sinti, vrouwen die van hekserij werden beschuldigd, enzovoort.

De duivel zou een geest zijn die zelf niet kon handelen , maar handlangers op aarde nodig had om zijn kwalijke werken uit te voeren, zoals misoogsten, uitbraken van pest en andere plagen, veeziektes , die tot hongersnoden hebben geleid, kinderroof, en zo meer.

Meer dan tien eeuwen lang heeft de kerk de mensen angst aangepraat voor alles wat anders was in de ogen van priesters en voor iedereen die anders dacht of een ander geloof aanhing.

Duizenden mensen, alleen al in het huidige Limburg, waren het slachtoffer van deze vervolgingen door een organisatie die zich boven alles verheven voelde en beschikte over leven en dood.

In de hele wereld werden er miljoenen mensen geslachtofferd en vaak na gruwelijke martelingen vermoord door een organisatie die zegt liefde te prediken maar haat heeft gezaaid en mensen tegen elkaar heeft opgezet.

Aanstaande woensdag, 7 november 2018, lezing van schrijver Ton van Reen in de jaarlijkse lezingencyclus van het Dr. Winand Roukens Fonds, aan de Universiteit van Maastricht.

De lezing vindt plaats in de Karl Dittrichzaal van de Universiteit te Maastricht, in het voormalige Bonnefantenklooster, Bonnefantenstraat 2 te Maastricht. De aanvang is om 16.00 uur. Graag iets eerder aanwezig. Einde om 18.00 uur. Iedereen is welkom.

# lezingen

Ton van Reen

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, Literary Events, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, The Art of Reading, Ton van Reen

Dusk

Norman Gortsby sat on a bench in the Park, with his back to a strip of bush-planted sward, fenced by the park railings, and the Row fronting him across a wide stretch of carriage drive. Hyde Park Corner, with its rattle and hoot of traffic, lay immediately to his right. It was some thirty minutes past six on an early March evening, and dusk had fallen heavily over the scene, dusk mitigated by some faint moonlight and many street lamps. There was a wide emptiness over road and sidewalk, and yet there were many unconsidered figures moving silently through the half-light, or dotted unobtrusively on bench and chair, scarcely to be distinguished from the shadowed gloom in which they sat.

The scene pleased Gortsby and harmonised with his present mood. Dusk, to his mind, was the hour of the defeated. Men and women, who had fought and lost, who hid their fallen fortunes and dead hopes as far as possible from the scrutiny of the curious, came forth in this hour of gloaming, when their shabby clothes and bowed shoulders and unhappy eyes might pass unnoticed, or, at any rate, unrecognised.

The scene pleased Gortsby and harmonised with his present mood. Dusk, to his mind, was the hour of the defeated. Men and women, who had fought and lost, who hid their fallen fortunes and dead hopes as far as possible from the scrutiny of the curious, came forth in this hour of gloaming, when their shabby clothes and bowed shoulders and unhappy eyes might pass unnoticed, or, at any rate, unrecognised.

A king that is conquered must see strange looks, So bitter a thing is the heart of man.

The wanderers in the dusk did not choose to have strange looks fasten on them, therefore they came out in this bat-fashion, taking their pleasure sadly in a pleasure-ground that had emptied of its rightful occupants. Beyond the sheltering screen of bushes and palings came a realm of brilliant lights and noisy, rushing traffic. A blazing, many-tiered stretch of windows shone through the dusk and almost dispersed it, marking the haunts of those other people, who held their own in life’s struggle, or at any rate had not had to admit failure. So Gortsby’s imagination pictured things as he sat on his bench in the almost deserted walk. He was in the mood to count himself among the defeated. Money troubles did not press on him; had he so wished he could have strolled into the thoroughfares of light and noise, and taken his place among the jostling ranks of those who enjoyed prosperity or struggled for it. He had failed in a more subtle ambition, and for the moment he was heartsore and disillusionised, and not disinclined to take a certain cynical pleasure in observing and labelling his fellow wanderers as they went their ways in the dark stretches between the lamp-lights.

On the bench by his side sat an elderly gentleman with a drooping air of defiance that was probably the remaining vestige of self-respect in an individual who had ceased to defy successfully anybody or anything. His clothes could scarcely be called shabby, at least they passed muster in the half-light, but one’s imagination could not have pictured the wearer embarking on the purchase of a half-crown box of chocolates or laying out ninepence on a carnation buttonhole. He belonged unmistakably to that forlorn orchestra to whose piping no one dances; he was one of the world’s lamenters who induce no responsive weeping. As he rose to go Gortsby imagined him returning to a home circle where he was snubbed and of no account, or to some bleak lodging where his ability to pay a weekly bill was the beginning and end of the interest he inspired. His retreating figure vanished slowly into the shadows, and his place on the bench was taken almost immediately by a young man, fairly well dressed but scarcely more cheerful of mien than his predecessor. As if to emphasise the fact that the world went badly with him the new-corner unburdened himself of an angry and very audible expletive as he flung himself into the seat.

“You don’t seem in a very good temper,” said Gortsby, judging that he was expected to take due notice of the demonstration.

The young man turned to him with a look of disarming frankness which put him instantly on his guard.

“You wouldn’t be in a good temper if you were in the fix I’m in,” he said; “I’ve done the silliest thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

“Yes?” said Gortsby dispassionately.

“Came up this afternoon, meaning to stay at the Patagonian Hotel in Berkshire Square,” continued the young man; “when I got there I found it had been pulled down some weeks ago and a cinema theatre run up on the site. The taxi driver recommended me to another hotel some way off and I went there. I just sent a letter to my people, giving them the address, and then I went out to buy some soap — I’d forgotten to pack any and I hate using hotel soap. Then I strolled about a bit, had a drink at a bar and looked at the shops, and when I came to turn my steps back to the hotel I suddenly realised that I didn’t remember its name or even what street it was in. There’s a nice predicament for a fellow who hasn’t any friends or connections in London! Of course I can wire to my people for the address, but they won’t have got my letter till tomorrow; meantime I’m without any money, came out with about a shilling on me, which went in buying the soap and getting the drink, and here I am, wandering about with twopence in my pocket and nowhere to go for the night.”

There was an eloquent pause after the story had been told. “I suppose you think I’ve spun you rather an impossible yarn,” said the young man presently, with a suggestion of resentment in his voice.

“Not at all impossible,” said Gortsby judicially; “I remember doing exactly the same thing once in a foreign capital, and on that occasion there were two of us, which made it more remarkable. Luckily we remembered that the hotel was on a sort of canal, and when we struck the canal we were able to find our way back to the hotel.”

The youth brightened at the reminiscence. “In a foreign city I wouldn’t mind so much,” he said; “one could go to one’s Consul and get the requisite help from him. Here in one’s own land one is far more derelict if one gets into a fix. Unless I can find some decent chap to swallow my story and lend me some money I seem likely to spend the night on the Embankment. I’m glad, anyhow, that you don’t think the story outrageously improbable.”

He threw a good deal of warmth into the last remark, as though perhaps to indicate his hope that Gortsby did not fall far short of the requisite decency.

“Of course,” said Gortsby slowly, “the weak point of your story is that you can’t produce the soap.”

The young man sat forward hurriedly, felt rapidly in the pockets of his overcoat, and then jumped to his feet.

“I must have lost it,” he muttered angrily.

“To lose an hotel and a cake of soap on one afternoon suggests wilful carelessness,” said Gortsby, but the young man scarcely waited to hear the end of the remark. He flitted away down the path, his head held high, with an air of somewhat jaded jauntiness.

“It was a pity,” mused Gortsby; “the going out to get one’s own soap was the one convincing touch in the whole story, and yet it was just that little detail that brought him to grief. If he had had the brilliant forethought to provide himself with a cake of soap, wrapped and sealed with all the solicitude of the chemist’s counter, he would have been a genius in his particular line. In his particular line genius certainly consists of an infinite capacity for taking precautions.”

With that reflection Gortsby rose to go; as he did so an exclamation of concern escaped him. Lying on the ground by the side of the bench was a small oval packet, wrapped and sealed with the solicitude of a chemist’s counter. It could be nothing else but a cake of soap, and it had evidently fallen out of the youth’s overcoat pocket when he flung himself down on the seat. In another moment Gortsby was scudding along the dusk-shrouded path in anxious quest for a youthful figure in a light overcoat. He had nearly given up the search when he caught sight of the object of his pursuit standing irresolutely on the border of the carriage drive, evidently uncertain whether to strike across the Park or make for the bustling pavements of Knightsbridge. He turned round sharply with an air of defensive hostility when he found Gortsby hailing him.

“The important witness to the genuineness of your story has turned up,” said Gortsby, holding out the cake of soap; “it must have slid out of your overcoat pocket when you sat down on the seat. I saw it on the ground after you left. You must excuse my disbelief, but appearances were really rather against you, and now, as I appealed to the testimony of the soap I think I ought to abide by its verdict. If the loan of a sovereign is any good to you —”

The young man hastily removed all doubt on the subject by pocketing the coin.

“Here is my card with my address,” continued Gortsby; “any day this week will do for returning the money, and here is the soap — don’t lose it again it’s been a good friend to you.”

“Lucky thing your finding it,” said the youth, and then, with a catch in his voice, he blurted out a word or two of thanks and fled headlong in the direction of Knightsbridge.

“Poor boy, he as nearly as possible broke down,” said Gortsby to himself. “I don’t wonder either; the relief from his quandary must have been acute. It’s a lesson to me not to be too clever in judging by circumstances.”

As Gortsby retraced his steps past the seat where the little drama had taken place he saw an elderly gentleman poking and peering beneath it and on all sides of it, and recognised his earlier fellow occupant.

“Have you lost anything, sir?” he asked.

“Yes, sir, a cake of soap.”

Dusk

From ‘Beasts and Super-Beasts’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

Laura

“You are not really dying, are you?” asked Amanda.

“I have the doctor’s permission to live till Tuesday,” said Laura.

“But today is Saturday; this is serious!” gasped Amanda.

“I don’t know about it being serious; it is certainly Saturday,” said Laura.

“Death is always serious,” said Amanda.

“I never said I was going to die. I am presumably going to leave off being Laura, but I shall go on being something. An animal of some kind, I suppose. You see, when one hasn’t been very good in the life one has just lived, one reincarnates in some lower organism. And I haven’t been very good, when one comes to think of it. I’ve been petty and mean and vindictive and all that sort of thing when circumstances have seemed to warrant it.”

“I never said I was going to die. I am presumably going to leave off being Laura, but I shall go on being something. An animal of some kind, I suppose. You see, when one hasn’t been very good in the life one has just lived, one reincarnates in some lower organism. And I haven’t been very good, when one comes to think of it. I’ve been petty and mean and vindictive and all that sort of thing when circumstances have seemed to warrant it.”

“Circumstances never warrant that sort of thing,” said Amanda hastily.

“If you don’t mind my saying so,” observed Laura, “Egbert is a circumstance that would warrant any amount of that sort of thing. You’re married to him — that’s different; you’ve sworn to love, honour, and endure him: I haven’t.”

“I don’t see what’s wrong with Egbert,” protested Amanda.

“Oh, I daresay the wrongness has been on my part,” admitted Laura dispassionately; “he has merely been the extenuating circumstance. He made a thin, peevish kind of fuss, for instance, when I took the collie puppies from the farm out for a run the other day.”

“They chased his young broods of speckled Sussex and drove two sitting hens off their nests, besides running all over the flower beds. You know how devoted he is to his poultry and garden.”

“Anyhow, he needn’t have gone on about it for the entire evening and then have said, ‘Let’s say no more about it’ just when I was beginning to enjoy the discussion. That’s where one of my petty vindictive revenges came in,” added Laura with an unrepentant chuckle; “I turned the entire family of speckled Sussex into his seedling shed the day after the puppy episode.”

“How could you?” exclaimed Amanda.

“It came quite easy,” said Laura; “two of the hens pretended to be laying at the time, but I was firm.”

“And we thought it was an accident!”

“You see,” resumed Laura, “I really have some grounds for supposing that my next incarnation will be in a lower organism. I shall be an animal of some kind. On the other hand, I haven’t been a bad sort in my way, so I think I may count on being a nice animal, something elegant and lively, with a love of fun. An otter, perhaps.”

“I can’t imagine you as an otter,” said Amanda.

“Well, I don’t suppose you can imagine me as an angel, if it comes to that,” said Laura.

Amanda was silent. She couldn’t.

“Personally I think an otter life would be rather enjoyable,” continued Laura; “salmon to eat all the year round, and the satisfaction of being able to fetch the trout in their own homes without having to wait for hours till they condescend to rise to the fly you’ve been dangling before them; and an elegant svelte figure —”

“Think of the otter hounds,” interposed Amanda; “how dreadful to be hunted and harried and finally worried to death!”

“Rather fun with half the neighbourhood looking on, and anyhow not worse than this Saturday-to-Tuesday business of dying by inches; and then I should go on into something else. If I had been a moderately good otter I suppose I should get back into human shape of some sort; probably something rather primitive — a little brown, unclothed Nubian boy, I should think.”

“I wish you would be serious,” sighed Amanda; “you really ought to be if you’re only going to live till Tuesday.”

As a matter of fact Laura died on Monday.

“So dreadfully upsetting,” Amanda complained to her uncle-inlaw, Sir Lulworth Quayne. “I’ve asked quite a lot of people down for golf and fishing, and the rhododendrons are just looking their best.”

“Laura always was inconsiderate,” said Sir Lulworth; “she was born during Goodwood week, with an Ambassador staying in the house who hated babies.”

“She had the maddest kind of ideas,” said Amanda; “do you know if there was any insanity in her family?”

“Insanity? No, I never heard of any. Her father lives in West Kensington, but I believe he’s sane on all other subjects.”

“She had an idea that she was going to be reincarnated as an otter,” said Amanda.

“One meets with those ideas of reincarnation so frequently, even in the West,” said Sir Lulworth, “that one can hardly set them down as being mad. And Laura was such an unaccountable person in this life that I should not like to lay down definite rules as to what she might be doing in an after state.”

“You think she really might have passed into some animal form?” asked Amanda. She was one of those who shape their opinions rather readily from the standpoint of those around them.

Just then Egbert entered the breakfast-room, wearing an air of bereavement that Laura’s demise would have been insufficient, in itself, to account for.

“Four of my speckled Sussex have been killed,” he exclaimed; “the very four that were to go to the show on Friday. One of them was dragged away and eaten right in the middle of that new carnation bed that I’ve been to such trouble and expense over. My best flower bed and my best fowls singled out for destruction; it almost seems as if the brute that did the deed had special knowledge how to be as devastating as possible in a short space of time.”

“Was it a fox, do you think?” asked Amanda.

“Sounds more like a polecat,” said Sir Lulworth.

“No,” said Egbert, “there were marks of webbed feet all over the place, and we followed the tracks down to the stream at the bottom of the garden; evidently an otter.”

Amanda looked quickly and furtively across at Sir Lulworth.

Egbert was too agitated to eat any breakfast, and went out to superintend the strengthening of the poultry yard defences.

“I think she might at least have waited till the funeral was over,” said Amanda in a scandalised voice.

“It’s her own funeral, you know,” said Sir Lulworth; “it’s a nice point in etiquette how far one ought to show respect to one’s own mortal remains.”

Disregard for mortuary convention was carried to further lengths next day; during the absence of the family at the funeral ceremony the remaining survivors of the speckled Sussex were massacred. The marauder’s line of retreat seemed to have embraced most of the flower beds on the lawn, but the strawberry beds in the lower garden had also suffered.

“I shall get the otter hounds to come here at the earliest possible moment,” said Egbert savagely.

“On no account! You can’t dream of such a thing!” exclaimed Amanda. “I mean, it wouldn’t do, so soon after a funeral in the house.”

“It’s a case of necessity,” said Egbert; “once an otter takes to that sort of thing it won’t stop.”

“Perhaps it will go elsewhere now there are no more fowls left,” suggested Amanda.

“One would think you wanted to shield the beast,” said Egbert.

“There’s been so little water in the stream lately,” objected Amanda; “it seems hardly sporting to hunt an animal when it has so little chance of taking refuge anywhere.”

“Good gracious!” fumed Egbert, “I’m not thinking about sport. I want to have the animal killed as soon as possible.”

Even Amanda’s opposition weakened when, during church time on the following Sunday, the otter made its way into the house, raided half a salmon from the larder and worried it into scaly fragments on the Persian rug in Egbert’s studio.

“We shall have it hiding under our beds and biting pieces out of our feet before long,” said Egbert, and from what Amanda knew of this particular otter she felt that the possibility was not a remote one.

On the evening preceding the day fixed for the hunt Amanda spent a solitary hour walking by the banks of the stream, making what she imagined to be hound noises. It was charitably supposed by those who overheard her performance, that she was practising for farmyard imitations at the forth-coming village entertainment.

It was her friend and neighbour, Aurora Burret, who brought her news of the day’s sport.

“Pity you weren’t out; we had quite a good day. We found at once, in the pool just below your garden.”

“Did you — kill?” asked Amanda.

“Rather. A fine she-otter. Your husband got rather badly bitten in trying to ‘tail it.’ Poor beast, I felt quite sorry for it, it had such a human look in its eyes when it was killed. You’ll call me silly, but do you know who the look reminded me of? My dear woman, what is the matter?”

When Amanda had recovered to a certain extent from her attack of nervous prostration Egbert took her to the Nile Valley to recuperate. Change of scene speedily brought about the desired recovery of health and mental balance. The escapades of an adventurous otter in search of a variation of diet were viewed in their proper light. Amanda’s normally placid temperament reasserted itself. Even a hurricane of shouted curses, coming from her husband’s dressing-room, in her husband’s voice, but hardly in his usual vocabulary, failed to disturb her serenity as she made a leisurely toilet one evening in a Cairo hotel.

“What is the matter? What has happened?” she asked in amused curiosity.

“The little beast has thrown all my clean shirts into the bath! Wait till I catch you, you little —”

“What little beast?” asked Amanda, suppressing a desire to laugh; Egbert’s language was so hopelessly inadequate to express his outraged feelings.

“A little beast of a naked brown Nubian boy,” spluttered Egbert.

And now Amanda is seriously ill.

Laura

From ‘Beasts and Super-Beasts’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

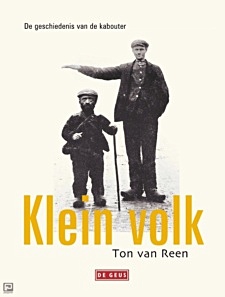

In Anagnorisis: Poems, the award-winning poet Kyle Dargan ignites a reckoning.

From the depths of his rapidly changing home of Washington, D.C., the poet is both enthralled and provoked, having witnessed-on a digital loop running in the background of Barack Obama‘s unlikely presidency—the rampant state-sanctioned murder of fellow African Americans.

From the depths of his rapidly changing home of Washington, D.C., the poet is both enthralled and provoked, having witnessed-on a digital loop running in the background of Barack Obama‘s unlikely presidency—the rampant state-sanctioned murder of fellow African Americans.

He is pushed toward the same recognition articulated by James Baldwin decades earlier: that an African American may never be considered an equal in citizenship or humanity.

This recognition—the moment at which a tragic hero realizes the true nature of his own character, condition, or relationship with an antagonistic entity—is what Aristotle called anagnorisis.

Not concerned with placatory gratitude nor with coddling the sensibilities of the country’s racial majority, Dargan challenges America: “You, friends- / you peckish for a peek / at my cloistered, incandescent / revelry-were you as earnest / about my frostbite, my burns, / I would have opened / these hands, sated you all.”

At a time when U.S. politics are heavily invested in the purported vulnerability of working-class and rural white Americans, these poems allow readers to examine themselves and the nation through the eyes of those who have been burned for centuries.

KYLE DARGAN is the author of four collections of poetry—Honest Engine (2015), Logorrhea Dementia (2010), Bouquet of Hungers (2007), and The Listening (2004). For his work, he has received the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and grants from the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities. His books also have been finalists for the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Book Award Grand Prize. Dargan has partnered with the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities to produce poetry programming at the White House and Library of Congress. He has worked with and supports a number of youth writing organizations, such as 826DC, Writopia Lab, and the Young Writers Workshop. He is currently an associate professor of literature and director of creative writing at American University, as well as the founder and editor of POST NO ILLS magazine.

Anagnorisis.

Poems

by Kyle Dargan (Author)

Publication Date

September 2018

Categories

Poetry

African-American Studies

Social Science/Cultural Studies

Trade Paper – $18.00

ISBN 978-0-8101-3784-4

96 pages

Size 6 x 9

Northwestern University Press

# new poetry

Kyle Dargan

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, James Baldwin, The Art of Reading

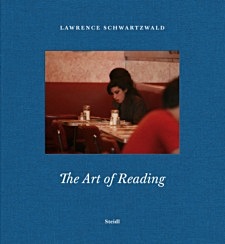

The Art of Reading presents the first retrospective of Lawrence Schwartzwald’s candid images of readers, made between 2001 and 2017.

Partly inspired by André Kertész’s On Reading of 1971, Schwartzwald’s subjects are mostly average New Yorkers—sunbathers, a bus driver, shoeshine men, subway passengers, denizens of bookshops and cafes—but also artists, most notably Amy Winehouse at Manhattan’s now-closed all-night diner Florent.

Partly inspired by André Kertész’s On Reading of 1971, Schwartzwald’s subjects are mostly average New Yorkers—sunbathers, a bus driver, shoeshine men, subway passengers, denizens of bookshops and cafes—but also artists, most notably Amy Winehouse at Manhattan’s now-closed all-night diner Florent.

In 2001 Schwartzwald’s affectionate photo of a New York bookseller reading at his makeshift sidewalk stand on Columbus Avenue (and inadvertently exposing his generous buttock cleavage) caused a minor sensation: first published in the New York Post, it inspired a reporter for the New York Observer to interview the “portly peddler” in a humorous column titled “Wisecracking on Columbus Avenue” of 2001.

Since then Schwartzwald has sought out his readers of books on paper—mostly solitary and often incongruous, desperate or vulnerable—who fly in the face of the closure of traditional bookshops and the surge in e-books, dedicating themselves to what Schwartzwald sees as a vanishing art: the art of reading.

Lawrence Schwartzwald: Born in New York in 1953, Lawrence Schwartzwald studied literature at New York University. He worked as a freelance photographer for the New York Post for nearly two decades and in 1997 New York Magazine dubbed him the Post’s “king of the streets.” Books and literature have shaped several of his photo series including “Reading New York” and “Famous Poets,” both self-published in 2017. Schwartzwald lives and works in Manhattan.

Lawrence Schwartzwald

The Art of Reading

published by Steidl

Hardback / Clothbound

22 x 23 cm

English

ISBN 978-3-95829-508-7

1. Edition 06/2018

€ 28.00

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, LITERARY MAGAZINES, PRESS & PUBLISHING, The Art of Reading

The story of how literature shaped world history, in sixteen acts—from Alexander the Great and the Iliad to Don Quixote and Harry Potter

In this groundbreaking book, Martin Puchner leads us on a remarkable journey through time and around the globe to reveal the powerful role stories and literature have played in creating the world we have today.

