Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

De Voedselbank (3)

De Voedselbank (3)

‘Loop maar met me mee,’ gebaarde de Engelse en ze stond op om een bos sleutels te halen uit een aangrenzende ruimte die sterk naar wierook en salie geurde. Maureen vertelde dat hier healings plaats vonden. Het hele interieur had ze drie jaar geleden vervangen om een ontspannen sfeer te scheppen, legde ze uit, knabbelend aan een koekje. Om die reden had ze voor vrolijke kleuren gekozen, zoals de IKEA bankstellen met de fleurige kussens en de bonte kleden op de vloer. Op het laatst had ze Piet, een dakloze, de muren laten beschilderen met de gezichten van karikaturale Indianen die tot aan het plafond reikten.

Ze glimlachte bedroefd.

Piet was zo vriendelijk geweest om zichzelf na afloop te belonen met een peperdure gasbarbecue die hij van het terrein af wilde slepen, verklapte Maureen. Helaas voor hem, werd hij in de kraag gegrepen door een van de loonwerkers die ze in dienst had.

Bij de grote bouwvallige schuur op het erf schoof ze een deur open. Met een druk op de knop floepte een tl hoog in het dak aan. De schuur was van eind 19e eeuw, verklaarde Maureen. Het rook er naar dieren en stro. Een ezel balkte, konijnen ritselden in een kooi. Verderop was een camper geparkeerd, een jongere versie van de mijne. Hij was van haar dochter, Jenny. Het was na de echtscheiding lang slecht tussen haar en de kinderen gegaan. En hoewel haar ex-man er meerdere buitenechtelijke relaties op na hield, kreeg Maureen de schuld van het op de klippen gelopen huwelijk. Maar de laatste tijd haalde Jenny haar moeder vaak op om te toeren en herstelde ook het contact met haar andere kinderen gestaag.

Maureen informeerde nogmaals hoe lang ik van plan was te blijven en excuseerde zich voor haar slechte geheugen. Al vier jaar lang had ze een tumor in haar hoofd en hoewel die chemo vereiste, weigerde ze een behandeling. Volgens de prognose had ze morsdood moeten zijn, maar het gezwel leek stil te staan. Ze probeerde er onverschillig onder te blijven, maar door het grijs van haar ogen zweemde oude treurnis. Met een hoofdknik zei ze iets van: ‘Nou je camper in’, en draaide zich om. Achter het keukenraam nam ze plaats, bij het romige schijnsel van een walmende kaars, haar haar zilvergrijs in het bevende licht, haar profiel versteend.

In de camper bedekte ik de ruiten met raamfolie en sloot de blinden. De vorst naderde en stuwde zijn kou naar binnen door alle kieren van mijn tochtige verblijf. Omdat mijn gas op was kon ik de verwarming niet aanzetten, ik moest het doen met een elektrisch tweepitfornuis dat ik ooit kreeg van een Duitser op een camping. De hitte steeg verticaal op van de roodgloeiende spiralen en ofschoon ik bezeten wapperde met een handdoek om de warmte te verspreiden, won de vorst het, die een kille muur opbouwde in het compartiment.

Ik dacht aan Sylvia. Het was augustus. We stonden met de camper op de zonovergoten boulevard van Vlissingen. Met veel vertoon paste Sylvia een paar zomerse jurkjes in de badkamer en speelde ze onzeker te zijn welke te kiezen, want ze wist dat zij de sculptuur was, haar kleding de huid van zand die om haar welvingen golfde. In een rood kanten slipje ging ze zitten op de bank en klapte een spiegeltje uit op tafel om zich op te maken. Op een plankje boven haar hadden mijn dochters schmink en een set kleurpotloden achtergelaten. Het hout bespoten met glitterverf. Speelse glittertjes daalden er nu op Sylvia neer. Van die kleine zilveren speldenpuntjes die het zonlicht op haar zwarte lokken lieten glinsteren en een mysterieuze fonkeling als van maanstof legden op haar huid. Het deed me denken aan de midweek in Parijs, die ik er doorbracht voor het schrijven van een krantenartikel over een tentoonstelling in het Louvre. Op een plein werd ik gelokt door het klateren van een zomerse fontein. Parisiennes in luchtige kledij verfristen zich met het water uit het bassin dat ze in een prismatische nevel over hun hals en armen streken. Waar tussen de gleuf van haar borsten vochtpareltjes glommen, die ik jaren later van Sylvia’s huid kussen mocht.

Ik trok de stekker uit het fornuis. Er was maar een manier om het nog een beetje warm te krijgen: wandelen.

Handschoenen aan, sjaal om, muts op mijn hoofd. De polder in. De akkers waren omgeploegd, de bomen naakt. Het was een grauw landschap. Ik herinnerde mij dat ik hier ’s nachts een keer liep toen het had gesneeuwd en er mist hing over de velden. Door de sneeuw was het of de nacht als een stolp op die witte gloed stond en er tegelijkertijd deel van uitmaakte. Hemel en aarde met elkaar versmolten.

In de stilte knerpten alleen mijn schoenen op het pad. In dit niemandsland voelde ik me een met twee werelden. Zou de dood zo zijn? vroeg ik me af. Opgaan in het luchtledige, ergens blijven zweven tussen het licht en het donker.

Ik naderde de woonwijk waar de echtelijke woning stond.

Dit was het punt waarop ik mij om moest draaien en terugkeren naar Maureens hoeve en mijn camper, maar een onzichtbare hand dwong me verder te lopen. Ik stribbelde niet tegen, ging verder de wijk in. Of wilde ik het gewoon? Verder lopen? En toen ik er opeens stond, voor mijn oude huis, gaf ik het toe aan mezelf: zeg maar hoe klote je je voelt dat je naar je huis staart, hoe de sneeuw op het dak glinstert, de ijsbloemen op de ruiten staan. Waar het licht in de kamers van je dochters brandt, maar het veel te laat is en jij er iets van moet zeggen, naar bed!, licht uit!

Hun fietsen staan nog buiten, leunen scheef tegen de appelboom. Je zou ze eigenlijk achter in de schuur willen zetten. Bedekt onder een laag sneeuw zal het aluminium dat nu nog fonkelt in het lantaarnlicht gaan roesten. Maar je kunt niet eens je eigen tuin in. Je stem in het gezin is je ontnomen, mijn beste, je echo in een mist vergruist.

Het gordijn in Eva’s kamer bewoog en ging langzaam open. Alsof ze voelde dat ik daar stond. Zij en ik. Ik dacht voor altijd met elkaar verbonden. Haar blik zocht mij en vond mijn ogen die zich vulden met iets dat lekker warm was en stroomde. Als een standbeeld stond ze in het raam. Het was niet goed dat ze mij daar zag, die zwerver, die schaduwvlek tegen een muur. Moest ik dan toch naar haar wenken, kusgroeten door de vrieslucht naar haar toe sturen, die op de ruit stuitten en de ijsbloemen lieten smelten?

Ik maakte me los van de muur, liet mijn dochter achter met vraagtekens. En toen ik meters verder omkeek, was het gordijn nog geopend, brandde fel het licht. Maar mij zou ze niet zien. Ik was opgegaan in een tunnel van bomen.

Voor de Voedselbank rolden mensen met gele boodschappenkarren af en aan en laadden ze auto’s vol met tassen die uitpuilden van de etenswaren. Bij de ingang groeide de rij mensen allengs aan. Ze rookten shag, dronken blikjes limonade, en hoewel de sfeer gemoedelijk was, klaagde een enkeling steen en been over het lange wachten en het slechte weer.

De moeder bij wie ik altijd mijn snoep ruilde tegen kaas, was samen met haar dochter. Ze keken opgewonden uit naar het ogenblik dat ze aan de beurt waren, want vandaag ging de limonade voor niks weg, alleen het statiegeld moest betaald worden. Zestien flessen per persoon was de regeling.

Op mijn kaart haalde ik limonade voor de moeder die wat muntstukken in mijn hand drukte en vulde mijn karretje met frisdranken. Toen ik weer buiten kwam, was er tumult. Ik herkende Ronald van de Straatraad. Hij was compleet overstuur.

‘Mijn fiets met achterop mijn tent en slaapzak is een paar dagen geleden gestolen,’ liet hij ons verward weten. ‘En in een zijvak van mijn tent bewaarde ik mijn voedselkaart die nu ook weg is.’

‘Ze kennen je hier toch?’ riep een tandeloos oud vrouwtje met een gammele kinderwagen. Daarin sliep een kind van Aziatische komaf.

‘Natuurlijk kennen ze mij,’ zei Ronald, ‘ik kom hier al jaren, maar het beleid is: geen kaart, geen voedsel. Kan ik net als vroeger mijn eten uit prullenbakken gaan vissen.’

Meteen bood de rij wachtenden aan dat ze hun eten met hem wilden delen.

‘Nee, bedankt,’ weerde hij af. ‘Ik heb liever een plek om te slapen.’

‘Je kan toch naar Doorstroom,’ opperde een Afrikaan met een gedrongen postuur en een buikje.

‘Daar ben ik net geweest en ik had vijf euro bij me voor een overnachting,’ lichtte Ronald toe. ‘Maar de beveiliging liet me niet binnen.’

‘Je hebt recht om daar te slapen,’ wist een Antilliaanse kerel. ‘Je bent toch geen beest dat ze je daar wegsturen.’

‘Helaas heeft Gerard van Centraal Onthaal mij niet aangemeld voor vannacht, dus einde oefening. Want als Hades geen toestemming verleent, verspert Cerberus de toegang tot het schimmenrijk.’

‘Waar moet je nu slapen?’ vroeg de dochter van de moeder met de wagen vol limonadeflessen.

‘Ik heb nog een hutje van takken in het bos. Ik slaap wel onder een bed van bladeren. Al vaker gedaan. Mijn fiets is zo vaak gestolen.’

‘Het gaat vriezen vannacht, Ronald!’ voorspelde een bejaarde corpulente vrouw op een scootmobiel.

Maar hij haalde zijn schouders op en verliet het terrein. Zijn blik was leeg, alsof hij in trance was, lijdzaam overging van leven naar dood.

‘Hallo!’ riep een vrouw bij de Voedselbank tegen mij. Ze duwde een boodschappenkar voort met twee etages aan limonadeflessen omringd door zakken snoep.

‘Wat leuk je weer te zien,’ zei ze en gaf me drie zoenen op mijn wangen.

Vroeger droeg ze strakke mantelpakjes, nu werd haar lijf omhuld door wijde kleren die haar omvang benadrukten.

‘Ik ben er volgende week weer,’ kraaide ze behaagziek, ‘altijd rond tienen.’

Bijna vergat ik in de rij aan te sluiten. Wat als ik haar zou verleiden, dacht ik. Vindt de dakloze zo onderdak via een ontmoeting bij de Voedselbank, juist door het rijke verleden?

Ik keek haar na, hoe ze rammelend het terrein af rolde.

‘Wie was dat?’ wilde een Surinaamse die achter me stond weten. ‘Een buurvrouw of zo?’

‘Nee, dat was een oud collega,’ legde ik uit. ‘Uit de tijd dat we topsalarissen hadden en dikke onkostenvergoedingen.’

Met een boodschappenkarretje betrad ik het uitgiftepunt. Ik had een code op mijn kaart, waaraan de vrijwilligers zagen dat ik alleenstaand was. Langs een rij aaneengeschakelde schooltafels in een L-vorm (had je maar een vak moeten leren!) schuifelden de armoedzaaiers – namen ze de etenswaren in ontvangst.

Weer buiten bevond zich in mijn winkelwagen voor de helft afgedankt voedsel en de andere helft snoep. Door de gigantische voorraad suikerwaar die ik weg gaf aan de moeders op het terrein, maakte ik me snel populair.

Nu was ik behalve een van hen, ook een barmhartige Samaritaan.

EINDE

Niels Landstra

Niels Landstra: De Voedselbank

Niels Landstra (1966) is dichter, schrijver, schilder en muzikant.

De Voedselbank is een bewerkt fragment uit Niels Landstra’s debuutroman: Monddood. Monddood verschijnt in de loop van 2017 bij uitgeverij Droomvallei.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels, Niels Landstra

De Voedselbank (2)

De Voedselbank (2)

Een week later toen ik de camper ging halen, was hij voorzien van een Belgische APK-keuring. Die was beter dan de Nederlandse, dus dat bood extra zekerheid, beweerde de autodealer met zijn zangerige Vlaams. Maar eerst moest ik met zijn echtgenote, een vlotte dame van rond de veertig, naar Brussel toe met de auto. Daar zou ik bij een transitloket een tijdelijke kentekenplaat en documenten ontvangen om het vehikel mee uit te voeren. Het was een rit van vijfenzestig kilometer.

Door een wegomleiding liepen we fikse vertraging op en arriveerden tegen het einde van de ochtend bij het transitkantoor. Mensen hingen er landerig op harde banken, de ambtenaren, waarvan er duidelijk te weinig waren, namen hun tijd, en ook de povere sfeer van stoffig ochtendlicht dat binnenviel op een versleten interieur waar een muffe geur van opsteeg, deed mij denken aan een gemeentekantoor in het voormalig Oostblok.

Ik was anderhalf uur later een paar honderd euro lichter door het afwikkelen van al die formaliteiten. Maar dat tastte mijn humeur niet aan, want toen ik in Namen het terrein af reed met mijn camper, begon mijn vrijheid.

Het was of mijn reis een blanco wegenkaart was. Ongeacht door welk land ik ging toeren, ik had geen plek die mij verplichtte te blijven, geen serene haven om in aan te spoelen, noch keerde ik terug naar die oorlogszone van haat en wrok, die zich samenbalde in negentig kilo vlees dat met enge hakken paradeerde op de houten vloer van de echtelijke woning.

Ik dacht niet langer in termen van een toekomst of schijnzekerheden, ik dacht in het hierna. Hierna zal het beter zijn.

Na een zwerftocht van een paar weken, bracht ik mijn camper naar een APK station. Mijn geïmporteerde huis op wielen zou de Nederlandse nationaliteit krijgen. Gele kentekenplaten die behoorden aan een jaartal dat ik nooit had kunnen betalen als het echt een nieuwe bolide betrof. Maar deze knappe Italiaan was twintig jaar oud.

De garagehouder, Norbert, inspecteerde de camper op de brug. Ondertussen versomberde zijn gezicht. De APK was ver uit beeld, deelde hij mee. Remmen, schokbrekers, gasinstallatie voor de boiler, de kachelmotor in het dashboard: het was allemaal aan vervanging toe. Hij wees mij op een sticker aan de buitenkant van de camper waaruit bleek dat het een verhuurcamper was geweest. Vandaar het hoge kilometrage op de teller. Van de tweehonderdduizend die erop stonden, was er naar schatting de laatste honderdduizend gedraaide kilometers niets aan onderhoud gedaan – dienden de distributieriem, V-snaar en oliekeringen ook te worden vernieuwd.

Norbert gebaarde dat ik achter hem aan moest lopen, de camper in. Hij liet mij de bodem van de douche zien en toonde mij de gaten waarlangs het water in het verleden naar beneden was gestroomd. Het hout daaronder was vochtig en vermolmd. Douchen vermeed ik maar beter, raadde hij mij aan. En de ijskast deed het alleen als de accu hem tijdens het rijden koelde. Maar als hij stil stond, vergeet het maar.

De deurbel ging. Sylvia, mijn hospita, lag boven te slapen. Ze had MS, was te pas en te onpas doodmoe. Ik wilde haar niet storen en deed open. Er stond een Marokkaan voor de deur. Mogelijk was hij van de post, maar toen hij zijn ID liet zien, begreep ik dat hij een Bijzonder OpsporingsAmbtenaar was. Met een rasperige stem en een Ali-B accent informeerde hij of hij met de heer Van Amerongen van doen had. Even ging er door me heen dat hij familie had in Marokko, die, als ze zouden vluchten uit dat land, niet werden teruggestuurd. Dacht ik aan die talloze vluchtelingen uit het Midden Oosten en Afrika die een huis kregen toegewezen en een leven lang een inkomen ontvingen tot hun god ze hier van het aardse kikkerlandparadijs kwam halen.

Of ik mijn camper weg wilde halen van de parkeerplaats, vroeg de ambtenaar. Het vehikel stond erg in de weg volgens de omwonenden die er slecht langs konden met hun rollators, omdat de achterkant zo uitstak. Maar het bedierf ook het straatbeeld, vonden ze.

De Marokkaan probeerde toegeeflijk te zijn. Ik vond dat heel ontwapenend. Vooral toen hij toelichtte dat het niet ging om een enkele klacht, maar een stortvloed aan klachten. Een onhoudbare situatie voor de gemeente. Dit opgeteld bij de verordening dat een kampeerauto maximaal drie dagen op de openbare weg geparkeerd mag staan, dwong hem een proces-verbaal uit te schrijven. Maar hij wilde het deze keer door de vingers zien, stelde de BOA, en opperde dat ik mijn Italiaanse vriend ergens zou kunnen stallen.

‘Ja, goed idee, stallen!’ zei ik enthousiast. ‘Die 100 euro per maand heb ik nog liggen in de oude sok van mijn tante uit Hengelo.’

Handig, dacht ik, sociale controle. Onder die bejaarden in de serviceflat bevindt zich vast nog een handvol verzetsstrijders uit WO II die naar buiten stormen als een licht getinte boef met een bontkraagje in de buurt van mijn Fiat Ducato komt. Sluiten ze mij in de armen met een boksbeugel en een bebloede honkbalknuppel waarmee ze de onschuldige crimineel een kopje kleiner hebben gemaakt. Maar nee, rollators! Een ware klachtenregen!

Op de parkeerplaats startte ik de motor van de camper, die drie dagen niet had gedraaid. Terwijl de rookwolken boven mij optrokken, controleerde ik de banden door er demonstratief tegen aan te trappen. Ondertussen werd het een drukte van belang achter de ramen van het bejaardencomplex. Vriendelijk zwaaide ik naar de silhouetten van verstarde ergernis en opwinding en besloot het afscheid waardig te laten zijn. Met de ruitensproeier spoelde ik het stof van de voorruit en reed van de parkeerplaats af, traag als een slak in een donkere wolk van rook en stank.

Op de weemoedige klanken van een cd met Fado muziek, reed ik weg in de richting van de polder en parkeerde ter hoogte van een recreatieplas waar een bijna landelijke rust heerste. Ganzenkolonies vlogen af en aan, een aalscholver op een verweerde houten paal in het water strekte zijn vleugels ijdel uit. Een man met een hond appte op zijn telefoon, twee jochies met hun moeder achter de kinderwagen, joegen eenden op.

Door de open ramen kabbelde de stilte binnen op een bries, ging op in de muziek, in het bezongen leed van een fadista. Het deed me denken aan het wit tussen dichtregels. Dat het elkaar versterkt op een raadselachtige wijze. Toen ik Sylvia net ontmoet had, vreeën we dagen achtereen, en daartussen lag haar ademen, haar strelen, scheen onze fado geborgd in de stilte en bewaarde ik dat, ook als ik niet bij haar was.

Op den duur verdween die rust, die lafenis. Sylvia kreeg uit het niets paniekaanvallen of hysterische buien die plots kwamen opzetten en even vlug weer afzwakten. Allemaal de schuld van Judith, wist ze. Door de stress die mijn toekomstige ex opwekte, was haar ziekte versneld progressief geworden. Daar twijfelde Sylvia geen moment aan. Maar toen we onlangs bij de neuroloog waren, bleek dat het proces van haar geestelijk verval al vier maanden stil stond. Sommige littekens op haar hersens geslonken.

Ik startte de camper en wilde weg rijden. Maar de voorband draaide nodeloos in de rondte, zakte dieper weg in de modder. Ik stapte uit. Er viel niemand te bekennen om mij hulp te bieden. Dan bleef er nog maar een mogelijkheid over: de ANWB. Die hielpen altijd. De dame van deze organisatie die mij te woord stond aan de telefoon, legde uit dat er een onderscheid was. In het geval van vastraken in de modder restte het ANWB lid niets anders dan een particuliere sleepdienst te bellen. De ANWB was wel goed maar niet gek.

‘Feitelijk heeft u pech,’ besloot de dame, ‘en ik vind het erg lastig voor u dat u uw reis niet kunt vervolgen, maar dit soort pech valt niet onder onze pechhulp.’

Een robuuste kerel met leren laarzen en een groene parka aan, wilde met zijn hond vertrekken in een SUV, maar toonde zich bereid mij eerst te helpen. Het bleek zinloos. De camper was bijna 3000 kilo zwaar en niet onder de indruk van de SUV met zijn sleepkabel.

Hoewel er een lichte onrust in mij ontstond, wandelde ik de polder in, waar ik ongetwijfeld een boer met een tractor zou tegenkomen, ware het niet dat een aantal jaren geleden de laatste boer in de polder was onteigend. Want als de nabij gelegen rivier buiten haar oevers dreigde te treden, moesten de sluizen open kunnen.

Kalm overzag ik de onmogelijkheid van mijn zoektocht, maar liep toch door, ging af op het verre geluid van een tractor.

Op een boerenerf was een jonge kerel met een lawaaierige minitractor balen veevoer aan het optassen. Tevergeefs zwaaide en riep ik naar hem – klom over het houten hek en liep de twintiger met zijn baseballpet op zijn hoofd tegemoet. Maar amper stond ik op het erf, of ik maakte alweer rechtsomkeert om te ontkomen aan een Mechelse herder die blaffend op mij af stormde. In een flits sprong ik over het hek met een lenigheid die me deugd deed en stelde tot mijn vreugde vast dat de jongeman door de waakzame hond mijn kant op keek.

Bij de camper schoot de jongen te binnen dat hij geen sleepkabel had. Een ijzeren stang, onderdeel van de vork aan de voorzijde van de tractor, bood een oplossing. Stevig met elkaar verbonden, trok de pittige landbouwmachine de camper aan zijn trekhaak uit de modder. Met een kleine bocht naar links, zou het plaveisel mijn huis op wielen uit zijn benarde positie bevrijden, maar de jonge boer maakte een stuurfout en de plastic bumper van mijn Fiat klapte vol op de voorkant van de tractor – frommelde in elkaar als een prop papier. Langzaam schoof het achterlicht omhoog, terwijl de bedrading uit de plastic behuizing stulpte.

De tractor was niet verzekerd, bekende de boer onthutst.

Mijn ontgoocheling week voor een mat soort verdriet. Dit was een van die momenten waarop je gewoon je verlies moest nemen. Ik had de camper voor 3000 euro laten repareren. Mijn geld was op.

Tijdens het inloopspreekuur van het Instituut voor Maatschappelijk Welzijn werd ik geholpen door Petra, een maatschappelijk werkster die dit jaar met pensioen ging. Ik legde haar uit dat ik als thuisloze geen recht had op een bijstandsuitkering en ik mijn tijdelijke kamer bij mijn hospita uit moest.

Petra telefoneerde met ene Maureen, een Engelse vrouw die inmiddels op leeftijd was. Vroeger bezorgde ze daklozen een onderkomen op haar boerderij. In principe was ze gestopt met die vorm van dienstverlening, liet de oude landlady aan Petra over de telefoon weten, maar met een camper lag het net even anders. Ze wilde onder voorbehoud met mij kennis maken.

Maureens’ hoeve lag op de rand van een verlaten en waterrijk buitengebied met boerderijen en grazende koeien aan de einder. Maar de landelijke stilte verdween toen ik naderde; het lawaai op de aangrenzende A16 en de HSL richting Rotterdam, zwol aan tot een crescendo van verkeersgedruis.

Ik reed een zandpad op, dat om een kolossale vervallen schuur naar het erf slingerde.

De deurbel deed het niet – ik rammelde met de klepel op de voordeur. Na enig gestommel binnen, ging er een andere deur open. Maureen lachte haar bijna tandeloze mond naar mij bloot en stak ter begroeting een hand naar mij op. De ketting met edelstenen om haar hals, schitterde in het daglicht.

Ik volgde haar een schemerige gang in, die naar katten rook, terwijl een petroleumgeur ons tegemoet walmde. In de keuken pruttelde vlees boven een vuurtje en sprongen de katten van tafel.

Maureen staarde me aan. De oude vrouw met de nepedelstenen aan kettingen om haar hals, schoof haar wrong over een schouder – het wollen vest dat ze droeg was net zo grijs als haar haar.

Ik legde uit dat ik een staplek nodig had, omdat de verwarming op stroom en gas werkte. En dat was niet de enige reden: als de omwonenden merkten dat ik in mijn camper sliep, kreeg ik een boete van de gemeente.

‘Geldt die regel nog steeds?’ vroeg Maureen met een Engels accent. ‘Word je er gewoon bij gelapt door een buurtbewoner.’

‘En mijn vriendin heeft MS. Omdat we het risico lopen bekeurd te worden, is ze voortdurend gespannen en op haar hoede.’

‘Was er ook iets dat speelde in haar jeugd?’ vroeg de landlady.

‘Ja, die verliep niet goed.’

‘Dan heeft ze al chronische stress opgebouwd toen ze jong was. Als je dat op latere leeftijd nog hebt, wordt het van kwaad tot erger.’

Ik toonde een foto van Sylvia. Met gekruiste benen zat ze in een stoel, haar lijf gestoken in een zwarte jurk, weemoedig blikkend in de lens, haar lippen licht rood geverfd.

‘Mooi is ze. Helemaal naturel,’ zei Maureen en boog voorover om haar nog beter te kunnen zien. ‘Ze is een engel. Jouw reddende engel.’

Buiten sloegen de honden aan. Er reed een tractor het erf op.

Niels Landstra: De Voedselbank (2)

wordt vervolgd

Niels Landstra (1966) is dichter, schrijver, schilder en muzikant.

De Voedselbank is een bewerkt fragment uit Niels Landstra’s debuutroman: Monddood. Monddood verschijnt in de loop van 2017 bij uitgeverij Droomvallei.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels, Niels Landstra

De Voedselbank is een bewerkt fragment uit Niels Landstra’s debuutroman: Monddood. Monddood verschijnt in de loop van 2017 bij uitgeverij Droomvallei.

De Voedselbank (1)

De Voedselbank bevond zich in een oud pand naast een kerk, de voormalige pastorie. De bel-etage was te bereiken via een stenen opgaande trap. Net toen ik aan wilde bellen, zwaaide de voordeur voor mij open, stierf een stem weg in een schemerige hal met donkerbruine lambrisering en witte afbladderende wanden. Bij een vestibule met twee deuren, deed een vertrek dienst als kantoor en de andere als ontvangstruimte; door de hoge ramen vielen repen zonlicht met warrelende stofdeeltjes.

Ik had een oploop bij de afhaal van de voormalige pastorie verwacht, een stroom mensen in kringloopkleren en tassen vol eten, rammelende boodschappenkratten en het gerinkel van flessen, maar hier klonk alleen het geroezemoes van een handvol mensen die aan een gemeenschappelijke tafel koffie dronken.

‘Is dit de Voedselbank?’ vroeg ik aan niemand in het bijzonder.

‘Nou, niet helemaal,’ antwoordde een oude vrouw die moeilijk sprak. Haar bovenlip toonde twee stompjes van tanden. ‘Hoe komt u daar nou bij?’

‘Een sociaal werker van de gemeente stuurde mij hier naar toe.’

‘Alleen ongedocumenteerden kunnen hier eten mee krijgen.’

‘O.’

‘Dat zijn mensen zonder geldige identiteitspapieren.’ Ze monsterde mij van top tot teen. ‘Uit welk land komt u?’ informeerde ze.

‘Kopje koffie?’ bood een hoogbejaarde struise dame aan. ‘En gaat u even zitten. Er is een vergadering van de Straatraad.’

Aan een ovale tafel namen druppelsgewijs mannen plaats. Het waren er een stuk of tien, tussen de twintig en ongeveer veertig jaar oud. Omdat al die anderen die op straat leefden bij voorkeur onzichtbaar bleven of nog gelatener waren dan dit gezelschap – ver verwijderd van het aards bestaan alleen nog hoopten op overleving. Of niet.

De twee jongedames die de vergadering openden brachten namens hun maatschappelijke organisatie te berde dat armoede een gezicht moest krijgen. Binnenkort werden er scholen in de regio bezocht om kinderen te laten zien wat de maatschappij met je deed als je in verval was geraakt en je niet langer als ‘volwaardig mens’ werd beschouwd.

De mollige fotograaf van een provinciale krant, stond op met zijn camera in de aanslag. Hij maakte een kiekje van de dames die geposeerd in de lens gluurden.

Daarna fotografeerde hij Arie. Met zijn tweeënveertig jaar was hij de oudste van de aanwezige daklozen. In een slok leegde hij met zijn gehavende gebit een blik bier en schudde in een soort van wanstaltige ijdelheid zijn paardenstaart heen en weer.

Ronald, een treurig ogende donkerharige dertiger met een verpauperd gebit, deed alsof hij niets merkte van de camera en friemelde met zijn vingers. Hij trok rond op zijn fiets en bivakkeerde met zijn tent in het bos. Door een vechtscheiding was hij alles kwijt geraakt, zijn kinderen, geld, en een dak boven zijn hoofd.

Toen de camera op Frank werd gericht, schermde hij met een hand zijn gezicht af. De midden dertiger leefde al tien jaar op straat van de opbrengst uit prullenbakken. Hij zou zich dood schamen tegenover zijn vrienden van de Technische Universiteit als ze hem in deze hoedanigheid aanschouwden.

Arie was de enige die instemde om scholen af te gaan en zijn bestaan als voormalige dakloze over het voetlicht te brengen. Hij wilde alleen niet dat hij op de school van zijn kinderen een lezing moest geven. Als hij was afgekickt van de drank, zou hij overwegen het contact met hen op te pakken, eerder niet. Hij opende zijn tweede blikje Heineken en liep de tuin in om er te roken.

Onder een houten afdak scholen de daklozen voor de regen. Elke verschoppeling had er zijn verhaal. Ergens was het fout gegaan. Een faillissement. Een ziekte die de loopbaan verknalde. Alcoholisme, drugs, gokken. De onvermijdelijke echtscheiding. De vrouw die zonder enige waarheidsvinding toch altijd gelijk krijgt. En voor de man, haast kinderloos verklaard door instanties die altijd meeveren met de moeder van de kinderen, doet de wurggreep van rap oplopende schulden zich voor. Gaat alles voor hem verloren wat eerst heel en volwaardig was. Wie houdt het dan nog vol om niet aan lager wal te geraken?

Ronald gaf toe dat hij worstelde met zijn ‘normale’ bestaan. Toen hij nog volop verwikkeld was in de vechtscheiding, kreeg hij een woning toegewezen en een uitkering in de vorm van leenbijstand die hij later moest terugbetalen als zijn woning was verkocht.

Ronald liep gelijk averij op met het betalen van de huur en kosten voor water en licht, want de gemeente was traag in de afwikkeling van zijn dossier. Gedurende die periode van zes weken kreeg hij 50 euro per week voorgeschoten, maar dat broodgeld stond vaak laat op zijn bankrekening of helemaal niet, zodat hij, hoewel hij nu in een appartement woonde, nog steeds gedwongen was om prullenbakken af te struinen op zoek naar eten.

Maar het geluk leek aan zijn zijde te staan, toen hij een oude schoolvriendin tegen het lijf liep. Net als hij lag ze in echtscheiding, en, samen overgeleverd aan hetzelfde lot, vonden ze troost en warmte bij elkaar, met name in haar woning. Voor de vorm sliep hij enkele dagen in zijn appartement zonder meubels, tv, internet en telefoon, maar dat voorkwam niet dat de sociale recherche ze in de smiezen had en waarnemingen deden, zoals de ambtenaren dat noemden. Ze hielden hun huizen in de gaten, registreerden de tijden waarop hij bij haar was en hoe lang hij in zijn eigen woning verbleef. Het gevolg was dat ze werden gepakt voor bijstandsfraude. Als moeder van twee kleine kinderen raakte ze haar eenoudertoeslag kwijt, zijn uitkering werd gevorderd en hij kreeg een boete. Er volgden incassobureaus, deurwaardersexploten, en tenslotte een huisuitzetting, met politie erbij, wat de deurwaarder een doos met verroeste pannen en een krakkemikkige stoel opleverde.

Ronald kocht van zijn laatste geld een fiets en een tent en hij gooide de sleutel van de woning door de brievenbus: liever de vrijheid van de straat dan de heerszucht van het regime.

De dubbele tuindeur van de voormalige pastorie zwaaide open en een jonge vrouw verscheen buiten. Resoluut nam ze mij bij de arm mee naar het kantoor. Rakelings over de voeten gereden door een zwaarlijvige vrouw in een zoemende scootmobiel, deelde ze mee dat ik hier helemaal verkeerd zat. De officiële Voedselbank was in Noord. Ze vulde een formulier voor een noodvoedselpakket voor me in en meldde me aan. Dat was een beetje tegen de regels in, vertrouwde ze mij toe. Zonder de naam van een maatschappelijk werkster mocht ze dit niet doen. Maar nood breekt wetten, zei ze. Ondertussen pleegde ze een telefoontje voor een Zuid-Amerikaanse moeder en haar dochter die op haar schoot kraaide van plezier. Down syndroom.

Het kon altijd erger, besefte ik, terwijl mijn troosteres met haar handen achteloos over het glanzende haar van het meisje streek. Ze was begin dertig en geen rimpel tekende zich af in haar wasbleke gezicht.

Was zij nou een soort moeder Teresa wier maagdelijke lichaam later op hoge leeftijd ter aarde werd besteld?

In België ging ik kijken naar een camper die te koop stond bij de firma Used Cars in Namen. Tussen de exclusieve Italiaanse auto’s op het terrein van de dealer, met name Ferrari’s, stond de oude camper er als verloren bij.

Ik was op slag verliefd op de witte kampeerbus.

Alles was in goede staat, drukte de verkoper mij op het hart. De omstreeks zestigjarige man ging mij langs een metalen uitklapbaar trapje voor naar binnen toe. Hij toonde mij de badkamer met toilet en douche, die door het witte plastic en de blinkende spiegels een frisse aanblik bood.

Het was heerlijk om na een zomerse dag aan het strand te kunnen douchen in de camper, wist de verkoper, en hij zette de kraan aan waar geen druppel uit kwam.

‘De watertank moet nog worden gevuld,’ zei hij in West-Vlaams dialect, met het inslikken van de n, ‘maar dan hebt ge ook meteen honderd liter bij u.’

De Belg liet mij de keuken van de Fiat Ducato zien. Omdat de ijskast zowel op de accu als op een gasfles werkte, had ik onderweg de beschikking over ijsklontjes en gekoelde dranken: ik zou me in een hotel op wielen wanen, grapte hij. En mochten er kinderen mee gaan, die sliepen prima achterin de camper. De bank was in een handomdraai omgetoverd tot tweepersoonsbed.

Ik zag het al voor me: dat Eva en Hanna met hun slaperige hoofden ontwaakten in een ander land en ik ze trakteerde op een uitgebreid ontbijt met koele glazen jus d’orange.

Op de bijrijdersstoel, met een sacherijnige autoverkoper naast me die de camper bestuurde, maakte ik een proefrit. De Fiat diesel maakte een licht schrapend geluid, alsof er in de motor iets aanliep, maar de verkoper, Giovanni, betoogde met een onvervalste Italiaanse tongval, dat de vorige eigenaren, een hoogbejaard stel, hun bezit had gekoesterd en perfect onderhouden.

Ik vergiste mij vast, dacht ik. Had ik een andere keuze, wie weet wat ik dan gedaan zou hebben, maar die had ik niet, ik moest thuis weg, en als ik dan ging, was dit de beste oplossing.

De psycholoog die ik voor mijn vertrek uit mijn oude huis raadpleegde, Ajeet Raya, was een man van Surinaams Hindoestaanse afkomst met een zonnig karakter. Hij vermaakte zich om mijn relaas over de kenau die ik gehuwd had, maar stelde na enige sessies vast dat mijn psychische problemen situatief waren: de oplossing lag in het loslaten van het oude. Want waarom stelde ik alles zo lang uit? En als ik, zoals ik mij toen had voorgenomen, een camper kocht, had ik weliswaar geen huis, maar toch een dak boven mijn hoofd. Geen enkele situatie is ideaal, besloot hij. Ergens moest ik opnieuw beginnen.

Ik hakte de knoop door.

Niels Landstra: De Voedselbank (1)

wordt vervolgd

Niels Landstra (Ridderkerk, 1966) debuteerde in 2004 in Meander met het kortverhaal ‘Het portret’. Hierna volgden tientallen publicaties van korte verhalen, gedichten en interviews in literaire tijdschriften als De Brakke Hond, Deus ex machina, LAVA, en Op Ruwe Planken.

In 2012 verscheen zijn eerste gedichtenbundel: Waterval bij uitgeverij Oorsprong. In 2013 gevolgd door zijn bundel: Wreed het staren, en in 2014: Nader en Onverklaard. Zijn dichtbundel: Droef het zwieren uitgebracht, een bloemrijke reis, scherend langs momenten en passages vol weemoed, ontgoocheling en romantiek, opgetekend door de dichter tijdens een roerig, zwervend bestaan in een huis op vier wielen, verscheen in september 2016.

De dichter/schrijver/schilder/muzikant was een van de stadsdichters uit het Stadsdichterscollectief Breda, opgericht in 2014. In datzelfde jaar won hij een voorronde van de Poetry/Dobbelslam in Utrecht. In 2016 stond hij op de shortlist van Literairwerk.nl met zijn gedicht Retourbiljetten.

Landstra schildert daarnaast landschappen en stadsgezichten, die hij voorziet van gedichten. Deze zijn te vinden op ansichtkaarten van zijn werk en in zijn dichtbundels.

In 2017 verschijnt zijn debuutroman: Monddood bij uitgeverij Droomvallei. Het kortverhaal: De Voedselbank is daar een bewerkt fragment uit. Monddood is een rauwe, soms cynische roman, waarin de troosteloze absurditeit van het leven onmiskenbaar besloten ligt en haast schrijnend dichtbij komt. Door de elementen van tederheid, lyriek en melancholie die er zorgvuldig doorheen gecomponeerd zijn, ontstaat een modern drama dat balanceert op de wankele fundering van armoede, rouw en breekbare liefde.

Momenteel trekt Niels Landstra met zijn cabarateske theatershow Café De Puzzel door het land. Door zijn gedichten muzikaal te ondersteunen met gitaar en accordeon, en deze zelf te zingen en te declameren, dompelt hij het publiek onder in een stroom van taal en klanken. Niet in het minst doordat hij zijn voorstelling doorvlecht met het betere Nederlandstalige lied en tragikomische acts – ontstaat er een fascinerend geheel dat zich in een hoog tempo op de bühne afspeelt.

‘Dichten zoals je hoopt dat dichters dichten, en beter nog, dat is hoe Niels Landstra dicht’

Wim Daniëls

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels, Niels Landstra

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka

Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer

Die Chinesische Mauer ist an ihrer nördlichsten Stelle beendet worden. Von Südosten und Südwesten wurde der Bau herangeführt und hier vereinigt. Dieses System des Teilbaues wurde auch im Kleinen innerhalb der zwei großen Arbeitsheere, des Ost- und des Westheeres, befolgt. Es geschah das so, daß Gruppen von etwa zwanzig Arbeitern gebildet wurden, welche eine Teilmauer von etwa fünfhundert Metern Länge aufzuführen hatten, eine Nachbargruppe baute ihnen dann eine Mauer von gleicher Länge entgegen. Nachdem dann aber die Vereinigung vollzogen war, wurde nicht etwa der Bau am Ende dieser tausend Meter wieder fortgesetzt, vielmehr wurden die Arbeitergruppen wieder in ganz andere Gegenden zum Mauerbau verschickt. Natürlich entstanden auf diese Weise viele große Lücken, die erst nach und nach langsam ausgefüllt wurden, manche sogar erst, nachdem der Mauerbau schon als vollendet verkündigt worden war. Ja, es soll Lücken geben, die überhaupt nicht verbaut worden sind, eine Behauptung allerdings, die möglicherweise nur zu den vielen Legenden gehört, die um den Bau entstanden sind, und die, für den einzelnen Menschen wenigstens, mit eigenen Augen und eigenem Maßstab infolge der Ausdehnung des Baues unnachprüfbar sind.

Nun würde man von vornherein glauben, es wäre in jedem Sinne vorteilhafter gewesen, zusammenhängend zu bauen oder wenigstens zusammenhängend innerhalb der zwei Hauptteile. Die Mauer war doch, wie allgemein verbreitet wird und bekannt ist, zum Schutze gegen die Nordvölker gedacht. Wie kann aber eine Mauer schützen, die nicht zusammenhängend gebaut ist. Ja, eine solche Mauer kann nicht nur nicht schützen, der Bau selbst ist in fortwährender Gefahr. Diese in öder Gegend verlassen stehenden Mauerteile können immer wieder leicht von den Nomaden zerstört werden, zumal diese damals, geängstigt durch den Mauerbau, mit unbegreiflicher Schnelligkeit wie Heuschrecken ihre Wohnsitze wechselten und deshalb vielleicht einen besseren Überblick über die Baufortschritte hatten als selbst wir, die Erbauer. Trotzdem konnte der Bau wohl nicht anders ausgeführt werden, als es geschehen ist. Um das zu verstehen, muß man folgendes bedenken: Die Mauer sollte zum Schutz für die Jahrhunderte werden; sorgfältigster Bau, Benützung der Bauweisheit aller bekannten Zeiten und Völker, dauerndes Gefühl der persönlichen Verantwortung der Bauenden waren deshalb unumgängliche Voraussetzung für die Arbeit. Zu den niederen Arbeiten konnten zwar unwissende Taglöhner aus dem Volke, Männer, Frauen, Kinder, wer sich für gutes Geld anbot, verwendet werden; aber schon zur Leitung von vier Taglöhnern war ein verständiger, im Baufach gebildeter Mann nötig; ein Mann, der imstande war, bis in die Tiefe des Herzens mitzufühlen, worum es hier ging. Und je höher die Leistung, desto größer die Anforderungen. Und solche Männer standen tatsächlich zur Verfügung, wenn auch nicht in jener Menge, wie sie dieser Bau hätte verbrauchen können, so doch in großer Zahl.

Man war nicht leichtsinnig an das Werk herangegangen. Fünfzig Jahre vor Beginn des Baues hatte man im ganzen China, das ummauert werden sollte, die Baukunst, insbesondere das Maurerhandwerk, zur wichtigsten Wissenschaft erklärt und alles andere nur anerkannt, soweit es damit in Beziehung stand. Ich erinnere mich noch sehr wohl, wie wir als kleine Kinder, kaum unserer Beine sicher, im Gärtchen unseres Lehrers standen, aus Kieselsteinen eine Art Mauer bauen mußten, wie der Lehrer den Rock schützte, gegen die Mauer rannte, natürlich alles zusammenwarf, und uns wegen der Schwäche unseres Baues solche Vorwürfe machte, daß wir heulend uns nach allen Seiten zu unseren Eltern verliefen. Ein winziger Vorfall, aber bezeichnend für den Geist der Zeit.

Ich hatte das Glück, daß, als ich mit zwanzig Jahren die oberste Prüfung der untersten Schule abgelegt hatte, der Bau der Mauer gerade begann. Ich sage Glück, denn viele, die früher die oberste Höhe der ihnen zugänglichen Ausbildung erreicht hatten, wußten jahrelang mit ihrem Wissen nichts anzufangen, trieben sich, im Kopf die großartigsten Baupläne, nutzlos herum und verlotterten in Mengen. Aber diejenigen, die endlich als Bauführer, sei es auch untersten Ranges, zum Bau kamen, waren dessen tatsächlich würdig. Es waren Maurer, die viel über den Bau nachgedacht hatten und nicht aufhörten, darüber nachzudenken, die sich mit dem ersten Stein, den sie in den Boden einsenken ließen, dem Bau verwachsen fühlten. Solche Maurer trieb aber natürlich, neben der Begierde, gründlichste Arbeit zu leisten, auch die Ungeduld, den Bau in seiner Vollkommenheit endlich erstehen zu sehen. Der Taglöhner kennt diese Ungeduld nicht, den treibt nur der Lohn, auch die oberen Führer, ja selbst die mittleren Führer sehen von dem vielseitigen Wachsen des Baues genug, um sich im Geiste dadurch kräftig zu halten. Aber für die unteren, geistig weit über ihrer äußerlich kleinen Aufgabe stehenden Männer, mußte anders vorgesorgt werden. Man konnte sie nicht zum Beispiel in einer unbewohnten Gebirgsgegend, hunderte Meilen von ihrer Heimat, Monate oder gar Jahre lang Mauerstein an Mauerstein fügen lassen; die Hoffnungslosigkeit solcher fleißigen, aber selbst in einem langen Menschenleben nicht zum Ziel führenden Arbeit hätte sie verzweifelt und vor allem wertloser für die Arbeit gemacht. Deshalb wählte man das System des Teilbaues. Fünfhundert Meter konnten etwa in fünf Jahren fertiggestellt werden, dann waren freilich die Führer in der Regel zu erschöpft, hatten alles Vertrauen zu sich, zum Bau, zur Welt verloren. Drum wurden sie dann, während sie noch im Hochgefühl des Vereinigungsfestes der tausend Meter Mauer standen, weit, weit verschickt, sahen auf der Reise hier und da fertige Mauerteile ragen, kamen an Quartieren höherer Führer vorüber, die sie mit Ehrenzeichen beschenkten, hörten den Jubel neuer Arbeitsheere, die aus der Tiefe der Länder herbeiströmten, sahen Wälder niederlegen, die zum Mauergerüst bestimmt waren, sahen Berge in Mauersteine zerhämmern, hörten auf den heiligen Stätten Gesänge der Frommen Vollendung des Baues erflehen. Alles dieses besänftigte ihre Ungeduld. Das ruhige Leben der Heimat, in der sie einige Zeit verbrachten, kräftigte sie, das Ansehen, in dem alle Bauenden standen, die gläubige Demut, mit der ihre Berichte angehört wurden, das Vertrauen, das der einfache, stille Bürger in die einstige Vollendung der Mauer setzte, alles dies spannte die Saiten der Seele. Wie ewig hoffende Kinder nahmen sie dann von der Heimat Abschied, die Lust, wieder am Volkswerk zu arbeiten, wurde unbezwinglich. Sie reisten früher von Hause fort, als es nötig gewesen wäre, das halbe Dorf begleitete sie lange Strecken weit. Auf allen Wegen Gruppen, Wimpel, Fahnen, niemals hatten sie gesehen, wie groß und reich und schön und liebenswert ihr Land war. Jeder Landmann war ein Bruder, für den man eine Schutzmauer baute, und der mit allem, was er hatte und war, sein Leben lang dafür dankte. Einheit! Einheit! Brust an Brust, ein Reigen des Volkes, Blut, nicht mehr eingesperrt im kärglichen Kreislauf des Körpers, sondern süß rollend und doch wiederkehrend durch das unendliche China.

Dadurch also wird das System des Teilbaues verständlich; aber es hatte doch wohl noch andere Gründe. Es ist auch keine Sonderbarkeit, daß ich mich bei dieser Frage so lange aufhalte, es ist eine Kernfrage des ganzen Mauerbaues, so unwesentlich sie zunächst scheint. Will ich den Gedanken und die Erlebnisse jener Zeit vermitteln und begreiflich machen, kann ich gerade dieser Frage nicht tief genug nachbohren.

Zunächst muß man sich doch wohl sagen, daß damals Leistungen vollbracht worden sind, die wenig hinter dem Turmbau von Babel zurückstehen, an Gottgefälligkeit allerdings, wenigstens nach menschlicher Rechnung, geradezu das Gegenteil jenes Baues darstellen. Ich erwähne dies, weil in den Anfangszeiten des Baues ein Gelehrter ein Buch geschrieben hat, in welchem er diese Vergleiche sehr genau zog. Er suchte darin zu beweisen, daß der Turmbau zu Babel keineswegs aus den allgemein behaupteten Ursachen nicht zum Ziele geführt hat, oder daß wenigstens unter diesen bekannten Ursachen sich nicht die allerersten befinden. Seine Beweise bestanden nicht nur aus Schriften und Berichten, sondern er wollte auch am Orte selbst Untersuchungen angestellt und dabei gefunden haben, daß der Bau an der Schwäche des Fundamentes scheiterte und scheitern mußte. In dieser Hinsicht allerdings war unsere Zeit jener längst vergangenen weit überlegen. Fast jeder gebildete Zeitgenosse war Maurer vom Fach und in der Frage der Fundamentierung untrüglich. Dahin zielte aber der Gelehrte gar nicht, sondern er behauptete, erst die große Mauer werde zum erstenmal in der Menschenzeit ein sicheres Fundament für einen neuen Babelturm schaffen. Also zuerst die Mauer und dann der Turm. Das Buch war damals in aller Hände, aber ich gestehe ein, daß ich noch heute nicht genau begreife, wie er sich diesen Turmbau dachte. Die Mauer, die doch nicht einmal einen Kreis, sondern nur eine Art Viertel- oder Halbkreis bildete, sollte das Fundament eines Turmes abgeben? Das konnte doch nur in geistiger Hinsicht gemeint sein. Aber wozu dann die Mauer, die doch etwas Tatsächliches war, Ergebnis der Mühe und des Lebens von Hunderttausenden? Und wozu waren in dem Werk Pläne, allerdings nebelhafte Pläne, des Turmes gezeichnet und Vorschläge bis ins einzelne gemacht, wie man die Volkskraft in dem kräftigen neuen Werk zusammenfassen solle?

Es gab – dieses Buch ist nur ein Beispiel – viel Verwirrung der Köpfe damals, vielleicht gerade deshalb, weil sich so viele möglichst auf einen Zweck hin zu sammeln suchten. Das menschliche Wesen, leichtfertig in seinem Grund, von der Natur des auffliegenden Staubes, verträgt keine Fesselung; fesselt es sich selbst, wird es bald wahnsinnig an den Fesseln zu rütteln anfangen und Mauer, Kette und sich selbst in alle Himmelsrichtungen zerreißen.

Es ist möglich, daß auch diese, dem Mauerbau sogar gegensätzlichen Erwägungen von der Führung bei der Festsetzung des Teilbaues nicht unberücksichtigt geblieben sind. Wir – ich rede hier wohl im Namen vieler – haben eigentlich erst im Nachbuchstabieren der Anordnungen der obersten Führerschaft uns selbst kennengelernt und gefunden, daß ohne die Führerschaft weder unsere Schulweisheit noch unser Menschenverstand für das kleine Amt, das wir innerhalb des großen Ganzen hatten, ausgereicht hätte. In der Stube der Führerschaft – wo sie war und wer dort saß, weiß und wußte niemand, den ich fragte – in dieser Stube kreisten wohl alle menschlichen Gedanken und Wünsche und in Gegenkreisen alle menschlichen Ziele und Erfüllungen. Durch das Fenster aber fiel der Abglanz der göttlichen Welten auf die Pläne zeichnenden Hände der Führerschaft.

Und deshalb will es dem unbestechlichen Betrachter nicht eingehen, daß die Führerschaft, wenn sie es ernstlich gewollt hätte, nicht auch jene Schwierigkeiten hätte überwinden können, die einem zusammenhängenden Mauerbau entgegenstanden. Bleibt also nur die Folgerung, daß die Führerschaft den Teilbau beabsichtigte. Aber der Teilbau war nur ein Notbehelf und unzweckmäßig. Bleibt die Folgerung, daß die Führerschaft etwas Unzweckmäßiges wollte. – Sonderbare Folgerung! – Gewiß, und doch hat sie auch von anderer Seite manche Berechtigung für sich. Heute kann davon vielleicht ohne Gefahr gesprochen werden. Damals war es geheimer Grundsatz Vieler, und sogar der Besten: Suche mit allen deinen Kräften die Anordnungen der Führerschaft zu verstehen, aber nur bis zu einer bestimmten Grenze, dann höre mit dem Nachdenken auf. Ein sehr vernünftiger Grundsatz, der übrigens noch eine weitere Auslegung in einem später oft wiederholten Vergleich fand: Nicht weil es dir schaden könnte, höre mit dem weiteren Nachdenken auf, es ist auch gar nicht sicher, daß es dir schaden wird. Man kann hier überhaupt weder von Schaden noch Nichtschaden sprechen. Es wird dir geschehen wie dem Fluß im Frühjahr. Er steigt, wird mächtiger, nährt kräftiger das Land an seinen langen Ufern, behält sein eignes Wesen weiter ins Meer hinein und wird dem Meere ebenbürtiger und willkommener. – So weit denke den Anordnungen der Führerschaft nach. – Dann aber übersteigt der Fluß seine Ufer, verliert Umrisse und Gestalt, verlangsamt seinen Abwärtslauf, versucht gegen seine Bestimmung kleine Meere ins Binnenland zu bilden, schädigt die Fluren, und kann sich doch für die Dauer in dieser Ausbreitung nicht halten, sondern rinnt wieder in seine Ufer zusammen, ja trocknet sogar in der folgenden heißen Jahreszeit kläglich aus. – So weit denke den Anordnungen der Führerschaft nicht nach.

Nun mag dieser Vergleich während des Mauerbaues außerordentlich treffend gewesen sein, für meinen jetzigen Bericht hat er doch zum mindesten nur beschränkte Geltung. Meine Untersuchung ist doch nur eine historische; aus den längst verflogenen Gewitterwolken zuckt kein Blitz mehr, und ich darf deshalb nach einer Erklärung des Teilbaues suchen, die weitergeht als das, womit man sich damals begnügte. Die Grenzen, die meine Denkfähigkeit mir setzt, sind ja eng genug, das Gebiet aber, das hier zu durchlaufen wäre, ist das Endlose.

Gegen wen sollte die große Mauer schützen? Gegen die Nordvölker. Ich stamme aus dem südöstlichen China. Kein Nordvolk kann uns dort bedrohen. Wir lesen von ihnen in den Büchern der Alten, die Grausamkeiten, die sie ihrer Natur gemäß begehen, machen uns aufseufzen in unserer friedlichen Laube. Auf den wahrheitsgetreuen Bildern der Künstler sehen wie diese Gesichter der Verdammnis, die aufgerissenen Mäuler, die mit hoch zugespitzten Zähnen besteckten Kiefer, die verkniffenen Augen, die schon nach dein Raub zu schielen scheinen, den das Maul zermalmen und zerreißen wird. Sind die Kinder böse, halten wir ihnen diese Bilder hin und schon fliegen sie weinend an unsern Hals. Aber mehr wissen wir von diesen Nordländern nicht. Gesehen haben wir sie nicht, und bleiben wir in unserem Dorf, werden wir sie niemals sehen, selbst wenn sie auf ihren wilden Pferden geradeaus zu uns hetzen und jagen, – zu groß ist das Land und läßt sie nicht zu uns, in die leere Luft werden sie sich verrennen.

Warum also, da es sich so verhält, verlassen wir die Heimat, den Fluß und die Brücken, die Mutter und den Vater, das weinende Weib, die lehrbedürftigen Kinder und ziehen weg zur Schule nach der fernen Stadt und unsere Gedanken sind noch weiter bei der Mauer im Norden? Warum? Frage die Führerschaft. Sie kennt uns. Sie, die ungeheure Sorgen wälzt, weiß von uns, kennt unser kleines Gewerbe, sieht uns alle zusammensitzen in der niedrigen Hütte und das Gebet, das der Hausvater am Abend im Kreise der Seinigen sagt, ist ihr wohlgefällig oder mißfällt ihr. Und wenn ich mir einen solchen Gedanken über die Führerschaft erlauben darf, so muß ich sagen, meiner Meinung nach bestand die Führerschaft schon früher, kam nicht zusammen, wie etwa hohe Mandarinen, durch einen schönen Morgentraum angeregt, eiligst eine Sitzung einberufen, eiligst beschließen, und schon am Abend die Bevölkerung aus den Betten trommeln lassen, um die Beschlüsse auszuführen, sei es auch nur um eine Illumination zu Ehren eines Gottes zu veranstalten, der sich gestern den Herren günstig gezeigt hat, um sie morgen, kaum sind die Lampions verlöscht, in einem dunklen Winkel zu verprügeln. Vielmehr bestand die Führerschaft wohl seit jeher und der Beschluß des Mauerbaues gleichfalls. Unschuldige Nordvölker, die glaubten, ihn verursacht zu haben, verehrungswürdiger, unschuldiger Kaiser, der glaubte, er hätte ihn angeordnet. Wir vom Mauerbau wissen es anders und schweigen.

Ich habe mich, schon damals während des Mauerbaues und nachher bis heute, fast ausschließlich mit vergleichender Völkergeschichte beschäftigt – es gibt bestimmte Fragen, denen man nur mit diesem Mittel gewissermaßen an den Nerv herankommt -und ich habe dabei gefunden, daß wir Chinesen gewisse volkliche und staatliche Einrichtungen in einzigartiger Klarheit, andere wieder in einzigartiger Unklarheit besitzen. Den Gründen, insbesondere der letzten Erscheinung, nachzuspüren, hat mich immer gereizt, reizt mich noch immer, und auch der Mauerbau ist von diesen Fragen wesentlich betroffen.

Nun gehört zu unseren allerundeutlichsten Einrichtungen jedenfalls das Kaisertum. In Peking natürlich, gar in der Hofgesellschaft, besteht darüber einige Klarheit, wiewohl auch diese eher scheinbar als wirklich ist. Auch die Lehrer des Staatsrechtes und der Geschichte an den hohen Schulen geben vor, über diese Dinge genau unterrichtet zu sein und diese Kenntnis den Studenten weitervermitteln zu können. Je tiefer man zu den unteren Schulen herabsteigt, desto mehr schwinden begreiflicherweise die Zweifel am eigenen Wissen, und Halbbildung wogt bergehoch um wenige seit Jahrhunderten eingerammte Lehrsätze, die zwar nichts an ewiger Wahrheit verloren haben, aber in diesem Dunst und Nebel auch ewig unerkannt bleiben.

Gerade über das Kaisertum aber sollte man meiner Meinung nach das Volk befragen, da doch das Kaisertum seine letzten Stützen dort hat. Hier kann ich allerdings wieder nur von meiner Heimat sprechen. Außer den Feldgottheiten und ihrem das ganze Jahr so abwechslungsreich und schön erfüllenden Dienst gilt unser Denken nur dem Kaiser. Aber nicht dem gegenwärtigen; oder vielmehr es hätte dem gegenwärtigen gegolten, wenn wir ihn gekannt, oder Bestimmtes von ihm gewußt hätten. Wir waren freilich – die einzige Neugierde, die uns erfüllte – immer bestrebt, irgend etwas von der Art zu erfahren, aber so merkwürdig es klingt, es war kaum möglich, etwas zu erfahren, nicht vom Pilger, der doch viel Land durchzieht, nicht in den nahen, nicht in den fernen Dörfern, nicht von den Schiffern, die doch nicht nur unsere Flüßchen, sondern auch die heiligen Ströme befahren. Man hörte zwar viel, konnte aber dem Vielen nichts entnehmen.

So groß ist unser Land, kein Märchen reicht an seine Größe, kaum der Himmel umspannt es – und Peking ist nur ein Punkt und das kaiserliche Schloß nur ein Pünktchen. Der Kaiser als solcher allerdings wiederum groß durch alle Stockwerke der Welt. Der lebendige Kaiser aber, ein Mensch wie wir, liegt ähnlich wie wir auf einem Ruhebett, das zwar reichlich bemessen, aber doch möglicherweise nur schmal und kurz ist. Wie wir streckt er manchmal die Glieder, und ist er sehr müde, gähnt er mit seinem zartgezeichneten Mund. Wie aber sollten wir davon erfahren – tausende Meilen im Süden -, grenzen wir doch schon fast ans tibetanischc Hochland. Außerdem aber käme jede Nachricht, selbst wenn sie uns erreichte, viel zu spät, wäre längst veraltet. Um den Kaiser drängt sich die glänzende und doch dunkle Menge des Hofstaates – Bosheit und Feindschaft im Kleid der Diener und Freunde -, das Gegengewicht des Kaisertums, immer bemüht, mit vergifteten Pfeilen den Kaiser von seiner Wagschale abzuschießen. Das Kaisertum ist unsterblich, aber der einzelne Kaiser fällt und stürzt ab, selbst ganze Dynastien sinken endlich nieder und veratmen durch ein einziges Röcheln. Von diesen Kämpfen und Leiden wird das Volk nie erfahren, wie Zu-spät-gekommene, wie Stadtfremde stehen sie am Ende der dichtgedrängten Seitengassen, ruhig zehrend vom mitgebrachten Vorrat, während auf dem Marktplatz in der Mitte weit vorn die Hinrichtung ihres Herrn vor sich geht.

Es gibt eine Sage, die dieses Verhältnis gut ausdrückt. Der Kaiser, so heißt es, hat Dir, dem Einzelnen, dem jämmerlichen Untertanen, dem winzig vor der kaiserlichen Sonne in die fernste Ferne geflüchteten Schatten, gerade Dir hat der Kaiser von seinem Sterbebett aus eine Botschaft gesendet. Den Boten hat er beim Bett niederknien lassen und ihm die Botschaft zugeflüstert; so sehr war ihm an ihr gelegen, daß er sich sie noch ins Ohr wiedersagen ließ. Durch Kopfnicken hat er die Richtigkeit des Gesagten bestätigt. Und vor der ganzen Zuschauerschaft seines Todes – alle hindernden Wände werden niedergebrochen und auf den weit und hoch sich schwingenden Freitreppen stehen im Ring die Großen des Reiches – vor allen diesen hat er den Boten abgefertigt. Der Bote hat sich gleich auf den Weg gemacht; ein kräftiger, ein unermüdlicher Mann; einmal diesen, einmal den andern Arm vorstreckend, schafft er sich Bahn durch die Menge; findet er Widerstand, zeigt er auf die Brust, wo das Zeichen der Sonne ist; er kommt auch leicht vorwärts wie kein anderer. Aber die Menge ist so groß; ihre Wohnstätten nehmen kein Ende. Öffnete sich freies Feld, wie würde er fliegen und bald wohl hörtest Du das herrliche Schlagen seiner Fäuste an Deiner Tür. Aber statt dessen, wie nutzlos müht er sich ab; immer noch zwängt er sich durch die Gemächer des innersten Palastes; niemals wird er sie überwinden; und gelänge ihm dies, nichts wäre gewonnen; die Treppen hinab müßte er sich kämpfen; und gelänge ihm dies, nichts wäre gewonnen; die Höfe wären zu durchmessen; und nach den Höfen der zweite umschließende Palast; und wieder Treppen und Höfe; und wieder ein Palast; und so weiter durch Jahrtausende; und stürzte er endlich aus dem äußersten Tor – aber niemals, niemals kann es geschehen -, liegt erst die Residenzstadt vor ihm, die Mitte der Welt, hochgeschüttet voll ihres Bodensatzes. Niemand dringt hier durch und gar mit der Botschaft eines Toten. – Du aber sitzt an Deinem Fenster und erträumst sie Dir, wenn der Abend kommt.

Genau so, so hoffnungslos und hoffnungsvoll, sieht unser Volk den Kaiser. Es weiß nicht, welcher Kaiser regiert, und selbst über den Namen der Dynastie bestehen Zweifel. In der Schule wird vieles dergleichen der Reihe nach gelernt, aber die allgemeine Unsicherheit in dieser Hinsicht ist so groß, daß auch der beste Schüler mit in sie gezogen wird. Längst verstorbene Kaiser werden in unseren Dörfern auf den Thron gesetzt, und der nur noch im Liede lebt, hat vor kurzem eine Bekanntmachung erlassen, die der Priester vor dem Altare verliest. Schlachten unserer ältesten Geschichte werden jetzt erst geschlagen und mit glühendem Gesicht fällt der Nachbar mit der Nachricht dir ins Haus. Die kaiserlichen Frauen, überfüttert in den seidenen Kissen, von schlauen Höflingen der edlen Sitten entfremdet, anschwellend in Herrschsucht, auffahrend in Gier, ausgebreitet in Wollust, verüben ihre Untaten immer wieder von neuem. Je mehr Zeit schon vergangen ist, desto schrecklicher leuchten alle Farben, und mit lautem Wehgeschrei erfährt einmal das Dorf, wie eine Kaiserin vor Jahrtausenden in langen Zügen ihres Mannes Blut trank.

So verfährt also das Volk mit den vergangenen, die gegenwärtigen Herrscher aber mischt es unter die Toten. Kommt einmal, einmal in einem Menschenalter, ein kaiserlicher Beamter, der die Provinz bereist, zufällig in unser Dorf, stellt im Namen der Regierenden irgendwelche Forderungen, prüft die Steuerlisten, wohnt dem Schulunterricht bei, befragt den Priester über unser Tun und Treiben, und faßt dann alles, ehe er in seine Sänfte steigt, in langen Ermahnungen an die herbeigetriebene Gemeinde zusammen, dann geht ein Lächeln über alle Gesichter, einer blickt verstohlen zum andern und beugt sich zu den Kindern hinab, um sich vom Beamten nicht beobachten zu lassen. Wie, denkt man, er spricht von einem Toten wie von einem Lebendigen, dieser Kaiser ist doch schon längst gestorben, die Dynastie ausgelöscht, der Herr Beamte macht sich über uns lustig, aber wir tun so, als ob wir es nicht merkten, um ihn nicht zu kränken. Ernstlich gehorchen aber werden wir nur unserem gegenwärtigen Herrn, denn alles andere wäre Versündigung. Und hinter der davoneilenden Sänfte des Beamten steigt irgendein willkürlich aus schon zerfallener Urne Gehobener aufstampfend als Herr des Dorfes auf.

Ähnlich werden die Leute bei uns von staatlichen Umwälzungen, von zeitgenössischen Kriegen in der Regel wenig betroffen. Ich erinnere mich hier an einen Vorfall aus meiner Jugend. In einer benachbarten, aber immerhin sehr weit entfernten Provinz war ein Aufstand ausgebrochen. Die Ursachen sind mir nicht mehr erinnerlich, sie sind hier auch nicht wichtig, Ursachen für Aufstände ergeben sich dort mit jedem neuen Morgen, es ist ein aufgeregtes Volk. Und nun wurde einmal ein Flugblatt der Aufständischen durch einen Bettler, der jene Provinz durchreist hatte, in das Haus meines Vaters gebracht. Es war gerade ein Feiertag, Gäste füllten unsere Stuben, in der Mitte saß der Priester und studierte das Blatt. Plötzlich fing alles zu lachen an, das Blatt wurde im Gedränge zerrissen, der Bettler, der allerdings schon reichlich beschenkt worden war, wurde mit Stößen aus dem Zimmer gejagt, alles zerstreute sich und lief in den schönen Tag. Warum? Der Dialekt der Nachbarprovinz ist von dem unseren wesentlich verschieden, und dies drückt sich auch in gewissen Formen der Schriftsprache aus, die für uns einen altertümlichen Charakter haben. Kaum hatte nun der Priester zwei derartige Seiten gelesen, war man schon entschieden. Alte Dinge, längst gehört, längst verschmerzt. Und obwohl – so scheint es mir in der Erinnerung – aus dem Bettler das grauenhafte Leben unwiderleglich sprach, schüttelte man lachend den Kopf und wollte nichts mehr hören. So bereit ist man bei uns, die Gegenwart auszulöschen.

Wenn man aus solchen Erscheinungen folgern wollte, daß wir im Grunde gar keinen Kaiser haben, wäre man von der Wahrheit nicht weit entfernt. Immer wieder muß ich sagen: Es gibt vielleicht kein kaisertreueres Volk als das unsrige im Süden, aber die Treue kommt dem Kaiser nicht zugute. Zwar steht auf der kleinen Säule am Dorfausgang der heilige Drache und bläst huldigend seit Menschengedenken den feurigen Atem genau in die Richtung von Peking – aber Peking selbst ist den Leuten im Dorf viel fremder als das jenseitige Leben. Sollte es wirklich ein Dorf geben, wo Haus an Haus steht, Felder bedeckend, weiter als der Blick von unserem Hügel reicht und zwischen diesen Häusern stünden bei Tag und bei Nacht Menschen Kopf an Kopf? Leichter als eine solche Stadt sich vorzustellen ist es uns, zu glauben, Peking und sein Kaiser wäre eines, etwa eine Wolke, ruhig unter der Sonne sich wandelnd im Laufe der Zeiten.

Die Folge solcher Meinungen ist nun ein gewissermaßen freies, unbeherrschtes Leben. Keineswegs sittenlos, ich habe solche Sittenreinheit, wie in meiner Heimat, kaum jemals angetroffen auf meinen Reisen. – Aber doch ein Leben, das unter keinem gegenwärtigen Gesetze steht und nur der Weisung und Warnung gehorcht, die aus alten Zeiten zu uns herüberreicht.

Ich hüte mich vor Verallgemeinerungen und behaupte nicht, daß es sich in allen zehntausend Dörfern unserer Provinz so verhält oder gar in allen fünfhundert Provinzen Chinas. Wohl aber darf ich vielleicht auf Grund der vielen Schriften, die ich über diesen Gegenstand gelesen habe, sowie auf Grund meiner eigenen Beobachtungen – besonders bei dem Mauerbau gab das Menschenmaterial dem Fühlenden Gelegenheit, durch die Seelen fast aller Provinzen zu reisen – auf Grund alles dessen darf ich vielleicht sagen, daß die Auffassung, die hinsichtlich des Kaisers herrscht, immer wieder und überall einen gewissen und gemeinsamen Grundzug mit der Auffassung in meiner Heimat zeigt. Die Auffassung will ich nun durchaus nicht als eine Tugend gelten lassen, im Gegenteil. Zwar ist sie in der Hauptsache von der Regierung verschuldet, die im ältesten Reich der Erde bis heute nicht imstande war oder dies über anderem vernachlässigte, die Institution des Kaisertums zu solcher Klarheit auszubilden, daß sie bis an die fernsten Grenzen des Reiches unmittelbar und unablässig wirke. Andererseits aber liegt doch auch darin eine Schwäche der Vorstellungs- oder Glaubenskraft beim Volke, welches nicht dazu gelangt, das Kaisertum aus der Pekinger Versunkenheit in aller Lebendigkeit und Gegenwärtigkeit an seine Untertanenbrust zu ziehen, die doch nichts besseres will, als einmal diese Berührung zu fühlen und an ihr zu vergehen.

Eine Tugend ist also diese Auffassung wohl nicht. Um so auffälliger ist es, daß gerade diese Schwäche eines der wichtigsten Einigungsmittel unseres Volkes zu sein scheint; ja, wenn man sich im Ausdruck soweit vorwagen darf, geradezu der Boden, auf dem wir leben. Hier einen Tadel ausführlich begründen, heißt nicht an unserem Gewissen, sondern, was viel ärger ist, an unseren Beinen rütteln. Und darum will ich in der Untersuchung dieser Frage vorderhand nicht weiter gehen.

Franz Kafka

(1883-1924)

Beim Bau der Chinesischen Mauer

fleursdumalnl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

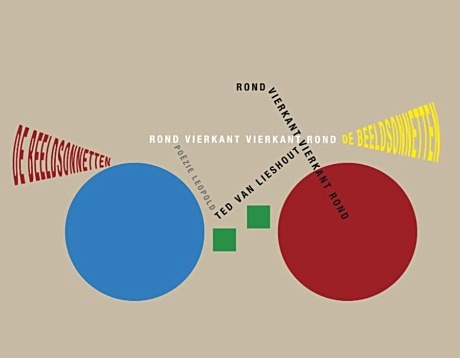

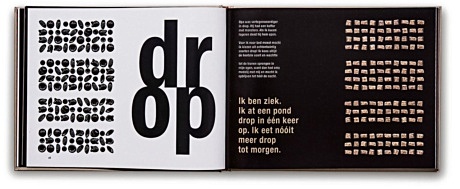

Poëzie is spelen met taal. Maar soms is het maken van een gedicht een lastig spel. Een sonnet, bijvoorbeeld, moet voldoen aan veel regels. Kan dat niet makkelijker? Ja. Want als het niet gaat in letters, dan lukt het wel in beeld!

In dit boek staan naast ‘gewone’ gedichten bijna alle beeldsonnetten die Ted van Lieshout in tien jaar tijd maakte. Maar ook vind je er werk in van kinderen en volwassenen die zich door het beeldsonnet lieten inspireren. En als je tóch een gedicht van taal wilt maken, dan zit je goed met dit boek, want het staat boordevol informatie en tips.

In 2005 verscheen het eerste beeldsonnet van Ted van Lieshout. Na tien jaar bekroont hij het maken van beeldsonnetten met een boek dat niet alleen alle beeldsonnetten bevat, maar ook een keur aan gedichten van taal, aangevuld met geestige informatie over poëzie en hoe je zelf gedichten kunt maken: Rond vierkant vierkant rond.

‘Gedichten, zo mooi dat je ze graag levensgroot aan je muur zou hangen.’ – NRC

Ted van Lieshout: ‘Poëzie is spelen met taal. Maar soms is het maken van een gedicht een lastig spel. Een sonnet, bijvoorbeeld, moet voldoen aan veel regels. Kan dat niet makkelijker? Ja. Want als het niet gaat in letters, dan lukt het wel in beeld!’

De ochtend is nog grauw van mist en kou.

Mijn fiets staat stil te slapen in de schuur.

Ik moet naar school, ik trek hem aan het stuur

naar buiten. ‘Ik ben al laat,’ zeg ik, ‘kom nou!’

Ted van Lieshout

Rond vierkant vierkant rond

De beeldsonnetten

Pagina’s 112

ISBN 978-90-258-6873-4

Leopold – Prijs € 19,99

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, - Book News, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Children's Poetry, Lieshout, Ted van, Ted van Lieshout

The Tomb

The Tomb

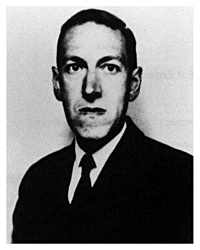

by H. P. Lovecraft

“Sedibus ut saltem placidis in morte quiescam.”

(Virgil)

In relating the circumstances which have led to my confinement within this refuge for the demented, I am aware that my present position will create a natural doubt of the authenticity of my narrative. It is an unfortunate fact that the bulk of humanity is too limited in its mental vision to weigh with patience and intelligence those isolated phenomena, seen and felt only by a psychologically sensitive few, which lie outside its common experience. Men of broader intellect know that there is no sharp distinction betwixt the real and the unreal; that all things appear as they do only by virtue of the delicate individual physical and mental media through which we are made conscious of them; but the prosaic materialism of the majority condemns as madness the flashes of super-sight which penetrate the common veil of obvious empiricism.

My name is Jervas Dudley, and from earliest childhood I have been a dreamer and a visionary. Wealthy beyond the necessity of a commercial life, and temperamentally unfitted for the formal studies and social recreations of my acquaintances, I have dwelt ever in realms apart from the visible world; spending my youth and adolescence in ancient and little-known books, and in roaming the fields and groves of the region near my ancestral home. I do not think that what I read in these books or saw in these fields and groves was exactly what other boys read and saw there; but of this I must say little, since detailed speech would but confirm those cruel slanders upon my intellect which I sometimes overhear from the whispers of the stealthy attendants around me. It is sufficient for me to relate events without analysing causes.

I have said that I dwelt apart from the visible world, but I have not said that I dwelt alone. This no human creature may do; for lacking the fellowship of the living, he inevitably draws upon the companionship of things that are not, or are no longer, living. Close by my home there lies a singular wooded hollow, in whose twilight deeps I spent most of my time; reading, thinking, and dreaming. Down its moss-covered slopes my first steps of infancy were taken, and around its grotesquely gnarled oak trees my first fancies of boyhood were woven. Well did I come to know the presiding dryads of those trees, and often have I watched their wild dances in the struggling beams of a waning moon—but of these things I must not now speak. I will tell only of the lone tomb in the darkest of the hillside thickets; the deserted tomb of the Hydes, an old and exalted family whose last direct descendant had been laid within its black recesses many decades before my birth.

The vault to which I refer is of ancient granite, weathered and discoloured by the mists and dampness of generations. Excavated back into the hillside, the structure is visible only at the entrance. The door, a ponderous and forbidding slab of stone, hangs upon rusted iron hinges, and is fastened ajar in a queerly sinister way by means of heavy iron chains and padlocks, according to a gruesome fashion of half a century ago. The abode of the race whose scions are here inurned had once crowned the declivity which holds the tomb, but had long since fallen victim to the flames which sprang up from a disastrous stroke of lightning. Of the midnight storm which destroyed this gloomy mansion, the older inhabitants of the region sometimes speak in hushed and uneasy voices; alluding to what they call “divine wrath” in a manner that in later years vaguely increased the always strong fascination which I felt for the forest-darkened sepulchre. One man only had perished in the fire. When the last of the Hydes was buried in this place of shade and stillness, the sad urnful of ashes had come from a distant land; to which the family had repaired when the mansion burned down. No one remains to lay flowers before the granite portal, and few care to brave the depressing shadows which seem to linger strangely about the water-worn stones.

I shall never forget the afternoon when first I stumbled upon the half-hidden house of death. It was in mid-summer, when the alchemy of Nature transmutes the sylvan landscape to one vivid and almost homogeneous mass of green; when the senses are well-nigh intoxicated with the surging seas of moist verdure and the subtly indefinable odours of the soil and the vegetation. In such surroundings the mind loses its perspective; time and space become trivial and unreal, and echoes of a forgotten prehistoric past beat insistently upon the enthralled consciousness. All day I had been wandering through the mystic groves of the hollow; thinking thoughts I need not discuss, and conversing with things I need not name. In years a child of ten, I had seen and heard many wonders unknown to the throng; and was oddly aged in certain respects. When, upon forcing my way between two savage clumps of briers, I suddenly encountered the entrance of the vault, I had no knowledge of what I had discovered. The dark blocks of granite, the door so curiously ajar, and the funereal carvings above the arch, aroused in me no associations of mournful or terrible character. Of graves and tombs I knew and imagined much, but had on account of my peculiar temperament been kept from all personal contact with churchyards and cemeteries. The strange stone house on the woodland slope was to me only a source of interest and speculation; and its cold, damp interior, into which I vainly peered through the aperture so tantalisingly left, contained for me no hint of death or decay. But in that instant of curiosity was born the madly unreasoning desire which has brought me to this hell of confinement. Spurred on by a voice which must have come from the hideous soul of the forest, I resolved to enter the beckoning gloom in spite of the ponderous chains which barred my passage. In the waning light of day I alternately rattled the rusty impediments with a view to throwing wide the stone door, and essayed to squeeze my slight form through the space already provided; but neither plan met with success. At first curious, I was now frantic; and when in the thickening twilight I returned to my home, I had sworn to the hundred gods of the grove that at any cost I would some day force an entrance to the black, chilly depths that seemed calling out to me. The physician with the iron-grey beard who comes each day to my room once told a visitor that this decision marked the beginning of a pitiful monomania; but I will leave final judgment to my readers when they shall have learnt all.

The months following my discovery were spent in futile attempts to force the complicated padlock of the slightly open vault, and in carefully guarded inquiries regarding the nature and history of the structure. With the traditionally receptive ears of the small boy, I learned much; though an habitual secretiveness caused me to tell no one of my information or my resolve. It is perhaps worth mentioning that I was not at all surprised or terrified on learning of the nature of the vault. My rather original ideas regarding life and death had caused me to associate the cold clay with the breathing body in a vague fashion; and I felt that the great and sinister family of the burned-down mansion was in some way represented within the stone space I sought to explore. Mumbled tales of the weird rites and godless revels of bygone years in the ancient hall gave to me a new and potent interest in the tomb, before whose door I would sit for hours at a time each day. Once I thrust a candle within the nearly closed entrance, but could see nothing save a flight of damp stone steps leading downward. The odour of the place repelled yet bewitched me. I felt I had known it before, in a past remote beyond all recollection; beyond even my tenancy of the body I now possess.

The year after I first beheld the tomb, I stumbled upon a worm-eaten translation of Plutarch’s Lives in the book-filled attic of my home. Reading the life of Theseus, I was much impressed by that passage telling of the great stone beneath which the boyish hero was to find his tokens of destiny whenever he should become old enough to lift its enormous weight. This legend had the effect of dispelling my keenest impatience to enter the vault, for it made me feel that the time was not yet ripe. Later, I told myself, I should grow to a strength and ingenuity which might enable me to unfasten the heavily chained door with ease; but until then I would do better by conforming to what seemed the will of Fate.

Accordingly my watches by the dank portal became less persistent, and much of my time was spent in other though equally strange pursuits. I would sometimes rise very quietly in the night, stealing out to walk in those churchyards and places of burial from which I had been kept by my parents. What I did there I may not say, for I am not now sure of the reality of certain things; but I know that on the day after such a nocturnal ramble I would often astonish those about me with my knowledge of topics almost forgotten for many generations. It was after a night like this that I shocked the community with a queer conceit about the burial of the rich and celebrated Squire Brewster, a maker of local history who was interred in 1711, and whose slate headstone, bearing a graven skull and crossbones, was slowly crumbling to powder. In a moment of childish imagination I vowed not only that the undertaker, Goodman Simpson, had stolen the silver-buckled shoes, silken hose, and satin small-clothes of the deceased before burial; but that the Squire himself, not fully inanimate, had turned twice in his mound-covered coffin on the day after interment.

But the idea of entering the tomb never left my thoughts; being indeed stimulated by the unexpected genealogical discovery that my own maternal ancestry possessed at least a slight link with the supposedly extinct family of the Hydes. Last of my paternal race, I was likewise the last of this older and more mysterious line. I began to feel that the tomb was mine, and to look forward with hot eagerness to the time when I might pass within that stone door and down those slimy stone steps in the dark. I now formed the habit of listening very intently at the slightly open portal, choosing my favourite hours of midnight stillness for the odd vigil. By the time I came of age, I had made a small clearing in the thicket before the mould-stained facade of the hillside, allowing the surrounding vegetation to encircle and overhang the space like the walls and roof of a sylvan bower. This bower was my temple, the fastened door my shrine, and here I would lie outstretched on the mossy ground, thinking strange thoughts and dreaming strange dreams.

The night of the first revelation was a sultry one. I must have fallen asleep from fatigue, for it was with a distinct sense of awakening that I heard the voices. Of those tones and accents I hesitate to speak; of their quality I will not speak; but I may say that they presented certain uncanny differences in vocabulary, pronunciation, and mode of utterance. Every shade of New England dialect, from the uncouth syllables of the Puritan colonists to the precise rhetoric of fifty years ago, seemed represented in that shadowy colloquy, though it was only later that I noticed the fact. At the time, indeed, my attention was distracted from this matter by another phenomenon; a phenomenon so fleeting that I could not take oath upon its reality. I barely fancied that as I awoke, a light had been hurriedly extinguished within the sunken sepulchre. I do not think I was either astounded or panic-stricken, but I know that I was greatly and permanently changed that night. Upon returning home I went with much directness to a rotting chest in the attic, wherein I found the key which next day unlocked with ease the barrier I had so long stormed in vain.