Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Three and One are One

In the year 1861 Barr Lassiter, a young man of twenty-two, lived with his parents and an elder sister near Carthage, Tennessee. The family were in somewhat humble circumstances, subsisting by cultivation of a small and not very fertile plantation. Owning no slaves, they were not rated among “the best people” of their neighborhood; but they were honest persons of good education, fairly well mannered and as respectable as any family could be if uncredentialed by personal dominion over the sons and daughters of Ham.

The elder Lassiter had that severity of manner that so frequently affirms an uncompromising devotion to duty, and conceals a warm and affectionate disposition. He was of the iron of which martyrs are made, but in the heart of the matrix had lurked a nobler metal, fusible at a milder heat, yet never coloring nor softening the hard exterior. By both heredity and environment something of the man’s inflexible character had touched the other members of the family; the Lassiter home, though not devoid of domestic affection, was a veritable citadel of duty, and duty—ah, duty is as cruel as death!

The elder Lassiter had that severity of manner that so frequently affirms an uncompromising devotion to duty, and conceals a warm and affectionate disposition. He was of the iron of which martyrs are made, but in the heart of the matrix had lurked a nobler metal, fusible at a milder heat, yet never coloring nor softening the hard exterior. By both heredity and environment something of the man’s inflexible character had touched the other members of the family; the Lassiter home, though not devoid of domestic affection, was a veritable citadel of duty, and duty—ah, duty is as cruel as death!

When the war came on it found in the family, as in so many others in that State, a divided sentiment; the young man was loyal to the Union, the others savagely hostile. This unhappy division begot an insupportable domestic bitterness, and when the offending son and brother left home with the avowed purpose of joining the Federal army not a hand was laid in his, not a word of farewell was spoken, not a good wish followed him out into the world whither he went to meet with such spirit as he might whatever fate awaited him.

Making his way to Nashville, already occupied by the Army of General Buell, he enlisted in the first organization that he found, a Kentucky regiment of cavalry, and in due time passed through all the stages of military evolution from raw recruit to experienced trooper. A right good trooper he was, too, although in his oral narrative from which this tale is made there was no mention of that; the fact was learned from his surviving comrades. For Barr Lassiter has answered “Here” to the sergeant whose name is Death.

Two years after he had joined it his regiment passed through the region whence he had come. The country thereabout had suffered severely from the ravages of war, having been occupied alternately (and simultaneously) by the belligerent forces, and a sanguinary struggle had occured in the immediate vicinity of the Lassiter homestead. But of this the young trooper was not aware.

Finding himself in camp near his home, he felt a natural longing to see his parents and sister, hoping that in them, as in him, the unnatural animosities of the period had been softened by time and separation. Obtaining a leave of absence, he set foot in the late summer afternoon, and soon after the rising of the full moon was walking up the gravel path leading to the dwelling in which he had been born.

Soldiers in war age rapidly, and in youth two years are a long time. Barr Lassiter felt himself an old man, and had almost expected to find the place a ruin and a desolation. Nothing, apparently, was changed. At the sight of each dear and familiar object he was profoundly affected. His heart beat audibly, his emotion nearly suffocated him; an ache was in his throat. Unconsciously he quickened his pace until he almost ran, his long shadow making grotesque efforts to keep its place beside him.

The house was unlighted, the door open. As he approached and paused to recover control of himself his father came out and stood bare-headed in the moonlight.

“Father!” cried the young man, springing forward with outstretched hand—“Father!”

The elder man looked him sternly in the face, stood a moment motionless and without a word withdrew into the house. Bitterly disappointed, humiliated, inexpressibly hurt and altogether unnerved, the soldier dropped upon a rustic seat in deep dejection, supporting his head upon his trembling hand. But he would not have it so: he was too good a soldier to accept repulse as defeat. He rose and entered the house, passing directly to the “sitting-room.”

It was dimly lighted by an uncurtained east window. On a low stool by the hearthside, the only article of furniture in the place, sat his mother, staring into a fireplace strewn with blackened embers and cold ashes. He spoke to her—tenderly, interrogatively, and with hesitation, but she neither answered, nor moved, nor seemed in any way surprised. True, there had been time for her husband to apprise her of their guilty son’s return. He moved nearer and was about to lay his hand upon her arm, when his sister entered from an adjoining room, looked him full in the face, passed him without a sign of recognition and left the room by a door that was partly behind him. He had turned his head to watch her, but when she was gone his eyes again sought his mother. She too had left the place.

Barr Lassiter strode to the door by which he had entered. The moonlight on the lawn was tremulous, as if the sward were a rippling sea. The trees and their black shadows shook as in a breeze. Blended with its borders, the gravel walk seemed unsteady and insecure to step on. This young soldier knew the optical illusions produced by tears. He felt them on his cheek, and saw them sparkle on the breast of his trooper’s jacket. He left the house and made his way back to camp.

The next day, with no very definite intention, with no dominant feeling that he could rightly have named, he again sought the spot. Within a half-mile of it he met Bushrod Albro, a former playfellow and schoolmate, who greeted him warmly.

“I am going to visit my home,” said the soldier.The other looked at him rather sharply, but said nothing.

“I know,” continued Lassister, “that my folks have not changed, but—”

There have been changes,” Albro interrupted—“everything changes. I’ll go with you if you don’t mind. We can talk as we go.”

But Albro did not talk.

Instead of a house they found only fire-blackened foundations of stone, enclosing an area of compact ashes pitted by rains.

Lassiter’s astonishment was extreme.

“I could not find the right way to tell you,” said Albro. “In the fight a year ago your house was burned by a Federal shell.”

“And my family—where are they?”

“In Heaven, I hope. All were killed by the shell.”

Ambrose Bierce

(1842 – 1913/1914 ?)

Three and One are One

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bierce, Ambrose, Bierce, Ambrose

Sisina

Imaginez Diane en galant équipage,

Parcourant les forêts ou battant les halliers,

Cheveux et gorge au vent, s’enivrant de tapage,

Superbe et défiant les meilleurs cavaliers!

Avez-vous vu Théroigne, amante du carnage,

Excitant à l’assaut un peuple sans souliers,

La joue et l’oeil en feu, jouant son personnage,

Et montant, sabre au poing, les royaux escaliers?

Telle la Sisina! Mais la douce guerrière

À l’âme charitable autant que meurtrière;

Son courage, affolé de poudre et de tambours,

Devant les suppliants sait mettre bas les armes,

Et son coeur, ravagé par la flamme, a toujours,

Pour qui s’en montre digne, un réservoir de larmes.

Charles Baudelaire

(1821-1867)

Sisina

(poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Baudelaire, Baudelaire, Charles

L’ange de poésie

et la jeune femme

L’ANGE DE POÉSIE.

Éveille-toi, ma sœur, je passe près de toi !

De mon sceptre divin tu vas subir la loi ;

Sur toi, du feu sacré tombent les étincelles,

Je caresse ton front de l’azur de mes ailes.

À tes doigts incertains, j’offre ma lyre d’or,

Que ton âme s’éveille et prenne son essor !…

Le printemps n’a qu’un jour, tout passe ou tout s’altère ;

Hâte-toi de cueillir les roses de la terre,

Et chantant les parfums dont s’enivrent tes sens,

Offre tes vers au ciel comme on offre l’encens !

Chante, ma jeune sœur, chante ta belle aurore,

Et révèle ton nom au monde qui l’ignore.

LA JEUNE FEMME.

Grâce !.. éloigne de moi ton souffle inspirateur !

Ne presse pas ainsi ta lyre sur mon cœur !

Dans mon humble foyer, laisse-moi le silence ;

La femme qui rougit a besoin d’ignorance.

Le laurier du poète exige trop d’effort…

J’aime le voile épais dont s’obscurcit mon sort.

Mes jours doivent glisser sur l’océan du monde,

Sans que leur cours léger laisse un sillon sur l’onde ;

Ma voix ne doit chanter que dans le sein des bois,

Sans que l’écho répète un seul son de ma voix.

L’ANGE DE POÉSIE.

Je t’appelle, ma sœur, la résistance est vaine.

Des fleurs de ma couronne, avec art je t’enchaîne :

Tu te débats en vain sous leurs flexibles nœuds.

D’un souffle dévorant j’agite tes cheveux,

Je caresse ton front de ma brûlante haleine !

Mon cœur bat sur ton cœur, ma main saisit la tienne ;

Je t’ouvre le saint temple où chantent les élus…

Le pacte est consommé, je ne te quitte plus !

Dans les vallons lointains suivant ta rêverie,

Je prêterai ma voix aux fleurs de la prairie ;

Elles murmureront : « Chante, chante la fleur

Qui ne vit qu’un seul jour pour vivre sans douleur. »

Tu m’entendras encor dans la brise incertaine

Qui dirige la barque en sa course lointaine ;

Son souffle redira : « Chante le ciel serein ;

Qu’il garde son azur, le salut du marin ! »

J’animerai l’oiseau caché sous le feuillage,

Et le flot écumant qui se brise au rivage ;

L’encens remplira l’air que tu respireras…

Et soumise à mes lois, ma sœur, tu chanteras !

LA JEUNE FEMME.

J’écouterai ta voix, ta divine harmonie,

Et tes rêves d’amour, de gloire et de génie ;

Mon âme frémira comme à l’aspect des cieux…

Des larmes de bonheur brilleront dans mes yeux.

Mais de ce saint délire, ignoré de la terre,

Laisse-moi dans mon cœur conserver le mystère ;

Sous tes longs voiles blancs, cache mon jeune front ;

C’est à toi seul, ami, que mon âme répond !

Et si, dans mon transport, m’échappe une parole,

Ne la redis qu’au Dieu qui comprend et console.

Le talent se soumet au monde, à ses décrets,

Mais un cœur attristé lui cache ses secrets ;

Qu’aurait-il à donner à la foule légère,

Qui veut qu’avec esprit on souffre pour lui plaire ?

Ma faible lyre a peur de l’éclat et du bruit,

Et comme Philomèle, elle chante la nuit.

Adieu donc ! laisse-moi ma douce rêverie,

Reprends ton vol léger vers ta belle patrie !

L’ange reste près d’elle, il sourit à ses pleurs,

Et resserre les nœuds de ses chaînes de fleurs ;

Arrachant une plume à son aile azurée,

Il la met dans la main qui s’était retirée.

En vain elle résiste, il triomphe… il sourit…

Laissant couler ses pleurs, la jeune femme écrit.

Sophie d’Arbouville

(1810-1850)

Le chant du cygne

Poésies et nouvelles (1840)

• fleursdumal.nl

More in: Arbouville, Sophie d', Archive A-B, Archive A-B

Op rust

Stappend uit de plattegrond ziet hij

de ruige snede van het leven pas

op de plaats van stilstand inzicht

zich ontvouwt. Zie hem aankuieren,

als een man die na lang geoefend te

hebben eindelijk aan het werk mag.

Hij vraagt zich af: is ‘Niets blijft’

hetzelfde als ‘Alles gaat weg’?

Bert Bevers

Eerder verschenen in Sterrengruis, Reinart Edities, Oss, 2000. Bert Bevers is dichter en schrijver en woont en werkt in Antwerpen (Be).

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Tristesses de la lune

Ce soir, la lune rêve avec plus de paresse;

Ainsi qu’une beauté, sur de nombreux coussins,

Qui d’une main distraite et légère caresse

Avant de s’endormir le contour de ses seins,

Sur le dos satiné des molles avalanches,

Mourante, elle se livre aux longues pâmoisons,

Et promène ses yeux sur les visions blanches

Qui montent dans l’azur comme des floraisons.

Quand parfois sur ce globe, en sa langueur oisive,

Elle laisse filer une larme furtive,

Un poète pieux, ennemi du sommeil,

Dans le creux de sa main prend cette larme pâle,

Aux reflets irisés comme un fragment d’opale,

Et la met dans son coeur loin des yeux du soleil.

Charles Baudelaire

(1821-1867)

Tristesses de la lune

(poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Baudelaire, Baudelaire, Charles

Matrijs voor herinneringen

Vermomder dan de dood is het zwijgen

achter vergelende vitrage. Van iedereen

die denkt van iemand iets te weten. Toch,

de eieren zijn bereids geraapt, beweegt

verleden wanneer het maar wil. Toen

mijn vader jong en klein was zwom hij

in de zee, wist hij niet dat ik dit schrijven

zou. Dat bedriegers gewoon zouden blijven

verzinnen. Konijnen zonder oren, meisjes

met kapotte poppen, dichters die geen

woorden kennen. Wel: water heeft geen

naam, en vluchtend wild zorgt voor later.

Bert Bevers

Eerder verschenen in Eigen terrein, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 2013. Bert Bevers is dichter en schrijver en woont en werkt in Antwerpen (Be).

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

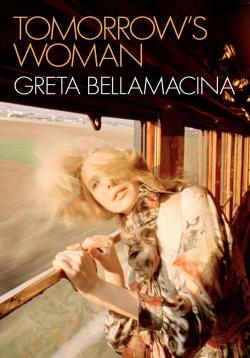

In Tomorrow’s Woman, Greta Bellamacina‘s bold, exploratory voice combines the vivid imagery of French surrealism and British romantic poetry with a modern, first-person examination of love, gender identity, motherhood, and social issues.

In Tomorrow’s Woman, Greta Bellamacina‘s bold, exploratory voice combines the vivid imagery of French surrealism and British romantic poetry with a modern, first-person examination of love, gender identity, motherhood, and social issues.

Andy Warhol’s Interview Magazine writes that “Bellamacina is garnering critical acclaim for her way with words and her ability to translate the classic poetic form into the contemporary creative landscape.”

Greta Bellamacina is an actress, filmmaker, and poet. She was born in London and made her acting debut in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire at the age of thirteen. She trained at RADA, where she performed a variety of lead theatre roles, before going on get a B.A. in English at King’s College London. Her feature film Hurt by Paradise is currently in post-production.

As a poet, Greta Bellamacina was shortlisted as Young Poet Laureate in 2014 for her debut collection, Kaleidoscope. In 2015, she edited On Love, a survey of contemporary British love poetry from Ted Hughes to the present. The same year, she published Perishing Tame, her first collection with New River Press, “a dazzling meditation on motherhood, female identity, ennui and love,” which she launched at The Shakespeare & Company in Paris.

In 2016, she published a collection of collaborative poetry with Robert Montgomery: Points for Time in the Sky, a pyschogeographical journey through modern Britain, and a rare example of collaborative poetry in British literature. The same year, she edited Smear, an anthology of contemporary feminist poetry. Dazed said the collection “unapologetically confronts self-image, body autonomy and our relationships with each other, celebrating the imperfect, frank woman.” In 2018, she was commissioned by the National Poetry Library to write a group of poems for their Odyssey series—modern mediations on Homer’s Odyssey.

Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine says Greta “is garnering critical acclaim for her way with words and her ability to translate the classic poetic form into the contemporary creative landscape.”

This is her first volume of her poetry to be released in the United States.

Greta Bellamacina

Tomorrow’s Woman

Paperback

112 pages

6 Feb. 2020

ISBN-13 : 978-1524854096

ISBN-10 : 1524854093

Publisher : Andrews McMeel Publishing

Product Dimensions : 14.22 x 0.76 x 20.83 cm

Reading level : 15 and up

Language: : English

£7.72

# more poetry

Greta Bellamacina

Tomorrow’s Woman

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Bellamacina, Greta

The Little Vagabond

Dear mother, dear mother, the Church is cold;

But the Alehouse is healthy, and pleasant, and warm.

Besides, I can tell where I am used well;

The poor parsons with wind like a blown bladder swell.

But, if at the Church they would give us some ale,

And a pleasant fire our souls to regale,

We’d sing and we’d pray all the livelong day,

Nor ever once wish from the Church to stray.

Then the Parson might preach, and drink, and sing,

And we’d be as happy as birds in the spring;

And modest Dame Lurch, who is always at church,

Would not have bandy children, nor fasting, nor birch.

And God, like a father, rejoicing to see

His children as pleasant and happy as he,

Would have no more quarrel with the Devil or the barrel,

But kiss him, and give him both drink and apparel.

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

The Little Vagabond

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Beauty abounds in Jericho Brown’s Pulitzer Prize-winning poetry collection, despite and inside of the evil that pollutes the everyday.

A National Book Award finalist, The Tradition questions why and how we’ve become accustomed to terror: in the bedroom, the classroom, the workplace, and the movie theater. From mass shootings to rape to the murder of unarmed people by police, Brown interrupts complacency by locating each emergency in the garden of the body, where living things grow and wither—or survive.

A National Book Award finalist, The Tradition questions why and how we’ve become accustomed to terror: in the bedroom, the classroom, the workplace, and the movie theater. From mass shootings to rape to the murder of unarmed people by police, Brown interrupts complacency by locating each emergency in the garden of the body, where living things grow and wither—or survive.

In the urgency born of real danger, Brown’s work is at its most innovative. His invention of the duplex—a combination of the sonnet, the ghazal, and the blues—is an all-out exhibition of formal skill, and his lyrics move through elegy and memory with a breathless cadence. Jericho Brown is a poet of eros: here he wields this power as never before, touching the very heart of our cultural crisis.

Jericho Brown is a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard, and the National Endowment for the Arts, and he is the winner of a Whiting Award. Brown’s first book, Please (New Issues, 2008), won the American Book Award. His second book, The New Testament (Copper Canyon, 2014), won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. His third collection is The Tradition (Copper Canyon, 2019)—winner of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry and a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award. His poems have appeared in Bennington Review, BuzzFeed, Fence, jubilat, The New Republic, The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, TIME, and several volumes of The Best American Poetry. He is an associate professor and the director of the Creative Writing Program at Emory University.

The Tradition

poems by Jericho Brown

(Winner of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry)

Format: Paperback

Paperback

110 pages

ISBN-10 : 1556594860

ISBN-13 : 978-1556594861

Publisher : Copper Canyon Press

2 April 2019

Product Dimensions : 22.35 x 14.99 x 1.27 cm

Language: English

$17.00 list price

Jericho Brown

Awards and Honors

Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, 2020

Whiting Writers Award

American Book Award

National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship

Radcliffe Institute at Harvard University Fellowship

Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference Fellowship

Krakow Poetry Seminar Fellowship

John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship

Lambda Literary Trustee Award, 2020

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Awards & Prizes

Les Yeux de Berthe

Vous pouvez mépriser les yeux les plus célèbres,

Beaux yeux de mon enfant, par où filtre et s’enfuit

Je ne sais quoi de bon, de doux comme la Nuit!

Beaux yeux, versez sur moi vos charmantes ténèbres!

Grands yeux de mon enfant, arcanes adorés,

Vous ressemblez beaucoup à ces grottes magiques

Où, derrière l’amas des ombres léthargiques,

Scintillent vaguement des trésors ignorés!

Mon enfant a des yeux obscurs, profonds et vastes,

Comme toi, Nuit immense, éclairés comme toi!

Leurs feux sont ces pensers d’Amour, mêlés de Foi,

Qui pétillent au fond, voluptueux ou chastes.

Charles Baudelaire

(1821-1867)

Les Yeux de Berthe

(poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Baudelaire, Baudelaire, Charles

Vergeelde brieven met een lintje erom

In verkleurde inkt de verdwenen stemmen

van broeders die nooit paters zouden worden.

Over geplooide superplies in zwijgende kasten,

en opwolkende wierook. De zinnen ademen

schuchter voor de sluier van hun namen, als

fluisteringen uit het hart. Ze dansten ooit

de horlepijp, maar de melodie daarvan zonk

traag weg uit hun oren als een steen in veen.

Bert Bevers

Eerder verschenen op Versindaba, Stellenbosch, februari 2014

Bert Bevers is a poet and writer who lives and works in Antwerp (Be)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

The Grey Monk

“I die, I die!” the Mother said,

“My children die for lack of bread.

What more has the merciless Tyrant said?”

The Monk sat down on the stony bed.

The blood red ran from the Grey Monk’s side,

His hands and feet were wounded wide,

His body bent, his arms and knees

Like to the roots of ancient trees.

His eye was dry; no tear could flow:

A hollow groan first spoke his woe.

He trembled and shudder’d upon the bed;

At length with a feeble cry he said:

“When God commanded this hand to write

In the studious hours of deep midnight,

He told me the writing I wrote should prove

The bane of all that on Earth I lov’d.

My Brother starv’d between two walls,

His Children’s cry my soul appalls;

I mock’d at the rack and griding chain,

My bent body mocks their torturing pain.

Thy father drew his sword in the North,

With his thousands strong he marched forth;

Thy Brother has arm’d himself in steel

To avenge the wrongs thy Children feel.

But vain the Sword and vain the Bow,

They never can work War’s overthrow.

The Hermit’s prayer and the Widow’s tear

Alone can free the World from fear.

For a Tear is an intellectual thing,

And a Sigh is the sword of an Angel King,

And the bitter groan of the Martyr’s woe

Is an arrow from the Almighty’s bow.

The hand of Vengeance found the bed

To which the Purple Tyrant fled;

The iron hand crush’d the Tyrant’s head

And became a Tyrant in his stead.”

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

The Grey Monk

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature