Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Hans Leybold

(1892-1914)

Ende

Die Wellen meiner bunten Räusche sind verdampft.

Breit schlagen, schwer und müd

die Ströme meines Lebens über Bänke

von Sand.

Mir schmerzen die Gelenke.

In mein Gehirn

hat eine maßlos große Faust sich eingekrampft.

Hans Leybold poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Leybold, Hans

Bert

BEVERS

Sedan, april 1940

Aan een grens een stadje dat

sluimert tegen verre heuvels.

Geen vijand valt er te bekennen.

Een officier te paard trekt

ter inspectie langs de wegen,

in handen los de teugels.

Onaangekondigd meldt de tijd

zich aan de poorten die

in rust gedompeld zijn.

Wat valt er hier dan meer te doen

dan in alledaagse sleur

te worden overrompeld?

Bert Bevers

(Verschenen in De Tweede Ronde, Amsterdam, 8ste jaargang, nummer 4)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Wilfred Owen

(1893 – 1918)

A Terre

(being the philosophy of many soldiers)

Sit on the bed. I’m blind, and three parts shell.

Be careful; can’t shake hands now; never shall.

Both arms have mutinied against me,-brutes.

My fingers fidget like ten idle brats.

I tried to peg out soldierly,-no use!

One dies of war like any old disease.

This bandage feels like pennies on my eyes.

I have my medals?-Discs to make eyes close.

My glorious ribbons?-Ripped from my own back

In scarlet shreds. (That’s for your poetry book.)

A short life and a merry one, my buck!

We used to say we’d hate to live dead-old,-

Yet now…I’d willingly be puffy, bald,

And patriotic. Buffers catch from boys

At least the jokes hurled at them. I suppose

Little I’d ever teach a son, but hitting,

Shooting, war, hunting, all the arts of hurting.

Well, that’s what I learnt,-that, and making money.

Your fifty years ahead seem none too many?

Tell me how long I’ve got? God! For one year

To help myself to nothing more than air!

One Spring! Is one too good to spare, too long?

Spring wind would work its own way to my lung,

And grow me legs as quick as lilac-shoots.

My servant’s lamed, but listen how he shouts!

When I’m lugged out, he’ll still be good for that.

Here in this mummy-case, you know, I’ve thought

How well I might have swept his floors for ever.

I’d ask no nights off when the bustle’s over,

Enjoying so the dirt. Who’s prejudiced

Against a grimed hand when his own’s quite dust,

Less live than specks that in the sun-shafts turn,

Less warm than dust that mixes with arms’ tan?

I’d love to be a sweep, now, black as Town,

Yes, or a muckman. Must I be his load?

O Life, Life, let me breathe,-a dug-out rat!

Not worse than ours the lives rats lead-

Nosing along at night down some safe rut,

They find a shell-proof home before they rot.

Dead men may envy living mites in cheese,

Or good germs even. Microbes have their joys,

And subdivide, and never come to death.

Certainly flowers have the easiest time on earth.

‘I shall be one with nature, herb, and stone’

Shelley would tell me. Shelley would be stunned:

The dullest Tommy hugs that fancy now.

‘Pushing up daisies’ is their creed, you know.

To grain, then, go my fat, to buds my sap,

For all the usefulness there is in soap.

D’you think the Boche will ever stew man-soup?

Some day, no doubt, if…Friend, be very sure

I shall be better off with plants that share

More peaceably the meadow and the shower.

Soft rains will touch me,-as they could touch once,

And nothing but the sun shall make me ware.

Your guns may crash around me. I’ll not hear;

Or, if I wince, I shall not know I wince.

Don’t take my soul’s poor comfort for your jest.

Soldiers may grow a soul when turned to fronds,

But here’s the thing’s best left at home with friends.

My soul’s a little grief, grappling your chest,

To climb your throat on sobs; easily chased

On other sighs and wiped by fresher winds.

Carry my crying spirit till it’s weaned

To do without what blood remained these wounds.

Wilfred Owen poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive O-P, Owen, Wilfred

Hans Leybold

(1892-1914)

Der Tod des Menschen

Er hatte auf einmal kein Gesicht mehr.

Wo das sonst war, war nun eine weiße Fläche.

Seine Augen waren hinter die Schädelwand gerutscht.

Die Hände lagen unter seinen Füßen: man wusste

nicht, wie sie dorthin gekommen waren.

Seine Stimme war unter den Tisch gefallen; hatte

dort gescheppert, wie ein Tonteller; und war

dann plötzlich zerbrochen, mit einem letzten Klang.

Eine unvermutete Zigarre rauchte sich selbst auf.

Blies blaue Dünste.

Die krochen schweigsam in die getilgten Nasenlöcher des Menschen.

Da bissen sie sich fest; kratzten unnervige Wände. – –

Des Menschen Seele aber stolperte schon in paradiesischen Feldern.

Keine Windmühle störte seine nichterhoffte Aussicht.

Der Blick war weit und groß und grün.

Insekten tanzten golden.

Äcker brannten.

Hans Leybold poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Expressionism, Hans Leybold, Leybold, Hans

Hans Leybold

(1892-1914)

Traum der Sehnsucht

Wie oft hab ich meine Arme ausgebreitet

In der Nacht

Und hab gelegen

Und hab gewacht

Und hab gewartet auf dich …

Du musstest einmal kommen,

Und du kamst!

Du musstest kommen

Und du nahmst

All dies einsamgraue, öde Elend fort …

Du kamst wie ein Rosenhauch

In den Raum

Und knietest an meinem Bette –

Mir war’s wie ein Traum …

Und meine Arme schlossen sich

Sanft um deine gebeugte Gestalt.

Ich küsste Stirn dir und Haar,

Wieder und wieder … und mir war,

Als entzöge dich mir eine sanfte Gewalt …

Wo bliebst du … wo …?

Hart und roh

Schlägt mein Kopf an den Boden –!

Hans Leybold poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Expressionism, Leybold, Hans

Hans Leybold

(1892-1914)

O über allen Wolkenfahnen ...

O über allen Wolkenfahnen,

die windgetrieben sich in Bläue krallen,

stehen unverrückbar Sonnen, welche niemals fallen.

wir schwingen uns bewegt in ihre Bahnen,

sind selber Nebel und bestrahlte Dämpfe.

Verdrängen wir die nächt’gen Schatten

der Erdendinge! Lassen alle nimmersatten

Begierden. Gelöst sind alle Krämpfe,

die hart die Glieder engten.

Wir werden Äther, Luft und Wellen.

Oh, aus unsern Leibern strömen Quellen,

spritzend in das ungewohnte Licht! Wir schenkten

uns dem All! Es hat uns königlich empfangen.

Mit Sturmtrompeten und mit Regenwehen.

Wie unsre Füße über Sonnenbrücken gehen!

In unsrer Hände Kelch hat sich ein Tropfen Gold gefangen.

Hans Leybold poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Hans Leybold, Leybold, Hans

Hans Leybold

(1892-1914)

Auch ein Nekrolog

für Christian Morgenstern

O Christian, wir glätten weinend unsre Bügelfalten:

auf Feuerleitern krochen wir mit dir in rhythmische Gerüste.

Mit dem Zement der Ironie ausfülltest du die Spalten

vermorschter Traditionen Mauer. O metaphysisches Gelüste.

O Huhn und Bahnhofshalle! Weit entfernte Latten!

Ihr Wiesel, Kiesel, mitten mang det Bachjeriesel!

Palmström, du ohngeschneuzter, den sie kastrieret hatten!

Genosse Korf, du nie banaler Wennschon – Stiesel!

(Verzeiht den Kitschton. Mich übermannte hier die Rührung.

Verzeih besonders du, Kollege Untermstriche:

schon hab ich in der harten Hand der Verse Führung

wieder; und komme mir auf meine Schliche.) –

Nun quäkt der Turmhahn geil auf Staackmanns Miste

sein Kikriki, und ist bald Ernst, bald Otto.

Verleger reißen sich die Haare aus, als ob das müßte,

und spielen mit der Perioden-Presse trotzdem Lotto.

O Christian: wie später Gotik wandgeklatschter Freske

(im spitzen Reigen härmender sebastianischer Figuren):

du paßtest nicht in unsren Krämerkram, du fleischgewordene Groteske;

nicht schmiegte sich dein edler Vollbart in die Schöße unsrer Huren!

Das Literatenleben, o du mein Christian, ist doch nicht besser

als das ärarische. (Sie dichten zur Musik von Walter Kollo!)

