Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

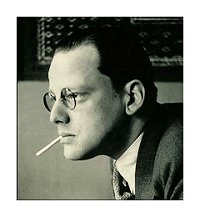

Menno ter Braak

1902-1940

De gedachte

Het dorp hing tussen de brandende korenvelden als een dwaas en machteloos punt; een eigengereide en onverdedigbare uitzondering op de regel, dat dit land gebukt ging onder het graan. Het sloeg een uitgezakt gat in de algemeenheid, die in deze streken tarwe heette. En ook had dit gat abnormaliteiten, die weer braken in het dogma, dat een gat een onafwendbare noodzakelijkheid is. Bultige straten liepen stompzinnig dood in doorgroefde landwegen, die onder het koren te niet gingen. Vierkante huizen, ordeloos langs de dorpszoom gestrooid, verkondigden de leer der vervloeiing; want het dorp weigerde plotseling en zonder overgang te wijken voor het land, waarop het een uitzondering was.

Dit dorp was een onuitgewerkte gedachte. Zoals het zich stelde als een niet geheel doorpeinsd punt, behoefde het een nadere verklaring, waarom het juist dáár neergedoken zat. Hierover had het door de eeuwen heen stof tot denken gehad, maar het probleem was gebleven. Dagelijks spiegelde het zich in een zonderling water, dat restte van een gekanaliseerde beek, die tot zuiverder lijn ingekeerd was. Alleen dit irreële en riekende water was in de waan gebleven, dat het dorp in eindeloze spiegeling tenslotte een oplossing zou vinden; daarom was het trouw geweest en niet meegetrokken naar het land, dat van de aanvang der geheelheid was en geen verklaring van node had. Ieder jaar schrompelde het een el ineen, moeizaam, slijmige vezels achterlatend.

Maar het dorp kon zich nog steeds spiegelen en zich afvragen, waarom het in deze windstreken moest geschapen zijn en een willoze en verborgen cirkel snijden in de golvende vlakte.

Bevreemdend is het, dat dit dorp, nog slechts gedeeltelijk gedacht en begrepen en steeds gedwongen zich op te lossen, een bevolking had zonder buitengewone denkkracht. Velen van deze mensen waren zich zelf niet bewust, dat zij van een ander ras waren dan de stugge boeren, die als gewillige knechten het tarweland dienden met hun dorre lichamen. Dezen behoefden te denken noch te vragen, want zonder hen waren de velden onredelijk geweest; doch een andere taak hadden de dorpelingen. Zij scholen saâm in een plaats, die hun dienst niet vergde als een noodzaak. Hun dorp was tussen het land, waaraan géén twijfelt, een onverstaanbare gril. Maar zij beseften het niet. De bakkers werden er grauw en wezenloos onder hun arbeid, de slagers glansden er van vet, een dominee sprak er iedere zondagmorgen gewijde woorden, als waren er geen grote vraagstukken. Allen scholen binnen deze groteske beperking van de ongerepte horizon en dromden bijeen zonder protest, zonder klacht, zonder twijfel.

Toch waren er tekenen, uitwijzend, dat de onvoldragen gedachte, die het dorp was, steeds naar vervulling hunkerde.

Er is geen gedachte, die zich tevreden stelt met lege algemeenheid; elk zoekt vleeswording, begerend tot de mensen te komen…

Zo ook stootte dit dorp iedere halve eeuw een zonderling uit. Hij leefde plotseling op en stierf even onverwacht. Eerst na zijn dood begreep men, dat hij weer voor allen de zware last der gedachte op zich had genomen. Dan werden legenden over zijn rondwandeling op aarde gehoord; in de jeugd der tijden slopen zij als gefluisterde sproken rond door de woningen en later schreven de couranten over hem onder opzienbarende hoofden. Want omdat hij de moed had te denken, was hij vaak eenzelvig, afstotend, dwaas voor de menigte, die het leven doordribbelt.

Deze zonderlingen werden in verschillende standen geboren. Voor de eerste, die de historie boekte, zei men, dat hij als flagellant boetend voor bedreven zonden rondtrok door Europa; een tweede stierf op een ketterbrandstapel; een derde was verdwenen in de stroom der grote omwenteling. De één stamde uit een oud, lang bekend geslacht, de ander uit een krot, neerhurkend aan de toren.

Maar allen hadden als kinderen het redeloze dorp gekend en zich eerst, in vage aandrift van het instinct, afgevraagd, wat het daar deed temidden van de aanstromende tarwe, zonder uitweg. Zij waren mannen geworden, rijker aan gedachten dan de overige dorpelingen. Als eenzamen hadden zij gestaan, waar anderen grepen, wat aan deze wereld begeerlijk schijnt. In de nachten stortte de hemel over hun wanhopige hoofden in. Zij duizelden voor de sterren.

Het kruis van de gedachte hadden zij opgenomen. Zij vluchtten weg voor de beelden, die zij schiepen. En vergingen. In het dorp bleef de geleidelijkheid; de beek alleen werd in een plotselinge vlaag van energie gekanaliseerd en slechts het riekende water bleef, een steeds schrompelende spiegel.

De laatste, van wie men tot op deze dagen getuigd heeft, dat hij de raadselachtige roeping volgde, was een wijsgeer. Van hem staan geen grote dingen geschreven. In een aanmatigend en zeer troosteloos huis, zoals een vorige eeuw ze in scharen deed verrijzen, sleet hij zijn leven. Hij droeg een naam, die hij van zijn vader met het huis had overgenomen en was ambteloos burger. In zijn tuin bloeiden steeds dezelfde bloemen in krullende en kronkelende perkjes, wisselend met de jaargetijden. Een oude tuinman verzorgde ze, zoals een oude vrouw het huis en zijn eigenaar. De wijsgeer zag hen zelden en sprak met hen alleen over het loon. Met het dorp onderhield hij geen gemeenschap. Hij was geen lid van verenigingen, die liefdadigheid of godsdienst beoefenden en dus meende men hem met recht als gierig en afkerig van goddelijke zaken te kunnen beschouwen. Immers slechts een enkele begon te doorzien, dat hij tot de groten behoorde, die voor het dorp lijden moesten en de last der gedachte dragen. Zij spraken er aarzelend over, maar anderen lachten en wierpen het vermoeden neer door hun lach. Zo was het gegaan met allen…

Aan dit bestaan knoopten zich geen romantische jeugdherinneringen, geen lieve verhalen van een verkwijnde jonge vrouw of verklonken muziek. Wat zelfs een oud en vermoeid gezicht aan de jeugd verbindt, was voor deze mens een te rijke gave. Geen had hem anders gekend dan mager, gebogen en in zichzelf besloten. Evenmin kende men van hem een vreemd gerucht. Altijd had hij verborgen geleefd zonder zich te verbergen. Hij zwierf van zijn boeken naar het korenland en het krimpende water, maar zijn kleren waren niet ongewoon; dit gaf derhalve geen aanstoot.

Van zijn lijden wist men niet.

En ook deze is de kruisdood gestorven.

Eens toen de nacht gevorderd was, ging hij ten laatste male door de ontvolkte straat, tot waar de tarwe het dorp naderde. Bezijden lag het zonderlinge water achter de duisternis. En ten laatste male heeft hij het gevraagd, de gepijnigde, aan allen, die horen wilden, dat is géén. Waarom in de algemeenheid de uitzondering moet zijn, waarom aan de redeloosheid de Rede moet gekend worden, waarom de mens de meest verhevene en de meest beperkte is.

Noch het land, noch het dorp antwoordden… En hij keerde. Voor hem geen boetende gesel, geen brandstapel, geen dood op de barricaden. Hij was slechts een ambteloos burger, die het kruis van de gedachte op zich had genomen; daarom slikte hij vergift, bij een apotheker bemachtigd.

De hemel brak. Een ster werd tot een lichtfontein. En hij verging.

Na hem zullen anderen vergaan, omdat zij denken.

Menno ter Braak

17 mei 1924

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Menno ter Braak

Arthur Rimbaud

(1854-1891)

Scènes

L’ancienne Comédie poursuit ses accords et divise ses Idylles :

Des boulevards de tréteaux.

Un long pier en bois d’un bout à l’autre d’un champ rocailleux où la foule barbare évolue sous les arbres dépouillés.

Dans des corridors de gaze noire suivant le pas des promeneurs aux lanternes et aux feuilles.

Des oiseaux des mystères s’abattent sur un ponton de maçonnerie mû par l’archipel couvert des embarcations des spectateurs.

Des scènes lyriques accompagnées de flûte et de tambour s’inclinent dans des réduits ménagés sous les plafonds, autour des salons de clubs modernes ou des salles de l’Orient ancien.

La féerie manœuvre au sommet d’un amphithéâtre couronné par les taillis, — Ou s’agite et module pour les Béotiens, dans l’ombre des futaies mouvantes sur l’arête des cultures.

L’opéra-comique se divise sur une scène à l’arête d’intersection de dix cloisons dressées de la galerie aux feux.

Arthur Rimbaud poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive Q-R, Arthur Rimbaud, Rimbaud, Arthur

Hans Christian Andersen

(1805—1875)

The nightingale

In China, you know, the emperor is a Chinese, and all those about him are Chinamen also. The story I am going t tell you happened a great many years ago, so it is well to hear it now before it is forgotten. The emperor’s palac was the most beautiful in the world. It was built entirely of porcelain, and very costly, but so delicate and brittle tha whoever touched it was obliged to be careful. In the garden could be seen the most singular flowers, with prett silver bells tied to them, which tinkled so that every one who passed could not help noticing the flowers.

Indeed everything in the emperor’s garden was remarkable, and it extended so far that the gardener himself did not kno where it ended. Those who travelled beyond its limits knew that there was a noble forest, with lofty trees, slopin down to the deep blue sea, and the great ships sailed under the shadow of its branches. In one of these trees live a nightingale, who sang so beautifully that even the poor fishermen, who had so many other things to do, woul stop and listen. Sometimes, when they went at night to spread their nets, they would hear her sing, and say, “Oh, i not that beautiful?” But when they returned to their fishing, they forgot the bird until the next night. Then they woul hear it again, and exclaim “Oh, how beautiful is the nightingale’s song!

Travellers from every country in the world came to the city of the emperor, which they admired very much, as well as the palace and gardens; but when they heard the nightingale, they all declared it to be the best of all.

And the travellers, on their return home, related what they had seen; and learned men wrote books, containing descriptions of the town, the palace, and the gardens; but they did not forget the nightingale, which was really the greatest wonder. And those who could write poetry composed beautiful verses about the nightingale, who lived in a forest near the deep sea.

The books travelled all over the world, and some of them came into the hands of the emperor; and he sat in his golden chair, and, as he read, he nodded his approval every moment, for it pleased him to find such a beautiful description of his city, his palace, and his gardens. But when he came to the words, “the nightingale is the most beautiful of all,” he exclaimed:

“What is this? I know nothing of any nightingale. Is there such a bird in my empire? and even in my garden? I have never heard of it. Something, it appears, may be learnt from books.”

Then he called one of his lords-in-waiting, who was so high-bred, that when any in an inferior rank to himself spoke to him, or asked him a question, he would answer, “Pooh,” which means nothing.

“There is a very wonderful bird mentioned here, called a nightingale,” said the emperor; “they say it is the best thing in my large kingdom. Why have I not been told of it?”

“I have never heard the name,” replied the cavalier; “she has not been presented at court.”

“It is my pleasure that she shall appear this evening.” said the emperor; “the whole world knows what I possess better than I do myself.”

“I have never heard of her,” said the cavalier; “yet I will endeavor to find her.”

But where was the nightingale to be found? The nobleman went up stairs and down, through halls and passages; yet none of those whom he met had heard of the bird. So he returned to the emperor, and said that it must be a fable, invented by those who had written the book. “Your imperial majesty,” said he, “cannot believe everything contained in books; sometimes they are only fiction, or what is called the black art.”

“But the book in which I have read this account,” said the emperor, “was sent to me by the great and mighty emperor of Japan, and therefore it cannot contain a falsehood. I will hear the nightingale, she must be here this evening; she has my highest favor; and if she does not come, the whole court shall be trampled upon after supper is ended.”

“Tsing-pe!” cried the lord-in-waiting, and again he ran up and down stairs, through all the halls and corridors; and half the court ran with him, for they did not like the idea of being trampled upon. There was a great inquiry about this wonderful nightingale, whom all the world knew, but who was unknown to the court.

At last they met with a poor little girl in the kitchen, who said, “Oh, yes, I know the nightingale quite well; indeed, she can sing. Every evening I have permission to take home to my poor sick mother the scraps from the table; she lives down by the sea-shore, and as I come back I feel tired, and I sit down in the wood to rest, and listen to the nightingale’s song. Then the tears come into my eyes, and it is just as if my mother kissed me.”

“Little maiden,” said the lord-in-waiting, “I will obtain for you constant employment in the kitchen, and you shall have permission to see the emperor dine, if you will lead us to the nightingale; for she is invited for this evening to the palace.”

So she went into the wood where the nightingale sang, and half the court followed her. As they went along, a cow began lowing.

“Oh,” said a young courtier, “now we have found her; what wonderful power for such a small creature; I have certainly heard it before.”

“No, that is only a cow lowing,” said the little girl; “we are a long way from the place yet.”

Then some frogs began to croak in the marsh.

“Beautiful,” said the young courtier again. “Now I hear it, tinkling like little church bells.”

“No, those are frogs,” said the little maiden; “but I think we shall soon hear her now:”

And presently the nightingale began to sing.

“Hark, hark! there she is,” said the girl, “and there she sits,” she added, pointing to a little gray bird who was perched on a bough.

“Is it possible?” said the lord-in-waiting, “I never imagined it would be a little, plain, simple thing like that. She has certainly changed color at seeing so many grand people around her.”

“Little nightingale,” cried the girl, raising her voice, “our most gracious emperor wishes you to sing before him.”

“With the greatest pleasure,” said the nightingale, and began to sing most delightfully.

“It sounds like tiny glass bells,” said the lord-in-waiting, “and see how her little throat works. It is surprising that we have never heard this before; she will be a great success at court.”

“Shall I sing once more before the emperor?” asked the nightingale, who thought he was present.

“My excellent little nightingale,” said the courtier, “I have the great pleasure of inviting you to a court festival this evening, where you will gain imperial favor by your charming song.”

“My song sounds best in the green wood,” said the bird; but still she came willingly when she heard the emperor’s wish.

The palace was elegantly decorated for the occasion. The walls and floors of porcelain glittered in the light of a thousand lamps. Beautiful flowers, round which little bells were tied, stood in the corridors: what with the running to and fro and the draught, these bells tinkled so loudly that no one could speak to be heard.

In the centre of the great hall, a golden perch had been fixed for the nightingale to sit on. The whole court was present, and the little kitchen-maid had received permission to stand by the door. She was not installed as a real court cook. All were in full dress, and every eye was turned to the little gray bird when the emperor nodded to her to begin.

The nightingale sang so sweetly that the tears came into the emperor’s eyes, and then rolled down his cheeks, as her song became still more touching and went to every one’s heart. The emperor was so delighted that he declared the nightingale should have his gold slipper to wear round her neck, but she declined the honor with thanks: she had been sufficiently rewarded already.

“I have seen tears in an emperor’s eyes,” she said, “that is my richest reward. An emperor’s tears have wonderful power, and are quite sufficient honor for me;” and then she sang again more enchantingly than ever.

“That singing is a lovely gift;” said the ladies of the court to each other; and then they took water in their mouths to make them utter the gurgling sounds of the nightingale when they spoke to any one, so thay they might fancy themselves nightingales. And the footmen and chambermaids also expressed their satisfaction, which is saying a great deal, for they are very difficult to please. In fact the nightingale’s visit was most successful.

She was now to remain at court, to have her own cage, with liberty to go out twice a day, and once during the night. Twelve servants were appointed to attend her on these occasions, who each held her by a silken string fastened to her leg. There was certainly not much pleasure in this kind of flying.

The whole city spoke of the wonderful bird, and when two people met, one said “nightin,” and the other said “gale,” and they understood what was meant, for nothing else was talked of. Eleven peddlers’ children were named after her, but not of them could sing a note.

One day the emperor received a large packet on which was written “The Nightingale.”

“Here is no doubt a new book about our celebrated bird,” said the emperor. But instead of a book, it was a work of art contained in a casket, an artificial nightingale made to look like a living one, and covered all over with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires. As soon as the artificial bird was wound up, it could sing like the real one, and could move its tail up and down, which sparkled with silver and gold. Round its neck hung a piece of ribbon, on which was written “The Emperor of China’s nightingale is poor compared with that of the Emperor of Japan’s.”

“This is very beautiful,” exclaimed all who saw it, and he who had brought the artificial bird received the title of “Imperial nightingale-bringer-in-chief.”

“Now they must sing together,” said the court, “and what a duet it will be.”

But they did not get on well, for the real nightingale sang in its own natural way, but the artificial bird sang only waltzes. “That is not a fault,” said the music-master, “it is quite perfect to my taste,” so then it had to sing alone, and was as successful as the real bird; besides, it was so much prettier to look at, for it sparkled like bracelets and breast-pins.

Thirty three times did it sing the same tunes without being tired; the people would gladly have heard it again, but the emperor said the living nightingale ought to sing something. But where was she? No one had noticed her when she flew out at the open window, back to her own green woods.

“What strange conduct,” said the emperor, when her flight had been discovered; and all the courtiers blamed her, and said she was a very ungrateful creature. “But we have the best bird after all,” said one, and then they would have the bird sing again, although it was the thirty-fourth time they had listened to the same piece, and even then they had not learnt it, for it was rather difficult. But the music-master praised the bird in the highest degree, and even asserted that it was better than a real nightingale, not only in its dress and the beautiful diamonds, but also in its musical power.

“For you must perceive, my chief lord and emperor, that with a real nightingale we can never tell what is going to be sung, but with this bird everything is settled. It can be opened and explained, so that people may understand how the waltzes are formed, and why one note follows upon another.”

“This is exactly what we think,” they all replied, and then the music-master received permission to exhibit the bird to the people on the following Sunday, and the emperor commanded that they should be present to hear it sing. When they heard it they were like people intoxicated; however it must have been with drinking tea, which is quite a Chinese custom. They all said “Oh!” and held up their forefingers and nodded, but a poor fisherman, who had heard the real nightingale, said, “it sounds prettily enough, and the melodies are all alike; yet there seems something wanting, I cannot exactly tell what.”

And after this the real nightingale was banished from the empire.

The artificial bird was placed on a silk cushion close to the emperor’s bed. The presents of gold and precious stones which had been received with it were round the bird, and it was now advanced to the title of “Little Imperial Toilet Singer,” and to the rank of No. 1 on the left hand; for the emperor considered the left side, on which the heart lies, as the most noble, and the heart of an emperor is in the same place as that of other people. The music-master wrote a work, in twenty-five volumes, about the artificial bird, which was very learned and very long, and full of the most difficult Chinese words; yet all the people said they had read it, and understood it, for fear of being thought stupid and having their bodies trampled upon.

So a year passed, and the emperor, the court, and all the other Chinese knew every little turn in the artificial bird’s song; and for that same reason it pleased them better. They could sing with the bird, which they often did. The street-boys sang, “Zi-zi-zi, cluck, cluck, cluck,” and the emperor himself could sing it also. It was really most amusing.

One evening, when the artificial bird was singing its best, and the emperor lay in bed listening to it, something inside the bird sounded “whizz.” Then a spring cracked. “Whir-r-r-r” went all the wheels, running round, and then the music stopped.

The emperor immediately sprang out of bed, and called for his physician; but what could he do? Then they sent for a watchmaker; and, after a great deal of talking and examination, the bird was put into something like order; but he said that it must be used very carefully, as the barrels were worn, and it would be impossible to put in new ones without injuring the music. Now there was great sorrow, as the bird could only be allowed to play once a year; and even that was dangerous for the works inside it. Then the music-master made a little speech, full of hard words, and declared that the bird was as good as ever; and, of course no one contradicted him.

Five years passed, and then a real grief came upon the land. The Chinese really were fond of their emperor, and he now lay so ill that he was not expected to live. Already a new emperor had been chosen and the people who stood in the street asked the lord-in-waiting how the old emperor was.

But he only said, “Pooh!” and shook his head.

Cold and pale lay the emperor in his royal bed; the whole court thought he was dead, and every one ran away to pay homage to his successor. The chamberlains went out to have a talk on the matter, and the ladies’-maids invited company to take coffee. Cloth had been laid down on the halls and passages, so that not a footstep should be heard, and all was silent and still. But the emperor was not yet dead, although he lay white and stiff on his gorgeous bed, with the long velvet curtains and heavy gold tassels. A window stood open, and the moon shone in upon the emperor and the artificial bird.

The poor emperor, finding he could scarcely breathe with a strange weight on his chest, opened his eyes, and saw Death sitting there. He had put on the emperor’s golden crown, and held in one hand his sword of state, and in the other his beautiful banner. All around the bed and peeping through the long velvet curtains, were a number of strange heads, some very ugly, and others lovely and gentle-looking. These were the emperor’s good and bad deeds, which stared him in the face now Death sat at his heart.

“Do you remember this?” “Do you recollect that?” they asked one after another, thus bringing to his remembrance circumstances that made the perspiration stand on his brow.

“I know nothing about it,” said the emperor. “Music! music!” he cried; “the large Chinese drum! that I may not hear what they say.”

But they still went on, and Death nodded like a Chinaman to all they said.

“Music! music!” shouted the emperor. “You little precious golden bird, sing, pray sing! I have given you gold and costly presents; I have even hung my golden slipper round your neck. Sing! sing!”

But the bird remained silent. There was no one to wind it up, and therefore it could not sing a note. Death continued to stare at the emperor with his cold, hollow eyes, and the room was fearfully still.

Suddenly there came through the open window the sound of sweet music. Outside, on the bough of a tree, sat the living nightingale. She had heard of the emperor’s illness, and was therefore come to sing to him of hope and trust. And as she sung, the shadows grew paler and paler; the blood in the emperor’s veins flowed more rapidly, and gave life to his weak limbs; and even Death himself listened, and said, “Go on, little nightingale, go on.”

“Then will you give me the beautiful golden sword and that rich banner? and will you give me the emperor’s crown?” said the bird.

So Death gave up each of these treasures for a song; and the nightingale continued her singing. She sung of the quiet churchyard, where the white roses grow, where the elder-tree wafts its perfume on the breeze, and the fresh, sweet grass is moistened by the mourners’ tears. Then Death longed to go and see his garden, and floated out through the window in the form of a cold, white mist.

“Thanks, thanks, you heavenly little bird. I know you well. I banished you from my kingdom once, and yet you have charmed away the evil faces from my bed, and banished Death from my heart, with your sweet song. How can I reward you?”

“You have already rewarded me,” said the nightingale. “I shall never forget that I drew tears from your eyes the first time I sang to you. These are the jewels that rejoice a singer’s heart. But now sleep, and grow strong and well again. I will sing to you again.”

And as she sung, the emperor fell into a sweet sleep; and how mild and refreshing that slumber was!

When he awoke, strengthened and restored, the sun shone brightly through the window; but not one of his servants had returned– they all believed he was dead; only the nightingale still sat beside him, and sang.

“You must always remain with me,” said the emperor. “You shall sing only when it pleases you; and I will break the artificial bird into a thousand pieces.”

“No; do not do that,” replied the nightingale; “the bird did very well as long as it could. Keep it here still. I cannot live in the palace, and build my nest; but let me come when I like. I will sit on a bough outside your window, in the evening, and sing to you, so that you may be happy, and have thoughts full of joy. I will sing to you of those who are happy, and those who suffer; of the good and the evil, who are hidden around you. The little singing bird flies far from you and your court to the home of the fisherman and the peasant’s cot. I love your heart better than your crown; and yet something holy lingers round that also. I will come, I will sing to you; but you must promise me one thing.”

“Everything,” said the emperor, who, having dressed himself in his imperial robes, stood with the hand that held the heavy golden sword pressed to his heart.

“I only ask one thing,” she replied; “let no one know that you have a little bird who tells you everything. It will be best to conceal it.”

So saying, the nightingale flew away.

The servants now came in to look after the dead emperor; when, lo! there he stood, and, to their astonishment, said, “Good morning.”

END

Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales and stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andersen, Andersen, Hans Christian, Archive A-B, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Menno ter Braak

(1902-1940)

De reporter en het asfalt

Zij beiden sloten een hechte vriendschap, toen de tijden rijp waren. Want in het lijden verenigen zich allen.

Waarom moesten zij zich verbinden tot een genegenheid, die alleen onder vertrapten bestaat? Waarom zij, het slaafse asfalt en de reporter, de krullenjongen bij Buitenlands Nieuws? Dit zijn de vragen, die later oprezen, toen het asfalt door een nieuw procédé was vervangen en de reporter in de Eeuwige Jachtvelden ronddoolde en dronk uit het bekkeneel van zijn hoofdredacteur. Het is een raar sprookje gelijk.

Immers zij beiden spiegelden. Spiegelden, spiegelden. Het asfalt, wanneer het vet was van de regen, de reporter, wanneer hij geen last had van zijn maag en op zijn bed bleef liggen. En welk verschil maakt het voor God of men sinaasappeljoden en mooie vrouwen dan wel rijksdagvergaderingen en filmactrices-met-miljonairs-schandalen spiegelt? Staat er niet geschreven: ‘Spiegelt aangenaam voor het oog des Heeren’?

Wat begrepen zij? Werelden van geluk en ellende verwerkten zij als machines; het asfalt werd er steeds wrakker op en de reporter kreeg geen opslag van salaris. Geen van beiden ‘werd er beter van’, zoals de term luidt. Geen genot is het immers de kosmos te verduwen zonder begrip; dit speurde het asfalt, wanneer het zich wat langer wilde verlustigen in een hooggehakt schoentje; dit speurde de reporter als Nieuw-Zeeland en Californië door zijn hersens joegen.

Zielloze media…

Dode tussenstations, die registreren, maar niet scheppen.

Alleen op het asfalt schiep de reporter. Des daags tussen de duizenden, die voortschuifelen en zacht praten. Het asfalt was ònder de reporter en de reporter was òp het asfalt; dit moest, zo overwoog hij, wiskunstig hetzelfde zijn. Toch vond hij het tweede sympathieker, omdat het zijn persoonlijkheid beter deed uitkomen. De indruk was kraniger. Het asfalt was echter slechts onder de mensen, die voorbijschuifelden; vreemd, maar het was zo en het is nòg zo. Het asfalt droeg hèn meer dan dat zij het asfalt trapten… in het oog van de reporter.

Dit waren de onlogische rekensommetjes van de krullenjongen bij Buitenlands Nieuws.

Hij haatte de voorbijschuifelaars en de zachtpraters, omdat hij nog zo jong was. Hij wist niet, dat zij allen goed waren. Sommigen bezochten voor zij gingen winkelen, de mis. Anderen zagen er zo goed uit, dat zij zelfs zonder dit wel zalig zouden worden.

De reporter haatte hen. Maar dat zou terecht komen, als hij promotie maakte. Dan komt immers alles terecht.

Het asfalt zuchtte onder de last en hier en daar werkten gemeentewerklieden om het steviger te maken. De reporter wandelde naar zijn bureau en vloekte, dat het niet aan te horen was. De mensen echter waren zo wijs, zich hieraan niet te storen; zij waren goed en winkelden voort.

‘Maar al het mangaan en goud, dat de tandartsen in hun rottende gebitten stoppen, zal niet voldoende zijn om hun rotte zielen een duizendste seconde uit hun zelfgeschapen hel los te kopen’, zwoer de reporter.

Het zou wel terecht komen… en bovendien had hij zelf drie gevulde kiezen. Zo is de wereld: het zijn de jongelingen, die haar haten en de ouden van dagen, die weten, wat zij waard is. Maar dezen hebben dan ook het meeste goud in hun gebitten, als die althans niet vals zijn.

Des nachts, wanneer door hem heen de nieuwtjes voor het ochtendblad waren geflitst, sukkelde de reporter naar zijn kamer. Als het regende, vlamde het lege asfalt onder de huiverende lantarens. Dat was goed, want als het oudbakken was van de daagse hitte, was het vervelend.

In de nacht vooral schiep de reporter, als reactie op zijn Buitenlands Nieuws. Hij schiep zo geweldig, dat het haast werkelijkheid werd. Eens kwam over het verlaten asfalt, dat in de regen zo heftig kan glanzen, een slanke vrouw op hem toe, heel mooi, heel bleek, in het zwart, zoals in moderne romans. Zij was de schepping van de reporter en een geestelijk kind van het asfalt, maar dat wist de onnozele schepper zelf niet. En dus begeerde hij zijn eigen werk met een heel gewone gedachtenreeks: Ik-ga-met-haar-mee-ze-is-mooi-later-schrijf-ik-een-feuilleton-dat-ik-niet-ben-meegegaan-misschien-krijg-ik-het-wel-geplaatst-en-verder-niet-denken.

Hij naderde, het jonge reportertje met een hunkerend hart en een verlegen gezicht. Maar toen ging het mis. Zijn gehele fantasme brak uiteen in zwarte gitten, die rondspatten over het asfalt. Duisternis verstikte de lantarens en één enkele gouden ster wielde weg, ver op de achtergrond. Als een beleefde agent de reporter niet had opgeraapt, was hij misschien doornat geworden op het natte plein, waar hij zichzelf vond zitten. Zonder veel bewustzijn kwam hij in zijn bed terecht. Het asfalt ònder de reporter; de reporter òp het asfalt… veel verschil maakt het niet, als de reporter in een plas ligt!

Sedert die tijd was de vriendschap tussen hem en het asfalt nog hechter.

Het asfalt gaf raad: ‘Schep niet, wij zijn maar spiegels van het wereldgebeuren, wij zijn maar tussenstations!’

De reporter geloofde het, tot hij door ziekte van een hogergeplaatst collega eens uit zijn berichtjes een Overzicht mocht distilleren. Toen begon hij opnieuw en meermalen liep hij tegen zijn eigen beelden aan.

De reporter maakte promotie, vloekte niet meer, trouwde een niet-geëmancipeerde en toch niet domme vrouw, had des te meer last van zijn maag, maar… reed in een taxi over het asfalt. Elk halfjaar kwam er meer goud in zijn mond.

Het asfalt draagt nog de duizenden, die voortschuifelen en zacht praten. Het vindt alles en allen goed en wenst de ganse mensheid een prettige plaats in de hemel.

Alleen vindt het de taxi van de reporter een onverdraaglijke pedanterie, want door de isolerende rubberbanden is geen vriendschap mogelijk.

Zo gaat het!

Menno ter Braak

20 september 1924

Murena

bron: Menno ter Braak, De Propria Curesartikelen 1923-1925 (ed. Carel Peeters). BZZTôH, Den Haag 1978

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Menno ter Braak

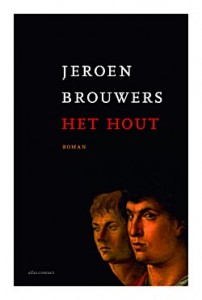

Jeroen Brouwers (1940), oud- AKO Literatuurprijswinnaar, viert met zijn nieuwste langverwachte roman ‘Het hout’, zijn vijftig jarige schrijverschap.

Hierin beschrijft hij een door kloosterlingen geleid jongenspensionaat in de jaren vijftig van de vorige eeuw. In het jongenspensionaat vinden sadisme, sexueel misbruik en vernedering plaats.

Jeroen Brouwers

VPRO Boeken

zondag 28 december 2014

NPO 1, 11.20 uur

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Jeroen Brouwers

Hans Christian Andersen

(1805—1875)

Pen and inkstand

In a poet’s study, somebody made a remark as he looked at the inkstand that was standing on the table: “It’s strange what can come out of that inkstand! I wonder what the next thing will be. Yes, it’s strange!”

“That it is!” said the Inkstand. “It’s unbelievable, that’s what I have always said.” The Inkstand was speaking to the Pen and to everything else on the table that could hear it. “It’s really amazing what comes out of me! Almost incredible! I actually don’t know myself what will come next when that person starts to dip into me. One drop from me is enough for half a piece of paper, and what may not be on it then? I am something quite remarkable. All the works of this poet come from me. These living characters, whom people think they recognize, these deep emotions, that gay humor, the charming descriptions of nature – I don’t understand those myself, because I don’t know anything about nature – all of that is in me. From me have come out, and still come out, that host of lovely maidens and brave knights on snorting steeds. The fact is, I assure you, I don’t know anything about them myself.”

“You are right about that,” said the Pen. “You have very few ideas, and don’t bother about thinking much at all. If you did take the trouble to think, you would understand that nothing comes out of you except a liquid. You just supply me with the means of putting down on paper what I have in me; that’s what I write with. It’s the pen that does the writing. Nobody doubts that, and most people know as much about poetry as an old inkstand!”

“You haven’t had much experience,” retorted the Inkstand. “You’ve hardly been in service a week, and already you’re half worn out. Do you imagine you’re the poet? Why, you’re only a servant; I have had a great many like you before you came, some from the goose family and some of English make. I’m familiar with both quill pens and steel pens. Yes, I’ve had a great many in my service, and I’ll have many more when the man who goes through the motions for me comes to write down what he gets from me. I’d be much interested in knowing what will be the next thing he gets from me.”

“Inkpot!” cried the Pen.

Late that evening the Poet came home. He had been at a concert, had heard a splendid violinist, and was quite thrilled with his marvelous performance. From his instrument he had drawn a golden river of melody. Sometimes it had sounded like the gentle murmur of rippling water drops, wonderful pearl-like tones, sometimes like a chorus of twittering birds, sometimes like a tempest tearing through mighty forests of pine. The Poet had fancied he heard his own heart weep, but in tones as sweet as the gentle voice of a woman. It seemed as if the music came not only from the strings of the violin, but from its sounding board, its pegs, its very bridge. It was amazing! The selection had been extremely difficult, but it had seemed as if the bow were wandering over the strings merely in play. The performance was so easy that an ignorant listener might have thought he could do it himself. The violin seemed to sound, and the bow to play, of their own accord, and one forgot the master who directed them, giving them life and soul. Yes, the master was forgotten, but the Poet remembered him. He repeated his name and wrote down his thoughts.

“How foolish it would be for the violin and bow to boast of their achievements! And yet we human beings often do so. Poets, artists, scientists, generals – we are all proud of ourselves, and yet we’re only instruments in the hands of our Lord! To Him alone be the glory! We have nothing to be arrogant about.”

Yes, that is what the Poet wrote down, and he titled his essay, “The Master and the Instruments.”

“That ought to hold you, madam,” said the Pen, when the two were alone again. “Did you hear him read aloud what I had written?”

“Yes, I heard what I gave you to write,” said the Inkstand. “It was meant for you and your conceit. It’s strange that you can’t tell when anyone is making fun of you. I gave you a pretty sharp cut there; surely I must know my own satire!”

“Inkpot!” said the Pen.

“Scribble-stick!” said the Inkstand.

They were both satisfied with their answers, and it is a great comfort to feel that one has made a witty reply – one sleeps better afterward. So they both went to sleep.

But the Poet didn’t sleep. His thoughts rushed forth like the violin’s tones, falling like pearls, sweeping on like a storm through the forest. He understood the sentiments of his own heart; he caught a ray of the light from the everlasting Master.

To him alone be the glory!

END

Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales and stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andersen, Andersen, Hans Christian, Archive A-B, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

![]()

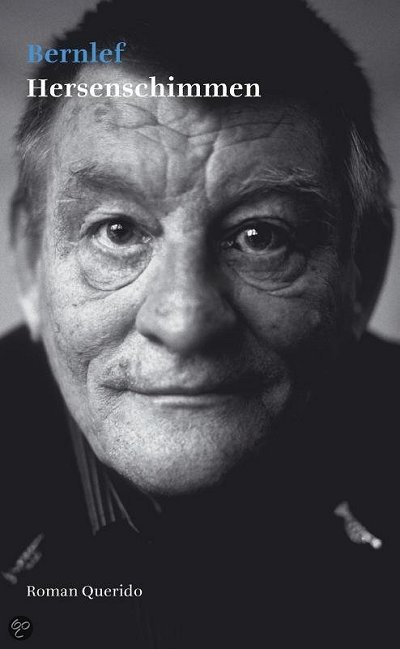

In Memoriam Bernlef

(pseudoniem van: Hendrik Jan Marsman)

In zijn woonplaats Amsterdam is op 29 oktober 2012 na een kortstondig ziekbed de schrijver Bernlef overleden. Hij werd vijfenzeventig jaar. Bernlef publiceerde diverse romans, verhalenbundels, essays en dichtbundels.

MEER IN DINGEN DAN IN MENSEN

Omdat de dood in mensen huist

de buitenkant van dingen is

kan ik alleen in dingen leven zien

Hun stug en tegendraads bestaan

hun onverminderd staren in het zicht

van de mij toegemeten jaren

Daarom zie ik meer in dingen dan in mensen

die een mens die in mij groeit

in richting en in zwijgen naar hen toe.

Uitgeverij Querido treurt om de dood van Bernlef, die meer dan vijftig jaar aan de uitgeverij verbonden was. Uitgever Annette Portegies: “We verliezen niet alleen een geweldige schrijver maar vooral ook een lieve vriend. Iemand bovendien die, vanuit de traditie van ons huis, meedacht over de toekomst van de uitgeverij, en die jonge schrijvers hielp en adviseerde. We zullen hem verschrikkelijk missen.

In 1959 stuurde Bernlef enkele niet eerder gepubliceerde verhalen en gedichten in voor de Reina Prinsen Geerligsprijs, die aan hem werd toegekend. De winnende gedichten verschenen in 1960 in Kokkels en de verhalen in datzelfde jaar in Stenen spoelen. De twee boeken vormen samen zijn debuut.

In de jaren zestig vertaalde Bernlef het werk van diverse Zweedse dichters en schrijvers en recenseerde hij voor onder andere De Groene Amsterdammer, Het Parool, De Gids en Haagse Post. Met G. Brands en K. Schippers begon hij in 1958 het roemruchte tijdschrift Barbarber.

Met de roman Hersenschimmen (1984) brak Bernlef door naar het grote publiek: van het boek zijn in Nederland en Vlaanderen inmiddels bijna een miljoen exemplaren verkocht en het werd in tien talen vertaald. Meer dan een verhaal over dementie is Hersenschimmen een liefdesgeschiedenis, met een onvermijdelijk tragisch einde. In 1988 werd de roman verfilmd door Heddy Honigmann, met Joop Admiraal in de hoofdrol.

De jazz heeft altijd Bernlefs warme belangstelling gehad. Niet alleen dichtte hij over jazz, hij schreef er ook een aantal essays over die in 1993 gebundeld werden in Schiet niet op de pianist en in 1999 in Haalt de jazz de eenentwintigste eeuw? In 2006 publiceerde hij bovendien zijn jazzverhalen in Hoe van de trap te vallen.

Het werk van Bernlef is vaak bekroond. In 1962 kreeg hij de Poëzieprijs van de gemeente Amsterdam voor zijn dichtbundel Morene (1961) en in 1964 de Lucy B. en C.W. van der Hoogtprijs voor Dit verheugd verval (1963). In 1984 werd zijn hele oeuvre bekroond met de Constantijn Huygensprijs. Voor de roman Publiek geheim (1987) kreeg hij de AKO Literatuurprijs en in 1994 werd hem de P.C. Hooftprijs toegekend voor zijn poëzie.

In 2008 schreef Bernlef het Boekenweekgeschenk, onder de titel De pianoman. Nog onlangs verschenen een nieuwe verhalenbundel, Help me herinneren, en zijn verzamelde poëzie, Voorgoed.

Bron: Uitgeverij Querido

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, In Memoriam

Wouter van Riessen

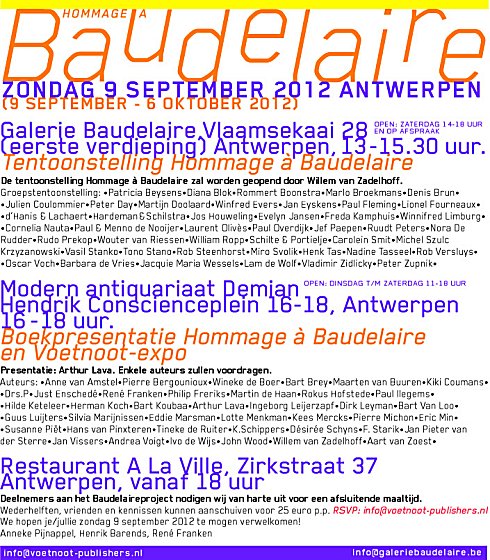

BOEKUITGAVE HOMMAGE À BAUDELAIRE

Uitgeverij Voetnoot bestaat 25 jaar. Galerie Baudelaire bestaat 10 jaar. Oprichters Henrik Barends en Anneke Pijnappel vonden dit aanleiding genoeg om betrokken schrijvers, dichters, vertalers, fotografen en kunstenaars te vragen een hommage aan Baudelaire te maken.

Waarom een hommage aan Baudelaire? Twee motieven liggen hieraan ten grondslag. Voetnoot ging van start met de Nederlandse vertaling van de Kunstkritieken van Charles Baudelaire (1821 – 1867). In zijn kunstkritische beschouwingen stelde deze Franse dichter, schrijver en kunstcriticus de scheppende verbeelding boven het uitbeelden van de zichtbare werkelijkheid. Deze stelling vormt ook het uitgangspunt van van de fotografie die in Galerie Baudelaire wordt getoond. De verrassende bijdragen zijn bijeengebracht in de bundel Hommage à Baudelaire.

De invulling van het thema Baudelaire is vanzelfsprekend prikkelend, uitgesproken, wakkerschuddend, rauw, soms beneveld, soms juist niet, en door de totaal verschillende invalshoeken ook steeds weer boeiend.

Bijdragen: Anne van Amstel, Henrik Barends, Pierre Bergounioux, Patricia Beysens, Diana Blok, Wineke de Boer, Rommert Boonstra, Bart Brey, Marlo Broekmans, Denis Brun, Maarten van Buuren, Julien Coulommier, Kiki Coumans, Peter Day, Martijn Doolaard, Drs.P, Just Enschedé, Winfred Evers, Jan Eyskens, Paul Fleming, Lionel Fourneaux, René Franken, Philip Freriks, d’Hanis & Lachaert, Martin de Haan, Hardeman & Schilstra, Rokus Hofstede, Jos Houweling, Paul Ilegems, Evelyn Jansen, Freda Kamphuis, Hilde Keteleer, Herman Koch, Bart Koubaa, Arthur Lava, Ingeborg Leijerzapf, Dirk Leyman, Winnifred Limburg, Bart Van Loo, Guus Luijters, Sylvia Marijnissen, Eddie Marsman, Lotte Menkman, Kees Mercks, Pierre Michon, Eric Min, Cornelia Nauta, Paul & Menno de Nooijer, Laurent Olivès, Paul Overdijk, Jef Paepen, Ruudt Peters, Susanne Piët, Anneke Pijnappel, Hans van Pinxteren, Rudo Prekop, Wouter van Riessen, William Ropp, Nora De Rudder, Tineke de Ruiter, Schilte & Portielje, K. Schippers, Désirée Schyns, Carolein Smit, Vasil Stanko, Tono Stano, F. Starik, Rob Steenhorst, Jan Pieter van der Sterre, Miro Svolik, Michel Szulc Krzyzanowski, Henk Tas, Nadine Tasseel, Rob Versluys, Jan Vissers, Oscar Voch, Andrea Voigt, Barbara de Vries, Jacquie Maria Wessels, Ivo de Wijs, Lam de Wolf, John Wood, Willem van Zadelhoff, Vladimir Zidlicky, Aart van Zoest, Peter Zupnik

Deze jubileumuitgave bevat 340 pagina’s, 20 x 15,5 cm, is geïllustreerd, is beschikbaar met vier verschillende omslagen en is niet te koop in de boekhandel. In Nederland exclusief verkrijgbaar in de boekwinkel van Bijzondere Collecties UvA, Turfmarkt 129, Amsterdam en via www.voetnootpublishers.nl. Prijs € 15.

BOEKENSALON + EXPO BARENDS & PIJNAPPEL: 19.9/30.9

Op 19 september droeg grafisch vormgever Henrik Barends (Amsterdam, 1945) zijn archief officieel over aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam, afdeling Bijzondere Collecties. Deze overdracht en het jubileum van Uitgeverij Voetnoot vormden de aanleiding tot een feestelijke boekensalon, die vergezeld gaat van een kleine expositie. Museumcafé, Oude Turfmarkt 129, Amsterdam. Dinsdag – vrijdag van 10 – 17 uur, zaterdag – zondag van 13 – 17 uur.

GALERIE BAUDELAIRE – VLAAMSEKAAI 28/ANTWERPEN – 9.9/6.10

Groepstentoonstelling Hommage à Baudelaire met de visuele bijdragen van alle bovengenoemde fotografen en kunstenaars. Open zaterdag 14 – 18 uur en op afspraak. www.galeriebaudelaire.be

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Baudelaire, Charles, Freda Kamphuis

ZONDAG 9 SEPTEMBER 2012 ANTWERPEN

(9 SEPTEMBER – 6 OKTOBER 2012)

Galerie Baudelaire,Vlaamsekaai 28

(eerste verdieping) Antwerpen, 13 – 15.30 uur

Tentoonstelling Hommage à Baudelaire

Modern antiquariaat Demian

Hendrik Conscienceplein 16-18, Antwerpen

16 – 18 uur

Boekpresentatie Hommage à Baudelaire en Voetnoot-expo

Restaurant A La Ville, Zirkstraat 37, Antwerpen, vanaf 18 uur

Groepstentoonstelling: •Patricia Beysens • Diana Blok•Rommert Boonstra • Marlo Broekmans • Denis Brun •Julien Coulommier•Peter Day • Martijn Doolaard•Winfred Evers•Jan Eyskens•Paul Fleming • Lionel Fourneaux • d’Hanis & Lachaert • Hardeman & Schilstra • Jos Houweling • Evelyn Jansen•Freda Kamphuis • Winnifred Limburg • Cornelia Nauta•Paul & Menno de Nooijer • Laurent Olivès • Paul Overdijk • Jef Paepen • Ruudt Peters • Nora De Rudder • Rudo Prekop • Wouter van Riessen•William Ropp •Schilte & Portielje • Carolein Smit•Michel Szulc Krzyzanowski • Vasil Stanko • Tono Stano • Rob Steenhorst • Miro Svolik • Henk Tas•Nadine Tasseel • Rob Versluys • Oscar Voch • Barbara de Vries • Jacquie Maria Wessels • Lam de Wolf • Vladimir Zidlicky • Peter Zupnik •

De tentoonstelling Hommage à Baudelaire zal worden geopend door Willem van Zadelhoff.

Auteurs: •Anne van Amstel •Pierre Bergounioux •Wineke de Boer •Bart Brey •Maarten van Buuren •Kiki Coumans• •Drs.P •Just Enschedé •René Franken •Philip Freriks •Martin de Haan •Rokus Hofstede •Paul Ilegems• •Hilde Keteleer •Herman Koch •Bart Koubaa •Arthur Lava •Ingeborg Leijerzapf •Dirk Leyman •Bart Van Loo• •Guus Luijters •Silvia Marijnissen •Eddie Marsman •Lotte Menkman •Kees Mercks •Pierre Michon •Eric Min• •Susanne Piët •Hans van Pinxteren •Tineke de Ruiter •K.Schippers •Désirée Schyns •F. Starik •Jan Pieter van der Sterre •Jan Vissers •Andrea Voigt •Ivo de Wijs •John Wood •Willem van Zadelhoff •Aart van Zoest•

Presentatie: Arthur Lava. Enkele auteurs zullen voordragen. We hopen je/jullie zondag 9 september 2012 te mogen verwelkomen! Anneke Pijnappel, Henrik Barends, René Franken

OPEN: DINSDAG T/M ZATERDAG 11-18 UUR

OPEN: ZATERDAG 14-18 UUR EN OP AFSPRAAK

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Baudelaire, Charles, Freda Kamphuis

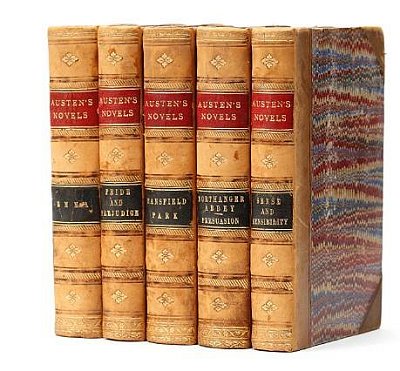

Jane Austen

(1775-1817)

Northanger Abbey

Chapter 10

The Allens, Thorpes, and Morlands all met in the evening at the theatre; and, as Catherine and Isabella sat together, there was then an opportunity for the latter to utter some few of the many thousand things which had been collecting within her for communication in the immeasurable length of time which had divided them. “Oh, heavens! My beloved Catherine, have I got you at last?” was her address on Catherine’s entering the box and sitting by her. “Now, Mr. Morland,” for he was close to her on the other side, “I shall not speak another word to you all the rest of the evening; so I charge you not to expect it. My sweetest Catherine, how have you been this long age? But I need not ask you, for you look delightfully. You really have done your hair in a more heavenly style than ever; you mischievous creature, do you want to attract everybody? I assure you, my brother is quite in love with you already; and as for Mr. Tilney — but that is a settled thing — even your modesty cannot doubt his attachment now; his coming back to Bath makes it too plain. Oh! What would not I give to see him! I really am quite wild with impatience. My mother says he is the most delightful young man in the world; she saw him this morning, you know; you must introduce him to me. Is he in the house now? Look about, for heaven’s sake! I assure you, I can hardly exist till I see him.”

“No,” said Catherine, “he is not here; I cannot see him anywhere.”

“Oh, horrid! Am I never to be acquainted with him? How do you like my gown? I think it does not look amiss; the sleeves were entirely my own thought. Do you know, I get so immoderately sick of Bath; your brother and I were agreeing this morning that, though it is vastly well to be here for a few weeks, we would not live here for millions. We soon found out that our tastes were exactly alike in preferring the country to every other place; really, our opinions were so exactly the same, it was quite ridiculous! There was not a single point in which we differed; I would not have had you by for the world; you are such a sly thing, I am sure you would have made some droll remark or other about it.”

“No, indeed I should not.”

“Oh, yes you would indeed; I know you better than you know yourself. You would have told us that we seemed born for each other, or some nonsense of that kind, which would have distressed me beyond conception; my cheeks would have been as red as your roses; I would not have had you by for the world.”

“Indeed you do me injustice; I would not have made so improper a remark upon any account; and besides, I am sure it would never have entered my head.”

Isabella smiled incredulously and talked the rest of the evening to James.

Catherine’s resolution of endeavouring to meet Miss Tilney again continued in full force the next morning; and till the usual moment of going to the pump–room, she felt some alarm from the dread of a second prevention. But nothing of that kind occurred, no visitors appeared to delay them, and they all three set off in good time for the pump–room, where the ordinary course of events and conversation took place; Mr. Allen, after drinking his glass of water, joined some gentlemen to talk over the politics of the day and compare the accounts of their newspapers; and the ladies walked about together, noticing every new face, and almost every new bonnet in the room. The female part of the Thorpe family, attended by James Morland, appeared among the crowd in less than a quarter of an hour, and Catherine immediately took her usual place by the side of her friend. James, who was now in constant attendance, maintained a similar position, and separating themselves from the rest of their party, they walked in that manner for some time, till Catherine began to doubt the happiness of a situation which, confining her entirely to her friend and brother, gave her very little share in the notice of either. They were always engaged in some sentimental discussion or lively dispute, but their sentiment was conveyed in such whispering voices, and their vivacity attended with so much laughter, that though Catherine’s supporting opinion was not unfrequently called for by one or the other, she was never able to give any, from not having heard a word of the subject. At length however she was empowered to disengage herself from her friend, by the avowed necessity of speaking to Miss Tilney, whom she most joyfully saw just entering the room with Mrs. Hughes, and whom she instantly joined, with a firmer determination to be acquainted, than she might have had courage to command, had she not been urged by the disappointment of the day before. Miss Tilney met her with great civility, returned her advances with equal goodwill, and they continued talking together as long as both parties remained in the room; and though in all probability not an observation was made, nor an expression used by either which had not been made and used some thousands of times before, under that roof, in every Bath season, yet the merit of their being spoken with simplicity and truth, and without personal conceit, might be something uncommon.

“How well your brother dances!” was an artless exclamation of Catherine’s towards the close of their conversation, which at once surprised and amused her companion.

“Henry!” she replied with a smile. “Yes, he does dance very well.”

“He must have thought it very odd to hear me say I was engaged the other evening, when he saw me sitting down. But I really had been engaged the whole day to Mr. Thorpe.” Miss Tilney could only bow. “You cannot think,” added Catherine after a moment’s silence, “how surprised I was to see him again. I felt so sure of his being quite gone away.”

“When Henry had the pleasure of seeing you before, he was in Bath but for a couple of days. He came only to engage lodgings for us.”

“That never occurred to me; and of course, not seeing him anywhere, I thought he must be gone. Was not the young lady he danced with on Monday a Miss Smith?”

“Yes, an acquaintance of Mrs. Hughes.”

“I dare say she was very glad to dance. Do you think her pretty?”

“Not very.”

“He never comes to the pump–room, I suppose?”

“Yes, sometimes; but he has rid out this morning with my father.”

Mrs. Hughes now joined them, and asked Miss Tilney if she was ready to go. “I hope I shall have the pleasure of seeing you again soon,” said Catherine. “Shall you be at the cotillion ball tomorrow?”

“Perhaps we — Yes, I think we certainly shall.”

“I am glad of it, for we shall all be there.” This civility was duly returned; and they parted — on Miss Tilney’s side with some knowledge of her new acquaintance’s feelings, and on Catherine’s, without the smallest consciousness of having explained them.

She went home very happy. The morning had answered all her hopes, and the evening of the following day was now the object of expectation, the future good. What gown and what head–dress she should wear on the occasion became her chief concern. She cannot be justified in it. Dress is at all times a frivolous distinction, and excessive solicitude about it often destroys its own aim. Catherine knew all this very well; her great aunt had read her a lecture on the subject only the Christmas before; and yet she lay awake ten minutes on Wednesday night debating between her spotted and her tamboured muslin, and nothing but the shortness of the time prevented her buying a new one for the evening. This would have been an error in judgment, great though not uncommon, from which one of the other sex rather than her own, a brother rather than a great aunt, might have warned her, for man only can be aware of the insensibility of man towards a new gown. It would be mortifying to the feelings of many ladies, could they be made to understand how little the heart of man is affected by what is costly or new in their attire; how little it is biased by the texture of their muslin, and how unsusceptible of peculiar tenderness towards the spotted, the sprigged, the mull, or the jackonet. Woman is fine for her own satisfaction alone. No man will admire her the more, no woman will like her the better for it. Neatness and fashion are enough for the former, and a something of shabbiness or impropriety will be most endearing to the latter. But not one of these grave reflections troubled the tranquillity of Catherine.

She entered the rooms on Thursday evening with feelings very different from what had attended her thither the Monday before. She had then been exulting in her engagement to Thorpe, and was now chiefly anxious to avoid his sight, lest he should engage her again; for though she could not, dared not expect that Mr. Tilney should ask her a third time to dance, her wishes, hopes, and plans all centred in nothing less. Every young lady may feel for my heroine in this critical moment, for every young lady has at some time or other known the same agitation. All have been, or at least all have believed themselves to be, in danger from the pursuit of someone whom they wished to avoid; and all have been anxious for the attentions of someone whom they wished to please. As soon as they were joined by the Thorpes, Catherine’s agony began; she fidgeted about if John Thorpe came towards her, hid herself as much as possible from his view, and when he spoke to her pretended not to hear him. The cotillions were over, the country–dancing beginning, and she saw nothing of the Tilneys.

“Do not be frightened, my dear Catherine,” whispered Isabella, “but I am really going to dance with your brother again. I declare positively it is quite shocking. I tell him he ought to be ashamed of himself, but you and John must keep us in countenance. Make haste, my dear creature, and come to us. John is just walked off, but he will be back in a moment.”

Catherine had neither time nor inclination to answer. The others walked away, John Thorpe was still in view, and she gave herself up for lost. That she might not appear, however, to observe or expect him, she kept her eyes intently fixed on her fan; and a self–condemnation for her folly, in supposing that among such a crowd they should even meet with the Tilneys in any reasonable time, had just passed through her mind, when she suddenly found herself addressed and again solicited to dance, by Mr. Tilney himself. With what sparkling eyes and ready motion she granted his request, and with how pleasing a flutter of heart she went with him to the set, may be easily imagined. To escape, and, as she believed, so narrowly escape John Thorpe, and to be asked, so immediately on his joining her, asked by Mr. Tilney, as if he had sought her on purpose! — it did not appear to her that life could supply any greater felicity.

Scarcely had they worked themselves into the quiet possession of a place, however, when her attention was claimed by John Thorpe, who stood behind her. “Heyday, Miss Morland!” said he. “What is the meaning of this? I thought you and I were to dance together.”

“I wonder you should think so, for you never asked me.”

“That is a good one, by Jove! I asked you as soon as I came into the room, and I was just going to ask you again, but when I turned round, you were gone! This is a cursed shabby trick! I only came for the sake of dancing with you, and I firmly believe you were engaged to me ever since Monday. Yes; I remember, I asked you while you were waiting in the lobby for your cloak. And here have I been telling all my acquaintance that I was going to dance with the prettiest girl in the room; and when they see you standing up with somebody else, they will quiz me famously.”

“Oh, no; they will never think of me, after such a description as that.”

“By heavens, if they do not, I will kick them out of the room for blockheads. What chap have you there?” Catherine satisfied his curiosity. “Tilney,” he repeated. “Hum — I do not know him. A good figure of a man; well put together. Does he want a horse? Here is a friend of mine, Sam Fletcher, has got one to sell that would suit anybody. A famous clever animal for the road — only forty guineas. I had fifty minds to buy it myself, for it is one of my maxims always to buy a good horse when I meet with one; but it would not answer my purpose, it would not do for the field. I would give any money for a real good hunter. I have three now, the best that ever were backed. I would not take eight hundred guineas for them. Fletcher and I mean to get a house in Leicestershire, against the next season. It is so d — uncomfortable, living at an inn.”

This was the last sentence by which he could weary Catherine’s attention, for he was just then borne off by the resistless pressure of a long string of passing ladies. Her partner now drew near, and said, “That gentleman would have put me out of patience, had he stayed with you half a minute longer. He has no business to withdraw the attention of my partner from me. We have entered into a contract of mutual agreeableness for the space of an evening, and all our agreeableness belongs solely to each other for that time. Nobody can fasten themselves on the notice of one, without injuring the rights of the other. I consider a country–dance as an emblem of marriage. Fidelity and complaisance are the principal duties of both; and those men who do not choose to dance or marry themselves, have no business with the partners or wives of their neighbours.”

“But they are such very different things!”

“ — That you think they cannot be compared together.”

“To be sure not. People that marry can never part, but must go and keep house together. People that dance only stand opposite each other in a long room for half an hour.”

“And such is your definition of matrimony and dancing. Taken in that light certainly, their resemblance is not striking; but I think I could place them in such a view. You will allow, that in both, man has the advantage of choice, woman only the power of refusal; that in both, it is an engagement between man and woman, formed for the advantage of each; and that when once entered into, they belong exclusively to each other till the moment of its dissolution; that it is their duty, each to endeavour to give the other no cause for wishing that he or she had bestowed themselves elsewhere, and their best interest to keep their own imaginations from wandering towards the perfections of their neighbours, or fancying that they should have been better off with anyone else. You will allow all this?”

“Yes, to be sure, as you state it, all this sounds very well; but still they are so very different. I cannot look upon them at all in the same light, nor think the same duties belong to them.”

“In one respect, there certainly is a difference. In marriage, the man is supposed to provide for the support of the woman, the woman to make the home agreeable to the man; he is to purvey, and she is to smile. But in dancing, their duties are exactly changed; the agreeableness, the compliance are expected from him, while she furnishes the fan and the lavender water. That, I suppose, was the difference of duties which struck you, as rendering the conditions incapable of comparison.”

“No, indeed, I never thought of that.”

“Then I am quite at a loss. One thing, however, I must observe. This disposition on your side is rather alarming. You totally disallow any similarity in the obligations; and may I not thence infer that your notions of the duties of the dancing state are not so strict as your partner might wish? Have I not reason to fear that if the gentleman who spoke to you just now were to return, or if any other gentleman were to address you, there would be nothing to restrain you from conversing with him as long as you chose?”

“Mr. Thorpe is such a very particular friend of my brother’s, that if he talks to me, I must talk to him again; but there are hardly three young men in the room besides him that I have any acquaintance with.”

“And is that to be my only security? Alas, alas!”

“Nay, I am sure you cannot have a better; for if I do not know anybody, it is impossible for me to talk to them; and, besides, I do not want to talk to anybody.”

“Now you have given me a security worth having; and I shall proceed with courage. Do you find Bath as agreeable as when I had the honour of making the inquiry before?”

“Yes, quite — more so, indeed.”

“More so! Take care, or you will forget to be tired of it at the proper time. You ought to be tired at the end of six weeks.”

“I do not think I should be tired, if I were to stay here six months.”

“Bath, compared with London, has little variety, and so everybody finds out every year. ‘For six weeks, I allow Bath is pleasant enough; but beyond that, it is the most tiresome place in the world.’ You would be told so by people of all descriptions, who come regularly every winter, lengthen their six weeks into ten or twelve, and go away at last because they can afford to stay no longer.”

“Well, other people must judge for themselves, and those who go to London may think nothing of Bath. But I, who live in a small retired village in the country, can never find greater sameness in such a place as this than in my own home; for here are a variety of amusements, a variety of things to be seen and done all day long, which I can know nothing of there.”

“You are not fond of the country.”

“Yes, I am. I have always lived there, and always been very happy. But certainly there is much more sameness in a country life than in a Bath life. One day in the country is exactly like another.”

“But then you spend your time so much more rationally in the country.”

“Do I?”

“Do you not?”

“I do not believe there is much difference.”

“Here you are in pursuit only of amusement all day long.”

“And so I am at home — only I do not find so much of it. I walk about here, and so I do there; but here I see a variety of people in every street, and there I can only go and call on Mrs. Allen.”

Mr. Tilney was very much amused.

“Only go and call on Mrs. Allen!” he repeated. “What a picture of intellectual poverty! However, when you sink into this abyss again, you will have more to say. You will be able to talk of Bath, and of all that you did here.”

“Oh! Yes. I shall never be in want of something to talk of again to Mrs. Allen, or anybody else. I really believe I shall always be talking of Bath, when I am at home again — I do like it so very much. If I could but have Papa and Mamma, and the rest of them here, I suppose I should be too happy! James’s coming (my eldest brother) is quite delightful — and especially as it turns out that the very family we are just got so intimate with are his intimate friends already. Oh! Who can ever be tired of Bath?”

“Not those who bring such fresh feelings of every sort to it as you do. But papas and mammas, and brothers, and intimate friends are a good deal gone by, to most of the frequenters of Bath — and the honest relish of balls and plays, and everyday sights, is past with them.” Here their conversation closed, the demands of the dance becoming now too importunate for a divided attention.

Soon after their reaching the bottom of the set, Catherine perceived herself to be earnestly regarded by a gentleman who stood among the lookers–on, immediately behind her partner. He was a very handsome man, of a commanding aspect, past the bloom, but not past the vigour of life; and with his eye still directed towards her, she saw him presently address Mr. Tilney in a familiar whisper. Confused by his notice, and blushing from the fear of its being excited by something wrong in her appearance, she turned away her head. But while she did so, the gentleman retreated, and her partner, coming nearer, said, “I see that you guess what I have just been asked. That gentleman knows your name, and you have a right to know his. It is General Tilney, my father.”

Catherine’s answer was only “Oh!” — but it was an “Oh!” expressing everything needful: attention to his words, and perfect reliance on their truth. With real interest and strong admiration did her eye now follow the general, as he moved through the crowd, and “How handsome a family they are!” was her secret remark.

In chatting with Miss Tilney before the evening concluded, a new source of felicity arose to her. She had never taken a country walk since her arrival in Bath. Miss Tilney, to whom all the commonly frequented environs were familiar, spoke of them in terms which made her all eagerness to know them too; and on her openly fearing that she might find nobody to go with her, it was proposed by the brother and sister that they should join in a walk, some morning or other. “I shall like it,” she cried, “beyond anything in the world; and do not let us put it off — let us go tomorrow.” This was readily agreed to, with only a proviso of Miss Tilney’s, that it did not rain, which Catherine was sure it would not. At twelve o’clock, they were to call for her in Pulteney Street; and “Remember — twelve o’clock,” was her parting speech to her new friend. Of her other, her older, her more established friend, Isabella, of whose fidelity and worth she had enjoyed a fortnight’s experience, she scarcely saw anything during the evening. Yet, though longing to make her acquainted with her happiness, she cheerfully submitted to the wish of Mr. Allen, which took them rather early away, and her spirits danced within her, as she danced in her chair all the way home.

Jane Austen novel: Northanger Abbey, Chapter 10

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

Nieuwe Kinderstadsdichter

Pleun Andriessen

gehuldigd

Op maandag 29 augustus wordt de 10-jarige Pleun Andriessen officieel benoemd tot Kinderstadsdichter van Tilburg. Ze neemt dan het stokje over van Sara Bidaoui, die deze functie vanaf januari 2010 bekleed heeft. Pleun wordt op 29 augustus officieel gehuldigd door wethouder Marieke Moorman op basisschool De Borne in de Blaak. Ook Esther Porcelijn, de nieuwe stadsdichter van Tilburg, zal dan aanwezig zijn om haar collega welkom te heten.

Pleun won de titel Kinderstadsdichter met haar gedicht “Thuis???” en wordt Kinderstadsdichter voor de periode van een jaar. In het kader van deze feestelijkheden krijgen de leerlingen van de Borne een introductie op het thema van de Kinderstadsdichtwedstrijd: Tilburg, mijn stad, mijn thuis. Ze gaan zelf ook aan het dichten en zullen hun stadsgedichten tijdens de feestelijke huldiging op het podium ten gehore brengen.

Het openbare programma op basisschool De Borne vindt plaats van 11u00 tot 12u00. Het winnende gedicht van Pleun is te lezen op: www.kinderstadsdichter.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andriessen, Pleun, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Kinderstadsdichters / Children City Poets

.jpg)

Charles Baudelaire

Op winterdagen na het stille eten

denk ik vaak met de borstel aan de vaat

van alle poëzie is hij de maat

dat zweer ik op de bloedzucht van mijn neten

hij leefde aan de oever langs de Lethe

waar vrouwen syf schonken in ruil voor zaad

als waren zij de bloemen van het kwaad

van zoete folter leek zijn geest bezeten.

Op winterdagen na een karig maal

zwoer hij de wereld af voor dure plichten

dan schreef hij verzen op een wand van staal

en kerfde zich een weg naar zijn gedichten

waarmee hij als fantoom, welhaast rectaal

de klok van onlust luidde in gestichten.

Kees Godefrooij

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Archive G-H, Baudelaire, Charles, Godefrooij, Kees

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature