Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Carolyn’s not so different from the other people around her. She likes guacamole and cigarettes and steak. She knows how to use a phone. Clothes are a bit tricky, but everyone says nice things about her outfit with the Christmas sweater over the gold bicycle shorts.

After all, she was a normal American herself once. That was a long time ago, of course. Before her parents died. Before she and the others were taken in by the man they called Father.

After all, she was a normal American herself once. That was a long time ago, of course. Before her parents died. Before she and the others were taken in by the man they called Father.

In the years since then, Carolyn hasn’t had a chance to get out much. Instead, she and her adopted siblings have been raised according to Father’s ancient customs. They’ve studied the books in his Library and learned some of the secrets of his power.

And sometimes, they’ve wondered if their cruel tutor might secretly be God. Now, Father is missing—perhaps even dead—and the Library that holds his secrets stands unguarded. And with it, control over all of creation.

As Carolyn gathers the tools she needs for the battle to come, fierce competitors for this prize align against her, all of them with powers that far exceed her own. But Carolyn has accounted for this. And Carolyn has a plan. The only trouble is that in the war to make a new God, she’s forgotten to protect the things that make her human.

Populated by an unforgettable cast of characters and propelled by a plot that will shock you again and again, The Library at Mount Char is at once horrifying and hilarious, mind-blowingly alien and heartbreakingly human, sweepingly visionary and nail-bitingly thrilling—and signals the arrival of a major new voice in fantasy. (From the Hardcover edition.)

“Wholly original…the work of the newest major talent in fantasy.”

Wall Street Journal

SCOTT HAWKINS works as a software engineer for Intel. He and his wife live in Atlanta, where they spend much of their time playing Olympic-caliber fetch with their large pack of foster dogs. THE LIBRARY AT MOUNT CHAR is his first novel.

The Library at Mount Char

By Scott Hawkins

Category: Contemporary Fantasy

Paperback

Penguin Random House

2016, 400 Pages

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Libraries in Literature

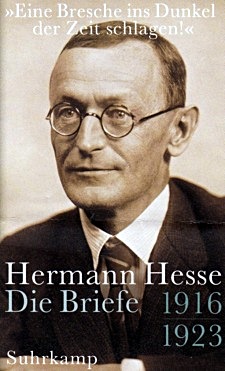

Als erfolgreicher Autor des berühmten S. Fischer Verlags, dem er seit 1904 angehörte, war Hermann Hesse (1877-1962) in besonderer Weise mit Berlin verbunden, wenngleich er selbst nur ganz selten hier war.

Die Machtübernahme durch die Nationalsozialisten hatte auch für Hesse, der seit 1924 wieder Schweizer Staatsbürger war und im Tessin lebte, weitreichende Konsequenzen, da ihn die Bindung an seinen Berliner Verlag in Abhängigkeit vom nationalsozialistischen Regime brachte, dessen Propagandisten ihn anfangs diffamierten und später ausmanövrierten.

Die Machtübernahme durch die Nationalsozialisten hatte auch für Hesse, der seit 1924 wieder Schweizer Staatsbürger war und im Tessin lebte, weitreichende Konsequenzen, da ihn die Bindung an seinen Berliner Verlag in Abhängigkeit vom nationalsozialistischen Regime brachte, dessen Propagandisten ihn anfangs diffamierten und später ausmanövrierten.

Einflussreiche emigrierte Publizisten indessen verurteilten aufs schärfste, dass Hesse nicht gegen die Veröffentlichung seiner Bücher und Texte in Deutschland vorging und sich nicht ausschließlich zur deutschen Exilliteratur bekannte.

Redakteure Schweizer Zeitungen wiederum warfen Hesse mangelndes Verständnis des Schweizer Antisemitismus vor, der Anfang 1936 eine Niederlassung in Zürich des ins Exil getriebenen Teils des S. Fischer Verlags unausgesprochen mit verhindert hatte.

Fokussiert auf die Jahre von 1933 bis 1947, thematisiert die Ausstellung anhand vieler bislang unbekannter Materialien die vielschichtigen Verflechtungen, die Hesse zwischen der Schweiz, der deutschen Emigration und der Diktatur in Deutschland buchstäblich „zwischen die Fronten“ geraten ließ.

Anlass für die Ausstellung ist die Möglichkeit, aus dem umfangreichen, bislang unveröffentlichten Briefwechsel Hesses mit seinem jüngsten Sohn Martin (1911-1968) einige ausgewählte Briefe präsentieren und dem Zeitgeschehen zuordnen zu können. Im Frühjahr 1932 hatte Martin Hesse noch einen Vorkurs am Bauhaus in Dessau belegen können und erlebte dort die politische Radikalisierung Deutschlands.

Anlass für die Ausstellung ist die Möglichkeit, aus dem umfangreichen, bislang unveröffentlichten Briefwechsel Hesses mit seinem jüngsten Sohn Martin (1911-1968) einige ausgewählte Briefe präsentieren und dem Zeitgeschehen zuordnen zu können. Im Frühjahr 1932 hatte Martin Hesse noch einen Vorkurs am Bauhaus in Dessau belegen können und erlebte dort die politische Radikalisierung Deutschlands.

In die Schweiz zurückgekehrt, entwickelte Martin Hesse aus der am Bauhaus angeregten Beschäftigung mit der Fotografie eine professionelle Passion: Von ihm stammen die beeindruckenden Aufnahmen der Kunstdenkmäler des Kantons Bern und unzählige Fotos seines berühmten Vaters.

Die Ausstellung setzt mit einem Rückblick auf Hesses erste Frau Maria (Mia), geb. Bernoulli (1868-1963), ein, mit der er bis 1912 in Gaienhofen am Bodensee gelebt hatte. Maria Bernoulli gilt als die erste Schweizer Berufsfotografin, zusammen mit ihrer Schwester unterhielt sie von 1902 bis 1907 ein Fotoatelier in Basel.

Eine Ausstellung des Literaturhauses Berlin

Konzipiert von Lutz Dittrich mit Unterstützung durch Gunnar Decker und Volker Michels

Mitarbeit: Sebastian Januszewski

Ausstellungsgestaltung: unodue { (Costanza Puglisi und Florian Wenz)

Einen Folder mit umfangreichen Informationen über die Ausstellung finden Sie auch hier.

Die zur Ausstellung erscheinende Begleitpublikation

Zwischen den Fronten. Der Glasperlenspieler Hermann Hesse enthält einige ausgewählte Abdrucke aus dem Briefwechsel Hermann Hesses mit seinem Sohn Martin sowie Originalbeiträge von Jan-Pieter Barbian (Publizist), Gunnar Decker (Hesse-Biograph), Michael Kleeberg (Schriftsteller und Übersetzer) und Volker Michels (Hesse-Herausgeber).

In der Ausstellung erhältlich.

Hg. von Lutz Dittrich.

12.- Euro.

ISBN 978-3-926433-57-2

14 Dez – 11 Mär 2017

Grosser und Kleiner Saal

Ausstellung im Literaturhaus

Zwischen den Fronten.

Der Glasperlenspieler Hermann Hesse

LiteraturHausBerlin

Fasanenstraße 23

10719 Berlin

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Hermann Hesse, Hesse, Hermann

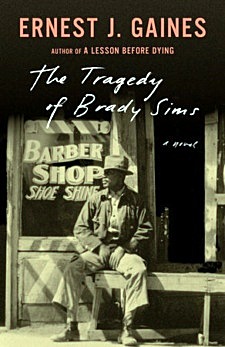

Ernest J. Gaines’s new novella revolves around a courthouse shooting that leads a young reporter to uncover the long story of race and power in his small town and the relationship between the white sheriff and the black man who “whipped children” to keep order.

After Brady Sims pulls out a gun in a courtroom and shoots his own son, who has just been convicted of robbery and murder, he asks only to be allowed two hours before he’ll give himself up to the sheriff. When the editor of the local newspaper asks his cub reporter to dig up a “human interest” story about Brady, he heads for the town’s barbershop. It is the barbers and the regulars who hang out there who narrate with empathy, sadness, humor, and a profound understanding the life story of Brady Sims—an honorable, just, and unsparing man who with his tough love had been handed the task of keeping the black children of Bayonne, Louisiana in line to protect them from the unjust world in which they lived. And when his own son makes a fateful mistake, it is up to Brady to carry out the necessary reckoning. In the telling, we learn the story of a small southern town, divided by race, and the black community struggling to survive even as many of its inhabitants head off northwards during the Great Migration.

After Brady Sims pulls out a gun in a courtroom and shoots his own son, who has just been convicted of robbery and murder, he asks only to be allowed two hours before he’ll give himself up to the sheriff. When the editor of the local newspaper asks his cub reporter to dig up a “human interest” story about Brady, he heads for the town’s barbershop. It is the barbers and the regulars who hang out there who narrate with empathy, sadness, humor, and a profound understanding the life story of Brady Sims—an honorable, just, and unsparing man who with his tough love had been handed the task of keeping the black children of Bayonne, Louisiana in line to protect them from the unjust world in which they lived. And when his own son makes a fateful mistake, it is up to Brady to carry out the necessary reckoning. In the telling, we learn the story of a small southern town, divided by race, and the black community struggling to survive even as many of its inhabitants head off northwards during the Great Migration.

Ernest Gaines was born on a plantation in Pointe Coupee Parish near New Roads, Louisiana, which is the Bayonne of all his fictional works. He is a writer-in-residence emeritus at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Gaines received a MacArthur Fellowship in 1993 for his lifetime achievements; was named a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, one of France’s highest decorations, in 1996; and was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2004. He and his wife, Dianne, live in Oscar, Louisiana.

“A taut and searing tale about race and small-town justice. . . . The history the men recount is, indeed, riveting in its insights into how racism harms everyone, crystallized in Mapes’ heartbroken tribute to his friend: ‘Hell of a man, that Brady Sims.’ Gaines tells a hell of a story.” – Donna Seaman, Booklist

The Tragedy of Brady Sims

By Ernest J. Gaines

Part of Vintage Contemporaries

Literary Fiction | Crime Mysteries

Paperback

Publ. Penguin Random House

Aug 29, 2017

128 Pages

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Racism

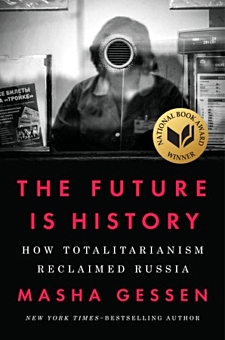

The visionary journalist and bestselling biographer of Vladimir Putin reveals how, in the space of a generation, Russia surrendered to a more virulent and invincible new strain of autocracy.

Hailed for her “fearless indictment of the most powerful man in Russia” (The Wall Street Journal), award-winning journalist Masha Gessen is unparalleled in her understanding of the events and forces that have wracked her native country in recent times.

Hailed for her “fearless indictment of the most powerful man in Russia” (The Wall Street Journal), award-winning journalist Masha Gessen is unparalleled in her understanding of the events and forces that have wracked her native country in recent times.

In The Future Is History, she follows the lives of four people born at what promised to be the dawn of democracy. Each of them came of age with unprecedented expectations, some as the children and grandchildren of the very architects of the new Russia, each with newfound aspirations of their own—as entrepreneurs, activists, thinkers, and writers, sexual and social beings.

Gessen charts their paths against the machinations of the regime that would crush them all, and against the war it waged on understanding itself, which ensured the unobstructed reemergence of the old Soviet order in the form of today’s terrifying and seemingly unstoppable mafia state. Powerful and urgent, The Future Is History is a cautionary tale for our time and for all time.

Masha Gessen’s previous books include The Brothers: The Road to an American Tragedy and the national best seller The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin. She has immigrated to the United States twice—once, as a teenager, from the Soviet Union and again, more than thirty years later, from Putin’s Russia. She lives in New York City.

Masha Gessen

The Future Is History

How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia

Hardcover

October 2017

528 Pages

ISBN 9781594634536

Published by Riverhead Books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, PRESS & PUBLISHING, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS, WAR & PEACE

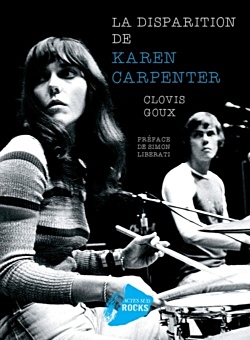

Durant les années 1970, The Carpenters est le groupe le plus populaire aux États-Unis.

Un immense succès (100 millions de disques vendus) qui s’explique par l’alchimie unique entre ses deux membres fondateurs, Richard et Karen Carpenter, un frère et une sœur. Ces deux enfants de la classe moyenne imposent un retour à l’ordre musical après la révolution psychédélique, avec des hits aussi romantiques que réactionnaires, tels Close to you, We’ve Only Just Begun ou Rainy Days and Mondays. Mais derrière cette success story se cache une tragédie.

Un immense succès (100 millions de disques vendus) qui s’explique par l’alchimie unique entre ses deux membres fondateurs, Richard et Karen Carpenter, un frère et une sœur. Ces deux enfants de la classe moyenne imposent un retour à l’ordre musical après la révolution psychédélique, avec des hits aussi romantiques que réactionnaires, tels Close to you, We’ve Only Just Begun ou Rainy Days and Mondays. Mais derrière cette success story se cache une tragédie.

La Disparition de Karen Carpenter raconte cette histoire, nous amenant à porter un regard de côté sur les grands phénomènes socio-culturels qui marquèrent l’Amérique de l’époque.

Clovis Goux est journaliste indépendant et cofondateur du label Dirty.

Clovis Goux

La Disparition de Karen Carpenter

Simon Liberati – Préfacier

Actes Sud Rocks

Septembre, 2017

132 pages

ISBN 978-2-330-08129-4

prix indicatif: €15,00

Genre: Essais, Documents

Clovis Goux: La Disparition de Karen Carpenter

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, BIOGRAPHY, Karen Carpenter, Karen Carpenter

Here in Berlin is a portrait of a city through snapshots, an excavation of the stories and ghosts of contemporary Berlin—its complex, troubled past still pulsing in the air as it was during World War II. Critically acclaimed novelist Cristina García brings the people of this famed city to life, their stories bristling with regret, desire, and longing.

An unnamed Visitor travels to Berlin with a camera looking for reckonings of her own. The city itself is a character—vibrant and postapocalyptic, flat and featureless except for its rivers, its lakes, its legions of bicyclists. Here in Berlin she encounters a people’s history: the Cuban teen taken as a POW on a German submarine, only to return home to a family who doesn’t believe him; the young Jewish scholar hidden in a sarcophagus until safe passage to England is found; the female lawyer haunted by a childhood of deprivation in the bombed-out suburbs of Berlin who still defends those accused of war crimes; a young nurse with a checkered past who joins the Reich at a medical facility more intent to dispense with the wounded than to heal them; and the son of a zookeeper at the Berlin Zoo, fighting to keep the animals safe from both war and an increasingly starving populace.

An unnamed Visitor travels to Berlin with a camera looking for reckonings of her own. The city itself is a character—vibrant and postapocalyptic, flat and featureless except for its rivers, its lakes, its legions of bicyclists. Here in Berlin she encounters a people’s history: the Cuban teen taken as a POW on a German submarine, only to return home to a family who doesn’t believe him; the young Jewish scholar hidden in a sarcophagus until safe passage to England is found; the female lawyer haunted by a childhood of deprivation in the bombed-out suburbs of Berlin who still defends those accused of war crimes; a young nurse with a checkered past who joins the Reich at a medical facility more intent to dispense with the wounded than to heal them; and the son of a zookeeper at the Berlin Zoo, fighting to keep the animals safe from both war and an increasingly starving populace.

A meditation on war and mystery, this is an exciting new work by one of our most gifted novelists, one that seeks to align the stories of the past with the stories of the future.

Cristina Garcia is the author of seven novels, including Dreaming in Cuban, a finalist for the National Book Award that just celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary; The Agüero Sisters, Monkey Hunting, A Handbook to Luck, The Lady Matador’s Hotel, and King of Cuba. Her work has been translated into fourteen languages. García has edited anthologies, written children’s books, published poetry, and taught at universities nationwide. She lives in the San Francisco Bay area.

Title: Here in Berlin

Subtitle: A Novel

Author: Cristina García

Publisher: Counterpoint

Format Hardcover

ISBN-10 1619029596

ISBN-13 9781619029590

Publication October 2017

Main content pages 224

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, FDM in Berlin, Photography

Un homme a écrit un énorme scénario sur la vie de Herman Melville : The Great Melville, dont aucun producteur ne veut.

Un jour, on lui procure le numéro de téléphone du grand cinéaste américain Michael Cimino, le réalisateur mythique de Voyage au bout de l’enfer et de La Porte du paradis. Une rencontre a lieu à New York : Cimino lit le manuscrit.

