Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Genomineerden E. du Perronprijs 2016: Rodaan Al Galidi, Stefan Hertmans en Carolijn Visser – Arnon Grunberg houdt bij de prijsuitreiking de E. du Perronlezing donderdagavond 13 april 2017 in Tilburg

Genomineerden E. du Perronprijs 2016: Rodaan Al Galidi, Stefan Hertmans en Carolijn Visser – Arnon Grunberg houdt bij de prijsuitreiking de E. du Perronlezing donderdagavond 13 april 2017 in Tilburg

De schrijvers Rodaan Al Galidi, Stefan Hertmans en Carolijn Visser zijn genomineerd voor de E. du Perronprijs 2016. De prijs wordt toegekend aan personen of instellingen die met een cultuuruiting in brede zin een bijdrage leveren aan een beter begrip van de multiculturele samenleving. De uitreiking vindt plaats op donderdagavond 13 april 2017 bij het brabants kenniscentrum kunst en cultuur (bkkc) in Tilburg. Dan houdt Arnon Grunberg de E. du Perronlezing met als titel ‘Het paradijs’.

Rodaan Al Galidi – Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas)

Rodaan Al Galidi – Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas)

Rodaan Al Galidi doet ons verslag van de leerschool die de Nederlandse asielprocedure is. Negen jaar wacht de hoofdpersoon Semmier Kariem op een beschikking in een van de vestigingen van het AZC. Negen jaar tussen aankomst in Nederland op de vlucht voor fysieke bedreiging en definitieve toelating wordt in dit verhaal invoelbaar als een oneindige mentale nekklem. Dat is het leergeld voor vluchtelingen die niet op uitnodiging de landsgrenzen passeren. Leerschool of wachtkamer, het talent van Rodaan Al Galidi is gerijpt. Deze vertellingen in de vorm van brieven aan een geïnteresseerde buitenstaander gericht laten ons alle kanten van hoop, lethargie, opstandigheid, beklag en ironie zien. De bewoners van het AZC leven op een mix van herinneringen, volharding, wanhoop; kortom overlevingsdrift. Het verslag is introspectief, zakelijk, ironisch en soms ronduit Kafkaësk. Met zijn stijl schraagt de verteller zijn bestaan en geeft hij vaart aan een eindeloos vertraagde tijd.

Stefan Hertmans – De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij)

Stefan Hertmans – De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij)

Bekering is een van de meest ingrijpende keuzes die een mens kan maken. Zij rukt het individu uit zijn vertrouwde verband dat bepaald wordt door afstamming en traditie. Toebehoren biedt vertrouwdheid en bescherming. Dit aanbod, deze burcht af te wijzen en te verlaten, te vluchten is een onomkeerbare daad. De bekeerling moet koersen op onbekende instrumenten: een nieuw geloof, een vreemde taal, een onbekend bestaan in een onbekend gebied. Stefan Hertmans voert ons mee in het historische verhaal van Vigdis Adelaïs, die uit liefde besluit een Joodse jongeman te volgen. Het is het einde van de 11e eeuw. Het sentiment van kruistochten hangt in de lucht. Een millennium later volgt Hertmans deze vlucht, fysiek door het landschap met gebruikmaking van bronnen en verbeelding. Verstoting, bedreiging en vlucht zijn van alle tijden. Hertmans is in staat om op heel persoonlijke manier het universele en bijzondere hiervan open te schrijven in een overtuigende roman.

Carolijn Visser – Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus)

Carolijn Visser – Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus)

De titel van deze documentaire vertelling herinnert ons onmiddellijk aan het literaire cliché dat niets zo onwaarschijnlijk is als het leven zelf. Selma, een Joodse overlevende van de Holocaust, besluit met haar Chinese echtgenoot mee te gaan naar China in de jaren vijftig. Wat haar te wachten staat is het lot van intellectuelen en buitenlanders in de periode van de Culturele Revolutie. Het is de verdienste van Carolijn Visser om het onbeschrijfelijke glashelder aan ons te presenteren. Dat doet ze door vaardig te beschrijven wat er aan informatie bewaard is gebleven, maar net zo goed door betekenisvolle leemtes achter te laten. Selma is twee keer slachtoffer geworden van etnische uitsluiting. Ze staat niet voor grotere gehelen, ze was een individu dat voortdurend onder bedreiging van grotere verbanden, ideologieën leefde en uiteindelijk ook vermalen werd. Selma is een monument voor het kwetsbare individu.

E. du Perronprijs

E. du Perronprijs

De E. du Perronprijs is een initiatief van de gemeente Tilburg, de School of Humanities van Tilburg University en brabants kenniscentrum kunst en cultuur (bkkc). De prijs is bedoeld voor personen of instellingen die, net als Du Perron in zijn tijd, grenzen signaleren en doorbreken die wederzijds begrip tussen verschillende bevolkingsgroepen in de weg staan. De prijs bestaat uit een geldbedrag van €2500 euro en een textiel object, ontworpen door [NAAM] en vervaardigd bij het TextielMuseum. In 2015 won Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer de prijs voor zijn dichtbundel Idyllen, zijn pamflet Gelukszoekers en zijn columns in NRC Next. Andere laureaten waren onder meer Warna Oosterbaan & Theo Baart (2014), Mohammed Benzakour (2013), Koen Peeters (2012), Ramsey Nasr (2011), Alice Boot & Rob Woortman (2010), Abdelkader Benali (2009) en Adriaan van Dis (2008).

# Meer informatie over de du Perronprijs op website Tilburg University

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Abdelkader Benali, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Eddy du Perron, Hertmans, Stefan, Literary Events

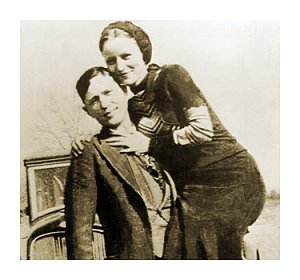

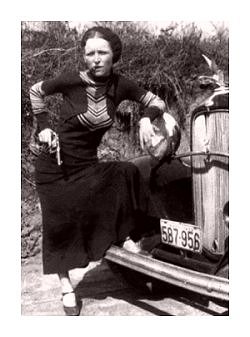

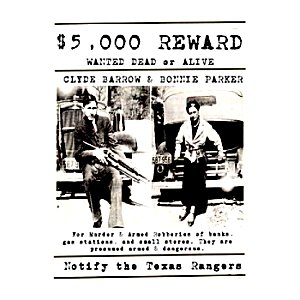

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker

(1910 – 1934)

The Street Girl

You don’t want to marry me honey,

Though just to hear you ask me is sweet;

If you did you’d regret it tomorrow

For I’m only a girl of the street.

Time was when I’d gladly have listened,

Before I was tainted with shame,

But it wouldn’t be fair to you honey;

Men laugh when they mention my name.

Back there on the farm in Nebraska,

I might have said yes to you then,

But I thought the world was a playground;

Just teeming with Santa Claus men.

So I left the old home for the city,

To play in its mad, dirty whirl,

Never knowing how little of pity,

It holds for a slip of a girl.

You think I’m still good-looking honey!

But no I am faded and spent,

Even Helen of Troy would look seedy,

If she followed the pace I went.

But that day I came in from the country,

With my hair down my back in a curl;

Through the length and the breadth of the city,

There was never a prettier girl.

I soon got a job in the chorus,

With nothing but looks and a form,

I had a new man every evening,

And my kisses were thrilling and warm.

I might have sold them for a fortune,

To some old sugar daddy with dough,

But youth called to youth for its lover,

There was plenty that I didn’t know.

Then I fell for the ‘line’ of a ‘junker’,

A slim devotee of hop,

And those dreams in the juice of a poppy;

Had got me before I could stop.

But I didn’t care while he loved me,

Just to lie in his arms was a delight,

But his ardour grew cold and he left me;

In a Chinatown ‘hop-joint’ one night.

Well I didn’t care then what happened,

A Chink took me under his wing,

And down there in a hovel of hell —

I laboured for Hop and Ah-Sing

Oh no I’m no longer a ‘Junker’,

The police came and got me one day,

And I took the one cure that is certain,

That island out there in the bay.

Don’t spring that old gag of reforming,

A girl hardly ever goes back,

Too many are eager and waiting;

To guide her feet off of the track.

A man can break every commandment

And the world will still lend him a hand,

Yet a girl that has loved, but un-wisely

Is an outcast all over the land.

You see how it is don’t you honey,

I’d marry you now if I could,

I’d go with you back to the country,

But I know it won’t do any good,

For I’m only a poor branded woman

And I can’t get away from the past.

Good-bye and God bless you for asking

But I’ll stick out now till the last.

Bonnie (from Bonnie & Clyde) Parker poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker, CRIME & PUNISHMENT

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker

(1910 – 1934)

Outlaws

Billy the Kid and Clyde Barrow

Billy rode on a pinto horse

Billy the Kid I mean

And he met Clyde Barrow riding

In a little gray machine

Billy drew his bridle rein

And Barrow stopped his car

And the dead man talked to the living man

Under the morning star

Billy said to the Barrow boy

Is this the way you ride

In a car that does its ninety per

Machine guns at each side?

I only had my pinto horse

And my six-gun tried and true

I could shoot but they got me

And someday they will get you!

For the men who live like you and me

Are playing a losing game

And the way we shoot, or the way we ride

Is all about the same

And the like of us may never hope

For death to set us free

For the living are always after you

And the dead are after me

Then out of the East arose the sound

Of hoof-beats with the dawn

And Billy pulled his rein and said

I must be moving on

And out of the West came the glare of a light

And the drone of a motor’s song

And Barrow set his foot on the gas

And shouted back, ‘So long’

So into the East, Clyde Barrow rode

And Billy, into the West

The living man who can know no peace

And the dead who can know no rest

Bonnie Parker

Outlaws — Billy the Kid and Clyde Barrow

Billy rode on a pinto horse

Billy the Kid I mean

And he met Clyde Barrow riding

In a little gray machine

Billy drew his bridle rein

And Barrow stopped his car

And the dead man talked to the living man

Under the morning star

Billy said to the Barrow boy

Is this the way you ride

In a car that does its ninety per

Machine guns at each side?

I only had my pinto horse

And my six-gun tried and true

I could shoot but they got me

And someday they will get you!

For the men who live like you and me

Are playing a losing game

And the way we shoot, or the way we ride

Is all about the same

And the like of us may never hope

For death to set us free

For the living are always after you

And the dead are after me

Then out of the East arose the sound

Of hoof-beats with the dawn

And Billy pulled his rein and said

I must be moving on

And out of the West came the glare of a light

And the drone of a motor’s song

And Barrow set his foot on the gas

And shouted back, ‘So long’

So into the East, Clyde Barrow rode

And Billy, into the West

The living man who can know no peace

And the dead who can know no rest

Bonnie Parker poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker, CRIME & PUNISHMENT

In Memory of Bonnie Elizabeth Parker (1910 – 1934)

Today, on 23 May 2014, it is exactly 80 years ago that outlaw Bonnie Parker was killed by the police (together with her friend Clyde Barrow). Bonnie Parker wrote poems since her schooldays.

A man can break every commandment

And the world will still lend him a hand,

Yet a girl that has loved, but un-wisely

Is an outcast all over the land.

Bonnie Parker

(fragment from the poem The Street Girl)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, In Memoriam

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker

(1910 – 1934)

The story of “Suicide Sal”

We each of us have a good “alibi”

For being down here in the “joint”

But few of them really are justified

If you get right down to the point.

You’ve heard of a woman’s glory

Being spent on a “downright cur”

Still you can’t always judge the story

As true, being told by her.

As long as I’ve stayed on this “island”

And heard “confidence tales” from each “gal”

Only one seemed interesting and truthful-

The story of “Suicide Sal”.

Now “Sal” was a gal of rare beauty,

Though her features were coarse and tough;

She never once faltered from duty

To play on the “up and up”.

“Sal” told me this tale on the evening

Before she was turned out “free”

And I’ll do my best to relate it

Just as she told it to me:

I was born on a ranch in Wyoming;

Not treated like Helen of Troy,

I was taught that “rods were rulers”

And “ranked” as a greasy cowboy.

Then I left my old home for the city

To play in its mad dizzy whirl,

Not knowing how little of pity

It holds for a country girl.

There I fell for “the line” of a “henchman”

A “professional killer” from “Chi”

I couldn’t help loving him madly,

For him even I would die.

One year we were desperately happy

Our “ill gotten gains” we spent free,

I was taught the ways of the “underworld”

Jack was just like a “god” to me.

I got on the “F.B.A.” payroll

To get the “inside lay” of the “job”

The bank was “turning big money”!

It looked like a “cinch for the mob”.

Eighty grand without even a “rumble”-

Jack was last with the “loot” in the door,

When the “teller” dead-aimed a revolver

From where they forced him to lie on the floor.

I knew I had only a moment-

He would surely get Jack as he ran,

So I “staged” a “big fade out” beside him

And knocked the forty-five out of his hand.

They “rapped me down big” at the station,

And informed me that I’d get the blame

For the “dramatic stunt” pulled on the “teller”

Looked to them, too much like a “game”.

The “police” called it a “frame-up”

Said it was an “inside job”

But I steadily denied any knowledge

Or dealings with “underworld mobs”.

The “gang” hired a couple of lawyers,

The best “fixers” in any mans town,

But it takes more than lawyers and money

When Uncle Sam starts “shaking you down”.

I was charged as a “scion of gangland”

And tried for my wages of sin,

The “dirty dozen” found me guilty-

From five to fifty years in the pen.

I took the “rap” like good people,

And never one “squawk” did I make

Jack “dropped himself” on the promise

That we make a “sensational break”.

Well, to shorten a sad lengthy story,

Five years have gone over my head

Without even so much as a letter-

At first I thought he was dead.

But not long ago I discovered;

From a gal in the joint named Lyle,

That Jack and his “moll” had “got over”

And were living in true “gangster style”.

If he had returned to me sometime,

Though he hadn’t a cent to give

I’d forget all the hell that he’s caused me,

And love him as long as I lived.

But there’s no chance of his ever coming,

For he and his moll have no fears

But that I will die in this prison,

Or “flatten” this fifty years.

Tommorow I’ll be on the “outside”

And I’ll “drop myself” on it today,

I’ll “bump ’em if they give me the “hotsquat”

On this island out here in the bay…

The iron doors swung wide next morning

For a gruesome woman of waste,

Who at last had a chance to “fix it”

Murder showed in her cynical face.

Not long ago I read in the paper

That a gal on the East Side got “hot”

And when the smoke finally retreated,

Two of gangdom were found “on the spot”.

It related the colorful story

Of a “jilted gangster gal”

Two days later, a “sub-gun” ended

The story of “Suicide Sal”.

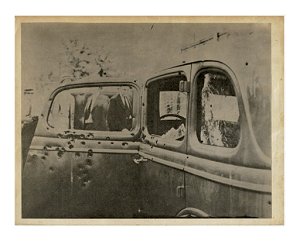

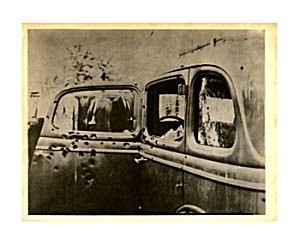

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker (October 1, 1910 – May 23, 1934) and Clyde Chestnut Barrow (March 24, 1909 – May 23, 1934) were well-known (as Bonnie & Clyde) American outlaws and bankrobbers. They were both killed in a police ambush on May 23, 1934. Bonnie Parker wrote most of her poems, while in jail, in a little notebook she had obtained from The First National Bank of Burkburnett, Texas.

Bonnie Parker poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, Suicide, Western Fiction

Bonnie Elizabeth Parker

(1910 – 1934)

The trail’s end

You’ve read the story of Jesse James

of how he lived and died.

If you’re still in need;

of something to read,

here’s the story of Bonnie and Clyde.

Now Bonnie and Clyde are the Barrow gang

I’m sure you all have read.

how they rob and steal;

and those who squeal,

are usually found dying or dead.

There’s lots of untruths to these write-ups;

they’re not as ruthless as that.

their nature is raw;

they hate all the law,

the stool pigeons, spotters and rats.

They call them cold-blooded killers

they say they are heartless and mean.

But I say this with pride

that I once knew Clyde,

when he was honest and upright and clean.

But the law fooled around;

kept taking him down,

and locking him up in a cell.

Till he said to me;

“I’ll never be free,

so I’ll meet a few of them in hell”

The road was so dimly lighted

there were no highway signs to guide.

But they made up their minds;

if all roads were blind,

they wouldn’t give up till they died.

The road gets dimmer and dimmer

sometimes you can hardly see.

But it’s fight man to man

and do all you can,

for they know they can never be free.

From heart-break some people have suffered

from weariness some people have died.

But take it all in all;

our troubles are small,

till we get like Bonnie and Clyde.

If a policeman is killed in Dallas

and they have no clue or guide.

If they can’t find a fiend,

they just wipe their slate clean

and hang it on Bonnie and Clyde.

There’s two crimes committed in America

not accredited to the Barrow mob.

They had no hand;

in the kidnap demand,

nor the Kansas City Depot job.

A newsboy once said to his buddy;

“I wish old Clyde would get jumped.

In these awfull hard times;

we’d make a few dimes,

if five or six cops would get bumped”

The police haven’t got the report yet

but Clyde called me up today.

He said,”Don’t start any fights;

we aren’t working nights,

we’re joining the NRA.”

From Irving to West Dallas viaduct

is known as the Great Divide.

Where the women are kin;

and the men are men,

and they won’t “stool” on Bonnie and Clyde.

If they try to act like citizens

and rent them a nice little flat.

About the third night;

they’re invited to fight,

by a sub-gun’s rat-tat-tat.

They don’t think they’re too smart or desperate

they know that the law always wins.

They’ve been shot at before;

but they do not ignore,

that death is the wages of sin.

Some day they’ll go down together

they’ll bury them side by side.

To few it’ll be grief,

to the law a relief

but it’s death for Bonnie and Clyde.

A few weeks before Bonny Parker was killed by 26 bullets from the police, she wrote this poem which she sent to her mother.

Bonnie Parker poetry

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Bonnie and Clyde, Bonnie Parker, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, Western Fiction

Vlezige mensen, wethouders, poppetjes, kastjes

Welkom iedereen! Het thema van vanavond is: ‘Verlichting’.

De stroming in de 17e en 18e eeuw die ons tot het inzicht heeft laten komen dat de Rede het enige instrument is om tot Waarheid te komen. Weg met het bijgeloof, weg met de onderdrukking van de kerk, weg met het feodale systeem, en op naar grondrechten, gelijkheid en vrijheid waarvoor vervolgens gestreden werd in de Franse Revolutie. Dit alles is uiteraard veroorzaakt door historici, filosofen en ontevreden burgers, maar niet enkel door hen. De Pamflettisten hebben zich een slag in de rondte gewerkt om iedereen te laten weten hoe vreselijk de adel was en dat de koning elke dag baadde in kinderbloed. Zij wisten met opruiende teksten, beschuldigingen, beledigingen en verdachtmakingen de burgerij voor zich te winnen. Ongeacht of de boodschap waarheid bevatte of niet.

Herkenbaar?

Wellicht dat we de pamflettisten van nu vanavond op het podium zullen zien.

Dan zullen we hen vast horen over wethouders van vroeger en van nu, en over andere mensen uit de politiek. Over hoe een of andere handeling van een of ander iemand exemplarisch is voor dit ‘dorp’ en haar mentaliteit.

Het kan ook zijn dat iemand in deze zaal hard wordt aangepakt. Maar niet té hard, het moet natuurlijk wel gezellig en grappig blijven. Maar om het grappig te laten zijn, moet het wel gaan over iemand die wij allemaal (persoonlijk) kennen, anders valt er niets te lachen. Als je dan niet lacht ben je de gebeten hond en dus iemand zonder humor.

Harde uitspraken moeten grappig zijn, anders zijn ze alleen maar pijnlijk! Jongens, lach dan, lach dan!

Het lijkt wel een formule. Een pamfletformule!

Eens kijken, wat zou de formule deze avond kunnen bevatten?

Ik gok dat het woord ‘dorp’ toch wel een aantal keer valt.

Wethouder van Cultuur Marjo Frenk is een goede kansmaker op een naamsvermelding denk ik.

Anton Dautzenberg komt vast weer met een sexuele verdachtmaking van iemand, misschien voormalig stadsdichter Cees van Raak die seks heeft gehad met de hond van Daan Taks? (Nachtdichter van Tilburg.) Wellicht betrekt hij er een landelijke bekendheid in, want dat onderscheid moet uiteraard gemaakt worden! Het onderscheid tussen de landelijke bekendheid versus het provincialisme dat noodzakelijk in die zin betrokken is als je een accent legt op lándelijke bekendheid. Hij wel, verdomme. Dan maar een grapje maken: Poep! Ha. Ha. Ha. Enig!

Misschien houdt Anton (zo mag ik ‘m noemen, zegt ook weer wat over mij, ik ken hem. Dat maakt mij iets meer immuun voor zijn harde uitspraken die mij mogelijk te wachten staan. Wauw!) eerder een betoog over iets met bloed en de nachtburgemeester Godelieve Engbersen. Iets over een moord die gepleegd is waarbij wederom de hond van Daan Taks betrokken was.

Luuk Koelman zal hoe dan ook de woede van heel het land op de hals halen met zijn column, dat moet haast wel. Als je de woede van bijna heel het land al op de hals hebt gehaald, met de column over Mariska Orbán-de Haas, dan moet je toch minstens het hele land boos maken wil je nog opvallen. Maar wij in de zaal zijn ‘insiders on the joke’ dus wij kunnen dan met een gerust hart zeggen dat de rest van het land zo kleinburgerlijk is en nooit iets snapt. “Hoe kun je die ironie nou niet inzien? On-be-grijpelijk”, fluistert ene Lidy uit Tilburg dan tegen haar man Hans; “Wij zijn dan nog behoorlijk open-minded, toch Hans?” “Gelukkig maar.”

Wat maakt het toch zo smakelijk, dat pakken op de persoon, de Ad Hominem?

“Polemiek!” Hoor ik Antonnetje en zijn billemaat Erik Hannema roepen in mijn hoofd.

Ja, polemiek jongens, polemiek! Het is een kunst, dat moet gezegd, maar bedrijf het dan ook! Polemiek betekent redetwisten. Daar hebben we het woord ‘rede’ dus weer. Diezelfde rede die ons tot de waarheid zou kunnen brengen. De twee deelnemers zouden het komen tot waarheid hoog in het vaandel hebben staan, waarom zou je anders redetwisten? Om je gelijk te halen misschien? Zou kunnen, maar een gelijk zonder daadwerkelijk gelijk lijkt mij weinig voldoenend. Misschien wordt deze kunst wel veel bedreven op avonden zoals deze uit een gevoel van nostalgie: “Vroeger kon men dit nog, vroeger was er nog iets om voor te strijden, vroeger waren er nog revoluties in het Westen!” Onrust stoken om mensen op te ruien en te motiveren. Maar, waarom zou je dan mensen persoonlijk pakken met fictieve gebeurtenissen of –verdachtmakingen?

Misschien omdat het te lang bespreken van de ware gebeurtenissen, fouten en terechte verdachtmakingen te pijnlijk en ongemakkelijk is. Het moet wel gezellig blijven en dus worden er een paar fictieve gebeurtenissen tussen de regels geplakt zodat de mogelijkheid dat de ware gebeurtenissen ook fictief zijn nog blijft bestaan.

We willen wel de roddels maar niet de confrontatie, niet echt. We willen alleen de smakelijke sappige details mits ze weinig lijken te zeggen over onszelf. Is ook makkelijker natuurlijk! De ander is gek, de ander is grappig.

Is het waar dat men vroeger dan wel eindeloos opzoek was naar de waarheid? Ik denk het niet, althans, niet meer dan nu. Ten tijde van de Franse Revolutie verzon de lage adel er ook op los, wat er maar nodig was om de burgers aan hun kant te krijgen. Dat dit lukte en uiteindelijk meer vrijheid tot stand bracht is een feit. Al waren de donkere tijden van de middeleeuwen iets minder donker dan zij ons tot op de dag van vandaag hebben doen denken. Maar zij deden dit met gevaar voor eigen leven, niet braaf in een zaal in Tilburg. Waarom zouden wij dan een hang hebben naar die revoluties van vroeger en de pamflettaal die daarmee samenhangt? Welke donkere tijden proberen wij te ontvluchten?

Kijk, Jace vd Ven (eerste stadsdichter van Tilburg) komt uit vroeger, dus hij hoeft het vroeger niet naar nu te trekken. Hij weet al hoe het toen was en kan hoogstens oprecht nostalgische gevoelens ervaren. Juist doordat hij uit vroeger komt weet hij ook dat de geschiedenis zich herhaalt. Hij kan zijn nootjes pakken, naar de show kijken en pogen iets universeels te schrijven als dichter. Want dat kan hij. Jace kan, en misschien wel hierdoor, gedichten maken die buiten de tijd staan. Dat is wat een goed gedicht doet.

Misschien dat Tom America ons nog een vieze film toont, met in een soundscape de naam van Burgermeester Noordanus in herhaling. Of iets met een jong Thais meisje, gespeeld door mij, dan kunnen we dat meteen voor het TilT-festival gebruiken, Tom! Theatermaker Peer de Graaf en dichter Martin Beversluis doen dan samen een interpretatieve dans, naakt uiteraard.

Nu, ik hoop dat u precies vaak genoeg genoemd wordt deze avond om belangrijk gevonden te worden, maar net te weinig om uw ziel ontbloot te voelen.

De formule zal het leren: Pastor Harm Schilder + grapje over piemeltjes van jonge jongens = hihi. Tilburg culturele hoofdstad + iets met de VVD + naamsbekendheid want ik ken d’n dieje – lekker gewoon gebleven = haha.

Deze avond gaat ons hopelijk enorm verlichten. Of de rede hier zegeviert kunt u allen zelf bepalen, we houden na afloop een opiniepeiling in het licht van: ‘uw stem is ook belangrijk’, dit past binnen het thema waar de pamflettisten zo voor gepamfletteerd hebben: Gelijkheid. Het bespotten van de poppetjes kan beginnen!

Het lucht vast wel op, dus in die zin wellicht…. Verlichting.

Esther Porcelijn, 19 jan 2013

(Column voorgedragen tijdens ‘Schuimt’, columnistenbijeenkomst met o.a. Anton Dautzenberg, Luuk Koelman, JACE vd Ven, en Tom America, in jazzpodium Paradox in Tilburg)

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

foto jef van kempen

Esther Porcelijn

NUT(S)

Ja. Ik geef het toe: Ik studeer filosofie. Guilty!! (zoals Peter Griffin het zegt in Family Guy). Ik ben die persoon die het advies van de ouders in de wind geslagen heeft en toch naar de toneelschool is gegaan en daarna naar het Departement Wijsbegeerte aan de UvT.

Ik weet het, je hoeft geen open deuren in te trappen: Ik ben geen advocaat of econoom aan het worden, Ergo: ik word niet erg rijk. Voor sommigen nog Ergoër: Ik volg geen nuttige studie. Ik ben voor velen dé vleeswording van de Linkse Kerk en beoefen dé linkse hobby der linkse hobby’s. Daarbij denken veel mensen dat filosofie vaag en esoterisch is; een studie waar je gewoon wat kletst over van alles en daar een 10 voor krijgt. Dus ik ben ook nog eens een vage linkse hobby-hippie.

Errug!! Pauper plebs. Nog erger misschien wel: Een toekomstige uitkeringstrekker en hoe dan ook een subsidieslurper. Nog Erruger!! Wow!

Op het departement woedt, tussen de studenten, onder leiding van enkelen die de moed echt stevig in de schoenen is gezakt, al een tijd een discussie, of een monoloog.. nee toch een discussie.

Daarin gaat het vaak over het nut van onze studie en van het vak van een filosoof. Tijdens lange gesprekken maakt iemand nét iets te vaak de grap: “Ach, we vinden een baan ondanks de filosofie, niet dankzíj.”

Dan, als iemand het zat wordt gaat het argumentenkanon aan. Nu zou ik de argumenten kunnen opnoemen, bijvoorbeeld dat o.a. Nederlandse politici, Amerikaanse presidenten, beroemde kunstenaars, journalisten en CEO’s van grote bedrijven filosofie hebben gestudeerd, maar dat is anekdotische argumentatie, en we weten allemaal dat een aantal individuele voorbeelden nog geen goed argument maakt.

Ik zou ook kunnen beginnen over hoe de democratie volledig is uitgedacht door filosofen en hoe de vrijheid die wij nu genieten alleen maar kan bestaan doordat een paar goede denkers de grenzen van die vrijheid hebben uitgedacht. Maar dan zou ik mijn professoren klakkeloos napraten, en in het verleden behaalde resultaten bieden geen garantie voor de toekomst, en meer van dat soort powerpoint-uitspraken. Of hoe exacte wetenschap ook niet exact is, voor als iemand beweert dat wat wij doen niet empirisch toetsbaar is en dus maar geklets. Maar dat is ook niks, iemand anders met hetzelfde probleem opzadelen als jijzelf. Misschien zou ik iets kunnen zeggen over communicatie- of vrijetijdswetenschappen, dat die studies pas écht nutteloos zijn, maar daar heeft niemand wat aan, laat staan dat het een argument is voor wat dan ook.

Beter kan ik iets proberen te zeggen, of nee, te duiden, wat betreft de termen ‘links’ en ‘nut’, alleen denk ik dat we daar toch een lang gesprek voor nodig hebben waarin we het vast ook zouden hebben over hoe wat ‘men’ vindt helemaal niet altijd waar hoeft te zijn, en over de invloed van de media en andere joop.nl onderwerpen.

Ik zou mijzelf fiks kunnen verdedigen uit pissigheid waaruit blijkt dat ik mij juist veel aantrek van wat men vindt, meer nog dan die abstracte groep ‘velen’ waar ik het over heb. Ik zou dan als ik echt boos word iets kunnen roepen als: “Alsof jij met je heftige hang naar rijkdom en dikke status echt gelukkig wordt of ook maar ergens verstand van kan hebben.”

Als ik dat zou doen dan zou ik dingen zeggen die ik helemaal niet vind en mij alleen maar meer stereotiep maken dan ik ben. Bovenal zou het de domste drogreden zijn. Ad hominem. Dat is pas echt errug. Ai.

Esther Porcelijn

(27) studeert filosofie aan de Universiteit van Tilburg. Ze is bovendien actrice en stadsdichter. Eerder gepubliceerd in UNIVERS 2012.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

4

Turn the handle; I have turned it. I have kept my word: to the end. But the vengeance that I sought to accomplish upon the obligation imposed on me, as the slave of a machine, to serve up life to my machine as food, life has chosen to turn back upon me. Very good. No one henceforward can deny that I have now arrived at perfection.

As an operator I am now, truly, perfect.

About a month after the appalling disaster which is still being discussed everywhere, I bring these notes to an end.

A pen and a sheet of paper: there is no other way left to me now in which I can communicate with my fellow-men. I have lost my voice; I am dumb now for ever. Elsewhere in these notes I have written: “I suffer from this silence of mine, into which everyone comes, as into a place of certain hospitality. ‘I should like now my silence to close round me altogether’.” Well, it has closed round me. I could not be better qualified to act as the servant of a machine.

But I must tell you the whole story, as it happened.

The wretched fellow went, next morning, to Borgalli to complain forcibly of the ridiculous figure which, as he was informed, Polacco intended to make him cut with these precautions.

He insisted at all costs that the orders should be cancelled, offering to give them all a specimen, if they needed it, of his well-known skill as a marksman. Polacco excused himself to Borgalli, saying that he had taken these measures not from any want of confidence in Nuti’s courage or sureness of eye, but from prudence, knowing Nuti to be extremely nervous, as for that matter he was shewing himself to be at that moment by uttering this excited protest, instead of the grateful, friendly thanks which Polacco had a right to expect from him.

“Besides,” he unfortunately added, pointing to me, “you see, Commendatore, there’s Gubbio here too, who has to go into the cage….”

The poor wretch looked at me with such contempt that I immediately turned upon Polacco, exclaiming:

“No, no, my dear fellow! Don’t bother about me, please! You know very well that I shall go on quietly turning my handle, even if I see this gentleman in the jaws and claws of the beast!”

There was a laugh from the actors who had gathered round to listen; whereupon Polacco shrugged his shoulders and gave way, or pretended to give way. Fortunately for me, as I learned afterwards, he gave secret instructions to Fantappiè and one of the others to conceal their weapons and to stand ready for any emergency. Nuti went off to his dressing-room to put on his sporting clothes; I went to the Negative Department to prepare my machine for its meal. Fortunately for the company, I drew a much larger supply of film than would be required, to judge approximately by the length of the scene. When I returned to the crowded lawn, by the side of the enormous cage, set with a forest scene, the other cage, with the tiger inside it, had already been carried out and placed so that the two cages opened into one another. It only remained to pull up the door of the smaller cage.

Any number of actors from the four companies had assembled on either side, close to the cage, so that they could see between the tree trunks and branches that concealed its bars. I hoped for a moment that the Nestoroff, having secured her object, would at least have had the prudence not to come. But there she was, alas!

She stood apart from the crowd, a little way off, with Carlo Ferro, dressed in bright green, and was smiling as she repeatedly nodded her head in agreement with what Ferro was saying to her, albeit from the grim attitude in which he stood by her side it seemed evident that such a smile was not the appropriate answer to his words. But it was meant for the others, that smile, for all of us who stood watching her, and was also for me, a brighter smile, when I fixed my gaze on her; and it said to me once again that she was not afraid of anything, because the greatest possible evil for her I already knew: she had it by her side–there it was–Ferro; he was her punishment, and to the very end she I was determined, with that smile, to taste its, full flavour in the coarse words which he was probably addressing to her at that moment.

Taking my eyes from her, I sought those of Nuti. They were clouded. Evidently he too had caught sight of the Nestoroff there in the distance; but he chose to pretend that he had not. His face had grown stiff. He made an effort to smile, but smiled with his lips alone, a faint, nervous smile, at what some one was saying to him. With his black velvet cap on his head, with its long peak, his red coat, a huntsman’s brass horn slung over his shoulder, his white buckskin breeches fitting close to his thighs; booted and spurred, rifle in hand: he was ready.

The door of the big cage, through which ha and I were to enter, was opened from outside; to help us to climb in, two stage hands placed a pair of steps beneath it. He entered the cage first, then I. While I was setting up my machine on its tripod, which had been handed to me through the door of the cage, I noticed that Nuti first of all knelt down on the spot marked out for him, then rose and went across to thrust apart the boughs at one side of the cage, as though he were making a loophole there. I alone was in a position to ask him:

“Why?”

But the state of feeling that had grown up between us did not allow of our exchanging a single word at this stage. His action might therefore have been interpreted by me in several ways, which would have left me uncertain at a moment when the most absolute and precise certainty was essential. And then it was just as though Nuti had not moved at all; not only did I not think any more about his action, it was exactly as though I had not even noticed it.

He took his stand on the spot marked out for him, raising his rifle; I gave the signal:

“Ready.”

We heard from the other cage the sound of the door being pulled up. Polacco, perhaps seeing the animal begin to move towards the open door, shouted amid the silence:

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

And I began to turn the handle, with my eyes on the tree trunks in the background, through which the animal’s head was now protruding, lowered, as though peering out to explore the country; I saw that head slowly drawn back, the two forepaws remain firm, close together, and the hindlegs gradually, silently gather strength and the back rise in an arch in readiness for the spring. My hand was impassively keeping the time that I had set for its movement, faster, slower, dead slow, as though my will had flowed down–firm, lucid, inflexible–into my wrist, and from there had assumed entire control, leaving my brain free to think, my heart to feel; so that my hand continued to obey even when with a pang of terror I saw Nuti take his aim from the beast and slowly turn the muzzle of his rifle towards the spot where a moment earlier he had opened a loophole among the boughs, and fire, and the tiger immediately spring upon him and become merged with him, before my eyes, in a horrible writhing mass. Drowning the most deafening shouts that came from all the actors outside the cage as they ran instinctively towards the Nestoroff who had fallen at the shot, drowning the cries of Carlo Ferro, I heard there in the cage the deep growl of the beast and the horrible gasp of the man as he lay helpless in its fangs, in its claws, which were tearing his throat and chest; I heard, I heard, I kept on hearing above that growl, above that gasp, the continuous ticking of the machine, the handle of which my hand, alone, of its own accord, still kept on turning; and I waited for the beast to spring next upon me, having brought him down; and the moments of waiting seemed to me an eternity, and it seemed to me that throughout eternity I had been counting them, as I turned, still turned the handle, powerless to stop, when finally an arm was thrust in between the bars, carrying a revolver, and fired a shot point blank into the tiger’s ear over the mangled corpse of Nuti; and I was pulled back and dragged from the cage with the handle of the machine so tightly clasped in my fist that it was impossible at first to wrest it from me. I uttered no groan, no cry: my voice, from terror, had perished in my throat for ever.

Well, I have rendered the firm a service from which they will reap a fortune. As soon as I was able, I explained to the people who gathered round me terror-struck, first of all by signs, then in writing, that they were to take good care of the machine, which had been wrenched from my hand: that machine had in its maw the life of a man; I had given it that life to eat to the very last, until the moment when that arm had been thrust in to kill the tiger. There was a fortune to be extracted from this film, what with the enormous publicity and the morbid curiosity which the sordid atrocity of the drama of that slaughtered couple would everywhere arouse.

Ah, that it would fall to my lot to feed literally on the life of a man one of the many machines invented by man for his pastime, I could never have guessed. The life which this machine has devoured was naturally no more than it could be in a time like the present, in an age of machines; a production stupid in one aspect, mad in another, inevitably, and in the former more, in the latter rather less stamped with a brand of vulgarity.

I have found salvation, I alone, in my silence, with my silence, which has made me thus–according to the standard of the times–perfect. My friend Simone Pau will not understand this, more and more determined to drown himself in ‘superfluity’, the perpetual inmate of a Casual Shelter. I have already secured a life of ease with the compensation which the firm has given me for the service I have rendered it, and I shall soon be rich with the royalties which have been assigned to me from the hire of the monstrous film. It is true that I shall not know what to do with these riches; but I shall not reveal my embarrassment to anyone; least of all to Simone Pau, who comes every day to shake me, to abuse me, in the hope of forcing me out of this inanimate silence, which makes him furious. He would like to see me weep, would like me at least with my eyes to shew distress or anger; to make him understand by signs that I agree with him, that I too believe that life is there, in that ‘superfluity’ of his. I do not move an eyelid; I sit gazing at him, rigid, motionless, until he flies from the house in a rage. Poor Cavalena, from anoher angle, is studying on my behalf textbooks of nervous pathology, suggests injections and electric batteries, hovers round me to persuade me to agree to a surgical operation on my vocal chords; and Signorina Luisetta, penitent, heartbroken at my calamity, in which she chooses to detect an element of heroism, timidly lets me see now that she would like to hear issue, if not from my lips, at any rate from my heart a “yes” for herself.

No, thank you. Thanks to everybody. I have had enough. I prefer to remain like this. The times are what they are; life is what it is; and in the sense that I give to my profession, I intend to go on as I am–alone, mute and impassive–being the operator.

Is the stage set?

“Are you ready? Shoot….”

THE END

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (34)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

3

And now, God willing, we have reached the end. Nothing remains now save the final picture of the killing of the tiger.

The tiger: yes, I prefer, if I must be distressed, to be distressed over her; and I go to pay her a visit, standing for the last time in front of her cage.

She has grown used to seeing me, the beautiful creature, and does not stir. Only she wrinkles her brows a little, annoyed; but she endures the sight of me as she endures the burden of this sunlit silence, lying heavy round about her, which here in the cage is impregnated with a strong bestial odour. The sunlight enters the cage and she shuts her eyes, perhaps to dream, perhaps so as not to see descending ‘upon her the stripes of shadow cast by the iron bars. Ah, she must be tremendously bored with life also; bored, too, with my pity for her; and I believe that to make it cease, with a fit reward, she would gladly devour me. This desire, which she realises that the bars prevent her from satisfying, makes her heave a deep sigh; and since she is lying outstretched, her languid head drooping on one paw, I see, when she sighs, a cloud of dust rise from the floor of the cage.

Her sigh, really distresses me, albeit I understand why she has emitted it; it is her sorrowful recognition of the deprivation to which she has been condemned of her natural right to devour man, whom she has every reason to regard as her enemy.

“To-morrow,” I tell her. “To-morrow, my dear, this torment will be at an end. It is true that this torment still means something to you, and that, when it is over, nothing will matter to you any more. But if you have to choose between this torment and nothing, perhaps nothing is preferable! A captive like this, far from your savage haunts, powerless to tear anyone to pieces, or even to frighten him, what sort of tiger are you? Hark! They are making ready the big cage out there…. You are accustomed already to hearing these hammer-blows, and pay no attention to them. In this respect, you see, you are more fortunate than man: man may think, when he hears the hammer-blows: ‘There, those are for me; that is the undertaker, getting my coffin ready.’ You are already there, in your coffin, and do not know it: it will be a far larger cage than this; and you will have the comfort of a touch of local colour there too: it will represent a glade in a forest. The cage in which you now are will be carried out there and placed so that it opens into the other. A stage hand will climb on the roof of this cage, and pull up the door, while another man opens the door of the other cage; and you will then steal in between the tree trunks, cautious and wondering. But immediately you will notice a curious ticking noise. Nothing! It will be I, winding my machine on its tripod; yes, I shall be in the cage too, beside you; but don’t pay any attention to me! Do you see? Standing a little way in front of me is another man, another man who takes aim at you and fires, ah! there you are on the ground, a dead weight, brought down in your spring…. I shall come up to you; with no risk to the machine, I shall register your last convulsions, and so good-bye!”

If it ends like that…

This evening, on coming out of the Positive Department, where, in view of Borgalli’s urgency, I have been lending a hand myself in the developing and joining of the sections of this monstrous film, I saw Aldo Nuti advancing upon me with the unusual intention of accompanying me home. I at once observed that he was trying, or rather forcing himself not to let me see that he had something to say to me.

“Are you going home?”

“Yes.”

“So am I.”

When we had gone some distance he asked:

“Have you been in the rehearsal theatre to-day?”

“No. I’ve been working downstairs, in the dark room.”

Silence for a while. Then he made a painful effort to smile, with what he intended for a smile of satisfaction.

“They were trying my scenes. Everyone was pleased with them. I should never have imagined that they would come out so well. One especially.

I wish you could have seen it.”

“Which one?”

“The one that shews me by myself for a minute, close up, with a finger on my lips, like this, engaged in thinking. It lasts a little too long, perhaps… my face is a little too prominent … and my eyes…. You can count my eyelashes. I thought I should never disappear from the screen.”

I turned to look at him; but he at once took refuge in an obvious reflexion:

“Yes!” he said. “Curious the effect our own appearance has on us in a photograph, even on a plain card, when we look at it for the first time. Why is it?”

“Perhaps,” I answered, “because we feel that we are fixed there in a moment of time which no longer exists in ourselves; which will remain, and become steadily more remote.”

“Perhaps!” he sighed. “Always more remote for us….”

“No,” I went on, “for the picture as well. The picture ages too, just as we gradually age. It ages, although it is fixed there for ever in that moment; it ages young, if we are young, because that young man in the picture becomes older year by year with us, in us.”

“I don’t follow you.”

“It is quite easy to understand, if you will think a little. Just listen: the time, there, of the picture, does not advance, does not keep moving on, hour by hour, with us, into the future; you expect it to remain fixed at that point, but it is moving too, in the opposite direction; it recedes farther and farther into the past, that time. Consequently the picture itself is a dead thing which as time goes on recedes gradually farther into the past: and the younger it is the older and more remote it becomes.”

“Ah, yes, I see what you mean…. Yes, yes,” he said. “But there is something sadder still. A picture that has grown old young and empty.”

“How do you mean, empty?”

“The picture of somebody who has died young.”

I again turned to look at him; but he at once added:

“I have a portrait of my father, who died quite young, at about my age; so long ago that I don’t remember him. I have kept it reverently, this picture of him, although it means nothing to me. It has grown old too, yes, receding, as you say, into the past. But time, in ageing the picture, has not aged my father; my father has not lived through this period of time. And he presents himself before me empty, devoid of all the life that for him has not existed; he presents himself before me with his old picture of himself as a young man, which says nothing to me, which cannot say anything to me, because he does not even know that I exist. It is, in fact, a portrait he had made of himself before he married; a portrait, therefore, of a time when he was not my father. I do not exist in him, there, just as all my life has been lived without him.”

“It is sad….”

“Sad, yes. But in every family, in the old photograph albums, on the little table by the sofa in every provincial drawing-room, think of all the faded portraits of people who no longer mean anything to us, of whom we no longer know who they were, what they did, how they died….”

All of a sudden he changed the subject to ask me, with a frown:

“How long can a film be made to last?”

He no longer turned to me as to a person with whom he took pleasure in conversing; but in my capacity as an operator. And the tone of his voice was so different, the expression of his face had so changed that I suddenly felt rise up in me once again that contempt which for some time past I have been cherishing for everything and everybody. Why did he wish to know how long a film could last? Had he attached himself to me to find out this? Or from a desire to make my flesh creep, leaving me to guess that he intended to do something rash that very day, so that our walk together should leave me with a tragic memory or a sense of remorse?

I felt tempted to stop short in front of him and to shout in his face:

“I say, my dear fellow, you can drop all that with me, because I don’t take the slightest interest in you! You can do all the mad things you please, this evening, to-morrow: I shan’t stir! You may perhaps have asked me how long a film can last to make me think that you are leaving behind you that picture of yourself with your finger on your lips? And you think perhaps that you are going to fill the whole world with pity and terror with that enlarged picture, in which ‘they can count your eyelashes’? How long do you expect a film to last?”

I shrugged my shoulders and answered:

“It all depends upon how often it is used.”

He too from the change in my tone must have realised that my attitude towards him had changed also, and he began to look at me in a way that troubled me.

The position was this: he was still here on earth a petty creature. Useless, almost a nonentity; but he existed, and was walking beside me, and was suffering. It was true that he was suffering, like all the rest of us, from life which is the true malady of us all. He was suffering for no worthy reason; but whose fault was it if he had been born so petty? Petty as he was, he was suffering, and his suffering was great for him, however unworthy…. It was from life that he suffered, from one of the innumerable accidents of life, which had fallen upon him to take from him the little that he had in him and rend end destroy him! At the moment he was here, Etili walking by my side, on a June evening, the sweetness of which he could not taste; to-morrow perhaps, since life had so turned against him, he would no longer exist: those legs of his would never be set in motion again to walk; he would never see again this avenue along which we were going; and he would never again clothe his feet in those fine patent leather shoes and those silk socks, would never again take pleasure, even in the height of his desperation, as he stood before the glass of his wardrobe every morning, in the elegance of the faultless coat upon his handsome slim body which I could put out my hand now and touch, still living, conscious, by ray side.

“Brother….”

No, I did not utter that word. There are certain words that we hear, in a fleeting moment; we do not say them. Christ could say them, who was not dressed like me and was not, like me, an operator. Amid a human society which delights in a cinematographic show and tolerates a profession like mine, certain words, certain emotions become ridiculous.

“If I were to call this Signor Nuti ‘brother’,” I thought, “he would take offence; because… I may have taught him a little philosophy as to pictures that grow old, but what am I to him? An operator: a hand that turns a handle.”

He is a “gentleman,” with madness already latent perhaps in the ivory box of his skull, with despair in his heart, but a rich “titled gentleman” who can well remember having known me as a poor student, a humble tutor to Giorgio Mirelli in the villa by Sorrento. He intends to keep the distance between me and himself, and obliges me to keep it too, now, between him and myself: the distance that time and my profession have created. Between him and me, the machine.

“Excuse me,” he asked, just as we were reaching the house, “how will you manage to-morrow about taking the scene of the shooting of the tiger?”

“It is quite easy,” I answered. “I shall be standing behind you.”

“But won’t there be the bars of the cage, all the plants in between?”

“They won’t be in my way. I shall be inside the cage with you.”

He stood and stared at me in surprise:

“You will be inside the cage too?”

“Certainly,” I answered calmly.

“And if… if I were to miss?”

“I know that you are a crack shot. Not that it will make any difference. To-morrow all the actors will be standing round the cage, looking on. Several of them will be armed and ready to fire if you miss.”

He stood for a while lost in thought, as though this information had annoyed him.

Then: “They won’t fire before I do?” he said.

“No, of course not. They will fire if it is necessary.”

“But in that case,” he asked, “why did that fellow… that Signor Ferro insist upon all those conditions, if there is really no danger?”

“Because in Ferro’s case there might perhaps not have been all those others, outside the cage, armed.”

“Ah! Then they are for me? They have taken these precautions for me? How ridiculous! Whose doing is it? Yours, perhaps?”

“Mine, no. What have I got to do with it?”

“How do you know about it, then?”

“Polacco said so.”

“Said so to you? Then it was Polacco? Ah, I shall have something to say to him to-morrow morning! I won’t have it, do you understand? I won’t have it!”

“Are you addressing me?”

“You too!”

“Dear Sir, let me assure you that what you say leaves me perfectly indifferent: hit or miss your tiger; do all the mad things you like inside the cage: I shall not stir a finger, you may be sure of that. Whatever happens, I shall remain quite impassive and go on turning my handle. Bear that in mind, if you please!”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (34)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (33)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

2

Trapped. That is all. This and this only is what Nestoroff wished–that it should be he who entered the cage.

With what object? That seems to me easily understood, after the way in which she has arranged things: that is to say that everyone, first of all, heaping contempt upon Carlo Ferro whom she had persuaded or forced to go away, should insist that there was no danger involved in entering the cage, so that afterwards the challenge of Nuti’s offer to enter it should seem all the more ridiculous, and, by the laughter with which that challenge was greeted, the other’s self-esteem might emerge if not unscathed still with the least possible damage; with no damage at all, indeed, since, with the malign satisfaction which people feel on seeing a poor bird caught in a snare, that the snare in question was not a pleasant thing everyone is now prepared to admit; all the more credit, therefore, to Ferro who has managed to free himself from it at this sparrow’s expense. In short, this to my mind is clearly what she wished: to take in Nuti, by shewing him her heartfelt determination to spare Ferro even a trifling inconvenience and the mere shadow of a remote danger, such as that of entering a cage and firing at an animal which everyone says is cowed by all these months of captivity. There: she has taken him neatly by the nose and amid universal laughter has led him into the cage.

Even the most moral of moralists, unintentionally, between the lines of their fables, allow us to observe their keen delight in the cunning of the fox, at the expense of the wolf or the rabbit or the hen: and heaven only knows what the fox represents in those fables! The moral to be drawn from them is always this: that the loss and the ridicule are borne by the foolish, the timid, the simple, and that the thing to be valued above all is therefore cunning, even when the fox fails to reach the grapes and says that they are sour. A fine moral! But this is a trick that the fox is always playing on the moralists, who, do what they may, can never succeed in making him cut a sorry figure. Have you laughed at the fable of the fox and the grapes? I never did. Because no wisdom has ever seemed to me wiser than this, which teaches us to cure ourselves of every desire by despising its object.

This, you understand, I am now saying of myself, who would like to be a fox and am not. I cannot find it in me to say sour grapes to Signorina Luisetta. And that poor child, whose heart I have not been able to reach, here she is doing everything in her power to make me, in her company, lose my reason, my calm impassivity, abandon the fine wise course which I have repeatedly declared my intention of following, in short all my boasted ‘inanimate silence’. I should like to despise her, Signorina Luisetta, when I see her throwing herself away like this upon that fool; I cannot. The poor child can no longer

sleep, and comes to tell me so every morning in my room, with eyes that change in colour, now a deep blue, now a pale green, with pupils that now dilate with terror, now contract to a pair of pin-points which seem stabbed by the most acute anguish.

I say to her: “You don’t sleep? Why not?” prompted by a malicious desire, which I would like to repress but cannot, to annoy her. Her youth, the calm weather ought surely to coax her to sleep. No? Why not? I feel a strong inclination to force her to tell me that she lies awake because she is afraid that he… Indeed? And then: “No, no, sleep sound, everything is going well, going perfectly. You should see the energy with which he has set to work to interpret his part in the tiger film! And he does it really well, because as a boy he used to say that if his grandfather had allowed it, he would have gone upon the stage; and he would not have been wrong! A marvellous natural aptitude; a true thoroughbred distinction; the perfect composure of an

English gentleman following the perfidious ‘Miss’ on her travels in the East! And you ought to see the courteous submission with which he accepts advice from the professional actors, from the producers Bertini and Polacco, and how delighted he is with their praise! So there is nothing to be afraid of, Signorina. He is perfectly calm….” “How do you account for that?” “Why, in this way, perhaps, that having never done anything, lucky fellow, in his life, now that, by force of circumstances, he has set himself to do something, and the very thing that at one time he would have liked to do, he has taken a fancy to it, finds distraction in it, flatters his vanity with it.”

No! Signorina Luisetta says no, persists in repeating no, no, no; that it does not seem to her possible; that she cannot believe it; that he must be brooding over some act of violence, which he is keeping dark.

Nothing could be easier, when a suspicion of this sort has taken root, than to find a corroborating significance in every trifling action. And Signorina Luisetta finds so many! And she comes and tells me about them every morning in my room: “He is writing,” “He is frowning,” “He never looked up,” “He forgot to say good morning….”

“Yes, Signorina, and what about this; he blew his nose with his left hand this morning, instead of using his right!”

Signorina Luisetta does not laugh: she looks at me, frowning, to see whether I am serious: then goes away in a dudgeon and sends to my room Cavalena, her father, who (I can see) is doing everything in his power, poor man, to overcome in my presence the consternation which his daughter has succeeded in conveying to him in its strongest form, trying to rise to abstract considerations.

“Women!” he begins, throwing out his hands. “You, fortunately for yourself (and may it always remain so, I wish with, all my heart, Signor Gubbio!) have never encountered the Enemy upon your path. But look at me! What fools the men are who, when they hear woman called’the enemy,’ at once retort: ‘But what about your mother? Your sisters? Your daughters?’ as though to a man, who in that case is a son, a brother, a father, those were women! Women, indeed! One’s mother? You have to consider your mother in relation to your father, and your sisters or daughters in relation to their husbands; then the true woman, the enemy will emerge! Is there anything dearer to me than my poor darling child? Yet I have not the slightest hesitation in admitting, Signor Gubbio, that even she, undoubtedly, even my Sesè is capable of becoming, like all other women when face to face with man, the enemy. And there is no goodness of heart, there is no submissiveness that can restrain them, believe me! When, at a turn in the road, you meet her, the particular woman, to whom I refer, the enemy: then one of two things must happen: either you kill her, or you have to submit, as I have done. But how many men are capable of submitting as I have done? Grant me at least the meagre satisfaction of saying very few, Signor Gubbio, very few!”

I reply that I entirely agree with him.

Whereupon: “You agree?” asks Cavalena, with a surprise which he makes haste to conceal, fearing lest from his surprise I may divine his purpose. “You agree?”

And he looks me timidly in the face, as though seeking the right moment to descend, without marring our agreement, from the abstract consideration to the concrete instance. But here I quickly stop him.

“Good Lord, but why,” I ask him, “must you believe in such a desperate resolution on Signora Nestoroff’s part to be Signor Nuti’s enemy!”

“What’s that? But surely? Don’t you think so? But she is! She is the enemy!” exclaims Cavalena. “That seems to me to be unquestionable!”

“And why?” I persisted. “What seems to me unquestionable is that she has no desire to be his friend or his enemy or anything at all.”

“But that is just the point!” Cavalena interrupts me. “Surely; or do you mean that we ought to consider woman in and by herself? Always in relation to a man, Signor Gubbio! The greater enemy, in certain cases, the more indifferent she is! And in this case, indifference, really, at this stage? After all the harm that she has done him? And she doesn’t stop at that; she must make a mock of him, too. Really!”

I gaze at him for a while in silence, then with a sigh return to my original question:

“Very good. But why must you now believe that the indifference and mockery of Signora Nestoroff have provoked Signor Nuti to (what shall I say?) anger, scorn, violent plans of revenge? On what do you base your argument? He certainly shews no sign of it! He keeps perfectly calm, he is looking forward with evident pleasure to his part as an English gentleman….”

“It is not natural! It is not natural!” Cavalena protests, shrugging his shoulders. “Believe me, Signor Gubbio, it is not natural! My daughter is right. If I saw him cry with rage or grief, rave, writhe, waste away, I should say ‘amen’. You see, he is tending towards one or other alternative.”

“You mean?”

“The alternatives between which a man can choose when he is face to face with the enemy. Do you follow me? But this calm, no, it is not natural! We have seen him go mad here, for this woman, raving mad; and now…. Why, it is not natural! It is not natural!”

At this point I make a sign with my finger, which poor Cavalena does not at first understand.

“What do you mean?” he asks me.

I repeat the sign; then, in the most placid of tones:

“Go up higher, my friend, go up higher….” “Higher… what do you mean?”

“A step higher, Signor Fabrizio; rise a step above these abstract considerations, of which you began by giving me a specimen. Believe me, if you are in search of comfort, it is the only way. And it is the fashionable way, too, to-day.”

“And what is that?” asks Cavalena, bewildered.

To which I:

“Escape, Signor Fabrizio, escape; fly from the drama! It is a fine thing, and it is the fashion, too, I tell you. Let yourself e-va-po-rate in (shall we say?) lyrical expansion, above the brutal necessities of life, so ill-timed and out of place and illogical; up, a step above every reality that threatens to plant itself, in its petty crudity, before our eyes. Imitate, in short, the songbirds in cages, Signor Fabrizio, which do indeed, as they hop from perch to perch, cast their droppings here and there, but afterwards spread their wings and fly: there, you see, prose and poetry; it is the fashion. Whenever things go amiss, whenever two people, let us say, come to blows or draw their knives, up, look above you, study the weather, watch the swallows dart by, or the bats if you like, count the passing clouds; note in what phase the moon is, and if the stars are of gold or silver. You will be considered original, and will appear to enjoy a vaster understanding of life.”

Cavalena stares at me open-eyed: perhaps he thinks me mad.

Then: “Ah,” he says, “to be able to do that!”

“The easiest thing in the world, Signor Fabrizio! What does it require? As soon as a drama begins to take shape before you, as soon as things promise to assume a little consistency and are about to spring up before you solid, concrete, menacing, just liberate from within you the madman, the frenzied poet, armed with a suction pump; begin to pump out of the prose of that mean and sordid reality a little bitter poetry, and there you are!”

“But the heart?” asks Cavalena.

“What heart?”

“Good God, the heart! One would need to be without one!”

“The heart, Signor Fabrizio! Nothing of the sort. Foolishness. What do you suppose it matters to my heart if Tizio weeps or Cajo weds, if Sempronio slays Filano, and so on? I escape, I avoid the drama, I expand, look, I expand!”

What do expand more and more are the eyes of poor Cavalena. I rise to my feet and say to him in conclusion:

“In a word, to your consternation and that of your daughter, Signor Fabrizio, my answer is this: that I do not wish to hear any more; I am weary of the whole business, and should like to send you all to blazes. Signor Fabrizio, tell your daughter this: my job is to be an operator, there!”

And off I go to the Kosmograph.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (33)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

foto: jef van kempen

Esther Porcelijn

Niet nog een column over Stapel

Diederik Stapel was weer overal in het nieuws. Als hij dan eindelijk na twee dagen uit het nieuws en uit de carrousel van Pauw en Witteman is gezwiept, dan moddert zijn naam nog even door in alle columns en blogs van opiniebladen en online magazines. Best wel irritant eigenlijk.

Bert Brussen (De Jaap) schreef op dinsdag 3 december een zeer kritische en scherpe analyse van het boek van Stapel:

Hierin duidt Brussen het boek van Stapel als een symptoom van zijn nog altijd bestaande hang naar aandacht en erkenning. Voor Brussen is de kritiek en de ‘karaktermoord’ op Stapel ook een aanduiding van de angst van mensen om medeplichtig te zijn aan ditzelfde klimaat waar Stapel in floreerde. Als je iemand aanwijst als de zondebok en zijn handelen beschrijft als onmenselijk, dan zijn alle andere mensen in elk geval niet zoals hij en hoef je ook niet bang te zijn dat je zelf zo bent of zou kunnen zijn; Stapel is onmenselijk, jij niet, dus jij bent niet zoals Stapel.

De sociale psychologie als wetenschap moet er ook aan geloven in de analyse van Brussen en van de commissie Levelt: ‘Stapel kon zo handelen door gebrek aan kritiek.’

De hele wetenschap der Sociale Psychologie heeft een enorme opdonder gekregen, eventueel terecht. Maar gezien Stapel als monster is afgeschilderd, valt de rest van de sociaal psychologen onmiddellijk buiten die categorie.

Onder filosofen worden wetenschappen als sociale psychologie eigenlijk vrij snel als pseudo-wetenschap bestempeld. Een bepaalde tak van de filosofie zal tot in het einde der tijden puur empirisch onderzoek een onvolledige bron van kennis vinden, andere takken van de filosofie zullen niet zozeer tegen dit soort onderzoek zijn, maar zullen te hapklare conclusies wel altijd wantrouwen. Het is makkelijk om vanaf de zijlijn te zeggen, maar had één filosoof bij de onderzoeken van Stapel gezet, en die had de conclusies onmiddellijk bevraagd: Hoe weet je dit zeker? Zijn dit soort data niet altijd heel contingent? Weet je zeker dat je deze conclusie niet hebt getrokken omdat je dit eigenlijk in je vraagstelling al had verwacht? Kun je echt zo hard stellen dat iemand die a doet, altijd in de categorie b valt?

Grappig is dat de Stapel-affaire niet zo heel uitgebreid is besproken op het departement Filosofie, ook omdat niemand hem persoonlijk kende, en wij geen van allen college van hem hadden maar misschien ook omdat het filosofen niet verbaast.

Toen de affaire een affaire begon te worden besefte ik pas echt hoeveel impact dit had op de universiteit toen ik hierover vragen kreeg van vrienden uit andere steden. Van een afstand lijkt zoiets wat te zeggen over de gehele universiteit, terwijl een vriend van de Uvt, die psychologie studeert, ook nooit college van Stapel had gevolgd en eigenlijk niet precies wist wie het was.

Imagoschade. Er is alleen al sprake van imagoschade omdat het zovaak genoemd wordt. Er is sprake van imagoschade dus is er sprake van imagoschade.

Een paar dagen geleden besprak ik de nieuwtjes over Stapel met een vriend van mij uit Rotterdam. Ik was heftig aan het vertellen over onderzoekers die hun graad dreigen te verliezen, over onderzoekers die ineens tien onderzoeken van hun publicatielijst moeten schrappen en zo ongeveer opnieuw moeten beginnen. Ik stelde mij voor dat dit hun levenswerk is en dat dit nu een lege huls blijkt te zijn.

De vriend antwoordde met: “Maar dat is toch niet erg? Niet echt erg.”

Dus ik vertelde nog heftiger over imagoschade en onderzoeksgeld, over geloofwaardigheid en over de wetenschap als autoriteit.

De vriend vond het nog altijd niet echt iets wat ‘erg’ genoemd kan worden, hij zei dat als iets te maken heeft met geld dit nog niet meteen erg is.

Ik begreep wel wat hij bedoelde, het is niet erg zoals dode kinderen erg zijn, niet erg zoals voedselbanken zonder voedsel. Dat soort dingen zijn veel erger. Als ik dat niet al zou vinden dan zou ik het wel moeten vinden, anders ben ik een monster en dus een soort Stapel.

Het spreekt voor zich dat dit een ander soort erg is. Maar het is erg. Dat moet wel even benoemd worden natuurlijk.

Imagoschade om de imagoschade.

Erg om de erg.

Ik erken dit automatisch door deze tekst te schrijven, als ik het niet erg vond, of erg was gaan vinden of er niets van zou vinden dan zou ik dit niet schrijven.

Misschien toch goed dat de vriend van mij die vraag stelde: is het echt erg?

Het is niet alleen goed door het antwoord dat je zou kunnen geven, maar goed omwille van de vraag zelf. Anders zou ik toch zomaar iets vinden omdat het gevonden dient te worden. Dat soort vragen hadden aan Stapel gesteld moeten worden.

En nu zal ik niets meer schrijven over deze affaire, heus beloofd!

Ik zal er niets meer over schrijven omdat ik er verder niets aan toe te voegen heb. Ik hoop dat er beter onderzoek gedaan wordt en dat mensen die er nog wel over schrijven dit niet doen om zichzelf buiten Stapel te plaatsen als een zichzelf schoonwassende vingerwijzer. Klaar nu. Echt. Ja echt.

Stapel.

Esther Porcelijn (27) studeert filosofie (bachelor) aan de Universiteit van Tilburg en is stadsdichter.

Eerder gepubliceerd in UNIVERS 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature