Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

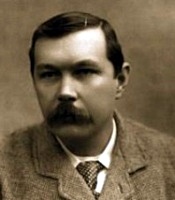

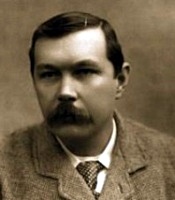

His Last Bow

His Last Bow

by Arthur Conan Doyle

In recording from time to time some of the curious experiences and interesting recollections which I associate with my long and intimate friendship with Mr. Sherlock Holmes, I have continually been faced by difficulties caused by his own aversion to publicity. To his sombre and cynical spirit all popular applause was always abhorrent, and nothing amused him more at the end of a successful case than to hand over the actual exposure to some orthodox official, and to listen with a mocking smile to the general chorus of misplaced congratulation. It was indeed this attitude upon the part of my friend and certainly not any lack of interesting material which has caused me of late years to lay very few of my records before the public. My participation in some of his adventures was always a privilege which entailed discretion and reticence upon me.

It was, then, with considerable surprise that I received a telegram from Holmes last Tuesday—he has never been known to write where a telegram would serve—in the following terms:

Why not tell them of the Cornish horror—strangest case I have handled.

I have no idea what backward sweep of memory had brought the matter fresh to his mind, or what freak had caused him to desire that I should recount it; but I hasten, before another cancelling telegram may arrive, to hunt out the notes which give me the exact details of the case and to lay the narrative before my readers.

It was, then, in the spring of the year 1897 that Holmes’s iron constitution showed some symptoms of giving way in the face of constant hard work of a most exacting kind, aggravated, perhaps, by occasional indiscretions of his own. In March of that year Dr. Moore Agar, of Harley Street, whose dramatic introduction to Holmes I may some day recount, gave positive injunctions that the famous private agent lay aside all his cases and surrender himself to complete rest if he wished to avert an absolute breakdown. The state of his health was not a matter in which he himself took the faintest interest, for his mental detachment was absolute, but he was induced at last, on the threat of being permanently disqualified from work, to give himself a complete change of scene and air. Thus it was that in the early spring of that year we found ourselves together in a small cottage near Poldhu Bay, at the further extremity of the Cornish peninsula.

It was a singular spot, and one peculiarly well suited to the grim humour of my patient. From the windows of our little whitewashed house, which stood high upon a grassy headland, we looked down upon the whole sinister semicircle of Mounts Bay, that old death trap of sailing vessels, with its fringe of black cliffs and surge-swept reefs on which innumerable seamen have met their end. With a northerly breeze it lies placid and sheltered, inviting the storm-tossed craft to tack into it for rest and protection.

Then come the sudden swirl round of the wind, the blistering gale from the south-west, the dragging anchor, the lee shore, and the last battle in the creaming breakers. The wise mariner stands far out from that evil place.

On the land side our surroundings were as sombre as on the sea. It was a country of rolling moors, lonely and dun-colored, with an occasional church tower to mark the site of some old-world village. In every direction upon these moors there were traces of some vanished race which had passed utterly away, and left as its sole record strange monuments of stone, irregular mounds which contained the burned ashes of the dead, and curious earthworks which hinted at prehistoric strife. The glamour and mystery of the place, with its sinister atmosphere of forgotten nations, appealed to the imagination of my friend, and he spent much of his time in long walks and solitary meditations upon the moor. The ancient Cornish language had also arrested his attention, and he had, I remember, conceived the idea that it was akin to the Chaldean, and had been largely derived from the Phoenician traders in tin. He had received a consignment of books upon philology and was settling down to develop this thesis when suddenly, to my sorrow and to his unfeigned delight, we found ourselves, even in that land of dreams, plunged into a problem at our very doors which was more intense, more engrossing, and infinitely more mysterious than any of those which had driven us from London. Our simple life and peaceful, healthy routine were violently interrupted, and we were precipitated into the midst of a series of events which caused the utmost excitement not only in Cornwall but throughout the whole west of England. Many of my readers may retain some recollection of what was called at the time “The Cornish Horror,” though a most imperfect account of the matter reached the London press. Now, after thirteen years, I will give the true details of this inconceivable affair to the public.

I have said that scattered towers marked the villages which dotted this part of Cornwall. The nearest of these was the hamlet of Tredannick Wollas, where the cottages of a couple of hundred inhabitants clustered round an ancient, moss-grown church. The vicar of the parish, Mr. Roundhay, was something of an archaeologist, and as such Holmes had made his acquaintance. He was a middle-aged man, portly and affable, with a considerable fund of local lore. At his invitation we had taken tea at the vicarage and had come to know, also, Mr. Mortimer Tregennis, an independent gentleman, who increased the clergyman’s scanty resources by taking rooms in his large, straggling house. The vicar, being a bachelor, was glad to come to such an arrangement, though he had little in common with his lodger, who was a thin, dark, spectacled man, with a stoop which gave the impression of actual, physical deformity. I remember that during our short visit we found the vicar garrulous, but his lodger strangely reticent, a sad-faced, introspective man, sitting with averted eyes, brooding apparently upon his own affairs.

These were the two men who entered abruptly into our little sitting-room on Tuesday, March the 16th, shortly after our breakfast hour, as we were smoking together, preparatory to our daily excursion upon the moors.

“Mr. Holmes,” said the vicar in an agitated voice, “the most extraordinary and tragic affair has occurred during the night. It is the most unheard-of business. We can only regard it as a special Providence that you should chance to be here at the time, for in all England you are the one man we need.”

I glared at the intrusive vicar with no very friendly eyes; but Holmes took his pipe from his lips and sat up in his chair like an old hound who hears the view-halloa. He waved his hand to the sofa, and our palpitating visitor with his agitated companion sat side by side upon it. Mr. Mortimer Tregennis was more self-contained than the clergyman, but the twitching of his thin hands and the brightness of his dark eyes showed that they shared a common emotion.

“Shall I speak or you?” he asked of the vicar.

“Well, as you seem to have made the discovery, whatever it may be, and the vicar to have had it second-hand, perhaps you had better do the speaking,” said Holmes.

I glanced at the hastily clad clergyman, with the formally dressed lodger seated beside him, and was amused at the surprise which Holmes’s simple deduction had brought to their faces.

“Perhaps I had best say a few words first,” said the vicar, “and then you can judge if you will listen to the details from Mr. Tregennis, or whether we should not hasten at once to the scene of this mysterious affair. I may explain, then, that our friend here spent last evening in the company of his two brothers, Owen and George, and of his sister Brenda, at their house of Tredannick Wartha, which is near the old stone cross upon the moor. He left them shortly after ten o’clock, playing cards round the dining-room table, in excellent health and spirits. This morning, being an early riser, he walked in that direction before breakfast and was overtaken by the carriage of Dr. Richards, who explained that he had just been sent for on a most urgent call to Tredannick Wartha. Mr. Mortimer Tregennis naturally went with him. When he arrived at Tredannick Wartha he found an extraordinary state of things. His two brothers and his sister were seated round the table exactly as he had left them, the cards still spread in front of them and the candles burned down to their sockets. The sister lay back stone-dead in her chair, while the two brothers sat on each side of her laughing, shouting, and singing, the senses stricken clean out of them. All three of them, the dead woman and the two demented men, retained upon their faces an expression of the utmost horror—a convulsion of terror which was dreadful to look upon. There was no sign of the presence of anyone in the house, except Mrs. Porter, the old cook and housekeeper, who declared that she had slept deeply and heard no sound during the night. Nothing had been stolen or disarranged, and there is absolutely no explanation of what the horror can be which has frightened a woman to death and two strong men out of their senses. There is the situation, Mr. Holmes, in a nutshell, and if you can help us to clear it up you will have done a great work.”

I had hoped that in some way I could coax my companion back into the quiet which had been the object of our journey; but one glance at his intense face and contracted eyebrows told me how vain was now the expectation. He sat for some little time in silence, absorbed in the strange drama which had broken in upon our peace.

“I will look into this matter,” he said at last. “On the face of it, it would appear to be a case of a very exceptional nature. Have you been there yourself, Mr. Roundhay?”

“No, Mr. Holmes. Mr. Tregennis brought back the account to the vicarage, and I at once hurried over with him to consult you.”

“How far is it to the house where this singular tragedy occurred?”

“About a mile inland.”

“Then we shall walk over together. But before we start I must ask you a few questions, Mr. Mortimer Tregennis.”

The other had been silent all this time, but I had observed that his more controlled excitement was even greater than the obtrusive emotion of the clergyman. He sat with a pale, drawn face, his anxious gaze fixed upon Holmes, and his thin hands clasped convulsively together. His pale lips quivered as he listened to the dreadful experience which had befallen his family, and his dark eyes seemed to reflect something of the horror of the scene.

“Ask what you like, Mr. Holmes,” said he eagerly. “It is a bad thing to speak of, but I will answer you the truth.”

“Tell me about last night.”

“Well, Mr. Holmes, I supped there, as the vicar has said, and my elder brother George proposed a game of whist afterwards. We sat down about nine o’clock. It was a quarter-past ten when I moved to go. I left them all round the table, as merry as could be.”

“Who let you out?”

“Mrs. Porter had gone to bed, so I let myself out. I shut the hall door behind me. The window of the room in which they sat was closed, but the blind was not drawn down. There was no change in door or window this morning, or any reason to think that any stranger had been to the house. Yet there they sat, driven clean mad with terror, and Brenda lying dead of fright, with her head hanging over the arm of the chair. I’ll never get the sight of that room out of my mind so long as I live.”

“The facts, as you state them, are certainly most remarkable,” said Holmes. “I take it that you have no theory yourself which can in any way account for them?”

“It’s devilish, Mr. Holmes, devilish!” cried Mortimer Tregennis. “It is not of this world. Something has come into that room which has dashed the light of reason from their minds. What human contrivance could do that?”

“I fear,” said Holmes, “that if the matter is beyond humanity it is certainly beyond me. Yet we must exhaust all natural explanations before we fall back upon such a theory as this. As to yourself, Mr. Tregennis, I take it you were divided in some way from your family, since they lived together and you had rooms apart?”

“That is so, Mr. Holmes, though the matter is past and done with. We were a family of tin-miners at Redruth, but we sold our venture to a company, and so retired with enough to keep us. I won’t deny that there was some feeling about the division of the money and it stood between us for a time, but it was all forgiven and forgotten, and we were the best of friends together.”

“Looking back at the evening which you spent together, does anything stand out in your memory as throwing any possible light upon the tragedy? Think carefully, Mr. Tregennis, for any clue which can help me.”

“There is nothing at all, sir.”

“Your people were in their usual spirits?”

“Never better.”

“Were they nervous people? Did they ever show any apprehension of coming danger?”

“Nothing of the kind.”

“You have nothing to add then, which could assist me?”

Mortimer Tregennis considered earnestly for a moment.

“There is one thing occurs to me,” said he at last. “As we sat at the table my back was to the window, and my brother George, he being my partner at cards, was facing it. I saw him once look hard over my shoulder, so I turned round and looked also. The blind was up and the window shut, but I could just make out the bushes on the lawn, and it seemed to me for a moment that I saw something moving among them. I couldn’t even say if it was man or animal, but I just thought there was something there. When I asked him what he was looking at, he told me that he had the same feeling. That is all that I can say.”

“Did you not investigate?”

“No; the matter passed as unimportant.”

“You left them, then, without any premonition of evil?”

“None at all.”

“I am not clear how you came to hear the news so early this morning.”

“I am an early riser and generally take a walk before breakfast. This morning I had hardly started when the doctor in his carriage overtook me. He told me that old Mrs. Porter had sent a boy down with an urgent message. I sprang in beside him and we drove on. When we got there we looked into that dreadful room. The candles and the fire must have burned out hours before, and they had been sitting there in the dark until dawn had broken. The doctor said Brenda must have been dead at least six hours. There were no signs of violence. She just lay across the arm of the chair with that look on her face. George and Owen were singing snatches of songs and gibbering like two great apes. Oh, it was awful to see! I couldn’t stand it, and the doctor was as white as a sheet. Indeed, he fell into a chair in a sort of faint, and we nearly had him on our hands as well.”

“Remarkable—most remarkable!” said Holmes, rising and taking his hat. “I think, perhaps, we had better go down to Tredannick Wartha without further delay. I confess that I have seldom known a case which at first sight presented a more singular problem.”

Our proceedings of that first morning did little to advance the investigation. It was marked, however, at the outset by an incident which left the most sinister impression upon my mind. The approach to the spot at which the tragedy occurred is down a narrow, winding, country lane. While we made our way along it we heard the rattle of a carriage coming towards us and stood aside to let it pass. As it drove by us I caught a glimpse through the closed window of a horribly contorted, grinning face glaring out at us. Those staring eyes and gnashing teeth flashed past us like a dreadful vision.

“My brothers!” cried Mortimer Tregennis, white to his lips. “They are taking them to Helston.”

We looked with horror after the black carriage, lumbering upon its way. Then we turned our steps towards this ill-omened house in which they had met their strange fate.

It was a large and bright dwelling, rather a villa than a cottage, with a considerable garden which was already, in that Cornish air, well filled with spring flowers. Towards this garden the window of the sitting-room fronted, and from it, according to Mortimer Tregennis, must have come that thing of evil which had by sheer horror in a single instant blasted their minds. Holmes walked slowly and thoughtfully among the flower-plots and along the path before we entered the porch. So absorbed was he in his thoughts, I remember, that he stumbled over the watering-pot, upset its contents, and deluged both our feet and the garden path. Inside the house we were met by the elderly Cornish housekeeper, Mrs. Porter, who, with the aid of a young girl, looked after the wants of the family. She readily answered all Holmes’s questions. She had heard nothing in the night. Her employers had all been in excellent spirits lately, and she had never known them more cheerful and prosperous. She had fainted with horror upon entering the room in the morning and seeing that dreadful company round the table. She had, when she recovered, thrown open the window to let the morning air in, and had run down to the lane, whence she sent a farm-lad for the doctor. The lady was on her bed upstairs if we cared to see her. It took four strong men to get the brothers into the asylum carriage. She would not herself stay in the house another day and was starting that very afternoon to rejoin her family at St. Ives.

We ascended the stairs and viewed the body. Miss Brenda Tregennis had been a very beautiful girl, though now verging upon middle age. Her dark, clear-cut face was handsome, even in death, but there still lingered upon it something of that convulsion of horror which had been her last human emotion. From her bedroom we descended to the sitting-room, where this strange tragedy had actually occurred. The charred ashes of the overnight fire lay in the grate. On the table were the four guttered and burned-out candles, with the cards scattered over its surface. The chairs had been moved back against the walls, but all else was as it had been the night before. Holmes paced with light, swift steps about the room; he sat in the various chairs, drawing them up and reconstructing their positions. He tested how much of the garden was visible; he examined the floor, the ceiling, and the fireplace; but never once did I see that sudden brightening of his eyes and tightening of his lips which would have told me that he saw some gleam of light in this utter darkness.

“Why a fire?” he asked once. “Had they always a fire in this small room on a spring evening?”

Mortimer Tregennis explained that the night was cold and damp. For that reason, after his arrival, the fire was lit. “What are you going to do now, Mr. Holmes?” he asked.

My friend smiled and laid his hand upon my arm. “I think, Watson, that I shall resume that course of tobacco-poisoning which you have so often and so justly condemned,” said he. “With your permission, gentlemen, we will now return to our cottage, for I am not aware that any new factor is likely to come to our notice here. I will turn the facts over in my mind, Mr, Tregennis, and should anything occur to me I will certainly communicate with you and the vicar. In the meantime I wish you both good-morning.”

It was not until long after we were back in Poldhu Cottage that Holmes broke his complete and absorbed silence. He sat coiled in his armchair, his haggard and ascetic face hardly visible amid the blue swirl of his tobacco smoke, his black brows drawn down, his forehead contracted, his eyes vacant and far away. Finally he laid down his pipe and sprang to his feet.

“It won’t do, Watson!” said he with a laugh. “Let us walk along the cliffs together and search for flint arrows. We are more likely to find them than clues to this problem. To let the brain work without sufficient material is like racing an engine. It racks itself to pieces. The sea air, sunshine, and patience, Watson—all else will come.

“Now, let us calmly define our position, Watson,” he continued as we skirted the cliffs together. “Let us get a firm grip of the very little which we do know, so that when fresh facts arise we may be ready to fit them into their places. I take it, in the first place, that neither of us is prepared to admit diabolical intrusions into the affairs of men. Let us begin by ruling that entirely out of our minds. Very good. There remain three persons who have been grievously stricken by some conscious or unconscious human agency. That is firm ground. Now, when did this occur? Evidently, assuming his narrative to be true, it was immediately after Mr. Mortimer Tregennis had left the room. That is a very important point. The presumption is that it was within a few minutes afterwards. The cards still lay upon the table. It was already past their usual hour for bed. Yet they had not changed their position or pushed back their chairs. I repeat, then, that the occurrence was immediately after his departure, and not later than eleven o’clock last night.

“Our next obvious step is to check, so far as we can, the movements of Mortimer Tregennis after he left the room. In this there is no difficulty, and they seem to be above suspicion. Knowing my methods as you do, you were, of course, conscious of the somewhat clumsy water-pot expedient by which I obtained a clearer impress of his foot than might otherwise have been possible. The wet, sandy path took it admirably. Last night was also wet, you will remember, and it was not difficult—having obtained a sample print—to pick out his track among others and to follow his movements. He appears to have walked away swiftly in the direction of the vicarage.

“If, then, Mortimer Tregennis disappeared from the scene, and yet some outside person affected the card-players, how can we reconstruct that person, and how was such an impression of horror conveyed? Mrs. Porter may be eliminated. She is evidently harmless. Is there any evidence that someone crept up to the garden window and in some manner produced so terrific an effect that he drove those who saw it out of their senses? The only suggestion in this direction comes from Mortimer Tregennis himself, who says that his brother spoke about some movement in the garden. That is certainly remarkable, as the night was rainy, cloudy, and dark. Anyone who had the design to alarm these people would be compelled to place his very face against the glass before he could be seen. There is a three-foot flower-border outside this window, but no indication of a footmark. It is difficult to imagine, then, how an outsider could have made so terrible an impression upon the company, nor have we found any possible motive for so strange and elaborate an attempt. You perceive our difficulties, Watson?”

“They are only too clear,” I answered with conviction.

“And yet, with a little more material, we may prove that they are not insurmountable,” said Holmes. “I fancy that among your extensive archives, Watson, you may find some which were nearly as obscure. Meanwhile, we shall put the case aside until more accurate data are available, and devote the rest of our morning to the pursuit of neolithic man.”

I may have commented upon my friend’s power of mental detachment, but never have I wondered at it more than upon that spring morning in Cornwall when for two hours he discoursed upon celts, arrowheads, and shards, as lightly as if no sinister mystery were waiting for his solution. It was not until we had returned in the afternoon to our cottage that we found a visitor awaiting us, who soon brought our minds back to the matter in hand. Neither of us needed to be told who that visitor was. The huge body, the craggy and deeply seamed face with the fierce eyes and hawk-like nose, the grizzled hair which nearly brushed our cottage ceiling, the beard—golden at the fringes and white near the lips, save for the nicotine stain from his perpetual cigar—all these were as well known in London as in Africa, and could only be associated with the tremendous personality of Dr. Leon Sterndale, the great lion-hunter and explorer.

We had heard of his presence in the district and had once or twice caught sight of his tall figure upon the moorland paths. He made no advances to us, however, nor would we have dreamed of doing so to him, as it was well known that it was his love of seclusion which caused him to spend the greater part of the intervals between his journeys in a small bungalow buried in the lonely wood of Beauchamp Arriance. Here, amid his books and his maps, he lived an absolutely lonely life, attending to his own simple wants and paying little apparent heed to the affairs of his neighbours. It was a surprise to me, therefore, to hear him asking Holmes in an eager voice whether he had made any advance in his reconstruction of this mysterious episode. “The county police are utterly at fault,” said he, “but perhaps your wider experience has suggested some conceivable explanation. My only claim to being taken into your confidence is that during my many residences here I have come to know this family of Tregennis very well—indeed, upon my Cornish mother’s side I could call them cousins—and their strange fate has naturally been a great shock to me. I may tell you that I had got as far as Plymouth upon my way to Africa, but the news reached me this morning, and I came straight back again to help in the inquiry.”

Holmes raised his eyebrows.

“Did you lose your boat through it?”

“I will take the next.”

“Dear me! that is friendship indeed.”

“I tell you they were relatives.”

“Quite so—cousins of your mother. Was your baggage aboard the ship?”

“Some of it, but the main part at the hotel.”

“I see. But surely this event could not have found its way into the Plymouth morning papers.”

“No, sir; I had a telegram.”

“Might I ask from whom?”

A shadow passed over the gaunt face of the explorer.

“You are very inquisitive, Mr. Holmes.”

“It is my business.”

With an effort Dr. Sterndale recovered his ruffled composure.

“I have no objection to telling you,” he said. “It was Mr. Roundhay, the vicar, who sent me the telegram which recalled me.”

“Thank you,” said Holmes. “I may say in answer to your original question that I have not cleared my mind entirely on the subject of this case, but that I have every hope of reaching some conclusion. It would be premature to say more.”

“Perhaps you would not mind telling me if your suspicions point in any particular direction?”

“No, I can hardly answer that.”

“Then I have wasted my time and need not prolong my visit.” The famous doctor strode out of our cottage in considerable ill-humour, and within five minutes Holmes had followed him. I saw him no more until the evening, when he returned with a slow step and haggard face which assured me that he had made no great progress with his investigation. He glanced at a telegram which awaited him and threw it into the grate.

“From the Plymouth hotel, Watson,” he said. “I learned the name of it from the vicar, and I wired to make certain that Dr. Leon Sterndale’s account was true. It appears that he did indeed spend last night there, and that he has actually allowed some of his baggage to go on to Africa, while he returned to be present at this investigation. What do you make of that, Watson?”

“He is deeply interested.”

“Deeply interested—yes. There is a thread here which we had not yet grasped and which might lead us through the tangle. Cheer up, Watson, for I am very sure that our material has not yet all come to hand. When it does we may soon leave our difficulties behind us.”

Little did I think how soon the words of Holmes would be realized, or how strange and sinister would be that new development which opened up an entirely fresh line of investigation. I was shaving at my window in the morning when I heard the rattle of hoofs and, looking up, saw a dog-cart coming at a gallop down the road. It pulled up at our door, and our friend, the vicar, sprang from it and rushed up our garden path. Holmes was already dressed, and we hastened down to meet him.

Our visitor was so excited that he could hardly articulate, but at last in gasps and bursts his tragic story came out of him.

“We are devil-ridden, Mr. Holmes! My poor parish is devil-ridden!” he cried. “Satan himself is loose in it! We are given over into his hands!” He danced about in his agitation, a ludicrous object if it were not for his ashy face and startled eyes. Finally he shot out his terrible news.

“Mr. Mortimer Tregennis died during the night, and with exactly the same symptoms as the rest of his family.”

Holmes sprang to his feet, all energy in an instant.

“Can you fit us both into your dog-cart?”

“Yes, I can.”

“Then, Watson, we will postpone our breakfast. Mr. Roundhay, we are entirely at your disposal. Hurry—hurry, before things get disarranged.”

The lodger occupied two rooms at the vicarage, which were in an angle by themselves, the one above the other. Below was a large sitting-room; above, his bedroom. They looked out upon a croquet lawn which came up to the windows. We had arrived before the doctor or the police, so that everything was absolutely undisturbed. Let me describe exactly the scene as we saw it upon that misty March morning. It has left an impression which can never be effaced from my mind.

The atmosphere of the room was of a horrible and depressing stuffiness. The servant who had first entered had thrown up the window, or it would have been even more intolerable. This might partly be due to the fact that a lamp stood flaring and smoking on the centre table. Beside it sat the dead man, leaning back in his chair, his thin beard projecting, his spectacles pushed up on to his forehead, and his lean dark face turned towards the window and twisted into the same distortion of terror which had marked the features of his dead sister. His limbs were convulsed and his fingers contorted as though he had died in a very paroxysm of fear. He was fully clothed, though there were signs that his dressing had been done in a hurry. We had already learned that his bed had been slept in, and that the tragic end had come to him in the early morning.

One realized the red-hot energy which underlay Holmes’s phlegmatic exterior when one saw the sudden change which came over him from the moment that he entered the fatal apartment. In an instant he was tense and alert, his eyes shining, his face set, his limbs quivering with eager activity. He was out on the lawn, in through the window, round the room, and up into the bedroom, for all the world like a dashing foxhound drawing a cover. In the bedroom he made a rapid cast around and ended by throwing open the window, which appeared to give him some fresh cause for excitement, for he leaned out of it with loud ejaculations of interest and delight. Then he rushed down the stair, out through the open window, threw himself upon his face on the lawn, sprang up and into the room once more, all with the energy of the hunter who is at the very heels of his quarry. The lamp, which was an ordinary standard, he examined with minute care, making certain measurements upon its bowl. He carefully scrutinized with his lens the talc shield which covered the top of the chimney and scraped off some ashes which adhered to its upper surface, putting some of them into an envelope, which he placed in his pocketbook. Finally, just as the doctor and the official police put in an appearance, he beckoned to the vicar and we all three went out upon the lawn.

“I am glad to say that my investigation has not been entirely barren,” he remarked. “I cannot remain to discuss the matter with the police, but I should be exceedingly obliged, Mr. Roundhay, if you would give the inspector my compliments and direct his attention to the bedroom window and to the sitting-room lamp. Each is suggestive, and together they are almost conclusive. If the police would desire further information I shall be happy to see any of them at the cottage. And now, Watson, I think that, perhaps, we shall be better employed elsewhere.”

It may be that the police resented the intrusion of an amateur, or that they imagined themselves to be upon some hopeful line of investigation; but it is certain that we heard nothing from them for the next two days. During this time Holmes spent some of his time smoking and dreaming in the cottage; but a greater portion in country walks which he undertook alone, returning after many hours without remark as to where he had been. One experiment served to show me the line of his investigation. He had bought a lamp which was the duplicate of the one which had burned in the room of Mortimer Tregennis on the morning of the tragedy. This he filled with the same oil as that used at the vicarage, and he carefully timed the period which it would take to be exhausted. Another experiment which he made was of a more unpleasant nature, and one which I am not likely ever to forget.

“You will remember, Watson,” he remarked one afternoon, “that there is a single common point of resemblance in the varying reports which have reached us. This concerns the effect of the atmosphere of the room in each case upon those who had first entered it. You will recollect that Mortimer Tregennis, in describing the episode of his last visit to his brother’s house, remarked that the doctor on entering the room fell into a chair? You had forgotten? Well I can answer for it that it was so. Now, you will remember also that Mrs. Porter, the housekeeper, told us that she herself fainted upon entering the room and had afterwards opened the window. In the second case—that of Mortimer Tregennis himself—you cannot have forgotten the horrible stuffiness of the room when we arrived, though the servant had thrown open the window. That servant, I found upon inquiry, was so ill that she had gone to her bed. You will admit, Watson, that these facts are very suggestive. In each case there is evidence of a poisonous atmosphere. In each case, also, there is combustion going on in the room—in the one case a fire, in the other a lamp. The fire was needed, but the lamp was lit—as a comparison of the oil consumed will show—long after it was broad daylight. Why? Surely because there is some connection between three things—the burning, the stuffy atmosphere, and, finally, the madness or death of those unfortunate people. That is clear, is it not?”

“It would appear so.”

“At least we may accept it as a working hypothesis. We will suppose, then, that something was burned in each case which produced an atmosphere causing strange toxic effects. Very good. In the first instance—that of the Tregennis family—this substance was placed in the fire. Now the window was shut, but the fire would naturally carry fumes to some extent up the chimney. Hence one would expect the effects of the poison to be less than in the second case, where there was less escape for the vapour. The result seems to indicate that it was so, since in the first case only the woman, who had presumably the more sensitive organism, was killed, the others exhibiting that temporary or permanent lunacy which is evidently the first effect of the drug. In the second case the result was complete. The facts, therefore, seem to bear out the theory of a poison which worked by combustion.

“With this train of reasoning in my head I naturally looked about in Mortimer Tregennis’s room to find some remains of this substance. The obvious place to look was the talc shelf or smoke-guard of the lamp. There, sure enough, I perceived a number of flaky ashes, and round the edges a fringe of brownish powder, which had not yet been consumed. Half of this I took, as you saw, and I placed it in an envelope.”

“Why half, Holmes?”

“It is not for me, my dear Watson, to stand in the way of the official police force. I leave them all the evidence which I found. The poison still remained upon the talc had they the wit to find it. Now, Watson, we will light our lamp; we will, however, take the precaution to open our window to avoid the premature decease of two deserving members of society, and you will seat yourself near that open window in an armchair unless, like a sensible man, you determine to have nothing to do with the affair. Oh, you will see it out, will you? I thought I knew my Watson. This chair I will place opposite yours, so that we may be the same distance from the poison and face to face. The door we will leave ajar. Each is now in a position to watch the other and to bring the experiment to an end should the symptoms seem alarming. Is that all clear? Well, then, I take our powder—or what remains of it—from the envelope, and I lay it above the burning lamp. So! Now, Watson, let us sit down and await developments.”

They were not long in coming. I had hardly settled in my chair before I was conscious of a thick, musky odour, subtle and nauseous. At the very first whiff of it my brain and my imagination were beyond all control. A thick, black cloud swirled before my eyes, and my mind told me that in this cloud, unseen as yet, but about to spring out upon my appalled senses, lurked all that was vaguely horrible, all that was monstrous and inconceivably wicked in the universe. Vague shapes swirled and swam amid the dark cloud-bank, each a menace and a warning of something coming, the advent of some unspeakable dweller upon the threshold, whose very shadow would blast my soul. A freezing horror took possession of me. I felt that my hair was rising, that my eyes were protruding, that my mouth was opened, and my tongue like leather. The turmoil within my brain was such that something must surely snap. I tried to scream and was vaguely aware of some hoarse croak which was my own voice, but distant and detached from myself. At the same moment, in some effort of escape, I broke through that cloud of despair and had a glimpse of Holmes’s face, white, rigid, and drawn with horror—the very look which I had seen upon the features of the dead. It was that vision which gave me an instant of sanity and of strength. I dashed from my chair, threw my arms round Holmes, and together we lurched through the door, and an instant afterwards had thrown ourselves down upon the grass plot and were lying side by side, conscious only of the glorious sunshine which was bursting its way through the hellish cloud of terror which had girt us in. Slowly it rose from our souls like the mists from a landscape until peace and reason had returned, and we were sitting upon the grass, wiping our clammy foreheads, and looking with apprehension at each other to mark the last traces of that terrific experience which we had undergone.

“Upon my word, Watson!” said Holmes at last with an unsteady voice, “I owe you both my thanks and an apology. It was an unjustifiable experiment even for one’s self, and doubly so for a friend. I am really very sorry.”

“You know,” I answered with some emotion, for I have never seen so much of Holmes’s heart before, “that it is my greatest joy and privilege to help you.”

He relapsed at once into the half-humorous, half-cynical vein which was his habitual attitude to those about him. “It would be superfluous to drive us mad, my dear Watson,” said he. “A candid observer would certainly declare that we were so already before we embarked upon so wild an experiment. I confess that I never imagined that the effect could be so sudden and so severe.” He dashed into the cottage, and, reappearing with the burning lamp held at full arm’s length, he threw it among a bank of brambles. “We must give the room a little time to clear. I take it, Watson, that you have no longer a shadow of a doubt as to how these tragedies were produced?”

“None whatever.”

“But the cause remains as obscure as before. Come into the arbour here and let us discuss it together. That villainous stuff seems still to linger round my throat. I think we must admit that all the evidence points to this man, Mortimer Tregennis, having been the criminal in the first tragedy, though he was the victim in the second one. We must remember, in the first place, that there is some story of a family quarrel, followed by a reconciliation. How bitter that quarrel may have been, or how hollow the reconciliation we cannot tell. When I think of Mortimer Tregennis, with the foxy face and the small shrewd, beady eyes behind the spectacles, he is not a man whom I should judge to be of a particularly forgiving disposition. Well, in the next place, you will remember that this idea of someone moving in the garden, which took our attention for a moment from the real cause of the tragedy, emanated from him. He had a motive in misleading us. Finally, if he did not throw the substance into the fire at the moment of leaving the room, who did do so? The affair happened immediately after his departure. Had anyone else come in, the family would certainly have risen from the table. Besides, in peaceful Cornwall, visitors did not arrive after ten o’clock at night. We may take it, then, that all the evidence points to Mortimer Tregennis as the culprit.”

“Then his own death was suicide!”

“Well, Watson, it is on the face of it a not impossible supposition. The man who had the guilt upon his soul of having brought such a fate upon his own family might well be driven by remorse to inflict it upon himself. There are, however, some cogent reasons against it. Fortunately, there is one man in England who knows all about it, and I have made arrangements by which we shall hear the facts this afternoon from his own lips. Ah! he is a little before his time. Perhaps you would kindly step this way, Dr. Leon Sterndale. We have been conducing a chemical experiment indoors which has left our little room hardly fit for the reception of so distinguished a visitor.”

I had heard the click of the garden gate, and now the majestic figure of the great African explorer appeared upon the path. He turned in some surprise towards the rustic arbour in which we sat.

“You sent for me, Mr. Holmes. I had your note about an hour ago, and I have come, though I really do not know why I should obey your summons.”

“Perhaps we can clear the point up before we separate,” said Holmes. “Meanwhile, I am much obliged to you for your courteous acquiescence. You will excuse this informal reception in the open air, but my friend Watson and I have nearly furnished an additional chapter to what the papers call the Cornish Horror, and we prefer a clear atmosphere for the present. Perhaps, since the matters which we have to discuss will affect you personally in a very intimate fashion, it is as well that we should talk where there can be no eavesdropping.”

The explorer took his cigar from his lips and gazed sternly at my companion.

“I am at a loss to know, sir,” he said, “what you can have to speak about which affects me personally in a very intimate fashion.”

“The killing of Mortimer Tregennis,” said Holmes.

For a moment I wished that I were armed. Sterndale’s fierce face turned to a dusky red, his eyes glared, and the knotted, passionate veins started out in his forehead, while he sprang forward with clenched hands towards my companion. Then he stopped, and with a violent effort he resumed a cold, rigid calmness, which was, perhaps, more suggestive of danger than his hot-headed outburst.

“I have lived so long among savages and beyond the law,” said he, “that I have got into the way of being a law to myself. You would do well, Mr. Holmes, not to forget it, for I have no desire to do you an injury.”

“Nor have I any desire to do you an injury, Dr. Sterndale. Surely the clearest proof of it is that, knowing what I know, I have sent for you and not for the police.”

Sterndale sat down with a gasp, overawed for, perhaps, the first time in his adventurous life. There was a calm assurance of power in Holmes’s manner which could not be withstood. Our visitor stammered for a moment, his great hands opening and shutting in his agitation.

“What do you mean?” he asked at last. “If this is bluff upon your part, Mr. Holmes, you have chosen a bad man for your experiment. Let us have no more beating about the bush. What do you mean?”

“I will tell you,” said Holmes, “and the reason why I tell you is that I hope frankness may beget frankness. What my next step may be will depend entirely upon the nature of your own defence.”

“My defence?”

“Yes, sir.”

“My defence against what?”

“Against the charge of killing Mortimer Tregennis.”

Sterndale mopped his forehead with his handkerchief. “Upon my word, you are getting on,” said he. “Do all your successes depend upon this prodigious power of bluff?”

“The bluff,” said Holmes sternly, “is upon your side, Dr. Leon Sterndale, and not upon mine. As a proof I will tell you some of the facts upon which my conclusions are based. Of your return from Plymouth, allowing much of your property to go on to Africa, I will say nothing save that it first informed me that you were one of the factors which had to be taken into account in reconstructing this drama——”

“I came back——”

“I have heard your reasons and regard them as unconvincing and inadequate. We will pass that. You came down here to ask me whom I suspected. I refused to answer you. You then went to the vicarage, waited outside it for some time, and finally returned to your cottage.”

“How do you know that?”

“I followed you.”

“I saw no one.”

“That is what you may expect to see when I follow you. You spent a restless night at your cottage, and you formed certain plans, which in the early morning you proceeded to put into execution. Leaving your door just as day was breaking, you filled your pocket with some reddish gravel that was lying heaped beside your gate.”

Sterndale gave a violent start and looked at Holmes in amazement.

“You then walked swiftly for the mile which separated you from the vicarage. You were wearing, I may remark, the same pair of ribbed tennis shoes which are at the present moment upon your feet. At the vicarage you passed through the orchard and the side hedge, coming out under the window of the lodger Tregennis. It was now daylight, but the household was not yet stirring. You drew some of the gravel from your pocket, and you threw it up at the window above you.”

Sterndale sprang to his feet.

“I believe that you are the devil himself!” he cried.

Holmes smiled at the compliment. “It took two, or possibly three, handfuls before the lodger came to the window. You beckoned him to come down. He dressed hurriedly and descended to his sitting-room. You entered by the window. There was an interview—a short one—during which you walked up and down the room. Then you passed out and closed the window, standing on the lawn outside smoking a cigar and watching what occurred. Finally, after the death of Tregennis, you withdrew as you had come. Now, Dr. Sterndale, how do you justify such conduct, and what were the motives for your actions? If you prevaricate or trifle with me, I give you my assurance that the matter will pass out of my hands forever.”

Our visitor’s face had turned ashen gray as he listened to the words of his accuser. Now he sat for some time in thought with his face sunk in his hands. Then with a sudden impulsive gesture he plucked a photograph from his breast-pocket and threw it on the rustic table before us.

“That is why I have done it,” said he.

It showed the bust and face of a very beautiful woman. Holmes stooped over it.

“Brenda Tregennis,” said he.

“Yes, Brenda Tregennis,” repeated our visitor. “For years I have loved her. For years she has loved me. There is the secret of that Cornish seclusion which people have marvelled at. It has brought me close to the one thing on earth that was dear to me. I could not marry her, for I have a wife who has left me for years and yet whom, by the deplorable laws of England, I could not divorce. For years Brenda waited. For years I waited. And this is what we have waited for.” A terrible sob shook his great frame, and he clutched his throat under his brindled beard. Then with an effort he mastered himself and spoke on:

“The vicar knew. He was in our confidence. He would tell you that she was an angel upon earth. That was why he telegraphed to me and I returned. What was my baggage or Africa to me when I learned that such a fate had come upon my darling? There you have the missing clue to my action, Mr. Holmes.”

“Proceed,” said my friend.

Dr. Sterndale drew from his pocket a paper packet and laid it upon the table. On the outside was written “Radix pedis diaboli” with a red poison label beneath it. He pushed it towards me. “I understand that you are a doctor, sir. Have you ever heard of this preparation?”

“Devil’s-foot root! No, I have never heard of it.”

“It is no reflection upon your professional knowledge,” said he, “for I believe that, save for one sample in a laboratory at Buda, there is no other specimen in Europe. It has not yet found its way either into the pharmacopoeia or into the literature of toxicology. The root is shaped like a foot, half human, half goatlike; hence the fanciful name given by a botanical missionary. It is used as an ordeal poison by the medicine-men in certain districts of West Africa and is kept as a secret among them. This particular specimen I obtained under very extraordinary circumstances in the Ubangi country.” He opened the paper as he spoke and disclosed a heap of reddish-brown, snuff-like powder.

“Well, sir?” asked Holmes sternly.

“I am about to tell you, Mr. Holmes, all that actually occurred, for you already know so much that it is clearly to my interest that you should know all. I have already explained the relationship in which I stood to the Tregennis family. For the sake of the sister I was friendly with the brothers. There was a family quarrel about money which estranged this man Mortimer, but it was supposed to be made up, and I afterwards met him as I did the others. He was a sly, subtle, scheming man, and several things arose which gave me a suspicion of him, but I had no cause for any positive quarrel.

“One day, only a couple of weeks ago, he came down to my cottage and I showed him some of my African curiosities. Among other things I exhibited this powder, and I told him of its strange properties, how it stimulates those brain centres which control the emotion of fear, and how either madness or death is the fate of the unhappy native who is subjected to the ordeal by the priest of his tribe. I told him also how powerless European science would be to detect it. How he took it I cannot say, for I never left the room, but there is no doubt that it was then, while I was opening cabinets and stooping to boxes, that he managed to abstract some of the devil’s-foot root. I well remember how he plied me with questions as to the amount and the time that was needed for its effect, but I little dreamed that he could have a personal reason for asking.

“I thought no more of the matter until the vicar’s telegram reached me at Plymouth. This villain had thought that I would be at sea before the news could reach me, and that I should be lost for years in Africa. But I returned at once. Of course, I could not listen to the details without feeling assured that my poison had been used. I came round to see you on the chance that some other explanation had suggested itself to you. But there could be none. I was convinced that Mortimer Tregennis was the murderer; that for the sake of money, and with the idea, perhaps, that if the other members of his family were all insane he would be the sole guardian of their joint property, he had used the devil’s-foot powder upon them, driven two of them out of their senses, and killed his sister Brenda, the one human being whom I have ever loved or who has ever loved me. There was his crime; what was to be his punishment?

“Should I appeal to the law? Where were my proofs? I knew that the facts were true, but could I help to make a jury of countrymen believe so fantastic a story? I might or I might not. But I could not afford to fail. My soul cried out for revenge. I have said to you once before, Mr. Holmes, that I have spent much of my life outside the law, and that I have come at last to be a law to myself. So it was even now. I determined that the fate which he had given to others should be shared by himself. Either that or I would do justice upon him with my own hand. In all England there can be no man who sets less value upon his own life than I do at the present moment.

“Now I have told you all. You have yourself supplied the rest. I did, as you say, after a restless night, set off early from my cottage. I foresaw the difficulty of arousing him, so I gathered some gravel from the pile which you have mentioned, and I used it to throw up to his window. He came down and admitted me through the window of the sitting-room. I laid his offence before him. I told him that I had come both as judge and executioner. The wretch sank into a chair, paralyzed at the sight of my revolver. I lit the lamp, put the powder above it, and stood outside the window, ready to carry out my threat to shoot him should he try to leave the room. In five minutes he died. My God! how he died! But my heart was flint, for he endured nothing which my innocent darling had not felt before him. There is my story, Mr. Holmes. Perhaps, if you loved a woman, you would have done as much yourself. At any rate, I am in your hands. You can take what steps you like. As I have already said, there is no man living who can fear death less than I do.”

Holmes sat for some little time in silence.

“What were your plans?” he asked at last.

“I had intended to bury myself in central Africa. My work there is but half finished.”

“Go and do the other half,” said Holmes. “I, at least, am not prepared to prevent you.”

Dr. Sterndale raised his giant figure, bowed gravely, and walked from the arbour. Holmes lit his pipe and handed me his pouch.

“Some fumes which are not poisonous would be a welcome change,” said he. “I think you must agree, Watson, that it is not a case in which we are called upon to interfere. Our investigation has been independent, and our action shall be so also. You would not denounce the man?”

“Certainly not,” I answered.

“I have never loved, Watson, but if I did and if the woman I loved had met such an end, I might act even as our lawless lion-hunter has done. Who knows? Well, Watson, I will not offend your intelligence by explaining what is obvious. The gravel upon the window-sill was, of course, the starting-point of my research. It was unlike anything in the vicarage garden. Only when my attention had been drawn to Dr. Sterndale and his cottage did I find its counterpart. The lamp shining in broad daylight and the remains of powder upon the shield were successive links in a fairly obvious chain. And now, my dear Watson, I think we may dismiss the matter from our mind and go back with a clear conscience to the study of those Chaldean roots which are surely to be traced in the Cornish branch of the great Celtic speech.”

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

His Last Bow (from: The Adventure of the Devil’s Foot)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan

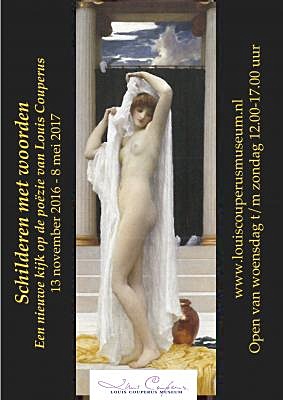

Nieuwe tentoonstelling Schilderen met woorden. Een nieuwe kijk op de poëzie van Louis Couperus. 13 november 2016 – 8 mei 2017 in het Louis Couperus Museum.

Nieuwe tentoonstelling Schilderen met woorden. Een nieuwe kijk op de poëzie van Louis Couperus. 13 november 2016 – 8 mei 2017 in het Louis Couperus Museum.

Gedurende een groot deel van zijn leven (om precies te zijn 25 jaar) heeft Louis Couperus poëzie geschreven. Tot nu toe is er te weinig aandacht geschonken aan dit onderwerp.

Deze winter visualiseert het Louis Couperus Museum de dichtkunst van de Haagse schrijver door middel van afbeeldingen en beeldhouwwerk waardoor de schrijver was geïnspireerd.

Tentoonstelling

Aan de wanden worden representatieve gedichten of citaten daaruit groot weer gegeven, op textiel afgedrukt. Bij elk fragment komt een afbeelding te hangen die inhoudelijk in verband staat met het betreffende gedicht. Reproducties van schilderijen – in een enkel geval zelfs een beeldhouwwerk – hebben Couperus soms regelrecht tot voorbeeld gediend. Ook de doorwerking van zijn poëzie in zijn proza komt aan bod. Op de televisiemonitor is een voordracht van zijn dichtkunst door acteur Joop Keesmaat te zien en te horen.

De expositie is gecentreerd rond 5 thema’s uit Couperus’ poëzie. Allereerst de figuur van Petrarca die hem de Laura-cyclus in gaf. Ten tweede de salon-schilderkunst uit de negentiende eeuw en daarmee samenhangend gedichten waarin Couperus bijna letterlijk ‘met woorden schildert’. Vervolgens het beeld Alba van de Friese beeldhouwer Pier Pander, dat Couperus in het gelijknamige sonnet bezong. Dan de wereld van de Arthurlegenden die hem zo boeide, en de door Italië geïnspireerde gedichten. De ‘aardse Couperus’ (Arjan Peters) komt in de ‘sonnettenroman’ Endymion aan bod. Hierin vereenzelvigt Couperus zich met een volksjongen die in de klassieke metropool Alexandrië allerlei avonturen beleeft. Dit wordt op eigentijdse wijze gevisualiseerd door een stripverhaal van de hand van Mees Arnzt, een student van de Koninklijke Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten.

Verantwoording

De tentoonstelling wordt ingericht door gastconservator Frans van der Linden, medewerker van het Louis Couperus Museum, winnaar van de Couperuspenning en samensteller van het boekje O gouden, stralenshelle fantazie! Bloemlezing uit de poëzie van Louis Couperus (in de Prominentreeks van Uitgeverij Tiem, 2015).

De expositie wordt mede mogelijk gemaakt dankzij een bijdrage van het Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds.

schilderen met woorden.

een nieuwe kijk op de poëzie van Couperus

13 november 2016 – 8 mei 2017

Louis Couperus Museum

Javastraat 17

2585 AB Den Haag

070-3640653

info@louiscouperusmuseum.nl

Openingstijden

Woensdag t/m zondag 12.00-17.00 uur

Voor groepen ook op afspraak

Het gehele jaar door geopend, met uitzondering van 1ste en 2de Kerstdag en Nieuwjaarsdag

Toegankelijk voor gehandicapten

# Meer informatie op website van het Couperus Museum

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Literary Events, Louis Couperus, Museum of Literary Treasures

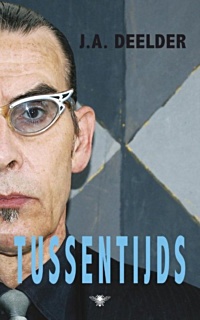

De Kunsthal Rotterdam presenteert het Locomotrutfantje, Moeder de Gans, Spartapiet, Cubaanse vlieg, Doorzager, Blauwwerker en meer beelden van Jules Deelder. Deelder, beter bekend als dichter en nachtburgemeester van Rotterdam, laat de poëzie van zijn verbeelding spreken. Zoals een echte dichter betaamt geeft hij zijn creaties de meest toepasselijke namen. In de tentoonstelling zijn elf unieke ‘Beelder’ te zien, gemaakt van kleurrijk plastic.

Sinds anderhalf jaar verzamelt J.A. Deelder pennen, cocktailstampertjes, injectiespuiten, pijpjes, rietjes, lepeltjes, tandenborstels, speelgoed en lensdopjes, om ze daarna op kleur te sorteren. Met lijm verwerkt Deelder al deze materialen tot driedimensionale objecten, waarmee hij een nieuwe dimensie aan zijn rijke oeuvre van poëzie en performances toevoegt. Hij zegt daar zelf over:

Je zit gewoon een beetje te klootzakke, en op een gegeven moment wordt het wat!

Jules Deelder

Ruimteschepen: Als Deelder’s dochter Ari in 2015 een film maakt over Willem Koopman alias Willem de wielrenner, vindt zij haar vader bereid een aantal ruimteschepen te maken zoals Willem altijd deed in de kroegen van Rotterdam. Koopman, een ex-wielrenner en voormalig zwerver met een bovennatuurlijke missie, zag Rotterdam als een ruimteschip dat elk moment uit het heelal geschoten kon worden. Deelder daarentegen ziet zijn creaties niet opstijgen tot in de verre uithoeken van het heelal, maar juist landen in de Kunsthal.

Over Jules Deelder: J.A. Deelder wordt in 1944 geboren als zoon van een Rotterdamse handelaar in vleeswaren. Sinds de vroege jaren zestig heeft Deelder nationale bekendheid als jazzconnaisseur, schrijver, dichter, performer en bovenal Rotterdammer. Zijn uitgesproken voorkeur voor zwarte kleding, vlinderbrillen, Sparta, Citroën en wielrennen maakt hem tot een graag geziene gast in tv- en radioprogramma’s.

Over Jules Deelder: J.A. Deelder wordt in 1944 geboren als zoon van een Rotterdamse handelaar in vleeswaren. Sinds de vroege jaren zestig heeft Deelder nationale bekendheid als jazzconnaisseur, schrijver, dichter, performer en bovenal Rotterdammer. Zijn uitgesproken voorkeur voor zwarte kleding, vlinderbrillen, Sparta, Citroën en wielrennen maakt hem tot een graag geziene gast in tv- en radioprogramma’s.

De Kunsthal Rotterdam is een van de toonaangevende culturele instellingen in Nederland, gelegen in het Museumpark in Rotterdam. Ontworpen door de beroemde architect Rem Koolhaas in 1992, biedt de Kunsthal zeven verschillende tentoonstellingsruimtes. Jaarlijks presenteert de Kunsthal een gevarieerd programma van circa 25 tentoonstellingen. Omdat er altijd meerdere tentoonstellingen tegelijk te bezichtigen zijn, biedt de Kunsthal een avontuurlijke reis door verschillende werelddelen en kunststromingen. Cultuur voor een breed publiek, van moderne meesters en hedendaagse kunst tot vergeten culturen, fotografie, mode en design. Bij de tentoonstellingen wordt een uitgebreid activiteitenprogramma georganiseerd.

Kunsthal Rotterdam

17 december 2016 tot 19 maart 2017

Dinsdag t/m zaterdag 10 — 17 uur

Zondag 11 — 17 uur

Museumpark

Westzeedijk 341

3015 AA Rotterdam

# Meer informatie op website Kunsthal Rotterdam

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Exhibition Archive, Jules Deelder

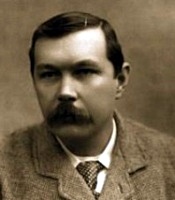

The Adventure of The Sussex Vampire

The Adventure of The Sussex Vampire

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Holmes had read carefully a note which the last post had brought him. Then, with the dry chuckle which was his nearest approach to a laugh, he tossed it over to me.

“For a mixture of the modern and the medieval, of the practical and of the wildly fanciful, I think this is surely the limit,” said he. “What do you make of it, Watson?”

I read as follows:

46, OLD JEWRY,

Nov. 19th.

Re Vampires

SIR:

Our client, Mr. Robert Ferguson, of Ferguson and

Muirhead, tea brokers, of Mincing Lane, has made some

inquiry from us in a communication of even date concerning

vampires. As our firm specializes entirely upon the as

sessment of machinery the matter hardly comes within our

purview, and we have therefore recommended Mr. Fergu

son to call upon you and lay the matter before you. We

have not forgotten your successful action in the case of

Matilda Briggs.

We are, sir,

Faithfully yours,

MORRISON, MORRISON, AND DODD.

per E. J. C.

“Matilda Briggs was not the name of a young woman, Watson,” said Holmes in a reminiscent voice. “It was a ship which is associated with the giant rat of Sumatra, a story for which the world is not yet prepared. But what do we know about vampires? Does it come within our purview either? Anything is better than stagnation, but really we seem to have been switched on to a Grimms’ fairy tale. Make a long arm, Watson, and see what V has to say.”

I leaned back and took down the great index volume to which he referred. Holmes balanced it on his knee, and his eyes moved slowly and lovingly over the record of old cases, mixed with the accumulated information of a lifetime.

“Voyage of the Gloria Scott,” he read. “That was a bad business. I have some recollection that you made a record of it, Watson, though I was unable to congratulate you upon the result. Victor Lynch, the forger. Venomous lizard or gila. Remarkable case, that! Vittoria, the circus belle. Vanderbilt and the Yeggman. Vipers. Vigor, the Hammersmith wonder. Hullo! Hullo! Good old index. You can’t beat it. Listen to this, Watson. Vampirism in Hungary. And again, Vampires in Transylvania.” He turned over the pages with eagerness, but after a short intent perusal he threw down the great book with a snarl of disappointment.

“Rubbish, Watson, rubbish! What have we to do with walking corpses who can only be held in their grave by stakes driven through their hearts? It’s pure lunacy.”

“But surely,” said I, “the vampire was not necessarily a dead man? A living person might have the habit. I have read, for example, of the old sucking the blood of the young in order to retain their youth.”

“You are right, Watson. It mentions the legend in one of these references. But are we to give serious attention to such things? This agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain. The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply. I fear that we cannot take Mr. Robert Ferguson very seriously. Possibly this note may be from him and may throw some light upon what is worrying him.”

He took up a second letter which had lain unnoticed upon the table while he had been absorbed with the first. This he began to read with a smile of amusement upon his face which gradually faded away into an expression of intense interest and concentration. When he had finished he sat for some little time lost in thought with the letter dangling from his fingers. Finally, with a start, he aroused himself from his reverie.

“Cheeseman’s, Lamberley. Where is Lamberley, Watson?”

“lt is in Sussex, South of Horsham.”

“Not very far, eh? And Cheeseman’s?”

“I know that country, Holmes. It is full of old houses which are named after the men who built them centuries ago. You get Odley’s and Harvey’s and Carriton’s — the folk are forgotten but their names live in their houses.”

“Precisely,” said Holmes coldly. It was one of the peculiarities of his proud, self-contained nature that though he docketed any fresh information very quietly and accurately in his brain, he seldom made any acknowledgment to the giver. “I rather fancy we shall know a good deal more about Cheeseman’s, Lamberley, before we are through. The letter is, as I had hoped, from Robert Ferguson. By the way, he claims acquaintance with you.”

“With me!”

“You had better read it.”

He handed the letter across. It was headed with the address quoted.

DEAR MR HOLMES [it said]:

I have been recommended to you by my lawyers, but

indeed the matter is so extraordinarily delicate that it is most

difficult to discuss. It concerns a friend for whom I am

acting. This gentleman married some five years ago a Peruvian

lady the daughter of a Peruvian merchant, whom he had

met in connection with the importation of nitrates. The lady

was very beautiful, but the fact of her foreign birth and of

her alien religion always caused a separation of interests and

of feelings between husband and wife, so that after a time

his love may have cooled towards her and he may have

come to regard their union as a mistake. He felt there were

sides of her character which he could never explore or

understand. This was the more painful as she was as loving

a wife as a man could have — to all appearance absolutely

devoted.

Now for the point which I will make more plain when we

meet. Indeed, this note is merely to give you a general idea

of the situation and to ascertain whether you would care to

interest yourself in the matter. The lady began to show

some curious traits quite alien to her ordinarily sweet and

gentle disposition. The gentleman had been married twice

and he had one son by the first wife. This boy was now

fifteen, a very charming and affectionate youth, though

unhappily injured through an accident in childhood. Twice

the wife was caught in the act of assaulting this poor lad in

the most unprovoked way. Once she struck him with a stick

and left a great weal on his arm.

This was a small matter, however, compared with her

conduct to her own child, a dear boy just under one year of

age. On one occasion about a month ago this child had

been left by its nurse for a few minutes. A loud cry from the

baby, as of pain, called the nurse back. As she ran into the

room she saw her employer, the lady, leaning over the baby

and apparently biting his neck. There was a small wound in

the neck from which a stream of blood had escaped. The

nurse was so horrified that she wished to call the husband,

but the lady implored her not to do so and actually gave her

five pounds as a price for her silence. No explanation was

ever given, and for the moment the matter was passed over.

It left, however, a terrible impression upon the nurse’s

mind, and from that time she began to watch her mistress

closely and to keep a closer guard upon the baby, whom she

tenderly loved. It seemed to her that even as she watched

the mother, so the mother watched her, and that every time

she was compelled to leave the baby alone the mother was

waiting to get at it. Day and night the nurse covered the

child, and day and night the silent, watchful mother seemed

to be lying in wait as a wolf waits for a lamb. It must read

most incredible to you, and yet I beg you to take it seri

ously, for a child’s life and a man’s sanity may depend

upon it.

At last there came one dreadful day when the facts could

no longer be concealed from the husband. The nurse’s nerve

had given way; she could stand the strain no longer, and

she made a clean breast of it all to the man. To him it

seemed as wild a tale as it may now seem to you.He knew

his wife to be a loving wife, and, save for the assaults

upon her stepson, a loving mother. Why, then, should

she wound her own dear little baby? He told the nurse that

she was dreaming, that her suspicions were those of a

lunatic, and that such libels upon her mistress were not to be

tolerated. While they were talking a sudden cry of pain was

heard. Nurse and master rushed together to the nursery.

Imagine his feelings, Mr. Holmes, as he saw his wife rise

from a kneeling position beside the cot and saw blood upon

the child’s exposed neck and upon the sheet. With a cry of

horror, he turned his wife’s face to the light and saw blood

all round her lips. It was she — she beyond all question –

who had drunk the poor baby’s blood.

So the matter stands. She is now confined to her room.

There has been no explanation. The husband is half de

mented. He knows, and I know, little of vampirism beyond

the name. We had thought it was some wild tale of foreign

parts. And yet here in the very heart of the English Sussex –

well, all this can be discussed with you in the morning. Will

you see me? Will you use your great powers in aiding a

distracted man? If so, kindly wire to Ferguson, Cheeseman’s,

Lamberley, and I will be at your rooms by ten o’clock.

Yours faithfully,

ROBERT FERGUSON

P. S. I believe your friend Watson played Rugby for

Blackheath when I was three-quarter for Richmond. It is the

only personal introduction which I can give.

“Of course I remembered him,” said I as I laid down the letter. “Big Bob Ferguson, the finest three-quarter Richmond ever had. He was always a good-natured chap. It’s like him to be so concerned over a friend’s case.”

Holmes looked at me thoughtfully and shook his head.

“I never get your limits, Watson,” said he. “There are unexplored possibilities about you. Take a wire down, like a good fellow. ‘Will examine your case with pleasure.’ “

“Your case!”

“We must not let him think that this agency is a home for the weak-minded. Of course it is his case. Send him that wire and let the matter rest till morning.”

Promptly at ten o’clock next morning Ferguson strode into our room. I had remembered him as a long, slab-sided man with loose limbs and a fine turn of speed which had carried him round many an opposing back. There is surely nothing in life more painful than to meet the wreck of a fine athlete whom one has known in his prime. His great frame had fallen in, his flaxen hair was scanty, and his shoulders were bowed. I fear that I roused corresponding emotions in him.

“Hullo, Watson,” said he, and his voice was still deep and hearty. “You don’t look quite the man you did when I threw you over the ropes into the crowd at the Old Deer Park. I expect I have changed a bit also. But it’s this last day or two that has aged me. I see by your telegram, Mr. Holmes, that it is no use my pretending to be anyone’s deputy.” .

“It is simpler to deal direct,” said Holmes.

“Of course it is. But you can imagine how difficult it is when you are speaking of the one woman whom you are bound to protect and help. What can I do? How am I to go to the police with such a story? And yet the kiddies have got to be protected. Is it madness, Mr. Holmes? Is it something in the blood? Have you any similar case in your experience? For God’s sake, give me some advice, for I am at my wit’s end.”

“Very naturally, Mr. Ferguson. Now sit here and pull yourself together and give me a few clear answers. I can assure you that I am very far from being at my wit’s end, and that I am confident we shall find some solution. First of all, tell me what steps you have taken. Is your wife still near the children?”

“We had a dreadful scene. She is a most loving woman, Mr. Holmes. If ever a woman loved a man with all her heart and soul, she loves me. She was cut to the heart that I should have discovered this horrible, this incredible, secret. She would not even speak. She gave no answer to my reproaches, save to gaze at me with a sort of wild, despairing look in her eyes. Then she rushed to her room and locked herself in. Since then she has refused to see me. She has a maid who was with her before her marriage, Dolores by name — a friend rather than a servant. She takes her food to her.”

“Then the child is in no immediate danger?”

“Mrs. Mason, the nurse, has sworn that she will not leave it night or day. I can absolutely trust her. I am more uneasy about poor little Jack, for, as I told you in my note, he has twice been assaulted by her.”

“But never wounded?”

“No, she struck him savagely. It is the more terrible as he is a poor little inoffensive cripple.” Ferguson’s gaunt features softened as he spoke of his boy. “You would think that the dear lad’s condition would soften anyone’s heart. A fall in childhood and a twisted spine, Mr. Holmes. But the dearest, most loving heart within.”

Holmes had picked up the letter of yesterday and was reading it over. “What other inmates are there in your house, Mr. Ferguson?”

“Two servants who have not been long with us. One stablehand, Michael, who sleeps in the house. My wife, myself, my boy Jack, baby, Dolores, and Mrs. Mason. That is all.”

“I gather that you did not know your wife well at the time of your marriage?”

“I had only known her a few weeks.”

“How long had this maid Dolores been with her?”

“Some years.”

“Then your wife’s character would really be better known by Dolores than by you?”

“Yes, you may say so.”

Holmes made a note.

“I fancy,” said he, “that I may be of more use at Lamberley than here. It is eminently a case for personal investigation. If the lady remains in her room, our presence could not annoy or inconvenience her. Of course, we would stay at the inn.”

Ferguson gave a gesture of relief.

“It is what I hoped, Mr. Holmes. There is an excellent train at two from Victoria if you could come.”

“Of course we could come. There is a lull at present. I can give you my undivided energies. Watson, of course, comes with us. But there are one or two points upon which I wish to be very sure before I start. This unhappy lady, as I understand it, has appeared to assault both the children, her own baby and your little son?”

“That is so.”

“But the assaults take different forms, do they not? She has beaten your son.”

“Once with a stick and once very savagely with her hands.”

“Did she give no explanation why she struck him?”

“None save that she hated him. Again and again she said so.”

“Well, that is not unknown among stepmothers. A posthumous jealousy, we will say. Is the lady jealous by nature?”

“Yes, she is very jealous — jealous with all the strength of her fiery tropical love.”

“But the boy — he is fifteen, I understand, and probably very developed in mind, since his body has been circumscribed in action. Did he give you no explanation of these assaults?”

“No, he declared there was no reason.”

“Were they good friends at other times?”

“No, there was never any love between them.”

“Yet you say he is affectionate?”

“Never in the world could there be so devoted a son. My life is his life. He is absorbed in what I say or do.”

Once again Holmes made a note. For some time he sat lost in thought.

“No doubt you and the boy were great comrades before this second marriage. You were thrown very close together, were you not?”

“Very much so.”

“And the boy, having so affectionate a nature, was devoted, no doubt, to the memory of his mother?”

“Most devoted.”

“He would certainly seem to be a most interesting lad. There is one other point about these assaults. Were the strange attacks upon the baby and the assaults upon yow son at the same period?”

“In the first case it was so. It was as if some frenzy had seized her, and she had vented her rage upon both. In the second case it was only Jack who suffered. Mrs. Mason had no complaint to make about the baby.”

“That certainly complicates matters.”

“I don’t quite follow you, Mr. Holmes.”

“Possibly not. One forms provisional theories and waits for time or fuller knowledge to explode them. A bad habit, Mr. Ferguson, but human nature is weak. I fear that your old friend here has given an exaggerated view of my scientific methods. However, I will only say at the present stage that your problem does not appear to me to be insoluble, and that you may expect to find us at Victoria at two o’clock.”