Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

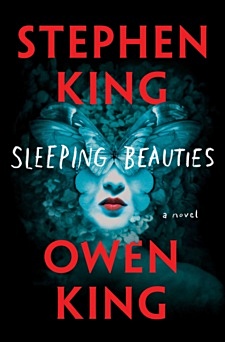

In this spectacular father/son collaboration, Stephen King and Owen King tell the highest of high-stakes stories: what might happen if women disappeared from the world of men?

In a future so real and near it might be now, something happens when women go to sleep; they become shrouded in a cocoon-like gauze. If they are awakened, if the gauze wrapping their bodies is disturbed or violated, the women become feral and spectacularly violent; and while they sleep they go to another place… The men of our world are abandoned, left to their increasingly primal devices. One woman, however, the mysterious Evie, is immune to the blessing or curse of the sleeping disease. Is Evie a medical anomaly to be studied? Or is she a demon who must be slain? Set in a small Appalachian town whose primary employer is a women’s prison, Sleeping Beauties is a wildly provocative, gloriously absorbing father/son collaboration between Stephen King and Owen King.

In a future so real and near it might be now, something happens when women go to sleep; they become shrouded in a cocoon-like gauze. If they are awakened, if the gauze wrapping their bodies is disturbed or violated, the women become feral and spectacularly violent; and while they sleep they go to another place… The men of our world are abandoned, left to their increasingly primal devices. One woman, however, the mysterious Evie, is immune to the blessing or curse of the sleeping disease. Is Evie a medical anomaly to be studied? Or is she a demon who must be slain? Set in a small Appalachian town whose primary employer is a women’s prison, Sleeping Beauties is a wildly provocative, gloriously absorbing father/son collaboration between Stephen King and Owen King.

Sleeping Beauties

A Novel

by Stephen King and Owen King

hardcover

Scribner publisher

720 pages

ISBN 9781501163401

September 2017

List Price $32.50

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, Stephen King, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

The Invisible Girl

The Invisible Girl

by Mary Shelley

This slender narrative has no pretensions o the regularity of a story, or the development of situations and feelings; it is but a slight sketch, delivered nearly as it was narrated to me by one of the humblest of the actors concerned: nor will I spin out a circumstance interesting principally from its singularity and truth, but narrate, as concisely as I can, how I was surprised on visiting what seemed a ruined tower, crowning a bleak promontory overhanging the sea, that flows between Wales and Ireland, to find that though the exterior preserved all the savage rudeness that betokened many a war with the elements, the interior was fitted up somewhat in the guise of a summer-house, for it was too small to deserve any other name.

It consisted but of the ground-floor, which served as an entrance, and one room above, which was reached by a staircase made out of the thickness of the wall. This chamber was floored and carpeted, decorated with elegant furniture; and, above all, to attract the attention and excite curiosity, there hung over the chimney-piece — for to preserve the apartment from damp a fire-place had been built evidently since it had assumed a guise so dissimilar to the object of its construction — a picture simply painted in water-colours, which seemed more than any part of the adornments of the room to be at war with the rudeness of the building, the solitude in which it was placed, and the desolation of the surrounding scenery. This drawing represented a lovely girl in the very pride and bloom of youth; her dress was simple, in the fashion of the day — (remember, reader, I write at the beginning of the eighteenth century), her countenance was embellished by a look of mingled innocence and intelligence, to which was added the imprint of serenity of soul and natural cheerfulness. She was reading one of those folio romances which have so long been the delight of the enthusiastic and young; her mandoline was at her feet — her parroquet perched on a huge mirror near her; the arrangement of furniture and hangings gave token of a luxurious dwelling, and her attire also evidently that of home and privacy, yet bore with it an appearance of ease and girlish ornament, as if she wished to please. Beneath this picture was inscribed in golden letters, “The Invisible Girl.”

Rambling about a country nearly uninhabited, having lost my way, and being overtaken by a shower, I had lighted on this dreary looking tenement, which seemed to rock in the blast, and to be hung up there as the very symbol of desolation. I was gazing wistfully and cursing inwardly my stars which led me to a ruin that could afford no shelter, though the storm began to pelt more seriously than before, when I saw an old woman’s head popped out from a kind of loophole, and as suddenly withdrawn: — a minute after a feminine voice called to me from within, and penetrating a little brambly maze that skreened a door, which I had not before observed, so skilfully had the planter succeeded in concealing art with nature I found the good dame standing on the threshold and inviting me to take refuge within. “I had just come up from our cot hard by,” she said, “to look after the things, as I do every day, when the rain came on — will ye walk up till it is over?” I was about to observe that the cot hard by, at the venture of a few rain drops, was better than a ruined tower, and to ask my kind hostess whether “the things” were pigeons or crows that she was come to look after, when the matting of the floor and the carpeting of the staircase struck my eye. I was still more surprised when I saw the room above; and beyond all, the picture and its singular inscription, naming her invisible, whom the painter had coloured forth into very agreeable visibility, awakened my most lively curiosity: the result of this, of my.exceeding politeness towards the old woman, and her own natural garrulity, was a kind of garbled narrative which my imagination eked out, and future inquiries rectified, till it assumed the following form.

Some years before in the afternoon of a September day, which, though tolerably fair, gave many tokens of a tempestuous evening, a gentleman arrived at a little coast town about ten miles from this place; he expressed his desire to hire a boat to carry him to the town of about fifteen miles further on the coast. The menaces which the sky held forth made the fishermen loathe to venture, till at length two, one the father of a numerous family, bribed by the bountiful reward the stranger promised — the other, the son of my hostess, induced by youthful daring, agreed to undertake the voyage. The wind was fair, and they hoped to make good way before nightfall, and to get into port ere the rising of the storm. They pushed off with good cheer, at least the fishermen did; as for the stranger, the deep mourning which he wore was not half so black as the melancholy that wrapt his mind. He looked as if he had never smiled — as if some unutterable thought, dark as night and bitter as death, had built its nest within his bosom, and brooded therein eternally; he did not mention his name; but one of the villagers recognised him as Henry Vernon, the son of a baronet who possessed a mansion about three miles distant from the town for which be was bound. This mansion was almost abandoned by the family; but Henry had, in a romantic fit, visited it about three years before, and Sir Peter had been down there during the previous spring for about a couple of months.

The boat did not make so much way as was expected; the breeze failed them as they got out to sea, and they were fain with oar as well as sail, to try to weather the promontory that jutted out between them and the spot they desired to reach. They were yet far distant when the shifting wind began to exert its strength, and to blow with violent though unequal puffs. Night came on pitchy dark, and the howling waves rose and broke with frightful violence, menacing to overwhelm the tiny bark that dared resist their fury. They were forced to lower every sail, and take to their oars; one man was obliged to bale out the water, and Vernon himself took an oar, and rowing with desperate energy, equalled the force of the more practised boatmen. There had been much talk between the sailors before the tempest came on; now, except a brief command, all were silent. One thought of his wife and children, and silently cursed the caprice of the stranger that endangered in its effects, not only his life, but their welfare; the other feared less, for he was a daring lad, but he worked hard, and had no time for speech; while Vernon bitterly regretting the thoughtlessness which had made him cause others to share a peril, unimportant as far as he himself was concerned, now tried to cheer them with a voice full of animation and courage, and now pulled yet more strongly at the oar he held. The only person who did not seem wholly intent on the work he was about, was the man who baled; every now and then he gazed intently round, as if the sea held afar off, on its tumultuous waste, some object that he strained his eyes to discern. But all was blank, except as the crests of the high waves showed themselves, or far out on the verge of the horizon, a kind of lifting of the clouds betokened greater violence for the blast. At length he exclaimed — “Yes, I see it! — the larboard oar! — now! if we can make yonder light, we are saved!” Both the rowers instinctively turned their heads, — but cheerless darkness answered their gaze.

“You cannot see it,” cried their companion, ‘but we are nearing it; and, please God, we shall outlive this night.” Soon he took the oar from Vernon’s hand, who, quite exhausted, was failing in his strokes. He rose and looked for the beacon which promised them safety; — it glimmered with so faint a ray, that now he said, “I see it;” and again, “it is nothing:” still, as they made way, it dawned upon his sight, growing more steady and distinct as it beamed across the lurid waters,.which themselves be came smoother, so that safety seemed to arise from the bosom of the ocean under the influence of that flickering gleam.

“What beacon is it that helps us at our need?” asked Vernon, as the men, now able to manage their oars with greater ease, found breath to answer his question.

“A fairy one, I believe,” replied the elder sailor, “yet no less a true: it burns in an old tumble-down tower, built on the top of a rock which looks over the sea. We never saw it before this summer; and now each night it is to be seen, — at least when it is looked for, for we cannot see it from our village; — and it is such an out of the way place that no one has need to go near it, except through a chance like this. Some say it is burnt by witches, some say by smugglers; but this I know, two parties have been to search, and found nothing but the bare walls of the tower.

All is deserted by day, and dark by night; for no light was to be seen while we were there, though it burned sprightly enough when we were out at sea.

“I have heard say,” observed the younger sailor, “it is burnt by the ghost of a maiden who lost her sweetheart in these parts; he being wrecked, and his body found at the foot of the tower: she goes by the name among us of the ‘Invisible Girl.'”

The voyagers had now reached the landing-place at the foot of the tower. Vernon cast a glance upward, — the light was still burning. With some difficulty, struggling with the breakers, and blinded by night, they contrived to get their little bark to shore, and to draw her up on the beach:

they then scrambled up the precipitous pathway, overgrown by weeds and underwood, and, guided by the more experienced fishermen, they found the entrance to the tower, door or gate there was none, and all was dark as the tomb, and silent and almost as cold as death.

“This will never do,” said Vernon; “surely our hostess will show her light, if not herself, and guide our darkling steps by some sign of life and comfort.”

“We will get to the upper chamber,” said the sailor, “if I can but hit upon the broken down steps: but you will find no trace of the Invisible Girl nor her light either, I warrant.”

“Truly a romantic adventure of the most disagreeable kind,” muttered Vernon, as he stumbled over the unequal ground: “she of the beacon-light must be both ugly and old, or she would not be so peevish and inhospitable.”

With considerable difficulty, and, after divers knocks and bruises, the adventurers at length succeeded in reaching the upper story; but all was blank and bare, and they were fain to stretch themselves on the hard floor, when weariness, both of mind and body, conduced to steep their senses in sleep.

Long and sound were the slumbers of the mariners. Vernon but forgot himself for an hour; then, throwing off drowsiness, and finding his roughcouch uncongenial to repose, he got up and placed himself at the hole that served for a window, for glass there was none, and there being not even a rough bench, he leant his back against the embrasure, as the only rest he could find. He had forgotten his danger, the mysterious beacon, and its invisible guardian: his thoughts were occupied on the horrors of his own fate, and the unspeakable wretchedness that sat like a night-mare on his heart.

It would require a good-sized volume to relate the causes which had changed the once happy Vernon into the most woeful mourner that ever clung to the outer trappings of grief, as slight though cherished symbols of the wretchedness within. Henry was the only child of Sir Peter Vernon, and as much spoiled by his father’s idolatry as the old baronet’s violent and tyrannical temper would permit. A young orphan was educated in his father’s house, who in the same way was treated with generosity and kindness, and yet who lived in deep awe of Sir Peter’s authority, who was a widower; and these two children were all he had to exert his power over, or to whom.to extend his affection. Rosina was a cheerful-tempered girl, a little timid, and careful to avoid displeasing her protector; but so docile, so kind-hearted, and so affectionate, that she felt even less than Henry the discordant spirit of his parent. It is a tale often told; they were playmates and companions in childhood, and lovers in after days. Rosina was frightened to imagine that this secret affection, and the vows they pledged, might be disapproved of by Sir Peter. But sometimes she consoled herself by thinking that perhaps she was in reality her Henry’s destined bride, brought up with him under the design of their future union; and Henry, while he felt that this was not the case, resolved to wait only until he was of age to declare and accomplish his wishes in making the sweet Rosina his wife. Meanwhile he was careful to avoid premature discovery of his intentions, so to secure his beloved girl from persecution and insult. The old gentleman was very conveniently blind; he lived always in the country, and the lovers spent their lives together, unrebuked and uncontrolled. It was enough that Rosina played on her mandoline, and sang Sir Peter to sleep every day after dinner; she was the sole female in the house above the rank of a servant, and had her own way in the disposal of her time. Even when Sir Peter frowned, her innocent caresses and sweet voice were powerful to smooth the rough current of his temper. If ever human spirit lived in an earthly paradise, Rosina did at this time: her pure love was made happy by Henry’s constant presence; and the confidence they felt in each other, and the security with which they looked forward to the future, rendered their path one of roses under a cloudless sky. Sir Peter was the slight drawback that only rendered their tête — à — tête more delightful, and gave value to the sympathy they each bestowed on the other. All at once an ominous personage made its appearance in Vernon-Place, in the shape of a widow sister of Sir Peter, who, having succeeded in killing her husband and children with the effects of her vile temper, came, like a harpy, greedy for new prey, under her brother’s roof. She too soon detected the attachment of the unsuspicious pair. She made all speed to impart her discovery to her brother, and at once to restrain and inflame his rage. Through her contrivance Henry was suddenly despatched on his travels abroad, that the coast might be clear for the persecution of Rosina; and then the richest of the lovely girl’s many admirers, whom, under Sir Peter’s single reign, she was allowed, nay, almost commanded, to dismiss, so desirous was he of keeping her for his own comfort, was selected, and she was ordered to marry him. The scenes of violence to which she was now exposed, the bitter taunts of the odious Mrs. Bainbridge, and the reckless fury of Sir Peter, were the more frightful and overwhelming from their novelty. To all she could only oppose a silent, tearful, but immutable steadiness of purpose: no threats, no rage could extort from her more than a touching prayer that they would not hate her, because she could not obey.

“There must he something we don’t see under all this,” said Mrs. Bainbridge, “take my word for it, brother, — she corresponds secretly with Henry. Let us take her down to your seat in Wales, where she will have no pensioned beggars to assist her; and we shall see if her spirit be not bent to our purpose.”

Sir Peter consented, and they all three posted down to , — shire, and took up their abode in the solitary and dreary looking house before alluded to as belonging to the family. Here poor Rosina’s sufferings grew intolerable: — before, surrounded by well-known scenes, and in perpetual intercourse with kind and familiar faces, she had not despaired in the end of conquering by her patience the cruelty of her persecutors; — nor had she written to Henry, for his name had not been mentioned by his relatives, nor their attachment alluded to, and she felt an instinctive wish to escape the dangers about her without his being annoyed, or the sacred secret of her love being laid bare, and wronged by the vulgar abuse of his aunt or the bitter curses of his father. But when she was taken to Wales, and made a prisoner in her apartment, when the flinty.mountains about her seemed feebly to imitate the stony hearts she had to deal with, her courage began to fail. The only attendant permitted to approach her was Mrs. Bainbridge’s maid; and under the tutelage of her fiend-like mistress, this woman was used as a decoy to entice the poor prisoner into confidence, and then to be betrayed. The simple, kind-hearted Rosina was a facile dupe, and at last, in the excess of her despair, wrote to Henry, and gave the letter to this woman to be forwarded. The letter in itself would have softened marble; it did not speak of their mutual vows, it but asked him to intercede with his father, that he would restore her to the kind place she had formerly held in his affections, and cease from a cruelty that would destroy her. “For I may die,” wrote the hapless girl, “but marry another — never!” That single word, indeed, had sufficed to betray her secret, had it not been already discovered; as it was, it gave increased fury to Sir Peter, as his sister triumphantly pointed it out to him, for it need hardly be said that while the ink of the address was yet wet, and the seal still warm, Rosina’s letter was carried to this lady. The culprit was summoned before them; what ensued none could tell; for their own sakes the cruel pair tried to palliate their part. Voices were high, and the soft murmur of Rosina’s tone was lost in the howling of Sir Peter and the snarling of his sister. “Out of doors you shall go,” roared the old man; “under my roof you shall not spend another night.” And the words “infamous seductress,” and worse, such as had never met the poor girl’s ear before, were caught by listening servants; and to each angry speech of the baronet, Mrs. Bainbridge added an envenomed point worse than all.

More dead than alive, Rosina was at last dismissed. Whether guided by despair, whether she took Sir Peter’s threats literally, or whether his sister’s orders were more decisive, none knew, but Rosina left the house; a servant saw her cross the park, weeping, and wringing her hands as she went. What became of her none could tell; her disappearance was not disclosed to Sir Peter till the following day, and then he showed by his anxiety to trace her steps and to find her, that his words had been but idle threats. The truth was, that though Sir Peter went to frightful lengths to prevent the marriage of the heir of his house with the portionless orphan, the object of his charity, yet in his heart he loved Rosina, and half his violence to her rose from anger at himself for treating her so ill. Now remorse began to sting him, as messenger after messenger came back without tidings of his victim; he dared not confess his worst fears to himself; and when his inhuman sister, trying to harden her conscience by angry words, cried, “The vile hussy has too surely made away with herself out of revenge to us;” an oath, the most tremendous, and a look sufficient to make even her tremble, commanded her silence. Her conjecture, however, appeared too true: a dark and rushing stream that flowed at the extremity of the park had doubtless received the lovely form, and quenched the life of this unfortunate girl. Sir Peter, when his endeavours to find her proved fruitless, returned to town, haunted by the image of his victim, and forced to acknowledge in his own heart that he would willingly lay down his life, could he see her again, even though it were as the bride of his son — his son, before whose questioning he quailed like the veriest coward; for when Henry was told of the death of Rosina, he suddenly returned from abroad to ask the cause — to visit her grave, and mourn her loss in the groves and valleys which had been the scenes of their mutual happiness. He made a thousand inquiries, and an ominous silence alone replied. Growing more earnest and more anxious, at length he drew from servants and dependants, and his odious aunt herself, the whole dreadful truth. From that moment despair struck his heart, and misery named him her own. He fled from his father’s presence; and the recollection that one whom he ought to revere was guilty of so dark a crime, haunted him, as of old the Eumenides tormented the souls of men given up to their torturings.

His first, his only wish, was to visit Wales, and to learn if any new discovery had been made, and.whether it were possible to recover the mortal remains of the lost Rosina, so to satisfy the unquiet longings of his miserable heart. On this expedition was he bound, when he made his appearance at the village before named; and now in the deserted tower, his thoughts were busy with images of despair and death, and what his beloved one had suffered before her gentle nature had been goaded to such a deed of woe.

While immersed in gloomy reverie, to which the monotonous roaring of the sea made fit accompaniment, hours flew on, and Vernon was at last aware that the light of morning was creeping from out its eastern retreat, and dawning over the wild ocean, which still broke in furious tumult on the rocky beach. His companions now roused themselves, and prepared to depart. The food they had brought with them was damaged by sea water, and their hunger, after hard labour and many hours fasting, had become ravenous. It was impossible to put to sea in their shattered boat; but there stood a fisher’s cot about two miles off, in a recess in the bay, of which the promontory on which the tower stood formed one side, and to this they hastened to repair; they did not spend a second thought on the light which had saved them, nor its cause, but left the ruin in search of a more hospitable asylum. Vernon cast his eves round as he quitted it, but no vestige of an inhabitant met his eye, and he began to persuade himself that the beacon had been a creation of fancy merely. Arriving at the cottage in question, which was inhabited by a fisherman and his family, they made an homely breakfast, and then prepared to return to the tower, to refit their boat, and if possible bring her round. Vernon accompanied them, together with their host and his son. Several questions were asked concerning the Invisible Girl and her light, each agreeing that the apparition was novel, and not one being able to give even an explanation of how the name had become affixed to the unknown cause of this singular appearance; though both of the men of the cottage affirmed that once or twice they had seen a female figure in the adjacent wood, and that now and then a stranger girl made her appearance at another cot a mile off, on the other side of the promontory, and bought bread; they suspected both these to be the same, but could not tell. The inhabitants of the cot, indeed, appeared too stupid even to feel curiosity, and had never made any attempt at discovery. The whole day was spent by the sailors in repairing the boat; and the sound of hammers, and the voices of the men at work, resounded along the coast, mingled with the dashing of the waves. This was no time to explore the ruin for one who whether human or supernatural so evidently withdrew herself from intercourse with every living being. Vernon, however, went over the tower, and searched every nook in vain; the dingy bare walls bore no token of serving as a shelter; and even a little recess in the wall of the staircase, which he had not before observed, was equally empty and desolate.

Quitting the tower, he wandered in the pine wood that surrounded it, and giving up all thought of solving the mystery, was soon engrossed by thoughts that touched his heart more nearly, when suddenly there appeared on the ground at his feet the vision of a slipper. Since Cinderella so tiny a slipper had never been seen; as plain as shoe could speak, it told a tale of elegance, loveliness, and youth. Vernon picked it up; he had often admired Rosina’s singularly small foot, and his first thought was a question whether this little slipper would have fitted it. It was very strange! — it must belong to the Invisible Girl. Then there was a fairy form that kindled that light, a form of such material substance, that its foot needed to be shod; and yet how shod? — with kid so fine, and of shape so exquisite, that it exactly resembled such as Rosina wore! Again the recurrence of the image of the beloved dead came forcibly across him; and a thousand home-felt associations, childish yet sweet, and lover-like though trifling, so filled Vernon’s heart, that he threw himself his length on the ground, and wept more bitterly than ever the miserable fate of the sweet orphan.

In the evening the men quitted their work, and Vernon returned with them to the cot where.they were to sleep, intending to pursue their voyage, weather permitting, the following morning.

Vernon said nothing of his slipper, but returned with his rough associates. Often he looked back; but the tower rose darkly over the dim waves, and no light appeared. Preparations had been made in the cot for their accommodation, and the only bed in it was offered Vernon; but he refused to deprive his hostess, and spreading his cloak on a heap of dry leaves, endeavoured to give himself up to repose. He slept for some hours; and when he awoke, all was still, save that the hard breathing of the sleepers in the same room with him interrupted the silence. He rose, and going to the window, — looked out over the now placid sea towards the mystic tower; the light burning there, sending its slender rays across the waves. Congratulating himself on a circumstance he had not anticipated, Vernon softly left the cottage, and, wrapping his cloak round him, walked with a swift pace round the bay towards the tower. He reached it; still the light was burning. To enter and restore the maiden her shoe, would be but an act of courtesy; and Vernon intended to do this with such caution, as to come unaware, before its wearer could, with her accustomed arts, withdraw herself from his eyes; but, unluckily, while yet making his way up the narrow pathway, his foot dislodged a loose fragment, that fell with crash and sound down the precipice. He sprung forward, on this, to retrieve by speed the advantage he had lost by this unlucky accident. He reached the door; he entered: all was silent, but also all was dark. He paused in the room below; he felt sure that a slight sound met his ear. He ascended the steps, and entered the upper chamber; but blank obscurity met his penetrating gaze, the starless night admitted not even a twilight glimmer through the only aperture. He closed his eyes, to try, on opening them again, to be able to catch some faint, wandering ray on the visual nerve; but it was in vain. He groped round the room: he stood still, and held his breath; and then, listening intently, he felt sure that another occupied the chamber with him, and that its atmosphere was slightly agitated by an-other’s respiration. He remembered the recess in the staircase; but, before he approached it, he spoke: — he hesitated a moment what to say. “I must believe,” he said, ‘that misfortune alone can cause your seclusion; and if the assistance of a man — of a gentleman — “

An exclamation interrupted him; a voice from the grave spoke his name — the accents of Rosina syllabled, “Henry! — is it indeed Henry whom I hear?”

He rushed forward, directed by the sound, and clasped in his arms the living form of his own lamented girl — his own Invisible Girl he called her; for even yet, as he felt her heart beat near his, and as he entwined her waist with his arm, supporting her as she almost sank to the ground with agitation, he could not see her; and, as her sobs prevented her speech, no sense, but the instinctive one that filled his heart with tumultuous gladness, told him that the slender, wasted form he pressed so fondly was the living shadow of the Hebe beauty he had adored.

The morning saw this pair thus strangely restored to each other on the tranquil sea, sailing with a fair wind for L — , whence they were to proceed to Sir Peter’s seat, which, three months before, Rosina had quitted in such agony and terror. The morning light dispelled the shadows that had veiled her, and disclosed the fair person of the Invisible Girl. Altered indeed she was by suffering and woe, but still the same sweet smile played on her lips, and the tender light of her soft blue eyes were all her own. Vernon drew out the slipper, and shoved the cause that had occasioned him to resolve to discover the guardian of the mystic beacon; even now he dared not inquire how she had existed in that desolate spot, or wherefore she had so sedulously avoided observation, when the right thing to have been done was, to have sought him immediately, under whose care, protected by whose love, no danger need be feared. But Rosina shrunk from him as he spoke, and a death-like pallor came over her cheek, as she faintly whispered, ‘Your father’s curse — your father’s dreadful threats!” It appeared, indeed, that Sir Peter’s violence, and the cruelty of Mrs. Bainbridge, had succeeded in impressing Rosina with wild and unvanquishable terror. She had fled from their house without plan or forethought — driven by frantic horror and overwhelming fear, she had left it with scarcely any money, and there seemed to her no possibility of either returning or proceeding onward. She had no friend except Henry in the wide world; whither could she go? — to have sought Henry would have sealed their fates to misery; for, with an oath, Sir Peter had declared he would rather see them both in their coffins than married. After wandering about, hiding by day, and only venturing forth at night, she had come to this deserted tower, which seemed a place of refuge. I low she had lived since then she could hardly tell; — she had lingered in the woods by day, or slept in the vault of the tower, an asylum none were acquainted with or had discovered: by night she burned the pine-cones of the wood, and night was her dearest time; for it seemed to her as if security came with darkness. She was unaware that Sir Peter had left that part of the country, and was terrified lest her hiding-place should be revealed to him. Her only hope was that Henry would return — that Henry would never rest till he had found her. She confessed that the long interval and the approach of winter had visited her with dismay; she feared that, as her strength was failing, and her form wasting to a skeleton, that she might die, and never see her own Henry more.

An illness, indeed, in spite of all his care, followed her restoration to security and the comforts of civilized life; many months went by before the bloom revisiting her cheeks, and her limbs regaining their roundness, she resembled once more the picture drawn of her in her days of bliss, before any visitation of sorrow. It was a copy of this portrait that decorated the tower, the scene of her suffering, in which I had found shelter. Sir Peter, overjoyed to be relieved from the pangs of remorse, and delighted again to see his orphan-ward, whom he really loved, was now as eager as before he had been averse to bless her union with his son: Mrs. Bainbridge they never saw again. But each year they spent a few months in their Welch mansion, the scene of their early wedded happiness, and the spot where again poor Rosina had awoke to life and joy after her cruel persecutions. Henry’s fond care had fitted up the tower, and decorated it as I saw; and often did he come over, with his “Invisible Girl,” to renew, in the very scene of its occurrence, the remembrance of all the incidents which had led to their meeting again, during the shades of night, in that sequestered ruin.

Mary Shelley (1797 – 1851)

The Invisible Girl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Mary Shelley, Shelley, Mary, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

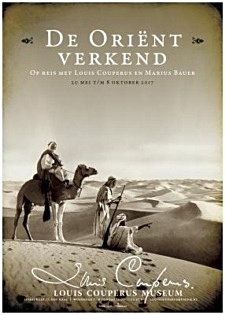

Louis Couperus en Marius Bauer woonden allebei lange tijd in Den Haag, maar kwamen elkaar daar nooit tegen.

Toch waren zij zielsverwanten: zij smachtten beiden naar de pracht en praal van het betoverende Oosten, de sprookjeswereld van Duizend-en-één-nacht. Ter gelegenheid van de honderdvijftigste geboortedag van Marius Bauer organiseert het Louis Couperus Museum alsnog een adembenemende ontmoeting, op de tentoonstelling De Oriënt verkend. Op reis met Louis Couperus en Marius Bauer, van 21 mei t/m 8 oktober 2017.

Toch waren zij zielsverwanten: zij smachtten beiden naar de pracht en praal van het betoverende Oosten, de sprookjeswereld van Duizend-en-één-nacht. Ter gelegenheid van de honderdvijftigste geboortedag van Marius Bauer organiseert het Louis Couperus Museum alsnog een adembenemende ontmoeting, op de tentoonstelling De Oriënt verkend. Op reis met Louis Couperus en Marius Bauer, van 21 mei t/m 8 oktober 2017.

Marius Bauer (1867-1932) werd al in zijn eigen tijd gezien als een formidabel kunstenaar. Op zijn reizen door India, Egypte, Turkije, Rusland, Noord-Afrika en Palestina maakte hij vele schetsen en tekeningen. Die werkte hij thuis uit tot oriëntaalse olieverfschilderijen, etsen en aquarellen die bij het publiek zeer in de smaak vielen. Drie keer bezocht Bauer Algerije, de laatste twee keren begin jaren twintig. Rond diezelfde tijd heeft Louis Couperus (1863-1923) ook in Algerije een half jaar rondgereisd. Hij schreef over de Franse kolonie eenentwintig reisbrieven, die in het weekblad Haagsche Post (en later in boekvorm) zijn verschenen. Net als Bauer zag hij in Algerije veel van zijn oosterse dromen terug. Maar was zijn droom ook bestand tegen de harde realiteit?

Op de tentoonstelling volgen we de reizigers Couperus en Bauer aan de hand van manuscripten, unieke reisdocumenten en oude foto’s, afgewisseld met schetsen, aquarellen en schilderijen van Marius Bauer. In de vitrines liggen ook reisverslagen van tijdgenoten, oude reisgidsen, ansichtkaarten, sieraden en andere kostbare voorwerpen uit de Oriënt, uit zowel museale als particuliere collecties. In de tuinkamer van het museum is een ware Oriëntaalse kamer ingericht.

De Oriënt verkend. Op reis met Louis Couperus en Marius Bauer wordt samengesteld door José Buschman en Willemien de Vlieger-Moll. Bij de tentoonstelling verscheen het boek Couperus in de Oriënt van José Buschman

De oriënt verkend.

Op reis met Louis Couperus en Marius Bauer

21 mei 2017 – 8 oktober 2017

Louis Couperus Museum

Javastraat 17

2585 AB Den Haag

070-3640653

Openingstijden

Woensdag t/m zondag 12.00-17.00 uur

Voor groepen ook op afspraak

# meer info op website louis couperus museum

Nieuwe publicatie door José Buschman:

Nieuwe publicatie door José Buschman:

Couperus in de Oriënt

Ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling De Oriënt verkend. Op reis met Louis Couperus en Marius Bauer in het Louis Couperus Museum heeft José Buschman haar eerdere, veelgeprezen onderzoek Een dandy in de Oriënt. Louis Couperus in Afrika hernieuwd. Met vele onbekende foto’s, recente vondsten en verrassende citaten reconstrueert zij Couperus’ lange tocht door de woestijn.

Door hun levendigheid hebben de reisboeken van Louis Couperus altijd de aandacht getrokken maar het curieuze Met Louis Couperus in Afrika uit 1921 vormt hierop de uitzondering. Couperus reisde zes maanden rond in Algerije en Tunesië, de Haagse schilder Marius Bauer bezocht Noord-Afrika een jaar later. Zijn schetsen ademen de oosterse schoonheid die ook Couperus zo kon bekoren. Anders dan bij Bauer lijkt bij Couperus de oriëntaalse vervoering gaandeweg te zijn verdwenen. Was zijn esthetische kijk wel opgewassen tegen de realiteit van de Franse overheersing, de islam en de armoede?

José Buschman is historica. Zij was medeoprichtster van het Louis Couperus Genootschap. Naast literaire gidsen door het Den Haag van Couperus en F. Bordewijk publiceerde zij Couperus Culinair, de lievelingsgerechten van Louis Couperus.

192 pagina’s

16,8 X 22 cm

ca. 80 afbeeldingen

gebonden met stofomslag

geheel in kleur

vormgeving Bart van den Tooren

Uitg. Bas Lubberhuizen

ISBN 9789059375017

2017, € 19,99

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, Exhibition Archive, Illustrators, Illustration, Louis Couperus, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

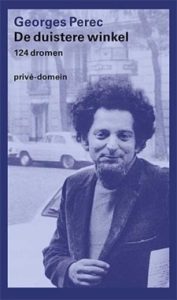

Georges Perec (1936-1982) was ernstig getraumatiseerd door het verdwijnen van zijn ouders tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, en onderging diverse psychoanalytische behandelingen tijdens zijn leven.

Georges Perec (1936-1982) was ernstig getraumatiseerd door het verdwijnen van zijn ouders tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, en onderging diverse psychoanalytische behandelingen tijdens zijn leven.

Het verklaart iets van het belang dat hij hechtte aan zijn dromen, die hij tussen mei 1968 en augustus 1972 noteerde in zijn dagboek, ook om in het reine te komen met een stukgelopen liefde

Perec kwam al doende een nieuwe manier van schrijven op het spoor die een verontrustende intensiteit had. De gefragmenteerde grondstof van nachtelijke hersenspinsels vormt in De duistere winkel een compleet verhaal, gedrenkt in humor en overlopend van stilistische hoogstandjes.

Georges Perec geldt als een van de meest ingenieuze moderne Franse schrijvers. Hij legde zich bij het schrijven vaak bewust formele restricties op. In De dingen bijvoorbeeld wordt geen dialoog gebruikt, wat aan het verhaal een fascinerende, zuiver epische transparantie geeft. Hij liet zich erop voorstaan dat hij nooit twee eendere boeken had geschreven. Toch draagt elk van zijn boeken het onloochenbare stempel van zijn scheppend vernuft.

Van Perec verschenen voortreffelijke vertalingen van de hand van Edu Borger, o.a. Het leven een gebruiksaanwijzing en De dingen.

Georges Perec

De duistere winkel

124 dromen

vertaling Edu Borger

Privé-domein nr 293

Uitgeverij De Arbeiderspers, Amsterdam

ISBN 9789029507554

240 pag. – juni 2017

paperback € 24,99

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Georges Perec, OULIPO (PATAFYSICA), Tales of Mystery & Imagination

The Adventure of The Sussex Vampire

The Adventure of The Sussex Vampire

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Holmes had read carefully a note which the last post had brought him. Then, with the dry chuckle which was his nearest approach to a laugh, he tossed it over to me.

“For a mixture of the modern and the medieval, of the practical and of the wildly fanciful, I think this is surely the limit,” said he. “What do you make of it, Watson?”

I read as follows:

46, OLD JEWRY,

Nov. 19th.

Re Vampires

SIR:

Our client, Mr. Robert Ferguson, of Ferguson and

Muirhead, tea brokers, of Mincing Lane, has made some

inquiry from us in a communication of even date concerning

vampires. As our firm specializes entirely upon the as

sessment of machinery the matter hardly comes within our

purview, and we have therefore recommended Mr. Fergu

son to call upon you and lay the matter before you. We

have not forgotten your successful action in the case of

Matilda Briggs.

We are, sir,

Faithfully yours,

MORRISON, MORRISON, AND DODD.

per E. J. C.

“Matilda Briggs was not the name of a young woman, Watson,” said Holmes in a reminiscent voice. “It was a ship which is associated with the giant rat of Sumatra, a story for which the world is not yet prepared. But what do we know about vampires? Does it come within our purview either? Anything is better than stagnation, but really we seem to have been switched on to a Grimms’ fairy tale. Make a long arm, Watson, and see what V has to say.”

I leaned back and took down the great index volume to which he referred. Holmes balanced it on his knee, and his eyes moved slowly and lovingly over the record of old cases, mixed with the accumulated information of a lifetime.

“Voyage of the Gloria Scott,” he read. “That was a bad business. I have some recollection that you made a record of it, Watson, though I was unable to congratulate you upon the result. Victor Lynch, the forger. Venomous lizard or gila. Remarkable case, that! Vittoria, the circus belle. Vanderbilt and the Yeggman. Vipers. Vigor, the Hammersmith wonder. Hullo! Hullo! Good old index. You can’t beat it. Listen to this, Watson. Vampirism in Hungary. And again, Vampires in Transylvania.” He turned over the pages with eagerness, but after a short intent perusal he threw down the great book with a snarl of disappointment.

“Rubbish, Watson, rubbish! What have we to do with walking corpses who can only be held in their grave by stakes driven through their hearts? It’s pure lunacy.”

“But surely,” said I, “the vampire was not necessarily a dead man? A living person might have the habit. I have read, for example, of the old sucking the blood of the young in order to retain their youth.”

“You are right, Watson. It mentions the legend in one of these references. But are we to give serious attention to such things? This agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain. The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply. I fear that we cannot take Mr. Robert Ferguson very seriously. Possibly this note may be from him and may throw some light upon what is worrying him.”

He took up a second letter which had lain unnoticed upon the table while he had been absorbed with the first. This he began to read with a smile of amusement upon his face which gradually faded away into an expression of intense interest and concentration. When he had finished he sat for some little time lost in thought with the letter dangling from his fingers. Finally, with a start, he aroused himself from his reverie.

“Cheeseman’s, Lamberley. Where is Lamberley, Watson?”

“lt is in Sussex, South of Horsham.”

“Not very far, eh? And Cheeseman’s?”

“I know that country, Holmes. It is full of old houses which are named after the men who built them centuries ago. You get Odley’s and Harvey’s and Carriton’s — the folk are forgotten but their names live in their houses.”

“Precisely,” said Holmes coldly. It was one of the peculiarities of his proud, self-contained nature that though he docketed any fresh information very quietly and accurately in his brain, he seldom made any acknowledgment to the giver. “I rather fancy we shall know a good deal more about Cheeseman’s, Lamberley, before we are through. The letter is, as I had hoped, from Robert Ferguson. By the way, he claims acquaintance with you.”

“With me!”

“You had better read it.”

He handed the letter across. It was headed with the address quoted.

DEAR MR HOLMES [it said]:

I have been recommended to you by my lawyers, but

indeed the matter is so extraordinarily delicate that it is most

difficult to discuss. It concerns a friend for whom I am

acting. This gentleman married some five years ago a Peruvian

lady the daughter of a Peruvian merchant, whom he had

met in connection with the importation of nitrates. The lady

was very beautiful, but the fact of her foreign birth and of

her alien religion always caused a separation of interests and

of feelings between husband and wife, so that after a time

his love may have cooled towards her and he may have

come to regard their union as a mistake. He felt there were

sides of her character which he could never explore or

understand. This was the more painful as she was as loving

a wife as a man could have — to all appearance absolutely

devoted.

Now for the point which I will make more plain when we

meet. Indeed, this note is merely to give you a general idea

of the situation and to ascertain whether you would care to

interest yourself in the matter. The lady began to show

some curious traits quite alien to her ordinarily sweet and

gentle disposition. The gentleman had been married twice

and he had one son by the first wife. This boy was now

fifteen, a very charming and affectionate youth, though

unhappily injured through an accident in childhood. Twice

the wife was caught in the act of assaulting this poor lad in

the most unprovoked way. Once she struck him with a stick

and left a great weal on his arm.

This was a small matter, however, compared with her

conduct to her own child, a dear boy just under one year of

age. On one occasion about a month ago this child had

been left by its nurse for a few minutes. A loud cry from the

baby, as of pain, called the nurse back. As she ran into the

room she saw her employer, the lady, leaning over the baby

and apparently biting his neck. There was a small wound in

the neck from which a stream of blood had escaped. The

nurse was so horrified that she wished to call the husband,

but the lady implored her not to do so and actually gave her

five pounds as a price for her silence. No explanation was

ever given, and for the moment the matter was passed over.

It left, however, a terrible impression upon the nurse’s

mind, and from that time she began to watch her mistress

closely and to keep a closer guard upon the baby, whom she

tenderly loved. It seemed to her that even as she watched

the mother, so the mother watched her, and that every time

she was compelled to leave the baby alone the mother was

waiting to get at it. Day and night the nurse covered the

child, and day and night the silent, watchful mother seemed

to be lying in wait as a wolf waits for a lamb. It must read

most incredible to you, and yet I beg you to take it seri

ously, for a child’s life and a man’s sanity may depend

upon it.

At last there came one dreadful day when the facts could

no longer be concealed from the husband. The nurse’s nerve

had given way; she could stand the strain no longer, and

she made a clean breast of it all to the man. To him it

seemed as wild a tale as it may now seem to you.He knew

his wife to be a loving wife, and, save for the assaults

upon her stepson, a loving mother. Why, then, should

she wound her own dear little baby? He told the nurse that

she was dreaming, that her suspicions were those of a

lunatic, and that such libels upon her mistress were not to be

tolerated. While they were talking a sudden cry of pain was

heard. Nurse and master rushed together to the nursery.

Imagine his feelings, Mr. Holmes, as he saw his wife rise

from a kneeling position beside the cot and saw blood upon

the child’s exposed neck and upon the sheet. With a cry of

horror, he turned his wife’s face to the light and saw blood

all round her lips. It was she — she beyond all question –

who had drunk the poor baby’s blood.

So the matter stands. She is now confined to her room.

There has been no explanation. The husband is half de

mented. He knows, and I know, little of vampirism beyond

the name. We had thought it was some wild tale of foreign

parts. And yet here in the very heart of the English Sussex –

well, all this can be discussed with you in the morning. Will

you see me? Will you use your great powers in aiding a

distracted man? If so, kindly wire to Ferguson, Cheeseman’s,

Lamberley, and I will be at your rooms by ten o’clock.

Yours faithfully,

ROBERT FERGUSON

P. S. I believe your friend Watson played Rugby for

Blackheath when I was three-quarter for Richmond. It is the

only personal introduction which I can give.

“Of course I remembered him,” said I as I laid down the letter. “Big Bob Ferguson, the finest three-quarter Richmond ever had. He was always a good-natured chap. It’s like him to be so concerned over a friend’s case.”

Holmes looked at me thoughtfully and shook his head.

“I never get your limits, Watson,” said he. “There are unexplored possibilities about you. Take a wire down, like a good fellow. ‘Will examine your case with pleasure.’ “

“Your case!”

“We must not let him think that this agency is a home for the weak-minded. Of course it is his case. Send him that wire and let the matter rest till morning.”

Promptly at ten o’clock next morning Ferguson strode into our room. I had remembered him as a long, slab-sided man with loose limbs and a fine turn of speed which had carried him round many an opposing back. There is surely nothing in life more painful than to meet the wreck of a fine athlete whom one has known in his prime. His great frame had fallen in, his flaxen hair was scanty, and his shoulders were bowed. I fear that I roused corresponding emotions in him.

“Hullo, Watson,” said he, and his voice was still deep and hearty. “You don’t look quite the man you did when I threw you over the ropes into the crowd at the Old Deer Park. I expect I have changed a bit also. But it’s this last day or two that has aged me. I see by your telegram, Mr. Holmes, that it is no use my pretending to be anyone’s deputy.” .

“It is simpler to deal direct,” said Holmes.

“Of course it is. But you can imagine how difficult it is when you are speaking of the one woman whom you are bound to protect and help. What can I do? How am I to go to the police with such a story? And yet the kiddies have got to be protected. Is it madness, Mr. Holmes? Is it something in the blood? Have you any similar case in your experience? For God’s sake, give me some advice, for I am at my wit’s end.”

“Very naturally, Mr. Ferguson. Now sit here and pull yourself together and give me a few clear answers. I can assure you that I am very far from being at my wit’s end, and that I am confident we shall find some solution. First of all, tell me what steps you have taken. Is your wife still near the children?”

“We had a dreadful scene. She is a most loving woman, Mr. Holmes. If ever a woman loved a man with all her heart and soul, she loves me. She was cut to the heart that I should have discovered this horrible, this incredible, secret. She would not even speak. She gave no answer to my reproaches, save to gaze at me with a sort of wild, despairing look in her eyes. Then she rushed to her room and locked herself in. Since then she has refused to see me. She has a maid who was with her before her marriage, Dolores by name — a friend rather than a servant. She takes her food to her.”

“Then the child is in no immediate danger?”

“Mrs. Mason, the nurse, has sworn that she will not leave it night or day. I can absolutely trust her. I am more uneasy about poor little Jack, for, as I told you in my note, he has twice been assaulted by her.”

“But never wounded?”

“No, she struck him savagely. It is the more terrible as he is a poor little inoffensive cripple.” Ferguson’s gaunt features softened as he spoke of his boy. “You would think that the dear lad’s condition would soften anyone’s heart. A fall in childhood and a twisted spine, Mr. Holmes. But the dearest, most loving heart within.”

Holmes had picked up the letter of yesterday and was reading it over. “What other inmates are there in your house, Mr. Ferguson?”

“Two servants who have not been long with us. One stablehand, Michael, who sleeps in the house. My wife, myself, my boy Jack, baby, Dolores, and Mrs. Mason. That is all.”

“I gather that you did not know your wife well at the time of your marriage?”

“I had only known her a few weeks.”

“How long had this maid Dolores been with her?”

“Some years.”

“Then your wife’s character would really be better known by Dolores than by you?”

“Yes, you may say so.”

Holmes made a note.

“I fancy,” said he, “that I may be of more use at Lamberley than here. It is eminently a case for personal investigation. If the lady remains in her room, our presence could not annoy or inconvenience her. Of course, we would stay at the inn.”

Ferguson gave a gesture of relief.

“It is what I hoped, Mr. Holmes. There is an excellent train at two from Victoria if you could come.”

“Of course we could come. There is a lull at present. I can give you my undivided energies. Watson, of course, comes with us. But there are one or two points upon which I wish to be very sure before I start. This unhappy lady, as I understand it, has appeared to assault both the children, her own baby and your little son?”

“That is so.”

“But the assaults take different forms, do they not? She has beaten your son.”

“Once with a stick and once very savagely with her hands.”

“Did she give no explanation why she struck him?”

“None save that she hated him. Again and again she said so.”

“Well, that is not unknown among stepmothers. A posthumous jealousy, we will say. Is the lady jealous by nature?”

“Yes, she is very jealous — jealous with all the strength of her fiery tropical love.”

“But the boy — he is fifteen, I understand, and probably very developed in mind, since his body has been circumscribed in action. Did he give you no explanation of these assaults?”

“No, he declared there was no reason.”

“Were they good friends at other times?”

“No, there was never any love between them.”

“Yet you say he is affectionate?”

“Never in the world could there be so devoted a son. My life is his life. He is absorbed in what I say or do.”

Once again Holmes made a note. For some time he sat lost in thought.

“No doubt you and the boy were great comrades before this second marriage. You were thrown very close together, were you not?”

“Very much so.”

“And the boy, having so affectionate a nature, was devoted, no doubt, to the memory of his mother?”

“Most devoted.”

“He would certainly seem to be a most interesting lad. There is one other point about these assaults. Were the strange attacks upon the baby and the assaults upon yow son at the same period?”

“In the first case it was so. It was as if some frenzy had seized her, and she had vented her rage upon both. In the second case it was only Jack who suffered. Mrs. Mason had no complaint to make about the baby.”

“That certainly complicates matters.”

“I don’t quite follow you, Mr. Holmes.”

“Possibly not. One forms provisional theories and waits for time or fuller knowledge to explode them. A bad habit, Mr. Ferguson, but human nature is weak. I fear that your old friend here has given an exaggerated view of my scientific methods. However, I will only say at the present stage that your problem does not appear to me to be insoluble, and that you may expect to find us at Victoria at two o’clock.”

It was evening of a dull, foggy November day when, having left our bags at the Chequers, Lamberley, we drove through the Sussex clay of a long winding lane and finally reached the isolated and ancient farmhouse in which Ferguson dwelt. It was a large, straggling building, very old in the centre, very new at the wings with towering Tudor chimneys and a lichen-spotted, high-pitched roof of Horsham slabs. The doorsteps were worn into curves, and the ancient tiles which lined the porch were marked with the rebus of a cheese and a man after the original builder. Within, the ceilings were corrugated with heavy oaken beams, and the uneven floors sagged into sharp curves. An odour of age and decay pervaded the whole crumbling building.

There was one very large central room into which Ferguson led us. Here, in a huge old-fashioned fireplace with an iron screen behind it dated 1670, there blazed and spluttered a splendid log fire.

The room, as I gazed round, was a most singular mixture of dates and of places. The half-panelled walls may well have belonged to the original yeoman farmer of the seventeenth century. They were ornamented, however, on the lower part by a line of well-chosen modern water-colours; while above, where yellow plaster took the place of oak, there was hung a fine collection of South American utensils and weapons, which had been brought, no doubt, by the Peruvian lady upstairs. Holmes rose, with that quick curiosity which sprang from his eager mind, and examined them with some care. He returned with his eyes full of thought.

“Hullo!” he cried. “Hullo!”

A spaniel had lain in a basket in the corner. It came slowly forward towards its master, walking with difficulty. Its hind legs moved irregularly and its tail was on the ground. It licked Ferguson’s hand.

“What is it, Mr. Holmes?”

“The dog. What’s the matter with it?”

“That’s what puzzled the vet. A sort of paralysis. Spinal meningitis, he thought. But it is passing. He’ll be all right soon — won’t you, Carlo?”

A shiver of assent passed through the drooping tail. The dog’s mournful eyes passed from one of us to the other. He knew that we were discussing his case.

“Did it come on suddenly?”

“In a single night.”

“How long ago?”

“It may have been four months ago.”

“Very remarkable. Very suggestive.”

“What do you see in it, Mr. Holmes?”

“A confirmation of what I had already thought.”

“For God’s sake, what do you think, Mr. Holmes? It may be a mere intellectual puzzle to you, but it is life and death to me! My wife a would-be murderer — my child in constant danger! Don’t play with me, Mr. Holmes. It is too terribly serious.”

The big Rugby three-quarter was trembling all over. Holmes put his hand soothingly upon his arm.

“I fear that there is pain for you, Mr. Ferguson, whatever the solution may be,” said he. “I would spare you all I can. I cannot say more for the instant, but before I leave this house I hope I may have something definite.”

“Please God you may! If you will excuse me, gentlemen, I will go up to my wife’s room and see if there has been any change.”

He was away some minutes, during which Holmes resumed his examination of the curiosities upon the wall. When our host returned it was clear from his downcast face that he had made no progress. He brought with him a tall, slim, brown-faced girl.

“The tea is ready, Dolores,” said Ferguson. “See that your mistress has everything she can wish.”

“She verra ill,” cried the girl, looking with indignant eyes at her master. “She no ask for food. She verra ill. She need doctor. I frightened stay alone with her without doctor.”

Ferguson looked at me with a question in his eyes.

“I should be so glad if I could be of use.”

“Would your mistress see Dr. Watson?”

“I take him. I no ask leave. She needs doctor.”

“Then I’ll come with you at once.”

I followed the girl, who was quivering with strong emotion, up the staircase and down an ancient corridor. At the end was an iron-clamped and massive door. It struck me as I looked at it that if Ferguson tried to force his way to his wife he would find it no easy matter. The girl drew a key from her pocket, and the heavy oaken planks creaked upon their old hinges. I passed in and she swiftly followed, fastening the door behind her.

On the bed a woman was lying who was clearly in a high fever. She was only half conscious, but as I entered she raised a pair of frightened but beautiful eyes and glared at me in apprehension. Seeing a stranger, she appeared to be relieved and sank back with a sigh upon the pillow. I stepped up to her with a few reassuring words, and she lay still while I took her pulse and temperature. Both were high, and yet my impression was that the condition was rather that of mental and nervous excitement than of any actual seizure.

“She lie like that one day, two day. I ‘fraid she die,” said the girl.

The woman turned her flushed and handsome face towards me.

“Where is my husband?”

“He is below and would wish to see you.”

“I will not see him. I will not see him.” Then she seemed to wander off into delirium. “A fiend! A fiend! Oh, what shall I do with this devil?”

“Can I help you in any way?”

“No. No one can help. It is finished. All is destroyed. Do what I will, all is destroyed.”

The woman must have some strange delusion. I could not see honest Bob Ferguson in the character of fiend or devil.

“Madame,” I said, “your husband loves you dearly. He is deeply grieved at this happening.”

Again she turned on me those glorious eyes.

“He loves me. Yes. But do I not love him? Do I not love him even to sacrifice myself rather than break his dear heart? That is how I love him. And yet he could think of me — he could speak of me so.”

“He is full of grief, but he cannot understand.”

“No, he cannot understand. But he should trust.”

“Will you not see him?” I suggested.

“No, no, I cannot forget those terrible words nor the look upon his face. I will not see him. Go now. You can do nothing for me. Tell him only one thing. I want my child. I have a right to my child. That is the only message I can send him.” She turned her face to the wall and would say no more.

I returned to the room downstairs, where Ferguson and Holmes still sat by the fire. Ferguson listened moodily to my account of the interview.

“How can I send her the child?” he said. “How do I know what strange impulse might come upon her? How can I ever forget how she rose from beside it with its blood upon her lips?” He shuddered at the recollection. “The child is safe with Mrs. Mason, and there he must remain.”

A smart maid, the only modern thing which we had seen in the house, had brought in some tea. As she was serving it the door opened and a youth entered the room. He was a remarkable lad, pale-faced and fair-haired, with excitable light blue eyes which blazed into a sudden flame of emotion and joy as they rested upon his father. He rushed forward and threw his arms round his neck with the abandon of a loving girl.

“Oh, daddy,” he cried, “I did not know that you were due yet. I should have been here to meet you. Oh, I am so glad to see you!”

Ferguson gently disengaged himself from the embrace with some little show of embarrassment.

“Dear old chap,” said he, patting the flaxen head with a very tender hand. “I came early because my friends, Mr. Holmes and Dr. Watson, have been persuaded to come down and spend an evening with us.”

“Is that Mr. Holmes, the detective?”

“Yes.”

The youth looked at us with a very penetrating and, as it seemed to me, unfriendly gaze.

“What about your other child, Mr. Ferguson?” asked Holmes. “Might we make the acquaintance of the baby?”

“Ask Mrs. Mason to bring baby down,” said Ferguson. The boy went off with a curious, shambling gait which told my surgical eyes that he was suffering from a weak spine. Presently he returned, and behind him came a tall, gaunt woman bearing in her arms a very beautiful child, dark-eyed, golden-haired, a wonderful mixture of the Saxon and the Latin. Ferguson was evidently devoted to it, for he took it into his arms and fondled it most tenderly.

“Fancy anyone having the heart to hurt him,” he muttered as he glanced down at the small, angry red pucker upon the cherub throat.

It was at this moment that I chanced to glance at Holmes and saw a most singular intentness in his expression. His face was as set as if it had been carved out of old ivory, and his eyes, which had glanced for a moment at father and child, were now fixed with eager curiosity upon something at the other side of the room. Following his gaze I could only guess that he was looking out through the window at the melancholy, dripping garden. It is true that a shutter had half closed outside and obstructed the view, but none the less it was certainly at the window that Holmes was fixing his concentrated attention. Then he smiled, and his eyes came back to the baby. On its chubby neck there was this small puckered mark. Without speaking, Holmes examined it with care. Finally he shook one of the dimpled fists which waved in front of him.

“Good-bye, little man. You have made a strange start in life. Nurse, I should wish to have a word with you in private.”

He took her aside and spoke earnestly for a few minutes. I only heard the last words, which were: “Your anxiety will soon, I hope, be set at rest.” The woman, who seemed to be a sour, silent kind of creature, withdrew with the child.

“What is Mrs. Mason like?” asked Holmes.

“Not very prepossessing externally, as you can see, but a heart of gold, and devoted to the child.”

“Do you like her, Jack?” Holmes turned suddenly upon the boy. His expressive mobile face shadowed over, and he shook his head.

“Jacky has very strong likes and dislikes,” said Ferguson, putting his arm round the boy. “Luckily I am one of his likes.”

The boy cooed and nestled his head upon his father’s breast. Ferguson gently disengaged him.

“Run away, little Jacky,” said he, and he watched his son with loving eyes until he disappeared. “Now, Mr. Holmes,” he continued when the boy was gone, “I really feel that I have brought you on a fool’s errand, for what can you possibly do save give me your sympathy? It must be an exceedingly delicate and complex affair from your point of view.”

“It is certainly delicate,” said my friend with an amused smile, “but I have not been struck up to now with its complexity. It has been a case for intellectual deduction, but when this original intellectual deduction is confirmed point by point by quite a number of independent incidents, then the subjective becomes objective and we can say confidently that we have reached our goal. I had, in fact, reached it before we left Baker Street, and the rest has merely been observation and confirmation.”

Ferguson put his big hand to his furrowed forehead.

“For heaven’s sake, Holmes,” he said hoarsely; “if you can see the truth in this matter, do not keep me in suspense. How do I stand? What shall I do? I care nothing as to how you have found your facts so long as you have really got them.”

“Certainly I owe you an explanation, and you shall have it. But you will permit me to handle the matter in my own way? Is the lady capable of seeing us, Watson?”

“She is ill, but she is quite rational.”

“Very good. It is only in her presence that we can clear the matter up. Let us go up to her.”

“She will not see me,” cried Ferguson.

“Oh, yes, she will,” said Holmes. He scribbled a few lines upon a sheet of paper.”You at least have the entree, Watson. Will you have the goodness to give the lady this note?”

I ascended again and handed the note to Dolores, who cautiously opened the door. A minute later I heard a cry from within, a cry in which joy and surprise seemed to be blended. Dolores looked out.

“She will see them. She will leesten,” said she.

At my summons Ferguson and Holmes came up. As we entered the room Ferguson took a step or two towards his wife, who had raised herself in the bed, but she held out her hand to repulse him. He sank into an armchair, while Holmes seated himself beside him, after bowing to the lady, who looked at him with wide-eyed amazement.

“I think we can dispense with Dolores,” said Holmes. “Oh, very well, madame, if you would rather she stayed I can see no objection. Now, Mr. Ferguson, I am a busy man wlth many calls, and my methods have to be short and direct. The swiftest surgery is the least painful. Let me first say what will ease your mind. Your wife is a very good, a very loving, and a very ill-used woman.”

Ferguson sat up with a cry of joy.

“Prove that, Mr. Holmes, and I am your debtor forever.”

“I will do so, but in doing so I must wound you deeply in another direction.”

“I care nothing so long as you clear my wife. Everything on earth is insignificant compared to that.”

“Let me tell you, then, the train of reasoning which passed through my mind in Baker Street. The idea of a vampire was to me absurd. Such things do not happen in criminal practice in England. And yet your observation was precise. You had seen the lady rise from beside the child’s cot with the blood upon her lips.”

“I did.”

“Did it not occur to you that a bleeding wound may be sucked for some other purpose than to draw the blood from it? Was there not a queen in English history who sucked such a wound to draw poison from it?”

“Poison!”

“A South American household. My instinct felt the presence of those weapons upon the wall before my eyes ever saw them. It might have been other poison, but that was what occurred to me. When I saw that little empty quiver beside the small birdbow, it was just what I expected to see. If the child were pricked with one of those arrows dipped in curare or some other devilish drug, it would mean death if the venom were not sucked out.

“And the dog! If one were to use such a poison, would one not try it first in order to see that it had not lost its power? I did not foresee the dog, but at least I understand him and he fitted into my reconstruction.

“Now do you understand? Your wife feared such an attack. She saw it made and saved the child’s life, and yet she shrank from telling you all the truth, for she knew how you loved the boy and feared lest it break your heart.”

“Jacky!”

“I watched him as you fondled the child just now. His face was clearly reflected in the glass of the window where the shutter formed a background. I saw such jealousy, such cruel hatred, as I have seldom seen in a human face.”

“My Jacky!”

“You have to face it, Mr. Ferguson. It is the more painful because it is a distorted love, a maniacal exaggerated love for you, and possibly for his dead mother, which has prompted his action. His very soul is consumed with hatred for this splendid child, whose health and beauty are a contrast to his own weakness.”

“Good God! It is incredible!”

“Have I spoken the truth, madame?”

The lady was sobbing, with her face buried in the pillows. Now she turned to her husband.

“How could I tell you, Bob? I felt the blow it would be to you. It was better that I should wait and that it should come from some other lips than mine. When this gentleman, who seems to have powers of magic, wrote that he knew all, I was glad.”

“I think a year at sea would be my prescription for Master Jacky,” said Holmes, rising from his chair. “Only one thing is still clouded, madame. We can quite understand your attacks upon Master Jacky. There is a limit to a mother’s patience. But how did you dare to leave the child these last two days?”

“I had told Mrs. Mason. She knew.”

“Exactly. So I imagined.”

Ferguson was standing by the bed, choking, his hands outstretched and quivering.

“This, I fancy, is the time for our exit, Watson,” said Holmes in a whisper. “If you will take one elbow of the too faithful Dolores, I will take the other. There, now,” he added as he closed the door behind him, “I think we may leave them to settle the rest among themselves.”

I have only one further note of this case. It is the letter which Holmes wrote in final answer to that with which the narrative begins. It ran thus:

BAKER STREET,

Nov. 21st.

Re Vampires

SIR:

Referring to your letter of the 19th, I beg to state that I

have looked into the inquiry of your client, Mr. Robert

Ferguson, of Ferguson and Muirhead, tea brokers, of Minc

ing Lane, and that the matter has been brought to a satisfac

tory conclusion. With thanks for your recommendation, I

am, sir,

Faithfully yours,

SHERLOCK HOLMES.

Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

The Adventure of The Sussex Vampire

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan, Sherlock Holmes Theatre, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Rip Van Winkle

Rip Van Winkle

(A Posthumous Writing of Diedrich Knickerbocker)

by Washington Irving

By Woden, God of Saxons,

From whence comes Wensday, that is Wodensday,

Truth is a thing that ever I will keep

Unto thylke day in which I creep into

My sepulchre.

CARTWRIGHT

The following Tale was found among the papers of the late Diedrich Knickerbocker, an old gentleman of New York, who was very curious in the Dutch history of the province, and the manners of the descendants from its primitive settlers. His historical researches, however, did not lie so much among books as among men; for the former are lamentably scanty on his favorite topics; whereas he found the old burghers, and still more their wives, rich in that legendary lore, so invaluable to true history. Whenever, therefore, he happened upon a genuine Dutch family, snugly shut up in its low-roofed farmhouse, under a spreading sycamore, he looked upon it as a little clasped volume of black-letter, and studied it with the zeal of a book-worm.

The result of all these researches was a history of the province during the reign of the Dutch governors, which he published some years since. There have been various opinions as to the literary character of his work, and, to tell the truth, it is not a whit better than it should be. Its chief merit is its scrupulous accuracy, which indeed was a little questioned on its first appearance, but has since been completely established; and it is now admitted into all historical collections, as a book of unquestionable authority.

The old gentleman died shortly after the publication of his work, and now that he is dead and gone, it cannot do much harm to his memory to say that his time might have been better employed in weightier labors. He, however, was apt to ride his hobby his own way; and though it did now and then kick up the dust a little in the eyes of his neighbors, and grieve the spirit of some friends, for whom he felt the truest deference and affection; yet his errors and follies are remembered “more in sorrow than in anger,” and it begins to be suspected, that he never intended to injure or offend. But however his memory may be appreciated by critics, it is still held dear by many folks, whose good opinion is well worth having; particularly by certain biscuit-bakers, who have gone so far as to imprint his likeness on their new-year cakes; and have thus given him a chance for immortality, almost equal to the being stamped on a Waterloo Medal, or a Queen Anne’s Farthing.

* * *

Whoever has made a voyage up the Hudson must remember the Kaatskill mountains. They are a dismembered branch of the great Appalachian family, and are seen away to the west of the river, swelling up to a noble height, and lording it over the surrounding country. Every change of season, every change of weather, indeed, every hour of the day, produces some change in the magical hues and shapes of these mountains, and they are regarded by all the good wives, far and near, as perfect barometers. When the weather is fair and settled, they are clothed in blue and purple, and print their bold outlines on the clear evening sky, but, sometimes, when the rest of the landscape is cloudless, they will gather a hood of gray vapors about their summits, which, in the last rays of the setting sun, will glow and light up like a crown of glory.

At the foot of these fairy mountains, the voyager may have descried the light smoke curling up from a village, whose shingle-roofs gleam among the trees, just where the blue tints of the upland melt away into the fresh green of the nearer landscape. It is a little village of great antiquity, having been founded by some of the Dutch colonists, in the early times of the province, just about the beginning of the government of the good Peter Stuyvesant, (may he rest in peace!) and there were some of the houses of the original settlers standing within a few years, built of small yellow bricks brought from Holland, having latticed windows and gable fronts, surmounted with weather-cocks.