Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

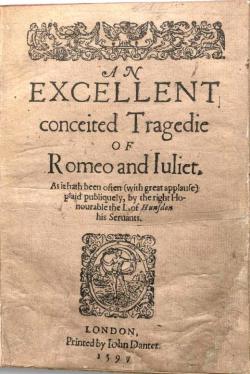

It is well known that the hatred borne by one family against another, and the strife of parties, which often led to bloodshed in the Italian cities during the Middle Ages, so vividly described by Shakespeare in “Romeo and Juliet,” was not confined to the Montecchi and Ciapelletti of Verona, but existed with equal animosity in almost every other town of that beautiful peninsula.

T he greatest men among them were the victims; and crowds of exiles—families who but the day before were in the full enjoyment of the luxuries of life and the endearing associations of home—were every now and then seen issuing from the gates of their native cities, deprived of every possession, and with melancholy and slow steps dragging their wearied limbs to the nearest asylum offered them, thence to commence a new career of dependence and poverty, to endure to the end of their lives, or until some lucky accident should enable them to change places with their enemies, making those the sufferers who were late the tyrants.

he greatest men among them were the victims; and crowds of exiles—families who but the day before were in the full enjoyment of the luxuries of life and the endearing associations of home—were every now and then seen issuing from the gates of their native cities, deprived of every possession, and with melancholy and slow steps dragging their wearied limbs to the nearest asylum offered them, thence to commence a new career of dependence and poverty, to endure to the end of their lives, or until some lucky accident should enable them to change places with their enemies, making those the sufferers who were late the tyrants.

In that country, where each town formed an independent State, to change one for the other was to depart from the spot cherished as a country and a home for distant banishment—or worse; for as each city entertained either hatred or contempt for its neighbour, it often happened that the mourning exile was obliged to take up his abode among a people whom he had injured or scoffed. Foreign service offered a resource to the young and bold among the men. But lovely Italy was to be left, the ties of young hearts severed, and all the endearing associations of kin and country broken and scattered for ever. The Italians were always peculiarly susceptible to these misfortunes. They loved their native walls, the abodes of their ancestors, the familiar scenes of youth, with all the passionate fervour characteristic of that clime.

It was therefore no uncommon thing for any one among them, like Foscari of Venice, to prefer destitution and danger in their own city, to a precarious subsistence among strangers in distant lands; or, if compelled to quit the beloved precincts of their native walls, still to hover near, ready to avail themselves of the first occasion that should present itself for reversing the decree that condemned them to misery.

For three days and nights there had been warfare in the streets of Siena,—blood flowed in torrents,—yet the cries and groans of the fallen but excited their friends to avenge them—not their foes to spare. On the fourth morning, Ugo Mancini, with a scanty band of followers, was driven from the town; succours from Florence had arrived for his enemies, and he was forced to yield. Burning with rage, writhing with an impotent thirst for vengeance, Ugo went round to the neighbouring villages to rouse them, not against his native town, but the victorious Tolomei. Unsuccessful in these endeavours, he next took the more equivocal step of seeking warlike aid from the Pisans. But Florence kept Pisa in check, and Ugo found only an inglorious refuge where he had hoped to acquire active allies. He had been wounded in these struggles; but, animated by a superhuman spirit, he had forgotten his pain and surmounted his weakness; nor was it until a cold refusal was returned to his energetic representations, that he sank beneath his physical sufferings. He was stretched on a bed of torture when he received intelligence that an edict of perpetual banishment and confiscation of property was passed against him. His two children, beggars now, were sent to him. His wife was dead, and these were all of near relations that he possessed. His bitter feelings were still too paramount for him to receive comfort from their presence; yet these agitated and burning emotions appeared in after-times a remnant of happiness compared to the total loss of every hope—the wasting inaction of sickness and of poverty.

For five years Ugo Mancini lay stretched on his couch, alternating between states of intense pain and overpowering weakness; and then he died. During this interval, the wreck of his fortunes, consisting of the rent of a small farm, and the use of some money lent, scantily supported him. His few relatives and followers were obliged to seek their subsistence elsewhere, and he remained alone to his pain, and to his two children, who yet clung to the paternal side.

Hatred to his foes, and love for his native town, were the sentiments that possessed his soul, and which he imparted in their full force to the plastic mind of his son, which received like molten metal the stamp he desired to impress. Lorenzo was scarcely twelve years old at the period of his father’s exile, and he naturally turned with fondness towards the spot where he had enjoyed every happiness, where each hour had been spent in light-hearted hilarity, and the kindness and observance of many attended on his steps. Now, how sad the contrast!—dim penury—a solitude cheered by no encouraging smiles or sunny flatteries—perpetual attendance on his father, and untimely cares, cast their dark shadows over his altered lot.

Lorenzo was a few years older than his sister. Friendless and destitute as was the exile’s family, it was he who overlooked its moderate disbursements, who was at once his father’s nurse and his sister’s guardian, and acted as the head of the family during the incapacity of his parent. But instead of being narrowed or broken in spirit by these burdens, his ardent soul rose to meet them, and grew enlarged and lofty from the very calls made upon it. His look was serious, not careworn; his manner calm, not humble; his voice had all the tenderness of a woman—his eye all the pride and fire of a hero.

Still his unhappy father wasted away, and Lorenzo’s hours were entirely spent beside his bed. He was indefatigable in his attentions—weariness never seemed to overcome him. His limbs were always alert—his speech inspiriting and kind. His only pastime was during any interval in his parent’s sufferings, to listen to his eulogiums on his native town, and to the history of the wrongs which, from time immemorial, the Mancini had endured from the Tolomei. Lorenzo, though replete with noble qualities, was still an Italian; and fervent love for his birthplace, and violent hatred towards the foes of his house, were the darling passions of his heart. Nursed in loneliness, they acquired vigour; and the nights he spent in watching his father were varied by musing on the career he should hereafter follow—his return to his beloved Siena, and the vengeance he would take on his enemies.

Ugo often said, I die because I am an exile:—at length these words were fulfilled, and the unhappy man sank beneath the ills of fortune. Lorenzo saw his beloved father expire—his father, whom he loved. He seemed to deposit in his obscure grave all that best deserved reverence and honour in the world; and turning away his steps, he lamented the loss of the sad occupation of so many years, and regretted the exchange he made from his father’s sick bed to a lonely and unprized freedom.

The first use he made of the liberty he had thus acquired was to return to Siena with his sister. He entered his native town as if it were a paradise, and he found it a desert in all save the hues of beauty and delight with which his imagination loved to invest it. There was no one to whom he could draw near in friendship within the whole circuit of its walls. According to the barbarous usage of the times, his father’s palace had been razed, and the mournful ruins stood as a tomb to commemorate the fall of his fortunes. Not as such did Lorenzo view them; he often stole out at nightfall, when the stars alone beheld his enthusiasm, and, clambering to the highest part of the massy fragments, spent long hours in mentally rebuilding the desolate walls, and in consecrating once again the weed-grown hearth to family love and hospitable festivity. It seemed to him that the air was more balmy and light, breathed amidst these memorials of the past; and his heart warmed with rapture over the tale they told of what his progenitors had been—what he again would be.

Yet, had he viewed his position sanely, he would have found it full of mortification and pain; and he would have become aware that his native town was perhaps the only place in the world where his ambition would fail in the attainment of its aim. The Tolomei reigned over it. They had led its citizens to conquest, and enriched them with spoils. They were adored; and to flatter them, the populace were prone to revile and scoff at the name of Mancini. Lorenzo did not possess one friend within its walls: he heard the murmur of hatred as he passed along, and beheld his enemies raised to the pinnacle of power and honour; and yet, so strangely framed is the human heart, that he continued to love Siena, and would not have exchanged his obscure and penurious abode within its walls to become the favoured follower of the German Emperor. Such a place, through education and the natural prejudices of man, did Siena hold in his imagination, that a lowly condition there seemed a nobler destiny than to be great in any other spot.

To win back the friendship of its citizens and humble his enemies was the dream that shed so sweet an influence over his darkened hours. He dedicated his whole being to this work, and he did not doubt but that he should succeed. The house of Tolomei had for its chief a youth but a year or two older than himself—with him, when an opportunity should present itself, he would enter the lists. It seemed the bounty of Providence that gave him one so nearly equal with whom to contend; and during the interval that must elapse before they could clash, he was busy in educating himself for the struggle. Count Fabian dei Tolomei bore the reputation of being a youth full of promise and talent; and Lorenzo was glad to anticipate a worthy antagonist. He occupied himself in the practice of arms, and applied with perseverance to the study of the few books that fell in his way. He appeared in the market-place on public occasions modestly attired; yet his height, his dignified carriage, and the thoughtful cast of his noble countenance, drew the observation of the bystanders;—though, such was the prejudice against his name, and the flattery of the triumphant party, that taunts and maledictions followed him. His nobility of appearance was called pride; his affability, meanness; his aspiring views, faction;—and it was declared that it would be a happy day when he should no longer blot their sunshine with his shadow. Lorenzo smiled,—he disdained to resent, or even to feel, the mistaken insults of the crowd, who, if fortune changed, would the next day throw up their caps for him. It was only when loftier foes approached that his brow grew dark, that he drew himself up to his full height, repaying their scorn with glances of defiance and hate.

But although he was ready in his own person to encounter the contumely of his townsmen, and walked on with placid mien, regardless of their sneers, he carefully guarded his sister from such scenes. She was led by him each morning, closely veiled, to hear mass in an obscure church. And when, on feast-days, the public walks were crowded with cavaliers and dames in splendid attire, and with citizens and peasants in their holiday garb, this gentle pair might be seen in some solitary and shady spot, Flora knew none to love except her brother—she had grown under his eyes from infancy; and while he attended on the sick-bed of their father, he was father, brother, tutor, guardian to her—the fondest mother could not have been more indulgent; and yet there was mingled a something beyond, pertaining to their difference of sex. Uniformly observant and kind, he treated her as if she had been a high-born damsel, nurtured in her gayest bower.

But although he was ready in his own person to encounter the contumely of his townsmen, and walked on with placid mien, regardless of their sneers, he carefully guarded his sister from such scenes. She was led by him each morning, closely veiled, to hear mass in an obscure church. And when, on feast-days, the public walks were crowded with cavaliers and dames in splendid attire, and with citizens and peasants in their holiday garb, this gentle pair might be seen in some solitary and shady spot, Flora knew none to love except her brother—she had grown under his eyes from infancy; and while he attended on the sick-bed of their father, he was father, brother, tutor, guardian to her—the fondest mother could not have been more indulgent; and yet there was mingled a something beyond, pertaining to their difference of sex. Uniformly observant and kind, he treated her as if she had been a high-born damsel, nurtured in her gayest bower.

Her attire was simple—but thus, she was instructed, it befitted every damsel to dress; her needle-works were such as a princess might have emulated; and while she learnt under her brother’s tutelage to be reserved, studious of obscurity, and always occupied, she was taught that such were the virtues becoming her sex, and no idea of dependence or penury was raised in her mind. Had he been the sole human being that approached her, she might have believed herself to be on a level with the highest in the land; but coming in contact with dependants in the humble class of life, Flora became acquainted with her true position; and learnt, at the same time, to understand and appreciate the unequalled kindness and virtues of her brother.

Two years passed while brother and sister continued, in obscurity and poverty, cherishing hope, honour, and mutual love. If an anxious thought ever crossed Lorenzo, it was for the future destiny of Flora, whose beauty as a child gave promise of perfect loveliness hereafter. For her sake he was anxious to begin the career he had marked out for himself, and resolved no longer to delay his endeavours to revive his party in Siena, and to seek rather than avoid a contest with the young Count Fabian, on whose overthrow he would rise—Count Fabian, the darling of the citizens, vaunted as a model for a youthful cavalier, abounding in good qualities, and so adorned by gallantry, subtle wit, and gay, winning manners, that he stepped by right of nature, as well as birth, on the pedestal which exalted him the idol of all around.

It was on a day of public feasting that Lorenzo first presented himself in rivalship with Fabian. His person was unknown to the count, who, in all the pride of rich dress and splendid accoutrements, looked with a smile of patronage on the poorly-mounted and plainly-attired youth, who presented himself to run a tilt with him. But before the challenge was accepted, the name of his antagonist was whispered to Fabian; then, all the bitterness engendered by family feuds; all the spirit of vengeance, which had been taught as a religion, arose at once in the young noble’s heart; he wheeled round his steed, and, riding rudely up to his competitor, ordered him instantly to retire from the course, nor dare to disturb the revels of the citizens by the hated presence of a Mancini. Lorenzo answered with equal scorn; and Fabian, governed by uncontrollable passion, called together his followers to drive the youth with ignominy from the lists. A fearful array was mustered against the hateful intruder; but had their number been trebled, the towering spirit of Lorenzo had met them all. One fell—another was disabled by his weapon before he was disarmed and made prisoner; but his bravery did not avail to extract admiration from his prejudiced foes: they rather poured execrations on him for its disastrous effects, as they hurried him to a dungeon, and called loudly for his punishment and death.

Far from this scene of turmoil and bloodshed, in her poor but quiet chamber, in a remote and obscure part of the town, sat Flora, occupied by her embroidery, musing, as she worked, on her brother’s project, and anticipating his success. Hours passed, and Lorenzo did not return; the day declined, and still he tarried. Flora’s busy fancy forged a thousand causes for the delay. Her brother’s prowess had awaked the chilly zeal of the partisans of their family;—he was doubtless feasting among them, and the first stone was laid for the rebuilding of their house. At last, a rush of steps upon the staircase, and a confused clamour of female voices calling loudly for admittance, made her rise and open the door;—in rushed several women—dismay was painted on their faces—their words flowed in torrents—their eager gestures helped them to a meaning, and, though not without difficulty, amidst the confusion, Flora heard of the disaster and imprisonment of her brother—of the blood shed by his hand, and the fatal issue that such a deed ensured. She grew pale as marble. Her young heart was filled with speechless terror; she could form no image of the thing she dreaded, but its indistinct idea was full of fear. Lorenzo was in prison—Count Fabian had placed him there—he was to die! Overwhelmed for a moment by such tidings, yet she rose above their benumbing power, and without proffering a word, or listening to the questions and remonstrances of the women, she rushed past them, down the high staircase, into the street; and then with swift pace to where the public prison was situated. She knew the spot she wished to reach, but she had so seldom quitted her home that she soon got entangled among the streets, and proceeded onwards at random. Breathless, at length, she paused before the lofty portal of a large palace—no one was near—the fast fading twilight of an Italian evening had deepened into absolute darkness. At this moment the glare of flambeaux was thrown upon the street, and a party of horsemen rode up; they were talking and laughing gaily. She heard one addressed as Count Fabian: she involuntarily drew back with instinctive hate; and then rushed forward and threw herself at his horse’s feet, exclaiming, “Save my brother!” The young cavalier reined up shortly his prancing steed, angrily reproving her for her heedlessness, and, without deigning another word, entered the courtyard. He had not, perhaps, heard her prayer;—he could not see the suppliant, he spoke but in the impatience of the moment;—but the poor child, deeply wounded by what had the appearance of a personal insult, turned proudly from the door, repressing the bitter tears that filled her eyes. Still she walked on; but night took from her every chance of finding her way to the prison, and she resolved to return home, to engage one of the women of the house, of which she occupied a part, to accompany her. But even to find her way back became matter of difficulty; and she wandered on, discovering no clue to guide her, and far too timid to address any one she might chance to meet. Fatigue and personal fear were added to her other griefs, and tears streamed plentifully down her cheeks as she continued her hopeless journey! At length, at the corner of a street, she recognised an image of the Madonna in a niche, with a lamp burning over it, familiar to her recollection as being near her home. With characteristic piety she knelt before it in thankfulness, and was offering a prayer for Lorenzo, when the sound of steps made her start up, and her brother’s voice hailed, and her brother’s arms encircled her; it seemed a miracle, but he was there, and all her fears were ended.

Lorenzo anxiously asked whither she had been straying; her explanation was soon given; and he in return related the misfortunes of the morning—the fate that impended over him, averted by the generous intercession of young Fabian himself; and yet—he hesitated to unfold the bitter truth—he was not freely pardoned—he stood there a banished man, condemned to die if the morrow’s sun found him within the walls of Siena.

They had arrived, meanwhile, at their home; and with feminine care Flora placed a simple repast before her brother, and then employed herself busily in making various packages. Lorenzo paced the room, absorbed in thought; at length he stopped, and, kissing the fair girl, said,—

“Where can I place thee in safety? how preserve thee, my flower of beauty, while we are divided?”

Flora looked up fearfully. “Do I not go with you?” she asked; “I was making preparations for our journey.”

“Impossible, dearest; I go to privation and hardship.”

“And I would share them with thee.”

“It may not be, sweet sister,” replied Lorenzo, “fate divides us, and we must submit. I go to camps—to the society of rude men; to struggle with such fortune as cannot harm me, but which for thee would be fraught with peril and despair. No, my Flora, I must provide safe and honourable guardianship for thee, even in this town.” And again Lorenzo meditated deeply on the part he should take, till suddenly a thought flashed on his mind. “It is hazardous,” he murmured, “and yet I do him wrong to call it so. Were our fates reversed, should I not think myself highly honoured by such a trust?” And then he told his sister to don hastily her best attire; to wrap her veil round her, and to come with him. She obeyed—for obedience to her brother was the first and dearest of her duties. But she wept bitterly while her trembling fingers braided her long hair, and she hastily changed her dress.

At length they walked forth again, and proceeded slowly, as Lorenzo employed the precious minutes in consoling and counselling his sister. He promised as speedy a return as he could accomplish; but if he failed to appear as soon as he could wish, yet he vowed solemnly that, if alive and free, she should see him within five years from the moment of parting. Should he not come before, he besought her earnestly to take patience, and to hope for the best till the expiration of that period; and made her promise not to bind herself by any vestal or matrimonial vow in the interim. They had arrived at their destination, and entered the courtyard of a spacious palace. They met no servants; so crossed the court, and ascended the ample stairs. Flora had endeavoured to listen to her brother. He had bade her be of good cheer, and he was about to leave her; he told her to hope; and he spoke of an absence to endure five years—an endless term to her youthful anticipations. She promised obedience, but her voice was choked by sobs, and her tottering limbs would not have supported her without his aid. She now perceived that they were entering the lighted and inhabited rooms of a noble dwelling, and tried to restrain her tears, as she drew her veil closely around her. They passed from room to room, in which preparations for festivity were making; the servants ushered them on, as if they had been invited guests, and conducted them into a hall filled with all the nobility and beauty of Siena. Each eye turned with curiosity and wonder on the pair. Lorenzo’s tall person, and the lofty expression of his handsome countenance, put the ladies in good-humour with him, while the cavaliers tried to peep under Flora’s veil.

“It is a mere child,” they said, “and a sorrowing one—what can this mean?”

The youthful master of the house, however, instantly recognised his uninvited and unexpected guest; but before he could ask the meaning of his coming, Lorenzo had advanced with his sister to the spot where he stood, and addressed him.

“I never thought, Count Fabian, to stand beneath your roof, and much less to approach you as a suitor. But that Supreme Power, to whose decrees we must all bend, has reduced me to such adversity as, if it be His will, may also visit you, notwithstanding the many friends that now surround you, and the sunshine of prosperity in which you bask. I stand here a banished man and a beggar. Nor do I repine at this my fate. Most willing am I that my right arm alone should create my fortunes; and, with the blessing of God, I hope so to direct my course, that we may yet meet upon more equal terms. In this hope I turn my steps, not unwillingly, from this city; dear as its name is to my heart—and dear the associations which link its proud towers with the memory of my forefathers. I leave it a soldier of fortune; how I may return is written in the page where your unread destiny is traced as well as mine. But my care ends not with myself. My dying father bequeathed to me this child, my orphan sister, whom I have, until now, watched over with a parent’s love. I should ill perform the part intrusted to me, were I to drag this tender blossom from its native bower into the rude highways of life. Lord Fabian, I can count no man my friend; for it would seem that your smiles have won the hearts of my fellow-citizens from me; and death and exile have so dealt with my house, that not one of my name exists within the walls of Siena. To you alone can I intrust this precious charge. Will you accept it until called upon to render it back to me, her brother, or to the juster hands of our Creator, pure and untarnished as I now deliver her to you? I ask you to protect her helplessness, to guard her honour; will you—dare you accept a treasure, with the assurance of restoring it unsoiled, unhurt?”

The deep expressive voice of the noble youth and his earnest eloquence enchained the ears of the whole assembly; and when he ceased, Fabian, proud of the appeal, and nothing loath in the buoyant spirit of youth to undertake a charge which, thus proffered before his assembled kinsmen and friends, became an honour, answered readily, “I agree, and solemnly before Heaven accept your offer. I declare myself the guardian and protector of your sister; she shall dwell in safety beneath my kind mother’s care, and if the saints permit your return, she shall be delivered back to you as spotless as she now is.”

Lorenzo bowed his head; something choked his utterance as he thought that he was about to part for ever from Flora; but he disdained to betray this weakness before his enemies. He took his sister’s hand and gazed upon her slight form with a look of earnest fondness, then murmuring a blessing over her, and kissing her brow, he again saluted Count Fabian, and turning away with measured steps and lofty mien, left the hall. Flora, scarcely understanding what had passed, stood trembling and weeping under her veil. She yielded her passive hand to Fabian, who, leading her to his mother, said: “Madam, I ask of your goodness, and the maternal indulgence you have ever shown, to assist me in fulfilling my promise, by taking under your gracious charge this young orphan.”

“You command here, my son,” said the countess, “and your will shall be obeyed.” Then making a sign to one of her attendants, Flora was conducted from the hall, to where, in solitude and silence, she wept over her brother’s departure, and her own strange position.

Flora thus became an inmate of the dwelling of her ancestral foes, and the ward of the most bitter enemy of her house. Lorenzo was gone she knew not whither, and her only pleasure consisted in reflecting that she was obeying his behests. Her life was uniform and tranquil. Her occupation was working tapestry, in which she displayed taste and skill. Sometimes she had the more mortifying task imposed on her of waiting on the Countess de’ Tolomei, who having lost two brothers in the last contest with the Mancini, nourished a deep hatred towards the whole race, and never smiled on the luckless orphan. Flora submitted to every command imposed upon her. She was buoyed up by the reflection that her sufferings wore imposed on her by Lorenzo; schooling herself in any moment of impatience by the idea that thus she shared his adversity. No murmur escaped her, though the pride and independence of her nature were often cruelly offended by the taunts and supercilious airs of her patroness or mistress, who was not a bad woman, but who thought it virtue to ill-treat a Mancini. Often, indeed, she neither heard nor heeded these things. Her thoughts were far away, and grief for the loss of her brother’s society weighed too heavily on her to allow her to spend more than a passing sigh on her personal injuries.

The countess was unkind and disdainful, but it was not thus with Flora’s companions. They were amiable and affectionate girls, either of the bourgeois class, or daughters of dependants of the house of Tolomei. The length of time which had elapsed since the overthrow of the Mancini, had erased from their young minds the bitter duty of hatred, and it was impossible for them to live on terms of daily intercourse with the orphan daughter of this ill-fated race, and not to become strongly attached to her. She was wholly devoid of selfishness, and content to perform her daily tasks in inoffensive silence. She had no envy, no wish to shine, no desire of pleasure. She was nevertheless ever ready to sympathize with her companions, and glad to have it in her power to administer to their happiness. To help them in the manufacture of some piece of finery; to assist them in their work; and, perfectly prudent and reserved herself, to listen to all their sentimental adventures; to give her best advice, and to aid them in any difficulty, were the simple means she used to win their unsophisticated hearts. They called her an angel; they looked up to her as to a saint, and in their hearts respected her more than the countess herself.

One only subject ever disturbed Flora’s serene melancholy. The praise she perpetually heard lavished on Count Fabian, her brother’s too successful rival and oppressor, was an unendurable addition to her other griefs. Content with her own obscurity, her ambition, her pride, her aspiring thoughts were spent upon her brother. She hated Count Fabian as Lorenzo’s destroyer, and the cause of his unhappy exile. His accomplishments she despised as painted vanities; his person she contemned as the opposite of his prototype. His blue eyes, clear and open as day; his fair complexion and light brown hair; his slight elegant person; his voice, whose tones in song won each listener’s heart to tenderness and love; his wit, his perpetual flow of spirits, and unalterable good-humour, were impertinences and frivolities to her who cherished with such dear worship the recollection of her serious, ardent, noble-hearted brother, whose soul was ever set on high thoughts, and devoted to acts of virtue and self-sacrifice; whose fortitude and affectionate courtesy seemed to her the crown and glory of manhood; how different from the trifling flippancy of Fabian! “Name an eagle,” she would say, “and we raise our eyes to heaven, there to behold a creature fashioned in Nature’s bounty; but it is a degradation to waste one thought on the insect of a day.” Some speech similar to this had been kindly reported to the young count’s lady mother, who idolized her son as the ornament and delight of his age and country. She severely reprimanded the incautious Flora, who, for the first time, listened proudly and unyieldingly. From this period her situation grew more irksome; all she could do was to endeavour to withdraw herself entirely from observation, and to brood over the perfections, while she lamented yet more keenly the absence, of her brother.

Two or three years thus flew away, and Flora grew from a childish-looking girl of twelve into the bewitching beauty of fifteen. She unclosed like a flower, whose fairest petals are yet shut, but whose half-veiled loveliness is yet more attractive. It was at this time that on occasion of doing honour to a prince of France, who was passing on to Naples, the Countess Tolomei and her son, with a bevy of friends and followers, went out to meet and to escort the royal traveller on his way. Assembled in the hall of the palace, and waiting for the arrival of some of their number, Count Fabian went round his mother’s circle, saying agreeable and merry things to all. Wherever his cheerful blue eyes lighted, there smiles were awakened and each young heart beat with vanity at his harmless flatteries. After a gallant speech or two, he espied Flora, retired behind her companions.

“What flower is this,” he said, “playing at hide and seek with her beauty?” And then, struck by the modest sweetness of her aspect, her eyes cast down, and a rosy blush mantling over her cheek, he added, “What fair angel makes one of your company?”

“An angel indeed, my lord,” exclaimed one of the younger girls, who dearly loved her best friend; “she is Flora Mancini.”

“Mancini!” exclaimed Fabian, while his manner became at once respectful and kind. “Are you the orphan daughter of Ugo—the sister of Lorenzo, committed by him to my care?” For since then, through her careful avoidance, Fabian had never even seen his fair ward. She bowed an assent to his questions, while her swelling heart denied her speech; and Fabian, going up to his mother, said, “Madam, I hope for our honour’s sake that this has not before happened. The adverse fortune of this young lady may render retirement and obscurity befitting; but it is not for us to turn into a menial one sprung from the best blood in Italy. Let me entreat you not to permit this to occur again. How shall I redeem my pledged honour, or answer to her brother for this unworthy degradation?”

“Would you have me make a friend and a companion of a Mancini?” asked the countess, with raised colour.

“I ask you not, mother, to do aught displeasing to you,” replied the young noble; “but Flora is my ward, not our servant;—permit her to retire; she will probably prefer the privacy of home, to making one among the festive crowd of her house’s enemies. If not, let the choice be hers—Say, gentle one, will you go with us or retire?”

She did not speak, but raising her soft eyes, curtsied to him and to his mother, and quitted the room; so, tacitly making her selection.

From this time Flora never quitted the more secluded apartments of the palace, nor again saw Fabian. She was unaware that he had been profuse in his eulogium on her beauty; but that while frequently expressing his interest in his ward, he rather avoided the dangerous power of her loveliness. She led rather a prison life, walking only in the palace garden when it was else deserted, but otherwise her time was at her own disposal, and no commands now interfered with her freedom. Her labours were all spontaneous. The countess seldom even saw her, and she lived among this lady’s attendants like a free boarder in a convent; who cannot quit the walls, but who is not subservient to the rules of the asylum. She was more busy than ever at her tapestry frame, because the countess prized her work; and thus she could in some degree repay the protection afforded her. She never mentioned Fabian, and always imposed silence on her companions when they spoke of him. But she did this in no disrespectful terms. “He is a generous enemy, I acknowledge,” she would say, “but still he is my enemy, and while through him my brother is an exile and a wanderer upon earth, it is painful to me to hear his name.”

After the lapse of many months spent in entire seclusion and tranquillity, a change occurred in the tenor of her life. The countess suddenly resolved to pass the Easter festival at Rome. Flora’s companions were wild with joy at the prospect of the journey, the novelty, and the entertainment they promised themselves from this visit, and pitied the dignity of their friend, which prevented her from making one in their mistress’s train; for it was soon understood that Flora was to be left behind; and she was informed that the interval of the lady’s absence was to be passed by her in a villa belonging to the family situated in a sequestered nook among the neighbouring Apennines.

The countess departed in pomp and pride on her so-called pilgrimage to the sacred city, and at the same time Flora was conveyed to her rural retreat. The villa was inhabited only by the peasant and his family, who cultivated the farm, or podere, attached to it, and the old cassiére or housekeeper. The cheerfulness and freedom of the country were delightful, and the entire solitude consonant to the habits of the meditative girl, accustomed to the confinement of the city, and the intrusive prattle of her associates. Spring was opening with all the beauty which that season showers upon favoured Italy. The almond and peach trees were in blossom; and the vine-dresser sang at his work, perched with his pruning-knife among the vines. Blossoms and flowers, in laughing plenty, graced the soil; and the trees, swelling with buds ready to expand into leaves, seemed to feel the life that animated their dark old boughs. Flora was enchanted; the country labours interested her, and the hoarded experience of old Sandra was a treasure-house of wisdom and amusement. Her attention had hitherto been directed to giving the most vivid hues and truest imitation to her transcript with her needle of some picture given her as a model; but here was a novel occupation. She learned the history of the bees, watched the habits of the birds, and inquired into the culture of plants. Sandra was delighted with her new companion; and, though notorious for being cross, yet could wriggle her antique lips into smiles for Flora.

To repay the kindness of her guardian and his mother, she still devoted much time to her needle. This occupation but engaged half her attention; and while she pursued it, she could give herself up to endless reverie on the subject of Lorenzo’s fortunes. Three years had flown since he had left her; and, except a little gold cross brought to her by a pilgrim from Milan, but one month after his departure, she had received no tidings of him. Whether from Milan he had proceeded to France, Germany, or the Holy Land, she did not know. By turns her fancy led him to either of these places, and fashioned the course of events that might have befallen him. She figured to herself his toilsome journeys—his life in the camp—his achievements, and the honours showered on him by kings and nobles; her cheek glowed at the praises he received, and her eye kindled with delight as it imaged him standing with modest pride and an erect but gentle mien before them. Then the fair enthusiast paused; it crossed her recollection like a shadow, that if all had gone prosperously, he had returned to share his prosperity with her, and her faltering heart turned to sadder scenes to account for his protracted absence.

Sometimes, while thus employed, she brought her work into the trellised arbour of the garden, or, when it was too warm for the open air, she had a favourite shady window, which looked down a deep ravine into a majestic wood, whence the sound of falling water met her ears. One day, while she employed her fingers upon the spirited likeness of a hound which made a part of the hunting-piece she was working for the countess, a sharp, wailing cry suddenly broke on her ear, followed by trampling of horses and the hurried steps and loud vociferations of men. They entered the villa on the opposite side from that which her window commanded; but, the noise continuing, she rose to ask the reason, when Sandra burst into the room, crying, “O Madonna! he is dead! he has been thrown from his horse, and he will never speak more.” Flora for an instant could only think of her brother. She rushed past the old woman, down into the great hall, in which, lying on a rude litter of boughs, she beheld the inanimate body of Count Fabian. He was surrounded by servitors and peasants, who were all clasping their hands and tearing their hair as, with frightful shrieks, they pressed round their lord, not one of them endeavouring to restore him to life. Flora’s first impulse was to retire; but, casting a second glance on the livid brow of the young count, she saw his eyelids move, and the blood falling in quick drops from his hair on the pavement. She exclaimed, “He is not dead—he bleeds! hasten some of you for a leech!” And meanwhile she hurried to get some water, sprinkled it on his face, and, dispersing the group that hung over him and impeded the free air, the soft breeze playing on his forehead revived him, and he gave manifest tokens of life; so that when the physician arrived, he found that, though he was seriously and even dangerously hurt, every hope might be entertained of his recovery.

Flora undertook the office of his nurse, and fulfilled its duties with unwearied attention. She watched him by night and waited on him by day with that spirit of Christian humility and benevolence which animates a Sister of Charity as she tends the sick. For several days Fabian’s soul seemed on the wing to quit its earthly abode; and the state of weakness that followed his insensibility was scarcely less alarming. At length, he recognised and acknowledged the care of Flora, but she alone possessed any power to calm and guide him during the state of irritability and fever that then ensued. Nothing except her presence controlled his impatience; before her he was so lamb-like, that she could scarcely have credited the accounts that others gave her of his violence, but that, whenever she returned, after leaving him for any time, she heard his voice far off in anger, and found him with flushed cheeks and flashing eyes, all which demonstrations subsided into meek acquiescence when she drew near.

In a few weeks he was able to quit his room; but any noise or sudden sound drove him almost insane. So loud is an Italian’s quietest movements, that Flora was obliged to prevent the approach of any except herself; and her soft voice and noiseless footfall were the sweetest medicine she could administer to her patient. It was painful to her to be in perpetual attendance on Lorenzo’s rival and foe, but she subdued her heart to her duty, and custom helped to reconcile her. As he grew better, she could not help remarking the intelligence of his countenance, and the kindness and cordiality of his manners. There was an unobtrusive and delicate attention and care in his intercourse with her that won her to be pleased. When he conversed, his discourse was full of entertainment and variety. His memory was well-stored with numerous fabliaux, novelle, and romances, which he quickly discovered to be highly interesting to her, and so contrived to have one always ready from the exhaustless stock he possessed. These romantic stories reminded her of the imaginary adventures she had invented, in solitude and silence, for her brother; and each tale of foreign countries had a peculiar charm, which animated her face as she listened, so that Fabian could have gone on for ever, only to mark the varying expression of her countenance as he proceeded. Yet she acknowledged these attractions in him as a Catholic nun may the specious virtues of a heretic; and, while he contrived each day to increase the pleasure she derived from his society, she satisfied her conscience with regard to her brother by cherishing in secret a little quiet stock of family hate, and by throwing over her manners, whenever she could recollect so to do, a cold and ceremonious tone, which she had the pleasure of seeing vexed him heartily.

Nearly two months had passed, and he was so well recovered that Flora began to wonder that he did not return to Siena, and of course to fulfil her duty by wishing that he should; and yet, while his cheek was sunk through past sickness, and his elastic step grown slow, she, as a nurse desirous of completing her good work, felt averse to his entering too soon on the scene of the busy town and its noisy pleasures. At length, two or three of his friends having come to see him, he agreed to return with them to the city. A significant glance which they cast on his young nurse probably determined him. He parted from her with a grave courtesy and a profusion of thanks, unlike his usual manner, and rode off without alluding to any probability of their meeting again.

S he fancied that she was relieved from a burden when he went, and was surprised to find the days grow tedious, and mortified to perceive that her thoughts no longer spent themselves so spontaneously on her brother, and to feel that the occupation of a few weeks could unhinge her mind and dissipate her cherished reveries; thus, while she felt the absence of Fabian, she was annoyed at him the more for having, in addition to his other misdeeds, invaded the sanctuary of her dearest thoughts. She was beginning to conquer this listlessness, and to return with renewed zest to her usual occupations, when, in about a week after his departure, Fabian suddenly returned. He came upon her as she was gathering flowers for the shrine of the Madonna; and, on seeing him, she blushed as rosy red as the roses she held. He looked infinitely worse in health than when he went. His wan cheeks and sunk eyes excited her concern; and her earnest and kind questions somewhat revived him. He kissed her hand, and continued to stand beside her as she finished her nosegay. Had any one seen the glad, fond look with which he regarded her as she busied herself among the flowers, even old Sandra might have prognosticated his entire recovery under her care.

he fancied that she was relieved from a burden when he went, and was surprised to find the days grow tedious, and mortified to perceive that her thoughts no longer spent themselves so spontaneously on her brother, and to feel that the occupation of a few weeks could unhinge her mind and dissipate her cherished reveries; thus, while she felt the absence of Fabian, she was annoyed at him the more for having, in addition to his other misdeeds, invaded the sanctuary of her dearest thoughts. She was beginning to conquer this listlessness, and to return with renewed zest to her usual occupations, when, in about a week after his departure, Fabian suddenly returned. He came upon her as she was gathering flowers for the shrine of the Madonna; and, on seeing him, she blushed as rosy red as the roses she held. He looked infinitely worse in health than when he went. His wan cheeks and sunk eyes excited her concern; and her earnest and kind questions somewhat revived him. He kissed her hand, and continued to stand beside her as she finished her nosegay. Had any one seen the glad, fond look with which he regarded her as she busied herself among the flowers, even old Sandra might have prognosticated his entire recovery under her care.

Flora was totally unaware of the feelings that were excited in Fabian’s heart, and the struggle he made to overcome a passion too sweet and too seductive, when awakened by so lovely a being, ever to be subdued. He had been struck with her some time ago, and avoided her. It was through his suggestion that she passed the period of the countess’s pilgrimage in this secluded villa. Nor had he thought of visiting her there; but, riding over one day to inquire concerning a foal rearing for him, his horse had thrown him, and caused him that injury which had made him so long the inmate of the same abode. Already prepared to admire her—her kindness, her gentleness, and her unwearied patience during his illness, easily conquered a heart most ready and yet most unwilling to yield. He had returned to Siena resolved to forget her, but he came back assured that his life and death were in her hands.

At first Count Fabian had forgot that he had any but his own feelings and prejudices, and those of his mother and kindred, to overcome; but when the tyranny of love vanquished these, he began to fear a more insurmountable impediment in Flora. The first whisper of love fell like mortal sin upon her ear; and disturbed, and even angry, she replied:—

“Methinks you wholly forget who I am, and what you are. I speak not of ancient feuds, though these were enough to divide us for ever. Know that I hate you as my brother’s oppressor. Restore Lorenzo to me—recall him from banishment—erase the memory of all that he has suffered through you—win his love and approbation;—and when all this is fulfilled, which never can be, speak a language which now it is as the bitterness of death for me to hear!”

And saying this, she hastily retired, to conceal the floods of tears which this, as she termed it, insult had caused to flow; to lament yet more deeply her brother’s absence and her own dependence.

Fabian was not so easily silenced; and Flora had no wish to renew scenes and expressions of violence so foreign to her nature. She imposed a rule on herself, by never swerving from which she hoped to destroy the ill-omened love of her protector. She secluded herself as much as possible; and when with him assumed a chilling indifference of manner, and made apparent in her silence so absolute and cold a rejection of all his persuasions, that had not love with its unvanquishable hopes reigned absolutely in young Fabian’s heart, he must have despaired. He ceased to speak of his affection, so to win back her ancient kindness. This was at first difficult; for she was timid as a young bird, whose feet have touched the limed twigs. But naturally credulous, and quite inexperienced, she soon began to believe that her alarm was exaggerated, and to resume those habits of intimacy which had heretofore subsisted between them. By degrees Fabian contrived to insinuate the existence of his attachment—he could not help it. He asked no return; he would wait for Lorenzo’s arrival, which he was sure could not be far distant. Her displeasure could not change, nor silence destroy, a sentiment which survived in spite of both. Intrenched in her coldness and her indifference, she hoped to weary him out by her defensive warfare, and fancied that he would soon cease his pursuit in disgust.

The countess had been long away; she had proceeded to view the feast of San Gennaro at Naples, and had not received tidings of her son’s illness. Her return was now expected; and Fabian resolved to return to Siena in time to receive her. Both he and Flora were therefore surprised one day, when she suddenly entered the apartment where they both were. Flora had long peremptorily insisted that he should not intrude while she was employed on her embroidery frame; but this day he had made so good a pretext, that for the first time he was admitted, and then suffered to stay a few minutes—they now neither of them knew how long; she was busy at her work; and he sitting near, gazing unreproved on her unconscious face and graceful figure, felt himself happier than he had ever been before.

The countess was sufficiently surprised, and not a little angry; but before she could do more than utter one exclamation, Fabian interrupted, by entreating her not to spoil all. He drew her away; he made his own explanations, and urged his wishes with resistless persuasion. The countess had been used to indulge him in every wish; it was impossible for her to deny any strongly urged request; his pertinacity, his agitation, his entreaties half won her; and the account of his illness, and his assurances, seconded by those of all the family, that Flora had saved his life, completed the conquest, and she became in her turn a suitor for her son to the orphan daughter of Mancini.

Flora, educated till the age of twelve by one who never consulted his own pleasures and gratifications, but went right on in the path of duty, regardless of pain or disappointment, had no idea of doing aught merely because she or others might wish it. Since that time she had been thrown on her own resources; and jealously cherishing her individuality, every feeling of her heart had been strengthened by solitude and by a sense of mental independence. She was the least likely of any one to go with the stream, or to yield to the mere influence of circumstances. She felt, she knew, what it became her to do, and that must be done in spite of every argument.

The countess’s expostulations and entreaties were of no avail. The promise she had made to her brother of engaging herself by no vow for five years must be observed under every event; it was asked from her at the sad and solemn hour of their parting, and was thus rendered doubly sacred. So constituted, indeed, were her feelings, that the slightest wish she ever remembered having been expressed by Lorenzo had more weight with her than the most urgent prayers of another. He was a part of her religion; reverence and love for him had been moulded into the substance of her soul from infancy; their very separation had tended to render these impressions irradicable. She brooded over them for years; and when no sympathy or generous kindness was afforded her—when the countess treated her like an inferior and a dependant, and Fabian had forgotten her existence, she had lived from month to month, and from year to year, cherishing the image of her brother, and only able to tolerate the annoyances that beset her existence, by considering that her patience, her fortitude, and her obedience were all offerings at the shrine of her beloved Lorenzo’s desires.

It is true that the generous and kindly disposition of Fabian won her to regard him with a feeling nearly approaching tenderness, though this emotion was feeble, the mere ripple of the waves, compared to the mighty tide of affection that set her will all one way, and made her deem everything trivial except Lorenzo’s return—Lorenzo’s existence—obedience to Lorenzo. She listened to her lover’s persuasions so unyieldingly that the countess was provoked by her inflexibility; but she bore her reproaches with such mildness, and smiled so sweetly, that Fabian was the more charmed. She admitted that she owed him a certain submission as the guardian set over her by her brother; Fabian would have gladly exchanged this authority for the pleasure of being commanded by her; but this was an honour he could not attain, so in playful spite he enforced concessions from her. At his desire she appeared in society, dressed as became her rank, and filled in his house the station a sister of his own would have held. She preferred seclusion, but she was averse to contention, and it was little that she yielded, while the purpose of her soul was as fixed as ever.

The fifth year of Lorenzo’s exile was now drawing to a close, but he did not return, nor had any intelligence been received of him. The decree of his banishment had been repealed, the fortunes of his house restored, and his palace, under Fabian’s generous care, rebuilt. These were acts that demanded and excited Flora’s gratitude; yet they were performed in an unpretending manner, as if the citizens of Siena had suddenly become just and wise without his interference. But these things dwindled into trifles while the continuation of Lorenzo’s absence seemed the pledge of her eternal misery; and the tacit appeal made to her kindness, while she had no thought but for her brother, drove her to desperation. She could no longer tolerate the painful anomaly of her situation; she could not endure her suspense for her brother’s fate, nor the reproachful glances of Fabian’s mother and his friends. He himself was more generous,—he read her heart, and, as the termination of the fifth year drew nigh, ceased to allude to his own feelings, and appeared as wrapt as herself in doubt concerning the fate of the noble youth, whom they could scarcely entertain a hope of ever seeing more. This was small comfort to Flora. She had resolved that when the completion of the fifth year assured her that her brother was for ever lost, she would never see Fabian again. At first she had resolved to take refuge in a convent, and in the sanctity of religious vows. But she remembered how averse Lorenzo had always shown himself to this vocation, and that he had preferred to place her beneath the roof of his foe, than within the walls of a nunnery. Besides, young as she was, and, despite of herself, full of hope, she recoiled from shutting the gates of life upon herself for ever. Notwithstanding her fears and sorrow, she clung to the belief that Lorenzo lived; and this led her to another plan. When she had received her little cross from Milan, it was accompanied by a message that he believed he had found a good friend in the archbishop of that place. This prelate, therefore, would know whither Lorenzo had first bent his steps, and to him she resolved to apply. Her scheme was easily formed. She possessed herself of the garb of a pilgrim, and resolved on the day following the completion of the fifth year to depart from Siena, and bend her steps towards Lombardy, buoyed up by the hope that she should gain some tidings of her brother.

Meanwhile Fabian had formed a similar resolve. He had learnt the fact from Flora, of Lorenzo having first resorted to Milan, and he determined to visit that city, and not to return without certain information. He acquainted his mother with his plan, but begged her not to inform Flora, that she might not be tortured by double doubt during his absence.

The anniversary of the fifth year was come, and with it the eve of these several and separate journeys. Flora had retired to spend the day at the villa before mentioned. She had chosen to retire thither for various reasons. Her escape was more practicable thence than in the town; and she was anxious to avoid seeing both Fabian and his mother, now that she was on the point of inflicting severe pain on them. She spent the day at the villa and in its gardens, musing on her plans, regretting the quiet of her past life—saddened on Fabian’s account—grieving bitterly for Lorenzo. She was not alone, for she had been obliged to confide in one of her former companions, and to obtain her assistance. Poor little Angeline was dreadfully frightened with the trust reposed in her, but did not dare expostulate with or betray her friend; and she continued near her during this last day, by turns trying to console and weeping with her. Towards evening they wandered together into the wood contiguous to the villa. Flora had taken her harp with her, but her trembling fingers refused to strike its chords; she left it, she left her companion, and strayed on alone to take leave of a spot consecrated by many a former visit. Here the umbrageous trees gathered about her, and shaded her with their thick and drooping foliage;—a torrent dashed down from neighbouring rock, and fell from a height into a rustic basin, hollowed to receive it; then, overflowing the margin at one spot, it continued falling over successive declivities, till it reached the bottom of a little ravine, when it stole on in a placid and silent course. This had ever been a favourite resort of Flora. The twilight of the wood and the perpetual flow, the thunder, the hurry, and the turmoil of the waters, the varied sameness of the eternal elements, accorded with the melancholy of her ideas, and the endless succession of her reveries. She came to it now; she gazed on the limpid cascade—for the last time; a soft sadness glistened in her eyes, and her attitude denoted the tender regret that filled her bosom; her long bright tresses streaming in elegant disorder, her light veil and simple, yet rich, attire, were fitfully mirrored in the smooth face of the rushing waters. At this moment the sound of steps more firm and manly than those of Angeline struck her ear, and Fabian himself stood before her; he was unable to bring himself to depart on his journey without seeing her once again. He had ridden to the villa, and, finding that she had quitted it, sought and found her in the lone recess where they had often spent hours together which had been full of bliss to him. Flora was sorry to see him, for her secret was on her lips, and yet she resolved not to give it utterance. He was ruled by the same feeling. Their interview was therefore short, and neither alluded to what sat nearest the heart of each. They parted with a simple “Good-night,” as if certain of meeting the following morning; each deceived the other, and each was in turn deceived. There was more of tenderness in Flora’s manner than there had ever been; it cheered his faltering soul, about to quit her, while the anticipation of the blow he was about to receive from her made her regard as venial this momentary softening towards her brother’s enemy.

Fabian passed the night at the villa, and early the next morning he departed for Milan. He was impatient to arrive at the end of his journey, and often he thrust his spurs into his horse’s sides, and put him to his speed, which even then appeared slow. Yet he was aware that his arrival at Milan might advance him not a jot towards the ultimate object of his journey; and he called Flora cruel and unkind, until the recollection of her kind farewell consoled and cheered him.

He stopped the first night at Empoli, and, crossing the Arno, began to ascend the Apennines on the northern side. Soon he penetrated their fastnesses, and entered deep into the ilex woods. He journeyed on perseveringly, and yet the obstructions he met with were many, and borne with impatience. At length, on the afternoon of the third day, he arrived at a little rustic inn, hid deep in a wood, which showed signs of seldom being visited by travellers. The burning sun made it a welcome shelter for Fabian; and he deposited his steed in the stable, which he found already partly occupied by a handsome black horse, and then entered the inn to seek refreshment for himself. There seemed some difficulty in obtaining this. The landlady was the sole domestic, and it was long before she made her appearance, and then she was full of trouble and dismay; a sick traveller had arrived—a gentleman to all appearance dying of a malignant fever. His horse, his well-stored purse, and rich dress showed that he was a cavalier of consequence;—the more the pity. There was no help, nor any means of carrying him forward; yet half his pain seemed to arise from his regret at being detained—he was so eager to proceed to Siena. The name of his own town excited the interest of Count Fabian, and he went up to visit the stranger, while the hostess prepared his repast.

Meanwhile Flora awoke with the lark, and with the assistance of Angeline attired herself in her pilgrim’s garb. From the stir below, she was surprised to find that Count Fabian had passed the night at the villa, and she lingered till he should have departed, as she believed, on his return to Siena. Then she embraced her young friend, and taking leave of her with many blessings and thanks, alone, with Heaven, as she trusted, for her guide, she quitted Fabian’s sheltering roof, and with a heart that maintained its purpose in spite of her feminine timidity, began her pilgrimage. Her journey performed on foot was slow, so that there was no likelihood that she could overtake her lover, already many miles in advance. Now that she had begun it, her undertaking appeared to her gigantic, and her heart almost failed her. The burning sun scorched her; never having before found herself alone in a highway, a thousand fears assailed her, and she grew so weary, that soon she was unable to support herself. By the advice of a landlady at an inn where she stopped, she purchased a mule to help her on her long journey. Yet with this help it was the third night before she arrived at Empoli, and then crossing the Arno, as her lover had done before, her difficulties seemed to begin to unfold themselves, and to grow gigantic, as she entered the dark woods of the Apennines, and found herself amidst the solitude of its vast forests. Her pilgrim’s garb inspired some respect, and she rested at convents by the way. The pious sisters held up their hands in admiration of her courage; while her heart beat faintly with the knowledge that she possessed absolutely none. Yet, again and again, she repeated to herself, that the Apennines once passed, the worst would be over. So she toiled on, now weary, now frightened—very slowly, and yet very anxious to get on with speed.

On the evening of the seventh day after quitting her home, she was still entangled in the mazes of these savage hills. She was to sleep at a convent on their summit that night, and the next day arrive at Bologna. This hope had cheered her through the day; but evening approached, the way grew more intricate, and no convent appeared. The sun had set, and she listened anxiously for the bell of the Ave Maria, which would give her hope that the goal she sought was nigh; but all was silent, save the swinging boughs of the vast trees, and the timid beating of her own heart; darkness closed around her, and despair came with the increased obscurity, till a twinkling light, revealing itself among the trees, afforded her some relief. She followed this beamy guide till it led her to a little inn, where the sight of a kind-looking woman, and the assurance of safe shelter, dispelled her terrors, and filled her with grateful pleasure.

Seeing her so weary, the considerate hostess hastened to place food before her, and then conducted her to a little low room where her bed was prepared. “I am sorry, lady,” said the landlady in a whisper, “not to be able to accommodate you better; but a sick cavalier occupies my best room—it is next to this—and he sleeps now, and I would not disturb him. Poor gentleman! I never thought he would rise more; and under Heaven he owes his life to one who, whether he is related to him or not I cannot tell, for he did not accompany him. Four days ago he stopped here, and I told him my sorrow—how I had a dying guest, and he charitably saw him, and has since then nursed him more like a twin-brother than a stranger.”

The good woman prattled on. Flora heard but little of what she said; and overcome by weariness and sleep, paid no attention to her tale. But having performed her orisons, and placed her head on the pillow, she was quickly lapped in the balmy slumber she so much needed.

Early in the morning she was awoke by a murmur of voices in the next room. She started up, and recalling her scattered thoughts, tried to remember the account the hostess had given her the preceding evening. The sick man spoke, but his accent was low, and the words did not reach her;—he was answered—could Flora believe her senses? did she not know the voice that spoke these words?—“Fear nothing, a sweet sleep has done you infinite good; and I rejoice in the belief that you will speedily recover. I have sent to Siena for your sister, and do indeed expect that Flora will arrive this very day.”

More was said, but Flora heard no more; she had risen, and was hastily dressing herself; in a few minutes she was by her brother’s, her Lorenzo’s bedside, kissing his wan hand, and assuring him that she was indeed Flora.

“These are indeed wonders,” he at last said; “and if you are mine own Flora you perhaps can tell me who this noble gentleman is, who day and night has watched beside me, as a mother may by her only child, giving no time to repose, but exhausting himself for me.”

“How, dearest brother,” said Flora, “can I truly answer your question? to mention the name of our benefactor were to speak of a mask and a disguise, not a true thing. He is my protector and guardian, who has watched over and preserved me while you wandered far; his is the most generous heart in Italy, offering past enmity and family pride as sacrifices at the altar of nobleness and truth. He is the restorer of your fortunes in your native town”—

“And the lover of my sweet sister.—I have heard of these things, and was on my way to confirm his happiness and to find my own, when sickness laid me thus low, and would have destroyed us both for ever, but for Fabian Tolomei”—

“Who how exerts his expiring authority to put an end to this scene,” interrupted the young count. “Not till this day has Lorenzo been sufficiently composed to hear any of these explanations, and we risk his returning health by too long a conversation. The history of these things and of his long wanderings, now so happily ended, must be reserved for a future hour; when assembled in our beloved Siena, exiles and foes no longer, we shall long enjoy the happiness which Providence, after so many trials, has bounteously reserved for us.”

Mary Shelley

(1797 – 1851)

The Brother and Sister: An Italian Story harkens to the familiar tragedy of feuding families, Romeo and Juliet.

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Mary Shelley, Shelley, Mary, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Sredni Vashtar

Conradin was ten years old, and the doctor had pronounced his professional opinion that the boy would not live another five years. The doctor was silky and effete, and counted for little, but his opinion was endorsed by Mrs. de Ropp, who counted for nearly everything. Mrs. De Ropp was Conradin’s cousin and guardian, and in his eyes she represented those three-fifths of the world that are necessary and disagreeable and real; the other two-fifths, in perpetual antagonism to the foregoing, were summed up in himself and his imagination. One of these days Conradin supposed he would succumb to the mastering pressure of wearisome necessary things — such as illnesses and coddling restrictions and drawn-out dullness. Without his imagination, which was rampant under the spur of loneliness, he would have succumbed long ago.

Mrs. de Ropp would never, in her honestest moments, have confessed to herself that she disliked Conradin, though she might have been dimly aware that thwarting him “for his good” was a duty which she did not find particularly irksome. Conradin hated her with a desperate sincerity which he was perfectly able to mask. Such few pleasures as he could contrive for himself gained an added relish from the likelihood that they would be displeasing to his guardian, and from the realm of his imagination she was locked out — an unclean thing, which should find no entrance.

Mrs. de Ropp would never, in her honestest moments, have confessed to herself that she disliked Conradin, though she might have been dimly aware that thwarting him “for his good” was a duty which she did not find particularly irksome. Conradin hated her with a desperate sincerity which he was perfectly able to mask. Such few pleasures as he could contrive for himself gained an added relish from the likelihood that they would be displeasing to his guardian, and from the realm of his imagination she was locked out — an unclean thing, which should find no entrance.

In the dull, cheerless garden, overlooked by so many windows that were ready to open with a message not to do this or that, or a reminder that medicines were due, he found little attraction. The few fruit-trees that it contained were set jealously apart from his plucking, as though they were rare specimens of their kind blooming in an arid waste; it would probably have been difficult to find a market-gardener who would have offered ten shillings for their entire yearly produce. In a forgotten corner, however, almost hidden behind a dismal shrubbery, was a disused tool-shed of respectable proportions, and within its walls Conradin found a haven, something that took on the varying aspects of a playroom and a cathedral. He had peopled it with a legion of familiar phantoms, evoked partly from fragments of history and partly from his own brain, but it also boasted two inmates of flesh and blood. In one corner lived a ragged-plumaged Houdan hen, on which the boy lavished an affection that had scarcely another outlet. Further back in the gloom stood a large hutch, divided into two compartments, one of which was fronted with close iron bars. This was the abode of a large polecat-ferret, which a friendly butcher-boy had once smuggled, cage and all, into its present quarters, in exchange for a long-secreted hoard of small silver. Conradin was dreadfully afraid of the lithe, sharp-fanged beast, but it was his most treasured possession. Its very presence in the tool-shed was a secret and fearful joy, to be kept scrupulously from the knowledge of the Woman, as he privately dubbed his cousin. And one day, out of Heaven knows what material, he spun the beast a wonderful name, and from that moment it grew into a god and a religion. The Woman indulged in religion once a week at a church near by, and took Conradin with her, but to him the church service was an alien rite in the House of Rimmon. Every Thursday, in the dim and musty silence of the tool-shed, he worshipped with mystic and elaborate ceremonial before the wooden hutch where dwelt Sredni Vashtar, the great ferret. Red flowers in their season and scarlet berries in the winter-time were offered at his shrine, for he was a god who laid some special stress on the fierce impatient side of things, as opposed to the Woman’s religion, which, as far as Conradin could observe, went to great lengths in the contrary direction. And on great festivals powdered nutmeg was strewn in front of his hutch, an important feature of the offering being that the nutmeg had to be stolen. These festivals were of irregular occurrence, and were chiefly appointed to celebrate some passing event. On one occasion, when Mrs. de Ropp suffered from acute toothache for three days, Conradin kept up the festival during the entire three days, and almost succeeded in persuading himself that Sredni Vashtar was personally responsible for the toothache. If the malady had lasted for another day the supply of nutmeg would have given out.

The Houdan hen was never drawn into the cult of Sredni Vashtar. Conradin had long ago settled that she was an Anabaptist. He did not pretend to have the remotest knowledge as to what an Anabaptist was, but he privately hoped that it was dashing and not very respectable. Mrs. de Ropp was the ground plan on which he based and detested all respectability.

After a while Conradin’s absorption in the tool-shed began to attract the notice of his guardian. “It is not good for him to be pottering down there in all weathers,” she promptly decided, and at breakfast one morning she announced that the Houdan hen had been sold and taken away overnight. With her short-sighted eyes she peered at Conradin, waiting for an outbreak of rage and sorrow, which she was ready to rebuke with a flow of excellent precepts and reasoning. But Conradin said nothing: there was nothing to be said. Something perhaps in his white set face gave her a momentary qualm, for at tea that afternoon there was toast on the table, a delicacy which she usually banned on the ground that it was bad for him; also because the making of it “gave trouble,” a deadly offence in the middle-class feminine eye.

“I thought you liked toast,” she exclaimed, with an injured air, observing that he did not touch it.

“Sometimes,” said Conradin.

In the shed that evening there was an innovation in the worship of the hutch-god. Conradin had been wont to chant his praises, to-night he asked a boon.

“Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar.”

The thing was not specified. As Sredni Vashtar was a god he must be supposed to know. And choking back a sob as he looked at that other empty corner, Conradin went back to the world he so hated.

And every night, in the welcome darkness of his bedroom, and every evening in the dusk of the tool-shed, Conradin’s bitter litany went up: “Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar.”

Mrs. de Ropp noticed that the visits to the shed did not cease, and one day she made a further journey of inspection.

“What are you keeping in that locked hutch?” she asked. “I believe it’s guinea-pigs. I’ll have them all cleared away.”

Conradin shut his lips tight, but the Woman ransacked his bedroom till she found the carefully hidden key, and forthwith marched down to the shed to complete her discovery. It was a cold afternoon, and Conradin had been bidden to keep to the house. From the furthest window of the dining-room the door of the shed could just be seen beyond the corner of the shrubbery, and there Conradin stationed himself. He saw the Woman enter, and then he imagined her opening the door of the sacred hutch and peering down with her short-sighted eyes into the thick straw bed where his god lay hidden. Perhaps she would prod at the straw in her clumsy impatience. And Conradin fervently breathed his prayer for the last time. But he knew as he prayed that he did not believe. He knew that the Woman would come out presently with that pursed smile he loathed so well on her face, and that in an hour or two the gardener would carry away his wonderful god, a god no longer, but a simple brown ferret in a hutch. And he knew that the Woman would triumph always as she triumphed now, and that he would grow ever more sickly under her pestering and domineering and superior wisdom, till one day nothing would matter much more with him, and the doctor would be proved right. And in the sting and misery of his defeat, he began to chant loudly and defiantly the hymn of his threatened idol:

Sredni Vashtar went forth,

His thoughts were red thoughts and his teeth were white.

His enemies called for peace, but he brought them death.

Sredni Vashtar the Beautiful.

And then of a sudden he stopped his chanting and drew closer to the window-pane. The door of the shed still stood ajar as it had been left, and the minutes were slipping by. They were long minutes, but they slipped by nevertheless. He watched the starlings running and flying in little parties across the lawn; he counted them over and over again, with one eye always on that swinging door. A sour-faced maid came in to lay the table for tea, and still Conradin stood and waited and watched. Hope had crept by inches into his heart, and now a look of triumph began to blaze in his eyes that had only known the wistful patience of defeat. Under his breath, with a furtive exultation, he began once again the paean of victory and devastation. And presently his eyes were rewarded: out through that doorway came a long, low, yellow-and-brown beast, with eyes a-blink at the waning daylight, and dark wet stains around the fur of jaws and throat. Conradin dropped on his knees. The great polecat-ferret made its way down to a small brook at the foot of the garden, drank for a moment, then crossed a little plank bridge and was lost to sight in the bushes. Such was the passing of Sredni Vashtar.

“Tea is ready,” said the sour-faced maid; “where is the mistress?”

“She went down to the shed some time ago,” said Conradin.