In this groundbreaking book, Martin Puchner leads us on a remarkable journey through time and around the globe to reveal the powerful role stories and literature have played in creating the world we have today.

Puchner introduces us to numerous visionaries as he explores sixteen foundational texts selected from more than four thousand years of world literature and reveals how writing has inspired the rise and fall of empires and nations, the spark of philosophical and political ideas, and the birth of religious beliefs. Indeed, literature has touched the lives of generations and changed the course of history.

At the heart of this book are works, some long-lost and rediscovered, that have shaped civilization: the first written masterpiece, the Epic of Gilgamesh; Ezra’s Hebrew Bible, created as scripture; the teachings of Buddha, Confucius, Socrates, and Jesus; and the first great novel in world literature, The Tale of Genji, written by a Japanese woman known as Murasaki. Visiting Baghdad, Puchner tells of Scheherazade and the stories of One Thousand and One Nights, and in the Americas we watch the astonishing survival of the Maya epic Popol Vuh. Cervantes, who invented the modern novel, battles pirates both real (when he is taken prisoner) and literary (when a fake sequel to Don Quixote is published).

We learn of Benjamin Franklin’s pioneering work as a media entrepreneur, watch Goethe discover world literature in Sicily, and follow the rise in influence of The Communist Manifesto. We visit Troy, Pergamum, and China, and we speak with Nobel laureates Derek Walcott in the Caribbean and Orhan Pamuk in Istanbul, as well as the wordsmiths of the oral epic Sunjata in West Africa.

Throughout The Written World, Puchner’s delightful narrative also chronicles the inventions—writing technologies, the printing press, the book itself—that have shaped religion, politics, commerce, people, and history. In a book that Elaine Scarry has praised as “unique and spellbinding,” Puchner shows how literature turned our planet into a written world.

Title: The Written World

Subtitle: The Power of Stories to Shape People, History, Civilization

Author: Martin Puchner

Publisher: Random House

Format Hardcover, $32.00

ISBN-10 0812998936

ISBN-13 9780812998931

Publication Date: 24 October 2017

Nb of pages 448 p.

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Libraries in Literature, PRESS & PUBLISHING, The Art of Reading

A wonderfully digressive little volume about our complex relationship with our books and being an incurable bibliophile. The perfect antidote to Walter Benjamin’s classic essay, Unpacking My Library.

A best-selling author and world-renowned bibliophile meditates on his vast personal library and champions the vital role of all libraries.

A best-selling author and world-renowned bibliophile meditates on his vast personal library and champions the vital role of all libraries.

In June 2015 Alberto Manguel prepared to leave his centuries-old village home in France’s Loire Valley and reestablish himself in a one-bedroom apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Packing up his enormous, 35,000‑volume personal library, choosing which books to keep, store, or cast out, Manguel found himself in deep reverie on the nature of relationships between books and readers, books and collectors, order and disorder, memory and reading. In this poignant and personal reevaluation of his life as a reader, the author illuminates the highly personal art of reading and affirms the vital role of public libraries.

Manguel’s musings range widely, from delightful reflections on the idiosyncrasies of book lovers to deeper analyses of historic and catastrophic book events, including the burning of ancient Alexandria’s library and contemporary library lootings at the hands of ISIS. With insight and passion, the author underscores the universal centrality of books and their unique importance to a democratic, civilized, and engaged society.

Alberto Manguel is a writer, translator, editor, and critic, but would rather define himself as a reader and a lover of books. Born in Buenos Aires, he has since resided in Israel, Argentina, Europe, the South Pacific, and Canada. He is now the director of the National Library of Argentina.

Title: Packing My Library

Subtitle: An Elegy and Ten Digressions

Author: Alberto Manguel

Publisher: Yale University Press

Title First Published: 20 March 2018

Format: Hardcover

ISBN-10 0300219334

ISBN-13 9780300219333

Nb of pages 160 p.

Hardcover – $23.00

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, Alberto Manguel, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, Libraries in Literature, The Art of Reading

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature