Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

45ste Poetry International 2014

“Meisjes zijn het allermooist op aard”

door Carina van der Walt

2014 – 06 – 17

Woensdag 11 juni was een stralend zonnige dag in Rotterdam. Een dag voor mooie meisjes à la Raymond van het Groenewoud de Belgische zanger. Het was de eerste volle dag bij Poetry International na de Vlaggenparade en Festivalopening de vorige avond. Het dagprogramma werd uitgedeeld met een citaat van Jules Deelder als kop: Hoe langer je leeft / hoe korter het duurt. Jules is zeker het gezicht van de Rotterdamse dichterswereld als nachtburgemeester en na tien deelnames aan Poetry International tussen 1970 en 2000. Hij was ook op deze avond de gast van een programma met dezelfde titel. Daarom was het ook gepast dat de gasten bij binnenkomst direct met deze dichtregel uit zijn hand verwelkomd werden. De meerderheid van de activiteiten was gelokaliseerd in de Rotterdamse Schouwburg. In de stad waren fiets- en kunstroutes die alles te maken hadden met poëzie in de wijdste betekenis. Maar wie op een dag bezoek komt, moest keuzes maken.

In het Douw Egberts Café (DE Café) naast de tramhalte en 150 meter van de gloednieuw gerenoveerde stationshal, gingen we op het eerste programma af. Dit programma is een initiatief van Dean Bowen, die ook als gastheer optrad. De eerste twee gasten om 14:00 waren Véronique Pitollo uit Frankrijk en Antoine de Kom, VSB Poëzieprijswinnaar. We krijgen elk een hand out met een vertaling van Pitollos werk door Rokus Hofstede. Heel handig. Pitollo vertelde tijdens de introductie dat haar voorlezing niet het palet geeft van haar stijl, maar speciaal voor Poetry International geschreven is. Zij las voor uit HET MEISJE EN UTOPIEëN:

p.1

Kinderloze koningen en koninginnen krijgen aan het eind meestal een meisje.

Een meisje!

De kreet van teleurstelling weerklinkt in het hele koninkrijk. Ze zijn teleurgesteld.

Dat kind moet een belofte zijn van geschenken, voorspellingen rond de wieg, een prins en alles wat daaruit volgt. Men schat ziektes in, somt successen op.

Een levensweg, wat is dat? Grote verwachtingen in de lijnen van de hand, ja… Maar verder? Wie de slechte kaart trekt als de rollen van ‘vader, moeder, kind’ worden vergeven, zal het zich heugen.

p.2

Is ze eenmaal tot wasdom gekomen, dan stelt men zich het meisje voor aan de arm van een cavalier. Maar cavaliers gaan voorbij en meisjes blijven… het leven vliegt heen aan het stuur van een cabriolet.

(Geboren worden als meisje is een handicap die erop neerkomt dat je twee keer zo levend bent als een jongen).

p.3

Als zelfbevrijding de droom van de mensheid is, dan maakt het meisje er deel van uit.

Ze maakt deel uit van dat grote voorwaartse streven: die trage overtocht.

Voor knappe meisjes met een smalle taille is het makkelijker: volkomen onafhankelijke als ze zijn, worden ze bevoorrecht. Toch is de grond wankel voor een vurig jong ding, toch zijn de muren scheef.

Wat het meisje verklaart, zijn de gemiste treden.

De andere voegen zich bij de onbehoorlijke massa, de zusjes voor de spiegels.

Het is verbijsterend. Voor haar weerschijn grimas het lelijke wicht. Om dat ene mooie meisje te zijn tussen alle andere, moet je bedrog plegen met je spiegelbeeld.

In een prozagedicht van veertien pagina’s vertelde Pitollo van alle ongemakken, verwachtingen en teleurstellingen van een koningsdochter. Uit het kleine publiek in DE Café merkte iemand achteraf overeenkomsten en verschillen op in het meisjesperspectief van de poëzie van Kreek Daey Ouwens. Er worden contactgegevens uitgeruild.

In een prozagedicht van veertien pagina’s vertelde Pitollo van alle ongemakken, verwachtingen en teleurstellingen van een koningsdochter. Uit het kleine publiek in DE Café merkte iemand achteraf overeenkomsten en verschillen op in het meisjesperspectief van de poëzie van Kreek Daey Ouwens. Er worden contactgegevens uitgeruild.

De tweede gast was Antoine de Kom. Hij las onder andere zijn gedichten made in honduras en hafez bashar maher voor uit de bekroonde bundel Ritmisch zonder string (2014). Op mijn vraag hoe hij zijn bezoek aan Zuid-Afrika ervoer, antwoordde hij met een lezing uit sea point:

ah tamanrasset zuidwaarts oh dood

geheel absurd ubuntu door de ander levend uwe dood

heeft hier ter hoogte van tamanrassat zijn grote voeten in het zand gelobd

en korstig ook zie ik een heel grote wrat. verder kan ik melden

dat dood luid snurkt. hij kan het niet helpen. tot diep in de nacht

zat hij te mailen en nu plagen hem talloze overlevenden

die hem slapeloos in hun sahara vrezen

klein zusje van dood is een woestijn die soms en langzaamaan sahel

wat groener wordt zodat je voeten zo te zien vanuit de hoogte hier of daar

wat nat wanneer ze aan de oever van een meer of meer rivier.

het mist. en je verwacht hem ieder ogenblik. waaraan herken

je hem? wat is zijn teken of besluit zodat hij aan je komt?

zijn zusje zwijgt. je weet nog wel: dood heeft een smoel

en wie weet is die kaaps in kaapstad

nu wordt dood toerist van alle kleuren thuis

erg druk was het tussen de vissen en heel warm toen de piloot opeens

zei: dat schip zinkt! het zinkt en daalde hij verder naar de haven

verderop. we hebben gevlogen rond de tafelberg de dichtheid van de townships

vastgesteld. na de vlekkeloze landing zagen we de waarheid onder ogen.

geen commissie die het na kan doen: dit is een verdrietig land

waar medemensen als verschrikte vogels uiteenstuiven wanneer

dood als mijn wit van deze bladzij hen te na komt

Het personage dood van dit gedicht van Antoine de Kom is “alive and well” aan de zuidpunt van Afrika. Wat kan ik erop zeggen? Behalve dat ook hierin een meisje voorkomt: het zusje van dood die zwijgt.

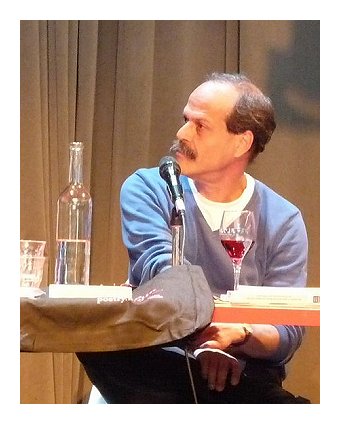

Ik ben eigenlijk gegaan voor mijn landgenoot Charl-Pierre Naudé, maar in de schouwburg van Rotterdam was hij nog nergens te zien. Tijdens de Poëziecafe met Daniël Dee (huidige stadsdichter van Rotterdam, maar geboren in Zuid-Afrika) kijk ik even bij De Huisdrukker rond. Zou Naudé ondertussen (na onze laatste ontmoeting in Maastricht) zo een grote snor hebben gekweekt? Ik stap op een man af met dezelfde postuur als Naudé en spreek hem aan. Nee, hij is de Turkse dichter Roni Margulies uit Istanbul. Hij is in NU aan de beurt bij Dee. Ik moet hem excuseren.

Zo leerde ik tijdens zijn zeer dynamische optrede over het programma A View with a Room. De initiatiefnemer is Eric Dullaert. Hij werkte samen met Poetry International. Margulies is nu zes weken “writer in residence” in Rotterdam Zuid. Hij is gefascineerd door thema’s als identiteit, migratie, grenzen, taal en onderdrukking. Hij heeft in deze tijd zeventien gedichten geschreven over het gebied rond de Maas. Voor Poetry International heeft Margulies een prachtig linnen doosje met tien van zijn zeventien gedichten samengesteld. Ik herkende de typische blik en vragen van iemand in de marge van een nieuwe samenleving. Ook Margulies heeft het over meisjes, kassa meisjes, in zijn gedicht Burcu, Yonca en Defne vertaald door Sytske Sötemann.

Burcu, Yonca en Defne

Om de dag loop ik de Dortselaan af

en koop bij Albert Hein brood en sigaretten,

en oude Franse kaas, diverse dranken,

en allerlei soorten varkensproducten.

De laatste keer zat Burcu achter de kassa,

daarvoor was het Yonca, een andere keer Defne.

Op hun kraag hebben ze allemaal een naamkaartje.

Ik zeg alleen “Dank je wel.”

Gisteren keek Burca naar de pakjes ham,

ze aarzelde, keek naar mij, twijfelde,

ten slotte was ze ervan overtuigd dat ik Turks was.

“Meneer,” zei ze, “wat u daar heeft gekocht is varken.”

“Dat weet ik,” zei ik, “Wij hebben dat niet,

daarom ben ik het gekocht. Soms heb ik er zin in.”

“Wie zijn wij?” dacht ik later,

toen ik op m’n gemak naar huis liep.

Zou Burca dat ook gedacht hebben,

toen ze me enigszins bezorgd nakeek:

“Hij is duidelijk geen Nederlander, maar

wat dan wel, is een beetje moeilijk te zeggen.”

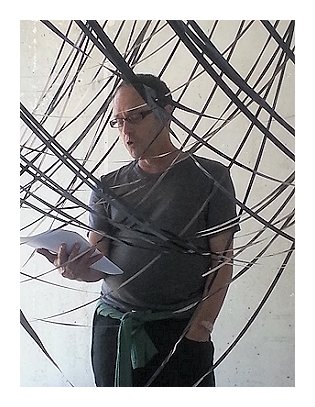

Uiteindelijk was het de tijd voor de avondprogramma’s. In de Kleine Zaal kwamen vroeg ’s avonds Adam Dickinson (Canada), Alfred Schaffer (Nederland), Charl-Pierre Naudé (Zuid-Afrika) en Habib Tengour (Algerije / Frankrijk) bijeen om elk ongeveer vijftien minuten uit hun werk voor te lezen. Al snel kwam ik zeer onder de indruk van Dickinsons gedichten uit zijn bundel The Polymers. Hij combineerde literatuur en wetenschap. In zijn gedichten onderzoekt hij de structuur en het gedrag van “polymers” of grote moleculen met identieke vormen in verschillende combinaties.

Het poëziepubliek genoot van de virtuositeit van Naudé als dichter. Ze horen half bekende en half vreemde woorden in zijn voordracht; bekende verwijzingen als “Stonehenge” en onbekende verwijzingen als “samekoms-met-handradio’s”. Ik zie voor me een andere Naudé dan bijna twintig jaar geleden. Hij debuteerde toen met Die nomadiese oomblik (1995). Het was een nogal intellectualistische bundel waarvoor hij de Ingrid Jonker Prijs ontving. Hoewel de sociale en politieke toestanden in Zuid-Afrika vaak op een persoonlijk niveau een plaats in zijn gedichten krijgen, is Naudé geen activist. Hij sloot ons dagje Rotterdam af met:

Nawoord

I

Miskien, toentertyd,

was daar tafels gedek

by Stonehedge:

kliptafels

met godewette daarop

’n banket

van smeulende offerandes

wat in geplette bordjes

rondgedra is

in ’n kring van die feromone

– soos popdeuntjies

wat rook uit ’n samekoms-met-handradio’s

van die maagde.

Die windjie slinger

en neurie deur die gras,

soos borduurwerk

met some langs,

en skielik moker

die weerlig alles plat

tot op ’n verpulpte neusbrug,

tot ín die tydlose skerwe

van die erdewerk,

waar argeoloë

duisend jaar later ’n prentjie bymekaar skraap

van ene Pete Townshend,

van The Who.

II

Jy sou skaars dink dié formule

het Afrika toe gehink

oor die tydelike vlaksee –

of was die rigting andersom?

……

Dáár

sien ek die tiara,

die halfsirkel-waterval

Victoria,

wat al hoe dieper in die aarde wegsink,

en skitterend na binne kolk

sonder om iets

koninkliks en verswelgends na buite

uit te vaardig.

Zo was het genoeg voor één dag. De ingeperkte koningsdochter “als verlengstuk van de moeder” (p. 14 in de voordracht van Pitollo eerder op de dag) groeide in Naudés voordracht onbedoeld uit tot een grandioze waterval met de naam Victoria. Mijn verstand zei nog: ga luisteren naar Jules Deelder, maar mijn beker was vol. Die dichters die op deze dag uitkwamen als de lievelingen van de pers waren Naudé en Deelder, elk met een artikel in het NRC Handelsblad. In het najaar van 2014 zal Naudés Al die lieflike dade bij Uitgeverij Tafelberg verschijnen. De laatste bundel van Deelders was Ruisch (De Bezige Bij, 2011).

Foto’s: Carina van der Walt

1 – Dichteressen Kreek Daey Ouwens en Emma Crebolder aan de zij van deelnemende dichter Antoine de Kom

2 – De Franse dichteres Veronique Pitollo in gesprek met Dean Bowen in DE Café

3 – De Turkse dichter Roni Margulies vertelt van zijn ervaringen als “writer in residence” de afgelopen zes weken in Rotterdam Zuid.

4 – Charl-Pierre Naudé en zijn vertaler Robert Dorsman.

5 – De Zuid-Afrikaanse dichter Charl-Pierre Naudé op het podium.

Carina van der Walt over Poetry International 2014

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Carina van der Walt, Poetry International, TRANSLATION ARCHIVE, Walt, Carina van der

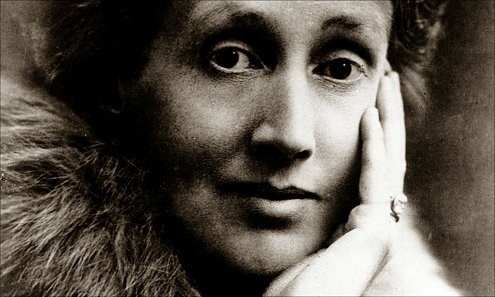

Virginia Woolf

How Should One Read a Book?

In the first place, I want to emphasize the note of interrogation at the end of my title. Even if I could answer the question for myself, the answer would apply only to me and not to you. The only advice, indeed, that one person can give another about reading is to take no advice, to follow your own instincts, to use your own reason, to come to your own conclusions. If this is agreed between us, then I feel at liberty to put forward a few ideas and suggestions because you will not allow them to fetter that independence which is the most important quality that a reader can possess. After all, what laws can be laid down about books? The battle of Waterloo was certainly fought on a certain day; but is Hamlet a better play than Lear? Nobody can say. Each must decide that question for himself. To admit authorities, however heavily furred and gowned, into our libraries and let them tell us how to read, what to read, what value to place upon what we read, is to destroy the spirit of freedom which is the breath of those sanctuaries. Everywhere else we may be bound by laws and conventions—there we have none.

But to enjoy freedom, if the platitude is pardonable, we have of course to control ourselves. We must not squander our powers, helplessly and ignorantly, squirting half the house in order to water a single rose-bush; we must train them, exactly and powerfully, here on the very spot. This, it may be, is one of the first difficulties that faces us in a library. What is “the very spot?” There may well seem to be nothing but a conglomeration and huddle of confusion. Poems and novels, histories and memories, dictionaries and blue-books; books written in all languages by men and women of all tempers, races, and ages jostle each other on the shelf. And outside the donkey brays, the women gossip at the pump, the colts gallop across the fields. Where are we to begin? How are we to bring order into this multitudinous chaos and so get the deepest and widest pleasure from what we read?

It is simple enough to say that since books have classes—fiction, biography, poetry—we should separate them and take from each what it is right that each should give us. Yet few people ask from books what books can give us. Most commonly we come to books with blurred and divided minds, asking of fiction that it shall be true, of poetry that it shall be false, of biography that it shall be flattering, of history that it shall enforce our own prejudices. If we could banish all such preconceptions when we read, that would be an admirable beginning. Do not dictate to your author; try to become him. Be his fellow-worker and accomplice. If you hang back, and reserve and criticize at first, you are preventing yourself from getting the fullest possible value from what you read. But if you open your mind as widely as possible, then signs and hints of almost imperceptible fineness, from the twist and turn of the first sentences, will bring you into the presence of a human being unlike any other. Steep yourself in this, acquaint yourself with this, and soon you will find that your author is giving you, or attempting to give you, something far more definite. The thirty-chapters of a novel—if we consider how to read a novel first—are an attempt to make something as formed and controlled as a building: but words are more impalpable than bricks; reading is a longer and more complicated process than seeing. Perhaps the quickest way to understand the elements of what a novelist is doing is not to read, but to write; to make your own experiment with the dangers and difficulties of words. Recall, then, some event that has left a distinct impression on you— how at the corner of the street, perhaps, you passed two people talking. A tree shook; an electric light danced; the tone of the talk was comic, but also tragic; a whole vision, an entire conception, seemed contained in that moment.

But when you attempt to reconstruct it in words, you will find that it breaks into a thousand conflicting impressions. Some must be subdued; others emphasized; in the process you will lose, probably, all grasp upon the emotion itself. Then turn from your blurred and littered pages to the opening pages of some great novelist—Defoe, Jane Austen, Hardy. Now you will be better able to appreciate their mastery. It is not merely that we are in the presence of a different person—Defoe, Jane Austen, or Thomas Hardy—but that we are living in a different world. Here, in Robinson Crusoe, we are trudging a plain high road; one thing happens after another; the fact and the order of the fact is enough. But if the open air and adventure mean everything to Defoe they mean nothing to Jane Austen. Hers is the drawing-room, and people talking, and by the many mirrors of their talk revealing their characters. And if, when we have accustomed ourselves to the drawing-room and its reflections, we turn to Hardy, we are once more spun round. The moors are round us and the stars are above our heads. The other side of the mind is now exposed—the dark side that comes uppermost in solitude, not the light side that shows in company. Our relations are not towards people, but towards Nature and destiny. Yet different as these worlds are, each is consistent with itself. The maker of each is careful to observe the laws of his own perspective, and however great a strain they may put upon us they will never confuse us, as lesser writers so frequently do, by introducing two different kinds of reality into the same book. Thus to go from one great novelist to another—from Jane Austen to Hardy, from Peacock to Trollope, from Scott to Meredith—is to be wrenched and uprooted; to be thrown this way and then that. To read a novel is a difficult and complex art. You must be capable not only of great fineness of perception, but of great boldness of imagination if you are going to make use of all that the novelist—the great artist—gives you.

But a glance at the heterogeneous company on the shelf will show you that writers are very seldom “great artists;” far more often a book makes no claim to be a work of art at all. These biographies and autobiographies, for example, lives of great men, of men long dead and forgotten, that stand cheek by jowl with the novels and poems, are we to refuse to read them because they are not “art?” Or shall we read them, but read them in a different way, with a different aim? Shall we read them in the first place to satisfy that curiosity which possesses us sometimes when in the evening we linger in front of a house where the lights are lit and the blinds not yet drawn, and each floor of the house shows us a different section of human life in being? Then we are consumed with curiosity about the lives of these people—the servants gossiping, the gentlemen dining, the girl dressing for a party, the old woman at the window with her knitting. Who are they, what are they, what are their names, their occupations, their thoughts, and adventures?

Biographies and memoirs answer such questions, light up innumerable such houses; they show us people going about their daily affairs, toiling, failing, succeeding, eating, hating, loving, until they die. And sometimes as we watch, the house fades and the iron railings vanish and we are out at sea; we are hunting, sailing, fighting; we are among savages and soldiers; we are taking part in great campaigns. Or if we like to stay here in England, in London, still the scene changes; the street narrows; the house becomes small, cramped, diamond-paned, and malodorous. We see a poet, Donne, driven from such a house because the walls were so thin that when the children cried their voices cut through them. We can follow him, through the paths that lie in the pages of books, to Twickenham; to Lady Bedford’s Park, a famous meeting-ground for nobles and poets; and then turn our steps to Wilton, the great house under the downs, and hear Sidney read the Arcadia to his sister; and ramble among the very marshes and see the very herons that figure in that famous romance; and then again travel north with that other Lady Pembroke, Anne Clifford, to her wild moors, or plunge into the city and control our merriment at the sight of Gabriel Harvey in his black velvet suit arguing about poetry with Spenser. Nothing is more fascinating than to grope and stumble in the alternate darkness and splendor of Elizabethan London. But there is no staying there. The Temples and the Swifts, the Harleys and the St Johns beckon us on; hour upon hour can be spent disentangling their quarrels and deciphering their characters; and when we tire of them we can stroll on, past a lady in black wearing diamonds, to Samuel Johnson and Goldsmith and Garrick; or cross the channel, if we like, and meet Voltaire and Diderot, Madame du Deffand; and so back to England and Twickenham—how certain places repeat themselves and certain names!—where Lady Bedford had her Park once and Pope lived later, to Walpole’s home at Strawberry Hill. But Walpole introduces us to such a swarm of new acquaintances, there are so many houses to visit and bells to ring that we may well hesitate for a moment, on the Miss Berrys’ doorstep, for example, when behold, up comes Thackeray; he is the friend of the woman whom Walpole loved; so that merely by going from friend to friend, from garden to garden, from house to house, we have passed from one end of English literature to another and wake to find ourselves here again in the present, if we can so differentiate this moment from all that have gone before. This, then, is one of the ways in which we can read these lives and letters; we can make them light up the many windows of the past; we can watch the famous dead in their familiar habits and fancy sometimes that we are very close and can surprise their secrets, and sometimes we may pull out a play or a poem that they have written and see whether it reads differently in the presence of the author. But this again rouses other questions. How far, we must ask ourselves, is a book influenced by its writer’s life—how far is it safe to let the man interpret the writer? How far shall we resist or give way to the sympathies and antipathies that the man himself rouses in us—so sensitive are words, so receptive of the character of the author? These are questions that press upon us when we read lives and letters, and we must answer them for ourselves, for nothing can be more fatal than to be guided by the preferences of others in a matter so personal.

But also we can read such books with another aim, not to throw light on literature, not to become familiar with famous people, but to refresh and exercise our own creative powers. Is there not an open window on the right hand of the bookcase? How delightful to stop reading and look out! How stimulating the scene is, in its unconsciousness, its irrelevance, its perpetual movement—the colts galloping round the field, the woman filling her pail at the well, the donkey throwing back his head and emitting his long, acrid moan. The greater part of any library is nothing but the record of such fleeting moments in the lives of men, women, and donkeys. Every literature, as it grows old, has its rubbish-heap, its record of vanished moments and forgotten lives told in faltering and feeble accents that have perished. But if you give yourself up to the delight of rubbish-reading you will be surprised, indeed you will be overcome, by the relics of human life that have been cast out to molder. It may be one letter—but what a vision it gives! It may be a few sentences—but what vistas they suggest! Sometimes a whole story will come together with such beautiful humor and pathos and completeness that it seems as if a great novelist had been at work, yet it is only an old actor, Tate Wilkinson, remembering the strange story of Captain Jones; it is only a young subaltern serving under Arthur Wellesley and falling in love with a pretty girl at Lisbon; it is only Maria Allen letting fall her sewing in the empty drawing-room and sighing how she wishes she had taken Dr Burney’s good advice and had never eloped with her Rishy. None of this has any value; it is negligible in the extreme; yet how absorbing it is now and again to go through the rubbish-heaps and find rings and scissors and broken noses buried in the huge past and try to piece them together while the colt gallops round the field, the woman fills her pail at the well, and the donkey brays.

But we tire of rubbish-reading in the long run. We tire of searching for what is needed to complete the half-truth which is all that the Wilkinsons, the Bunburys and the Maria Allens are able to offer us. They had not the artist’s power of mastering and eliminating; they could not tell the whole truth even about their own lives; they have disfigured the story that might have been so shapely. Facts are all that they can offer us, and facts are a very inferior form of fiction. Thus the desire grows upon us to have done with half-statements and approximations; to cease from searching out the minute shades of human character, to enjoy the greater abstractness, the purer truth of fiction. Thus we create the mood, intense and generalized, unaware of detail, but stressed by some regular, recurrent beat, whose natural expression is poetry; and that is the time to read poetry when we are almost able to write it.

Western wind, when wilt thou blow?

The small rain down can rain.

Christ, if my love were in my arms,

And I in my bed again!

The impact of poetry is so hard and direct that for the moment there is no other sensation except that of the poem itself. What profound depths we visit then—how sudden and complete is our immersion! There is nothing here to catch hold of; nothing to stay us in our flight. The illusion of fiction is gradual; its effects are prepared; but who when they read these four lines stops to ask who wrote them, or conjures up the thought of Donne’s house or Sidney’s secretary; or enmeshes them in the intricacy of the past and the succession of generations? The poet is always our contemporary. Our being for the moment is centered and constricted, as in any violent shock of personal emotion. Afterwards, it is true, the sensation begins to spread in wider rings through our minds; remoter senses are reached; these begin to sound and to comment and we are aware of echoes and reflections. The intensity of poetry covers an immense range of emotion. We have only to compare the force and directness of

I shall fall like a tree, and find my grave,

Only remembering that I grieve,

with the wavering modulation of

Minutes are numbered by the fall of sands,

As by an hour glass; the span of time

Doth waste us to our graves, and we look on it;

An age of pleasure, revelled out, comes home

At last, and ends in sorrow; but the life,

Weary of riot, numbers every sand,

Wailing in sighs, until the last drop down,

So to conclude calamity in rest

or place the meditative calm of

whether we be young or old,

Our destiny, our being’s heart and home,

Is with infinitude, and only there;

With hope it is, hope that can never die,

Effort, and expectation, and desire,

And effort evermore about to be,

beside the complete and inexhaustible loveliness of

The moving Moon went up the sky,

And nowhere did abide:

Softly she was going up,

And a star or two beside—

or the splendid fantasy of

And the woodland haunter

Shall not cease to saunter

When, far down some glade,

Of the great world’s burning,

One soft flame upturning

Seems to his discerning,

Crocus in the shade,

to bethink us of the varied art of the poet; his power to make us at once actors and spectators; his power to run his hand into characters as if it were a glove, and be Falstaff or Lear; his power to condense, to widen, to state, once and for ever.

“We have only to compare”—with those words the cat is out of the bag, and the true complexity of reading is admitted. The first process, to receive impressions with the utmost understanding, is only half the process of reading; it must be completed, if we are to get the whole pleasure from a book, by another. We must pass judgment upon these multitudinous impressions; we must make of these fleeting shapes one that is hard and lasting. But not directly. Wait for the dust of reading to settle; for the conflict and the questioning to die down; walk, talk, pull the dead petals from a rose, or fall asleep. Then suddenly without our willing it, for it is thus that Nature undertakes these transitions, the book will return, but differently. It will float to the top of the mind as a whole. And the book as a whole is different from the book received currently in separate phrases. Details now fit themselves into their places. We see the shape from start to finish; it is a barn, a pig-sty, or a cathedral. Now then we can compare book with book as we compare building with building. But this act of comparison means that our attitude has changed; we are no longer the friends of the writer, but his judges; and just as we cannot be too sympathetic as friends, so as judges we cannot be too severe. Are they not criminals, books that have wasted our time and sympathy; are they not the most insidious enemies of society, corrupters, defilers, the writers of false books, faked books, books that fill the air with decay and disease? Let us then be severe in our judgments; let us compare each book with the greatest of its kind. There they hang in the mind the shapes of the books we have read solidified by the judgments we have passed on them—Robinson Crusoe, Emma The Return of the Native. Compare the novels with these—even the latest and least of novels has a right to be judged with the best. And so with poetry when the intoxication of rhythm has died down and the splendor of words has faded, a visionary shape will return to us and this must be compared with Lear, with Phèdre, with The Prelude; or if not with these, with whatever is the best or seems to us to be the best in its own kind. And we may be sure that the newness of new poetry and fiction is its most superficial quality and that we have only to alter slightly, not to recast, the standards by which we have judged the old.

It would be foolish, then, to pretend that the second part of reading, to judge, to compare, is as simple as the first—to open the mind wide to the fast flocking of innumerable impressions. To continue reading without the book before you, to hold one shadow-shape against another, to have read widely enough and with enough understanding to make such comparisons alive and illuminating—that is difficult; it is still more difficult to press further and to say, “Not only is the book of this sort, but it is of this value; here it fails; here it succeeds; this is bad; that is good.” To carry out this part of a reader’s duty needs such imagination, insight, and learning that it is hard to conceive any one mind sufficiently endowed; impossible for the most self-confident to find more than the seeds of such powers in himself. Would it not be wiser, then, to remit this part of reading and to allow the critics, the gowned and furred authorities of the library, to decide the question of the book’s absolute value for us? Yet how impossible! We may stress the value of sympathy; we may try to sink our own identity as we read. But we know that we cannot sympathize wholly or immerse ourselves wholly; there is always a demon in us who whispers, “I hate, I love,” and we cannot silence him. Indeed, it is precisely because we hate and we love that our relation with the poets and novelists is so intimate that we find the presence of another person intolerable. And even if the results are abhorrent and our judgments are wrong, still our taste, the nerve of sensation that sends shocks through us, is our chief illuminant; we learn through feeling; we cannot suppress our own idiosyncrasy without impoverishing it. But as time goes on perhaps we can train our taste; perhaps we can make it submit to some control. When it has fed greedily and lavishly upon books of all sorts—poetry, fiction, history, biography—and has stopped reading and looked for long spaces upon the variety, the incongruity of the living world, we shall find that it is changing a little; it is not so greedy, it is more reflective. It will begin to bring us not merely judgments on particular books, but it will tell us that there is a quality common to certain books. Listen, it will say, what shall we call this? And it will read us perhaps Lear and then perhaps the Agamemnon in order to bring out that common quality. Thus, with our taste to guide us, we shall venture beyond the particular book in search of qualities that group books together; we shall give them names and thus frame a rule that brings order into our perceptions. We shall gain a further and a rarer pleasure from that discrimination. But as a rule only lives when it is perpetually broken by contact with the books themselves—nothing is easier and more stultifying than to make rules which exists out of touch with facts, in a vacuum—now at last, in order to steady ourselves in this difficult attempt, it may be well to turn to the very rare writers who are able to enlighten us upon literature as an art. Coleridge and Dryden and Johnson, in their considered criticism, the poets and novelists themselves in their unconsidered sayings, are often surprisingly relevant; they light up and solidify the vague ideas that have been tumbling in the misty depths of our minds. But they are only able to help us if we come to them laden with questions and suggestions won honestly in the course of our own reading. They can do nothing for us if we herd ourselves under their authority and lie down like sheep in the shade of a hedge. We can only understand their ruling when it comes in conflict with our own and vanquishes it.

If this is so, if to read a book as it should be read calls for the rarest qualities of imagination, insight, and judgment, and you may perhaps conclude that literature is a very complex art and that it is unlikely that we shall be able, even after a lifetime of reading, to make any valuable contribution to its criticism. We must remain readers; we shall not put on the further glory that belongs to those rare beings who are also critics. But still we have our responsibilities as readers and even our importance. The standards we raise and the judgments we pass steal into the air and become part of the atmosphere which writers breathe as they work. An influence is created which tells upon them even if it never finds its way into print. And that influence, if it were well instructed, vigorous and individual and sincere, might be of great value now when criticism is necessarily in abeyance; when books pass in review like the procession of animals in a shooting gallery, and the critic has only one second in which to load and aim and shoot and may well be pardoned if he mistakes rabbits for tigers, eagles for barndoor fowls, or misses altogether and wastes his shot upon some peaceful cow grazing in a further field. If behind the erratic gunfire of the press the author felt that there was another kind of criticism, the opinion of people reading for the love of reading, slowly and unprofessionally, and judging with great sympathy and yet with great severity, might this not improve the quality of his work? And if by our means books were to become stronger, richer, and more varied, that would be an end worth reaching.

Yet who reads to bring about an end, however desirable? Are there not some pursuits that we practice because they are good in themselves, and some pleasures that are final? And is not this among them? I have sometimes dreamt, at least that when the Day of judgment dawns and the great conquerors and lawyers and statesmen come to receive their rewards—their crowns, their laurels, their names carved indelibly upon imperishable marble—the Almighty will turn to Peter and will say, not without a certain envy when He sees us coming with our books under our arms, “Look, these need no reward. We have nothing to give them here. They have loved reading.”

Virgina Woolf

(The Common Reader, Second Series 1926)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Libraries in Literature, The Art of Reading, Woolf, Virginia

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

Together and Apart

Mrs. Dalloway introduced them, saying you will like him. The conversation began some minutes before anything was said, for both Mr. Serle and Miss Arming looked at the sky and in both of their minds the sky went on pouring its meaning though very differently, until the presence of Mr. Serle by her side became so distinct to Miss Anning that she could not see the sky, simply, itself, any more, but the sky shored up by the tall body, dark eyes, grey hair, clasped hands, the stern melancholy (but she had been told “falsely melancholy”) face of Roderick Serle, and, knowing how foolish it was, she yet felt impelled to say:

“What a beautiful night!”

Foolish! Idiotically foolish! But if one mayn’t be foolish at the age of forty in the presence of the sky, which makes the wisest imbecile—mere wisps of straw—she and Mr. Serle atoms, motes, standing there at Mrs. Dalloway’s window, and their lives, seen by moonlight, as long as an insect’s and no more important.

“Well!” said Miss Anning, patting the sofa cushion emphatically. And down he sat beside her. Was he “falsely melancholy,” as they said? Prompted by the sky, which seemed to make it all a little futile—what they said, what they did—she said something perfectly commonplace again:

“There was a Miss Serle who lived at Canterbury when I was a girl there.”

With the sky in his mind, all the tombs of his ancestors immediately appeared to Mr. Serle in a blue romantic light, and his eyes expanding and darkening, he said: “Yes.

“We are originally a Norman family, who came over with the Conqueror. That is a Richard Serle buried in the Cathedral. He was a knight of the garter.”

Miss Arming felt that she had struck accidentally the true man, upon whom the false man was built. Under the influence of the moon (the moon which symbolized man to her, she could see it through a chink of the curtain, and she took dips of the moon) she was capable of saying almost anything and she settled in to disinter the true man who was buried under the false, saying to herself: “On, Stanley, on”—which was a watchword of hers, a secret spur, or scourge such as middle–aged people often make to flagellate some inveterate vice, hers being a deplorable timidity, or rather indolence, for it was not so much that she lacked courage, but lacked energy, especially in talking to men, who frightened her rather, and so often her talks petered out into dull commonplaces, and she had very few men friends—very few intimate friends at all, she thought, but after all, did she want them? No. She had Sarah, Arthur, the cottage, the chow and, of course THAT, she thought, dipping herself, sousing herself, even as she sat on the sofa beside Mr. Serle, in THAT, in the sense she had coming home of something collected there, a cluster of miracles, which she could not believe other people had (since it was she only who had Arthur, Sarah, the cottage, and the chow), but she soused herself again in the deep satisfactory possession, feeling that what with this and the moon (music that was, the moon), she could afford to leave this man and that pride of his in the Serles buried. No! That was the danger—she must not sink into torpidity—not at her age. “On, Stanley, on,” she said to herself, and asked him:

“Do you know Canterbury yourself?”

Did he know Canterbury! Mr. Serle smiled, thinking how absurd a question it was—how little she knew, this nice quiet woman who played some instrument and seemed intelligent and had good eyes, and was wearing a very nice old necklace—knew what it meant. To be asked if he knew Canterbury. When the best years of his life, all his memories, things he had never been able to tell anybody, but had tried to write—ah, had tried to write (and he sighed) all had centred in Canterbury; it made him laugh.

His sigh and then his laugh, his melancholy and his humour, made people like him, and he knew it, and vet being liked had not made up for the disappointment, and if he sponged on the liking people had for him (paying long calls on sympathetic ladies, long, long calls), it was half bitterly, for he had never done a tenth part of what he could have done, and had dreamed of doing, as a boy in Canterbury. With a stranger he felt a renewal of hope because they could not say that he had not done what he had promised, and yielding to his charm would give him a fresh startat fifty! She had touched the spring. Fields and flowers and grey buildings dripped down into his mind, formed silver drops on the gaunt, dark walls of his mind and dripped down. With such an image his poems often began. He felt the desire to make images now, sitting by this quiet woman.

“Yes, I know Canterbury,” he said reminiscently, sentimentally, inviting, Miss Anning felt, discreet questions, and that was what made him interesting to so many people, and it was this extraordinary facility and responsiveness to talk on his part that had been his undoing, so he thought often, taking his studs out and putting his keys and small change on the dressing–table after one of these parties (and he went out sometimes almost every night in the season), and, going down to breakfast, becoming quite different, grumpy, unpleasant at breakfast to his wife, who was an invalid, and never went out, but had old friends to see her sometimes, women friends for the most part, interested in Indian philosophy and different cures and different doctors, which Roderick Serle snubbed off by some caustic remark too clever for her to meet, except by gentle expostulations and a tear or two—he had failed, he often thought, because he could not cut himself off utterly from society and the company of women, which was so necessary to him, and write. He had involved himself too deep in life—and here he would cross his knees (all his movements were a little unconventional and distinguished) and not blame himself, but put the blame off upon the richness of his nature, which he compared favourably with Wordsworth’s, for example, and, since he had given so much to people, he felt, resting his head on his hands, they in their turn should help him, and this was the prelude, tremulous, fascinating, exciting, to talk; and images bubbled up in his mind.

“She’s like a fruit tree—like a flowering cherry tree,” he said, looking at a youngish woman with fine white hair. It was a nice sort of image, Ruth Anning thought—rather nice, yet she did not feel sure that she liked this distinguished, melancholy man with his gestures; and it’s odd, she thought, how one’s feelings are influenced. She did not like HIM, though she rather liked that comparison of his of a woman to a cherry tree. Fibres of her were floated capriciously this way and that, like the tentacles of a sea anemone, now thrilled, now snubbed, and her brain, miles away, cool and distant, up in the air, received messages which it would sum up in time so that, when people talked about Roderick Serle (and he was a bit of a figure) she would say unhesitatingly: “I like him,” or “I don’t like him,” and her opinion would be made up for ever. An odd thought; a solemn thought; throwing a green light on what human fellowship consisted of.

“It’s odd that you should know Canterbury,” said Mr. Serle. “It’s always a shock,” he went on (the white–haired lady having passed), “when one meets someone” (they had never met before), “by chance, as it were, who touches the fringe of what has meant a great deal to oneself, touches accidentally, for I suppose Canterbury was nothing but a nice old town to you. So you stayed there one summer with an aunt?” (That was all Ruth Anning was going to tell him about her visit to Canterbury.) “And you saw the sights and went away and never thought of it again.”

Let him think so; not liking him, she wanted him to run away with an absurd idea of her. For really, her three months in Canterbury had been amazing. She remembered to the last detail, though it was merely a chance visit, going to see Miss Charlotte Serle, an acquaintance of her aunt’s. Even now she could repeat Miss Serle’s very words about the thunder. “Whenever I wake, or hear thunder in the night, I think ‘Someone has been killed’.” And she could see the hard, hairy, diamond–patterned carpet, and the twinkling, suffused, brown eyes of the elderly lady, holding the teacup out unfilled, while she said that about the thunder. And always she saw Canterbury, all thundercloud and livid apple blossom, and the long grey backs of the buildings.

The thunder roused her from her plethoric middleaged swoon of indifference; “On, Stanley, on,” she said to herself; that is, this man shall not glide away from me, like everybody else, on this false assumption; I will tell him the truth.

“I loved Canterbury,” she said.

He kindled instantly. It was his gift, his fault, his destiny.

“Loved it,” he repeated. “I can see that you did.”

Her tentacles sent back the message that Roderick Serle was nice.

Their eyes met; collided rather, for each felt that behind the eyes the secluded being, who sits in darkness while his shallow agile companion does all the tumbling and beckoning, and keeps the show going, suddenly stood erect; flung off his cloak; confronted the other. It was alarming; it was terrific. They were elderly and burnished into a glowing smoothness, so that Roderick Serle would go, perhaps to a dozen parties in a season, and feel nothing out of the common, or only sentimental regrets, and the desire for pretty images—like this of the flowering cherry tree—and all the time there stagnated in him unstirred a sort of superiority to his company, a sense of untapped resources, which sent him back home dissatisfied with life, with himself, yawning, empty, capricious. But now, quite suddenly, like a white bolt in a mist (but this image forged itself with the inevitability of lightning and loomed up), there it had happened; the old ecstasy of life; its invincible assault; for it was unpleasant, at the same time that it rejoiced and rejuvenated and filled the veins and nerves with threads of ice and fire; it was terrifying. “Canterbury twenty years ago,” said Miss Anning, as one lays a shade over an intense light, or covers some burning peach with a green leaf, for it is too strong, too ripe, too full.

Sometimes she wished she had married. Sometimes the cool peace of middle life, with its automatic devices for shielding mind and body from bruises, seemed to her, compared with the thunder and the livid appleblossom of Canterbury, base. She could imagine something different, more like lightning, more intense. She could imagine some physical sensation. She could imagine——

And, strangely enough, for she had never seen him before, her senses, those tentacles which were thrilled and snubbed, now sent no more messages, now lay quiescent, as if she and Mr. Serle knew each other so perfectly, were, in fact, so closely united that they had only to float side by side down this stream.

Of all things, nothing is so strange as human intercourse, she thought, because of its changes, its extraordinary irrationality, her dislike being now nothing short of the most intense and rapturous love, but directly the word “love” occurred to her, she rejected it, thinking again how obscure the mind was, with its very few words for all these astonishing perceptions, these alternations of pain and pleasure. For how did one name this. That is what she felt now, the withdrawal of human affection, Serle’s disappearance, and the instant need they were both under to cover up what was so desolating and degrading to human nature that everyone tried to bury it decently from sight—this withdrawal, this violation of trust, and, seeking some decent acknowledged and accepted burial form, she said:

“Of course, whatever they may do, they can’t spoil Canterbury.”

He smiled; he accepted it; he crossed his knees the other way about. She did her part; he his. So things came to an end. And over them both came instantly that paralysing blankness of feeling, when nothing bursts from the mind, when its walls appear like slate; when vacancy almost hurts, and the eyes petrified and fixed see the same spot—a pattern, a coal scuttle—with an exactness which is terrifying, since no emotion, no idea, no impression of any kind comes to change it, to modify it, to embellish it, since the fountains of feeling seem sealed and as the mind turns rigid, so does the body; stark, statuesque, so that neither Mr. Serle nor Miss Anning could move or speak, and they felt as if an enchanter had freed them, and spring flushed every vein with streams of life, when Mira Cartwright, tapping Mr. Serle archly on the shoulder, said:

“I saw you at the Meistersinger, and you cut me. Villain,” said Miss Cartwright, “you don’t deserve that I should ever speak to you again.”

And they could separate.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: A Haunted House, and other short stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

A Letter to a Young Poet

My Dear John,

Did you ever meet, or was he before your day, that old gentleman—I forget his name—who used to enliven conversation, especially at breakfast when the post came in, by saying that the art of letter–writing is dead? The penny post, the old gentleman used to say, has killed the art of letter–writing. Nobody, he continued, examining an envelope through his eye–glasses, has the time even to cross their t’s. We rush, he went on, spreading his toast with marmalade, to the telephone. We commit our half–formed thoughts in ungrammatical phrases to the post card. Gray is dead, he continued; Horace Walpole is dead; Madame de Sévigné—she is dead too, I suppose he was about to add, but a fit of choking cut him short, and he had to leave the room before he had time to condemn all the arts, as his pleasure was, to the cemetery. But when the post came in this morning and I opened your letter stuffed with little blue sheets written all over in a cramped but not illegible hand—I regret to say, however, that several t’s were uncrossed and the grammar of one sentence seems to me dubious—I replied after all these years to that elderly necrophilist—Nonsense. The art of letter–writing has only just come into existence. It is the child of the penny post. And there is some truth in that remark, I think. Naturally when a letter cost half a crown to send, it had to prove itself a document of some importance; it was read aloud; it was tied up with green silk; after a certain number of years it was published for the infinite delectation of posterity. But your letter, on the contrary, will have to be burnt. It only cost three–halfpence to send. Therefore you could afford to be intimate, irreticent, indiscreet in the extreme. What you tell me about poor dear C. and his adventure on the Channel boat is deadly private; your ribald jests at the expense of M. would certainly ruin your friendship if they got about; I doubt, too, that posterity, unless it is much quicker in the wit than I expect, could follow the line of your thought from the roof which leaks (“splash, splash, splash into the soap dish”) past Mrs. Gape, the charwoman, whose retort to the greengrocer gives me the keenest pleasure, via Miss Curtis and her odd confidence on the steps of the omnibus; to Siamese cats (“Wrap their noses in an old stocking my Aunt says if they howl”); so to the value of criticism to a writer; so to Donne; so to Gerard Hopkins; so to tombstones; so to gold–fish; and so with a sudden alarming swoop to “Do write and tell me where poetry’s going, or if it’s dead?” No, your letter, because it is a true letter—one that can neither be read aloud now, nor printed in time to come—will have to be burnt. Posterity must live upon Walpole and Madame de Sévigné. The great age of letter–writing, which is, of course, the present, will leave no letters behind it. And in making my reply there is only one question that I can answer or attempt to answer in public; about poetry and its death.

But before I begin, I must own up to those defects, both natural and acquired, which, as you will find, distort and invalidate all that I have to say about poetry. The lack of a sound university training has always made it impossible for me to distinguish between an iambic and a dactyl, and if this were not enough to condemn one for ever, the practice of prose has bred in me, as in most prose writers, a foolish jealousy, a righteous indignation—anyhow, an emotion which the critic should be without. For how, we despised prose writers ask when we get together, could one say what one meant and observe the rules of poetry? Conceive dragging in “blade” because one had mentioned “maid”; and pairing “sorrow” with “borrow”? Rhyme is not only childish, but dishonest, we prose writers say. Then we go on to say, And look at their rules! How easy to be a poet! How strait the path is for them, and how strict! This you must do; this you must not. I would rather be a child and walk in a crocodile down a suburban path than write poetry, I have heard prose writers say. It must be like taking the veil and entering a religious order—observing the rites and rigours of metre. That explains why they repeat the same thing over and over again. Whereas we prose writers (I am only telling you the sort of nonsense prose writers talk when they are alone) are masters of language, not its slaves; nobody can teach us; nobody can coerce us; we say what we mean; we have the whole of life for our province. We are the creators, we are the explorers. . . . So we run on—nonsensically enough, I must admit.

Now that I have made a clean breast of these deficiencies, let us proceed. From certain phrases in your letter I gather that you think that poetry is in a parlous way, and that your case as a poet in this particular autumn Of 1931 is a great deal harder than Shakespeare’s, Dryden’s, Pope’s, or Tennyson’s. In fact it is the hardest case that has ever been known. Here you give me an opening, which I am prompt to seize, for a little lecture. Never think yourself singular, never think your own case much harder than other people’s. I admit that the age we live in makes this difficult. For the first time in history there are readers—a large body of people, occupied in business, in sport, in nursing their grandfathers, in tying up parcels behind counters—they all read now; and they want to be told how to read and what to read; and their teachers—the reviewers, the lecturers, the broadcasters—must in all humanity make reading easy for them; assure them that literature is violent and exciting, full of heroes and villains; of hostile forces perpetually in conflict; of fields strewn with bones; of solitary victors riding off on white horses wrapped in black cloaks to meet their death at the turn of the road. A pistol shot rings out. “The age of romance was over. The age of realism had begun”—you know the sort of thing. Now of course writers themselves know very well that there is not a word of truth in all this—there are no battles, and no murders and no defeats and no victories. But as it is of the utmost importance that readers should be amused, writers acquiesce. They dress themselves up. They act their parts. One leads; the other follows. One is romantic, the other realist. One is advanced, the other out of date. There is no harm in it, so long as you take it as a joke, but once you believe in it, once you begin to take yourself seriously as a leader or as a follower, as a modern or as a conservative, then you become a self–conscious, biting, and scratching little animal whose work is not of the slightest value or importance to anybody. Think of yourself rather as something much humbler and less spectacular, but to my mind, far more interesting—a poet in whom live all the poets of the past, from whom all poets in time to come will spring. You have a touch of Chaucer in you, and something of Shakespeare; Dryden, Pope, Tennyson—to mention only the respectable among your ancestors—stir in your blood and sometimes move your pen a little to the right or to the left. In short you are an immensely ancient, complex, and continuous character, for which reason please treat yourself with respect and think twice before you dress up as Guy Fawkes and spring out upon timid old ladies at street corners, threatening death and demanding twopence–halfpenny.

However, as you say that you are in a fix (“it has never been so hard to write poetry as it is to–day and that poetry may be, you think, at its last gasp in England the novelists are doing all the interesting things now”), let me while away the time before the post goes in imagining your state and in hazarding one or two guesses which, since this is a letter, need not be taken too seriously or pressed too far. Let me try to put myself in your place; let me try to imagine, with your letter to help me, what it feels like to be a young poet in the autumn of 1931. (And taking my own advice, I shall treat you not as one poet in particular, but as several poets in one.) On the floor of your mind, then—is it not this that makes you a poet?—rhythm keeps up its perpetual beat. Sometimes it seems to die down to nothing; it lets you eat, sleep, talk like other people. Then again it swells and rises and attempts to sweep all the contents of your mind into one dominant dance. To–night is such an occasion. Although you are alone, and have taken one boot off and are about to undo the other, you cannot go on with the process of undressing, but must instantly write at the bidding of the dance. You snatch pen and paper; you hardly trouble to hold the one or to straighten the other. And while you write, while the first stanzas of the dance are being fastened down, I will withdraw a little and look out of the window. A woman passes, then a man; a car glides to a stop and then—but there is no need to say what I see out of the window, nor indeed is there time, for I am suddenly recalled from my observations by a cry of rage or despair. Your page is crumpled in a ball; your pen sticks upright by the nib in the carpet. If there were a cat to swing or a wife to murder now would be the time. So at least I infer from the ferocity of your expression. You are rasped, jarred, thoroughly out of temper. And if I am to guess the reason, it is, I should say, that the rhythm which was opening and shutting with a force that sent shocks of excitement from your head to your heels has encountered some hard and hostile object upon which it has smashed itself to pieces. Something has worked in which cannot be made into poetry; some foreign body, angular, sharp–edged, gritty, has refused to join in the dance. Obviously, suspicion attaches to Mrs. Gape; she has asked you to make a poem of her; then to Miss Curtis and her confidences on the omnibus; then to C., who has infected you with a wish to tell his story—and a very amusing one it was—in verse. But for some reason you cannot do their bidding. Chaucer could; Shakespeare could; so could Crabbe, Byron, and perhaps Robert Browning. But it is October 1931, and for a long time now poetry has shirked contact with—what shall we call it?—Shall we shortly and no doubt inaccurately call it life? And will you come to my help by guessing what I mean? Well then, it has left all that to the novelist. Here you see how easy it would be for me to write two or three volumes in honour of prose and in mockery of verse; to say how wide and ample is the domain of the one, how starved and stunted the little grove of the other. But it would be simpler and perhaps fairer to check these theories by opening one of the thin books of modern verse that lie on your table. I open and I find myself instantly confused. Here are the common objects of daily prose—the bicycle and the omnibus. Obviously the poet is making his muse face facts. Listen:

Which of you waking early and watching daybreak

Will not hasten in heart, handsome, aware of wonder

At light unleashed, advancing; a leader of movement,

Breaking like surf on turf on road and roof,

Or chasing shadow on downs like whippet racing,

The stilled stone, halting at eyelash barrier,

Enforcing in face a profile, marks of misuse,

Beating impatient and importunate on boudoir shutters

Where the old life is not up yet, with rays

Exploring through rotting floor a dismantled mill—

The old life never to be born again?

Yes, but how will he get through with it? I read on and find:

Whistling as he shuts

His door behind him, travelling to work by tube

Or walking to the park to it to ease the bowels,

and read on and find again

As a boy lately come up from country to town

Returns for the day to his village in EXPENSIVE SHOES—

and so on again to:

Seeking a heaven on earth he chases his shadow,

Loses his capital and his nerve in pursuing

What yachtsmen, explorers, climbers and BUGGERS ARE AFTER.

These lines and the words I have emphasized are enough to confirm me in part of my guess at least. The poet is trying to include Mrs. Gape. He is honestly of opinion that she can be brought into poetry and will do very well there. Poetry, he feels, will be improved by the actual, the colloquial. But though I honour him for the attempt, I doubt that it is wholly successful. I feel a jar. I feel a shock. I feel as if I had stubbed my toe on the corner of the wardrobe. Am I then, I go on to ask, shocked, prudishly and conventionally, by the words themselves? I think not. The shock is literally a shock. The poet as I guess has strained himself to include an emotion that is not domesticated and acclimatized to poetry; the effort has thrown him off his balance; he rights himself, as I am sure I shall find if I turn the page, by a violent recourse to the poetical—he invokes the moon or the nightingale. Anyhow, the transition is sharp. The poem is cracked in the middle. Look, it comes apart in my hands: here is reality on one side, here is beauty on the other; and instead of acquiring a whole object rounded and entire, I am left with broken parts in my hands which, since my reason has been roused and my imagination has not been allowed to take entire possession of me, I contemplate coldly, critically, and with distaste.

Such at least is the hasty analysis I make of my own sensations as a reader; but again I am interrupted. I see that you have overcome your difficulty, whatever it was; the pen is once more in action, and having torn up the first poem you are at work upon another. Now then if I want to understand your state of mind I must invent another explanation to account for this return of fluency. You have dismissed, as I suppose, all sorts of things that would come naturally to your pen if you had been writing prose—the charwoman, the omnibus, the incident on the Channel boat. Your range is restricted—I judge from your expression—concentrated and intensified. I hazard a guess that you are thinking now, not about things in general, but about yourself in particular. There is a fixity, a gloom, yet an inner glow that seem to hint that you are looking within and not without. But in order to consolidate these flimsy guesses about the meaning of an expression on a face, let me open another of the books on your table and check it by what I find there. Again I open at random and read this:

To penetrate that room is my desire,

The extreme attic of the mind, that lies

Just beyond the last bend in the corridor.

Writing I do it. Phrases, poems are keys.

Loving’s another way (but not so sure).

A fire’s in there, I think, there’s truth at last

Deep in a lumber chest. Sometimes I’m near,

But draughts puff out the matches, and I’m lost.

Sometimes I’m lucky, find a key to turn,

Open an inch or two—but always then

A bell rings, someone calls, or cries of “fire”

Arrest my hand when nothing’s known or seen,

And running down the stairs again I mourn.

and then this:

There is a dark room,

The locked and shuttered womb,

Where negative’s made positive.

Another dark room,

The blind and bolted tomb,

Where positives change to negative.

We may not undo that or escape this, who

Have birth and death coiled in our bones,

Nothing we can do

Will sweeten the real rue,

That we begin, and end, with groans.

And then this:

Never being, but always at the edge of Being

My head, like Death mask, is brought into the Sun.

The shadow pointing finger across cheek,

I move lips for tasting, I move hands for touching,

But never am nearer than touching,

Though the spirit leans outward for seeing.

Observing rose, gold, eyes, an admired landscape,

My senses record the act of wishing

Wishing to be

Rose, gold, landscape or another—

Claiming fulfilment in the act of loving.

Since these quotations are chosen at random and I have yet found three different poets writing about nothing, if not about the poet himself, I hold that the chances are that you too are engaged in the same occupation. I conclude that self offers no impediment; self joins in the dance; self lends itself to the rhythm; it is apparently easier to write a poem about oneself than about any other subject. But what does one mean by “oneself”? Not the self that Wordsworth, Keats, and Shelley have described—not the self that loves a woman, or that hates a tyrant, or that broods over the mystery of the world. No, the self that you are engaged in describing is shut out from all that. It is a self that sits alone in the room at night with the blinds drawn. In other words the poet is much less interested in what we have in common than in what he has apart. Hence I suppose the extreme difficulty of these poems—and I have to confess that it would floor me completely to say from one reading or even from two or three what these poems mean. The poet is trying honestly and exactly to describe a world that has perhaps no existence except for one particular person at one particular moment. And the more sincere he is in keeping to the precise outline of the roses and cabbages of his private universe, the more he puzzles us who have agreed in a lazy spirit of compromise to see roses and cabbages as they are seen, more or less, by the twenty–six passengers on the outside of an omnibus. He strains to describe; we strain to see; he flickers his torch; we catch a flying gleam. It is exciting; it is stimulating; but is that a tree, we ask, or is it perhaps an old woman tying up her shoe in the gutter?

Well, then, if there is any truth in what I am saying—if that is you cannot write about the actual, the colloquial, Mrs. Gape or the Channel boat or Miss Curtis on the omnibus, without straining the machine of poetry, if, therefore, you are driven to contemplate landscapes and emotions within and must render visible to the world at large what you alone can see, then indeed yours is a hard case, and poetry, though still breathing—witness these little books—is drawing her breath in short, sharp gasps. Still, consider the symptoms. They are not the symptoms of death in the least. Death in literature, and I need not tell you how often literature has died in this country or in that, comes gracefully, smoothly, quietly. Lines slip easily down the accustomed grooves. The old designs are copied so glibly that we are half inclined to think them original, save for that very glibness. But here the very opposite is happening: here in my first quotation the poet breaks his machine because he will clog it with raw fact. In my second, he is unintelligible because of his desperate determination to tell the truth about himself. Thus I cannot help thinking that though you may be right in talking of the difficulty of the time, you are wrong to despair.

Is there not, alas, good reason to hope? I say “alas” because then I must give my reasons, which are bound to be foolish and certain also to cause pain to the large and highly respectable society of necrophils—Mr. Peabody, and his like—who much prefer death to life and are even now intoning the sacred and comfortable words, Keats is dead, Shelley is dead, Byron is dead. But it is late: necrophily induces slumber; the old gentlemen have fallen asleep over their classics, and if what I am about to say takes a sanguine tone—and for my part I do not believe in poets dying; Keats, Shelley, Byron are alive here in this room in you and you and you—I can take comfort from the thought that my hoping will not disturb their snoring. So to continue—why should not poetry, now that it has so honestly scraped itself free from certain falsities, the wreckage of the great Victorian age, now that it has so sincerely gone down into the mind of the poet and verified its outlines—a work of renovation that has to be done from time to time and was certainly needed, for bad poetry is almost always the result of forgetting oneself—all becomes distorted and impure if you lose sight of that central reality—now, I say, that poetry has done all this, why should it not once more open its eyes, look out of the window and write about other people? Two or three hundred years ago you were always writing about other people. Your pages were crammed with characters of the most opposite and various kinds—Hamlet, Cleopatra, Falstaff. Not only did we go to you for drama, and for the subtleties of human character, but we also went to you, incredible though this now seems, for laughter. You made us roar with laughter. Then later, not more than a hundred years ago, you were lashing our follies, trouncing our hypocrisies, and dashing off the most brilliant of satires. You were Byron, remember; you wrote Don Juan. You were Crabbe also; you took the most sordid details of the lives of peasants for your theme. Clearly therefore you have it in you to deal with a vast variety of subjects; it is only a temporary necessity that has shut you up in one room, alone, by yourself.

But how are you going to get out, into the world of other people? That is your problem now, if I may hazard a guess—to find the right relationship, now that you know yourself, between the self that you know and the world outside. It is a difficult problem. No living poet has, I think, altogether solved it. And there are a thousand voices prophesying despair. Science, they say, has made poetry impossible; there is no poetry in motor cars and wireless. And we have no religion. All is tumultuous and transitional. Therefore, so people say, there can be no relation between the poet and the present age. But surely that is nonsense. These accidents are superficial; they do not go nearly deep enough to destroy the most profound and primitive of instincts, the instinct of rhythm. All you need now is to stand at the window and let your rhythmical sense open and shut, open and shut, boldly and freely, until one thing melts in another, until the taxis are dancing with the daffodils, until a whole has been made from all these separate fragments. I am talking nonsense, I know. What I mean is, summon all your courage, exert all your vigilance, invoke all the gifts that Nature has been induced to bestow. Then let your rhythmical sense wind itself in and out among men and women, omnibuses, sparrows—whatever come along the street—until it has strung them together in one harmonious whole. That perhaps is your task—to find the relation between things that seem incompatible yet have a mysterious affinity, to absorb every experience that comes your way fearlessly and saturate it completely so that your poem is a whole, not a fragment; to re–think human life into poetry and so give us tragedy again and comedy by means of characters not spun out at length in the novelist’s way, but condensed and synthesised in the poet’s way–that is what we look to you to do now. But as I do not know what I mean by rhythm nor what I mean by life, and as most certainly I cannot tell you which objects can properly be combined together in a poem—that is entirely your affair—and as I cannot tell a dactyl from an iambic, and am therefore unable to say how you must modify and expand the rites and ceremonies of your ancient and mysterious art—I will move on to safer ground and turn again to these little books themselves.

When, then, I return to them I am, as I have admitted, filled, not with forebodings of death, but with hopes for the future. But one does not always want to be thinking of the future, if, as sometimes happens, one is living in the present. When I read these poems, now, at the present moment, I find myself—reading, you know, is rather like opening the door to a horde of rebels who swarm out attacking one in twenty places at once—hit, roused, scraped, bared, swung through the air, so that life seems to flash by; then again blinded, knocked on the head—all of which are agreeable sensations for a reader (since nothing is more dismal than to open the door and get no response), and all I believe certain proof that this poet is alive and kicking. And yet mingling with these cries of delight, of jubilation, I record also, as I read, the repetition in the bass of one word intoned over and over again by some malcontent. At last then, silencing the others, I say to this malcontent, “Well, and what do YOU want?” Whereupon he bursts out, rather to my discomfort, “Beauty.” Let me repeat, I take no responsibility for what my senses say when I read; I merely record the fact that there is a malcontent in me who complains that it seems to him odd, considering that English is a mixed language, a rich language; a language unmatched for its sound and colour, for its power of imagery and suggestion—it seems to him odd that these modern poets should write as if they had neither ears nor eyes, neither soles to their feet nor palms to their hands, but only honest enterprising book–fed brains, uni–sexual bodies and—but here I interrupted him. For when it comes to saying that a poet should be bisexual, and that I think is what he was about to say, even I, who have had no scientific training whatsoever, draw the line and tell that voice to be silent.

But how far, if we discount these obvious absurdities, do you think there is truth in this complaint? For my own part now that I have stopped reading, and can see the poems more or less as a whole, I think it is true that the eye and ear are starved of their rights. There is no sense of riches held in reserve behind the admirable exactitude of the lines I have quoted, as there is, for example, behind the exactitude of Mr. Yeats. The poet clings to his one word, his only word, as a drowning man to a spar. And if this is so, I am ready to hazard a reason for it all the more readily because I think it bears out what I have just been saying. The art of writing, and that is perhaps what my malcontent means by “beauty,” the art of having at one’s beck and call every word in the language, of knowing their weights, colours, sounds, associations, and thus making them, as is so necessary in English, suggest more than they can state, can be learnt of course to some extent by reading—it is impossible to read too much; but much more drastically and effectively by imagining that one is not oneself but somebody different. How can you learn to write if you write only about one single person? To take the obvious example. Can you doubt that the reason why Shakespeare knew every sound and syllable in the language and could do precisely what he liked with grammar and syntax, was that Hamlet, Falstaff and Cleopatra rushed him into this knowledge; that the lords, officers, dependants, murderers and common soldiers of the plays insisted that he should say exactly what they felt in the words expressing their feelings? It was they who taught him to write, not the begetter of the Sonnets. So that if you want to satisfy all those senses that rise in a swarm whenever we drop a poem among them—the reason, the imagination, the eyes, the ears, the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet, not to mention a million more that the psychologists have yet to name, you will do well to embark upon a long poem in which people as unlike yourself as possible talk at the tops of their voices. And for heaven’s sake, publish nothing before you are thirty.

That, I am sure, is of very great importance. Most of the faults in the poems I have been reading can be explained, I think, by the fact that they have been exposed to the fierce light of publicity while they were still too young to stand the strain. It has shrivelled them into a skeleton austerity, both emotional and verbal, which should not be characteristic of youth. The poet writes very well; he writes for the eye of a severe and intelligent public; but how much better he would have written if for ten years he had written for no eye but his own! After all, the years from twenty to thirty are years (let me refer to your letter again) of emotional excitement. The rain dripping, a wing flashing, someone passing—the commonest sounds and sights have power to fling one, as I seem to remember, from the heights of rapture to the depths of despair. And if the actual life is thus extreme, the visionary life should be free to follow. Write then, now that you are young, nonsense by the ream. Be silly, be sentimental, imitate Shelley, imitate Samuel Smiles; give the rein to every impulse; commit every fault of style, grammar, taste, and syntax; pour out; tumble over; loose anger, love, satire, in whatever words you can catch, coerce or create, in whatever metre, prose, poetry, or gibberish that comes to hand. Thus you will learn to write. But if you publish, your freedom will be checked; you will be thinking what people will say; you will write for others when you ought only to be writing for yourself. And what point can there be in curbing the wild torrent of spontaneous nonsense which is now, for a few years only, your divine gift in order to publish prim little books of experimental verses? To make money? That, we both know, is out of the question. To get criticism? But you friends will pepper your manuscripts with far more serious and searching criticism than any you will get from the reviewers. As for fame, look I implore you at famous people; see how the waters of dullness spread around them as they enter; observe their pomposity, their prophetic airs; reflect that the greatest poets were anonymous; think how Shakespeare cared nothing for fame; how Donne tossed his poems into the waste–paper basket; write an essay giving a single instance of any modern English writer who has survived the disciples and the admirers, the autograph hunters and the interviewers, the dinners and the luncheons, the celebrations and the commemorations with which English society so effectively stops the mouths of its singers and silences their songs.