Wir tanzen zwischen Film und Feuilleton auf scharfem Messer . . .

Freu dich! Sei tot! Grüß mir, im Glanz geölter Locken, den Apollo!

Hans Leybold poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Hans Leybold, Leybold, Hans

Hans Leybold

(1892-1914)

Konfusion – Ein Film

Plötzlich sprangen in den Straßen Gräber auf wie Erbsenschoten,

und jämmerliche Wesen wälzten sich heraus, die drohten

mit ihren blassgebleichten Knochen ihren Ururenkeln:

Die stoben fort und auseinander, als brennte es in ihren Schenkeln,

Pest oder Cholera im Bauch oder Jüngster Tag am Ende

(man muss doch sehn, ob man Rettung fände,

man hat sein kleines Leben lieb; die Hände,

die sich über alles strecken – –

wer weiß, ob man schlauer ist, versucht, sich zu verstecken).

Sie hopsen, springen ängstlich über Straßenbahngeleise

sie tanzen durcheinander: jeder in seiner Weise,

der eine verkriecht sich im Lokus, um sich zu retten,

der verwälzt sich tief in seine Betten,

viele fallen über die Geländer hoher Brücken,

fallen in hochgeschwollene Ströme, müssen in großen Schlücken

gelbes Wasser saufen, andere aber drücken

voll Furcht vor Unbekanntem sich an ihre Weiber.

Auf einmal greift eine unmäßig große Hand vom Himmel,

schiebt sich langsam durch chaotische Gewimmel,

plättet die Straßen als wären sie Wäsche,

greift aus dem Gewühl sich ein paar besonders fesche

Kokotten und Kavaliere, ein paar dicke Kommerzienräte,

stört in den diversen Salons die Abschiedsfete,

stürzt Börse und Kirche und Rathaus um, als mähte

sie Gras … hebt sich, verschwindet … nichts ist passiert.

Ein Gentleman sieht nach, außerordentlich blasiert.

Hans Leybold poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Hans Leybold, Leybold, Hans

Alfred Lichtenstein

(1889-1914)

Der Athlet

Einer ging in zerrissenen Hausschuhen

Hin und her durch das kleine Zimmer,

Das er bewohnte.

Er sann über die Geschehnisse,

Von denen in dem Abendblatt berichtet war.

Und gähnte traurig, wie nur jemand gähnt,

Der viel und Seltsames gelesen hat –

Und der Gedanke überkam ihn plötzlich,

Wie wohl den Furchtsamen die Gänsehaut

Und wie das Aufstoßen den Übersättigten,

Wie Mutterwehen:

Das große Gähnen sei vielleicht ein Zeichen,

Ein Wink des Schicksals, sich zur Ruh zu legen.

Und der Gedanke ließ ihn nicht mehr los.

Und also fing er an, sich zu entkleiden …

Als er ganz nackt war, hantelte er etwas.

Alfred Lichtenstein poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Expressionism, Lichtenstein, Alfred

Hans Leybold

(1892-1914)

Auf einer Feldpostkarte

Zerflossen alles

in wirren Schaum,

mein Hirn ein weiter

luftleerer Raum.

Von außen schlagen

die Hämmer drauf:

mein Schädel ist

ein Kirchturmknauf.

Hans Leybold poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Hans Leybold, Leybold, Hans

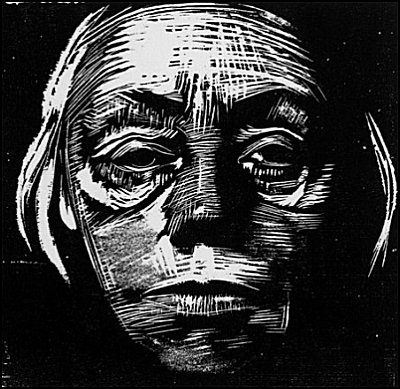

K ä t h e K o l l w i t z

D i e T o t e n m a h n e n u n s

( I I ) B i l d e r

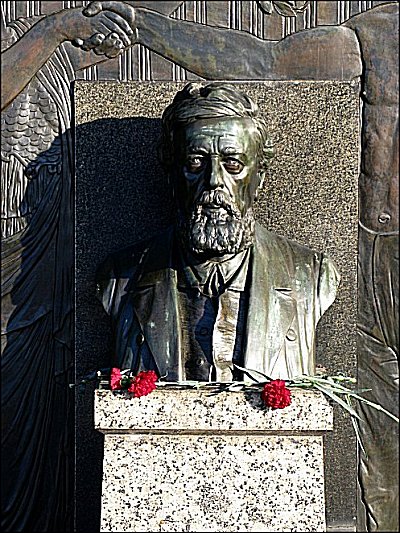

Denkmal Karl Liebknecht

Denkmal Ernst Thalmann

.jpg)

Käthe Kollwitz

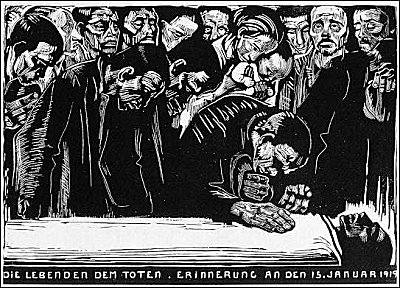

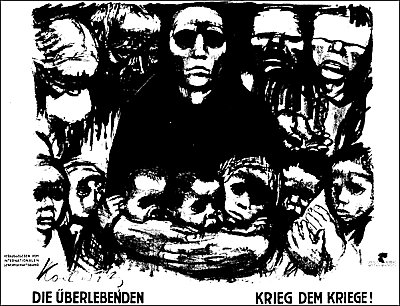

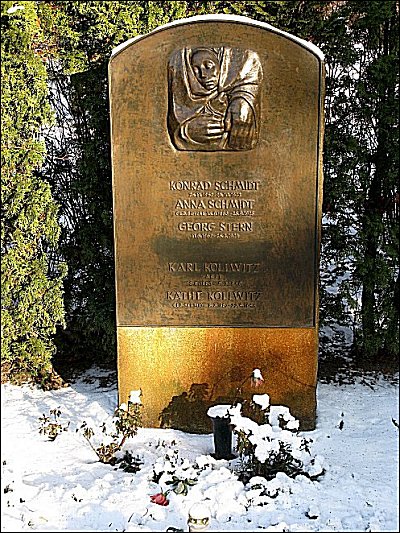

Die Toten mahnen uns (II) Bilder

Photos: Anton K. Berlin

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Anton K. Photos & Observations, Käthe Kollwitz

.jpg)

K ä t h e K o l l w i t z

Die Toten Mahnen uns

Berlin

The street names still reflect old DDR times, before the demolishment of the wall in 1989. The Karl-Liebknecht-Straße runs alongside the Alexanderplatz and connects Prenzlauer Berg to the Museuminsel and Unter den Linden. At the Rosa-Luxembourg-Platz, a few hundred meters to the north, a monument to Herbert Baum and a memorial plaque to Ernst Thälmann commemorate the resistance of the communists against fascism and against the wars that overshadowed life in Europe during the first half of the 20th century. The rise of a working class who lived in miserable conditions dominated social discussions in the early 1900’s. In 1914 a complex combination of imperialism, militarism and strong nationalistic feelings led to the First World War which eventually involved 75 percent of the world’s population and took the lives of 20 million soldiers and civilians. After the war the political situation in Germany remained unstable. The Treaty of Versailles declared Germany responsible for the war, it redefined its territory and Germany was forced to pay enormous war reparations. This treaty caused great bitterness in Germany and was a source of inspiration for both left and right extremism. It eventually led to the rise of fascism and the Second World War. Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg, founders of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschland (KPD), were killed in 1919 by Freikorpsen, right extremist remainders of the German army. Herbert Baum and his resistance group were killed by the Gestapo in 1942 and Ernst Thälmann, Hitlers political opponent during the elections of 1932, was executed in Buchenwald in August 1944, on direct orders from Hitler.

Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Schmidt was born in Königsberg in 1867 in a family of social democrats that were sensitive to the changes that were taking place in society. Her talent for art was recognised and stimulated by her father. She received lessons in drawing in a private art school in Berlin. Under the influence of her teacher Stauffer-Bern and the work of Max Klinger she decided to focus on black and white drawing, etching and lithography. She married Karl Kollwitz, a friend of the family, in 1891. Karl had decided to dedicate his live to the poor working class and started a doctor’s practice in Prenzlauer Berg in a street that is now called the Käthe-Kollwitz-Straße. They had 2 sons, Hans and Peter. Käthe was deeply moved by the social misery she was confronted with in her husbands practice and the life of the working class became a dominant theme in her work. It was Gerhard Hauptman’s play ‘die Weber’ that inspired her to her first successful series of etchings called ‘Ein Weberaufstand’. Another successful series was ‘Bauernkrieg” for which she received the prestigious ‘Villa Romana’ price. At the age of 50 Käthe had become famous throughout Germany and to the occasion of her birthday, exhibitions of her work were held in Berlin, Bremen and Königsberg.

In October 1914 her son Peter was killed in the trenches of Flanders. To his memory Käthe designed a monument which took her almost 18 years to complete. In Diksmuide-Vladslo, in a landscape covered by hundreds of war cemeteries, her ‘Grieving Parents’ impressively expresses the poignant grief and helplessness of parents who have lost a child. The death of her son had a great impact on her work and war and death became the dominant themes. When Karl Liebknecht was killed in 1919 his family asked Käthe to make a drawing to his memory. In a charcoal drawing she depicts the worker’s farewell to Liebknecht. A final version in woodcut was made 2 years later. Sieben Holzschitte zur Krieg were made in 1920/1923 and her famous poster Nie Wieder Krieg, a consignment by the International Labours Union, in 1924. She was not the only artist that stood up against war but while the artistic protests of for instance George Grosz, Otto Dix or Frans Masereel were primarily aimed at the horrors of the battlefield or the political climate, Käthe Kollwitz’s concern was with the human suffering of those who were left behind.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, she and her husband signed an urgent appeal to unite the working class and to the formation of a front against Hitler. The SPD and KPD were forbidden by the Nazis and Käthe was removed from her position at the Berlin Art Academy where she was heading the Masterclass of Graphics. Exhibitions of her work were forbidden. Karl was also temporarily disallowed to exercise his practice and their financial situation became precarious until his ban was relieved due to a shortage of skilled physicians. Karl Kollwitz, after a life dedicated to the health of the poor, died in July 1940.

After Karl’s death Käthe suffered from depression and her physical condition was rapidly declining. The house in Berlin where she and Karl had been living since 1891 was bombed in 1943 and Käthe was evacuated to Nordhausen and later to Moritzburg. A few days before the end of the Second World War, in April 1945, Käthe Kollwitz died. She was buried in the family grave in Berlin-Friedrichsfelde at the same cemetery where a memorial monument pays tribute to the socialist heroes Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxembourg and Ernst Thälmann.

A mission

Käthe’s importance as an artist cannot be overvalued. Her authentic, expressive depictions of human misery, resulting from the exploitation of human labour, from fascism and war, are timeless, genuine and moving. She was not a politician but an artist with a vocation who found a way to make art that goes straight to the heart.

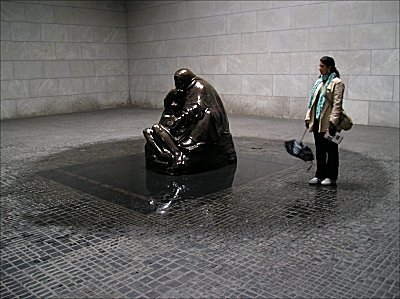

When you are in Berlin be sure to visit ‘Die Neue Wache’, a building designed by Christian Schinkel, which since the 1960-s is a monument against war and fascism. In the centre of the building, right beneath a circular opening in the ceiling, Käthe Kollwitz’s sculpture Mother and Child is an arresting plea for vigilance against mentalities and attitudes that may again lead to fascism and war.

References:

Ilse Kleberger: Kathe Kollwitz, Eine Biographie

Venues

Neue Wache – Unter den Linden near the Museuminsel

Kathe Kollwitzmuseum Berlin – Fasanenstrasse 24

Käthe Kollwitz: Die Toten mahnen uns – part I

Photos & text: Anton K. Berlin

![]()

Find also on fleursdumal.nl magazine:

Nie Wieder: Wache gegen Faschismus

and

Historia Belgica: Alles voor Vlaanderen

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

to be continued

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Anton K. Photos & Observations, Fascism, Käthe Kollwitz, Sculpture

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature