Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

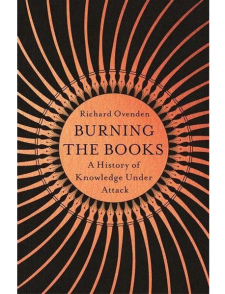

The director of the famed Bodleian Libraries at Oxford narrates the global history of the willful destruction―and surprising survival―of recorded knowledge over the past three millennia.

Libraries and archives have been attacked since ancient times but have been especially threatened in the modern era. Today the knowledge they safeguard faces purposeful destruction and willful neglect; deprived of funding, libraries are fighting for their very existence. Burning the Books recounts the history that brought us to this point.

Libraries and archives have been attacked since ancient times but have been especially threatened in the modern era. Today the knowledge they safeguard faces purposeful destruction and willful neglect; deprived of funding, libraries are fighting for their very existence. Burning the Books recounts the history that brought us to this point.

Richard Ovenden describes the deliberate destruction of knowledge held in libraries and archives from ancient Alexandria to contemporary Sarajevo, from smashed Assyrian tablets in Iraq to the destroyed immigration documents of the UK Windrush generation. He examines both the motivations for these acts―political, religious, and cultural―and the broader themes that shape this history. He also looks at attempts to prevent and mitigate attacks on knowledge, exploring the efforts of librarians and archivists to preserve information, often risking their own lives in the process.

More than simply repositories for knowledge, libraries and archives inspire and inform citizens. In preserving notions of statehood recorded in such historical documents as the Declaration of Independence, libraries support the state itself. By preserving records of citizenship and records of the rights of citizens as enshrined in legal documents such as the Magna Carta and the decisions of the US Supreme Court, they support the rule of law. In Burning the Books, Ovenden takes a polemical stance on the social and political importance of the conservation and protection of knowledge, challenging governments in particular, but also society as a whole, to improve public policy and funding for these essential institutions.

Richard Ovenden

Burning the books. A history of knowledge under attack

Publisher: Belknap Press

An Imprint of Harvard University Press

November 17, 2020

Language: English

Hardcover

320 pages

ISBN-10: 0674241207

ISBN-13: 978-0674241206

$29.95

Burning the Books is available internationally through the following publishers:

US: Harvard UP

German: Surhkamp

Italian: Solferino

Spanish: Editorial Critica

Arabic: Arab Scientific Publishers

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive O-P, Libraries in Literature

Little Red Riding-Hood

If you listen, children, I will tell

The story of little Red Riding-hood:

Such wonderful, wonderful things befell

Her and her grandmother, old and good

(So old she was never very well),

Who lived in a cottage in a wood.

Little Red Riding-hood, every day,

Whatever the weather, shine or storm,

To see her grandmother tripped away,

With a scarlet hood to keep her warm,

And a little mantle, soft and gay,

And a basket of goodies on her arm.

A pat of butter, and cakes of cheese,

Were stored in the napkin, nice and neat;

As she danced along beneath the trees,

As light as a shadow were her feet;

And she hummed such tunes as the bumble-bees

Hum when the clover-tops are sweet.

But an ugly wolf by chance espied

The child, and marked her for his prize.

“What are you carrying there?” he cried;

“Is it some fresh-baked cakes and pies?”

And he walked along close by her side,

And sniffed and rolled his hungry eyes.

“A basket of things for granny, it is,”

She answered brightly, without fear.

“Oh, I know her very well, sweet miss!

Two roads branch towards her cottage here;

You go that way, and I’ll go this.

See which will get there first, my dear!”

He fled to the cottage, swift and sly;

Rapped softly, with a dreadful grin.

“Who’s there?” asked granny. “Only I!”

Piping his voice up high and thin.

“Pull the string, and the latch will fly!”

Old granny said; and he went in.

He glared her over from foot to head;

In a second more the thing was done!

He gobbled her up, and merely said,

“She wasn’t a very tender one!”

And then he jumped into the bed,

And put her sack and night-cap on.

And he heard soft footsteps presently,

And then on the door a timid rap;

He knew Red Riding-hood was shy,

So he answered faintly to the tap:

“Pull the string and the latch will fly!”

She did: and granny, in her night-cap,

Lay covered almost up to her nose.

“Oh, granny dear!” she cried, “are you worse?”

“I’m all of a shiver, even to my toes!

Please won’t you be my little nurse,

And snug up tight here under the clothes?”

Red Riding-hood answered, “Yes,” of course.

Her innocent head on the pillow laid,

She spied great pricked-up, hairy ears,

And a fierce great mouth, wide open spread,

And green eyes, filled with wicked leers;

And all of a sudden she grew afraid;

Yet she softly asked, in spite of her fears:

“Oh, granny! what makes your ears so big?”

“To hear you with! to hear you with!”

“Oh, granny! what make your eyes so big?”

“To see you with! to see you with!”

“Oh, granny! what makes your teeth so big?”

“To eat you with! to eat you with!”

And he sprang to swallow her up alive;

But it chanced a woodman from the wood,

Hearing her shriek, rushed, with his knife,

And drenched the wolf in his own blood.

And in that way he saved the life

Of pretty little Red Riding-hood.

Hark, hark

The dogs do bark

Beggars are coming to town;

Some in jags,

Some in rags,

And some in velvet gowns.

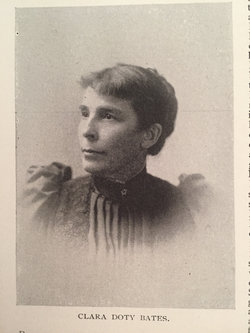

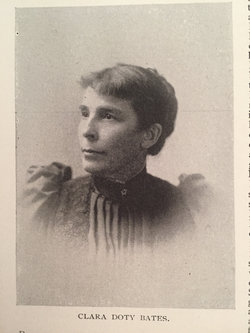

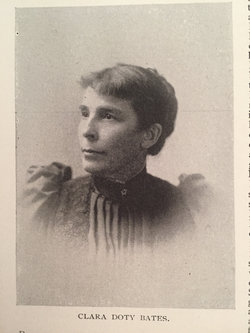

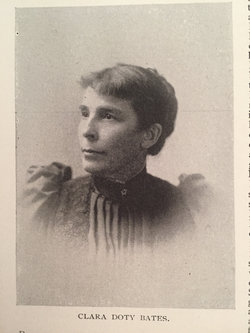

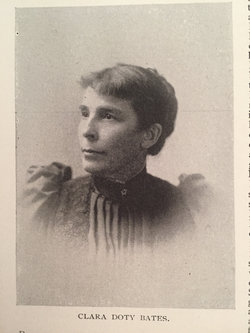

Clara Doty Bates

(1838 – 1895)

Little Red Riding-Hood

Versified by Mrs. Clara Doty Bates

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bates, Clara Doty, Children's Poetry, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

A Funeral Thought

I

When the stern Genius, to whose hollow tramp

Echo the startled chambers of the soul.

Waves his inverted torch o’er that pale camp

Where the archangel’s final trumpets roll,

I would not meet him in the chamber dim,

Hushed, and pervaded with a name-less fear,

When the breath flutters and the senses swim,

And the dread hour is near.

II

Though Love’s dear arms might clasp me fondly then

As if to keep the Summoner at bay,

And woman’s woe and the calm grief of men

Hallow at last the chill, unbreathing clay —

These are Earth’s fetters, and the soul would shrink,

Thus bound, from Darkness and the dread Unknown,

Stretching its arms from Death’s eternal brink,

Which it must dare alone.

III

But in the awful silence of the sky,

Upon some mountain summit, yet untrod,

Through the blue ether would I climb, to die

Afar from mortals and alone with God!

To the pure keeping of the stainless air

Would I resign my faint and fluttering breath,

And with the rapture of an answered prayer

Receive the kiss of Death.

IV

Then to the elements my frame would turn;

No worms should riot on my coffined clay,

But the cold limbs, from that sepulchral urn,

In the slow storms of ages waste away.

Loud winds and thunder’s diapason high

Should be my requiem through the coming time,

And the white summit, fading in the sky,

My monument sublime.

Bayard Taylor

(1825 – 1878)

A Funeral Thought

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Het graf van de lezer, Tales of Mystery & Imagination, Western Fiction

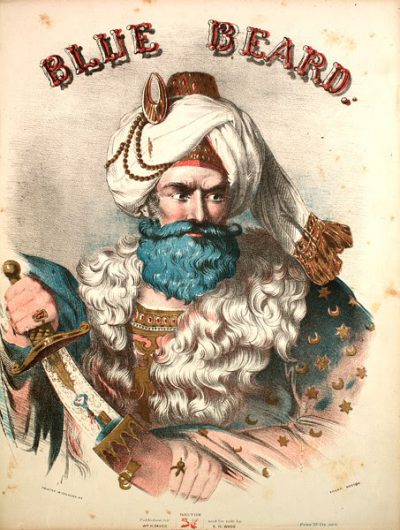

Blue Beard

Once on a time there was a man so hideous and ugly

That little children shrank and tried to hide when he appeared;

His eyes were fierce and prominent, his long hair stiff like bristles,

His stature was enormous, and he wore a long blue beard–

He took his name from that through all the country round about him,–

And whispered tales of dreadful deeds but helped to make him feared.

Yet he was rich, O! very rich; his home was in a castle,

Whose turrets darkened on the sky, so grand and black and bold

That like a thunder-cloud it looked upon the blue horizon.Blue Beard

He had fertile lands and parks and towns

and hunting-grounds and gold,

And tapestries a queen might covet, statues, pictures, jewels,

While his servants numbered hundreds,

and his wines were rare and old.

Now near to this old Blue-beard’s castle lived a lady neighbor,

Who had two daughters, beautiful as lilies on a stem;

And he asked that one of them be given him in marriage–

He did not care which one it was, but left the choice to them.

But, oh, the terror that they felt, their efforts to evade him,

With careless art, with coquetry, with wile and stratagem!

He saw their high young spirits scorned him, yet he meant to conquer.

He planned a visit for them,–or, ’twas rather one long fête;

And to charming guests and lovely feasts, to music and to dancing,

Swung wide upon its hinges grim the gloomy castle gate.

And, sure enough, before a week was ended, blinded, dazzled,

The youngest maiden whispered “yes,” and yielded to her fate.

And so she wedded Blue-beard–like a wise and wily spider

He had lured into his web the wished-for, silly little fly!

And, before the honeymoon was gone, one day he stood beside her,

And with oily words of sorrow, but with evil in his eye,

Said his business for a month or more would call him to a distance,

And he must leave her–sorry to–but then, she must not cry!

He bade her have her friends, as many as she liked, about her,

And handed her a jingling bunch of something, saying, “These

Will open vaults and cellars and the heavy iron boxes

Where all my gold and jewels are, or any door you please.

Go where you like, do what you will, one single thing excepted!”

And here he look a little key from out the bunch of keys.

“This will unlock the closet at the end of the long passage,

But that you must not enter! I forbid it!”–and he frowned.

So she promised that she would not, and he went upon his journey.

And no sooner was he gone than all her merry friends around

Came to visit her, and made the dim old corridors and chambers

With their silken dresses whisper, with laugh and song resound.

Up and down the oaken stairways flitted dainty-footed ladies,

Lighting up the shadowy twilight with the lustre of their bloom;

Like the varied sunlight streaming through an old cathedral window

Went their brightness glancing through the unaccustomed gloom,

But Blue-beard’s wife was restless, and a strong desire possessed her

Through it all to get a single peep at that forbidden room.

And so one day she slipped away from all her guests, unnoted,

Down through the lower passage, till she reached the fatal door,

Put in the key and turned the lock, and gently pushed it open–

But, oh the horrid sight that met her eyes! Upon the floor

There were blood-stains dark and dreadful,

and like dresses in a wardrobe,

There were women hung up by their hair, and dripping in their gore!

Then, at once, upon her mind the unknown fate that had befallen

The other wives of Blue-beard flashed–’twas now no mystery!

She started back as cold as icicles, as white as ashes,

And upon the clammy floor her trembling fingers dropped the key.

She caught it up, she whirled the bolt to, shut the sight behind her,

And like a startled deer at sound of hunter’s gun, fled she!

She reached her room with gasping breath,–behold, another terror!

Upon the key within her hand; she saw a ghastly stain;

She rubbed it with her handkerchief, she washed in soap and water,

She scoured it with sand and stone, but all was done in vain!

For when one side, by dint of work, grew bright, upon the other

(It was bewitched, you know,) came out that ugly spot again!

And then, unlooked-for, who should come

next morning, bright and early,

But old Blue-beard himself who hadn’t been away a week!

He kissed his wife, and, after a brief pause, said, smiling blandly:

“I’d like my keys, my dear.” He saw a tear upon her cheek,

And guessed the truth. She gave him all

but one. He scowled and grumbled:

“I want the key to the small room!”

Poor thing, she could not speak!

He saw at once the stain it bore while she turned pale and paler,

“You’ve been where I forbade you! Now you shall go there to stay!

Prepare yourself to die at once!” he cried. The frightened lady

Could only fall before him pleading: “Give me time to pray!”

Just fifteen minutes by the clock he granted. To her chamber

She fled, but stopped to call her sister Anne by the way.

“O, sister Anne, go to the tower and watch!” she cried, “Our brothers

Were coming here to-day, and I have got to die!

Oh, fly, and if you see them, wave a signal! Hasten! hasten!”

And Anne went flying like a bird up to the tower high.

“Oh, Anne, sister Anne, do you see anybody coming?”

Called the praying lady up the tower-stairs with piteous cry.

“Oh Anne, sister Anne, do you see anybody coming?”

“I see the burning sun,” she answered, “and the waving grass!”

Meanwhile old Blue-beard down below was whetting up his cutlass,

And shouting: “Come down quick, or I’ll come after you, my lass!”

“One little minute more to pray, one minute more!” she pleaded–

To hope how slow the minutes are, to dread how swift they pass!

“Oh Anne, sister Anne, do you see anybody coming?”

She answered: “Yes I see a cloud of dust that moves this way.”

“Is it our brothers, Anne?” implored the lady. “No, my sister,

It is a flock of sheep.” Here Blue-beard thundered out: “I say,

Come down or I’ll come after you!” Again the only answer:

“Oh, just one little minute more,–one minute more to pray!”

“Oh, Anne, sister Anne, do you see anybody coming?”

“I see two horsemen riding, but they yet are very far!”

She waved them with her handkerchief; it bade them, “hasten, hasten!”

Then Blue-beard stamped his foot so hard

it made the whole house jar;

And, rushing up to where his wife knelt, swung his glittering cutlass,

As Indians do a tomahawk, and shrieked: “How slow you are!”

Just then, without, was heard the beat of hoofs upon the pavement,

The doors flew back, the marble floors rang to a hurried tread.

Two horsemen, with their swords in hand,

came storming up the stairway,

And with one swoop of their good swords

they cut off Blue-beard’s head!

Down fell his cruel arm, the heavy cutlass falling with it,

And, instead of its old, ugly blue, his beard was bloody red!

Of course, the tyrant dead, his wife had all his vast possessions;

She gave her sister Anne a dower to marry where she would;

The brothers were rewarded with commissions in the army;

And as for Blue-beard’s wife, she did exactly as she should,–

She wore no weeds, she shed no tears; but very shortly after

Married a man as fair to look at as his heart was good.

Clara Doty Bates

(1838 – 1895)

Blue Beard

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bates, Clara Doty, Children's Poetry, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Cinderella

Poor, pretty little thing she was,

The sweetest-faced of girls,

With eyes as blue as larkspurs,

And a mass of tossing curls;

But her step-mother had for her

Only blows and bitter words,

While she thought her own two ugly crows,

The whitest of all birds.

She was the little household drudge,

And wore a cotton gown,

While the sisters, clad in silk and satin,

Flaunted through the town.

When her work was done, her only place

Was the chimney-corner bench.

For which one called her “Cinderella,”

The other, “Cinder-wench.”

But years went on, and Cinderella

Bloomed like a wild-wood rose,

In spite of all her kitchen-work,

And her common, dingy clothes;

While the two step-sisters, year by year,

Grew scrawnier and plainer;

Two peacocks, with their tails outspread,

Were never any vainer.

One day they got a note, a pink,

Sweet-scented, crested one,

Which was an invitation

To a ball, from the king’s son.

Oh, then poor Cinderella

Had to starch, and iron, and plait,

And run of errands, frill and crimp,

And ruffle, early and late.

And when the ball-night came at last,

She helped to paint their faces,

To lace their satin shoes, and deck

Them up with flowers and laces;

Then watched their coach roll grandly

Out of sight; and, after that,

She sat down by the chimney,

In the cinders, with the cat,

And sobbed as if her heart would break.

Hot tears were on her lashes,

Her little hands got black with soot,

Her feet begrimed with ashes,

When right before her, on the hearth,

She knew not how nor why,

A little odd old woman stood,

And said, “Why do you cry?”

“It is so very lonely here,”

Poor Cinderella said,

And sobbed again. The little odd

Old woman bobbed her head,

And laughed a merry kind of laugh,

And whispered, “Is that all?

Wouldn’t my little Cinderella

Like to go to the ball?

“Run to the garden, then, and fetch

A pumpkin, large and nice;

Go to the pantry shelf, and from

The mouse-traps get the mice;

Rats you will find in the rat-trap;

And, from the watering-pot,

Or from under the big, flat garden stone,

Six lizards must be got.”

Nimble as crickets in the grass

She ran, till it was done,

And then God-mother stretched her wand

And touched them every one.

The pumpkin changed into a coach,

Which glittered as it rolled,

And the mice became six horses,

With harnesses of gold.

One rat a herald was, to blow

A trumpet in advance,

And the first blast that he sounded

Made the horses plunge and prance;

And the lizards were made footmen,

Because they were so spry;

And the old rat-coachman on the box

Wore jeweled livery.

And then on Cinderella’s dress

The magic wand was laid,

And straight the dingy gown became

A glistening gold brocade.

The gems that shone upon her fingers

Nothing could surpass;

And on her dainty little feet

Were slippers made of glass.

“Be sure you get back here, my dear,

At twelve o’clock at night,”

Godmother said, and in a twinkling

She was out of sight.

When Cinderella reached the ball,

And entered at the door,

So beautiful a lady

None had ever seen before.

The Prince his admiration showed

In every word and glance;

He led her out to supper,

And he chose her for the dance;

But she kept in mind the warning

That her Godmother had given,

And left the ball, with all its charm.

At just half after eleven.

Next night there was another ball;

She helped her sisters twain

To pinch their waists, and curl their hair,

And paint their cheeks again.

Then came the fairy Godmother,

And, with her wand, once more

Arrayed her out in greater splendor

Even than before.

The coach and six, with gay outriders,

Bore her through the street,

And a crowd was gathered round to look,

The lady was so sweet,–

So light of heart, and face, and mien,

As happy children are;

And when her foot stepped down,

Her slipper twinkled like a star.

Again the Prince chose only her

For waltz or tete-a-tete;

So swift the minutes flew she did not

Dream it could be late,

But all at once, remembering

What her Godmother had said,

And hearing twelve begin to strike

Upon the clock, she fled.

Swift as a swallow on the wing

She darted, but, alas!

Dropped from one flying foot the tiny

Slipper made of glass;

But she got away, and well it was

She did, for in a trice

Her coach changed to a pumpkin,

And her horses became mice;

And back into the cinder dress

Was changed the gold brocade!

The prince secured the slipper,

And this proclamation made:

That the country should be searched,

And any lady, far or wide,

Who could get the slipper on her foot,

Should straightway be his bride.

So every lady tried it,

With her “Mys!” and “Ahs!” and “Ohs!”

And Cinderella’s sisters pared

Their heels, and pared their toes,–

But all in vain! Nobody’s foot

Was small enough for it,

Till Cinderella tried it,

And it was a perfect fit.

Then the royal heralds hardly

Knew what it was best to do,

When from out her tattered pocket

Forth she drew the other shoe,

While the eyelids on the larkspur eyes

Dropped down a snowy vail,

And the sisters turned from pale to red,

And then from red to pale,

And in hateful anger cried, and stormed,

And scolded, and all that,

And a courtier, without thinking,

Tittered out behind his hat.

For here was all the evidence

The Prince had asked, complete,

Two little slippers made of glass,

Fitting two little feet.

So the Prince, with all his retinue,

Came there to claim his wife;

And he promised he would love her

With devotion all his life.

At the marriage there was splendid

Music, dancing, wedding cake;

And he kept the slipper as a treasure

Ever, for her sake.

Clara Doty Bates

(1838 – 1895)

Cinderella

Versified by Mrs. Clara Doty Bates

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bates, Clara Doty, Children's Poetry, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

The Sleeping Princess

The ringing bells and the booming cannon

Proclaimed on a summer morn

That in the good king’s royal palace

A Princess had been born.

The towers flung out their brightest banners,

The ships their streamers gay,

And every one, from lord to peasant,

Made joyful holiday.

Great plans for feasting and merry-making

Were made by the happy king;

And, to bring good fortune, seven fairies

Were bid to the christening.

And for them the king had seven dishes

Made out of the best red gold,

Set thickly round on the sides and covers

With jewels of price untold.

When the day of the christening came, the bugles

Blew forth their shrillest notes;

Drums throbbed, and endless lines of soldiers

Filed past in scarlet coats.

And the fairies were there the king had bidden,

Bearing their gifts of good–

But right in the midst a strange old woman

Surly and scowling stood.

They knew her to be the old, old fairy,

All nose and eyes and ears,

Who had not peeped, till now, from her dungeon

For more than fifty years.

Angry she was to have been forgotten

Where others were guests, and to find

That neither a seat nor a dish at the banquet

To her had been assigned.

Now came the hour for the gift-bestowing;

And the fairy first in place

Touched with her wand the child and gave her

“Beauty of form and face!”

Fairy the second bade, “Be witty!”

The third said, “Never fail!”

The fourth, “Dance well!” and the fifth, “O Princess,

Sing like the nightingale!”

The sixth gave, “Joy in the heart forever!”

But before the seventh could speak,

The crooked, black old Dame came forward,

And, tapping the baby’s cheek,

“You shall prick your finger upon a spindle,

And die of it!” she cried.

All trembling were the lords and ladies,

And the king and queen beside.

But the seventh fairy interrupted,

“Do not tremble nor weep!

That cruel curse I can change and soften,

And instead of death give sleep!

“But the sleep, though I do my best and kindest,

Must last for an hundred years!”

On the king’s stern face was a dreadful pallor,

In the eyes of the queen were tears.

“Yet after the hundred years are vanished,”–

The fairy added beside,–

“A Prince of a noble line shall find her,

And take her for his bride.”

But the king, with a hope to change the future,

Proclaimed this law to be:

That, if in all the land there was kept one spindle,

Sure death was the penalty.

The Princess grew, from her very cradle

Lovely and witty and good;

And at last, in the course of years, had blossomed

Into full sweet maidenhood.

And one day, in her father’s summer palace,

As blithe as the very air,

She climbed to the top of the highest turret,

Over an old worn stair

And there in the dusky cobwebbed garret,

Where dimly the daylight shone,

A little, doleful, hunch-backed woman

Sat spinning all alone.

“O Goody,” she cried, “what are you doing?”

“Why, spinning, you little dunce!”

The Princess laughed: “‘Tis so very funny,

Pray let me try it once!”

With a careless touch, from the hand of Goody

She caught the half-spun thread,

And the fatal spindle pricked her finger!

Down fell she as if dead!

And Goody shrieking, the frightened courtiers

Climbed up the old worn stair

Only to find, in heavy slumber,

The Princess lying there.

They bore her down to a lofty chamber,

They robed her in her best,

And on a couch of gold and purple

They laid her for her rest,

The roses upon her cheek still blooming,

And the red still on her lips,

While the lids of her eyes, like night-shut lilies,

Were closed in white eclipse.

Then the fairy who strove her fate to alter

From the dismal doom of death,

Now that the vital hour impended,

Came hurrying in a breath.

And then about the slumbering palace

The fairy made up-spring

A wood so heavy and dense that never

Could enter a living thing.

And there for a century the Princess

Lay in a trance so deep

That neither the roar of winds nor thunder

Could rouse her from her sleep.

Then at last one day, past the long-enchanted

Old wood, rode a new king’s son,

Who, catching a glimpse of a royal turret

Above the forest dun

Felt in his heart a strange wish for exploring

The thorny and briery place,

And, lo, a path through the deepest thicket

Opened before his face!

On, on he went, till he spied a terrace,

And further a sleeping guard,

And rows of soldiers upon their carbines

Leaning, and snoring hard.

Up the broad steps! The doors swung backward!

The wide halls heard no tread!

But a lofty chamber, opening, showed him

A gold and purple bed.

And there in her beauty, warm and glowing,

The enchanted Princess lay!

While only a word from his lips was needed

To drive her sleep away.

He spoke the word, and the spell was scattered,

The enchantment broken through!

The lady woke. “Dear Prince,” she murmured,

“How long I have waited for you!”

Then at once the whole great slumbering palace

Was wakened and all astir;

Yet the Prince, in joy at the Sleeping Beauty,

Could only look at her.

She was the bride who for years an hundred

Had waited for him to come,

And now that the hour was here to claim her,

Should eyes or tongue be dumb?

The Princess blushed at his royal wooing,

Bowed “yes” with her lovely head,

And the chaplain, yawning, but very lively,

Came in and they were wed!

But about the dress of the happy Princess,

I have my woman’s fears–

It must have grown somewhat old-fashioned

In the course of so many years!

Clara Doty Bates

(1838 – 1895)

The Sleeping Princess

Versified by Mrs. Clara Doty Bates

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bates, Clara Doty, Children's Poetry, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Jack And Jill

Little boys, sit still–

Girls, too, if you will–

And let me tell you of Jack and Jill;

For I think another

Such sister and brother

Were never the children of one mother!

For an idle lad,

As he was, Jack had

No traits, after all, that were very bad.

He, was simply Jack,

With the coat on his back

Patched up in all colors from gray to black.

Both feet were bare;

And I do declare

That he never washed his face; and his hair

Was the color of straw–

You never saw

Such a crop–as long as the moral law!

When he went to school,

It was the rule

(Though ’twas hard to say he was really a fool)

To send him at once,

So thick was his sconce,

To the block that was kept for the greatest dunce.

And Jill! no lass

Scarce ever has

Made bigger tracks on the country grass;

For her only fun

Was to romp and run,

Bare-headed, bare-footed, in wind and sun.

Wherever went Jack,

Close on his track,

With hair unbraided and down her back,

Loud-voiced and shrill,

She followed, until

No one said “Jack” without saying “Jill.”

But to succeed

In teaching to read

Such a harum-scarum, was work indeed!

And I’m forced to tell

That her way to spell

Her name was with only a single ‘l.’

Yet they were content.

One day they were sent

To the hill for water, and they went.

They did not drown,

But Jack fell down,

With a pail in his hand, and broke his crown!

And Jill, who must go

And always do

Exactly as Jack did, tumbled too!

Just think, if you will,

How they rolled down hill–

Straw-headed Jack and bare-footed Jill!

But up Jack got,

And home did trot,

Nor cared whether Jill was hurt or not;

While his poor bruised knob

Did burn and throb,

Tear falling on tear, sob following sob!

He could run the faster,

So a paper plaster

Had bound up the sight of his disaster

Before Jill came;

And the thoughtful dame,

For a break in her head, had fixed the same.

But Jill came in,

With a saucy grin

At seeing the plight poor Jack was in;

And when she saw

That bundle of straw

(His hair) bound up with a cloth, and his jaw

Tied up in white,

The comical sight

Made her clap her hands and laugh outright!

The dame, perplexed

And dreadfully vexed,

Got a stick and said, “I’ll whip her next!”

How many blows fell

I will not tell,

But she did it in earnest, she did it well,

Till the naughty back

Was blue and black,

And Jill needed a plaster as much as Jack!

The next time, though,

Jack has to go

To the hill for water, I almost know

That bothering Jill

Will go up the hill,

And if he falls again, why, of course she will!

Clara Doty Bates

(1838 – 1895)

Jack And Jill

Versified by Mrs. Clara Doty Bates

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bates, Clara Doty, Children's Poetry, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

To Tirzah

Whate’er is born of mortal birth

Must be consumed with the earth,

To rise from generation free:

Then what have I to do with thee?

The sexes sprang from shame and pride,

Blown in the morn, in evening died;

But mercy changed death into sleep;

The sexes rose to work and weep.

Thou, mother of my mortal part,

With cruelty didst mould my heart,

And with false self-deceiving tears

Didst bind my nostrils, eyes, and ears,

Didst close my tongue in senseless clay,

And me to mortal life betray.

The death of Jesus set me free:

Then what have I to do with thee?

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

To Tirzah

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Grabgesang

Vor des Friedhofs dunkler Pforte

Bleiben Leid und Schmerzen stehn,

Dringen nicht zum heil’gen Orte,

Wo die sel’gen Geister gehn,

Wo nach heißer Tage Glut

Unser Freund in Frieden ruht.

Zu des Himmels Wolkentoren

Schwang die Seele sich hinan,

Fern von Schmerzen, neu geboren,

Geht sie auf — die Sternenbahn;

Auch vor jenen heil’gen Höhn

Bleiben Leid und Schmerzen stehn.

Sehnsucht gießet ihre Zähren

Auf den Hügel, wo er ruht;

Doch ein Hauch aus jenen Sphären

Füllt das Herz mit neuem Mut;

Nicht zur Gruft hinab — hinan,

Aufwärts ging des Freundes Bahn.

Drum auf des Gesanges Schwingen

Steigen wir zu ihm empor,

Unsre Trauertöne dringen

Aufwärts zu der Sel’gen Chor,

Tragen ihm in stille Ruh’

Unsre letzten Grüße zu.

Wilhelm Hauff

(1802 – 1827)

Grabgesang, Gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Galerie des Morts, Hauff, Hauff, Wilhelm, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Maria Janitschek

Das neue Weib

Frau Selma Knolle liebte die Einsamkeit und schwärmte vom völligen Abgeschlossensein von der Welt. Deshalb veranstaltete sie jede Woche einen Empfangsabend, an dem sich über ein halbes Hundert Menschen in ihrem Hause zusammenfanden. Sie betete die Wahrheit an, und ihre Busenfreundin war eine – Spiritistin; sie stellte die höchsten Anforderungen an die Sittenreinheit des Weibes, und ihre Abgötterei galt einer vierzigjährigen Dame, die noch vor Thorschluss das Jungfernkränzchen abgelegt hatte, um die interessanten Umstände kennen zu lernen.

Frau Selma Knolle hatte als Mädchen immer für das Cölibat geschwärmt, deshalb heiratete sie einen athletisch gebauten Mann, der schon von zwei Gattinnen geschieden war. Sie bekam vier Kinder von ihm. Er war ein verteufelt schlauer Bursche, der Doktor. Dem Zug seiner Zeit folgend, hatte er viele Reisen gemacht, sechsmal seinen Beruf gewechselt, sein Vermögen verloren, wieder erworben, abermals verloren, sich durch gute Partien wieder rangiert, aber, zu vielseitig begabt für einen Ehemann, schlechten Erfolg mit seinen Gattinnen gehabt. Zum Schluss war ihm diese grosse, blonde Frau mit dem weichen Fleisch begegnet, die ihm resolut sagte:

Frau Selma Knolle hatte als Mädchen immer für das Cölibat geschwärmt, deshalb heiratete sie einen athletisch gebauten Mann, der schon von zwei Gattinnen geschieden war. Sie bekam vier Kinder von ihm. Er war ein verteufelt schlauer Bursche, der Doktor. Dem Zug seiner Zeit folgend, hatte er viele Reisen gemacht, sechsmal seinen Beruf gewechselt, sein Vermögen verloren, wieder erworben, abermals verloren, sich durch gute Partien wieder rangiert, aber, zu vielseitig begabt für einen Ehemann, schlechten Erfolg mit seinen Gattinnen gehabt. Zum Schluss war ihm diese grosse, blonde Frau mit dem weichen Fleisch begegnet, die ihm resolut sagte:

»Deine andern Gattinnen verstanden dich nicht, ich aber verstehe dich und bin die Richtige für dich.« Da hatte er zum drittenmal eingewilligt, einer schönen Frau zu einem Irrtum zu verhelfen. In den ersten vier Jahren war sie beständig schwanger und konnte sich seiner nicht so erfreuen, wie sie es gewünscht hätte. Dann musste er – er behauptete es wenigstens – eine Reise um die Welt machen. Als er wiederkehrte, hatte er allerlei Marotten mitgebracht.

Er zog z.B. ihre langen Nachthemden an und setzte sich in diesem Aufzug in ein künstlich verdunkeltes Zimmer, um »nachzudenken«. Er behauptete, dann erhabene Gesichte zu haben, die er nach seinem Tod aufzeichnen wollte. Manchmal verschmähte er sogar ihre Nachthemden und sie fand ihn als Adam verkleidet. Schliesslich fing sie an, an seinem Verstand zu zweifeln und eilte, einen Nervenarzt zu holen. Der blieb sehr lange bei Knolle, und als er dessen Zimmer verliess, machte er ein sehr vergnügliches Gesicht, drückte ihr beruhigend die Hand, erkundigte sich teilnahmsvoll nach ihrem Gesundheitszustand und verschrieb ihr Pillen. Sie verstand das alles sich zwar nicht zusammenzureimen, doch war sie zufrieden, dass ihrem Bibibi, wie sie den Athleten nannte, nichts Ernsthaftes fehle. Sie überlegte, zu welchem Beruf sie ihm raten sollte.

Und da sie im Grunde doch an seinem gesunden Verstand zweifelte, kaufte sie ihm eine Zeitung, deren Leitung er zugleich übernehmen sollte.

Sie kalkulierte ganz richtig, dass es für einen Mann von seiner Begabung keine passendere Beschäftigung geben konnte. Bibibi, der Bibibi, der drei strenge Jungfrauen zum Altar geführt hatte – nicht alle seine Jungfrauen hatte er zum Altar geführt! -, kehrte glücklich das Unterste seiner Überzeugungen nach oben. Er nahm nur Ehebruchsromane für seine Zeitung an und lehnte kaltblütig alle andern litterarischen Anerbieten ab. Der Ehebruch musste natürlich in einer verdeckten Schüssel und mit Gewürz aus den Beeten der Romantik serviert sein. Ferner nahm er nur von Damen Arbeiten an. Diese Damen durften indes nicht das vierundzwanzigste Jahr überschritten haben, um noch »ihre ganze Frische« dem Publikum bieten zu können. Zum Schluss pflegte er mit jeder Verfasserin, von der er eine Arbeit acceptierte, die letzten Abmachungen in einem Hotel zu treffen, »weil er da ungestörter sei, als in den unruhigen Redaktionsräumen.«

Sein Lesekomitee, d.h. die jede eingelaufene Arbeit Prüfenden, bestand aus ihm geistig verwandten Weibern in Männerröcken. Daneben hatte er unter andern Kritikern besonders zwei engagiert, die einer gewissen Berühmtheit genossen. Der eine machte alles nieder, was er las, der andere war ein Genie; der machte sogar das nieder, was er nicht gelesen hatte.

Und der Verleger gedieh und die Mitarbeiter gediehen und die Zeitung gedieh. Bibibi machte einen Ableger von ihr und gründete eine kleine illustrierte Zeitschrift. Das Genie schimpfte diese neue Zeitschrift in Grund und Boden nieder, so dass Bibibi sofort eine zweite, die besser sein sollte, erscheinen liess. Die Schimpferei war natürlich nur ein Trick gewesen, um zwei neuen Zeitschriften zum Dasein zu verhelfen. Bibibi war eben ein grosser Schlaukopf und wusste genau, wie man das Zeug anfasste. Frau Selma schwamm in Wonne. Sie erkannte jetzt, dass ihres Mannes anscheinende Verrücktheit nur Schlauheit war. Sowie er sich auf den richtigen Platz gestellt sah, waren alle in ihm schlummernden Fähigkeiten erwacht.

Er schmeichelte der verkappten Lüsternheit des Publikums und gab ihr fette Bissen, aber nur von der langen Sauce scheinheiliger Frömmelei begossen. Ohne diese nie, denn er war sehr für die Moral seiner Leser besorgt. Man sündigte hier nur in verdunkelten Ecken. Die Sonne durfte es nicht sehen. Nackt zu gehen war verboten, die Röckchen zu lüpfen erlaubt. Wo sich in einem Roman eine Gestalt fand, die gegen Anfechtungen kämpfte, wurde der Roman zurückgewiesen. Anständige, d.h. kluge Leute haben keine Anfechtungen, entschied der Chefredakteur; denn wenn sie solche haben, kommt es nicht an den Tag. Wird aber ein Mensch mit Anfechtungen geschildert, so muss er gleich als niederträchtiger Kerl hingestellt werden. Frau Selma und das Publikum glaubten an die strenge Moral des grossen Bibibi. Nur eins konnte Selma nicht recht verstehen: diese Kontraktabschlüsse im Hotel.

Einmal brachte sie es durch Schlauheit und Thürenhorcherei dahin, in Erfahrung zu bringen, wann er seine nächsten Abmachungen mit einem neuen litterarischen Stern im Hotel haben würde. Eine Stunde vorher fuhr sie dicht verschleiert, eine Handtasche tragend, dahin und liess sich die Stube neben dem vereinbarten Zimmer geben. Nach einer geraumen Zeit hörte sie endlich die beiden eintreten. Sie vernahm Bibibis Stimme und eine schüchterne zweite, die der Frau A.B., einer jung verheirateten Dame, angehörte.

Selma legte hochaufhorchend das Ohr an die Thür. Zuerst hörte sie nur ein vergnügliches Grunzen, wie Bibibi von sich gab, wenn er glücklich küsste. Dann kamen wohlbekannte Laute, so wie sie zu Anfang ihrer Ehe ihr selbst entflohen waren, wenn Bibibi gar zu stürmisch zu seinem Recht gelangen wollte. Dann verriet das Knarren einer indiskreten Bettstatt allerlei, was Selma besser verborgen geblieben wäre. Dann folgte die feierliche Stille nach dem Sturm.

Selma hatte sich behutsam auf den Boden niedergelassen, denn das Stehen wurde ihr unbequem. Später hörte sie eine pipsende Stimme jammern: »O Gott, mein armer Mann, mein armer Mann! Was wird er bloss sagen, wenn das Essen um Eins nicht fertig ist; o ich muss nach Hause!« …

Man hörte allerlei rauschen, dann Wassergeriesel, dann flüsterte Bibibi: »Lass mich zuerst hinab, Kindchen, ich mache alles beim Portier ab, ich habe fürchterliche Eile. Die Fahnen müssen um 12 Uhr nach der Druckerei und jetzt ist’s dreiviertel auf Zwölf. Den Kontrakt erhältst du morgen. Der Roman erscheint in sechs Wochen, wir bringen dein Vollbild und du bekommst dreitausend Mark Honorar für den Erstabdruck. Hab vielen Dank, mein Herz. Das nächste Mal machen wir’s mit mehr Musse. Adieu!«

Frau Selma erhob sich von ihrem Lauscherposten. War das ein Rückfall in seine Verrücktheit gewesen? Gewiss, nur das konnte es sein! Sie sah ihn grübelnd, forschend beim Mittagessen an und gab ihm drei Abende hindurch keinen[204] Gutenachtkuss. Aber sie horchte von nun an viel an der Thür, die in das Redaktionszimmer führte, in dem er allein arbeitete.

Sie brachte allerlei in Erfahrung. Wie Schriftstellerinnen oft zu ihrem Ruhm kamen. Wie andere abgewiesen wurden, weil sie bei gewissen Zumutungen hochmütig aufgefahren waren. Weshalb die Belletristik das fast ausschliesslich vom Weibe beherrschte Gebiet geworden war. Wie dem Publikum eine Geschmacksrichtung aufgedrängt wurde, die nur von der jeweiligen Appetitsverschiedenheit des Chefredakteurs abhing. Wie die Guillotine der Kritik ohne Hirn und Vernunft arbeitete. Wie immer weniger ernsthafte Männer auf dem schöngeistigen Arbeitsfeld mitkämpfen wollten …

Sie verwunderte sich über manches, aber sie war zu sehr Weib, um ihre persönliche Sache nicht als Hauptsache zu empfinden. Sie horchte weiter und sie vernahm noch verschiedene »Vereinbarungen«. Nur um ihr schlecht wiedergegebenes Bild in eine Tageszeitung zu lancieren, ergaben sich manche dieser jungen Frauen den Launen Bibibis.

Nein, Bibibi, kein Verrückter bist du, eine menschliche Bestie bist du, schluchzte die arme Frau Selma im Nebenzimmer. Aber warte, ich will mich an dir rächen, dass du wirklich verrückt werden sollst. Vor allem dafür, dass du mich in Bezug auf deine eheliche Treue irre geführt hast. Oder hast du mich überhaupt nie an sie glauben machen wollen und – ich selbst habe mich im Glauben an sie bestärkt? Dann sollst du es doppelt büssen, denn was man selbst Dummes begeht, daran ist immer der andere schuld … Und Selma, bis zum Rand mit Wut und Erbitterung gefüllt, vergass ihren Stolz, stellte sich mit anderm weiblichen Federvieh auf eine Stufe und schrieb ein Buch. Sie nannte es: »Das seid Ihr!« Schon das erste Wort, mit dem wir empfangen werden, begann sie, ist ein geringschätziges. Nur ein Mädchen! Oder heisst es in den meisten Fällen nicht so, wenn die sage femme uns in die Arme des Vaters legt? Dann später werden wir von unsern uns an Kraft überlegenen Brüdern gefoppt, übervorteilt, misshandelt. Die öden Jahre der Bleichsucht beginnen. Unlustig, von einem Gefühl der Dumpfheit und Schwere gequält, schleppen wir uns dahin, bis ein Tag uns das mit mancherlei körperlichen Leiden erkaufte Siegel aufdrückt, dass wir nun zum Gebären reif sind. Haben wir Geld und ein hübsches Gesicht, so ist bald der Freier da, der um uns wirbt. Nach einer unnatürlich verlebten Verlobungszeit, in der wir unser erwachendes Temperament verleugnen und Komödie spielen müssen, werden wir endlich zum Traualtar geführt. Die heimlich tausendmal ersehnte Hochzeitsnacht ist da. Anstatt der werbenden Zärtlichkeit des Geliebten zu begegnen, werden wir von einem keuchenden, brünstigen Gewalthaber genotzüchtigt, der vom Priester und unsern Eltern das Recht dazu empfangen hat. Nach Schmerzen und Demütigungen mancherlei Art werden wir endlich schwanger. Fast ein Jahr widriger Verunstaltung, widriger Krankheitszustände, dann kommt die Stunde, wo unserer Schamhaftigkeit der letzte Schleier entrissen wird. Nackt wie ein Tier, in Bewusstlosigkeit versetzt, oder im Krampf verzerrt, ruhen wir hilflos vor den Augen eines fremden Mannes, des Arztes, der oft noch Kollegen an der Seite hat. Man wühlt in unserm Körper, verspritzt unser Blut und legt sorgsam Verbände und Salben zurück fürs »nächste« Mal. Noch kaum von unsern Wunden geheilt, findet uns die neu aufflammende Gier des Mannes, zu der sich vielleicht noch der Kitzel der Grausamkeit gesellt. Nach elf Monaten machen wir die Schlachtscene aufs neue durch. Und so weiter. Eines Tages aber harren wir vergebens der Liebkosungen unseres Gatten. Er ist unserer satt geworden. Die Liebeskunststücke, die er uns gelehrt hat, besitzen keinen Reiz mehr für ihn. Nun geht er zu andern Frauen, um neue einzuüben. Aber die können wir nicht mehr erlernen, denn unser Körper, von ihm gebrochen und zerstört, hat keine Kraft mehr in seinen Muskeln. Wir sind schlaff geworden. Wenn er ehrlich ist, sagt er uns die Wahrheit mit offenem Visier; wenn er feig ist, betrügt er uns hinter unserm Rücken …

Und nun begann die feurige Anklage gegen den einen. Das ganze Buch war so persönlich gehalten, dass jeder sofort wusste, Bibibi sei hier in die Hände einer Überlegnen geraten, die ihn durchschaute. Die Frauen alle, die geknechteten, geopferten, misshandelten, umringten ihre mutige Schwester, das neue Weib, die erste, die es gewagt hatte, ihren Tyrannen offen an den Pranger zu stellen. Sie drückten ihr die Hände, wenn sie sie auf der Strasse trafen, sie schrieben ihr danküberströmende Briefe.

Sie war mit einem Male die Heldin der unterdrückteren Hälfte der Menschheit geworden. Man war aufs höchste darauf gespannt, wie sie nun ihre edlen revolutionären Ideen in Thaten umsetzen würde; denn nach diesem unerhörten Buch musste sie mit einem verächtlichen Fahrwohl von ihm, dem Knechter ihrer Individualität und Frauenwürde, scheiden. Einsame Arbeit in stolzer Unabhängigkeit würde ihr Märtyrerlos worden. Man bereitete sich vor, ihre Apotheose zu erleben.

Bibibi machte ein langes und immer längeres Gesicht. Alle Wetter! War er trotz aller Vorsichtsmassregeln doch noch zu unvorsichtig gewesen? Hatte sie Verdacht geschöpft? Hatte ihn eine seiner Freundinnen verraten? Ihm, dem Verfechter der öffentlichen Moral, war die Sache höchst unangenehm. Hauptsächlich jedoch deshalb, weil er sich als – unschlau erwiesen hatte. Wer wollte nicht lieber für einen Schurken als für einen dummen Kerl gelten? Nun, er hatte jetzt festen Boden unter seinen Füssen, mochte sie ihn schliesslich verlassen. Er liess doppelt empörte Tiraden gegen alle los, die einen Schritt vom Wege der breiten, fetten Moral thaten. Ja, er begann sich gegen das Weib zu wenden, dem die heiligsten Bande nicht zu ehrwürdig wären, um mit ihnen sein Spiel zu treiben. Er hing nicht so sehr an Selma, um eine Trennung von ihr als zu schweren Schicksalsschlag zu empfinden, aber den Skandal hasste er.

Seit sie wusste, dass er ihr Buch gelesen hatte, und das ungeheure Aufsehen ermass, das es erregte, ging sie ihm scheu aus dem Wege. Sie kannte seine herkulischen Kräfte, dazu seine Gereiztheit; wer weiss, was geschah. Auch ihre Bekannten dachten ähnlich und sahen sie schon als Opfer ihres Mutes, als Märtyrerin ihrer Ideen. Man erwartete bang die letzte Katastrophe.

Es gab Journalistinnen, die schon einen Nekrolog für sie im Pult bereit liegen hatten.

Da kam das, was die Wenigsten vorausgesetzt hatten …

Eines Abends, als sie von einem Gang heimkam, trat ihr Bibibi in den Weg.

»Magst du einen Augenblick bei mir eintreten?« fragte er mit eisiger Höflichkeit. Sie folgte ihm und blieb mit schlotternden Knieen an der Thür stehen. Er schritt gleichmütig auf und nieder.

»Ich habe also den Scheidungsprozess eingeleitet,« log er, »denn nach deinem persönlichen Angriff auf mich durfte ich unmöglich anders handeln. Ich ersuche dich nun, die Kinder so schonend wie möglich auf die Sache vorzubereiten. Das Gericht wird entscheiden, ob sie vater- oder mutterlos ihr junges Leben weiterführen sollen. Was mich betrifft, ich bin ein Mann der Arbeit, der Thätigkeit, mein Beruf wird mich über mein -,« er stockte, »über mein unverdientes Schicksal erheben. Und wenn -,« er stockte wieder, »wenn ich es nicht ertragen sollte, dann –«

In diesem Augenblick nahm die alte Eva, die alte Eva, die niemals auch aus dem »neuesten« Weibe auszutreiben ist, wieder Besitz von Frau Selma. Sie sank auf die Kniee und ergriff die Hände ihres Gatten.

»Bibibi, kannst du mir das Buch verzeihen?«

Er verstand sofort die Situation, die er als Menschenkenner vorausgeahnt hatte, und richtete sich auf.

»Nein!«

»Bibibi, bedenke, welche Qualen du mir verursacht hast; ich war toll geworden, ich sehe es jetzt ein, aber – verraten hast du mich doch, das kannst du nicht leugnen, denn ich war Zeugin.«

»Horcherin!« Er stiess sie verächtlich von sich und that einige Schritte.

Sie rutschte ihm auf den Knieen nach.

»Bibibi, schlage mich, aber verstosse mich nicht; ich liebe dich, auch wenn du mich mit Füssen trittst, mir andere vorziehst; lass mich nur neben dir sein, die letzte, die allerletzte, nur neben dir! Dir habe ich meine Kinder geboren, meine Jugend hingegeben, ich kann ja nicht von dir fort, verzeih mir …!«

Und Bibibi blickte auf sie herab. Das war also das neue Weib. Was war nun eigentlich das neue an ihm? War es mehr als seine gesteigerte – Redseligkeit, die sich in anklagenden Romanen, stürmischen Versammlungen, kampflustigen Vorträgen offenbarte? Er furchte die Stirne und hiess grossmütig Selma aufstehen …

Bei sich aber beschloss er, noch gründlichere Frauenstudien zu treiben …

More in: Archive I-J, Archive I-J, The Ideal Woman

Ein modernes Weib

Ein Mann beleidigte ein Weib. Es war

Von jenen schnöden Thaten eine, die

Kein Weib vergessen und vergeben kann.

Geraume Zeit verstrich. Da eines Abends

Ward an die Thür des Frevlers laut gepocht.

Er rief: “Herein”, und sah voll tiefen Staunens,

In Trauerkleidern eine Frau vor sich.

Sie schlug den Schleier bald zurück. Er blickte

In ihre großen stolzerstarrten Augen,

In diese großen schmerzversengten Augen …

Er lächelte verlegen, denn ein Schauer

Erfaßte ihn … Er bot ihr höflich Platz,

Sie aber dankte, und mit ruhiger Stimme

Sprach sie zu ihm: “Du hast mich schwer beleidigt,

Es war nur Gott dabei … vor diesem Gott,

Vor dir, und mir allein, will ich den Flecken

Den Makel meiner Ehre, zugefügt

Von deiner Hand, verlöschen.

Höre nun!

Um dies zu thun, bleibt mir ein Mittel nur:

Ich kann nicht gehn, um einem fremden Menschen

Das was ich selbst mir kaum zu sagen wage,

Zu offenbaren. Für mich herrscht kein Richter,

Er wär′ denn blind und taub und stumm, deshalb

(Ein Schildern des Vergangenen glich′ aufs Haar

Der neuen That, hieß′ selber mich entehren),

Deshalb gibt′s eins nur: hier sind Waffen, wähle!”

Sie stellte auf den Tisch ein Kästchen hin

Und öffnete den Deckel. – –

Lange standen

Die beiden Menschen stumm. Er sah sie an,

Sie hielt das glänzend große Aug′ gerichtet

Fest auf die Waffen.

Plötzlich brach er aus

In lautes Lachen. Da durchglühte feurig

Ein tiefes Rot die farbenlosen Wangen

Der jungen Frau. Wie, wenn die ganze Antwort

Dies Lachen wär′? Sie hätte schreien mögen

Vor Wut und Elend. Aber sie bezwang sich,

Und sagte mild: “Wenn dir ein Unvorsichtiger

Zufällig auf den Fuß getreten wäre,

Du würdest ohne lange Ueberlegung

Ihm deine Karte in das Antlitz schleudern,

Nichts Lächerliches fändest du dabei.

Nun denk′: nicht auf den Fuß trat mir ein Mensch,

Mein Herz trat er in Stücke, meine Ehre!

Verlang′ ich mehr, als du verlangen würdest

Für einen unvorsichtigen Schritt, sag′ selbst,

Ist das nicht billig?”

Lächelnd sah er ih

Ins zornerglühte Antlitz. “Liebes Kind,

Du scheinst es zu vergessen, daß ein Weib

Sich nimmer schlagen kann mit einem Manne.

Entweder geh zum Richter, liebes Kind,

Gesteh ihm alles, gerne unterwerfe

Ich seinem Urteil mich. Nicht? Nun dann bleibt

Dir nur das eine noch: vergesse, was du

Beleidigung und Schmach nennst. Siehst du, Liebe,

Das Weib ist da zum Dulden und Vergeben …”

Jetzt lachte sie.

“Entweder Selbstentehrung

Wenn nicht, ein ruhiges Tragen seiner Schmach,

Und das, das ist die Antwort, die ein Mann

In unserer hellen Zeit zu geben wagt

Der Frau, die er beleidigt.”

“Eine andere

Wär′ gegen den Brauch.”

“So wisse, daß das Weib

Gewachsen ist im neunzehnten Jahrhundert,”

Sprach sie mit großem Aug′, und schoß ihn nieder.

Maria Janitschek

(1859 – 1927)

Gedicht

Ein modernes Weib

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Archive I-J, CLASSIC POETRY, The Ideal Woman

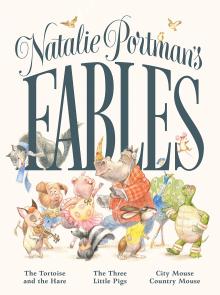

Academy Award-winning actress, director, producer, and activist Natalie Portman retells three classic fables and imbues them with wit and wisdom.

From realizing that there is no “right” way to live to respecting our planet and learning what really makes someone a winner, the messages at the heart of Natalie Portman’s Fables are modern takes on timeless life lessons.

From realizing that there is no “right” way to live to respecting our planet and learning what really makes someone a winner, the messages at the heart of Natalie Portman’s Fables are modern takes on timeless life lessons.

Told with a playful, kid-friendly voice and perfectly paired with Janna Mattia’s charming artwork, Portman’s insightful retellings of The Tortoise and the Hare, The Three Little Pigs, and Country Mouse and City Mouse are ideal for reading aloud and are sure to become beloved additions to family libraries.

Natalie Portman is an Academy Award-winning actress, director, producer, and activist whose credits include Leon: The Professional, Cold Mountain, Closer, V for Vendetta, the Star Wars franchise prequels, A Tale of Love and Darkness, Jackie, and Thor: Love and Thunder. Born in Jerusalem, Israel, she is a graduate of Harvard University, and now lives with her family in Los Angeles. Natalie Portman’s Fables is her debut picture book.

Janna Mattia was born and raised in San Diego. She received a degree in Illustration for Entertainment from Laguna College of Art and Design, and now works on concept and character art for film, illustration for licensing, and private commissions. Natalie Portman’s Fables is her picture book debut.

Natalie Portman’s Fables

Natalie Portman (Author)

Janna Mattia (Illustrator)

Age Range: 4 – 6 years

Hardcover: 64 pages

Publisher: Feiwel & Friends (October 20, 2020)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1250246865

ISBN-13: 978-1250246868

$17.99

# new books

Natalie Portman’s Fables

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive O-P, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature