Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

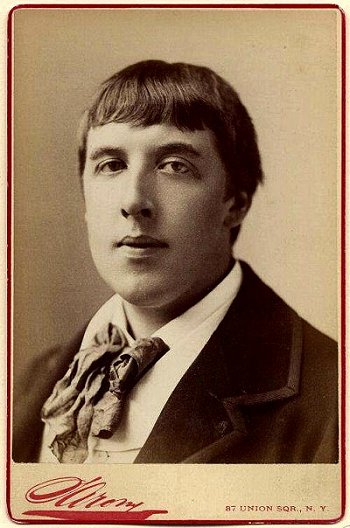

OSCAR WILDE

(1854-1900)

Pan. Double Villanelle

I

O Goat-foot God of Arcady!

This modern world is grey and old,

And what remains to us of Thee?

No more the shepherd lads in glee

Throw apples at thy wattled fold,

O Goat-foot God of Arcady!

Nor through the laurels can one see

Thy soft brown limbs, thy beard of gold,

And what remains to us of Thee?

And dull and dead our Thames would be

For here the winds are chill and cold,

O goat-foot God of Arcady!

Then keep the tomb of Helice,

Thine olive-woods, thy vine-clad wold,

Ah what remains to us of Thee?

Though many an unsung elegy

Sleeps in the reeds our rivers hold,

O Goat-foot God of Arcady!

Ah, what remains to us of Thee?

II

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady,

Thy satyrs and their wanton play,

This modern world hath need of Thee.

No nymph or Faun indeed have we,

Faun and nymph are old and grey,

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady!

This is the land where Liberty

Lit grave-browed Milton on his way,

This modern world hath need of Thee!

A land of ancient chivalry

Where gentle Sidney saw the day,

Ah, leave the hills of Arcady!

This fierce sea-lion of the sea,

This England, lacks some stronger lay,

This modern world hath need of Thee!

Then blow some Trumpet loud and free,

And give thine oaten pipe away,

Ah leave the hills of Arcady!

This modern world hath need of Thee!

Pan. Villanella in tweevoud

I

O Herdersgod met bokkevoet!

De wereld is nu grijs en oud,

En is er iets dat jij nog doet?

Geen herder die jou blij ontmoet

En zich tot appelworp verstout,

O Herdersgod met bokkevoet!

Noch iemand die in ’t bos begroet

Jouw poot zacht, bruin, jouw baard van goud,

En is er iets dat jij nog doet?

De Theems zou dood zijn, zonder vloed,

Want hier zijn winden straf en koud,

O Herdersgod met bokkevoet!

Dus veins dat je Helice behoedt,

Je wijngaard, je olijvenwoud,

En is er iets dat jij nog doet?

Ofschoon veel treurzang men vermoedt

Die ’t riet van beken in zich houdt,

O Herdersgod met bokkevoet!

Is er ook iets dat jij nog doet?

II

Verlaat Arcadië toch gauw,

Waar men de satyrs stoeien ziet,

De nieuwe tijd heeft baat bij jou.

Geen Faun of nimf is hier in touw,

Want Faun en nimf gedijen niet,

Verlaat Arcadië toch gauw!

Dit land is aan zijn Vrijheid trouw,

Waar Milton’s ernst zich op verliet,

De nieuwe tijd heeft baat bij jou.

Een land dat Sidney dienen zou,

Dat oude ridderlijk gebied,

Verlaat Arcadië toch gauw!

Dit zeeleeuwland met scherpe klauw,

Dit Engeland vraagt sterker lied,

De nieuwe tijd heeft baat bij jou!.

Bazuin wat ieder horen zou,

Doe afstand van je herdersriet

Verlaat Arcadië toch gauw!

De nieuwe tijd heeft baat bij jou!

VALLEND BLOEMBLAD

Verzamelde korte gedichten van OSCAR WILDE

Vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld

tweetalige uitgave, 2012 (niet gepubliceerd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Wilde, Oscar

Virginia Woolf

How Should One Read a Book?

In the first place, I want to emphasize the note of interrogation at the end of my title. Even if I could answer the question for myself, the answer would apply only to me and not to you. The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. If this is agreed between us, then I feel at liberty to put forward a few ideas and suggestions because you will not allow them to fetter that independence which is the most important quality that a reader can possess. After all, what laws can be laid down about books? The battle of Waterloo was certainly fought on a certain day; but is Hamlet a better play than Lear? Nobody can say. Each must decide that question for himself. To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions—there we have none.

But to enjoy freedom, if the platitude is pardonable, we have of course to control ourselves. We must not squander our powers, helplessly and ignorantly, squirting half the house in order to water a single rose-bush; we must train them, exactly and powerfully, here on the very spot. This, it may be, is one of the first difficulties that faces us in a library. What is “the very spot?” There may well seem to be nothing but a conglomeration and huddle of confusion. Poems and novels, histories and memories, dictionaries and blue-books; books written in all languages by men and women of all tempers, races, and ages jostle each other on the shelf. And outside the donkey brays, the women gossip at the pump, the colts gallop across the fields. Where are we to begin? How are we to bring order into this multitudinous chaos and so get the deepest and widest pleasure from what we read?

It is simple enough to say that since books have classes—fiction, biography, poetry—we should separate them and take from each what it is right that each should give us. Yet few people ask from books what books can give us. Most commonly we come to books with blurred and divided minds, asking of fiction that it shall be true, of poetry that it shall be false, of biography that it shall be flattering, of history that it shall enforce our own prejudices. If we could banish all such preconceptions when we read, that would be an admirable beginning. Do not dictate to your author; try to become him. Be his fellow-worker and accomplice. If you hang back, and reserve and criticize at first, you are preventing yourself from getting the fullest possible value from what you read. But if you open your mind as widely as possible, then signs and hints of almost imperceptible fineness, from the twist and turn of the first sentences, will bring you into the presence of a human being unlike any other. Steep yourself in this, acquaint yourself with this, and soon you will find that your author is giving you, or attempting to give you, something far more definite. The thirty-chapters of a novel—if we consider how to read a novel first—are an attempt to make something as formed and controlled as a building: but words are more impalpable than bricks; reading is a longer and more complicated process than seeing. Perhaps the quickest way to understand the elements of what a novelist is doing is not to read, but to write; to make your own experiment with the dangers and difficulties of words. Recall, then, some event that has left a distinct impression on you— how at the corner of the street, perhaps, you passed two people talking. A tree shook; an electric light danced; the tone of the talk was comic, but also tragic; a whole vision, an entire conception, seemed contained in that moment.

But when you attempt to reconstruct it in words, you will find that it breaks into a thousand conflicting impressions. Some must be subdued; others emphasized; in the process you will lose, probably, all grasp upon the emotion itself. Then turn from your blurred and littered pages to the opening pages of some great novelist—Defoe, Jane Austen, Hardy. Now you will be better able to appreciate their mastery. It is not merely that we are in the presence of a different person—Defoe, Jane Austen, or Thomas Hardy—but that we are living in a different world. Here, in Robinson Crusoe, we are trudging a plain high road; one thing happens after another; the fact and the order of the fact is enough. But if the open air and adventure mean everything to Defoe they mean nothing to Jane Austen. Hers is the drawing-room, and people talking, and by the many mirrors of their talk revealing their characters. And if, when we have accustomed ourselves to the drawing-room and its reflections, we turn to Hardy, we are once more spun round. The moors are round us and the stars are above our heads. The other side of the mind is now exposed—the dark side that comes uppermost in solitude, not the light side that shows in company. Our relations are not towards people, but towards Nature and destiny. Yet different as these worlds are, each is consistent with itself. The maker of each is careful to observe the laws of his own perspective, and however great a strain they may put upon us they will never confuse us, as lesser writers so frequently do, by introducing two different kinds of reality into the same book. Thus to go from one great novelist to another—from Jane Austen to Hardy, from Peacock to Trollope, from Scott to Meredith—is to be wrenched and uprooted; to be thrown this way and then that. To read a novel is a difficult and complex art. You must be capable not only of great fineness of perception, but of great boldness of imagination if you are going to make use of all that the novelist—the great artist—gives you.

But a glance at the heterogeneous company on the shelf will show you that writers are very seldom “great artists;” far more often a book makes no claim to be a work of art at all. These biographies and autobiographies, for example, lives of great men, of men long dead and forgotten, that stand cheek by jowl with the novels and poems, are we to refuse to read them because they are not “art?” Or shall we read them, but read them in a different way, with a different aim? Shall we read them in the first place to satisfy that curiosity which possesses us sometimes when in the evening we linger in front of a house where the lights are lit and the blinds not yet drawn, and each floor of the house shows us a different section of human life in being? Then we are consumed with curiosity about the lives of these people—the servants gossiping, the gentlemen dining, the girl dressing for a party, the old woman at the window with her knitting. Who are they, what are they, what are their names, their occupations, their thoughts, and adventures?

Biographies and memoirs answer such questions, light up innumerable such houses; they show us people going about their daily affairs, toiling, failing, succeeding, eating, hating, loving, until they die. And sometimes as we watch, the house fades and the iron railings vanish and we are out at sea; we are hunting, sailing, fighting; we are among savages and soldiers; we are taking part in great campaigns. Or if we like to stay here in England, in London, still the scene changes; the street narrows; the house becomes small, cramped, diamond-paned, and malodorous. We see a poet, Donne, driven from such a house because the walls were so thin that when the children cried their voices cut through them. We can follow him, through the paths that lie in the pages of books, to Twickenham; to Lady Bedford’s Park, a famous meeting-ground for nobles and poets; and then turn our steps to Wilton, the great house under the downs, and hear Sidney read the Arcadia to his sister; and ramble among the very marshes and see the very herons that figure in that famous romance; and then again travel north with that other Lady Pembroke, Anne Clifford, to her wild moors, or plunge into the city and control our merriment at the sight of Gabriel Harvey in his black velvet suit arguing about poetry with Spenser. Nothing is more fascinating than to grope and stumble in the alternate darkness and splendor of Elizabethan London. But there is no staying there. The Temples and the Swifts, the Harleys and the St Johns beckon us on; hour upon hour can be spent disentangling their quarrels and deciphering their characters; and when we tire of them we can stroll on, past a lady in black wearing diamonds, to Samuel Johnson and Goldsmith and Garrick; or cross the channel, if we like, and meet Voltaire and Diderot, Madame du Deffand; and so back to England and Twickenham—how certain places repeat themselves and certain names!—where Lady Bedford had her Park once and Pope lived later, to Walpole’s home at Strawberry Hill. But Walpole introduces us to such a swarm of new acquaintances, there are so many houses to visit and bells to ring that we may well hesitate for a moment, on the Miss Berrys’ doorstep, for example, when behold, up comes Thackeray; he is the friend of the woman whom Walpole loved; so that merely by going from friend to friend, from garden to garden, from house to house, we have passed from one end of English literature to another and wake to find ourselves here again in the present, if we can so differentiate this moment from all that have gone before. This, then, is one of the ways in which we can read these lives and letters; we can make them light up the many windows of the past; we can watch the famous dead in their familiar habits and fancy sometimes that we are very close and can surprise their secrets, and sometimes we may pull out a play or a poem that they have written and see whether it reads differently in the presence of the author. But this again rouses other questions. How far, we must ask ourselves, is a book influenced by its writer’s life—how far is it safe to let the man interpret the writer? How far shall we resist or give way to the sympathies and antipathies that the man himself rouses in us—so sensitive are words, so receptive of the character of the author? These are questions that press upon us when we read lives and letters, and we must answer them for ourselves, for nothing can be more fatal than to be guided by the preferences of others in a matter so personal.

But also we can read such books with another aim, not to throw light on literature, not to become familiar with famous people, but to refresh and exercise our own creative powers. Is there not an open window on the right hand of the bookcase? How delightful to stop reading and look out! How stimulating the scene is, in its unconsciousness, its irrelevance, its perpetual movement—the colts galloping round the field, the woman filling her pail at the well, the donkey throwing back his head and emitting his long, acrid moan. The greater part of any library is nothing but the record of such fleeting moments in the lives of men, women, and donkeys. Every literature, as it grows old, has its rubbish-heap, its record of vanished moments and forgotten lives told in faltering and feeble accents that have perished. But if you give yourself up to the delight of rubbish-reading you will be surprised, indeed you will be overcome, by the relics of human life that have been cast out to molder. It may be one letter—but what a vision it gives! It may be a few sentences—but what vistas they suggest! Sometimes a whole story will come together with such beautiful humor and pathos and completeness that it seems as if a great novelist had been at work, yet it is only an old actor, Tate Wilkinson, remembering the strange story of Captain Jones; it is only a young subaltern serving under Arthur Wellesley and falling in love with a pretty girl at Lisbon; it is only Maria Allen letting fall her sewing in the empty drawing-room and sighing how she wishes she had taken Dr Burney’s good advice and had never eloped with her Rishy. None of this has any value; it is negligible in the extreme; yet how absorbing it is now and again to go through the rubbish-heaps and find rings and scissors and broken noses buried in the huge past and try to piece them together while the colt gallops round the field, the woman fills her pail at the well, and the donkey brays.

But we tire of rubbish-reading in the long run. We tire of searching for what is needed to complete the half-truth which is all that the Wilkinsons, the Bunburys and the Maria Allens are able to offer us. They had not the artist’s power of mastering and eliminating; they could not tell the whole truth even about their own lives; they have disfigured the story that might have been so shapely. Facts are all that they can offer us, and facts are a very inferior form of fiction. Thus the desire grows upon us to have done with half-statements and approximations; to cease from searching out the minute shades of human character, to enjoy the greater abstractness, the purer truth of fiction. Thus we create the mood, intense and generalized, unaware of detail, but stressed by some regular, recurrent beat, whose natural expression is poetry; and that is the time to read poetry when we are almost able to write it.

Western wind, when wilt thou blow?

The small rain down can rain.

Christ, if my love were in my arms,

And I in my bed again!

The impact of poetry is so hard and direct that for the moment there is no other sensation except that of the poem itself. What profound depths we visit then—how sudden and complete is our immersion! There is nothing here to catch hold of; nothing to stay us in our flight. The illusion of fiction is gradual; its effects are prepared; but who when they read these four lines stops to ask who wrote them, or conjures up the thought of Donne’s house or Sidney’s secretary; or enmeshes them in the intricacy of the past and the succession of generations? The poet is always our contemporary. Our being for the moment is centered and constricted, as in any violent shock of personal emotion. Afterwards, it is true, the sensation begins to spread in wider rings through our minds; remoter senses are reached; these begin to sound and to comment and we are aware of echoes and reflections. The intensity of poetry covers an immense range of emotion. We have only to compare the force and directness of

I shall fall like a tree, and find my grave,

Only remembering that I grieve,

with the wavering modulation of

Minutes are numbered by the fall of sands,

As by an hour glass; the span of time

Doth waste us to our graves, and we look on it;

An age of pleasure, revelled out, comes home

At last, and ends in sorrow; but the life,

Weary of riot, numbers every sand,

Wailing in sighs, until the last drop down,

So to conclude calamity in rest

or place the meditative calm of

whether we be young or old,

Our destiny, our being’s heart and home,

Is with infinitude, and only there;

With hope it is, hope that can never die,

Effort, and expectation, and desire,

And effort evermore about to be,

beside the complete and inexhaustible loveliness of

The moving Moon went up the sky,

And nowhere did abide:

Softly she was going up,

And a star or two beside—

or the splendid fantasy of

And the woodland haunter

Shall not cease to saunter

When, far down some glade,

Of the great world’s burning,

One soft flame upturning

Seems to his discerning,

Crocus in the shade,

to bethink us of the varied art of the poet; his power to make us at once actors and spectators; his power to run his hand into characters as if it were a glove, and be Falstaff or Lear; his power to condense, to widen, to state, once and for ever.

“We have only to compare”—with those words the cat is out of the bag, and the true complexity of reading is admitted. The first process, to receive impressions with the utmost understanding, is only half the process of reading; it must be completed, if we are to get the whole pleasure from a book, by another. We must pass judgment upon these multitudinous impressions; we must make of these fleeting shapes one that is hard and lasting. But not directly. Wait for the dust of reading to settle; for the conflict and the questioning to die down; walk, talk, pull the dead petals from a rose, or fall asleep. Then suddenly without our willing it, for it is thus that Nature undertakes these transitions, the book will return, but differently. It will float to the top of the mind as a whole. And the book as a whole is different from the book received currently in separate phrases. Details now fit themselves into their places. We see the shape from start to finish; it is a barn, a pig-sty, or a cathedral. Now then we can compare book with book as we compare building with building. But this act of comparison means that our attitude has changed; we are no longer the friends of the writer, but his judges; and just as we cannot be too sympathetic as friends, so as judges we cannot be too severe. Are they not criminals, books that have wasted our time and sympathy; are they not the most insidious enemies of society, corrupters, defilers, the writers of false books, faked books, books that fill the air with decay and disease? Let us then be severe in our judgments; let us compare each book with the greatest of its kind. There they hang in the mind the shapes of the books we have read solidified by the judgments we have passed on them—Robinson Crusoe, Emma The Return of the Native. Compare the novels with these—even the latest and least of novels has a right to be judged with the best. And so with poetry when the intoxication of rhythm has died down and the splendor of words has faded, a visionary shape will return to us and this must be compared with Lear, with Phèdre, with The Prelude; or if not with these, with whatever is the best or seems to us to be the best in its own kind. And we may be sure that the newness of new poetry and fiction is its most superficial quality and that we have only to alter slightly, not to recast, the standards by which we have judged the old.

It would be foolish, then, to pretend that the second part of reading, to judge, to compare, is as simple as the first—to open the mind wide to the fast flocking of innumerable impressions. To continue reading without the book before you, to hold one shadow-shape against another, to have read widely enough and with enough understanding to make such comparisons alive and illuminating—that is difficult; it is still more difficult to press further and to say, “Not only is the book of this sort, but it is of this value; here it fails; here it succeeds; this is bad; that is good.” To carry out this part of a reader’s duty needs such imagination, insight, and learning that it is hard to conceive any one mind sufficiently endowed; impossible for the most self-confident to find more than the seeds of such powers in himself. Would it not be wiser, then, to remit this part of reading and to allow the critics, the gowned and furred authorities of the library, to decide the question of the book’s absolute value for us? Yet how impossible! We may stress the value of sympathy; we may try to sink our own identity as we read. But we know that we cannot sympathize wholly or immerse ourselves wholly; there is always a demon in us who whispers, “I hate, I love,” and we cannot silence him. Indeed, it is precisely because we hate and we love that our relation with the poets and novelists is so intimate that we find the presence of another person intolerable. And even if the results are abhorrent and our judgments are wrong, still our taste, the nerve of sensation that sends shocks through us, is our chief illuminant; we learn through feeling; we cannot suppress our own idiosyncrasy without impoverishing it. But as time goes on perhaps we can train our taste; perhaps we can make it submit to some control. When it has fed greedily and lavishly upon books of all sorts—poetry, fiction, history, biography—and has stopped reading and looked for long spaces upon the variety, the incongruity of the living world, we shall find that it is changing a little; it is not so greedy, it is more reflective. It will begin to bring us not merely judgments on particular books, but it will tell us that there is a quality common to certain books. Listen, it will say, what shall we call this? And it will read us perhaps Lear and then perhaps the Agamemnon in order to bring out that common quality. Thus, with our taste to guide us, we shall venture beyond the particular book in search of qualities that group books together; we shall give them names and thus frame a rule that brings order into our perceptions. We shall gain a further and a rarer pleasure from that discrimination. But as a rule only lives when it is perpetually broken by contact with the books themselves—nothing is easier and more stultifying than to make rules which exists out of touch with facts, in a vacuum—now at last, in order to steady ourselves in this difficult attempt, it may be well to turn to the very rare writers who are able to enlighten us upon literature as an art. Coleridge and Dryden and Johnson, in their considered criticism, the poets and novelists themselves in their unconsidered sayings, are often surprisingly relevant; they light up and solidify the vague ideas that have been tumbling in the misty depths of our minds. But they are only able to help us if we come to them laden with questions and suggestions won honestly in the course of our own reading. They can do nothing for us if we herd ourselves under their authority and lie down like sheep in the shade of a hedge. We can only understand their ruling when it comes in conflict with our own and vanquishes it.

If this is so, if to read a book as it should be read calls for the rarest qualities of imagination, insight, and judgment, and you may perhaps conclude that literature is a very complex art and that it is unlikely that we shall be able, even after a lifetime of reading, to make any valuable contribution to its criticism. We must remain readers; we shall not put on the further glory that belongs to those rare beings who are also critics. But still we have our responsibilities as readers and even our importance. The standards we raise and the judgments we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work. An influence is created which tells upon them even if it never finds its way into print. And that influence, if it were well instructed, vigorous and individual and sincere, might be of great value now when criticism is necessarily in abeyance; when books pass in review like the procession of animals in a shooting gallery, and the critic has only one second in which to load and aim and shoot and may well be pardoned if he mistakes rabbits for tigers, eagles for barndoor fowls, or misses altogether and wastes his shot upon some peaceful cow grazing in a further field. If behind the erratic gunfire of the press the author felt that there was another kind of criticism, the opinion of people reading for the love of reading, slowly and unprofessionally, and judging with great sympathy and yet with great severity, might this not improve the quality of his work? And if by our means books were to become stronger, richer, and more varied, that would be an end worth reaching.

Yet who reads to bring about an end, however desirable? Are there not some pursuits that we practice because they are good in themselves, and some pleasures that are final? And is not this among them? I have sometimes dreamt, at least that when the Day of judgment dawns and the great conquerors and lawyers and statesmen come to receive their rewards—their crowns, their laurels, their names carved indelibly upon imperishable marble—the Almighty will turn to Peter and will say, not without a certain envy when He sees us coming with our books under our arms, “Look, these need no reward. We have nothing to give them here. They have loved reading.”

Virgina Woolf

(The Common Reader, Second Series 1926)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Libraries in Literature, The Art of Reading, Woolf, Virginia

Hans Warren

(1921-2001)

Terugkeer

We liepen door het late land. De bomen

geurden bedwelmend en de zomerlucht was zwaar.

Duister schoof over vers gemaaide klaver.

De wind kwam als een warm en tastbaar aaien

onder de hemel, spiegelend in een meer

op blauwgroen fond zijn ambergele wolkenvlokken.

Er klonk vreemde muziek, die ik vergat.

We zagen achter wijde velden spitse torens,

gerezen aan de duistere einderboog

tegen het stil verschilferd koepelparelmoer.

Er was gefluister en gegiechel langs de wegen

en bladerschaduw als een lokkend grottenhol.

Terugkeer. Dit nooit kunnen verwoorden:

terugkeer door de zomeravond, naar huis,

maar niet mijn huis, het onvolmaakte.

Dit was nóóit samen, altijd heel alleen,

de lucht moest warmer zijn dan bloed,

het licht heel rood verguld, de geuren

bijna verstikkend zwaar. Een ander paar

moest ergens dwalen, een veel gelukkiger

en mooier paar, en een jonge landman zong

of oefende in een tuin op een trombone.

En nooit heb ik dat huis bereikt, maar soms

in dromen ben ik nog op weg daarheen.

![]()

(Uit: Hans Warren: ‘Verzamelde gedichten’, Amsterdam 2002)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X

![]()

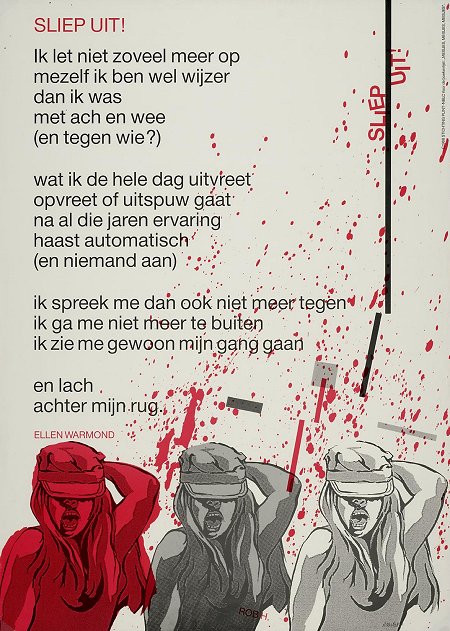

De dichteres Ellen Warmond (pseudoniem van Pietronella Cornelia van Yperen) is, na een lang ziekbed, op 28 juni 2011 overleden. Naast haar dichtwerk (debuut: Proeftuin 1953), schreef ze veel secundaire literatuur, zoals biografieën van o.a. Louis Couperus, Herman Gorter, Adriaan Roland Holst, E. du Perron en Anna Blaman.

Ellen Warmond

(1930-2011)

Jong als kinderstemmen

Jong als kinderstemmen

reeds met de tongval van de ouderdom

te kunnen zeggen:

zie achter mij hoeveel ik al tot stof geleefd heb

en hoeveel as zich ophoopt in mijn ogen

en hoeveel stof en as mijn hand daarvan

bevatten kan en samenbalt tot niets.

en toch en desondanks

wachten – onmatig –

– want matigheid is zwakte –

en nieuwe kleren kopen voor de hoop

hoewel de laatste zekerheden naakt gaan

en trachten waar men niet bestond

toch te ontstaan

om het onmogelijk natuurverschijnsel:

zon in de maan

rondlopende weg terug

of het oog in de rug.

omdat geloof ontspringt

uit de zekerheid dat er geen hoop meer is

omdat het hart zich voedt

met wat de hand ontvalt.

Ellen Warmond (1930-2011) gedichten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, In Memoriam

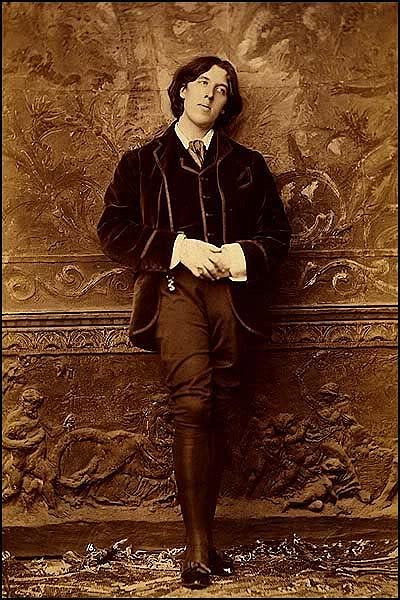

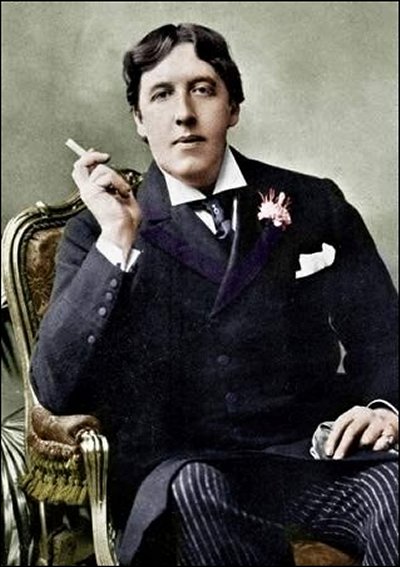

Oscar Wilde

(1854-1900)

Requiescat

Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow,

Speak gently, she can hear

The daisies grow.

All her bright golden hair

Tarnished with rust,

She that was young and fair

Fallen to dust.

Lily-like, white as snow,

She hardly knew

She was a woman, so

Sweetly she grew.

Coffin-board, heavy stone,

Lie on her breast,

I vex my heart alone

She is at rest.

Peace, Peace, she cannot hear

Lyre or sonnet,

All my life’s buried here,

Heap earth upon it.

Avignon

Oscar Wilde

Dat zij rusten mag

Stap zachtjes, zij is dichtbij,

Sneeuw ligt op haar,

Spreek teer, reeds groeit – hoort zij –

‘t Meizoentje daar.

Zij, nog zo jong, gezond

Daalde tot stof,

Lokken zo glanzend blond

Dor nu en dof.

‘n Lelie gelijk, sneeuwwit,

Ging haar voorbij

‘t Vrouw-zijn als haar bezit,

Zo zoet werd zij.

Kistdeksel, zware steen,

Drukken op haar,

Ik terg mijn hart alleen

Zij rust nu daar.

Zij hoort ode noch lier,

Stil nu, O stop,

Heel mijn leven ligt hier,

Schep aarde er op.

Vertaling Cornelis W. Schoneveld

Oscar Wilde: Requiescat

Dit gedicht herdenkt Wilde’s 3 jaar jongere zusje Isola die stierf in de winter van 1867 toen Oscar 12 jaar oud was. Wilde bezocht Avignon op zijn reis naar Italië in 1875.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Wilde, Oscar

Oscar Wilde

(1854-1900)

Impression Du Matin

The Thames nocturne of blue and gold

Changed to a Harmony in grey:

A barge with ochre-coloured hay

Dropt from the wharf: and chill and cold

The yellow fog came creeping down

The bridges, till the houses’ walls

Seemed changed to shadows, and S. Paul’s

Loomed like a bubble o’er the town.

Then suddenly arose the clang

Of waking life; the streets were stirred

With country waggons: and a bird

Flew to the glistening roofs and sang.

But one pale woman all alone,

The daylight kissing her wan hair,

Loitered beneath the gas lamps’ flare,

With lips of flame and heart of stone.

Oscar Wilde

Indruk van de ochtend

De Theems nocturne in blauw en goud

Werd tot een harmonie in grijs;

Een hooibark stak van wal op reis,

Oker van kleur: en kil en koud

Zocht van de bruggen af zijn pad

De gele mist, tot overal

Steen slechts een schim leek, en als ‘n bal

St. Paul’s hoog oprees uit de stad.

Wat dan ineens veel drukte bood

Was ‘t opstaan; ‘n koetsenrij bewoog

Zich voort door elke straat; er vloog

Een vogel ‘t glansdak op en floot.

Maar ‘n bleke vrouw geheel alleen,

Een dagglimp op haar vaal gezicht,

Liep talmend voort bij ‘t gaslamplicht,

De lip in vlam en ‘t hart van steen.

Vertaling Cornelis W. Schoneveld

Oscar Wilde: Impression Du Matin

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, London Poems, Wilde, Wilde, Oscar

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

Together and Apart

Mrs. Dalloway introduced them, saying you will like him. The conversation began some minutes before anything was said, for both Mr. Serle and Miss Arming looked at the sky and in both of their minds the sky went on pouring its meaning though very differently, until the presence of Mr. Serle by her side became so distinct to Miss Anning that she could not see the sky, simply, itself, any more, but the sky shored up by the tall body, dark eyes, grey hair, clasped hands, the stern melancholy (but she had been told “falsely melancholy”) face of Roderick Serle, and, knowing how foolish it was, she yet felt impelled to say:

“What a beautiful night!”

Foolish! Idiotically foolish! But if one mayn’t be foolish at the age of forty in the presence of the sky, which makes the wisest imbecile—mere wisps of straw—she and Mr. Serle atoms, motes, standing there at Mrs. Dalloway’s window, and their lives, seen by moonlight, as long as an insect’s and no more important.

“Well!” said Miss Anning, patting the sofa cushion emphatically. And down he sat beside her. Was he “falsely melancholy,” as they said? Prompted by the sky, which seemed to make it all a little futile—what they said, what they did—she said something perfectly commonplace again:

“There was a Miss Serle who lived at Canterbury when I was a girl there.”

With the sky in his mind, all the tombs of his ancestors immediately appeared to Mr. Serle in a blue romantic light, and his eyes expanding and darkening, he said: “Yes.

“We are originally a Norman family, who came over with the Conqueror. That is a Richard Serle buried in the Cathedral. He was a knight of the garter.”

Miss Arming felt that she had struck accidentally the true man, upon whom the false man was built. Under the influence of the moon (the moon which symbolized man to her, she could see it through a chink of the curtain, and she took dips of the moon) she was capable of saying almost anything and she settled in to disinter the true man who was buried under the false, saying to herself: “On, Stanley, on”—which was a watchword of hers, a secret spur, or scourge such as middle–aged people often make to flagellate some inveterate vice, hers being a deplorable timidity, or rather indolence, for it was not so much that she lacked courage, but lacked energy, especially in talking to men, who frightened her rather, and so often her talks petered out into dull commonplaces, and she had very few men friends—very few intimate friends at all, she thought, but after all, did she want them? No. She had Sarah, Arthur, the cottage, the chow and, of course THAT, she thought, dipping herself, sousing herself, even as she sat on the sofa beside Mr. Serle, in THAT, in the sense she had coming home of something collected there, a cluster of miracles, which she could not believe other people had (since it was she only who had Arthur, Sarah, the cottage, and the chow), but she soused herself again in the deep satisfactory possession, feeling that what with this and the moon (music that was, the moon), she could afford to leave this man and that pride of his in the Serles buried. No! That was the danger—she must not sink into torpidity—not at her age. “On, Stanley, on,” she said to herself, and asked him:

“Do you know Canterbury yourself?”

Did he know Canterbury! Mr. Serle smiled, thinking how absurd a question it was—how little she knew, this nice quiet woman who played some instrument and seemed intelligent and had good eyes, and was wearing a very nice old necklace—knew what it meant. To be asked if he knew Canterbury. When the best years of his life, all his memories, things he had never been able to tell anybody, but had tried to write—ah, had tried to write (and he sighed) all had centred in Canterbury; it made him laugh.

His sigh and then his laugh, his melancholy and his humour, made people like him, and he knew it, and vet being liked had not made up for the disappointment, and if he sponged on the liking people had for him (paying long calls on sympathetic ladies, long, long calls), it was half bitterly, for he had never done a tenth part of what he could have done, and had dreamed of doing, as a boy in Canterbury. With a stranger he felt a renewal of hope because they could not say that he had not done what he had promised, and yielding to his charm would give him a fresh startat fifty! She had touched the spring. Fields and flowers and grey buildings dripped down into his mind, formed silver drops on the gaunt, dark walls of his mind and dripped down. With such an image his poems often began. He felt the desire to make images now, sitting by this quiet woman.

“Yes, I know Canterbury,” he said reminiscently, sentimentally, inviting, Miss Anning felt, discreet questions, and that was what made him interesting to so many people, and it was this extraordinary facility and responsiveness to talk on his part that had been his undoing, so he thought often, taking his studs out and putting his keys and small change on the dressing–table after one of these parties (and he went out sometimes almost every night in the season), and, going down to breakfast, becoming quite different, grumpy, unpleasant at breakfast to his wife, who was an invalid, and never went out, but had old friends to see her sometimes, women friends for the most part, interested in Indian philosophy and different cures and different doctors, which Roderick Serle snubbed off by some caustic remark too clever for her to meet, except by gentle expostulations and a tear or two—he had failed, he often thought, because he could not cut himself off utterly from society and the company of women, which was so necessary to him, and write. He had involved himself too deep in life—and here he would cross his knees (all his movements were a little unconventional and distinguished) and not blame himself, but put the blame off upon the richness of his nature, which he compared favourably with Wordsworth’s, for example, and, since he had given so much to people, he felt, resting his head on his hands, they in their turn should help him, and this was the prelude, tremulous, fascinating, exciting, to talk; and images bubbled up in his mind.

“She’s like a fruit tree—like a flowering cherry tree,” he said, looking at a youngish woman with fine white hair. It was a nice sort of image, Ruth Anning thought—rather nice, yet she did not feel sure that she liked this distinguished, melancholy man with his gestures; and it’s odd, she thought, how one’s feelings are influenced. She did not like HIM, though she rather liked that comparison of his of a woman to a cherry tree. Fibres of her were floated capriciously this way and that, like the tentacles of a sea anemone, now thrilled, now snubbed, and her brain, miles away, cool and distant, up in the air, received messages which it would sum up in time so that, when people talked about Roderick Serle (and he was a bit of a figure) she would say unhesitatingly: “I like him,” or “I don’t like him,” and her opinion would be made up for ever. An odd thought; a solemn thought; throwing a green light on what human fellowship consisted of.

“It’s odd that you should know Canterbury,” said Mr. Serle. “It’s always a shock,” he went on (the white–haired lady having passed), “when one meets someone” (they had never met before), “by chance, as it were, who touches the fringe of what has meant a great deal to oneself, touches accidentally, for I suppose Canterbury was nothing but a nice old town to you. So you stayed there one summer with an aunt?” (That was all Ruth Anning was going to tell him about her visit to Canterbury.) “And you saw the sights and went away and never thought of it again.”

Let him think so; not liking him, she wanted him to run away with an absurd idea of her. For really, her three months in Canterbury had been amazing. She remembered to the last detail, though it was merely a chance visit, going to see Miss Charlotte Serle, an acquaintance of her aunt’s. Even now she could repeat Miss Serle’s very words about the thunder. “Whenever I wake, or hear thunder in the night, I think ‘Someone has been killed’.” And she could see the hard, hairy, diamond–patterned carpet, and the twinkling, suffused, brown eyes of the elderly lady, holding the teacup out unfilled, while she said that about the thunder. And always she saw Canterbury, all thundercloud and livid apple blossom, and the long grey backs of the buildings.

The thunder roused her from her plethoric middleaged swoon of indifference; “On, Stanley, on,” she said to herself; that is, this man shall not glide away from me, like everybody else, on this false assumption; I will tell him the truth.

“I loved Canterbury,” she said.

He kindled instantly. It was his gift, his fault, his destiny.

“Loved it,” he repeated. “I can see that you did.”

Her tentacles sent back the message that Roderick Serle was nice.

Their eyes met; collided rather, for each felt that behind the eyes the secluded being, who sits in darkness while his shallow agile companion does all the tumbling and beckoning, and keeps the show going, suddenly stood erect; flung off his cloak; confronted the other. It was alarming; it was terrific. They were elderly and burnished into a glowing smoothness, so that Roderick Serle would go, perhaps to a dozen parties in a season, and feel nothing out of the common, or only sentimental regrets, and the desire for pretty images—like this of the flowering cherry tree—and all the time there stagnated in him unstirred a sort of superiority to his company, a sense of untapped resources, which sent him back home dissatisfied with life, with himself, yawning, empty, capricious. But now, quite suddenly, like a white bolt in a mist (but this image forged itself with the inevitability of lightning and loomed up), there it had happened; the old ecstasy of life; its invincible assault; for it was unpleasant, at the same time that it rejoiced and rejuvenated and filled the veins and nerves with threads of ice and fire; it was terrifying. “Canterbury twenty years ago,” said Miss Anning, as one lays a shade over an intense light, or covers some burning peach with a green leaf, for it is too strong, too ripe, too full.

Sometimes she wished she had married. Sometimes the cool peace of middle life, with its automatic devices for shielding mind and body from bruises, seemed to her, compared with the thunder and the livid appleblossom of Canterbury, base. She could imagine something different, more like lightning, more intense. She could imagine some physical sensation. She could imagine——

And, strangely enough, for she had never seen him before, her senses, those tentacles which were thrilled and snubbed, now sent no more messages, now lay quiescent, as if she and Mr. Serle knew each other so perfectly, were, in fact, so closely united that they had only to float side by side down this stream.

Of all things, nothing is so strange as human intercourse, she thought, because of its changes, its extraordinary irrationality, her dislike being now nothing short of the most intense and rapturous love, but directly the word “love” occurred to her, she rejected it, thinking again how obscure the mind was, with its very few words for all these astonishing perceptions, these alternations of pain and pleasure. For how did one name this. That is what she felt now, the withdrawal of human affection, Serle’s disappearance, and the instant need they were both under to cover up what was so desolating and degrading to human nature that everyone tried to bury it decently from sight—this withdrawal, this violation of trust, and, seeking some decent acknowledged and accepted burial form, she said:

“Of course, whatever they may do, they can’t spoil Canterbury.”

He smiled; he accepted it; he crossed his knees the other way about. She did her part; he his. So things came to an end. And over them both came instantly that paralysing blankness of feeling, when nothing bursts from the mind, when its walls appear like slate; when vacancy almost hurts, and the eyes petrified and fixed see the same spot—a pattern, a coal scuttle—with an exactness which is terrifying, since no emotion, no idea, no impression of any kind comes to change it, to modify it, to embellish it, since the fountains of feeling seem sealed and as the mind turns rigid, so does the body; stark, statuesque, so that neither Mr. Serle nor Miss Anning could move or speak, and they felt as if an enchanter had freed them, and spring flushed every vein with streams of life, when Mira Cartwright, tapping Mr. Serle archly on the shoulder, said:

“I saw you at the Meistersinger, and you cut me. Villain,” said Miss Cartwright, “you don’t deserve that I should ever speak to you again.”

And they could separate.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: A Haunted House, and other short stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

O s c a r W i l d e

(1854-1900)

Requiescat

Tread lightly, she is near

Under the snow,

Speak gently, she can hear

The daisies grow.

All her bright golden hair

Tarnished with rust,

She that was young and fair

Fallen to dust.

Lily-like, white as snow,

She hardly knew

She was a woman, so

Sweetly she grew.

Coffin-board, heavy stone,

Lie on her breast,

I vex my heart alone,

She is at rest.

Peace, Peace, she cannot hear

Lyre or sonnet,

All my life’s buried here,

Heap earth upon it.

.jpg)

Oscar Wilde poetry

k e m p i s . n l p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar

![]()

Frank Wedekind

(1864-1918)

Menschlichkeit

Der grausamste Krieg – der menschlichste Krieg!

Zum Frieden führt er durch raschesten Sieg.

Kaum hört’s der Gegner, denkt er: Hallo!

Natürlich wüt’ ich dann ebenso!

Nun treiben die beiden Wüteriche

Die Grausamkeit ins Ungeheuerliche

Und suchen durch das grausamste Wüten

Sich gegenseitig zu überbieten –

Jeder gegen den andern bewehrt

Durch zehn Millionen Leute,

Und wenn sie noch nicht aufgehört,

Dann wüten sie noch heute.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Frank Wedekind

Jacqueline E. van der Waals

(1868-1922)

Melancolia

Toen ik door het maanlicht liep

En de paden meed,

Bang, dat ik den tuin, die sliep,

Wakkerschrikken deed

Door het ritselend gerucht

Van mijn kleed en voet –

De oude boomen! die een zucht

Wakkerschrikken doet.

Toen ik naar den vijver ging

Door het korte gras,

Naar den boom die overhing

In den vijverplas,

Waar het water inkt geleek,

En zo roerloos sliep,

Of het oog in ‘t duister keek

Van een peilloos diep,

Waar het windgefluister klonk

Door het popelblad…

Weet gij, wie op d’ elzentronk

Mij te wachten zat?

Vleermuisvleugelige vrouw,

Die mij eeuwig jong,

‘t Eeuwig oude lied van rouw

Vaak te voren zong,

Tot ik in den maneschijn

Zacht heb meegeschreid

Met het eeuwenoud refrein:

“Alles ijdelheid.”

Hebt ge hier op mij gewacht,

Denkend, dat ik sliep?

Hebt gij zóó aan mij gedacht,

Dat uw geest mij riep,

Dat ik staan kwam aan het raam

En onrustig werd

Door het roepen van mijn naam

Uit de lichte vert’?….

Toen ik u hier wachten vond

En met stillen schrik

In den peilloos diepen grond

Staarde van uw blik,

Toen ik zwijgend binnentrad

En in zwarte schauw

Uwer vleuglen nederzat,

Zwartgewiekte vrouw,

Heb ik, met uw hoofd gevleid,

Liefste aan mijn hart,

Zachtkens met u meê geschreid

Om der dingen ijdelheid

Om onze oude smart.

Jacqueline E. van der Waals gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Waals, Jacqueline van der

![]()

Mathilde Wesendonck

(1828 – 1902)

5 Lieder

Lied 1: Der Engel

In der Kindheit frühen Tagen

Hört ich oft von Engeln sagen,

Die des Himmels hehre Wonne

Tauschen mit der Erdensonne,

Daß, wo bang ein Herz in Sorgen

Schmachtet vor der Welt verborgen,

Daß, wo still es will verbluten,

Und vergehn in Tränenfluten,

Daß, wo brünstig sein Gebet

Einzig um Erlösung fleht,

Da der Engel niederschwebt,

Und es sanft gen Himmel hebt.

Ja, es stieg auch mir ein Engel nieder,

Und auf leuchtendem Gefieder

Führt er, ferne jedem Schmerz,

Meinen Geist nun himmelwärts!

Lied 2: Stehe still!

Sausendes, brausendes Rad der Zeit,

Messer du der Ewigkeit;

Leuchtende Sphären im weiten All,

Die ihr umringt den Weltenball;

Urewige Schöpfung, halte doch ein,

Genug des Werdens, laß mich sein!

Halte an dich, zeugende Kraft,

Urgedanke, der ewig schafft!

Hemmet den Atem, stillet den Drang,

Schweiget nur eine Sekunde lang!

Schwellende Pulse, fesselt den Schlag;

Ende, des Wollens ew’ger Tag!

Daß in selig süßem Vergessen

Ich mög alle Wonnen ermessen!

Wenn Aug’ in Auge wonnig trinken,

Seele ganz in Seele versinken;

Wesen in Wesen sich wiederfindet,

Und alles Hoffens Ende sich kündet,

Die Lippe verstummt in staunendem Schweigen,

Keinen Wunsch mehr will das Innre zeugen:

Erkennt der Mensch des Ew’gen Spur,

Und löst dein Rätsel, heil’ge Natur!

Lied 3: Im Treibhaus

Hochgewölbte Blätterkronen,

Baldachine von Smaragd,

Kinder ihr aus fernen Zonen,

Saget mir, warum ihr klagt?

Schweigend neiget ihr die Zweige,

Malet Zeichen in die Luft,

Und der Leiden stummer Zeuge

Steiget aufwärts, süßer Duft.

Weit in sehnendem Verlangen

Breitet ihr die Arme aus,

Und umschlinget wahnbefangen

Öder Leere nicht’gen Graus.

Wohl, ich weiß es, arme Pflanze;

Ein Geschicke teilen wir,

Ob umstrahlt von Licht und Glanze,

Unsre Heimat ist nicht hier!

Und wie froh die Sonne scheidet

Von des Tages leerem Schein,

Hüllet der, der wahrhaft leidet,

Sich in Schweigens Dunkel ein.

Stille wird’s, ein säuselnd Weben

Füllet bang den dunklen Raum:

Schwere Tropfen seh ich schweben

An der Blätter grünem Saum.

Lied 4: Schmerzen

Sonne, weinest jeden Abend

Dir die schönen Augen rot,

Wenn im Meeresspiegel badend

Dich erreicht der frühe Tod;

Doch erstehst in alter Pracht,

Glorie der düstren Welt,

Du am Morgen neu erwacht,

Wie ein stolzer Siegesheld!

Ach, wie sollte ich da klagen,

Wie, mein Herz, so schwer dich sehn,

Muß die Sonne selbst verzagen,

Muß die Sonne untergehn?

Und gebieret Tod nur Leben,

Geben Schmerzen Wonne nur:

O wie dank ich, daß gegeben

Solche Schmerzen mir Natur!

Lied 5: Träume

Sag, welch wunderbare Träume

Halten meinen Sinn umfangen,

Daß sie nicht wie leere Schäume

Sind in ödes Nichts vergangen?

Träume, die in jeder Stunde,

Jedem Tage schöner blühn,

Und mit ihrer Himmelskunde

Selig durchs Gemüte ziehn!

Träume, die wie hehre Strahlen

In die Seele sich versenken,

Dort ein ewig Bild zu malen:

Allvergessen, Eingedenken!

Träume, wie wenn Frühlingssonne

Aus dem Schnee die Blüten küßt,

Daß zu nie geahnter Wonne

Sie der neue Tag begrüßt,

Daß sie wachsen, daß sie blühen,

Träumed spenden ihren Duft,

Sanft an deiner Brust verglühen,

Und dann sinken in die Gruft.

(1857-1858 Von Wagner komponiert)

Mathilde Wesendonck poetry

Poem of the week June 20, 2010

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X

foto jefvankempen

In Memoriam Driek van Wissen (1943-2010)

Driek van Wissen werd in 1943 geboren in de stad Groningen, waar hij nog steeds woonachtig was. Hij studeerde er Nederlands aan de Rijksuniversiteit en van 1968 tot 2005 was hij werkzaam als docent Nederlands aan het Dr. Aletta Jacobs College te Hoogezand. Van 1975 tot 1977 was hij redacteur van het Groningse tijdschrift “De Nieuwe Clercke”. Vanaf 1976 verschenen bundels van zijn hand bij verschillende uitgeverijen.

Driek van Wissen was een vormvast dichter. Hij schreef onder meer kwatrijnen, rondelen en ollekebollekes, maar het sonnet had zijn bijzondere voorkeur. Zijn gedichten zijn over het algemeen vrij luchtig van toon, hij wordt dan ook meestal tot de light-verse-dichters gerekend. In 1987 werd Driek van Wissen onderscheiden met de Kees Stip Prijs voor light verse.

In 2005 werd Van Wissen verkozen tot Dichter des Vaderlands als opvolger van Gerrit Komrij. In 2009 werd hij opgevolgd door Ramsey Nasr.

Driek van Wissen overleed op 20 mei 2010 op 66-jarige leeftijd in Istanbul aan de gevolgen van een hersenbloeding.

Moeder en kind

Mijn moeder leefde voor zichzelf te lang;

Vandaar dat zij haar laatste grijze dagen

Veelal verdeed met mopperen en klagen,

Een vruchteloze, zure zwanenzang.

Toch schepte zij een kinderlijk behagen

In onze dagelijkse ommegang

Als ik weg uit het huis, uit haar gevang

Haar rondreed in haar invalidenwagen.

De vreugde was niet altijd onverdeeld:

Ik deed het half uit liefde, half verveeld,

Maar ik kwam in het park soms halverwege

Een moeder met een kinderwagen tegen

En zag dan het verdraaide spiegelbeeld

Hoe ik ooit in haar wagen had gelegen.

Driek van Wissen, uit: Voor het vaderland weg, 2009

Photo: kemp=mag 2005

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, City Poets / Stadsdichters, LIGHT VERSE

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature