Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

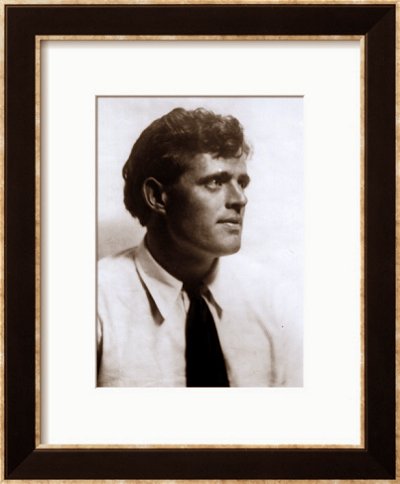

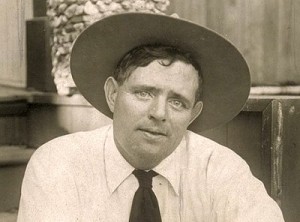

Vachel Lindsay

(1879 – 1931)

Buddha

Would that by Hindu magic we became

Dark monks of jeweled India long ago,

Sitting at Prince Siddartha’s feet to know

The foolishness of gold and love and station,

The gospel of the Great Renunciation,

The ragged cloak, the staff, the rain and sun,

The beggar’s life, with far Nirvana gleaming:

Lord, make us Buddhas, dreaming.

Vachel Lindsay poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Archive K-L, CLASSIC POETRY, Lindsay, Vachel

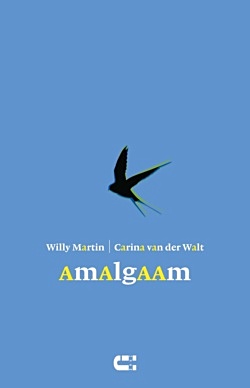

Amalgaam is een duobundel van twee dichters, Willy Martin en Carina van der Walt. Martin was in een vorig leven een avontuurlijke hoogleraar lexicologie die zich vooral richtte op nieuwe technologie en systematiek om taal te kunnen voorzien van het juiste frame. Van der Walt begon in het reguliere onderwijs als docente Afrikaans, Nederlands en Setswana en legde zich later toe op het academisch onderzoek naar kinder- en jeugdliteratuur. In het grootste deel van de bundel worden Zuid-Afrikaans en Nederlands afgewisseld, waarbij ieder zijn eigen moedertaal voor zijn rekening neemt: Martin het Nederlands (en Vlaams), Van der Walt het Afrikaans.

De bundel heet Amalgaam, en dat woord wordt – zoals het een uitgave van een lexicograaf betaamt – netjes in een voetnoot toegelicht. In de figuurlijke zin betekent ‘amalgaam’ in zowel het Afrikaans als in het Nederlands hetzelfde: een mengsel, mengelmoes. Die beschrijving is behoorlijk van toepassing op dit gezamenlijke werk: het gaat om twee verschillende dichters uit verschillende generaties die niet alleen duidelijk hun eigen thematiek en stijl hebben, maar die ook nog eens in een aparte taal schrijven. Het probleem daarbij is wel dat die talen ‘valse vrienden’ zijn – ze hebben een gezamenlijk verleden, maar de schijnbare overlap bestaat voor een deel uit goed afgedekte valkuilen. Al in het voorwoord wordt de wordingsgeschiedenis vanuit het Groot Woordenboek Afrikaans en Nederlands (de culminatie van Martin’s werk als hoogleraar) uit de doeken gedaan, en daarmee is al meteen duidelijk dat de lezer het nodige te wachten staat.

De normale lezer moge het op dit moment misschien duizelen, maar het valt wel mee. Amalgaam is een eerste voorzichtig experiment, en blijft volledig in het nette. Het is geen verraderlijke of dubbelzinnige smeltkroes geworden van talen en dichters, die de lezer de hele tijd op het verkeerde been zet – dat hebben de dichters overgelaten voor een volgend deel. De bundel is in zijn huidige vorm een gedegen bloemlezing waarin gedichten op elkaar gestapeld zijn die samen een mooi beeld geven van twee nogal verschillende dichters. Twee voor de prijs van een, zogezegd. Beiden hebben een prettige stijl die de ander niet in de weg zit. Martin is wat serieuzer en plechtstatiger, en Van der Walt wat levendiger en politieker – bijvoorbeeld over de betekenis van Lampedusa voor het zelfbeeld van Europa. Met name de gedichten van Van der Walt geven de indruk dat ze geschreven zijn voor een bezielende voordracht.

De bundel bevat naast oorspronkelijke gedichten ook een aantal vertalingen van gedichten van anderen, van uiteenlopende dichters zoals Paul van Ostaijen, Adam Small, Tsjebbe Hettinga, Hans du Plessis en Peter Snyders. Die buitenboordmotor had de bundel niet nodig: met name in hun eigen woorden is het eigen geluid al duidelijk genoeg te horen.

Vraag is natuurlijk hoe het vervolg van dit experiment eruit zal zien. Het is duidelijk dat er nog veel meer potentiële poëtische energie zit in het grensgebied tussen de twee zustertalen en tussen andere verwante talen. Door hun unieke professionele en persoonlijke achtergrond zijn Van der Walt en Martin ideale mentale experimentele opstellingen om als woordjesversneller tussen deze talen te fungeren. Het samenwerkingsproces zal om de energiedichtheid omhoog te krijgen waarschijnlijk nog intensiever moeten zijn. Door de dichters niet enkel per heel gedicht om en om te laten werken in of de ene taal of de andere, maar per regel aan zet te laten – of zelfs nog vaker, desnoods per woord of zelfs lettergreep, en in een taal naar keuze – kunnen de talen tegen elkaar in gaan draaien en met zeer hoge snelheid tegen elkaar aanbotsen. Het gedroomde resultaat is dan niet meer te duiden als het een of het ander, maar zou in het ideale geval leiden tot een spannende fusie van kernen uit beide talen en culturen. Dat is misschien minder toegankelijk dan Amalgaam – hoe intensiever de opeenstapeling van frames uit beide talen, hoe dieper de benodigde kennis – maar zelfs als dat benodigde dubbele taalgevoel maar voor een zeer klein deel van de mensheid zal zijn weggelegd, is er voor de rest vast al veel plezier te beleven door het spectaculaire uiteenspatten van elementaire talige deeltjes. Amalgaam is de eerste speelse stap op een veelbelovende pad, en hopelijk zetten Van der Walt en Martin aangemoedigd door het succes van hun geslaagde dubbelbundel door met dit experiment – alleen of met hulp van anderen.

Michiel Leenaars

____________________________________

Willy Martin & Carina van der Walt

Amalgaam

Prijs € 15,-

95 pag.

ISBN 978 90 8684 117 2

Uitgeverij IJzer

Postbus 628

3500 AP Utrecht

Tel: 030 – 2521798

http://www.uitgeverij-ijzer.nl/

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Carina van der Walt, Walt, Carina van der, Willy Martin

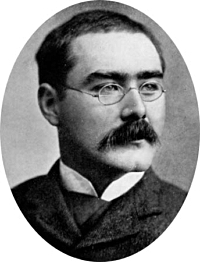

Rudyard Kipling

(1865-1936)

The Vampire

A fool there was and he made his prayer

(Even as you and I!)

To a rag and a bone and a hunk of hair

(We called her the woman who did not care)

But the fool he called her his lady fair

(Even as you and I!)

Oh, the years we waste and the tears we waste

And the work of our head and hand

Belong to a woman who did not know

(And now we know that she never could know)

And did not understand!

A fool there was and his goods he spent

(Even as you and I!)

Honour and faith and a sure intent

(And it wasn’t the least what the lady meant)

But a fool must follow his natural bent

(Even as you and I!)

Oh the toil we lost and the spoil we lost

And the excellent things we planned

Belong to the woman who didn’t know why

(And now we know that she never knew why)

And did not understand!

The fool was stripped to his foolish hide

(Even as you and I!)

Which she might have seen as she threw him aside

(But it isn’t on record the lady tried)

So some of him lived but the most of him died

(Even as you and I!)

And it isn’t the shame and it isn’t the blame

That stings like a white hot brand

It’s coming to know that she never knew why

(Seeing, at last, she could never knew why)

And never could understand!

Rudyard Kipling poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Archive K-L, CLASSIC POETRY, Kipling, Rudyard

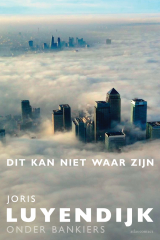

Joris Luyendijk (1971) is te gast in VPRO BOEKEN over zijn nieuwste boek ‘Dit kan niet waar zijn’. Twee jaar geleden ging Luyendijk met zijn gezin in Londen wonen. Hij ging werken voor The Guardian, die hem de opdracht gaf om vanuit antropologisch perspectief te schrijven over The City, het financiële hart van Groot-Brittannië. De conclusie van het boek is even stevig als pijnlijk: de instellingen die ervoor moeten zorgen dat de economie functioneert, kunnen de wereld in de afgrond doen storten.

Joris Luyendijk (1971) is te gast in VPRO BOEKEN over zijn nieuwste boek ‘Dit kan niet waar zijn’. Twee jaar geleden ging Luyendijk met zijn gezin in Londen wonen. Hij ging werken voor The Guardian, die hem de opdracht gaf om vanuit antropologisch perspectief te schrijven over The City, het financiële hart van Groot-Brittannië. De conclusie van het boek is even stevig als pijnlijk: de instellingen die ervoor moeten zorgen dat de economie functioneert, kunnen de wereld in de afgrond doen storten.

Joris Luyendijk

VPRO Boeken

zondag 22 februari 2015

NPO 1, 11.20 uur

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, FDM in London, MONTAIGNE

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

(1729-1781)

Das Mädchen

Zum Mädchen wünscht’ ich mir – und wollt’ es, ha! recht lieben –

Ein junges, nettes, tolles Ding,

Leicht zu erfreun, schwer zu betrüben,

Am Wuchse schlank, im Gange flink,

Von Aug’ ein Falk,

Von Mien’ ein Schalk;

Das fleißig, fleißig liest:

Weil alles, was es liest,

Sein einzig Buch – der Spiegel ist;

Das immer gaukelt, immer spricht,

Und spricht und spricht von tausend Sachen,

Versteht es gleich das Zehnte nicht

Von allen diesen tausend Sachen:

Genug, es spricht mit Lachen,

Und kann sehr reizend lachen.

Solch Mädchen wünscht’ ich mir! – Du, Freund, magst deine Zeit

Nur immerhin bei schöner Sittsamkeit,

Nicht ohne seraphin’sche Tränen,

Bei Tugend und Verstand vergähnen.

Solch einen Engel

Ohn’ alle Mängel

Zum Mädchen haben:

Das hieß’ ein Mädchen haben? –

Heißt eingesegnet sein, und Weib und Hausstand haben.

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, CLASSIC POETRY

Amy Lowell

(1874–1925)

To a Friend

I ask but one thing of you, only one,

That always you will be my dream of you;

That never shall I wake to find untrue

All this I have believed and rested on,

Forever vanished, like a vision gone

Out into the night. Alas, how few

There are who strike in us a chord we knew

Existed, but so seldom heard its tone

We tremble at the half-forgotten sound.

The world is full of rude awakenings

And heaven-born castles shattered to the ground,

Yet still our human longing vainly clings

To a belief in beauty through all wrongs.

O stay your hand, and leave my heart its songs!

Amy Lowell poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Archive K-L, CLASSIC POETRY, Lowell, Amy

![]()

Babelmatrix Translation Project

Imre Kertész

Imre Kertész was born in Budapest on November 9, 1929. Of Jewish descent, in 1944 he was deported to Auschwitz and from there to Buchenwald, where he was liberated in 1945. On his return to Hungary he worked for a Budapest newspaper, Világosság, but was dismissed in 1951 when it adopted the Communist party line. After two years of military service he began supporting himself as an independent writer and translator of German-language authors such as Nietzsche, Hofmannsthal, Schnitzler, Freud, Roth, Wittgenstein, and Canetti, who have all had a significant influence on his own writing.

Kertész’s first novel, Sorstalanság (Eng. Fateless, 1992; see WLT 67:4, p. 863), a work based on his experiences in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, was published in 1975. “When I am thinking about a new novel, I always think of Auschwitz,” he has said. This does not mean, however, that Sorstalanság is autobiographical in any simple sense: Kertész says himself that he has used the form of the autobiographical novel but that it is not autobiography. Sorstalanság was initially rejected for publication. When published eventually in 1975, it was received with compact silence. Kertész has written about this experience in A kudarc (1988; Fiasco). This novel is normally regarded as the second volume in a trilogy that begins with Sorstalanság and concludes with Kaddis a meg nem született gyermekért (1990; Eng. Kaddish for a Child Not Born, 1997; see WLT 74:1, p. 205), in a title that refers to the Jewish prayer for the dead. In Kaddis a meg nem született gyermekért, the protagonist of Sorstalanság and A kudarc, György Köves, reappears. His Kaddish is said for the child he refuses to beget in a world that permitted the existence of Auschwitz. Other prose works are A nyomkereso” (1977; The pathfinder) and Az angol labogó (1991; The English flag; see WLT 67:2, p. 412)

Gályanapló (Részletek) (Hungarian)

Ahhoz, hogy valaki – dehogy az „emberiség!” – csupán a saját élete megváltója, föloldozója lehessen, egy teljes, hihetetlenül intenzív és állandó belsö munkával eltöltött élet szükséges. Az embernek van egy förtelmes élete – a történelem-, és van egy nála sokkal bölcsebb, hatalmas világmeséje, amelyben istenséggé, mágussá válik; és ez a mese éppoly csoda, mint amilyen hihetetlen a történelmi, a „reális” élete.

Augusztus 11. Minden véget ért, és minden újrakezdödött; de máshol kezdödött, és talán máshová visz. Tegnapelött éjszaka az erkélyen, hüvösödo” szélfutamok, a Pasaréti úti fák nagy, felhöforma, sötét lombozata, alatta az aranyló világítás – egy pillanatig mintha nem is ez a jól ismert lidércváros lenne. Mély, mély melankólia, emlékek, mintha az elmúlás környékezne, csupa közhely, csupa valóság, csupa unalmas igazság, akár a halál.

L., az író, aki viszonylagosnak fogja fel az irodalmat. Szemben Schönberg nézetével, miszerint a mu”vészethez elég az igazság, L. szerint a müvészetnek a túlélést kell szolgálnia: hiszen, mondja, ha meglátjuk a puszta igazságot, akkor nem marad hátra más, mint hogy felkössük magunkat – vagy netalán azt, aki az igazságot nekünk megmutatta. Nem éppen szokatlan magatartás; nem csodálkoznék, ha L.-ról kiderülne, hogy családapa, s csupán a gyermekei jövo”jéért teszi, amit tennie kell. Csakhogy a viszonylagos irodalom mindig rossz irodalom, és a nem radikális müvészet mindig középszeru” müvészet: jó müvésznek nincs más esélye, mint hogy igazat mondjon, és az igazat radikálisan mondja. Etto”l még életben lehet maradni, hiszen a hazugság nem az egyetlen és kizárólagos föltétele az életnek, ha sokan nem is látnak egyéb lehetöséget.

Mostanában gyakran elképzelek valakit, homályos alak, egy emberi lény, kortalan, persze inkább ido”s vagy legalábbis idösödo” férfi. Jön-megy, végzi a dolgát, éli az életét, szenved, szeret, elutazik, hazatér, olykor beteg, máskor úszni, társaságba, kártyázni jár; mindeközben azonban, amint akad egy szabad perce, tüstént benyit egy eldugott fülkébe, gyorsan – és mintegy szórakozottan – leül valami ócska hangszer elé, leüt néhány akkordot, majd félhalkan improvizálni kezd, évtizedeken keresztül játssza ugyanegy téma immár számtalanadik variációját. Nemsoká felugrik, mennie kell – de amint újabb szabadideje adódik, ismét ott látjuk öt a hangszernél, mintha az élete csak amolyan két játék közötti, kényszer közbevetés lenne. Ha ezek a hangok, amiket a hangszerböl kicsal, mondjuk, megállnának, és egymásba su”ru”södve mintegy megfagynának a levego”ben, talán valami görcsös kataton mozdulatra emlékeztetö jégkristályképzödményt látnánk, amelyben, jobban is megnézve, kétségkívül felismerheto” lenne valamilyen kifejezö szándé makacssága, ha csupán a monotóniáé is; ha meg netán lekottáznák, végül alighanem ki lehetne venni egy mindegyre sürüödo” fúga bontakozó körvonalait, mely mind határozottabban tör célja felé, csakhogy e célt mind távolabbra tolja, taszigálja magától, s így mégis mind bizonytalanabbá válik. – Kinek játszik? Miért játszik? Maga sem tudja. Söt – és azért mégiscsak ez a legfurcsább – nem is hallja, hogy mit játszik. Mintha a kísérteties erö, amely újra meg újra odaparancsolja a hangszerhez, megfosztotta volna a hallásától, hogy egyedül neki játsszon. -De ó legalább hallja-e? (A kérdés azonban, lássuk be, értelmetlen: a játékost természetesen boldognak kell elképzelnünk.)

1992

Galeerentagebuch (Auszüge) (German)

Um Erlöser – keineswegs der »Menschheit«! – lediglich seines eigenen Lebens sein zu können, um sich für das eigene Leben Absolution erteilen zu können, ist ein volles, unsagbar intensives und von ständiger innerer Arbeit erfülltes Leben notwendig. Der Mensch hat ein grauenhaftes Leben – die Geschichte –, und er hat die Erzählung von der Welt, mächtig und viel weiser als er, in der er zur Gottheit, zum Magier wird; und diese Erzählung ist genauso ein Wunder, wie sein geschichtliches, «reales» Leben etwas Unglaubliches ist.

11. August Alles hat ein Ende, und alles begann von vorn; doch es begann anderswo und führt vielleicht anderswohin. Vorgestern nacht auf dem Balkon, ein kühler Wind, das große, wolkenförmige, dunkle Laubdach der Bäume in der Pasareti-Straße, darunter die schummrige Beleuchtung – für einen Moment war mir, als sei es nicht die vertraute Alptraumstadt. Tiefe, tiefe Melancholie, Erinnerungen, als umgebe mich dei Vergänglichkeit, voll Banalität, voll Wirklichkeit, voll langweiliger Wahrheit, wie der Tod.

L., der Schriftsteller, der die Literatur relativ auffaßt. Im Gegensatz zu Schönberg, nach dessen Ansicht Wahrheit für die Kunst genügt, muß die Kunst L. zufolge dem Überleben dienen, denn, sagt er, wenn wir die nackte Wahrheit erblicken, bleibt uns nichts anderes übrig, als uns aufzuhängen – oder vielleicht den, der uns die Wahrheit gezeigt hat. Keine ganz ungewöhnliche Haltung; es würde mich nicht wundern, wenn sich herausstellte, daß L. Familienvater ist und das, was er tut, nur für die Zukunft seiner Kinder tut. Nur daß relative Literatur immer schlechte Literatur und nichtradikale Kunst immer mittelmäßige Kunst ist: Der wirkliche Künstler hat keine andere Chance, als die Wahrheit zu sagen und die Wahrheit radikal zu sagen. Deswegen kann er trotzdem am Leben bleiben, denn die Lüge ist nicht einzige und ausschließliche Bedingung des Lebens, selbst wenn viele keine sonstigen Möglichkeiten sehen.

In letzter Zeit stelle ich mir häufig etwas vor, eine unklare Gestalt, ein menschliche; Wesen, einen alterslosen, freilich eher alten oder doch älteren Mann. Er kommt und geht, erledigt seine Dinge, lebt sein Leben, leidet, liebt, verreist, kehrt heim, manchmal ist er krank, manchmal geht er schwimmen, zu Bekannten oder Karten spielen; zwischendurch jedoch, sobald sich eine freie Minute findet, öffnet er die Tür einer versteckten Zelle, stetzt sich rasch – und gleichsam zerstreut – vor ein schäbiges Instrument, schlägt einige Akkorde an und beginnt dann halblaut zu improvisieren, eine weitere von inzwischen zahllosen Variationen des seit Jahrzehnten gespielten, immer gleichen Themas. Kurz darauf springt er auf, muß gehendoch sobald sich wieder freie Zeit findet, sehen wir ihn abermals vor dem Instrument, als sei sein Leben nur die notgedrungene Unterbrechung zwischen zwei Spielen. Würden die Töne, die er dem Instrument entlockt, aufstehen und, gleichsam ineinander verdichtet, in der Luft gefrieren, würden wir vielleicht ein Eiskristallgebilde erblicken, an eine verkrampfte katatonische Bewegung erinnernd, worin, bei genauerer Betrachtung, zweifellos die Hartnäckigkeit einer Ausdrucksabsicht zu erkennen wäre, wenn auch nur die der Monotonie; setzten wir sie gar in Noten, könnten wir vermutlich die Umrisse einer sich mehr und mehr verdichtenden Fuge herauslösen, die immer entschlossener zu ihrem Ziel durchbricht, dabei aber dieses Ziel immer weiter fortschiebt, fortstößt von sich, und so wird es dennoch immer ungewisser. – Für wen spielt er? Warum spielt er? Er weiß es selbst nicht. Zudem – und das ist das Merkwürdigste daran – kann er nicht einmal hören, was er spielt. Als habe ihm die gespenstische Kraft, die ihn wieder und wieder an sein Instrument zwingt, das Gehör geraubt, damit er allein für sie spiele. – Ob jedoch sie ihn wenigstens hört? (Die Frage, sehen wir es ein, ist sinnlos, aber den Spieler müssen wir uns natürlich glücklich vorstellen.)

Schwamm, Kristin

![]()

FLEURSDUMAL.NL MAGAZINE

More in: Archive K-L, Kertész, Imre

![]()

Babelmatrix Translation Project

Imre Kertész

Imre Kertész was born in Budapest on November 9, 1929. Of Jewish descent, in 1944 he was deported to Auschwitz and from there to Buchenwald, where he was liberated in 1945. On his return to Hungary he worked for a Budapest newspaper, Világosság, but was dismissed in 1951 when it adopted the Communist party line. After two years of military service he began supporting himself as an independent writer and translator of German-language authors such as Nietzsche, Hofmannsthal, Schnitzler, Freud, Roth, Wittgenstein, and Canetti, who have all had a significant influence on his own writing.

Kertész’s first novel, Sorstalanság (Eng. Fateless, 1992; see WLT 67:4, p. 863), a work based on his experiences in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, was published in 1975. “When I am thinking about a new novel, I always think of Auschwitz,” he has said. This does not mean, however, that Sorstalanság is autobiographical in any simple sense: Kertész says himself that he has used the form of the autobiographical novel but that it is not autobiography. Sorstalanság was initially rejected for publication. When published eventually in 1975, it was received with compact silence. Kertész has written about this experience in A kudarc (1988; Fiasco). This novel is normally regarded as the second volume in a trilogy that begins with Sorstalanság and concludes with Kaddis a meg nem született gyermekért (1990; Eng. Kaddish for a Child Not Born, 1997; see WLT 74:1, p. 205), in a title that refers to the Jewish prayer for the dead. In Kaddis a meg nem született gyermekért, the protagonist of Sorstalanság and A kudarc, György Köves, reappears. His Kaddish is said for the child he refuses to beget in a world that permitted the existence of Auschwitz. Other prose works are A nyomkereso” (1977; The pathfinder) and Az angol labogó (1991; The English flag; see WLT 67:2, p. 412)

Sorstalanság (Hungarian)

A pályaudvarhoz érve, mivel kezdtem igen érezni a lábom, no meg mivel a sok többi közt a régröl ismert számmal is épp elibém kanyarodott egy, villamosra szálltam. Szikár öregasszony húzódott a nyitott peronon egy kissé félrébb, fura, ódivatú csipkegallérban. Hamarosan egy ember jött, sapkában, egyenruhában, és a jegyemet kérte. Mondtam néki: nincsen. Indítványozta: váltsak. Mondtam: idegenböl jövök, nincsen pénzem. Akkor megnézte a kabátomat, engem, s azután meg az öregasszonyt is, majd értésemre adta, hogy az utazásnak törvényei vannak, s ezeket a törvényeket nem ö, hanem az o” fölötte állók hozták. – Ha nem vált jegyet, le kell szállnia – volt a véleménye. Mondtam neki: de hisz fáj a lábam, s erre, észrevettem, az öregasszony ki, a tájék felé fordult, de oly sértödötten valahogyan, mintha csak néki hánytam volna a szemére netán, nem tudnám, mért. De a kocsi nyitott ajtaján, már messziroö nagy lármával, termetes, fekete, csapzott ember csörtetett ki. Nyitott inget, világos vászonöltönyt, a válláról szíjon függö fekete dobozt, kezében meg irattáskát hordott. Miféle dolog ez, kiáltotta, és: – Adjon egy jegyet! – intézkedett, pénzdarabot nyújtva, lökve inkább a kalauznak oda. Próbáltam köszönetet mondani, de félbeszakított, indulatosan tekintve körbe: – Inkább némelyeknek szégyenkezniük kellene – szólt, de a kalauz már a kocsiban járt, az öregasszony meg továbbra is kinézett. Akkor, megenyhült arccal, énfelém fordult. Kérdezte: – Németországból jössz, fiam? – Igen. – Koncentrációs táborból-e? – Természetesen. – Melyikbo”l? – A buchenwaldiból. – Igen, hallotta már hírét, tudja, az is „a náci pokolnak volt egyik bugyra” – így mondta. – Honnan hurcoltak ki? – Budapestro”l. – Meddig voltál oda? – Egy évig, egészében. – Sok mindent láthattál, fiacskám, sok borzalmat – mondta arra, s nem feleltem semmit. No de – így folytatta – foöhogy vége, elmúlt, s földerülö arccal a házakra mutatva, melyek közt épp csörömpöltünk, érdeklödött: mit érzek vajon most, újra itthon, s a város láttán, melyet elhagytam? Mondtam neki: – Gyülöletet. – Elhallgatott, de hamarosan azt az észrevételt tette, hogy meg kell, sajnos, értenie az érzelmeimet. Egyébként öszerinte „adott helyzetben” a gyülöletnek is megvan a maga helye, szerepe, „so haszna”, és föltételezi, tette hozzá, egyetértünk és jól tudja, hogy kit gyu”lölök. Mondtam neki: – Mindenkit. – Megint elhallgatott, ezúttal már hosszabb ido”re, utána meg újra kezdte: – Sok borzalmon kellett-e keresztülmenned? –, s azt feleltem, attól függ, mit tart borzalomnak. Bizonyára – mondta erre, némiképpen feszélyezettnek látszó arccal – sokat kellett nélkülöznöm, éheznem, és valószínu”leg vertek is talán, s mondtam neki: természetesen. – Miért mondod, édes fiam – kiáltott arra fel, de már-már úgy néztem, a türelmét vesztve –, mindenre azt, hogy „természetesen”, és mindig olyasmire, ami pedig egyáltalán nem az?! – Mondtam: koncentrációs táborban ez természetes. – Igen, igen – így o” –, ott igen, de… – s itt elakadt, habozott kissé – de… nohát, de maga a koncentrációs tábor nem természetes! – bukkant végre a megfelelo” szóra mintegy, s nem is feleltem néki semmit, mivel kezdtem lassan belátni: egy s más dologról sosem vitázhatunk, úgy látszik, idegenekkel, tudatlanokkal, bizonyos értelemben véve gyerekekkel, hogy így mondjam. Különben is – kaptam magam a változatlanul ott levo”, s éppen csak egy kissé kopárabbá és gondozatlanabbá vált térröl rajta –, ideje leszállanom, és ezt be is jelentettem neki. De velem tartott, s egy árnyas, támlája vesztett padot mutatva arrébb, indítványozta: telepednénk oda egy percre.

Elöször némelyest bizonytalankodni látszott. Valójában – jegyezte meg – most kezdenek még csak „igazán feltárulni a rémségek”, és hozzátette, „a világ egyelo”re értetlenül áll a kérdés elött: hogyan, miként is történhetett mindez egyáltalán meg”? Nem szóltam semmit, és akkor egész felém fordulva, egyszerre csak azt mondta: – Nem akarnál fiacskám, beszámolni az élményeidro”l? – Elcsodálkoztam kissé, és azt feleltem, hogy roppant sok érdekeset nemigen tudnék mondani neki. Akkor mosolygott kicsikét, és azt mondta: – Nem nekem: a világnak. – Amire, míg jobban csodálkozva, tudakoltam to”le: – De hát miröl? – A lágerek pokláról – válaszolta ö, melyre én azt jegyeztem meg, hogy meg egyáltalában semmit se mondhatok, mivel a pokolt nem ismerem, és még csak elképzelni se tudnám. De kijelentette, ez csak afféle hasonlat: – Nem pokolnak kell-e – kérdezte – elképzelnünk a koncentrációs tábort? – és azt feleltem, sarkammal közben néhány karikát írva lábam alá a porba, hogy ezt mindenki a maga módja és kedve szerint képzelheti el, hogy az én részemro”l azonban mindenesetre csak a koncentrációs tábort tudom elképzelni, mivel ezt valamennyire ismerem, a pokolt viszont nem. – De ha, mondjuk, mégis? – ero”sködött, s pár újabb karika után azt feleltem: – Akkor olyan helynek képzelném, ahol nem lehet unatkozni –; márpedig, tettem hozzá, koncentrációs táborban lehetett, meg Auschwitzban is – már bizonyos föltételek közt, persze. Arra hallgatott egy kicsit, majd meg azt kérdezte, de némiképp valahogy már-már a kedve ellenére szinte, úgy éreztem: – És ezt mivel magyarázod? –, s kis gondolkodás után azt találtam: – Az ido”vel. – Hogyhogy az ido”vel? – Úgy, hogy az ido” segít. – Segít…? miben? – Mindenben –, s próbáltam neki elmagyarázni, mennyire más dolog például megérkezni egy, ha nem is éppen fényu”zo”, de egészében elfogadható, tiszta, takaros állomásra, ahol csak lassacskán, ido”rendben, fokonként világosodik meg elo”ttünk minden. Mire egy fokozaton túl vagyunk, magunk mögött tudjuk, máris jön a következo”. Mire aztán mindent megtudunk, már meg is értettünk mindent. S mialatt mindent megért, ezenközben nem marad tétlen az ember: máris végzi az új dolgát, él, cselekszik, mozog, teljesíti minden újabb fok minden újabb követelményét. Ha viszont nem volna ez az ido”rend, s az egész ismeret mindjárt egyszerre, ott a helyszínen zúdulna ránk, meglehet, azt el sem bírná tán se koponyánk, sem a szívünk – próbáltam valamennyire megvilágítani néki, amire ö zsebéböl közben szakadozott papirosú dobozt halászva elö, melynek gyu”rött cigarettáit énfelém is idetartotta, de elhárítottam, majd két nagy szippantás után két könyékkel a térdére támaszkodva, így elo”redöntött felso”testtel és rám se nézve, kissé valahogy érctelen, tompa hangon ezt mondta: – Értem. – Másrészt, folytattam, az ebben a hiba, mondhatnám hátrány, hogy az ido”t viszont ki is kell tölteni. Láttam például – mondtam neki – foglyokat, akik négy, hat vagy éppen tizenkét esztendeje voltak már – pontosabban: voltak még mindig meg – koncentrációs táborban. Mármost ezeknek az embereknek mindezt a négy, hat vagy tizenkét esztendo”t, vagyis utóbbi esetben tizenkétszer háromszázhatvanöt napot, azaz tizenkétszer, háromszázhatvanötször huszonnégy órát, továbbá tizenkétszer, háromszázhatvanötször, huszonnégyszer… s mindezt vissza, pillanatonként, percenként, óránként, naponként: vagyis végig az egészet el kellett valahogy tölteniök. Megint másrészt viszont – fu”ztem tovább – épp ez segíthetett o”nekik is, mert ha mindez a tizenkétszer, háromszázhatvanötször, huszonnégyszer, hatvanszor és újra hatvanszornyi ido” mind egyszerre, egyetlen csapással szakadt volna a nyakukba, úgy bizonyára ök se állták volna – mint ahogy így állani bírták – se testtel, sem aggyal. S mivel hallgatott, hozzátettem még: – Így kell hát körülbelül elképzelni. – Ö meg erre, ugyanúgy, mint elöbb, csak cigaretta helyett, amit idöközben eldobott már, ezúttal az arcát tartva mind a két kezében, s talán etto”l még tompább, még fojtottabb hangon azt mondta: – Nem, nem lehet elképzelni –, s részemröl ezt be is láttam. Gondoltam is: akkor hát, úgy látszik, ezért mondanak helyette inkább poklot, bizonyára.

Imre Kertész

Onbepaald door het lot (Dutch)

Bij het station aangekomen, stapte ik op de tram omdat ik last kreeg van mijn voeten, bovendien was het een lijn die ik van vroeger kende. Op het open balkon ging een magere, oude vrouw met een eigenaardige, ouderwetse kanten kraag haastig opzij toen ze me zag. Weldra verscheen er een man met een pet en een uniform, die mijn kaartje wilde zien. Ik zei dat ik uit het buitenland kwam en geen geld bij me had. Hij monsterde mijn jas, keek eerst mij aan en vervolgens de oude vrouw en zei toen dat er bepaalde voorschriften golden voor het passagiersvervoer, die overigens niet door hem, maar ‘door de lui boven hem’ waren gemaakt. Als ik geen geld had voor een kaartje, moest ik de tram verlaten. Ik antwoordde dat ik pijn in mijn voeten had, waarop de oude vrouw haar blik afwendde en naar de straat keek, alsof ze beledigd was door mijn woorden, ja alsof ik haar een verwijt had gemaakt. Op dat ogenblik ging de tussendeur van het rijtuig open en kwam er een zwaar gebouwde, donkerharige man met een verwaarloosd uiterlijk het balkon op gestommeld die iets onverstaanbaars riep. Hij droeg een overhemd zonder stropdas en een lichtgekleurd linnen pak en had een aktentas in zijn hand. Aan een riem om zijn schouder hing iets wat eruitzag als een zwarte doos. ‘Wat heeft dat te betekenen?’ riep hij, en tegen de conducteur snauwde hij: ‘Geef die jongen oumiddellijk een kaartje!’ terwijl hij hem met een nogal bruusk gebaar een geldstuk overhandigde, of liever gezegd: toestopte. Ik wilde hem bedanken, maar hij onderbrak mij nog steeds boos om zich heen kijkend, en zei: ‘Bepaalde mensen hier zouden zich moeten schamen.’ De conducteur was echter al doorgelopen en de oude vrouw staarde nog steeds aandachtig naar de straat. Toen hij dit zag, wendde hij zich met een veel vriendelijker gezicht naar mij en vroeg: ‘Kom je net terug uit Duitsland, mijn jongen?’ ‘Ja’, zei ik. ‘Uit een concentratiekamp?’ ‘Natuurlijk.’ ‘Welk kamp?’ ‘Buchenwald.’ Hij zei dat hij daarvan had gehoord en noemde het een der meest beruchte krochten van de nazi-hel. ‘Waar ben je opgepakt?’ ‘In Boedapest.’ ‘Hoe lang heb je in het kamp gezeten?’ ‘Alles bij elkaar één jaar.’ ‘Die ogen van je zullen heel wat gezien hebben, jongen, veel gruwelijks’, zei hij toen hij dit hoorde, waarop ik niets terugzei. ‘Gelukkig is het nu allemaal voorbij’, vervolgde hij, en met een opgewekt gezicht naar de huizen wijzend waar de tram tussendoor ratelde, vroeg hij wat fik voelde nu ik weer thuis was en de stad terugzag. Ik zei: ‘Haat.’ Even zweeg hij, maar toen zei hij dat hij vreesde mijn gevoelens te moeten begrijpen. Overigens waren haatgevoelens volgens hem ‘in bepaalde situaties’ zeer functioneel en zelfs ‘nuttig’, wat ik waarschijnlijk uit eigen ervaring wel wist. Hij zei ook nog: ‘Ik weet heel goed wie je haat.’ Ik antwoordde: ‘Iedereen.’ Na dit antwoord zweeg hij opnieuw en nu duurde het veel langer voordat hij weer begon te spreken. Hij vroeg: ‘Heb je veel gruwelijke dingen meegemaakt?’ Ik zei hem dat ik die vraag moeilijk kon beantwoorden omdat ik niet wist wat hij met ‘gruwelijk’ bedoelde. ‘Je hebt ongetwijfeld veel ontberingen moeten doorstaan en honger geleden en misschien hebben ze je in het kamp ook geslagen’, zei hij met een enigszins gespannen gelaatsuitdrukking.’ Ik antwoordde: ’Natuurlijk.’ Daarop riep hij luid: ‘Waarom antwoord je op alles wat ik zeg „natuurlijk”, beste jongen, terwijl we het over zaken hebben die helemaal niet natuurlijk zijn?’ Ik had de indruk dat hij op het punt stond zijn geduld te verliezen en zei: ‘In een concentratiekamp zijn ze wel natuurlijk.’ ‘Nu ja, goed, daar misschien wel, maar…’ – op dat punt aangeland bleef hij even steken en aarzelde hij – ‘maar een concentratiekamp is op zichzelf niet natuurlijk.’ Dit laatste zei hij op opgeluchte toon, alsof hij eindelijk het juiste woord had gevonden. Ik gaf geen antwoord omdat ik langzamerhand begon in te zien dat je over sommige zaken eenvoudig niet kon discussiëren met buitenstaanders, die wat de kampen betreft totaal onwetend waren en als kleine kinderen konden worden beschouwd. Toen ik uit het raam keek, zag ik dat we het plein naderden waar ik moest uitstappen. Het lag er nog net zo bij als vroeger, maar de huizen waren wat grauwer en vervelozer dan bij mijn vertrek uit Boedapest en zagen er enigszins verwaarloosd uit. Ik zei tegen de onbekende dat ik mijn bestemming had bereikt en dus afscheid van hem moest nemen, maar hij wilde me kennelijk nog wat langer gezelschap houden en stapte eveneens uit. Buiten wees hij op een overschaduwd bankje waar de rugleuning van was verdwenen en hij stelde voor om daar even te gaan zitten.

Aanvankelijk wist hij niet goed hoe hij van wal moest steken. ‘Eigenlijk’, merkte hij op, ‘komen al die gruwelen nu pas aan het licht’, en hij voegde eraan toe ‘dat de wereld zich verbijsterd afvroeg hoe dit alles had kunnen gebeuren.’ Ik zei niets, waarop hij zich geheel naar mij toekeerde en onverwachts vroeg: ‘Zou je de mensen niet willen vertellen wat je allemaal hebt meegemaakt, mijn jongen?’ Ik was nogal verbaasd door deze vraag en antwoordde dat ik hem niet veel interessants te vertellen had, maar hij glimlachte flauwtjes en zei: ‘Niet mij, maar de wereld.’ Nog meer verbaasd dan eerst vroeg ik: ‘Maar wát zou ik dan moeten vertellen?’ ‘Wat een hel het concentratiekamp was’, antwoordde hij, waarop ik opmerkte dat ik daar niets over wist te zeggen omdat ik de hel niet kende en me die ook absoluut niet kon voorstellen. Hij zei daarop dat dit ook maar een vergelijking was. ‘Is een concentratiekamp dan geen hel?’ vroeg hij, en ik antwoordde met mijn hak kringetjes in het stof trekkend dat iedereen natuurlijk vrij was om zich bepaalde voorstellingen te maken, maar dat ik alleen wist wat een concentratiekamp was, althans ertigszins, doordat ik daar zelf in had gezeten, maar dat ik me bij het woord ‘hel’ niets kon voorstellen. ‘Maar als je je de hel toch probeert voor te stellen, hoe ziet die er dan uit?’ hield hij aan en ik antwoordde na nog wat nieuwe kringetjes te hebben getrokken: ‘Als een plaats waar je je niet kunt vervelen, en dat kon je in de kampen wel, zelfs in Auschwitz in bepaalde omstandigheden.’ Daarop zweeg hij enige tijd en vervolgens vroeg hij, bijna met tegenzin naar het scheen: ‘Heb je daar een verklaring voor?’ Na even nagedacht te hebben antwoordde ik: ‘Dat komt door de tijd.’ ‘Door de tijd? Wat bedoel je daarmee?’ ‘Ik bedoel dat de tijd helpt.’ ‘Helpt? Waarmee dan?’ ‘Met alles.’ Ik probeerde hem uit te leggen wat het was om op een misschien niet luxueus maar in elk geval acceptabel, goed onderhouden en schoon station aan te komen, waar de werkelijkheid pas langzaam en geleidelijk, als het ware stukje bij beetje, tot je doordrong. Zodra je een brokstukje van het geheel aan de weet was gekomen, diende zich alweer het volgende aan en tegen de tijd dat je alles wist, begreep je ook alles. Intussen keek je niet werkeloos toe, je deed wat je te doen stond, leefde, handelde, spande je in en trachtte aan de eisen te voldoen die bij elke nieuwe graad van inzicht hoorden. Als dit niet zo was geweest, als je niet geleidelijk met de werkelijkheid was geconfronteerd, maar door al die kennis onmiddellijk bij aankomst was overspoeld, hadden je hersenen en je hart dat waarschijnlijk niet kunnen verdragen. In dergelijke bewoordingen trachtte ik hem duidelijk te maken wat het is om in een concentratiekamp te zitten, waarop hij een rafelig kartonnen doosje uit zijn zak opdiepte en me een verfomfaaide sigaret aanbood, die ik niet accepteerde. Hij stak zelf wel op, maar na de rook tweemaal diep geïnhaleerd te hebben boog hij zijn bovenlichaam voorover, legde zijn ellebogen op zijn knieën en zei zonder me aan te kijken, op enigszins doffe, moedeloze toon: ‘Ik begrijp het.’ ‘Aan de andere kant’, vervolgde ik, ‘werkte de tijd ook tegen je, of laat ik zeggen in je nadeel, want je moest hem zien door te komen. Ik heb gevangenen gezien die al vier, zes of meer jaren in het kamp zaten, beter gezegd nog in het kamp zaten, en sommigen zelfs twaalf jaar. Deze mensen moesten vier, zes of twaalf lange jaren doorkomen, in het laatste geval dus twaalfmaal driehonderdvijfenzestig dagen, oftewel twaalfmaal driehonderdvijfenzestig maal vierentwintig uren, dat wil zeggen twaalfmaal driehonderdvijfenzestig maal vierentwintig… enzovoort. Al die seconden, minuten, uren, dagen, die hele lange tijd, moesten ze het op de een of andere manier zien vol te houden. En toch… toch was dit juist hun geluk, want als ze die onmetelijke hoeveelheid van twaalfmaal driehonderdvijfenzestig maal vierentwintig maal zestig maal nog eens zestig seconden in één keer over zich uitgestort hadden gekregen, waren ze daar vast niet tegen bestand geweest, lichamelijk noch geestelijk, terwijl ze dat nu wel waren.’ ‘Toen de man bleef zwijgen, voegde ik er nog aan toe: ’Zo moet u zich dat ongeveer voorstellen.’ Hiecrop gooide hij zijn sigaret weg en zei, nog steeds in dezelfde gebogen houding gezeten maar met zijn handen zijn gezicht bedekkend: ‘Nee, ik kán me dat niet voorstellen!’ Zijn stem klonk nog doffer dan daarstraks, bijna verstikt, zodat ik begreep dat hij daar werkelijk niet toe in staat was. Ik dacht: daarom noemen buitenstaanders de kampen natuurlijk graag een hel.

Henry Kammer

Publisher Van Gennep, Amsterdam

Source of the quotation p. 226-231.

Imre Kertész

Fateless (English)

On reaching the train station, I climbed aboard a streetcar because my leg was hurting and because I recognized one out of many with a familiar number. A thin old woman wearing a strange, old-fashioned lace collar moved away from me. Soon a man came by with a hat and a uniform and asked to see my ticket. I told him I had none. He insisted that I should buy one. I said I had just come back from abroad and was penniless. He looked at my coat, then at me, then at the old woman, and then he informed me that there were rules governing public transportation that not he but people above him had made. He said that if I didn’t buy a ticket, I’d have to get off. I told him my leg ached, and I noticed that the old woman responded to this by turning to look outside the window, in an insulted way, as if I were somehow accusing her of who knows what. Then through the car’s open door a large, black-haired man noisily galloped in. He wore a shirt without a tie and a light canvas suit. From his shoulder a black box hung, and an attaché case was in his hand. „What a shame!” he shouted. „Give him a ticket,” he ordered, and he gave or rather pushed a coin toward the conductor. I tried to thank him, but he interrupted me, looking around, annoyed: „Some people ought to be ashamed of themselves!” he said, but the conductor was already gone. The old woman continued to stare outside.

Then with a softened voice he said to me: „Are you coming from Germany, son?” „Yes,” I said. „From a concentration camp?” „Yes, of course.” „Which one?” „Buchenwald.” „Yes,” he answered, he had heard of it-one of the „pits of Nazi hell.” „Where did they carry you away from?” „Budapest.” „How long were you there?” „One year.” „You must have seen a lot, son, a lot of terrible things,” he said, but I didn’t reply. „Anyway,” he went on, „what’s important is that it’s over, it’s finished,” and with a cheerful face pointing to the buildings that we were passing, he asked me to tell him what I now felt, being home again, seeing the city I had left. I answered, „Hatred.” He fell silent, but soon he observed that, unfortunately, he had to say that he understood how I felt. He also felt that „under certain circumstances” there is a place and a role for hatred, „even a benefit,” and, he added, he assumed that we understood each other, and he knew full well the people I hated. I told him, „Everyone.” Then he fell silent again, this time for a longer period, and then he asked: „Did you have to go through many horrors?” I answered, „That depends on what you call a horror.” Surely, he replied with a tense face, I had been deprived of a lot, had gone hungry, and had probably been beaten. I said, „Naturally.” „Why do you keep saying ‘naturally,’ son,” he exclaimed, seeming to lose his temper, „when you are referring to things that are not natural at all?” „In a concentration camp,” I said, „they are very natural.” „Yes, yes,” he gasped, „it’s true there, but … well … but the concentration camp itself is not natural.” He seemed to have found the appropriate expression, but I didn’t even answer him, because I began to understand that there are certain subjects you can’t discuss, it seems, with strangers, ignorant people, and children, one might say. Besides – I suddenly noticed an unchanged, only slightly more bare and uncared-for square – it was time for me to get off, and I told him so. But he came after me, and pointing to a backless bench over in the shade, he suggested, „Let’s sit down for a minute.”

First he seemed somewhat insecure. „To tell the truth,” he observed, „it’s only now that the horrors are beginning to surface, and the world is still standing speechless and without understanding before the question How could all this have happened?” I was quiet, but he turned toward me and said: „Son, wouldn’t you like to tell me about your experiences?” I was a little surprised and told him that I couldn’t tell him very many interesting things. Then he smiled a little and said, „Not to me, to the world.” Even more astonished, I replied, „What should I talk about?” „The hell of the camps,” he replied, but I answered that I couldn’t say anything about that because I didn’t know anything about hell and couldn’t even imagine what it was like. He assured me that this was simply a metaphor. „Shouldn’t we picture the concentration camp like hell?” he asked. I answered, while drawing circles in the dust with my heels, that people were free to ignore it according to their means and pleasure but that, as far as I was concerned, I was only able to picture the concentration camp because I knew it a bit, but I didn’t know hell at all. „But, still, if you tried,” he insisted. After a few more circles, I answered, „In that case I’d imagine it as a place where you can’t be bored. But,” I added, „you can be bored in a concentration camp, even in Auschwitz – given, of course, certain circumstances.” Then he fell silent and asked, almost as if it was against his will: „How do you explain that?” After giving it some thought, I said, „By the time.” „What do you mean `by the time’?” „Because time helps.” „Helps? How?” „It helps in every way.”

I tried to explain how fundamentally different it is, for instance, to be arriving at a station that is spectacularly white, clean, and neat, where everything becomes clear only gradually, step by step, on schedule. As we pass one step, and as we recognize it as being behind us, the next one already rises up before us. By the time we learn everything, we slowly come to understand it. And while you come to understand everything gradually, you don’t remain idle at any moment: you are already attending to your new business; you live, you act, you move, you fulfill the new requirements of every new step of development. If, on the other hand, there were no schedule, no gradual enlightenment, if all the knowledge descended on you at once right there in one spot, then it’s possible neither your brains nor your heart could bear it. I tried to explain this to him as he fished out a torn package from his pocket and offered me a wrinkled cigarette, which I declined. Then, after two large inhalations, supporting his elbows on his knees with his upper body leaning forward, he said, without looking at me, in a colorless, dull voice: „I understand.”

„On the other hand,” I continued, „there is the unfortunate disadvantage that you somehow have to pass away the time. I’ve seen prisoners who were there for 4, 6, or even 12 years or more who were still hanging on in the camp. And these people had to spend these 4, 6, or 12 years times 365 days-that is, 12 times 365 times 24 hours – in other words, they had to somehow occupy the time by the second, the minute, the day. But then again,” I added, „that may have been precisely what helped them too, because if the whole time period had descended on them in one fell swoop, they probably wouldn’t have been able to bear it, either physically or mentally, the way they did.” Because he was silent, I added: „You have to imagine it this way.” He answered the same as before, except now he covered his face with his hands, threw the cigarette away, and then said in a somewhat more subdued, duller voice: „No, you can’t imagine it.” I, for my part, thought to myself. „That’s probably why they say `hell’ instead.”

Christopher C. Wilson, Katharina M. Wilson

Wilson, Katharina M.; Wilson, Christopher C.

Imre Kertész

Los utracony (Polish)

Dochodza;c do dworca, poniewaz. noga zaczyna?a juz. porza;dnie dawac’ mi sie; we znaki, a takz.e dlatego, z.e w?as’nie zatrzyma? sie; przede mna; jeden ze znanych mi z dawna numerów, wsiad?em do tramwaju. Na otwartym pomos’cie sta?a nieco z boku chuda, stara kobieta w dziwacznym, staromodnym koronkowym ko?nierzu. Wkrótce przyszed? jakis’ cz?owiek, w czapce, w mundurze, i poprosi? o bilet. Powiedzia?em mu: – Nie mam. – Zaproponowa?, z.ebym kupi?. Rzek?em: – Nie mam pienie;dzy. – Wtedy przyjrza? sie; mojej kurtce, mnie, potem równiez. starej kobiecie, i poinformowa? mnie, z.e jazda tramwajem ma swoje prawa i te prawa wymys’li? nie on, lecz ci, którzy stoja; nad nirn. – Jes’li pan nie wykupi biletu, musi pan wysia;s’c’ – orzek?. Powiedzia?em mu: – Ale przeciez. boli mnie noga – i wtedy zauwaz.y?em, z.e stara kobieta odwróci?a sie; i patrzy?a na ulice; z obraz.ona; mina;, jakbym mia? do niej pretensje, nie wiadomo dlaczego. Ale przez otwarte drzwi wagonu wpad?, czynia;c juz. z daleka wielki ha?as, postawny, czarnow?osy, rozczochrany me;z.czyzna. Nosi? rozpie;ta; koszule; i jasny p?ócienny garnitur, na ramieniu zawieszone na pasku czarne pude?ko i teczce; w re;ku. – Co tu sie; dzieje? – wykrzykna;? i zarza;dzi?: – Niech mu pan da bilet – wycia;gaja;c, raczej wpychaja;c konduktorowi pienia;dze. Próbowa?em podzie;kowac’, ale mi przerwa?, rozgla;daja;c sie; ze z?os’cia; dooko?a: – Raczej niektórzy powinni sie; wstydzic’ – oznajmi?, ale konduktor by? juz. w s’rodku, a stara kobieta nadal patrzy?a na ulice;. Wtedy ze z?agodnia?a; twarza; zwróci? sie; do mnie. Zapyta?: – Wracasz z Niemiec, synu? – Talc.- Zobozu?- Oczywis’cie.- Zktórego?- Z Buchenwaldu. – Tak, juz. o nim s?ysza?, wie, to takz.e „by?o dno nazistowskiego piek?a”, powiedzia?. – Ska;d cie; wiez’li? – Z Budapesztu. – Jak d?ugo tam by?es’? – Rok, ca?y rok. – Musia?es’ duz.o widziec’, synku, duz.o okrucien’stw -rzek?, a ja nic nie odpowiedzia?em. – No, ale – cia;gna;? – najwaz.niejsze, z.e to juz. koniec, mine;?o – i wskazuja;c z pojas’nia?a; twarza; domy, obok których w?as’nie przejez.dz.alis’my, zainteresowa? sie;: co teraz czuje;, znów w domu i na widok miasta, które opus’ci?em? Odpar?em mu: – Nienawis’c’. – Zamilk?, ale wkrótce zauwaz.y?, z.e niestety rozumie moje uczucia. Nawiasem mówia;c, wed?ug niego „w danej sytuacji” nienawis’c’ takz.e ma swoje miejsce i role;, „jest nawet poz.yteczna”, i przypuszcza, doda?, z.e sie; zgadzamy i on dobrze wie, kogo nienawidze;. Powiedzia?em mu: – Wszystkich. – Znów zamilk?, tym razem na d?uz.ej, a potem zacza;? na nowo: – Przeszed?es’ wiele potwornos’ci? – a ja odpar?em, z.e zalez.y, co uwaz.a za potwornos’c’. Na pewno, powiedzia? na to z troche; zaz.enowana; mina;, musia?em duz.o biedowac’, g?odowac’, i prawdopodobnie mnie takz.e bita, a ja mu powiedzia?em: – Oczywis’cie. – Dlaczego, synu – wykrzykna;? i widzia?em, z.e juz. traci cierpliwos’c’ – mówisz na wszystko „oczywis’cie”, i to zawsze wtedy, kiedy cos’ w ogóle nie jest oczywiste?! – Rzek?em: – W obozie koncentracyjnym jest oczywiste. – Tak, tak – on -tam tak, ale… – i utkna;?, zawaha? sie; troche;- ale… przeciez. sam obóz koncentracyjny nie jest oczywisty! – jakby wreszcie znalaz? w?as’ciwe s?owa, i nic mu nie odpowiedzia?em, poniewaz. z wolna zaczyna?em pojmowac’: o takich czy innych rzeczach nie dyskutuje sie; z obcymi, nies’wiadomymi, w pewnym sensie dziec’mi, z.e tak powiem. Zreszta; dostrzeg?em niezmiennie be;da;cy na swoim miejscu i tylko troche; bardziej pusty, bardziej zaniedbany plac: pora wysiadac’, i powiedzia?em mu o tym. AIe wysiad? ze mna; i wskazuja;c nieco dalsza;, zacieniona; ?awke;, która straci?a oparcie, zaproponowa?: – Moz.e usiedlibys’my na minutke;.

Najpierw mia? troche; niepewna; mine;. W istocie, zauwaz.y?, dopiero teraz zaczynaja; sie; „naprawde; ujawniac’ koszmary”, i doda?, z.e „s’wiat stoi na razie bezrozumnie przed pytaniem: jak, w jaki sposób mog?o sie; to wszystko w ogóle zdarzyc'”. Nic nie powiedzia?em, wtedy odwróci? sie; do mnie i nagle zapyta?: – Nie zechcia?bys’, synku, zrelacjonowac’ swoich przez.yc’? – Troche; sie; zdziwi?em i odpar?em, z.e w?as’ciwie nie mia?bym mu nic szczególnie ciekawego do powiedzenia. Na to sie; lekko us’miechna;? i powiedzia?: – Nie mnie, s’wiatu – na co jeszcze bardziej zdziwiony zapyta?em: – Ale o czym? – O piekle obozów – odpar?, na co zauwaz.y?em, z.e o tym to juz. w ogóle nic nie móg?bym powiedziec’, poniewaz. nie znam piek?a i nawet nie potrafi?bym go sobie wyobrazic’. Ale on oznajmi?, z.e to tylko taka przenos’nia: – Czyz. nie jako piek?o- spyta?- wyobraz.amy sobie obóz koncentracyjny? – a ja mu na to, zakres’laja;c przy tym obcasem kilka kó?ek w kurzu, z.e piek?o kaz.dy moz.e sobie wyobraz.ac’ na swój sposób i jes’li o mnie chodzi, to potrafie; sobie wyobrazic’ tylko obóz koncentracyjny, bo obóz troche; znam, piek?a natomiast nie. – Ale, gdyby, powiedzmy, jednak? – upiera? sie; i po kilku nowych kó?kach odpar?em: – To wyobraz.a?bym sobie, z.e jest to takie miejsce, gdzie nie moz.na sie; nudzic’, w obozie zas’ – doda?em -by?o moz.na, nawet w Os’wie;cimiu, rzecz jasna w pewnych warunkach. – Troche; milcza?, a potem jeszcze zapyta?, ale wyczu?em, z’e juz. jakos’ niemal wbrew woli: – Czym to t?umaczysz? – i po krótkim namys’le oznajmi?em: – Czasem. – Dlaczego czasem? – Bo czas pomaga. – Pomaga?… W czym?- We wszystkim – i próbowa?em mu wyt?umaczyc’, jaka to ca?kiem inna sprawa przyjechac’, na przyk?ad, na jes’li nawet nie wspania?a;, to ca?kiem do przyje;cia, czysta;, schludna; stacje;, gdzie powolutku, w porza;dku chronologicznym, stopniowo zaczyna sie; nam wszystko klarowac’. Kiedy mamy za soba; jeden etap, juz. przychodzi naste;pny. Kiedy sie; wszystkiego dowiemy, to rozumiemy tez. wszystko. A kiedy sie; cz?owiek wszystkiego dowiaduje, nie pozostaje bezczynny: wykonuje nowe zadanie, z.yje, dzia?a, porusza sie;, spe?nia wszystkie nowe wymagania wszystkich nowych etapów. Gdyby natomiast nie by?o tej chronologii i gdyby ca?a wiedza rune;?a nam na g?owe; od razu tam na stacji, to moz.e nie wytrzyma?aby tego ani g?owa, ani serce, próbowa?em mu jakos’ wyjas’nic’, na co wycia;gna;wszy z kieszeni poszarpana; paczke;, podsuna;? mi pogniecione papierosy, ale odmówi?em, patem zacia;gna;? sie; mocno dwa razy i opieraja;c ?okcie na kolanach, pochylony, nawet na mnie nie patrza;c, powiedzia? jakims’ troche; matowym, g?uchym g?osem: – Rozumiem. – Z drugiej strony – cia;gna;?em – wada;, powiedzia?bym, b?e;dem, jest to, z.e trzeba wype?nic’ czas. Widzia?em na przyk?ad – powiedzia?em mu – wie;z’niów, którzy cztery, szes’c’, a nawet dwanas’cie lat byli juz., a dok?adniej, wcia;z. jeszcze byli, w obozie. Otóz. ci ludzie musieli jakos’ wype?nic’ te cztery, szes’c’ czy dwanas’cie lat, czyli w ostatnim przypadku dwanas’cie razy po trzysta szes’c’dziesia;t pie;c’ dni, to jest dwanas’cie razy trzysta szes’c’dziesia;t pie;c’ razy dwadzies’cia cztery godziny, dalej: dwanas’cie razy trzysta szes’c’dziesia;t pie;c’ razy dwadzies’cia cztery razy… i wszystko od nowa, co chwile;, minute;, godzine;, dzien’, czyli z.e musza; ca?y ten czas jakos’ wype?nic’. Z drugiej natomiast strony- cia;gna;?em dalej – w?as’nie to mog?o im pomóc, bo gdyby ten ca?y czas, to znaczy dwanas’cie razy trzysta szes’c’dziesia;t pie;c’, razy dwadzies’cia cztery razy szes’c’dziesia;t i znów razy szes’c’dziesia;t, zlecia? im jednoczes’nie i za jednym zamachem na kark, to na pewno nie byliby tacy, jak sa;, ani jes’li idzie o g?owe;, ani o cia?o. – A poniewaz. milcza?, doda?em jeszcze: – A wie;c tak to mniej wie;cej trzeba sobie wyobraz.ac’. – A on na to tak samo jak przedtem, tylko zamiast papierosa, którego juz. tymczasem wyrzuci?, tym razem trzymaja;c w obu d?oniach twarz i moz.e przez to jeszcze bardziej g?uchym i jeszcze bardziej st?umionym g?osem powiedzia?: – Nie, nie moz.na sobie wyobrazic’ – i ja ze swojej strony zrozumia?em go. Pomys’la?em tez.: zatem, jak widac’, dlatego zamiast „obóz” mówia; „piek?o”, na pewno.

Pisarska, Krystyna

Source of the quotation : Los utracony, p. 250-255., WAB, Varsó, 2001

FLEURSDUMAL.NL MAGAZINE

More in: Archive K-L, Kertész, Imre

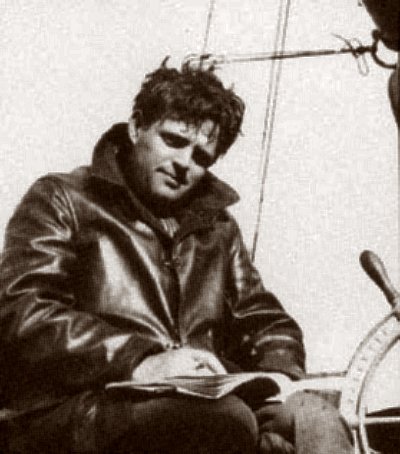

Jack London

(1876-1916)

The Water Baby

I lent a weary ear to old Kohokumu’s interminable chanting of the

deeds and adventures of Maui, the Promethean demi-god of Polynesia

who fished up dry land from ocean depths with hooks made fast to

heaven, who lifted up the sky whereunder previously men had gone on

all-fours, not having space to stand erect, and who made the sun

with its sixteen snared legs stand still and agree thereafter to

traverse the sky more slowly–the sun being evidently a trade

unionist and believing in the six-hour day, while Maui stood for

the open shop and the twelve-hour day.

“Now this,” said Kohokumu, “is from Queen Lililuokalani’s own

family mele:

“Maui became restless and fought the sun

With a noose that he laid.

And winter won the sun,

And summer was won by Maui . . . “

Born in the Islands myself, I knew the Hawaiian myths better than

this old fisherman, although I possessed not his memorization that

enabled him to recite them endless hours.

“And you believe all this?” I demanded in the sweet Hawaiian

tongue.

“It was a long time ago,” he pondered. “I never saw Maui with my

own eyes. But all our old men from all the way back tell us these

things, as I, an old man, tell them to my sons and grandsons, who

will tell them to their sons and grandsons all the way ahead to

come.”

“You believe,” I persisted, “that whopper of Maui roping the sun

like a wild steer, and that other whopper of heaving up the sky

from off the earth?”

“I am of little worth, and am not wise, O Lakana,” my fisherman

made answer. “Yet have I read the Hawaiian Bible the missionaries

translated to us, and there have I read that your Big Man of the

Beginning made the earth, and sky, and sun, and moon, and stars,

and all manner of animals from horses to cockroaches and from

centipedes and mosquitoes to sea lice and jellyfish, and man and

woman, and everything, and all in six days. Why, Maui didn’t do

anything like that much. He didn’t make anything. He just put

things in order, that was all, and it took him a long, long time to

make the improvements. And anyway, it is much easier and more

reasonable to believe the little whopper than the big whopper.”

And what could I reply? He had me on the matter of reasonableness.

Besides, my head ached. And the funny thing, as I admitted it to

myself, was that evolution teaches in no uncertain voice that man

did run on all-fours ere he came to walk upright, that astronomy

states flatly that the speed of the revolution of the earth on its

axis has diminished steadily, thus increasing the length of day,

and that the seismologists accept that all the islands of Hawaii

were elevated from the ocean floor by volcanic action.

Fortunately, I saw a bamboo pole, floating on the surface several

hundred feet away, suddenly up-end and start a very devil’s dance.

This was a diversion from the profitless discussion, and Kohokumu

and I dipped our paddles and raced the little outrigger canoe to

the dancing pole. Kohokumu caught the line that was fast to the

butt of the pole and under-handed it in until a two-foot ukikiki,

battling fiercely to the end, flashed its wet silver in the sun and

began beating a tattoo on the inside bottom of the canoe. Kohokumu

picked up a squirming, slimy squid, with his teeth bit a chunk of

live bait out of it, attached the bait to the hook, and dropped

line and sinker overside. The stick floated flat on the surface of

the water, and the canoe drifted slowly away. With a survey of the

crescent composed of a score of such sticks all lying flat,

Kohokumu wiped his hands on his naked sides and lifted the

wearisome and centuries-old chant of Kuali:

“Oh, the great fish-hook of Maui!

Manai-i-ka-lani–“made fast to the heavens”!

An earth-twisted cord ties the hook,

Engulfed from lofty Kauiki!

Its bait the red-billed Alae,

The bird to Hina sacred!

It sinks far down to Hawaii,

Struggling and in pain dying!

Caught is the land beneath the water,

Floated up, up to the surface,

But Hina hid a wing of the bird

And broke the land beneath the water!

Below was the bait snatched away

And eaten at once by the fishes,

The Ulua of the deep muddy places!

His aged voice was hoarse and scratchy from the drinking of too

much swipes at a funeral the night before, nothing of which

contributed to make me less irritable. My head ached. The sun-

glare on the water made my eyes ache, while I was suffering more

than half a touch of mal de mer from the antic conduct of the

outrigger on the blobby sea. The air was stagnant. In the lee of

Waihee, between the white beach and the roof, no whisper of breeze

eased the still sultriness. I really think I was too miserable to

summon the resolution to give up the fishing and go in to shore.

Lying back with closed eyes, I lost count of time. I even forgot

that Kohokumu was chanting till reminded of it by his ceasing. An

exclamation made me bare my eyes to the stab of the sun. He was

gazing down through the water-glass.

“It’s a big one,” he said, passing me the device and slipping over-

side feet-first into the water.

He went under without splash and ripple, turned over and swam down.

I followed his progress through the water-glass, which is merely an

oblong box a couple of feet long, open at the top, the bottom

sealed water-tight with a sheet of ordinary glass.

Now Kohokumu was a bore, and I was squeamishly out of sorts with

him for his volubleness, but I could not help admiring him as I

watched him go down. Past seventy years of age, lean as a

toothpick, and shrivelled like a mummy, he was doing what few young

athletes of my race would do or could do. It was forty feet to

bottom. There, partly exposed, but mostly hidden under the bulge

of a coral lump, I could discern his objective. His keen eyes had

caught the projecting tentacle of a squid. Even as he swam, the

tentacle was lazily withdrawn, so that there was no sign of the

creature. But the brief exposure of the portion of one tentacle

had advertised its owner as a squid of size.

The pressure at a depth of forty feet is no joke for a young man,

yet it did not seem to inconvenience this oldster. I am certain it

never crossed his mind to be inconvenienced. Unarmed, bare of body

save for a brief malo or loin cloth, he was undeterred by the

formidable creature that constituted his prey. I saw him steady

himself with his right hand on the coral lump, and thrust his left

arm into the hole to the shoulder. Half a minute elapsed, during

which time he seemed to be groping and rooting around with his left

hand. Then tentacle after tentacle, myriad-suckered and wildly

waving, emerged. Laying hold of his arm, they writhed and coiled

about his flesh like so many snakes. With a heave and a jerk

appeared the entire squid, a proper devil-fish or octopus.

But the old man was in no hurry for his natural element, the air

above the water. There, forty feet beneath, wrapped about by an

octopus that measured nine feet across from tentacle-tip to

tentacle-tip and that could well drown the stoutest swimmer, he

coolly and casually did the one thing that gave to him and his

empery over the monster. He shoved his lean, hawk-like face into

the very centre of the slimy, squirming mass, and with his several

ancient fangs bit into the heart and the life of the matter. This

accomplished, he came upward, slowly, as a swimmer should who is

changing atmospheres from the depths. Alongside the canoe, still

in the water and peeling off the grisly clinging thing, the

incorrigible old sinner burst into the pule of triumph which had

been chanted by the countless squid-catching generations before

him:

“O Kanaloa of the taboo nights!

Stand upright on the solid floor!

Stand upon the floor where lies the squid!

Stand up to take the squid of the deep sea!

Rise up, O Kanaloa!

Stir up! Stir up! Let the squid awake!

Let the squid that lies flat awake! Let the squid that lies spread

out . . . “

I closed my eyes and ears, not offering to lend him a hand, secure

in the knowledge that he could climb back unaided into the unstable

craft without the slightest risk of upsetting it.

“A very fine squid,” he crooned. “It is a wahine” (female) “squid.

I shall now sing to you the song of the cowrie shell, the red

cowrie shell that we used as a bait for the squid–“

“You were disgraceful last night at the funeral,” I headed him off.

“I heard all about it. You made much noise. You sang till

everybody was deaf. You insulted the son of the widow. You drank

swipes like a pig. Swipes are not good for your extreme age. Some

day you will wake up dead. You ought to be a wreck to-day–“

“Ha!” he chuckled. “And you, who drank no swipes, who was a babe

unborn when I was already an old man, who went to bed last night

with the sun and the chickens–this day are you a wreck. Explain

me that. My ears are as thirsty to listen as was my throat thirsty

last night. And here to-day, behold, I am, as that Englishman who

came here in his yacht used to say, I am in fine form, in devilish

fine form.”

“I give you up,” I retorted, shrugging my shoulders. “Only one

thing is clear, and that is that the devil doesn’t want you.

Report of your singing has gone before you.”

“No,” he pondered the idea carefully. “It is not that. The devil

will be glad for my coming, for I have some very fine songs for

him, and scandals and old gossips of the high aliis that will make

him scratch his sides. So, let me explain to you the secret of my

birth. The Sea is my mother. I was born in a double-canoe, during

a Kona gale, in the channel of Kahoolawe. From her, the Sea, my

mother, I received my strength. Whenever I return to her arms, as

for a breast-clasp, as I have returned this day, I grow strong

again and immediately. She, to me, is the milk-giver, the life-

source–“

“Shades of Antaeus!” thought I.

“Some day,” old Kohokumu rambled on, “when I am really old, I shall

be reported of men as drowned in the sea. This will be an idle

thought of men. In truth, I shall have returned into the arms of

my mother, there to rest under the heart of her breast until the

second birth of me, when I shall emerge into the sun a flashing

youth of splendour like Maui himself when he was golden young.”

“A queer religion,” I commented.

“When I was younger I muddled my poor head over queerer religions,”

old Kohokumu retorted. “But listen, O Young Wise One, to my

elderly wisdom. This I know: as I grow old I seek less for the

truth from without me, and find more of the truth from within me.

Why have I thought this thought of my return to my mother and of my

rebirth from my mother into the sun? You do not know. I do not

know, save that, without whisper of man’s voice or printed word,

without prompting from otherwhere, this thought has arisen from

within me, from the deeps of me that are as deep as the sea. I am

not a god. I do not make things. Therefore I have not made this

thought. I do not know its father or its mother. It is of old

time before me, and therefore it is true. Man does not make truth.

Man, if he be not blind, only recognizes truth when he sees it. Is

this thought that I have thought a dream?”

“Perhaps it is you that are a dream,” I laughed. “And that I, and

sky, and sea, and the iron-hard land, are dreams, all dreams.”

“I have often thought that,” he assured me soberly. “It may well

be so. Last night I dreamed I was a lark bird, a beautiful singing

lark of the sky like the larks on the upland pastures of Haleakala.

And I flew up, up, toward the sun, singing, singing, as old

Kohokumu never sang. I tell you now that I dreamed I was a lark

bird singing in the sky. But may not I, the real I, be the lark

bird? And may not the telling of it be the dream that I, the lark

bird, am dreaming now? Who are you to tell me ay or no? Dare you

tell me I am not a lark bird asleep and dreaming that I am old

Kohokumu?”

I shrugged my shoulders, and he continued triumphantly:

“And how do you know but what you are old Maui himself asleep and

dreaming that you are John Lakana talking with me in a canoe? And

may you not awake old Maui yourself, and scratch your sides and say

that you had a funny dream in which you dreamed you were a haole?”

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “Besides, you wouldn’t believe me.”

“There is much more in dreams than we know,” he assured me with

great solemnity. “Dreams go deep, all the way down, maybe to

before the beginning. May not old Maui have only dreamed he pulled

Hawaii up from the bottom of the sea? Then would this Hawaii land

be a dream, and you, and I, and the squid there, only parts of

Maui’s dream? And the lark bird too?”

He sighed and let his head sink on his breast.

“And I worry my old head about the secrets undiscoverable,” he

resumed, “until I grow tired and want to forget, and so I drink

swipes, and go fishing, and sing old songs, and dream I am a lark

bird singing in the sky. I like that best of all, and often I

dream it when I have drunk much swipes . . . “

In great dejection of mood he peered down into the lagoon through

the water-glass.

“There will be no more bites for a while,” he announced. “The

fish-sharks are prowling around, and we shall have to wait until

they are gone. And so that the time shall not be heavy, I will

sing you the canoe-hauling song to Lono. You remember:

“Give to me the trunk of the tree, O Lono!

Give me the tree’s main root, O Lono!

Give me the ear of the tree, O Lono!–“

“For the love of mercy, don’t sing!” I cut him short. “I’ve got a

headache, and your singing hurts. You may be in devilish fine form

to-day, but your throat is rotten. I’d rather you talked about

dreams, or told me whoppers.”

“It is too bad that you are sick, and you so young,” he conceded

cheerily. “And I shall not sing any more. I shall tell you

something you do not know and have never heard; something that is

no dream and no whopper, but is what I know to have happened. Not

very long ago there lived here, on the beach beside this very

lagoon, a young boy whose name was Keikiwai, which, as you know,

means Water Baby. He was truly a water baby. His gods were the

sea and fish gods, and he was born with knowledge of the language

of fishes, which the fishes did not know until the sharks found it

out one day when they heard him talk it.

“It happened this way. The word had been brought, and the

commands, by swift runners, that the king was making a progress

around the island, and that on the next day a luau” (feast) “was to

be served him by the dwellers here of Waihee. It was always a

hardship, when the king made a progress, for the few dwellers in

small places to fill his many stomachs with food. For he came

always with his wife and her women, with his priests and sorcerers,

his dancers and flute-players, and hula-singers, and fighting men

and servants, and his high chiefs with their wives, and sorcerers,

and fighting men, and servants.

“Sometimes, in small places like Waihee, the path of his journey

was marked afterward by leanness and famine. But a king must be

fed, and it is not good to anger a king. So, like warning in

advance of disaster, Waihee heard of his coming, and all food-

getters of field and pond and mountain and sea were busied with

getting food for the feast. And behold, everything was got, from

the choicest of royal taro to sugar-cane joints for the roasting,

from opihis to limu, from fowl to wild pig and poi-fed puppies–

everything save one thing. The fishermen failed to get lobsters.

“Now be it known that the king’s favourite food was lobster. He

esteemed it above all kai-kai” (food), “and his runners had made

special mention of it. And there were no lobsters, and it is not

good to anger a king in the belly of him. Too many sharks had come

inside the reef. That was the trouble. A young girl and an old

man had been eaten by them. And of the young men who dared dive

for lobsters, one was eaten, and one lost an arm, and another lost

one hand and one foot.

“But there was Keikiwai, the Water Baby, only eleven years old, but

half fish himself and talking the language of fishes. To his

father the head men came, begging him to send the Water Baby to get

lobsters to fill the king’s belly and divert his anger.

“Now this what happened was known and observed. For the fishermen,

and their women, and the taro-growers and the bird-catchers, and

the head men, and all Waihee, came down and stood back from the

edge of the rock where the Water Baby stood and looked down at the

lobsters far beneath on the bottom.

“And a shark, looking up with its cat’s eyes, observed him, and

sent out the shark-call of ‘fresh meat’ to assemble all the sharks

in the lagoon. For the sharks work thus together, which is why

they are strong. And the sharks answered the call till there were

forty of them, long ones and short ones and lean ones and round

ones, forty of them by count; and they talked to one another,

saying: ‘Look at that titbit of a child, that morsel delicious of

human-flesh sweetness without the salt of the sea in it, of which

salt we have too much, savoury and good to eat, melting to delight

under our hearts as our bellies embrace it and extract from it its

sweet.’

“Much more they said, saying: ‘He has come for the lobsters. When

he dives in he is for one of us. Not like the old man we ate

yesterday, tough to dryness with age, nor like the young men whose

members were too hard-muscled, but tender, so tender that he will

melt in our gullets ere our bellies receive him. When he dives in,

we will all rush for him, and the lucky one of us will get him,

and, gulp, he will be gone, one bite and one swallow, into the

belly of the luckiest one of us.’

“And Keikiwai, the Water Baby, heard the conspiracy, knowing the

shark language; and he addressed a prayer, in the shark language,

to the shark god Moku-halii, and the sharks heard and waved their

tails to one another and winked their cat’s eyes in token that they

understood his talk. And then he said: ‘I shall now dive for a

lobster for the king. And no hurt shall befall me, because the

shark with the shortest tail is my friend and will protect me.

“And, so saying, he picked up a chunk of lava-rock and tossed it

into the water, with a big splash, twenty feet to one side. The

forty sharks rushed for the splash, while he dived, and by the time

they discovered they had missed him, he had gone to bottom and come

back and climbed out, within his hand a fat lobster, a wahine

lobster, full of eggs, for the king.

“‘Ha!’ said the sharks, very angry. ‘There is among us a traitor.

The titbit of a child, the morsel of sweetness, has spoken, and has

exposed the one among us who has saved him. Let us now measure the

lengths of our tails!

“Which they did, in a long row, side by side, the shorter-tailed

ones cheating and stretching to gain length on themselves, the

longer-tailed ones cheating and stretching in order not to be out-

cheated and out-stretched. They were very angry with the one with

the shortest tail, and him they rushed upon from every side and

devoured till nothing was left of him.

“Again they listened while they waited for the Water Baby to dive

in. And again the Water Baby made his prayer in the shark language

to Moku-halii, and said: ‘The shark with the shortest tail is my

friend and will protect me.’ And again the Water Baby tossed in a

chunk of lava, this time twenty feet away off to the other side.

The sharks rushed for the splash, and in their haste ran into one

another, and splashed with their tails till the water was all foam,

and they could see nothing, each thinking some other was swallowing

the titbit. And the Water Baby came up and climbed out with

another fat lobster for the king.

“And the thirty-nine sharks measured tails, devoting the one with

the shortest tail, so that there were only thirty-eight sharks.

And the Water Baby continued to do what I have said, and the sharks

to do what I have told you, while for each shark that was eaten by

his brothers there was another fat lobster laid on the rock for the

king. Of course, there was much quarrelling and argument among the

sharks when it came to measuring tails; but in the end it worked

out in rightness and justice, for, when only two sharks were left,

they were the two biggest of the original forty.

“And the Water Baby again claimed the shark with the shortest tail

was his friend, fooled the two sharks with another lava-chunk, and

brought up another lobster. The two sharks each claimed the other

had the shorter tail, and each fought to eat the other, and the one

with the longer tail won–“

“Hold, O Kohokumu!” I interrupted. “Remember that that shark had

already–“

“I know just what you are going to say,” he snatched his recital

back from me. “And you are right. It took him so long to eat the

thirty-ninth shark, for inside the thirty-ninth shark were already

the nineteen other sharks he had eaten, and inside the fortieth

shark were already the nineteen other sharks he had eaten, and he

did not have the appetite he had started with. But do not forget

he was a very big shark to begin with.

“It took him so long to eat the other shark, and the nineteen

sharks inside the other shark, that he was still eating when

darkness fell, and the people of Waihee went away home with all the

lobsters for the king. And didn’t they find the last shark on the

beach next morning dead, and burst wide open with all he had

eaten?”

Kohokumu fetched a full stop and held my eyes with his own shrewd

ones.

“Hold, O Lakana!” he checked the speech that rushed to my tongue.

“I know what next you would say. You would say that with my own

eyes I did not see this, and therefore that I do not know what I

have been telling you. But I do know, and I can prove it. My

father’s father knew the grandson of the Water Baby’s father’s

uncle. Also, there, on the rocky point to which I point my finger

now, is where the Water Baby stood and dived. I have dived for

lobsters there myself. It is a great place for lobsters. Also,

and often, have I seen sharks there. And there, on the bottom, as

I should know, for I have seen and counted them, are the thirty-

nine lava-rocks thrown in by the Water Baby as I have described.”

“But–” I began.

“Ha!” he baffled me. “Look! While we have talked the fish have

begun again to bite.”

He pointed to three of the bamboo poles erect and devil-dancing in

token that fish were hooked and struggling on the lines beneath.

As he bent to his paddle, he muttered, for my benefit:

“Of course I know. The thirty-nine lava rocks are still there.

You can count them any day for yourself. Of course I know, and I

know for a fact.”

GLEN ELLEN.

October 2, 1916.

From Jack London: ON THE MAKALOA MAT/ISLAND TALES

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, London, Jack

Els Kloek

A.s. zondag 17 maart 2013 om 11.20 uur op Nederland 1

In het boek 1001 vrouwen uit de Nederlandse geschiedenis heeft historica Els Kloek de levensbeschrijvingen van vrouwen verzameld die in de afgelopen eeuwen op een of andere manier naam hebben gemaakt. Bij de samenstelling werd niet alleen gekeken naar bijzondere prestaties, maar ook naar de reputatie waarmee de vrouw de aandacht op zich wist te vestigen.