Un jour, on lui procure le numéro de téléphone du grand cinéaste américain Michael Cimino, le réalisateur mythique de Voyage au bout de l’enfer et de La Porte du paradis. Une rencontre a lieu à New York : Cimino lit le manuscrit.

S’ensuivent une série d’aventures rocambolesques entre le musée de la Chasse à Paris, l’île d’Ellis Island au large de New York, et un lac en Italie.

On y croise Isabelle Huppert, la déesse Diane, un dalmatien nommé Sabbat, un voisin démoniaque et deux moustachus louches ; il y a aussi une jolie thésarde, une concierge retorse et un très agressif maître d’hôtel sosie d’Emmanuel Macron.

Quelle vérité scintille entre cinéma et littérature?

La comédie de notre vie cache une histoire sacrée : ce roman part à sa recherche.

Yannick Haenel

Tiens ferme ta couronne

Collection L’Infini, Gallimard

Parution : 17-08-2017

ISBN : 9782070177875

352 pages, 140 x 205 mm

Achevé d’imprimer : 12-06-2017

Prix €20,00

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes

A young man wakes up at dawn to drive to the Andes, to climb the Cerro Bonete–a mountain untouched by ice axes and climbers, one of the planet’s final mountains to be conquered–as an act of heroic bravado, or foolishness.

But instead, he finds himself dragged, by the undertow of memory, to Esplanada, the neighborhood he grew up in, to the brotherhood of his old friends, and to the clearing in the woods where he witnessed an act that has run like a scar through the rest of his life.

But instead, he finds himself dragged, by the undertow of memory, to Esplanada, the neighborhood he grew up in, to the brotherhood of his old friends, and to the clearing in the woods where he witnessed an act that has run like a scar through the rest of his life.

Back in Esplanada, the young man revisits his initiation into adulthood and recalls his boyhood friends who formed a strange and volatile pack. Together they play video games, get drunk around bonfires, pick fights, and goad each other into bike races where the winner is the boy who has the most spectacular crash. Caught between the threat of not being man enough, the desire to please his friends, and the intoxicating contact-high of danger, the boy finds himself following the rules of the pack even as the risks mount. And in a moment that reverberates and repeats itself in new ways in his adulthood, his fantasies of who he is and what it means to be a man come crashing down, and life asserts itself as an endless rehearsal for a heroic moment that may never arrive.

From one of Brazil’s most dazzling writers, The Shape of Bones is an exhilarating story of mythic power. Daniel Galera has written a pulse-racing novel with the otherworldly wisdom of a parable.

Daniel Galera is a Brazilian writer, translator, and editor. He was born in Sao Paolo, but spent most of his life in Porto Alegre, only returning to Sao Paulo in 2005. He has published four novels in Brazil to great acclaim, the latest of which, Blood-Drenched Beard, was awarded the 2013 Sao Paolo Literature Prize. In addition to writing, he has also translated the work of Zadie Smith and Jonathan Safran Foer into Portuguese.

“A book of visceral and tender beauty whose echoes persist long after the final page.” – David Mitchell, author of The Bone Clocks

A coming of age tale of brutal beauty and disarming tenderness from one of Brazil’s most exciting young novelists, an author writing in the footsteps of “Roberto Bolaño, Jim Harrison, the Coen brothers and … Denis Johnson” (The New York Times)

The Shape of Bones

A Novel

By Daniel Galera

Translated by Alison Entrekin

Literary Fiction – Crime Mysteries

Hardcover

Aug 15, 2017

240 Pages

Publ. Penguin Random House

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News

A collection of seventeen wonderful short stories showing that two-time Oscar winner Tom Hanks is as talented a writer as he is an actor.

A gentle Eastern European immigrant arrives in New York City after his family and his life have been torn apart by his country’s civil war.

A gentle Eastern European immigrant arrives in New York City after his family and his life have been torn apart by his country’s civil war.

A man who loves to bowl rolls a perfect game – and then another and then another and then many more in a row until he winds up ESPN’s newest celebrity, and he must decide if the combination of perfection and celebrity has ruined the thing he loves.

An eccentric billionaire and his faithful executive assistant venture into America looking for acquisitions and discover a down and out motel, romance and a bit of real life.

These are just some of the tales Tom Hanks tells in this first collection of his short stories. They are surprising, intelligent, heart-warming, and, for the millions and millions of Tom Hanks fans, an absolute must-have.

Tom Hanks has been an actor, screenwriter, director and through Playtone, a producer. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair and The New Yorker. This is his first collection of fiction.

Publisher: Cornerstone

ISBN: 9781785151514

Number of pages: 416

Weight: 620 g

Dimensions: 222 x 144 x 38 mm

October 2017

Hardback

£13.99

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV

The haunting tale of a desolate cottage, and the hair-thin junction between this life and the next, from bestselling National Book Award finalist Gail Godwin.

After his mother’s death, eleven-year-old Marcus is sent to live on a small South Carolina island with his great aunt, a reclusive painter with a haunted past.

After his mother’s death, eleven-year-old Marcus is sent to live on a small South Carolina island with his great aunt, a reclusive painter with a haunted past.

Aunt Charlotte, otherwise a woman of few words, points out a ruined cottage, telling Marcus she had visited it regularly after she’d moved there thirty years ago because it matched the ruin of her own life.

Eventually she was inspired to take up painting so she could capture its utter desolation.

The islanders call it “Grief Cottage,” because a boy and his parents disappeared from it during a hurricane fifty years before. Their bodies were never found and the cottage has stood empty ever since. During his lonely hours while Aunt Charlotte is in her studio painting and keeping her demons at bay, Marcus visits the cottage daily, building up his courage by coming ever closer, even after the ghost of the boy who died seems to reveal himself.

Full of curiosity and open to the unfamiliar and uncanny given the recent upending of his life, he courts the ghost boy, never certain whether the ghost is friendly or follows some sinister agenda.

Grief Cottage is the best sort of ghost story, but it is far more than that–an investigation of grief, remorse, and the memories that haunt us. The power and beauty of this artful novel wash over the reader like the waves on a South Carolina beach.

Gail Godwin is a three-time National Book Award finalist and the bestselling author of twelve critically acclaimed novels, including Violet Clay, Father Melancholy’s Daughter, Evensong, The Good Husband and Evenings at Five. She is also the author of The Making of a Writer, her journal in two volumes (ed. Rob Neufeld). She has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts grants for both fiction and libretto writing, and the Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Gail Godwin lives in Woodstock, New York.

“Marcus’ fascination with the ghostly presence of an adolescent boy, thought to have perished at Grief Cottage in a hurricane, allows Godwin to explore themes of loss, connection, and growth unfettered by the corporeal world.” – Kirkus Reviews

Grief Cottage

A Novel

By: Gail Godwin

Published: 06-06-2017

Format: Hardback

Edition: 1st

Extent: 336

ISBN: 9781632867049

Imprint: Bloomsbury USA

Dimensions: 6 1/8″ x 9 1/4″

List price: $27.00

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News

Wat men doorgaans niet weet is dat Heyboer in de jaren 60 en 70 een gevierd kunstenaar was wiens werk werd aangekocht door het MoMA in New York, getoond op de Documenta in Kassel, en met grote tentoonstellingen werd geëerd in het Gemeentemuseum Den Haag en het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam.

In 1975 werd hij zelfs samen met David Hockney en Lucian Freud in LACMA in Los Angeles gepresenteerd als een van de belangrijkste Europese schilders van dat moment. Veertig jaar na zijn laatste grote museale tentoonstelling wil het Gemeentemuseum de internationale kwaliteit van zijn oeuvre opnieuw voor het voetlicht brengen.

In 1975 werd hij zelfs samen met David Hockney en Lucian Freud in LACMA in Los Angeles gepresenteerd als een van de belangrijkste Europese schilders van dat moment. Veertig jaar na zijn laatste grote museale tentoonstelling wil het Gemeentemuseum de internationale kwaliteit van zijn oeuvre opnieuw voor het voetlicht brengen.

De tentoonstelling toont de ontwikkeling van zijn oeuvre met de nadruk op de periode 1956-1977, maar belicht ook het ‘systeem’ waarmee de kunstenaar een manier vond om het leven voor zichzelf dragelijk te maken. Zo wordt duidelijk hoe het leven en werk van Heyboer onlosmakelijk met elkaar verbonden zijn.

Nog te zien t/m 04 februari 2018

Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Stadhouderslaan 41, 2517 HV Den Haag

Publicatie: Bij de tentoonstelling verschijnt een catalogus met teksten van onder meer Kees Keijer.

Anton Heyboer (Sabang, Indonesië, 1924 – Den Ilp, 2005) bekleedt een unieke positie binnen de moderne kunst. Met zijn mysterieuze, mystieke en hoogst persoonlijke beeldtaal plaatste hij zich in de jaren zestig en zeventig lijnrecht tegenover de toen heersende zakelijke kunststromingen zoals popart en minimal art.

In zijn etsen en tekeningen ontwikkelde Heyboer een ‘systeem’ om grip te krijgen op de demonen die hem sinds de Tweede Wereldoorlog achtervolgden, en om het leven voor zichzelf draaglijk te maken. Het is de kunst die zijn leven redt. Samen met zijn befaamde ‘vijf bruiden’ leefde Heyboer volgens de regels van zijn systeem, teruggetrokken in een zelfgebouwde, labyrintische woonruimte in Den Ilp. Hij creëerde zo zijn eigen, veilige universum waarin de kunst en zijn leven onlosmakelijk met elkaar verbonden zijn.

De kracht van Heyboers unieke werk bleef niet onopgemerkt. In de jaren zeventig werd Heyboer in één adem genoemd met kunstenaars als David Hockney en Lucian Freud en werd hij voorgedragen als een van Europa’s belangrijkste schilders van het moment. Hij maakte internationaal naam, maar vanaf 1975 trok hij zich volledig terug uit de kunstwereld en werd vooral zijn excentrieke leven een kolfje naar de hand van de roddelpers . Meer dan veertig jaar later brengt deze publicatie de internationale kwaliteit van zijn werk uit de jaren zestig en zeventig opnieuw voor het voetlicht.

Anton Heyboer

Het goede moment

Doede Hardeman, Hans Locher, Kees Keijer e.a

Uitgeverij Hannibal – Hannibal

Prijs: € 27,50

28,5 x 22 cm

192 bladzijden

Hardcover

Quadrichromie

Nederlandstalige editie

ISBN 978 94 9267 710 5

# Meer informatie website Haags Gemeentemuseum

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Dutch Landscapes, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, The Ideal Woman

De Pé Hawinkels Prijs is een nieuwe prijs voor makers en instanties die met creatieve initiatieven de grenzen van de literatuur oprekken.

Hawinkels (1942-1977) was iemand die zich niet in een hokje liet stoppen. Hij zorgde voor verbreding van de literatuur door zich bezig te houden met proza, poëzie, columns, jazzrecensies, vertalingen en zelfs songteksten (voor Herman Brood).

Welke schrijver, dichter, vertaler, journalist, filmmaker, uitgever, boekhandelaar droeg de afgelopen tijd met een bijzonder initiatief bij aan de verbreding van de literatuur? Dit kan zowel inhoudelijk als in vorm zijn, met bijvoorbeeld een app voor lezers, een politiek pamflet, een publiciteitsstunt of een project ten behoeve van verspreiding van boeken.

Vanaf nu kunt u een literair pionier nomineren. DAT KAN VIA DE WEBSITE VAN HET WINTERTUINFESTIVAL. Een vakkundige jury buigt zich over de genomineerden en kiest een winnaar. De prijs wordt op 25 november tijdens het Wintertuinfestival uitgereikt.

De Herfst van Hawinkels

De uitreiking van de Pé Hawinkels Prijs is een onderdeel van De Herfst van Hawinkels. In 2017 is het 40 jaar geleden dat Hawinkels overleed, hij zou anders dit jaar 75 zijn geworden. Dit najaar wordt het leven en werk van Hawinkels gevierd, onder meer met een expositie, een werkconferentie en een programma met jazz en voordrachten.

Wintertuin/De Nieuwe Oost is initiatiefnemer van de Pé Hawinkels Prijs en richt zich als productiehuis nadrukkelijk op ontwikkeling binnen het vakgebied. Met deze prijs wordt vernieuwing in de literatuur beloond en onder de aandacht gebracht.

# Meer info website wintertuinfestival

Nomineer een pionier voor de Pé Hawinkels Prijs

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Hawinkels, Pé, TRANSLATION ARCHIVE, Wintertuin Festival

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature