Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Sick I am and sorrowful

Sick I am and sorrowful, how can I be well again

Here, where fog and darkness are, and big guns boom all day,

Practising for evil sport? If you speak humanity,

Hatred comes into each face, and so you cease to pray.

How I dread the sound of guns, hate the bark of musketry,

Since the friends I loved are dead, all stricken by the sword.

Full of anger is my heart, full of rage and misery;

How can I grow well again, or be my peace restored?

If I were in Glenmalure, or in Enniskerry now,

Hearing of the coming spring in the pinetree’s song;

If I woke on Arran Strand, dreamt me on the cliffs of Moher,

Could I not grow gay again, should I not be strong?

If I stood with eager heart on the heights of Carrantuohill,

Beaten by the four great winds into hope and joy again,

Far above the cannons’ roar or the scream of musketry,

If I heard the four great seas, what were weariness or pain?

Were I in a little town, Ballybunion, Ballybrack,

Laughing with the children there, I would sing and dance once more,

Heard again the storm clouds roll hanging over Lugnaquilla,

Built dream castles from the sands of Killiney’s golden shore.

If I saw the wild geese fly over the dark lakes of Kerry

Or could hear the secret winds, I could kneel and pray.

But ’tis sick I am and grieving, how can I be well again

Here, where fear and sorrow are—my heart so far away?

Dora Maria Sigerson Shorter

(1866 – 1918)

Sick I am and sorrowful

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Sigerson Shorter, Dora Maria, WAR & PEACE

O! there are spirits of the air

O! there are spirits of the air

And genii of the evening breeze,

And gentle ghosts, with eyes as fair

As star-beams among twilight trees:—

Such lovely ministers to meet

Oft hast thou turned from men thy lonely feet.

With mountain winds, and babbling springs,

And moonlight seas, that are the voice

Of these inexplicable things

Thou didst hold commune, and rejoice

When they did answer thee; but they

Cast, like a worthless boon, thy love away.

And thou hast sought in starry eyes

Beams that were never meant for thine

Another’s wealth:—tame sacrifice

To a fond faith I still dost thou pine!

Still dost thou hope that greeting hands,

Voice, looks, or lips, may answer thy demands!

Ah! wherefore didst thou build thine hope

On the false earth’s inconstancy!

Did thine own, mind afford no scope

Of love, or moving thoughts to thee!

That natural scenes or human smiles

Could steal the power to wind thee in their wiles.

Yes, all the faithless smiles are fled

Whose falsehood left thee broken-hearted;

The glory of the moon is dead;

Night’s ghosts and dreams have now departed;

Thine own soul still is true to thee,

But changed to a foul fiend through misery.

This fiend, whose ghastly presence ever

Beside thee like thy shadow hangs,

Dream not to chase;—the mad endeavour

Would scourge thee to severer pangs.

Be as thou art. Thy settled fate,

Dark as it is, all change would aggravate.

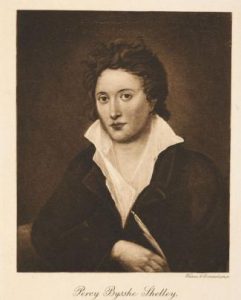

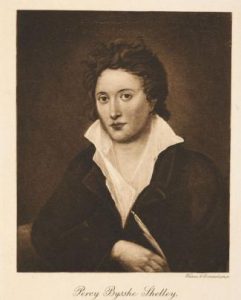

Percy Bysshe Shelley

(1792 – 1822)

O! there are spirits of the air

1886

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Classic Poetry Archive, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Shelley, Percy Byssche

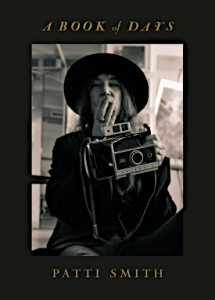

A deeply moving and brilliantly idiosyncratic visual book of days by the National Book Awardwinning author of Just Kids and M Train, featuring more than 365 images and reflections that chart Smiths singular aestheticinspired by her wildly popular Instagram.

In 2018, without any plan or agenda for what might happen next, Patti Smith posted her first Instagram photo: her hand with the simple message Hello Everybody! Known for shooting with her beloved Land Camera 250, Smith started posting images from her phone including portraits of her kids, her radiator, her boots, and her Abyssinian cat, Cairo.

In 2018, without any plan or agenda for what might happen next, Patti Smith posted her first Instagram photo: her hand with the simple message Hello Everybody! Known for shooting with her beloved Land Camera 250, Smith started posting images from her phone including portraits of her kids, her radiator, her boots, and her Abyssinian cat, Cairo.

Followers felt an immediate affinity with these miniature windows into Smiths world, photographs of her daily coffee, the books shes reading, the graves of beloved heroes William Blake, Dylan Thomas, Sylvia Plath, Simone Weil, Albert Camus. Over time, a coherent story of a life devoted to art took shape, and more than a million followers responded to Smiths unique aesthetic in images that chart her passions, devotions, obsessions, and whims.

Original to this book are vintage photographs: anniversary pearls, a mothers keychain, and a husbands Mosrite guitar. Here, too, are photos from Smiths archives of life on and off the road, train stations, obscure cafés, a notebook always nearby. In wide-ranging yet intimate daily notations, Smith shares dispatches from her travels around the world.

With over 365 photographs taking you through a single year, A Book of Days is a new way to experience the expansive mind of the visionary poet, writer, and performer. Hopeful, elegiac, playfuland complete with an introduction by Smith that explores her documentary processA Book of Days is a timeless offering for deeply uncertain times, an inspirational map of an artists life.

Patti Smith is a writer, performer, and visual artist. She gained recognition in the 1970s for her revolutionary merging of poetry and rock. She has released twelve albums, including Horses, which has been hailed as one of the top one hundred debut albums of all time by Rolling Stone.

Smith had her first exhibit of drawings at the Gotham Book Mart in 1973 and has been represented by the Robert Miller Gallery since 1978. Her books include Just Kids, winner of the National Book Award in 2010, Wītt, Babel, Woolgathering, The Coral Sea, and Auguries of Innocence.

A Book of Days Hardcover

by Patti Smith

Language: English

Publication date: 11/15/2022

Publisher: Random House Publishing Group

ISBN-10: 0593448545

ISBN-13: 978-0593448540

Pages: 400

Hardcover

$22.99

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Patti Smith, Photography, Smith, Patti

Schwangeres Mädchen

Du schreitest wunderbar in mittaglicher Stunde,

Um Deine Brüste rauscht der reife Wind,

Ein Lichtbach über Deinen Nacken rinnt,

Der Sommer blüht auf Deinem Munde.

Du bist ein Wunderkelch der gnadenreichen

Empfängnis liebestrunkner Nacht,

Du bist von Lerchenliedern überdacht,

Und Deine Last ist köstlich ohnegleichen.

Ernst Toller

(1893 – 1939)

Schwangeres Mädchen

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Toller, Ernst

Loud Shout

The Flaming Tongues of war

Ta’n Sionac Ar Sraidib Ag Faire Go Caocrac

Air—“The West’s Asleep.”

Loud shout the flaming tongues of war.

The cannon’s thunder rolls afar

While Empires tremble for their fall.

Thou art alone amongst them all.

Where is the friend who for thy sake

Will on his sword thy freedom take?

The son who holds thy right alone

Above an Empire or a throne?

Ah, Grannia Wael, thy stricken head

Is bowed in sorrow o’er thy dead,

Thy dead who died for love of thee,

Not for some foreign liberty.

Shall we betray when hope is near,

Our Motherland whom we hold dear,

To go to fight on foreign strand,

For foreign rights and foreign land?

The Lion’s fangs have sought to kill

A Nation’s soul, a Nation’s will;

From tooth and claw thy wounded breast

Has held them safe, has held them blest.

About thy head great eagles are,

They fly with scream and storm of war,

Their shadows fall, we do not know

If they be friend,—if they be foe.

For Lion’s roar we have no fears,

We fought him down the restless years.

We watch the Eagles in the sky,

Lest they should land—or pass us by.

But, yet beware! the Lion goes

To strike our friends—to charm our foes.

By hamlet small, by hill and dale

The creeping foe is on our trail;

His face is kind, his voice is bland,

He prates of faith and fatherland;

Shall we go forth to die and die

For Belgium’s tear, and Serbia’s sigh?

Oh, Volunteers, through field and town

He seeks his prey, he tracks thee down

His voice is soft, his words are fair,

It is the creeping foe, Beware!

Ah, Grannia Wael, in blood and tears

We fought thy battles through the years,

That thou shouldst live we’re glad to die

In prison cell or gallows high.

Oh, cursed be he ! who to our shame

Drives forth thy manhood in thy name,

O, WHILE THE LION LAPS YOUR BLOOD

SHALL WE UNITE IN SERVITUDE.

Dora Maria Sigerson Shorter

(1866 – 1918)

Loud Shout The Flaming Tongues of war

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Sigerson Shorter, Dora Maria, WAR & PEACE

The Cloud

I bring fresh showers for the thirsting flowers,

From the seas and the streams;

I bear light shade for the leaves when laid

In their noonday dreams.

From my wings are shaken the dews that waken

The sweet buds every one,

When rocked to rest on their mother’s breast,

As she dances about the sun.

I wield the flail of the lashing hail,

And whiten the green plains under,

And then again I dissolve it in rain,

And laugh as I pass in thunder.

I sift the snow on the mountains below,

And their great pines groan aghast;

And all the night ’tis my pillow white,

While I sleep in the arms of the blast.

Sublime on the towers of my skiey bowers,

Lightning my pilot sits;

In a cavern under is fettered the thunder,

It struggles and howls at fits;

Over earth and ocean, with gentle motion,

This pilot is guiding me,

Lured by the love of the genii that move

In the depths of the purple sea;

Over the rills, and the crags, and the hills,

Over the lakes and the plains,

Wherever he dream, under mountain or stream,

The Spirit he loves remains;

And I all the while bask in Heaven’s blue smile,

Whilst he is dissolving in rains.

The sanguine Sunrise, with his meteor eyes,

And his burning plumes outspread,

Leaps on the back of my sailing rack,

When the morning star shines dead;

As on the jag of a mountain crag,

Which an earthquake rocks and swings,

An eagle alit one moment may sit

In the light of its golden wings.

And when Sunset may breathe, from the lit sea beneath,

Its ardours of rest and of love,

And the crimson pall of eve may fall

From the depth of Heaven above,

With wings folded I rest, on mine aëry nest,

As still as a brooding dove.

That orbèd maiden with white fire laden,

Whom mortals call the Moon,

Glides glimmering o’er my fleece-like floor,

By the midnight breezes strewn;

And wherever the beat of her unseen feet,

Which only the angels hear,

May have broken the woof of my tent’s thin roof,

The stars peep behind her and peer;

And I laugh to see them whirl and flee,

Like a swarm of golden bees,

When I widen the rent in my wind-built tent,

Till calm the rivers, lakes, and seas,

Like strips of the sky fallen through me on high,

Are each paved with the moon and these.

I bind the Sun’s throne with a burning zone,

And the Moon’s with a girdle of pearl;

The volcanoes are dim, and the stars reel and swim,

When the whirlwinds my banner unfurl.

From cape to cape, with a bridge-like shape,

Over a torrent sea,

Sunbeam-proof, I hang like a roof,

The mountains its columns be.

The triumphal arch through which I march

With hurricane, fire, and snow,

When the Powers of the air are chained to my chair,

Is the million-coloured bow;

The sphere-fire above its soft colours wove,

While the moist Earth was laughing below.

I am the daughter of Earth and Water,

And the nursling of the Sky;

I pass through the pores of the ocean and shores;

I change, but I cannot die.

For after the rain when with never a stain

The pavilion of Heaven is bare,

And the winds and sunbeams with their convex gleams

Build up the blue dome of air,

I silently laugh at my own cenotaph,

And out of the caverns of rain,

Like a child from the womb, like a ghost from the tomb,

I arise and unbuild it again.

Percy Bysshe Shelley

(1792 – 1822)

The Cloud

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Shelley, Percy Byssche

Sixteen Dead Men

Hark! in the still night. Who goes there?

“Fifteen dead men” Why do they wait?

“Hasten, comrade, death is so fair.”

Now comes their Captain through the dim gate.

Sixteen dead men! What on their sword?

“A nation’s honour proud do they bear.”

What on their bent heads? “God’s holy word;

All of their nation’s heart blended in prayer.”

Sixteen dead men! What makes their shroud?

“All of their nation’s love wraps them around.”

Where do their bodies lie, brave and so proud?

“Under the gallows-tree in prison ground.”

Sixteen dead men! Where do they go?

“To join their regiment, where Sarsfield leads;

Wolfe Tone and Emmet, too, well do they know.

There shall they bivouac, telling great deeds.”

Sixteen dead men! Shall they return?

“Yea, they shall come again, breath of our breath.

They on our nation’s hearth made old fires burn.

Guard her unconquered soul, strong in their death.”

Dora Maria Sigerson Shorter

(1866 – 1918)

Sixteen Dead Men

From The Tricolour: Poems of the Irish Revolution (1922)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Sigerson Shorter, Dora Maria, WAR & PEACE

God Sees the Truth, But Waits

by Leo Tolstoy

In the town of Vladimir lived a young merchant named Ivan Dmitrich Aksionov. He had two shops and a house of his own.

Aksionov was a handsome, fair-haired, curly-headed fellow, full of fun, and very fond of singing. When quite a young man he had been given to drink, and was riotous when he had had too much; but after he married he gave up drinking, except now and then.

One summer Aksionov was going to the Nizhny Fair, and as he bade good-bye to his family, his wife said to him, “Ivan Dmitrich, do not start to-day; I have had a bad dream about you.”

Aksionov laughed, and said, “You are afraid that when I get to the fair I shall go on a spree.”

His wife replied: “I do not know what I am afraid of; all I know is that I had a bad dream. I dreamt you returned from the town, and when you took off your cap I saw that your hair was quite grey.”

His wife replied: “I do not know what I am afraid of; all I know is that I had a bad dream. I dreamt you returned from the town, and when you took off your cap I saw that your hair was quite grey.”

Aksionov laughed. “That’s a lucky sign,” said he. “See if I don’t sell out all my goods, and bring you some presents from the fair.”

So he said good-bye to his family, and drove away.

When he had travelled half-way, he met a merchant whom he knew, and they put up at the same inn for the night. They had some tea together, and then went to bed in adjoining rooms.

It was not Aksionov’s habit to sleep late, and, wishing to travel while it was still cool, he aroused his driver before dawn, and told him to put in the horses.

Then he made his way across to the landlord of the inn (who lived in a cottage at the back), paid his bill, and continued his journey.

When he had gone about twenty-five miles, he stopped for the horses to be fed. Aksionov rested awhile in the passage of the inn, then he stepped out into the porch, and, ordering a samovar to be heated, got out his guitar and began to play.

Suddenly a troika drove up with tinkling bells and an official alighted, followed by two soldiers. He came to Aksionov and began to question him, asking him who he was and whence he came. Aksionov answered him fully, and said, “Won’t you have some tea with me?” But the official went on cross-questioning him and asking him. “Where did you spend last night? Were you alone, or with a fellow-merchant? Did you see the other merchant this morning? Why did you leave the inn before dawn?”

Aksionov wondered why he was asked all these questions, but he described all that had happened, and then added, “Why do you cross-question me as if I were a thief or a robber? I am travelling on business of my own, and there is no need to question me.”

Then the official, calling the soldiers, said, “I am the police-officer of this district, and I question you because the merchant with whom you spent last night has been found with his throat cut. We must search your things.”

They entered the house. The soldiers and the police-officer unstrapped Aksionov’s luggage and searched it. Suddenly the officer drew a knife out of a bag, crying, “Whose knife is this?”

Aksionov looked, and seeing a blood-stained knife taken from his bag, he was frightened.

“How is it there is blood on this knife?”

Aksionov tried to answer, but could hardly utter a word, and only stammered: “I–don’t know–not mine.” Then the police-officer said: “This morning the merchant was found in bed with his throat cut. You are the only person who could have done it. The house was locked from inside, and no one else was there. Here is this blood-stained knife in your bag and your face and manner betray you! Tell me how you killed him, and how much money you stole?”

Aksionov swore he had not done it; that he had not seen the merchant after they had had tea together; that he had no money except eight thousand rubles of his own, and that the knife was not his. But his voice was broken, his face pale, and he trembled with fear as though he went guilty.

The police-officer ordered the soldiers to bind Aksionov and to put him in the cart. As they tied his feet together and flung him into the cart, Aksionov crossed himself and wept. His money and goods were taken from him, and he was sent to the nearest town and imprisoned there. Enquiries as to his character were made in Vladimir. The merchants and other inhabitants of that town said that in former days he used to drink and waste his time, but that he was a good man. Then the trial came on: he was charged with murdering a merchant from Ryazan, and robbing him of twenty thousand rubles.

His wife was in despair, and did not know what to believe. Her children were all quite small; one was a baby at her breast. Taking them all with her, she went to the town where her husband was in jail. At first she was not allowed to see him; but after much begging, she obtained permission from the officials, and was taken to him. When she saw her husband in prison-dress and in chains, shut up with thieves and criminals, she fell down, and did not come to her senses for a long time. Then she drew her children to her, and sat down near him. She told him of things at home, and asked about what had happened to him. He told her all, and she asked, “What can we do now?”

“We must petition the Czar not to let an innocent man perish.”

His wife told him that she had sent a petition to the Czar, but it had not been accepted.

Aksionov did not reply, but only looked downcast.

Then his wife said, “It was not for nothing I dreamt your hair had turned grey. You remember? You should not have started that day.” And passing her fingers through his hair, she said: “Vanya dearest, tell your wife the truth; was it not you who did it?”

“So you, too, suspect me!” said Aksionov, and, hiding his face in his hands, he began to weep. Then a soldier came to say that the wife and children must go away; and Aksionov said good-bye to his family for the last time.

When they were gone, Aksionov recalled what had been said, and when he remembered that his wife also had suspected him, he said to himself, “It seems that only God can know the truth; it is to Him alone we must appeal, and from Him alone expect mercy.”

And Aksionov wrote no more petitions; gave up all hope, and only prayed to God.

Aksionov was condemned to be flogged and sent to the mines. So he was flogged with a knot, and when the wounds made by the knot were healed, he was driven to Siberia with other convicts.

For twenty-six years Aksionov lived as a convict in Siberia. His hair turned white as snow, and his beard grew long, thin, and grey. All his mirth went; he stooped; he walked slowly, spoke little, and never laughed, but he often prayed.

In prison Aksionov learnt to make boots, and earned a little money, with which he bought The Lives of the Saints. He read this book when there was light enough in the prison; and on Sundays in the prison-church he read the lessons and sang in the choir; for his voice was still good.

The prison authorities liked Aksionov for his meekness, and his fellow-prisoners respected him: they called him “Grandfather,” and “The Saint.” When they wanted to petition the prison authorities about anything, they always made Aksionov their spokesman, and when there were quarrels among the prisoners they came to him to put things right, and to judge the matter.

No news reached Aksionov from his home, and he did not even know if his wife and children were still alive.

One day a fresh gang of convicts came to the prison. In the evening the old prisoners collected round the new ones and asked them what towns or villages they came from, and what they were sentenced for. Among the rest Aksionov sat down near the newcomers, and listened with downcast air to what was said.

One of the new convicts, a tall, strong man of sixty, with a closely-cropped grey beard, was telling the others what be had been arrested for.

“Well, friends,” he said, “I only took a horse that was tied to a sledge, and I was arrested and accused of stealing. I said I had only taken it to get home quicker, and had then let it go; besides, the driver was a personal friend of mine. So I said, ‘It’s all right.’ ‘No,’ said they, ‘you stole it.’ But how or where I stole it they could not say. I once really did something wrong, and ought by rights to have come here long ago, but that time I was not found out. Now I have been sent here for nothing at all… Eh, but it’s lies I’m telling you; I’ve been to Siberia before, but I did not stay long.”

“Where are you from?” asked some one.

“From Vladimir. My family are of that town. My name is Makar, and they also call me Semyonich.”

Aksionov raised his head and said: “Tell me, Semyonich, do you know anything of the merchants Aksionov of Vladimir? Are they still alive?”

“Know them? Of course I do. The Aksionovs are rich, though their father is in Siberia: a sinner like ourselves, it seems! As for you, Gran’dad, how did you come here?”

Aksionov did not like to speak of his misfortune. He only sighed, and said, “For my sins I have been in prison these twenty-six years.”

“What sins?” asked Makar Semyonich.

But Aksionov only said, “Well, well–I must have deserved it!” He would have said no more, but his companions told the newcomers how Aksionov came to be in Siberia; how some one had killed a merchant, and had put the knife among Aksionov’s things, and Aksionov had been unjustly condemned.

When Makar Semyonich heard this, he looked at Aksionov, slapped his own knee, and exclaimed, “Well, this is wonderful! Really wonderful! But how old you’ve grown, Gran’dad!”

The others asked him why he was so surprised, and where he had seen Aksionov before; but Makar Semyonich did not reply. He only said: “It’s wonderful that we should meet here, lads!”

These words made Aksionov wonder whether this man knew who had killed the merchant; so he said, “Perhaps, Semyonich, you have heard of that affair, or maybe you’ve seen me before?”

“How could I help hearing? The world’s full of rumours. But it’s a long time ago, and I’ve forgotten what I heard.”

“Perhaps you heard who killed the merchant?” asked Aksionov.

Makar Semyonich laughed, and replied: “It must have been him in whose bag the knife was found! If some one else hid the knife there, ‘He’s not a thief till he’s caught,’ as the saying is. How could any one put a knife into your bag while it was under your head? It would surely have woke you up.”

When Aksionov heard these words, he felt sure this was the man who had killed the merchant. He rose and went away. All that night Aksionov lay awake. He felt terribly unhappy, and all sorts of images rose in his mind. There was the image of his wife as she was when he parted from her to go to the fair. He saw her as if she were present; her face and her eyes rose before him; he heard her speak and laugh. Then he saw his children, quite little, as they: were at that time: one with a little cloak on, another at his mother’s breast. And then he remembered himself as he used to be-young and merry. He remembered how he sat playing the guitar in the porch of the inn where he was arrested, and how free from care he had been. He saw, in his mind, the place where he was flogged, the executioner, and the people standing around; the chains, the convicts, all the twenty-six years of his prison life, and his premature old age. The thought of it all made him so wretched that he was ready to kill himself.

“And it’s all that villain’s doing!” thought Aksionov. And his anger was so great against Makar Semyonich that he longed for vengeance, even if he himself should perish for it. He kept repeating prayers all night, but could get no peace. During the day he did not go near Makar Semyonich, nor even look at him.

A fortnight passed in this way. Aksionov could not sleep at night, and was so miserable that he did not know what to do.

One night as he was walking about the prison he noticed some earth that came rolling out from under one of the shelves on which the prisoners slept. He stopped to see what it was. Suddenly Makar Semyonich crept out from under the shelf, and looked up at Aksionov with frightened face. Aksionov tried to pass without looking at him, but Makar seized his hand and told him that he had dug a hole under the wall, getting rid of the earth by putting it into his high-boots, and emptying it out every day on the road when the prisoners were driven to their work.

“Just you keep quiet, old man, and you shall get out too. If you blab, they’ll flog the life out of me, but I will kill you first.”

Aksionov trembled with anger as he looked at his enemy. He drew his hand away, saying, “I have no wish to escape, and you have no need to kill me; you killed me long ago! As to telling of you–I may do so or not, as God shall direct.”

Next day, when the convicts were led out to work, the convoy soldiers noticed that one or other of the prisoners emptied some earth out of his boots. The prison was searched and the tunnel found. The Governor came and questioned all the prisoners to find out who had dug the hole. They all denied any knowledge of it. Those who knew would not betray Makar Semyonich, knowing he would be flogged almost to death. At last the Governor turned to Aksionov whom he knew to be a just man, and said:

“You are a truthful old man; tell me, before God, who dug the hole?”

Makar Semyonich stood as if he were quite unconcerned, looking at the Governor and not so much as glancing at Aksionov. Aksionov’s lips and hands trembled, and for a long time he could not utter a word. He thought, “Why should I screen him who ruined my life? Let him pay for what I have suffered. But if I tell, they will probably flog the life out of him, and maybe I suspect him wrongly. And, after all, what good would it be to me?”

“Well, old man,” repeated the Governor, “tell me the truth: who has been digging under the wall?”

Aksionov glanced at Makar Semyonich, and said, “I cannot say, your honour. It is not God’s will that I should tell! Do what you like with me; I am your hands.”

However much the Governor! tried, Aksionov would say no more, and so the matter had to be left.

That night, when Aksionov was lying on his bed and just beginning to doze, some one came quietly and sat down on his bed. He peered through the darkness and recognised Makar.

“What more do you want of me?” asked Aksionov. “Why have you come here?”

Makar Semyonich was silent. So Aksionov sat up and said, “What do you want? Go away, or I will call the guard!”

Makar Semyonich bent close over Aksionov, and whispered, “Ivan Dmitrich, forgive me!”

“What for?” asked Aksionov.

“It was I who killed the merchant and hid the knife among your things. I meant to kill you too, but I heard a noise outside, so I hid the knife in your bag and escaped out of the window.”

Aksionov was silent, and did not know what to say. Makar Semyonich slid off the bed-shelf and knelt upon the ground. “Ivan Dmitrich,” said he, “forgive me! For the love of God, forgive me! I will confess that it was I who killed the merchant, and you will be released and can go to your home.”

“It is easy for you to talk,” said Aksionov, “but I have suffered for you these twenty-six years. Where could I go to now?… My wife is dead, and my children have forgotten me. I have nowhere to go…”

Makar Semyonich did not rise, but beat his head on the floor. “Ivan Dmitrich, forgive me!” he cried. “When they flogged me with the knot it was not so hard to bear as it is to see you now … yet you had pity on me, and did not tell. For Christ’s sake forgive me, wretch that I am!” And he began to sob.

When Aksionov heard him sobbing he, too, began to weep. “God will forgive you!” said he. “Maybe I am a hundred times worse than you.” And at these words his heart grew light, and the longing for home left him. He no longer had any desire to leave the prison, but only hoped for his last hour to come.

In spite of what Aksionov had said, Makar Semyonich confessed, his guilt. But when the order for his release came, Aksionov was already dead.

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) short stories

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Tolstoy, Leo

Ourselves Alone*

One morning, when dreaming in deep meditation,

I met a sweet colleen a-making her moan.

With sighing and sobbing she cried and lamented;

“Oh, where is my lost one, and where has he flown?

“My house it is small, and my field is but little,

Yet round flew my wheel as I sat in the sun,

He crossed the deep sea and went forth for my battle:

Oh, has he proved faithless—the fight is not won?”

And then I said: “Kathleen, ah! do you remember

When you were a queen, and your castles were strong,

You cried for the love of a cold-hearted stranger,

And in your fair island you planted the wrong?

“And oh,” I cried, “Kathleen, I once heard you weeping

And sighing and sobbing and making your moan.

You sang of a lost one, a dear one, a false one—

‘Oh, gone is my blackbird, and where has he flown?’

“Ah! many came forth to the sound of your crying,

And fought down the years for the freedom you pined.

How many lie still, in their cold exile sleeping,

Who sought in far lands your lost blackbird to find?

“And many are caught in the net of the stranger,

And all but forgotten the sound of your name,

For other loves call them to help and to save them:

They fell to dishonour—we hold them in shame.

“Oh, why drive me forth from your hearth into exile

And into far dangers? Your house is my own.

Faithful I serve, as I ever did serve you,

Standing together, ourselves—and alone.”

*Sinn Fein Amhain

Dora Maria Sigerson Shorter

(1866 – 1918)

Ourselves Alone

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Sigerson Shorter, Dora Maria, WAR & PEACE

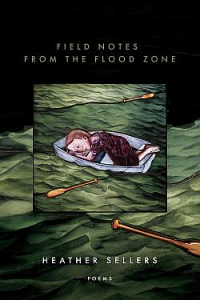

From the frontlines of climate catastrophe, a poet watches the sea approach her doorstep.

Born and raised in Florida, Heather Sellers grew up in an extraordinarily difficult home. The natural world provided a life-giving respite from domestic violence. She found, in the tropical flora and fauna, great beauty and meaningful connection. She made her way by trying to learn the name of every flower, every insect, every fish and shell and tree she encountered.

Born and raised in Florida, Heather Sellers grew up in an extraordinarily difficult home. The natural world provided a life-giving respite from domestic violence. She found, in the tropical flora and fauna, great beauty and meaningful connection. She made her way by trying to learn the name of every flower, every insect, every fish and shell and tree she encountered.

In this collection of poems, Sellers laments its loss, while observing, over the course of a year, daily life of the people and other animals around her, on her street, and in her low-lying coastal town, where new high rises soar into the sky as the storm clouds gather with increasing intensity and the future of the community—and seemingly life as we know it—becomes more and more uncertain.

Sprung from her daily observation journals, haunted by ghosts from the past, Field Notes from the Flood Zone is a double love letter: to a beautiful and fragile landscape, and to the vulnerable young girl who grew up in that world. It is an elegy for the two great shaping forces in a life, heartbreaking family struggle and a collective lost treasure, our stunning, singular, desecrated Florida, and all its remnant beauty.

Heather Sellers is the author of four poetry collections: Field Notes from the Flood Zone (BOA, 2022); The Present State of the Garden (Lynx House Press, 2021); The Boys I Borrow (New Issues Press, 2007), which was a finalist for the James Laughlin Award; and Drinking Girls and Their Dresses (Ahsahta Press, 2002). She is also the author of the memoir You Don’t Look Like Anyone I Know (Riverhead, 2011), which was an O, the Oprah Magazine Book of the Month Club Choice and an Editor’s Choice at the New York Times, and the craft book The Practice of Creative Writing (Macmillan St. Martins Bedford, 2021), now in its fourth edition.

Her writing has been featured in numerous publications and anthologies, including Best American Essays, Creative Nonfiction, Good Housekeeping, The New York Times, O, the Oprah Magazine, The Pushcart Prize Anthology, Reader’s Digest, The Sun, and Tin House. She has been awarded a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts and a residency at The MacDowell Colony. She teaches poetry and nonfiction in the MFA program at the University of South Florida. A native Floridian, she divides her time between St. Petersburg, Florida, and Manhattan.

Field Notes from the Flood Zone

By Heather Sellers

Publisher: BOA Editions Ltd. (April 26, 2022)

Language: English

Paperback: 80 pages

ISBN-10: 1950774570

ISBN-13 : 978-1950774579

$ 17.00

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, Archive S-T, Archive S-T

Season of Dares leans into fragments of the scriptures, narratives and mythologies of a Korean adoptee’s childhood in the rural American West.

Fearlessly, it revisits and explores the physical and spiritual landscapes of those communities and the tensions between the impulses that shaped them–violence and tenderness, stoicism and sentimentalism, self-reliance and belief in divine providence.

Fearlessly, it revisits and explores the physical and spiritual landscapes of those communities and the tensions between the impulses that shaped them–violence and tenderness, stoicism and sentimentalism, self-reliance and belief in divine providence.

Born in South Korea and raised in Montana and Colorado, Leah Silvieus now travels between Florida and New York as a yacht chief stewardess.

Silvieus is the author of a chapbook, Anemochory (Hyacinth Girl Press 2016), and a books editor for Hyphen magazine. She is also a Kundiman fellow and the recipient of awards and fellowships from The Academy of American Poets, Fulbright, and the Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation.

Leah Silvieus holds an MFA from the University of Miami.

Season of Dares

by Leah Silvieus (Author)

Publisher: Bull City Press

2018

Language: English

Paperback: 28 pages

ISBN-10: 149517879X

ISBN-13: 978-1495178795

$23.20

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, Archive S-T, Archive S-T

Poetry. An Insomniac’s Slumber Party with Marilyn Monroe is a middle-of-the-night poetic conversation with Marilyn Monroe that explores obsessions, addictions, abuse, objectification, marriage, work, children, childlessness and death.

Pressing on the themes of her acclaimed debut, Give a Girl Chaos, Seaborn illuminates the biographical and emotional journey of Marilyn as intimacies whispered between two women.

Pressing on the themes of her acclaimed debut, Give a Girl Chaos, Seaborn illuminates the biographical and emotional journey of Marilyn as intimacies whispered between two women.

These are women who have lived “on the glittering edge” and know that when a third husband “draws a blank page from his typewriter,” it means she needs to go to work in a world dominated by men.

In An Insomniac’s Slumber Party with Marilyn Monroe, Marilyn is a resilient, intelligent feminist who understands how to accumulate and wield power in the 1950’s. She is also vulnerable, exploited, and broken in so many ways.

We see the speaker discover Marilyn until “then she is everywhere,” a haunting presence that becomes both muse and reflection. Seaborn invites us into the poetic soul of the world’s most famous woman with poems that celebrate and mourn. An Insomniac’s Slumber Party with Marilyn Monroe is a sequined meditation on what keeps us up at night and what fills our dreams.

Heidi Seaborn wrote poetry as teenager then pursued a career as a business executive. She moved 27 times, raised three children, divorced and remarried and then after a 40-year hiatus, returned to poetry in 2016. Since then she’s authored two full-length collections of poetry and three chapbooks of poetry, won or been shortlisted for over two dozen awards and been published widely. She is Executive Editor of THE ADROIT JOURNAL and holds an MFA in Poetry from NYU and a BA from Stanford University. She lives in Seattle.

An Insomniac’s Slumber Party with Marilyn Monroe

by Heidi Seaborn (Author)

Paperback

June 10, 2021

Pages: 84

Publisher: PANK Books (June 10, 2021)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 194858719X

ISBN-13: 978-1948587198

$18.00

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Biography Archives, #Modern Poetry Archive, Archive S-T, Archive S-T

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature