Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Beauty abounds in Jericho Brown’s Pulitzer Prize-winning poetry collection, despite and inside of the evil that pollutes the everyday.

A National Book Award finalist, The Tradition questions why and how we’ve become accustomed to terror: in the bedroom, the classroom, the workplace, and the movie theater. From mass shootings to rape to the murder of unarmed people by police, Brown interrupts complacency by locating each emergency in the garden of the body, where living things grow and wither—or survive.

A National Book Award finalist, The Tradition questions why and how we’ve become accustomed to terror: in the bedroom, the classroom, the workplace, and the movie theater. From mass shootings to rape to the murder of unarmed people by police, Brown interrupts complacency by locating each emergency in the garden of the body, where living things grow and wither—or survive.

In the urgency born of real danger, Brown’s work is at its most innovative. His invention of the duplex—a combination of the sonnet, the ghazal, and the blues—is an all-out exhibition of formal skill, and his lyrics move through elegy and memory with a breathless cadence. Jericho Brown is a poet of eros: here he wields this power as never before, touching the very heart of our cultural crisis.

Jericho Brown is a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard, and the National Endowment for the Arts, and he is the winner of a Whiting Award. Brown’s first book, Please (New Issues, 2008), won the American Book Award. His second book, The New Testament (Copper Canyon, 2014), won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. His third collection is The Tradition (Copper Canyon, 2019)—winner of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry and a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award. His poems have appeared in Bennington Review, BuzzFeed, Fence, jubilat, The New Republic, The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, TIME, and several volumes of The Best American Poetry. He is an associate professor and the director of the Creative Writing Program at Emory University.

The Tradition

poems by Jericho Brown

(Winner of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry)

Format: Paperback

Paperback

110 pages

ISBN-10 : 1556594860

ISBN-13 : 978-1556594861

Publisher : Copper Canyon Press

2 April 2019

Product Dimensions : 22.35 x 14.99 x 1.27 cm

Language: English

$17.00 list price

Jericho Brown

Awards and Honors

Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, 2020

Whiting Writers Award

American Book Award

National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship

Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University Fellowship

Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference Fellowship

Krakow Poetry Seminar Fellowship

John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship

Lambda Literary Trustee Award, 2020

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Awards & Prizes

Les Yeux de Berthe

Vous pouvez mépriser les yeux les plus célèbres,

Beaux yeux de mon enfant, par où filtre et s’enfuit

Je ne sais quoi de bon, de doux comme la Nuit!

Beaux yeux, versez sur moi vos charmantes ténèbres!

Grands yeux de mon enfant, arcanes adorés,

Vous ressemblez beaucoup à ces grottes magiques

Où, derrière l’amas des ombres léthargiques,

Scintillent vaguement des trésors ignorés!

Mon enfant a des yeux obscurs, profonds et vastes,

Comme toi, Nuit immense, éclairés comme toi!

Leurs feux sont ces pensers d’Amour, mêlés de Foi,

Qui pétillent au fond, voluptueux ou chastes.

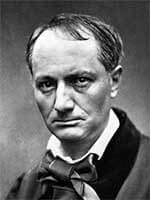

Charles Baudelaire

(1821-1867)

Les Yeux de Berthe

(poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Baudelaire, Baudelaire, Charles

Vergeelde brieven met een lintje erom

In verkleurde inkt de verdwenen stemmen

van broeders die nooit paters zouden worden.

Over geplooide superplies in zwijgende kasten,

en opwolkende wierook. De zinnen ademen

schuchter voor de sluier van hun namen, als

fluisteringen uit het hart. Ze dansten ooit

de horlepijp, maar de melodie daarvan zonk

traag weg uit hun oren als een steen in veen.

Bert Bevers

Eerder verschenen op Versindaba, Stellenbosch, februari 2014

Bert Bevers is a poet and writer who lives and works in Antwerp (Be)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

The Grey Monk

“I die, I die!” the Mother said,

“My children die for lack of bread.

What more has the merciless Tyrant said?”

The Monk sat down on the stony bed.

The blood red ran from the Grey Monk’s side,

His hands and feet were wounded wide,

His body bent, his arms and knees

Like to the roots of ancient trees.

His eye was dry; no tear could flow:

A hollow groan first spoke his woe.

He trembled and shudder’d upon the bed;

At length with a feeble cry he said:

“When God commanded this hand to write

In the studious hours of deep midnight,

He told me the writing I wrote should prove

The bane of all that on Earth I lov’d.

My Brother starv’d between two walls,

His Children’s cry my soul appalls;

I mock’d at the rack and griding chain,

My bent body mocks their torturing pain.

Thy father drew his sword in the North,

With his thousands strong he marched forth;

Thy Brother has arm’d himself in steel

To avenge the wrongs thy Children feel.

But vain the Sword and vain the Bow,

They never can work War’s overthrow.

The Hermit’s prayer and the Widow’s tear

Alone can free the World from fear.

For a Tear is an intellectual thing,

And a Sigh is the sword of an Angel King,

And the bitter groan of the Martyr’s woe

Is an arrow from the Almighty’s bow.

The hand of Vengeance found the bed

To which the Purple Tyrant fled;

The iron hand crush’d the Tyrant’s head

And became a Tyrant in his stead.”

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

The Grey Monk

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Belijdenis

Je moet niets verbranden. Zelfs geen mieren

als je denkt dat die een oprukkend leger zijn.

Dat heb ik wel gebiecht ja, dat heb ik toen wel

gebiecht. Ego te absolvo a peccatis tuis in nomine

Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti. Amen. Amen.

Ach, die 10 Ave Maria’s en 5 Paternosters

waarmee ik mijn zieltje destijds schoon waste.

Het blonk daarna weer als een ansjovisbuikje.

Nooit echt heb ik me onderworpen aan de sluier

van de dwang. Onrustige biechtelingen waren

er genoeg hoor, bang mokkend in hun eigen

schaduw. Vierduizend mijl dik waren voor hen

de muren van de hel. Zij leerden de beschroomde

tere tinten van berouw nooit kennen. Bleven

verhard in wrede gedachten, grauw als gummi.

Bert Bevers

Eerder verschenen bij Digther, Diksmuide, november 2013

Bert Bevers is a poet and writer who lives and works in Antwerp (Be)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Automne Malade

Automne malade et adoré

Tu mourras quand l’ouragan soufflera dans les roseraies

Quand il aura neigé

Dans les vergers

Pauvre automne

Meurs en blancheur et en richesse

De neige et de fruits mûrs

Au fond du ciel

Des éperviers planent

Sur les nixes nicettes aux cheveux verts et naines

Qui n’ont jamais aimé

Aux lisières lointaines

Les cerfs ont bramé

Et que j’aime ô saison que j’aime tes rumeurs

Les fruits tombant sans qu’on les cueille

Le vent et la forêt qui pleurent

Toutes leurs larmes en automne feuille à feuille

Les feuilles

Qu’on foule

Un train

Qui roule

La vie

S’écoule

Guillaume Apollinaire

(1880 – 1918)

Automne Malade

(Alcools – 1913)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Apollinaire, Guillaume, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Guillaume Apollinaire

To The Muses

Whether on Ida’s shady brow,

Or in the chambers of the East,

The chambers of the sun, that now

From ancient melody have ceas’d;

Whether in Heav’n ye wander fair,

Or the green corners of the earth,

Or the blue regions of the air,

Where the melodious winds have birth;

Whether on crystal rocks ye rove,

Beneath the bosom of the sea

Wand’ring in many a coral grove,

Fair Nine, forsaking Poetry!

How have you left the ancient love

That bards of old enjoy’d in you!

The languid strings do scarcely move!

The sound is forc’d, the notes are few!

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

To The Muses

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Chickamauga

One sunny autumn afternoon a child strayed away from its rude home in a small field and entered a forest unobserved. It was happy in a new sense of freedom from control, happy in the opportunity of exploration and adventure; for this child’s spirit, in bodies of its ancestors, had for thousands of years been trained to memorable feats of discovery and conquest—victories in battles whose critical moments were centuries, whose victors’ camps were cities of hewn stone. From the cradle of its race it had conquered its way through two continents and passing a great sea had penetrated a third, there to be born to war and dominion as a heritage.

The child was a boy aged about six years, the son of a poor planter. In his younger manhood the father had been a soldier, had fought against naked savages and followed the flag of his country into the capital of a civilized race to the far South. In the peaceful life of a planter the warrior-fire survived; once kindled, it is never extinguished. The man loved military books and pictures and the boy had understood enough to make himself a wooden sword, though even the eye of his father would hardly have known it for what it was. This weapon he now bore bravely, as became the son of an heroic race, and pausing now and again in the sunny space of the forest assumed, with some exaggeration, the postures of aggression and defense that he had been taught by the engraver’s art. Made reckless by the ease with which he overcame invisible foes attempting to stay his advance, he committed the common enough military error of pushing the pursuit to a dangerous extreme, until he found himself upon the margin of a wide but shallow brook, whose rapid waters barred his direct advance against the flying foe that had crossed with illogical ease. But the intrepid victor was not to be baffled; the spirit of the race which had passed the great sea burned unconquerable in that small breast and would not be denied. Finding a place where some bowlders in the bed of the stream lay but a step or a leap apart, he made his way across and fell again upon the rear-guard of his imaginary foe, putting all to the sword.

The child was a boy aged about six years, the son of a poor planter. In his younger manhood the father had been a soldier, had fought against naked savages and followed the flag of his country into the capital of a civilized race to the far South. In the peaceful life of a planter the warrior-fire survived; once kindled, it is never extinguished. The man loved military books and pictures and the boy had understood enough to make himself a wooden sword, though even the eye of his father would hardly have known it for what it was. This weapon he now bore bravely, as became the son of an heroic race, and pausing now and again in the sunny space of the forest assumed, with some exaggeration, the postures of aggression and defense that he had been taught by the engraver’s art. Made reckless by the ease with which he overcame invisible foes attempting to stay his advance, he committed the common enough military error of pushing the pursuit to a dangerous extreme, until he found himself upon the margin of a wide but shallow brook, whose rapid waters barred his direct advance against the flying foe that had crossed with illogical ease. But the intrepid victor was not to be baffled; the spirit of the race which had passed the great sea burned unconquerable in that small breast and would not be denied. Finding a place where some bowlders in the bed of the stream lay but a step or a leap apart, he made his way across and fell again upon the rear-guard of his imaginary foe, putting all to the sword.

Now that the battle had been won, prudence required that he withdraw to his base of operations. Alas; like many a mightier conqueror, and like one, the mightiest, he could not

curb the lust for war,

Nor learn that tempted Fate will leave the loftiest star.

Advancing from the bank of the creek he suddenly found himself confronted with a new and more formidable enemy: in the path that he was following, sat, bolt upright, with ears erect and paws suspended before it, a rabbit! With a startled cry the child turned and fled, he knew not in what direction, calling with inarticulate cries for his mother, weeping, stumbling, his tender skin cruelly torn by brambles, his little heart beating hard with terror—breathless, blind with tears—lost in the forest! Then, for more than an hour, he wandered with erring feet through the tangled undergrowth, till at last, overcome by fatigue, he lay down in a narrow space between two rocks, within a few yards of the stream and still grasping his toy sword, no longer a weapon but a companion, sobbed himself to sleep. The wood birds sang merrily above his head; the squirrels, whisking their bravery of tail, ran barking from tree to tree, unconscious of the pity of it, and somewhere far away was a strange, muffed thunder, as if the partridges were drumming in celebration of nature’s victory over the son of her immemorial enslavers. And back at the little plantation, where white men and black were hastily searching the fields and hedges in alarm, a mother’s heart was breaking for her missing child.

Hours passed, and then the little sleeper rose to his feet. The chill of the evening was in his limbs, the fear of the gloom in his heart. But he had rested, and he no longer wept. With some blind instinct which impelled to action he struggled through the undergrowth about him and came to a more open ground—on his right the brook, to the left a gentle acclivity studded with infrequent trees; over all, the gathering gloom of twilight. A thin, ghostly mist rose along the water. It frightened and repelled him; instead of recrossing, in the direction whence he had come, he turned his back upon it, and went forward toward the dark inclosing wood. Suddenly he saw before him a strange moving object which he took to be some large animal—a dog, a pig—he could not name it; perhaps it was a bear. He had seen pictures of bears, but knew of nothing to their discredit and had vaguely wished to meet one. But something in form or movement of this object—something in the awkwardness of its approach—told him that it was not a bear, and curiosity was stayed by fear. He stood still and as it came slowly on gained courage every moment, for he saw that at least it had not the long menacing ears of the rabbit. Possibly his impressionable mind was half conscious of something familiar in its shambling, awkward gait. Before it had approached near enough to resolve his doubts he saw that it was followed by another and another. To right and to left were many more; the whole open space about him were alive with them—all moving toward the brook.

They were men. They crept upon their hands and knees. They used their hands only, dragging their legs. They used their knees only, their arms hanging idle at their sides. They strove to rise to their feet, but fell prone in the attempt. They did nothing naturally, and nothing alike, save only to advance foot by foot in the same direction. Singly, in pairs and in little groups, they came on through the gloom, some halting now and again while others crept slowly past them, then resuming their movement. They came by dozens and by hundreds; as far on either hand as one could see in the deepening gloom they extended and the black wood behind them appeared to be inexhaustible. The very ground seemed in motion toward the creek. Occasionally one who had paused did not again go on, but lay motionless. He was dead. Some, pausing, made strange gestures with their hands, erected their arms and lowered them again, clasped their heads; spread their palms upward, as men are sometimes seen to do in public prayer.

Not all of this did the child note; it is what would have been noted by an elder observer; he saw little but that these were men, yet crept like babes. Being men, they were not terrible, though unfamiliarly clad. He moved among them freely, going from one to another and peering into their faces with childish curiosity. All their faces were singularly white and many were streaked and gouted with red. Something in this—something too, perhaps, in their grotesque attitudes and movements—reminded him of the painted clown whom he had seen last summer in the circus, and he laughed as he watched them. But on and ever on they crept, these maimed and bleeding men, as heedless as he of the dramatic contrast between his laughter and their own ghastly gravity. To him it was a merry spectacle. He had seen his father’s negroes creep upon their hands and knees for his amusement—had ridden them so, “making believe” they were his horses. He now approached one of these crawling figures from behind and with an agile movement mounted it astride. The man sank upon his breast, recovered, flung the small boy fiercely to the ground as an unbroken colt might have done, then turned upon him a face that lacked a lower jaw—from the upper teeth to the throat was a great red gap fringed with hanging shreds of flesh and splinters of bone. The unnatural prominence of nose, the absence of chin, the fierce eyes, gave this man the appearance of a great bird of prey crimsoned in throat and breast by the blood of its quarry. The man rose to his knees, the child to his feet. The man shook his fist at the child; the child, terrified at last, ran to a tree near by, got upon the farther side of it and took a more serious view of the situation. And so the clumsy multitude dragged itself slowly and painfully along in hideous pantomime—moved forward down the slope like a swarm of great black beetles, with never a sound of going—in silence profound, absolute.

Instead of darkening, the haunted landscape began to brighten. Through the belt of trees beyond the brook shone a strange red light, the trunks and branches of the trees making a black lacework against it. It struck the creeping figures and gave them monstrous shadows, which caricatured their movements on the lit grass. It fell upon their faces, touching their whiteness with a ruddy tinge, accentuating the stains with which so many of them were freaked and maculated. It sparkled on buttons and bits of metal in their clothing. Instinctively the child turned toward the growing splendor and moved down the slope with his horrible companions; in a few moments had passed the foremost of the throng—not much of a feat, considering his advantages. He placed himself in the lead, his wooden sword still in hand, and solemnly directed the march, conforming his pace to theirs and occasionally turning as if to see that his forces did not straggle. Surely such a leader never before had such a following.

Scattered about upon the ground now slowly narrowing by the encroachment of this awful march to water, were certain articles to which, in the leader’s mind, were coupled no significant associations: an occasional blanket tightly rolled lengthwise, doubled and the ends bound together with a string; a heavy knapsack here, and there a broken rifle—such things, in short, as are found in the rear of retreating troops, the “spoor” of men flying from their hunters. Everywhere near the creek, which here had a margin of lowland, the earth was trodden into mud by the feet of men and horses. An observer of better experience in the use of his eyes would have noticed that these footprints pointed in both directions; the ground had been twice passed over—in advance and in retreat. A few hours before, these desperate, stricken men, with their more fortunate and now distant comrades, had penetrated the forest in thousands. Their successive battalions, breaking into swarms and reforming in lines, had passed the child on every side—had almost trodden on him as he slept. The rustle and murmur of their march had not awakened him. Almost within a stone’s throw of where he lay they had fought a battle; but all unheard by him were the roar of the musketry, the shock of the cannon, “the thunder of the captains and the shouting.” He had slept through it all, grasping his little wooden sword with perhaps a tighter clutch in unconscious sympathy with his martial environment, but as heedless of the grandeur of the struggle as the dead who had died to make the glory.

The fire beyond the belt of woods on the farther side of the creek, reflected to earth from the canopy of its own smoke, was now suffusing the whole landscape. It transformed the sinuous line of mist to the vapor of gold. The water gleamed with dashes of red, and red, too, were many of the stones protruding above the surface. But that was blood; the less desperately wounded had stained them in crossing. On them, too, the child now crossed with eager steps; he was going to the fire. As he stood upon the farther bank he turned about to look at the companions of his march. The advance was arriving at the creek. The stronger had already drawn themselves to the brink and plunged their faces into the flood. Three or four who lay without motion appeared to have no heads. At this the child’s eyes expanded with wonder; even his hospitable understanding could not accept a phenomenon implying such vitality as that. After slaking their thirst these men had not had the strength to back away from the water, nor to keep their heads above it. They were drowned. In rear of these, the open spaces of the forest showed the leader as many formless figures of his grim command as at first; but not nearly so many were in motion. He waved his cap for their encouragement and smilingly pointed with his weapon in the direction of the guiding light—a pillar of fire to this strange exodus.

Confident of the fidelity of his forces, he now entered the belt of woods, passed through it easily in the red illumination, climbed a fence, ran across a field, turning now and again to coquet with his responsive shadow, and so approached the blazing ruin of a dwelling. Desolation everywhere! In all the wide glare not a living thing was visible. He cared nothing for that; the spectacle pleased, and he danced with glee in imitation of the wavering flames. He ran about, collecting fuel, but every object that he found was too heavy for him to cast in from the distance to which the heat limited his approach. In despair he flung in his sword—a surrender to the superior forces of nature. His military career was at an end.

Shifting his position, his eyes fell upon some outbuildings which had an oddly familiar appearance, as if he had dreamed of them. He stood considering them with wonder, when suddenly the entire plantation, with its inclosing forest, seemed to turn as if upon a pivot. His little world swung half around; the points of the compass were reversed. He recognized the blazing building as his own home!

For a moment he stood stupefied by the power of the revelation, then ran with stumbling feet, making a half-circuit of the ruin. There, conspicuous in the light of the conflagration, lay the dead body of a woman—the white face turned upward, the hands thrown out and clutched full of grass, the clothing deranged, the long dark hair in tangles and full of clotted blood. The greater part of the forehead was torn away, and from the jagged hole the brain protruded, overflowing the temple, a frothy mass of gray, crowned with clusters of crimson bubbles—the work of a shell.

The child moved his little hands, making wild, uncertain gestures. He uttered a series of inarticulate and indescribable cries—something between the chattering of an ape and the gobbling of a turkey—a startling, soulless, unholy sound, the language of a devil. The child was a deaf mute.

Then he stood motionless, with quivering lips, looking down upon the wreck.

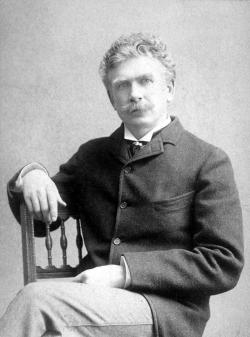

Ambrose Bierce

(1842-1914)

Chickamauga

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bierce, Ambrose, Bierce, Ambrose

Das Märchen vom Ritter Blaubart

Es war einmal ein gewaltiger Rittersmann, der hatte viel Geld und Gut, und lebte auf seinem Schlosse herrlich und in Freuden. Er hatte einen blauen Bart, davon man ihn nur Ritter Blaubart nannte, obschon er eigentlich anders hieß, aber sein wahrer Name ist verloren gegangen.

Dieser Ritter hatte sich schon mehr als einmal verheiratet, allein man hätte gehört, daß alle seine Frauen schnell nacheinander gestorben seien, ohne daß man eigentlich ihre Krankheit erfahren hatte. Nun ging Ritter Blaubart abermals auf Freiersfüßen, und da war eine Edeldame in seiner Nachbarschaft, die hatte zwei schöne Töchter und einige ritterliche Söhne, und diese Geschwister liebten einander sehr zärtlich. Als nun Ritter Blaubart die eine dieser Töchter heiraten wollte, hatte keine von beiden rechte Lust, denn sie fürchteten sich vor des Ritters blauem Bart, und mochten sich auch nicht gern voneinander trennen. Aber der Ritter lud die Mutter, die Töchter und die Brüder samt und sonders auf sein großes schönes Schloß zu Gaste, und verschaffte ihnen dort so viel angenehmen Zeitvertreib und so viel Vergnügen durch Jagden, Tafeln, Tänze, Spiele und sonstige Freudenfeste, daß sich endlich die jüngste der Schwestern ein Herz faßte, und sich entschloß, Ritter Blaubarts Frau zu werden. Bald darauf wurde auch die Hochzeit mit vieler Pracht gefeiert.

Dieser Ritter hatte sich schon mehr als einmal verheiratet, allein man hätte gehört, daß alle seine Frauen schnell nacheinander gestorben seien, ohne daß man eigentlich ihre Krankheit erfahren hatte. Nun ging Ritter Blaubart abermals auf Freiersfüßen, und da war eine Edeldame in seiner Nachbarschaft, die hatte zwei schöne Töchter und einige ritterliche Söhne, und diese Geschwister liebten einander sehr zärtlich. Als nun Ritter Blaubart die eine dieser Töchter heiraten wollte, hatte keine von beiden rechte Lust, denn sie fürchteten sich vor des Ritters blauem Bart, und mochten sich auch nicht gern voneinander trennen. Aber der Ritter lud die Mutter, die Töchter und die Brüder samt und sonders auf sein großes schönes Schloß zu Gaste, und verschaffte ihnen dort so viel angenehmen Zeitvertreib und so viel Vergnügen durch Jagden, Tafeln, Tänze, Spiele und sonstige Freudenfeste, daß sich endlich die jüngste der Schwestern ein Herz faßte, und sich entschloß, Ritter Blaubarts Frau zu werden. Bald darauf wurde auch die Hochzeit mit vieler Pracht gefeiert.

Nach einer Zeit sagte der Ritter Blaubart zu seiner jungen Frau: »Ich muß verreisen, und übergebe dir die Obhut über das ganze Schloß, Haus und Hof, mit allem, was dazu gehört. Hier sind auch die Schlüssel zu allen Zimmern und Gemächern, in alle diese kannst du zu jeder Zeit eintreten. Aber dieser kleine goldne Schlüssel schließt das hinterste Kabinett am Ende der großen Zimmerreihe. In dieses, meine Teure, muß ich dir verbieten zu gehen, so lieb dir meine Liebe und dein Leben ist. Würdest du dieses Kabinett öffnen, so erwartet dich die schrecklichste Strafe der Neugier. Ich müßte dir dann mit eigner Hand das Haupt vom Rumpfe trennen!« – Die Frau wollte auf diese Rede den kleinen goldnen Schlüssel nicht annehmen, indes mußte sie dies tun, um ihn sicher aufzubewahren, und so schied sie von ihrem Mann mit dem Versprechen, daß es ihr nie einfallen werde, jenes Kabinett aufzuschließen und es zu betreten.

Als der Ritter fort war, erhielt die junge Frau Besuch von ihrer Schwester und ihren Brüdern, die gerne auf die Jagd gingen; und nun wurden mit Lust alle Tage die Herrlichkeiten in den vielen vielen Zimmern des Schlosses durchmustert, und so kamen die Schwestern auch endlich an das Kabinett. Die Frau wollte, obschon sie selbst große Neugierde trug, durchaus nicht öffnen, aber die Schwester lachte ob ihrer Bedenklichkeit, und meinte, daß Ritter Blaubart darin doch nur aus Eigensinn das Kostbarste und Wertvollste von seinen Schätzen verborgen halte. Und so wurde der Schlüssel mit einigem Zagen in das Schloß gesteckt, und da flog auch gleich mit dumpfem Geräusch die Türe auf, und in dem sparsam erhellten Zimmer zeigten sich – ein entsetzlicher Anblick! – die blutigen Häupter aller früheren Frauen Ritter Blaubarts, die ebensowenig, wie die jetzige, dem Drang der Neugier hatten widerstehen können, und die der böse Mann alle mit eigner Hand enthauptet hatte. Vom Tod geschüttelt, wichen jetzt die Frauen und ihre Schwester zurück; vor Schreck war der Frau der Schlüssel entfallen, und als sie ihn aufhob, waren Blutflecke daran, die sich nicht abreiben ließen, und ebensowenig gelang es, die Türe wieder zuzumachen, denn das Schloß war bezaubert, und indem verkündeten Hörner die Ankunft Berittner vor dem Tore der Burg. Die Frau atmete auf und glaubte, es seien ihre Brüder, die sie von der Jagd zurück erwartete, aber es war Ritter Blaubart selbst, der nichts Eiligeres zu tun hatte, als nach seiner Frau zu fragen, und als diese ihm bleich, zitternd und bestürzt entgegentrat, so fragte er nach dem Schlüssel; sie wollte den Schlüssel holen und er folgte ihr auf dem Fuße, und als er die Flecken am Schlüssel sah, so verwandelten sich alle seine Geberden, und er schrie: »Weib, du mußt nun von meinen Händen sterben! Alle Gewalt habe ich dir gelassen! Alles war dein! Reich und schön war dein Leben! Und so gering war deine Liebe zu mir, du schlechte Magd, daß du meine einzige geringe Bitte, meinen ernsten Befehl nicht beachtet hast? Bereite dich zum Tode! Es ist aus mit dir!«

Voll Entsetzen und Todesangst eilte die Frau zu ihrer Schwester, und bat sie, geschwind auf die Turmzinne zu steigen und nach ihren Brüdern zu spähen, und diesen, sobald sie sie erblicke, ein Notzeichen zu geben, während sie sich auf den Boden warf, und zu Gott um ihr Leben flehte. Und dazwischen rief sie: »Schwester! Siehst du noch niemand!« – »Niemand!« klang die trostlose Antwort. – »Weib! komm herunter!« schrie Ritter Blaubart, »deine Frist ist aus!«

Voll Entsetzen und Todesangst eilte die Frau zu ihrer Schwester, und bat sie, geschwind auf die Turmzinne zu steigen und nach ihren Brüdern zu spähen, und diesen, sobald sie sie erblicke, ein Notzeichen zu geben, während sie sich auf den Boden warf, und zu Gott um ihr Leben flehte. Und dazwischen rief sie: »Schwester! Siehst du noch niemand!« – »Niemand!« klang die trostlose Antwort. – »Weib! komm herunter!« schrie Ritter Blaubart, »deine Frist ist aus!«

»Schwester! siehst du niemand?« schrie die Zitternde. »Eine Staubwolke – aber ach, es sind Schafe!« antwortete die Schwester. – »Weib! komm herunter, oder ich hole dich!« schrie Ritter Blaubart.

»Erbarmen! Ich komme ja sogleich! Schwester! siehst du niemand?« – »Zwei Ritter kommen zu Roß daher, sie sahen mein Zeichen, sie reiten wie der Wind.« –

»Weib! Jetzt hole ich dich!« donnerte Blaubarts Stimme, und da kam er die Treppe herauf. Aber die Frau gewann Mut, warf ihre Zimmertüre ins Schloß, und hielt sie fest, und dabei schrie sie samt ihrer Schwester so laut um Hülfe, wie sie beide nur konnten. Indessen eilten die Brüder wie der Blitz herbei, stürmten die Treppe hinauf und kamen eben dazu, wie Ritter Blaubart die Türe sprengte und mit gezücktem Schwert in das Zimmer drang. Ein kurzes Gefecht und Ritter Blaubart lag tot am Boden. Die Frau war erlöst, konnte aber die Folgen ihrer Neugier lange nicht verwinden.

Ludwig Bechstein

(1801 – 1860)

Das Märchen vom Ritter Blaubart

Sämtliche Märchen

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bechstein, Bechstein, Ludwig, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Con Large Comme Un Estuaire

Con large comme un estuaire

Où meurt mon amoureux reflux

Tu as la saveur poissonnière

l’odeur de la bite et du cul

La fraîche odeur trouduculière

Femme ô vagin inépuisable

Dont le souvenir fait bander

Tes nichons distribuent la manne

Tes cuisses quelle volupté

même tes menstrues sanglantes

Sont une liqueur violente

La rose-thé de ton prépuce

Auprès de moi s’épanouit

On dirait d’un vieux boyard russe

Le chibre sanguin et bouffi

Lorsqu’au plus fort de la partouse

Ma bouche à ton noeud fait ventouse.

Guillaume Apollinaire

(1880 – 1918)

Con Large Comme Un Estuaire

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Apollinaire, Guillaume, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Guillaume Apollinaire

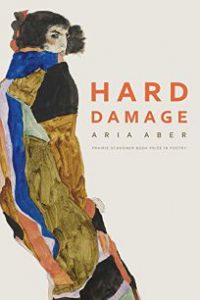

Hard Damage works to relentlessly interrogate the self and its shortcomings. In lyric and documentary poems and essayistic fragments, Aria Aber explores the historical and personal implications of Afghan American relations.

Drawing on material dating back to the 1950s, she considers the consequences of these relations—in particular the funding of the Afghan mujahedeen, which led to the Taliban and modern-day Islamic terrorism—for her family and the world at large.

Drawing on material dating back to the 1950s, she considers the consequences of these relations—in particular the funding of the Afghan mujahedeen, which led to the Taliban and modern-day Islamic terrorism—for her family and the world at large.

Invested in and suspicious of the pain of family and the shame of selfhood, the speakers of these richly evocative and musical poems mourn the magnitude of citizenship as a state of place and a state of mind. While Hard Damage is framed by free-verse poetry, the middle sections comprise a lyric essay in fragments and a long documentary poem. Aber explores Rilke in the original German, the urban melancholia of city life, inherited trauma, and displacement on both linguistic and environmental levels, while employing surrealist and eerily domestic imagery.

One hears everything here, where the landscape

is a clean knife, slicing the mute—just a cat

wiping its face, roofs with snow for weeks, ice

falling from fir trees like books pushed off a shelf.

“The book is an academic asset. It is fine literature, from beyond the borders of the English-speaking sensibilities. Students of literature, political science, sociology, foreign affairs, and many other disciplines can benefit from Hard Damage…” – NY Journal of Books

Aria Aber was raised in Germany, where she was born to Afghan refugees. Her debut book Hard Damage won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry and will be published in September 2019. Her poems are forthcoming or have appeared in The New Yorker, New Republic, Kenyon Review, The Yale Review, Poem-A-Day, Narrative, Muzzle Magazine, Wasafiri and others. A graduate from the NYU MFA in Creative Writing, where she was the Writers in Public Schools Fellow, she holds awards and fellowships from Kundiman and Dickinson House and was the 2018-2019 Ron Wallace Poetry Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute of Creative Writing. She’s currently based in Berlin and is at work on her second book.

Aria Aber (Author)

Hard Damage

Poetry

Series: Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Poetry

Paperback

126 pages

Publisher: University of Nebraska Press

2019

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1496215702

ISBN-13: 978-1496215703

Product Dimensions:

6 x 0.3 x 9 inches

$17.95

# new books

Aria Aber:

Hard Damage

Poetry

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News

Le Poète

ODE

(Couronnée aux jeux floraux)

Des longs ennuis du jour quand le soir me délivre,

Poète aux chants divins, j’ouvre en rêvant ton livre,

Je me recueille en toi, dans l’ombre et loin du bruit ;

De ton monde idéal, j’ose aborder la rive :

Tes chants que je répète, à mon âme attentive

Semblent plus purs la nuit !

Mais qu’il reste caché, ce trouble de mon âme,

De moi rien ne t’émeut, ni louange, ni blâme.

Quelques hivers à peine ont passé sur mon front…

Et qu’importe à ta muse, en tous lieux adorée,

Qu’au sein de ses foyers une femme ignorée

S’attendrisse à ton nom !

Qui te dira qu’aux sons de ta lyre sublime,

À ses accords divins, ma jeune âme s’anime,

Laissant couler ensemble et ses vers et ses pleurs ?

Quand près de moi ta muse un instant s’est posée,

Je chante…. ainsi le ciel, en versant sa rosée,

Entr’ouvre quelques fleurs.

Poètes ! votre sort est bien digne d’envie.

Le Dieu qui nous créa vous fit une autre vie,

L’horizon ne sert point de limite à vos yeux,

D’un univers plus grand vous sondez le mystère,

Et quand, pauvres mortels, nous vivons sur la terre,

Vous vivez dans les cieux !

Et si, vous éloignant des voûtes éternelles,

Vous descendez vers nous pour reposer vos ailes,

Notre monde à vos yeux se dévoile plus pur ;

L’hiver garde des fleurs, les bois un vert feuillage,

La rose son parfum, les oiseaux leur ramage,

Et le ciel son azur.

Si Dieu, vous révélant les maux de l’existence,

Au milieu de vos chants fait naître la souffrance,

Votre âme, en sa douleur poursuivant son essor,

Comme au temps des beaux jours vibre dans ses alarmes ;

Le monde s’aperçoit, quand vous montrez vos larmes,

Que vous chantez encor !

Le malheur se soumet aux formes du génie,

En passant par votre âme, il devient harmonie.

Votre plainte s’exhale en sons mélodieux.

L’ouragan qui, la nuit, rugit et se déchaîne,

S’il rencontre en son cours la harpe éolienne,

Devient harmonieux.

Moi, sur mes jeunes ans j’ai vu gronder l’orage,

Le printemps fut sans fleurs, et l’été, sans ombrage ;

Aucun ange du ciel n’a regardé mes pleurs.

Que ne puis-je, changeant l’absinthe en ambroisie,

Comme vous, aux accords d’un chant de poésie

Endormir mes douleurs !

À notre âme, ici-bas , il n’est rien qui réponde ;

Poètes inspirés, montrez-nous votre monde !

À ce vaste désert, venez nous arracher.

Pour le divin banquet votre table se dresse…

Oh ! laissez, de la coupe où vous puisez l’ivresse,

Mes lèvres s’approcher !

Oui, penchez jusqu’à moi voire main que j’implore ;

Votre coupe est trop loin, baissez, baissez encore !…

Répandez dans mes vers l’encens inspirateur.

Pour monter jusqu’à vous, mon pied tremble et chancelle…

Poètes ! descendez, et portez sur votre aile

Une timide sœur !

Sophie d’Arbouville

(1810-1850)

Le Poète. Ode

Poésies et nouvelles (1840)

•fleursdumal.nl

More in: Arbouville, Sophie d', Archive A-B, Archive A-B

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature