Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

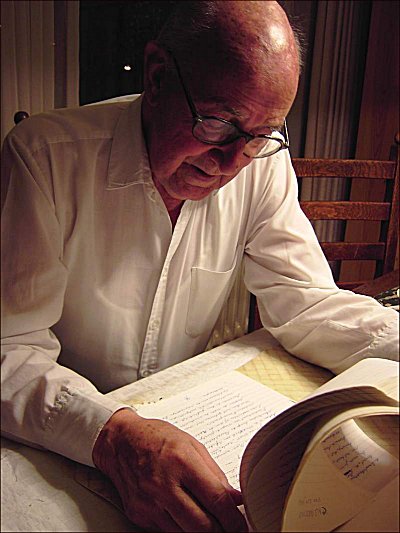

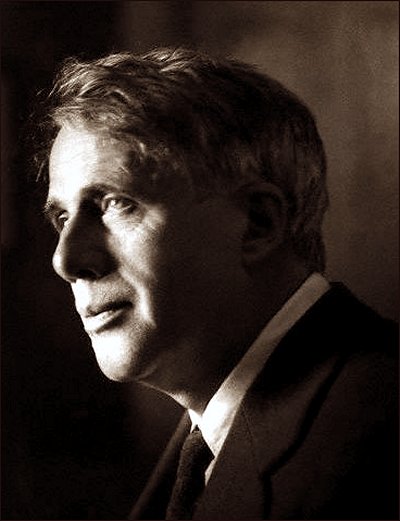

In Memoriam Anton (Toon) Eijkens

(1920-2012)

Anton Eijkens schreef de Tilburgse historie in 1000 dichtregels

TILBURG – In het verzorgingshuis Koningsvoorde is afgelopen zaterdagochtend Antonius Maria Eijkens overleden. Toon Eijkens heeft diverse boeken op zijn naam staan en schreef ook de Tilburgse rijmkroniek die burgemeester Jan van de Mortel in 1946 bij zijn afscheid aangeboden kreeg van de Tilburgse bevolking. Het beschrijft de geschiedenis van Tilburg in duizend dichtregels.

Eijkens werd in 1920 te Tilburg geboren en volgde het gymnasium op het St. Odulphuslyceum waar hij zich al vroeg ontpopte als een jongeman met talent voor taal en muziek én als dichter. Zijn vader vond een baan voor hem bij Bureau Van Spaendonck. Het stond zijn literaire ambities niet in de weg. Onder de naam Anton Eijkens schreef hij artikelen en verhalen in de bladen Brabantia Nostra en Edele Brabant, waar hij ook in de redactie zat.

In 1946 beleefde Anton Eijkens zijn productiefste jaar. Hij publiceerde toen onder meer de verhalenbundel Rond de toren, de bloemlezing De Sprookjeshoorn en Een handvol verzen. Bovendien schreef hij samen met Jan Naaijkens het scenario en de teksten voor het massale openluchtspel Kruis en Ploeg dat in de zomer van 1946 bij gelegenheid van het 50-jarig bestaan van de Noord-Brabantse Christelijke Boerenbond (NBC) opgevoerd werd in het Willem II-stadion. Kort erna werd aan burgemeester Van de Mortel het gedenkboek Rijmkroniek van Tilburg, het hart van Brabant aangeboden, een uniek in kalfsleer gebonden boek waarvan de door Eijkens geschreven tekst geheel gekalligrafeerd was door zijn zwager Kees Mandos.

Ook in de daarop volgende jaren bleef Eijkens actief als schrijver, zij het vooral van gelegenheidsliederen voor zijn collega’s en van gedenkboeken voor het bedrijfsleven en voor Bureau Van Spaendonck zelf. Daar nam hij in 1984 afscheid als secretaris van diverse werkgeversorganisaties en directeur van de Sector Secretariaten.

Toon Eijkens was getrouwd met Thea Mandos met wie hij zeven kinderen kreeg. In 1982 werd hij geridderd in de Orde van Oranje Nassau.

Anton Eijkens

(1920-2012)

Voor de Beminde

Mijn liederen zijn gering als schaamle kinderen,

die voor een aalmoes komen zingen aan je raam,

als ‘t daglicht in de straat begint te minderen

en aan de avondlucht de eerste sterren staan.

Wie zal mij in mijn schamelheid verhinderen

mijn leed en vreugd te komen zingen aan je raam?

Ik weet: jij kunt het lied van schaamle kinderen

niet zonder mildheid langs je venster laten gaan.

Ontmoeting

Ik had maar de kortste weg genomen,

een weg vol distels en woekerkruid,

want de avond viel dichter in de bomen

en de wind blies langzaam de sterren uit.

Maar aan de rand van een bloeiende tuin,

geurend van appels, pruimen en peren,

blies een bultenaar op zijn kranke bazuin;

“Kunt gij het geluk uw rug toekeren?”

Hoe vreemd: teruggaand heb ik genomen

de langste weg, langs de hoogste bomen.

Anton Eijkens: Twee gedichten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Eijkens, Anton, In Memoriam

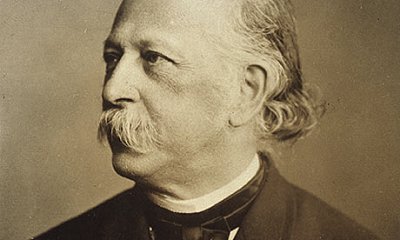

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Im Garten

Die hohen Himbeerwände

Trennten dich und mich,

Doch im Laubwerk unsre Hände

Fanden von selber sich.

Die Hecke konnt’ es nicht wehren,

Wie hoch sie immer stund:

Ich reichte dir die Beeren,

Und du reichtest mir deinen Mund.

Ach, schrittest du durch den Garten

Noch einmal im raschen Gang,

Wie gerne wollt’ ich warten,

Warten stundenlang.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

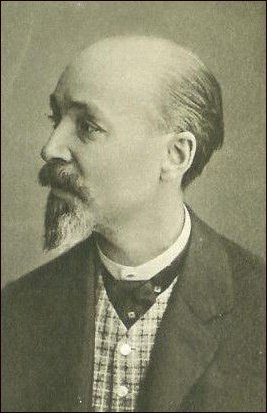

Max Elskamp

(1862-1931)

La femme

Mais maintenant vient une femme,

Et lors voici qu’on va aimer,

Mais maintenant vient une femme

Et lors voici qu’on va pleurer,

Et puis qu’on va tout lui donner

De sa maison et de son âme,

Et puis qu’on va tout lui donner

Et lors après qu’on va pleurer

Car à présent vient une femme,

Avec ses lèvres pour aimer,

Car à présent vient une femme

Avec sa chair tout en beauté,

Et des robes pour la montrer

Sur des balcons, sur des terrasses,

Et des robes pour la montrer

A ceux qui vont, à ceux qui passent,

Car maintenant vient une femme

Suivant sa vie pour des baisers,

Car maintenant vient une femme,

Pour s’y complaire et s’en aller.

Max Elskamp poetry

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Archive E-F, Elskamp, Max

max liebermann

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

O trübe diese Tage nicht

O trübe diese Tage nicht,

Sie sind der letzte Sonnenschein,

Wie lange, und es lischt das Licht,

Und unser Winter bricht herein.

Dies ist die Zeit, wo jeder Tag

Viel Tage gilt in seinem Wert,

Weil man’s nicht mehr erhoffen mag,

Daß so die Stunde wiederkehrt.

Die Flut des Lebens ist dahin,

Es ebbt in seinem Stolz und Reiz,

Und sieh, es schleicht in unsern Sinn

Ein banger, nie gekannter Geiz;

Ein süßer Geiz, der Stunden zählt

Und jede prüft auf ihren Glanz,

O sorge, daß uns keine fehlt,

Und gönn uns jede Stunde ganz

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Der echte Dichter

(Wie man sich früher ihn dachte)

Ein Dichter, ein echter, der Lyrik betreibt,

Mit einer Köchin ist er beweibt,

Seine Kinder sind schmuddlig und unerzogen,

Kommt der Mietszettelmann, so wird tüchtig gelogen,

Gelogen, gemogelt wird überhaupt viel,

»Fabulieren« ist ja Zweck und Ziel.

Und ist er gekämmt und gewaschen zuzeiten,

So schafft das nur Verlegenheiten,

Und ist er gar ohne Wechsel und Schulden

Und empfängt er pro Zeile ‘nen halben Gulden

Oder pendeln ihm Orden am Frack hin und her,

So ist er gar kein Dichter mehr,

Eines echten Dichters eigenste Welt

Ist der Himmel und – ein Zigeunerzelt.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Mein Herze, glaubt’s, ist nicht erkaltet

Mein Herze, glaubt’s, ist nicht erkaltet,

Es glüht in ihm so heiß wie je,

Und was ihr drin für Winter haltet,

Ist Schein nur, ist gemalter Schnee.

Doch, was in alter Lieb’ ich fühle,

Verschließ ich jetzt in tiefstem Sinn,

Und trag’s nicht fürder ins Gewühle

Der ewig kalten Menschen hin.

Ich bin wie Wein, der ausgegoren:

Er schäumt nicht länger hin und her,

Doch was nach außen er verloren,

Hat er an innrem Feuer mehr.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

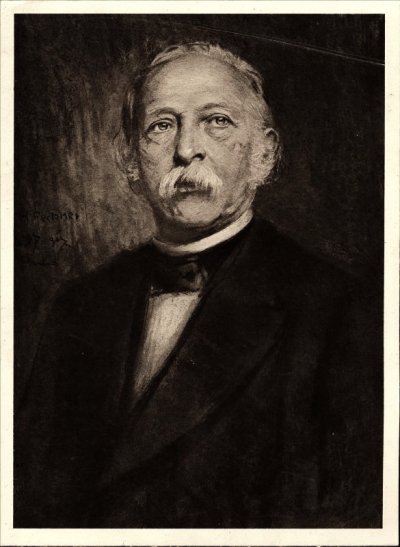

theodor fontane by max liebermann

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Memento

Geliebte, willst du doppelt leben,

So sei des Todes gern gedenk

Und nimm, was dir die Götter geben,

Tagtäglich hin wie ein Geschenk.

Mach dich vertraut mit dem Gedanken,

Daß doch das Letzte kommen muß,

Und statt in Trübsinn hinzukranken,

Wird dir das Dasein zum Genuß.

Du magst nicht länger mehr vergeuden

Die Spanne Zeit in eitlem Haß,

Du freust dich reiner deiner Freuden

Und sorgst nicht mehr um dies und das.

Du setzest an die rechte Stelle

Das Hohe, Göttliche der Zeit,

Und jede Stunde wird dir Quelle

Gesteigert neuer Dankbarkeit.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Das Fischermädchen

Steht auf sand’gem Dünenrücken

Eine Fischerhütt’ am Strand;

Abendrot und Netze schmücken

Wunderlich die Giebelwand.

Drinnen spinnt und schnurrt das Rädchen,

Blaß der Mond ins Fenster scheint,

Still am Herd das Fischermädchen

Denkt des letzten Sturms und – weint.

Und es klagen ihre Tränen:

»Weit der Himmel, tief die See,

Doch noch weiter geht mein Sehnen,

Und noch tiefer ist mein Weh.«

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Frühling

Nun ist er endlich kommen doch

In grünem Knospenschuh;

“Er kam, er kam ja immer noch”,

Die Bäume nicken sich’s zu.

Sie konnten ihn all erwarten kaum,

Nun treiben sie Schuss auf Schuss;

Im Garten der alte Apfelbaum,

Er sträubt sich, aber er muss.

Wohl zögert auch das alte Herz

Und atmet noch nicht frei,

Es bangt und sorgt: “Es ist erst März

Und März ist noch nicht Mai.”

O schüttle ab den schweren Traum

Und die lange Winterruh:

Es wagt es der alte Apfelbaum,

Herze, wag’s auch du.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

Robert Frost

(1874-1963)

The Death of the Hired Man

Mary sat musing on the lamp-flame at the table

Waiting for Warren. When she heard his step,

She ran on tip-toe down the darkened passage

To meet him in the doorway with the news

And put him on his guard. “Silas is back.”

She pushed him outward with her through the door

And shut it after her. “Be kind,” she said.

She took the market things from Warren’s arms

And set them on the porch, then drew him down

To sit beside her on the wooden steps.

“When was I ever anything but kind to him?

But I’ll not have the fellow back,” he said.

“I told him so last haying, didn’t I?

‘If he left then,’ I said, ‘that ended it.’

What good is he? Who else will harbour him

At his age for the little he can do?

What help he is there’s no depending on.

Off he goes always when I need him most.

‘He thinks he ought to earn a little pay,

Enough at least to buy tobacco with,

So he won’t have to beg and be beholden.’

‘All right,’ I say, ‘I can’t afford to pay

Any fixed wages, though I wish I could.’

‘Someone else can.’ ‘Then someone else will have to.’

I shouldn’t mind his bettering himself

If that was what it was. You can be certain,

When he begins like that, there’s someone at him

Trying to coax him off with pocket-money,–

In haying time, when any help is scarce.

In winter he comes back to us. I’m done.”

“Sh! not so loud: he’ll hear you,” Mary said.

“I want him to: he’ll have to soon or late.”

“He’s worn out. He’s asleep beside the stove.

When I came up from Rowe’s I found him here,

Huddled against the barn-door fast asleep,

A miserable sight, and frightening, too–

You needn’t smile–I didn’t recognise him–

I wasn’t looking for him–and he’s changed.

Wait till you see.”

“Where did you say he’d been?”

“He didn’t say. I dragged him to the house,

And gave him tea and tried to make him smoke.

I tried to make him talk about his travels.

Nothing would do: he just kept nodding off.”

“What did he say? Did he say anything?”

“But little.”

“Anything? Mary, confess

He said he’d come to ditch the meadow for me.”

“Warren!”

“But did he? I just want to know.”

“Of course he did. What would you have him say?

Surely you wouldn’t grudge the poor old man

Some humble way to save his self-respect.

He added, if you really care to know,

He meant to clear the upper pasture, too.

That sounds like something you have heard before?

Warren, I wish you could have heard the way

He jumbled everything. I stopped to look

Two or three times–he made me feel so queer–

To see if he was talking in his sleep.

He ran on Harold Wilson–you remember–

The boy you had in haying four years since.

He’s finished school, and teaching in his college.

Silas declares you’ll have to get him back.

He says they two will make a team for work:

Between them they will lay this farm as smooth!

The way he mixed that in with other things.

He thinks young Wilson a likely lad, though daft

On education–you know how they fought

All through July under the blazing sun,

Silas up on the cart to build the load,

Harold along beside to pitch it on.”

“Yes, I took care to keep well out of earshot.”

“Well, those days trouble Silas like a dream.

You wouldn’t think they would. How some things linger!

Harold’s young college boy’s assurance piqued him.

After so many years he still keeps finding

Good arguments he sees he might have used.

I sympathise. I know just how it feels

To think of the right thing to say too late.

Harold’s associated in his mind with Latin.

He asked me what I thought of Harold’s saying

He studied Latin like the violin

Because he liked it–that an argument!

He said he couldn’t make the boy believe

He could find water with a hazel prong–

Which showed how much good school had ever done him.

He wanted to go over that. But most of all

He thinks if he could have another chance

To teach him how to build a load of hay—-“

“I know, that’s Silas’ one accomplishment.

He bundles every forkful in its place,

And tags and numbers it for future reference,

So he can find and easily dislodge it

In the unloading. Silas does that well.

He takes it out in bunches like big birds’ nests.

You never see him standing on the hay

He’s trying to lift, straining to lift himself.”

“He thinks if he could teach him that, he’d be

Some good perhaps to someone in the world.

He hates to see a boy the fool of books.

Poor Silas, so concerned for other folk,

And nothing to look backward to with pride,

And nothing to look forward to with hope,

So now and never any different.”

Part of a moon was falling down the west,

Dragging the whole sky with it to the hills.

Its light poured softly in her lap. She saw

And spread her apron to it. She put out her hand

Among the harp-like morning-glory strings,

Taut with the dew from garden bed to eaves,

As if she played unheard the tenderness

That wrought on him beside her in the night.

“Warren,” she said, “he has come home to die:

You needn’t be afraid he’ll leave you this time.”

“Home,” he mocked gently.

“Yes, what else but home?

It all depends on what you mean by home.

Of course he’s nothing to us, any more

Than was the hound that came a stranger to us

Out of the woods, worn out upon the trail.”

“Home is the place where, when you have to go there,

They have to take you in.”

“I should have called it

Something you somehow haven’t to deserve.”

Warren leaned out and took a step or two,

Picked up a little stick, and brought it back

And broke it in his hand and tossed it by.

“Silas has better claim on us you think

Than on his brother? Thirteen little miles

As the road winds would bring him to his door.

Silas has walked that far no doubt to-day.

Why didn’t he go there? His brother’s rich,

A somebody–director in the bank.”

“He never told us that.”

“We know it though.”

“I think his brother ought to help, of course.

I’ll see to that if there is need. He ought of right

To take him in, and might be willing to–

He may be better than appearances.

But have some pity on Silas. Do you think

If he’d had any pride in claiming kin

Or anything he looked for from his brother,

He’d keep so still about him all this time?”

“I wonder what’s between them.”

“I can tell you.

Silas is what he is–we wouldn’t mind him–

But just the kind that kinsfolk can’t abide.

He never did a thing so very bad.

He don’t know why he isn’t quite as good

As anyone. He won’t be made ashamed

To please his brother, worthless though he is.”

“I can’t think Si ever hurt anyone.”

“No, but he hurt my heart the way he lay

And rolled his old head on that sharp-edged chair-back.

He wouldn’t let me put him on the lounge.

You must go in and see what you can do.

I made the bed up for him there to-night.

You’ll be surprised at him–how much he’s broken.

His working days are done; I’m sure of it.”

“I’d not be in a hurry to say that.”

“I haven’t been. Go, look, see for yourself.

But, Warren, please remember how it is:

He’s come to help you ditch the meadow.

He has a plan. You mustn’t laugh at him.

He may not speak of it, and then he may.

I’ll sit and see if that small sailing cloud

Will hit or miss the moon.”

It hit the moon.

Then there were three there, making a dim row,

The moon, the little silver cloud, and she.

Warren returned–too soon, it seemed to her,

Slipped to her side, caught up her hand and waited.

“Warren,” she questioned.

“Dead,” was all he answered.

Robert Frost poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F

Joseph von Eichendorff

(1788—1857)

Waldgespräch

Es ist schon spät, es wird schon kalt,

Was reitst du einsam durch den Wald?

Der Wald ist lang, du bist allein,

Du schöne Braut! Ich führ dich heim!

»Groß ist der Männer Trug und List,

Vor Schmerz mein Herz gebrochen ist,

Wohl irrt das Waldhorn her und hin,

O flieh! Du weißt nicht, wer ich bin.«

»Du kennst mich wohl – von hohem Stein

Schaut still mein Schloß tief in den Rhein.

Es ist schon spät, es wird schon kalt,

Kommst nimmermehr aus diesem Wald!«

Hans Hermans photos – Natuurdagboek 9-11

Gedicht Joseph von Eichendorff

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Hans Hermans Photos, MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY - department of ravens & crows, birds of prey, riding a zebra, spring, summer, autumn, winter

Anton Eijkens

Vademecum van een liefhebber (13)

Epiloog

Ik zei vannacht en hield de beker hooggeheven:

“De volle kroes zij immer ‘t teken van mijn leven.”

Vanmorgen werd ik wakker naast mijn trouwe kroes,

waarvan niets dan ‘t armzalig oor was heel gebleven.

*

Er komt een dag, dat brood en wijn

onaangeroerd op tafel staan;

wij zullen niet meer samen zijn

en moeten vreemde wegen gaan.

Er komt een dag, dat wij niet meer

in liefde zacht geborgen zijn.

Hoe proef ik bitter het weleer

hier in dit brood, in deze wijn.

*

O mens die zonder rust of duur

naar ‘s werelds bonte vreugden haakt,

gedenk, zij vroeg of laat het uur,

dat gij van aarde zijt gemaakt

en weer tot aarde keren zult:

en broze kruik, tot aan de rand

nu nog met wijn en geur gevuld

maar eenmaal scherven in het zand.

Anton Eijkens: Vademecum van een liefhebber (13)

Epiloog

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Eijkens, Anton

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature