Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

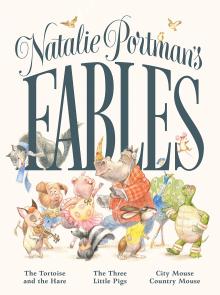

Academy Award-winning actress, director, producer, and activist Natalie Portman retells three classic fables and imbues them with wit and wisdom.

From realizing that there is no “right” way to live to respecting our planet and learning what really makes someone a winner, the messages at the heart of Natalie Portman’s Fables are modern takes on timeless life lessons.

From realizing that there is no “right” way to live to respecting our planet and learning what really makes someone a winner, the messages at the heart of Natalie Portman’s Fables are modern takes on timeless life lessons.

Told with a playful, kid-friendly voice and perfectly paired with Janna Mattia’s charming artwork, Portman’s insightful retellings of The Tortoise and the Hare, The Three Little Pigs, and Country Mouse and City Mouse are ideal for reading aloud and are sure to become beloved additions to family libraries.

Natalie Portman is an Academy Award-winning actress, director, producer, and activist whose credits include Leon: The Professional, Cold Mountain, Closer, V for Vendetta, the Star Wars franchise prequels, A Tale of Love and Darkness, Jackie, and Thor: Love and Thunder. Born in Jerusalem, Israel, she is a graduate of Harvard University, and now lives with her family in Los Angeles. Natalie Portman’s Fables is her debut picture book.

Janna Mattia was born and raised in San Diego. She received a degree in Illustration for Entertainment from Laguna College of Art and Design, and now works on concept and character art for film, illustration for licensing, and private commissions. Natalie Portman’s Fables is her picture book debut.

Natalie Portman’s Fables

Natalie Portman (Author)

Janna Mattia (Illustrator)

Age Range: 4 – 6 years

Hardcover: 64 pages

Publisher: Feiwel & Friends (October 20, 2020)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1250246865

ISBN-13: 978-1250246868

$17.99

# new books

Natalie Portman’s Fables

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive O-P, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Gevatter Tod

Es lebte einmal ein sehr armer Mann, hieß Klaus, dem hatte Gott eine Fülle Reichtum beschert, der ihm große Sorge machte, nämlich zwölf Kinder, und über ein kleines so kam noch ein Kleines, das war das dreizehnte Kind. Da wußte der arme Mann seiner Sorge keinen Rat, wo er doch einen Paten hernehmen sollte, denn seine ganze Sipp- und Magschaft hatte ihm schon Kinder aus der Taufe gehoben, und er durfte nicht hoffen, noch unter seinen Freunden eine mitleidige Seele zu finden, die ihm sein jüngstgebornes Kindlein hebe. Gedachte also an den ersten besten wildfremden Menschen sich zu wenden, zumal manche seiner Bekannten ihn in ähnlichen Fällen schon mit vieler Hartherzigkeit abschläglich beschieden hatten.

Der arme Kindesvater ging also auf die Landstraße hinaus, willens, dem ersten ihm Begegnenden die Patenstelle seines Kindleins anzutragen. Und siehe, ihm begegnete bald ein gar freundlicher Mann, stattlichen Aussehens, wohlgestaltet, nicht alt nicht jung, mild und gütig von Angesicht, und da kam es dem Armen vor, als neigten sich vor jenem Manne die Bäume und Blümlein und alle Gras- und Getreidehalme. Da dünkte dem Klaus, das müsse der liebe Gott sein, nahm seine schlechte Mütze ab, faltete die Hände und betete ein Vater Unser. Und es war auch der liebe Gott, der wußte, was Klaus wollte, ehe er noch bat, und sprach: »Du suchst einen Paten für dein Kindlein! Wohlan, ich will es dir heben, ich, der liebe Gott!«

»Du bist allzugütig, lieber Gott!« antwortete Klaus verzagt. »Aber ich danke dir; du gibst denen, welche haben, einem Güter, dem andern Kinder, so fehlt es oft beiden am Besten, und der Reiche schwelgt, der Arme hungert!« Auf diese Rede wandte sich der Herr und ward nicht mehr gesehen. Klaus ging weiter, und wie er eine Strecke gegangen war, kam ein Kerl auf ihn zu, der sah nicht nur aus, wie der Teufel, sondern war’s auch, und fragte Klaus, wen er suche? – Er suche einen Paten für sein Kindlein. – »Ei da nimm mich, ich mach es reich!« – »Wer bist du!« fragte Klaus. »Ich bin der Teufel« – »Das wär der Teufel!« rief Klaus, und maß den Mann vom Horn bis zum Pferdefuß. Dann sagte er: »Mit Verlaub, geh heim zu dir und zu deiner Großmutter; dich mag ich nicht zum Gevatter, du bist der Allerböseste! Gott sei bei uns!«

»Du bist allzugütig, lieber Gott!« antwortete Klaus verzagt. »Aber ich danke dir; du gibst denen, welche haben, einem Güter, dem andern Kinder, so fehlt es oft beiden am Besten, und der Reiche schwelgt, der Arme hungert!« Auf diese Rede wandte sich der Herr und ward nicht mehr gesehen. Klaus ging weiter, und wie er eine Strecke gegangen war, kam ein Kerl auf ihn zu, der sah nicht nur aus, wie der Teufel, sondern war’s auch, und fragte Klaus, wen er suche? – Er suche einen Paten für sein Kindlein. – »Ei da nimm mich, ich mach es reich!« – »Wer bist du!« fragte Klaus. »Ich bin der Teufel« – »Das wär der Teufel!« rief Klaus, und maß den Mann vom Horn bis zum Pferdefuß. Dann sagte er: »Mit Verlaub, geh heim zu dir und zu deiner Großmutter; dich mag ich nicht zum Gevatter, du bist der Allerböseste! Gott sei bei uns!«

Da drehte sich der Teufel herum, zeigte dem Klaus eine abscheuliche Fratze, füllte die Luft mit Schwefelgestank und fuhr von dannen. Hierauf begegnete dem Kindesvater abermals ein Mann, der war spindeldürr, wie eine Hopfenstange, so dürr, daß er klapperte; der fragte auch: »Wen suchst du?« und bot sich zum Paten des Kindes an. »Wer bist du?« fragte Klaus. »Ich bin der Tod!« sprach jener mit ganz heiserer Summe. – Da war der Klaus zum Tod erschrocken, doch faßte er sich Mut, dachte: bei dem wär mein dreizehntes Söhnlein am besten aufgehoben, und sprach: »du bist der Rechte! Arm oder reich, du machst es gleich. Topp! Du sollst mein Gevattersmann sein! Stell dich nur ein zu rechter Zeit, am Sonntag soll die Taufe sein.«

Und am Sonntag kam richtig der Tod, und ward ein ordentlicher Dot, das ist Taufpat des Kleinen, und der Junge wuchs und gedieh ganz fröhlich. Als er nun zu den Jahren gekommen war, wo der Mensch etwas erlernen muß, daß er künftighin sein Brot erwerbe, kam zu der Zeit der Pate und hieß ihn mit sich gehen in einen finsteren Wald. Da standen allerlei Kräuter, und der Tod sprach: »Jetzt, mein Pat, sollt du dein Patengeschenk von mir empfahen. Du sollt ein Doktor über alle Doktoren werden durch das rechte wahre Heilkraut, das ich dir jetzt in die Hand gebe. Doch merke, was ich dir sage. Wenn man dich zu einem Kranken beruft, so wirst du meine Gestalt jedesmal erblicken.

Stehe ich zu Häupten des Kranken, so darfst du versichern, daß du ihn gesund machen wollest, und ihn von dem Kraute eingeben; wenn er aber Erde kauen muß, so stehe ich zu des Kranken Füßen; dann sage nur: Hier kann kein Arzt der Welt helfen und auch ich nicht. Und brauche ja nicht das Heilkraut gegen meinen mächtigen Willen, so würde es dir übel ergehen!«

Damit ging der Tod von hinnen und der junge Mensch auf die Wanderung und es dauerte gar nicht lange, so ging der Ruf vor ihm her und der Ruhm, dieser sei der größte Arzt auf Erden, denn er sahe es gleich den Kranken an, ob sie leben oder sterben würden. Und so war es auch. Wenn dieser Arzt den Tod zu des Kranken Füßen erblickte, so seufzte er, und sprach ein Gebet für die Seele des Abscheidenden; erblickte er aber des Todes Gestalt zu Häupten, so gab er ihm einige Tropfen, die er aus dem Heilkraut preßte, und die Kranken genasen. Da mehrte sich sein Ruhm von Tage zu Tage.

Damit ging der Tod von hinnen und der junge Mensch auf die Wanderung und es dauerte gar nicht lange, so ging der Ruf vor ihm her und der Ruhm, dieser sei der größte Arzt auf Erden, denn er sahe es gleich den Kranken an, ob sie leben oder sterben würden. Und so war es auch. Wenn dieser Arzt den Tod zu des Kranken Füßen erblickte, so seufzte er, und sprach ein Gebet für die Seele des Abscheidenden; erblickte er aber des Todes Gestalt zu Häupten, so gab er ihm einige Tropfen, die er aus dem Heilkraut preßte, und die Kranken genasen. Da mehrte sich sein Ruhm von Tage zu Tage.

Nun geschah es, daß der Wunderarzt in ein Land kam, dessen König schwer erkrankt darnieder lag, und die Hofärzte gaben keine Hoffnung mehr seines Aufkommens. Weil aber die Könige am wenigsten gern sterben, so hoffte der alte König noch ein Wunder zu erleben, nämlich daß der Wunderdoktor ihn gesund mache, ließ diesen berufen und versprach ihm den höchsten Lohn. Der König hatte aber eine Tochter, die war so schön und so gut, wie ein Engel.

Als der Arzt in das Gemach des Königs kam, sah er zwei Gestalten an dessen Lager stehen, zu Häupten die schöne weinende Königstochter, und zu Füßen den kalten Tod. Und die Königstochter flehte ihn so rührend an, den geliebten Vater zu retten, aber die Gestalt des finstern Paten wich und wankte nicht. Da sann der Doktor auf eine List. Er ließ von raschen Dienern das Bette des Königs schnell umdrehen, und gab ihm geschwind einen Tropfen vom Heilkraut, also daß der Tod betrogen war, und der König gerettet. Der Tod wich erzürnt von hinnen, erhob aber drohend den langen knöchernen Zeigefinger gegen seinen Paten.

Dieser war in Liebe entbrannt gegen die reizende Königstochter, und sie schenkte ihm ihr Herz aus inniger Dankbarkeit. Aber bald darauf erkrankte sie schwer und heftig, und der König, der sie über alles liebte, ließ bekannt machen, welcher Arzt sie gesund mache, der solle ihr Gemahl und hernach König werden. Da flammte eine hohe Hoffnung durch des Jünglings Herz, und er eilte zu der Kranken – aber zu ihren Füßen stand der Tod. Vergebens warf der Arzt seinem Paten flehende Blicke zu, daß er seine Stelle verändern und ein wenig weiter hinauf, wo möglich bis zu Häupten der Kranken treten möge. Der Tod wich nicht von der Stelle, und die Kranke schien im Verscheiden, doch sah sie den Jüngling um ihr Leben flehend an. Da übte des Todes Pate noch einmal seine List, ließ das Lager der Königstochter schnell umdrehen, und gab ihr geschwind einige Tropfen vom Heilkraut, so daß sie wieder auflebte, und den Geliebten dankbar anlächelte. Aber der Tod warf seinen tödlichen Haß auf den Jüngling, faßte ihn an mit eiserner eiskalter Hand und führte ihn von dannen, in eine weite unterirdische Höhle. In der Höhle da brannten viele tausend Kerzen, große und halbgroße und kleine und ganz kleine; viele verloschen und andere entzündeten sich, und der Tod sprach zu seinem Paten: »Siehe, hier brennt eines jeden Menschen Lebenslicht; die großen sind den Kindern, die halbgroßen sind den Leuten, die in den besten Jahren stehen, die kleinen den Alten und Greisen, aber auch Kinder und Junge haben oft nur ein kleines bald verlöschendes Lebenslicht.«

»Zeige mir doch das meine!« bat der Arzt den Tod, da zeigte dieser auf ein ganz kleines Stümpchen, das bald zu erlöschen drohte. »Ach liebster Pate!« bat der Jüngling: »wolle mir es doch erneuen, damit ich meine schöne Braut, die Königstochter, freien, ihr Gemahl und König werden kann!« – »Das geht nicht« – versetzte kalt der Tod. »Erst muß eins ganz ausbrennen, ehe ein neues auf- und angesteckt wird.« –

»So setze doch gleich das alte auf ein neues!« sprach der Arzt – und der Tod sprach: »Ich will so tun!« Nahm ein langes Licht, tat als wollte er es aufstecken, versah es aber absichtlich und stieß das kleine um, daß es erlosch. In demselben Augenblick sank der Arzt um und war tot.

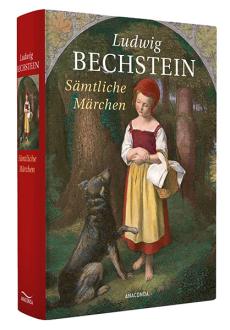

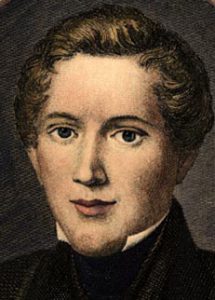

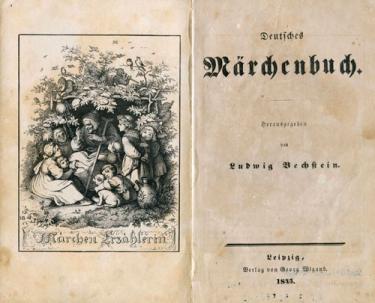

Ludwig Bechstein

(1801 – 1860)

Gevatter Tod

Sämtliche Märchen

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bechstein, Bechstein, Ludwig, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

The Little Vagabond

Dear mother, dear mother, the Church is cold;

But the Alehouse is healthy, and pleasant, and warm.

Besides, I can tell where I am used well;

The poor parsons with wind like a blown bladder swell.

But, if at the Church they would give us some ale,

And a pleasant fire our souls to regale,

We’d sing and we’d pray all the livelong day,

Nor ever once wish from the Church to stray.

Then the Parson might preach, and drink, and sing,

And we’d be as happy as birds in the spring;

And modest Dame Lurch, who is always at church,

Would not have bandy children, nor fasting, nor birch.

And God, like a father, rejoicing to see

His children as pleasant and happy as he,

Would have no more quarrel with the Devil or the barrel,

But kiss him, and give him both drink and apparel.

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

The Little Vagabond

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

The Grey Monk

“I die, I die!” the Mother said,

“My children die for lack of bread.

What more has the merciless Tyrant said?”

The Monk sat down on the stony bed.

The blood red ran from the Grey Monk’s side,

His hands and feet were wounded wide,

His body bent, his arms and knees

Like to the roots of ancient trees.

His eye was dry; no tear could flow:

A hollow groan first spoke his woe.

He trembled and shudder’d upon the bed;

At length with a feeble cry he said:

“When God commanded this hand to write

In the studious hours of deep midnight,

He told me the writing I wrote should prove

The bane of all that on Earth I lov’d.

My Brother starv’d between two walls,

His Children’s cry my soul appalls;

I mock’d at the rack and griding chain,

My bent body mocks their torturing pain.

Thy father drew his sword in the North,

With his thousands strong he marched forth;

Thy Brother has arm’d himself in steel

To avenge the wrongs thy Children feel.

But vain the Sword and vain the Bow,

They never can work War’s overthrow.

The Hermit’s prayer and the Widow’s tear

Alone can free the World from fear.

For a Tear is an intellectual thing,

And a Sigh is the sword of an Angel King,

And the bitter groan of the Martyr’s woe

Is an arrow from the Almighty’s bow.

The hand of Vengeance found the bed

To which the Purple Tyrant fled;

The iron hand crush’d the Tyrant’s head

And became a Tyrant in his stead.”

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

The Grey Monk

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Der Kranke

Zitternd auf der Berge Säume

Fällt der Sonne letzter Strahl,

Eingewiegt in düstre Träume

Blickt der Kranke in das Tal,

Sieht der Wolken schnelles Jagen

Durch das trübe Dämmerlicht —

Ach, des Busens stille Klagen

Tragen ihn zur Heimat nicht!

Und mit glänzendem Gefieder

Zog die Schwalbe durch die Luft,

Nach der Heimat zog sie wieder,

Wo ein milder Himmel ruft;

Und er hört ihr fröhlich Singen,

Sehnsucht füllt des Armen Blick,

Ach, er sah sie auf sich schwingen,

Und sein Kummer bleibt zurück.

Schöner Fluß mit blauem Spiegel,

Hörst du seine Klagen nicht?

Sag’ es seiner Heimat Hügel,

Daß des Kranken Busen bricht.

Aber kalt rauscht er vom Strande

Und entrollt ins stille Tal,

Schweiget in der Heimat Lande

Von des Kranken stiller Qual.

Und der Arme stützt die Hände

An das müde, trübe Haupt;

Eins ist noch, wohin sich wende

Der, dem aller Trost geraubt;

Schlägt das blaue Auge wieder

Mutig auf zum Horizont,

Immer stieg ja Trost hernieder

Dorther, wo die Liebe wohnt.

Und es netzt die blassen Wangen

Heil’ger Sehnsucht stiller Quell,

Und es schweigt das Erdverlangen,

Und das Auge wird ihm hell:

Nach der ew’gen Heimat Lande

Strebt sein Sehnen kühn hinauf,

Sehnsucht sprengt der Erde Bande,

Psyche schwingt zum Licht sich auf.

Wilhelm Hauff

(1802 – 1827)

Der Kranke, Gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hauff, Hauff, Wilhelm, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

To The Muses

Whether on Ida’s shady brow,

Or in the chambers of the East,

The chambers of the sun, that now

From ancient melody have ceas’d;

Whether in Heav’n ye wander fair,

Or the green corners of the earth,

Or the blue regions of the air,

Where the melodious winds have birth;

Whether on crystal rocks ye rove,

Beneath the bosom of the sea

Wand’ring in many a coral grove,

Fair Nine, forsaking Poetry!

How have you left the ancient love

That bards of old enjoy’d in you!

The languid strings do scarcely move!

The sound is forc’d, the notes are few!

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

To The Muses

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

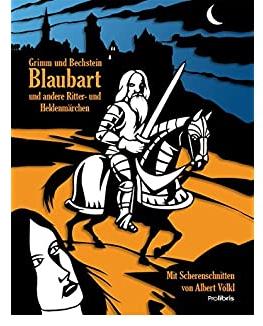

Das Märchen vom Ritter Blaubart

Es war einmal ein gewaltiger Rittersmann, der hatte viel Geld und Gut, und lebte auf seinem Schlosse herrlich und in Freuden. Er hatte einen blauen Bart, davon man ihn nur Ritter Blaubart nannte, obschon er eigentlich anders hieß, aber sein wahrer Name ist verloren gegangen.

Dieser Ritter hatte sich schon mehr als einmal verheiratet, allein man hätte gehört, daß alle seine Frauen schnell nacheinander gestorben seien, ohne daß man eigentlich ihre Krankheit erfahren hatte. Nun ging Ritter Blaubart abermals auf Freiersfüßen, und da war eine Edeldame in seiner Nachbarschaft, die hatte zwei schöne Töchter und einige ritterliche Söhne, und diese Geschwister liebten einander sehr zärtlich. Als nun Ritter Blaubart die eine dieser Töchter heiraten wollte, hatte keine von beiden rechte Lust, denn sie fürchteten sich vor des Ritters blauem Bart, und mochten sich auch nicht gern voneinander trennen. Aber der Ritter lud die Mutter, die Töchter und die Brüder samt und sonders auf sein großes schönes Schloß zu Gaste, und verschaffte ihnen dort so viel angenehmen Zeitvertreib und so viel Vergnügen durch Jagden, Tafeln, Tänze, Spiele und sonstige Freudenfeste, daß sich endlich die jüngste der Schwestern ein Herz faßte, und sich entschloß, Ritter Blaubarts Frau zu werden. Bald darauf wurde auch die Hochzeit mit vieler Pracht gefeiert.

Dieser Ritter hatte sich schon mehr als einmal verheiratet, allein man hätte gehört, daß alle seine Frauen schnell nacheinander gestorben seien, ohne daß man eigentlich ihre Krankheit erfahren hatte. Nun ging Ritter Blaubart abermals auf Freiersfüßen, und da war eine Edeldame in seiner Nachbarschaft, die hatte zwei schöne Töchter und einige ritterliche Söhne, und diese Geschwister liebten einander sehr zärtlich. Als nun Ritter Blaubart die eine dieser Töchter heiraten wollte, hatte keine von beiden rechte Lust, denn sie fürchteten sich vor des Ritters blauem Bart, und mochten sich auch nicht gern voneinander trennen. Aber der Ritter lud die Mutter, die Töchter und die Brüder samt und sonders auf sein großes schönes Schloß zu Gaste, und verschaffte ihnen dort so viel angenehmen Zeitvertreib und so viel Vergnügen durch Jagden, Tafeln, Tänze, Spiele und sonstige Freudenfeste, daß sich endlich die jüngste der Schwestern ein Herz faßte, und sich entschloß, Ritter Blaubarts Frau zu werden. Bald darauf wurde auch die Hochzeit mit vieler Pracht gefeiert.

Nach einer Zeit sagte der Ritter Blaubart zu seiner jungen Frau: »Ich muß verreisen, und übergebe dir die Obhut über das ganze Schloß, Haus und Hof, mit allem, was dazu gehört. Hier sind auch die Schlüssel zu allen Zimmern und Gemächern, in alle diese kannst du zu jeder Zeit eintreten. Aber dieser kleine goldne Schlüssel schließt das hinterste Kabinett am Ende der großen Zimmerreihe. In dieses, meine Teure, muß ich dir verbieten zu gehen, so lieb dir meine Liebe und dein Leben ist. Würdest du dieses Kabinett öffnen, so erwartet dich die schrecklichste Strafe der Neugier. Ich müßte dir dann mit eigner Hand das Haupt vom Rumpfe trennen!« – Die Frau wollte auf diese Rede den kleinen goldnen Schlüssel nicht annehmen, indes mußte sie dies tun, um ihn sicher aufzubewahren, und so schied sie von ihrem Mann mit dem Versprechen, daß es ihr nie einfallen werde, jenes Kabinett aufzuschließen und es zu betreten.

Als der Ritter fort war, erhielt die junge Frau Besuch von ihrer Schwester und ihren Brüdern, die gerne auf die Jagd gingen; und nun wurden mit Lust alle Tage die Herrlichkeiten in den vielen vielen Zimmern des Schlosses durchmustert, und so kamen die Schwestern auch endlich an das Kabinett. Die Frau wollte, obschon sie selbst große Neugierde trug, durchaus nicht öffnen, aber die Schwester lachte ob ihrer Bedenklichkeit, und meinte, daß Ritter Blaubart darin doch nur aus Eigensinn das Kostbarste und Wertvollste von seinen Schätzen verborgen halte. Und so wurde der Schlüssel mit einigem Zagen in das Schloß gesteckt, und da flog auch gleich mit dumpfem Geräusch die Türe auf, und in dem sparsam erhellten Zimmer zeigten sich – ein entsetzlicher Anblick! – die blutigen Häupter aller früheren Frauen Ritter Blaubarts, die ebensowenig, wie die jetzige, dem Drang der Neugier hatten widerstehen können, und die der böse Mann alle mit eigner Hand enthauptet hatte. Vom Tod geschüttelt, wichen jetzt die Frauen und ihre Schwester zurück; vor Schreck war der Frau der Schlüssel entfallen, und als sie ihn aufhob, waren Blutflecke daran, die sich nicht abreiben ließen, und ebensowenig gelang es, die Türe wieder zuzumachen, denn das Schloß war bezaubert, und indem verkündeten Hörner die Ankunft Berittner vor dem Tore der Burg. Die Frau atmete auf und glaubte, es seien ihre Brüder, die sie von der Jagd zurück erwartete, aber es war Ritter Blaubart selbst, der nichts Eiligeres zu tun hatte, als nach seiner Frau zu fragen, und als diese ihm bleich, zitternd und bestürzt entgegentrat, so fragte er nach dem Schlüssel; sie wollte den Schlüssel holen und er folgte ihr auf dem Fuße, und als er die Flecken am Schlüssel sah, so verwandelten sich alle seine Geberden, und er schrie: »Weib, du mußt nun von meinen Händen sterben! Alle Gewalt habe ich dir gelassen! Alles war dein! Reich und schön war dein Leben! Und so gering war deine Liebe zu mir, du schlechte Magd, daß du meine einzige geringe Bitte, meinen ernsten Befehl nicht beachtet hast? Bereite dich zum Tode! Es ist aus mit dir!«

Voll Entsetzen und Todesangst eilte die Frau zu ihrer Schwester, und bat sie, geschwind auf die Turmzinne zu steigen und nach ihren Brüdern zu spähen, und diesen, sobald sie sie erblicke, ein Notzeichen zu geben, während sie sich auf den Boden warf, und zu Gott um ihr Leben flehte. Und dazwischen rief sie: »Schwester! Siehst du noch niemand!« – »Niemand!« klang die trostlose Antwort. – »Weib! komm herunter!« schrie Ritter Blaubart, »deine Frist ist aus!«

Voll Entsetzen und Todesangst eilte die Frau zu ihrer Schwester, und bat sie, geschwind auf die Turmzinne zu steigen und nach ihren Brüdern zu spähen, und diesen, sobald sie sie erblicke, ein Notzeichen zu geben, während sie sich auf den Boden warf, und zu Gott um ihr Leben flehte. Und dazwischen rief sie: »Schwester! Siehst du noch niemand!« – »Niemand!« klang die trostlose Antwort. – »Weib! komm herunter!« schrie Ritter Blaubart, »deine Frist ist aus!«

»Schwester! siehst du niemand?« schrie die Zitternde. »Eine Staubwolke – aber ach, es sind Schafe!« antwortete die Schwester. – »Weib! komm herunter, oder ich hole dich!« schrie Ritter Blaubart.

»Erbarmen! Ich komme ja sogleich! Schwester! siehst du niemand?« – »Zwei Ritter kommen zu Roß daher, sie sahen mein Zeichen, sie reiten wie der Wind.« –

»Weib! Jetzt hole ich dich!« donnerte Blaubarts Stimme, und da kam er die Treppe herauf. Aber die Frau gewann Mut, warf ihre Zimmertüre ins Schloß, und hielt sie fest, und dabei schrie sie samt ihrer Schwester so laut um Hülfe, wie sie beide nur konnten. Indessen eilten die Brüder wie der Blitz herbei, stürmten die Treppe hinauf und kamen eben dazu, wie Ritter Blaubart die Türe sprengte und mit gezücktem Schwert in das Zimmer drang. Ein kurzes Gefecht und Ritter Blaubart lag tot am Boden. Die Frau war erlöst, konnte aber die Folgen ihrer Neugier lange nicht verwinden.

Ludwig Bechstein

(1801 – 1860)

Das Märchen vom Ritter Blaubart

Sämtliche Märchen

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bechstein, Bechstein, Ludwig, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

An Emilie

Zum Garten ging ich früh hinaus,

Ob ich vielleicht ein Sträußchen finde?

Nach manchem Blümchen schaut’ ich aus,

Ich wollt’s für dich zum Angebinde;

Umsonst hatt’ ich mich hinbemüht,

Vergebens war mein freudig Hoffen;

Das Veilchen war schon abgeblüht,

Von andern Blümchen keines offen.

Und trauernd späht’ ich her und hin,

Da tönte zu mir leise, leise

Ein Flüstern aus der Zweige Grün,

Gesang nach sel’ger Geister Weise;

Und lieblich, wie des Morgens Licht

Des Tales Nebelhüllen scheidet,

Ein Röschen aus der Knospe bricht,

Das seine Blätter schnell verbreitet.

»Du suchst ein Blümchen?« spricht’s zu mir,

»So nimm mich hin mit meinen Zweigen,

Bring mich zum Angebinde ihr!

Ich bin der wahren Freude Zeichen.

Ob auch mein Glanz vergänglich sei,

Es treibt aus ihrem treuen Schoße

Die Erde meine Knospen neu,

Drum unvergänglich ist die Rose.

Und wie mein Leben ewig quillt

Und Knosp’ um Knospe sich erschließet,

Wenn mich die Sonne sanft und mild

Mit ihrem Feuerkuß begrüßet,

So deine Freundin ewig blüht,

Beseelt vom Geiste ihrer Lieben,

Denn ob der Rose Schmelz verglüht —

Der Rose Leben ist geblieben.«

Wilhelm Hauff

(1802 – 1827)

An Emilie, Gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Hauff, Hauff, Wilhelm, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Siebenschön

Es waren einmal in einem Dorfe ein paar arme Leute, die hatten ein kleines Häuschen und nur eine einzige Tochter, die war wunderschön und gut über alle Maßen. Sie arbeitete, fegte, wusch, spann und nähte für sieben, und war so schön wie sieben zusammen, darum ward sie Siebenschön geheißen. Aber weil sie ob ihrer Schönheit immer von den Leuten angestaunt wurde, schämte sie sich, und nahm sonntags, wenn sie in die Kirche ging – denn Siebenschön war auch frömmer wie sieben andre, und das war ihre größte Schönheit – einen Schleier vor ihr Gesicht.

So sah sie einstens der Königssohn, und hatte seine Freude über ihre edle Gestalt, ihren herrlichen Wuchs, so schlank wie eine junge Tanne, aber es war ihm leid, daß er vor dem Schleier nicht auch ihr Gesicht sah, und fragte seiner Diener einen: »Wie kommt es, daß wir Siebenschöns Gesicht nicht sehen?« – »Das kommt daher« – antwortete der Diener: »weil Siebenschön so sittsam ist.« Darauf sagte der Königssohn: »Ist Siebenschön so sittsam zu ihrer Schönheit, so will ich sie lieben mein lebenlang und will sie heiraten. Gehe du hin und bringe ihr diesen goldnen Ring von mir und sage ihr, ich habe mit ihr zu reden, sie solle abends zu der großen Eiche kommen.« Der Diener tat wie ihm befohlen war, und Siebenschön glaubte, der Königssohn wolle ein Stück Arbeit bei ihr bestellen, ging daher zur großen Eiche und da sagte ihr der Prinz, daß er sie lieb habe um ihrer großen Sittsamkeit und Tugend willen, und sie zur Frau nehmen wolle; Siebenschön aber sagte: »Ich bin ein armes Mädchen und du bist ein reicher Prinz, dein Vater würde sehr böse werden, wenn du mich wolltest zur Frau nehmen.

So sah sie einstens der Königssohn, und hatte seine Freude über ihre edle Gestalt, ihren herrlichen Wuchs, so schlank wie eine junge Tanne, aber es war ihm leid, daß er vor dem Schleier nicht auch ihr Gesicht sah, und fragte seiner Diener einen: »Wie kommt es, daß wir Siebenschöns Gesicht nicht sehen?« – »Das kommt daher« – antwortete der Diener: »weil Siebenschön so sittsam ist.« Darauf sagte der Königssohn: »Ist Siebenschön so sittsam zu ihrer Schönheit, so will ich sie lieben mein lebenlang und will sie heiraten. Gehe du hin und bringe ihr diesen goldnen Ring von mir und sage ihr, ich habe mit ihr zu reden, sie solle abends zu der großen Eiche kommen.« Der Diener tat wie ihm befohlen war, und Siebenschön glaubte, der Königssohn wolle ein Stück Arbeit bei ihr bestellen, ging daher zur großen Eiche und da sagte ihr der Prinz, daß er sie lieb habe um ihrer großen Sittsamkeit und Tugend willen, und sie zur Frau nehmen wolle; Siebenschön aber sagte: »Ich bin ein armes Mädchen und du bist ein reicher Prinz, dein Vater würde sehr böse werden, wenn du mich wolltest zur Frau nehmen.

« Der Prinz drang aber noch mehr in sie, und da sagte sie endlich, sie wolle sich’s bedenken, er solle ihr ein paar Tage Bedenkzeit gönnen. Der Königssohn konnte aber unmöglich ein paar Tage warten, er schickte schon am folgenden Tage Siebenschön ein Paar silberne Schuhe und ließ sie bitten, noch einmal unter die große Eiche zu kommen. Da sie nun kam, so fragte er schon, ob sie sich besonnen habe? sie aber sagte, sie habe noch keine Zeit gehabt sich zu besinnen, es gebe im Haushalt gar viel zu tun, und sie sei ja doch ein armes Mädchen und er ein reicher Prinz, und sein Vater werde sehr böse werden, wenn er, der Prinz, sie zur Frau nehmen wolle. Aber der Prinz bat von neuem und immermehr, bis Siebenschön versprach, sich gewiß zu bedenken und ihren Eltern zu sagen, was der Prinz im Willen habe. Als der folgende Tag kam, da schickte der Königssohn ihr ein Kleid, das war ganz von Goldstoff, und ließ sie abermals zu der Eiche bitten.

Aber als nun Siebenschön dahin kam, und der Prinz wieder fragte, da mußte sie wieder sagen und klagen, daß sie abermals gar zu viel und den ganzen Tag zu tun gehabt, und keine Zeit zum Bedenken, und daß sie mit ihren Eltern von dieser Sache auch noch nicht habe reden können, und wiederholte auch noch einmal, was sie dem Prinzen schon zweimal gesagt hatte, daß sie arm, er aber reich sei, und daß er seinen Vater nur erzürnen werde. Aber der Prinz sagte ihr, das alles habe nichts auf sich, sie solle nur seine Frau werden, so werde sie später auch Königin, und da sie sah, wie aufrichtig der Prinz es mit ihr meinte, so sagte sie endlich ja, und kam nun jeden Abend zu der Eiche und zu dem Königssohne – auch sollte der König noch nichts davon erfahren. Aber da war am Hofe eine alte häßliche Hofmeisterin, die lauerte dem Königssohn auf, kam hinter sein Geheimnis und sagte es dem Könige an. Der König ergrimmte, sandte Diener aus und ließ das Häuschen, worin Siebenschöns Eltern wohnten, in Brand stecken, damit sie darin anbrenne. Sie tat dies aber nicht, sie sprang als sie das Feuer merkte heraus und alsbald in einen leeren Brunnen hinein, ihre Eltern aber, die armen alten Leute verbrannten in dem Häuschen.

Da saß nun Siebenschön drunten im Brunnen und grämte sich und weinte sehr, konnt’s aber zuletzt doch nicht auf die Länge drunten im Brunnen aushalten, krabbelte herauf, fand im Schutt des Häuschens noch etwas Brauchbares, machte es zu Geld und kaufte dafür Mannskleider, ging als ein frischer Bub an des Königs Hof und bot sich zu einem Bedienten an. Der König fragte den jungen Diener nach dem Namen, da erhielt er die Antwort: »Unglück!« und dem König gefiel der junge Diener also wohl, daß er ihn gleich annahm, und auch bald vor allen andern Dienern gut leiden konnte.

Da saß nun Siebenschön drunten im Brunnen und grämte sich und weinte sehr, konnt’s aber zuletzt doch nicht auf die Länge drunten im Brunnen aushalten, krabbelte herauf, fand im Schutt des Häuschens noch etwas Brauchbares, machte es zu Geld und kaufte dafür Mannskleider, ging als ein frischer Bub an des Königs Hof und bot sich zu einem Bedienten an. Der König fragte den jungen Diener nach dem Namen, da erhielt er die Antwort: »Unglück!« und dem König gefiel der junge Diener also wohl, daß er ihn gleich annahm, und auch bald vor allen andern Dienern gut leiden konnte.

Als der Königssohn erfuhr, daß Siebenschöns Häuschen verSiebenschönbrannt war, wurde er sehr traurig, glaubte nicht anders, als Siebenschön sei mit verbrannt, und der König glaubte[180] das auch, und wollte haben, daß sein Sohn nun endlich eine Prinzessin heirate, und mußte dieser nun eines benachbarten Königs Tochter freien. Da mußte auch der ganze Hof und die ganze Dienerschaft mir zur Hochzeit ziehen, und für Unglück war das am traurigsten, es lag ihm wie ein Stein auf dem Herzen. Er ritt auch mit hintennach der Letzte im Zuge, und sang wehklagend mit klarer Stimme:

»Siebenschön war ich genannt,

Unglück ist mir jetzt bekannt.«

Das hörte der Prinz von weitem, und fiel ihm auf und hielt und fragte: »Ei wer singt doch da so schön?« – »Es wird wohl mein Bedienter, der Unglück sein«, antwortete der König, »den ich zum Diener angenommen habe.« Da hörten sie noch einmal den Gesang:

»Siebenschön war ich genannt,

Unglück ist mir jetzt bekannt.«

Da fragte der Prinz noch einmal, ob das wirklich niemand anders sei, als des Königs Diener? und der König sagte er wisse es nicht anders.

Als nun der Zug ganz nahe an das Schloß der neuen Braut kam, erklang noch einmal die schöne klare Stimme:

»Siebenschon war ich genannt,

Unglück ist mir jetzt bekannt.«

Jetzt wartete der Prinz keinen Augenblick länger, er spornte sein Pferd und ritt wie ein Offizier längs des ganzen Zugs in gestrecktem Galopp hin, bis er an Unglück kam, und Siebenschön erkannte. Da nickte er ihr freundlich zu und jagte wieder an die Spitze des Zuges, und zog in das Schloß ein. Da nun alle Gäste und alles Gefolge im großen Saal versammelt war und die Verlobung vor sich gehen sollte, so sagte der Prinz zu seinem künftigen Schwiegervater: »Herr König, ehe ich mit Eurer Prinzessin Tochter mich feierlich verlobe, wollet mir erst ein kleines Rätsel lösen. Ich besitze einen schönen Schrank, dazu verlor ich vor einiger Zeit den Schlüssel, kaufte mir also einen neuen; bald darauf fand ich den alten wieder, jetzt saget mir Herr König, wessen Schlüssel ich mich bedienen soll?« – »Ei natürlich des alten wieder!« antwortete der König, »das Alte soll man in Ehren halten, und es über Neuem nicht hintansetzen.« – »Ganz wohl Herr König«, antwortete nun der Prinz, »so zürnt mir nicht, wenn ich Eure Prinzessin Tochter nicht freien kann, sie ist der neue Schlüssel, und dort steht der alte.« Und nahm Siebenschön an der Hand und führte sie zu seinem Vater, indem er sagte: »Siehe Vater, das ist meine Braut.« Aber der alte König rief ganz erstaunt und erschrocken aus: »Ach lieber Sohn, das ist ja Unglück, mein Diener!« – Und viele Hofleute schrieen: »Herr Gott, das ist ja ein Unglück!« – »Nein!« sagte der Königssohn, »hier ist gar kein Unglück, sondern hier ist Siebenschön, meine liebe Braut.« Und nahm Urlaub von der Versammlung und führte Siebenschön als Herrin und Frau auf sein schönstes Schloß.

Jetzt wartete der Prinz keinen Augenblick länger, er spornte sein Pferd und ritt wie ein Offizier längs des ganzen Zugs in gestrecktem Galopp hin, bis er an Unglück kam, und Siebenschön erkannte. Da nickte er ihr freundlich zu und jagte wieder an die Spitze des Zuges, und zog in das Schloß ein. Da nun alle Gäste und alles Gefolge im großen Saal versammelt war und die Verlobung vor sich gehen sollte, so sagte der Prinz zu seinem künftigen Schwiegervater: »Herr König, ehe ich mit Eurer Prinzessin Tochter mich feierlich verlobe, wollet mir erst ein kleines Rätsel lösen. Ich besitze einen schönen Schrank, dazu verlor ich vor einiger Zeit den Schlüssel, kaufte mir also einen neuen; bald darauf fand ich den alten wieder, jetzt saget mir Herr König, wessen Schlüssel ich mich bedienen soll?« – »Ei natürlich des alten wieder!« antwortete der König, »das Alte soll man in Ehren halten, und es über Neuem nicht hintansetzen.« – »Ganz wohl Herr König«, antwortete nun der Prinz, »so zürnt mir nicht, wenn ich Eure Prinzessin Tochter nicht freien kann, sie ist der neue Schlüssel, und dort steht der alte.« Und nahm Siebenschön an der Hand und führte sie zu seinem Vater, indem er sagte: »Siehe Vater, das ist meine Braut.« Aber der alte König rief ganz erstaunt und erschrocken aus: »Ach lieber Sohn, das ist ja Unglück, mein Diener!« – Und viele Hofleute schrieen: »Herr Gott, das ist ja ein Unglück!« – »Nein!« sagte der Königssohn, »hier ist gar kein Unglück, sondern hier ist Siebenschön, meine liebe Braut.« Und nahm Urlaub von der Versammlung und führte Siebenschön als Herrin und Frau auf sein schönstes Schloß.

Ludwig Bechstein

(1801 – 1860)

Siebenschön

Sämtliche Märchen

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bechstein, Bechstein, Ludwig, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Ah! Would I Could Forget

The whispering water rocks the reeds,

And, murmuring softly, laps the weeds;

And nurses there the falsest bloom

That ever wrought a lover’s doom.

Forget me not! Forget me not!

Ah! would I could forget!

But, crying still, “Forget me not,”

Her image haunts me yet.

We wander’d by the river’s brim,

The day grew dusk, the pathway dim;

Her eyes like stars dispell’d the gloom,

Her gleaming fingers pluck’d the bloom.

Forget me not! Forget me not!

Ah! would I could forget!

But, crying still, “Forget me not,”

Her image haunts me yet.

The pale moon lit her paler face,

And coldly watch’d our last embrace,

And chill’d her tresses’ sunny hue,

And stole that flower’s turquoise blue.

Forget me not! Forget me not!

Ah! would I could forget!

But, crying still, “Forget me not,”

Her image haunts me yet.

The fateful flower droop’d to death,

The fair, false maid forswore her faith;

But I obey a broken vow,

And keep those wither’d blossoms now!

Forget me not! Forget me not!

Ah! would I could forget!

But, crying still, “Forget me not,”

Her image haunts me yet.

Sweet lips that pray’d–“Forget me not!”

Sweet eyes that will not be forgot!

Recall your prayer, forego your power,

Which binds me by the fatal flower.

Forget me not! Forget me not!

Ah! would I could forget!

But, crying still, “Forget me not,”

Her image haunts me yet.

Juliana Horatia Ewing

(1841–1885)

Poem

Ah! Would I Could Forget

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Archive E-F, Juliana Horatia Ewing, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

“One fatal remembrance, one sorrow that throws

Its bleak shade alike o’er our joys and our woes,

To which life nothing darker or brighter can bring,

For which joy has no balm, and affliction no sting!”

—Moore.

A gorgeous scene of kingly pride is the prospect now before us!—the offspring of art, the nursling of nature—where can the eye rest on a landscape more deliciously lovely than the fair expanse of Virginia Water, now an open mirror to the sky, now shaded by umbrageous banks, which wind into dark recesses, or are rounded into soft promontories?

Looking down on it, now that the sun is low in the west, the eye is dazzled, the soul oppressed, by excess of beauty. Earth, water, air drink to overflowing the radiance that streams from yonder well of light; the foliage of the trees seems dripping with the golden flood; while the lake, filled with no earthly dew, appears but an imbasining of the sun-tinctured atmosphere; and trees and gay pavilion float in its depth, more dear, more distinct than their twins in the upper air. Nor is the scene silent: strains more sweet than those that lull Venus to her balmy rest, more inspiring than the song of Tiresias which awoke Alexander to the deed of ruin, more solemn than the chantings of St. Cecilia, float along the waves and mingle with the lagging breeze, which ruffles not the lake. Strange, that a few dark scores should be the key to this fountain of sound; the unconscious link between unregarded noise and harmonies which unclose paradise to our entranced senses!

The sun touches the extreme boundary, and a softer, milder light mingles a roseate tinge with the fiery glow. Our boat has floated long on the broad expanse; now let it approach the umbrageous bank. The green tresses of the graceful willow dip into the waters, which are checked by them into a ripple. The startled teal dart from their recess, skimming the waves with splashing wing. The stately swans float onward; while innumerable waterfowl cluster together out of the way of the oars. The twilight is blotted by no dark shades; it is one subdued, equal receding of the great tide of day. We may disembark, and wander yet amid the glades, long before the thickening shadows speak of night. The plantations are formed of every English tree, with an old oak or two standing out in the walks. There the glancing foliage obscures heaven, as the silken texture of a veil a woman’s lovely features. Beneath such fretwork we may indulge in light-hearted thoughts; or, if sadder meditations lead us to seek darker shades, we may pass the cascade towards the large groves of pine, with their vast undergrowth of laurel, reaching up to the Belvidere; or, on the opposite side of the water, sit under the shadow of the silver-stemmed birch, or beneath the leafy pavilions of those fine old beeches, whose high fantastic roots seem formed in nature’s sport; and the near jungle of sweet-smelling myrica leaves no sense unvisited by pleasant ministration.

The sun touches the extreme boundary, and a softer, milder light mingles a roseate tinge with the fiery glow. Our boat has floated long on the broad expanse; now let it approach the umbrageous bank. The green tresses of the graceful willow dip into the waters, which are checked by them into a ripple. The startled teal dart from their recess, skimming the waves with splashing wing. The stately swans float onward; while innumerable waterfowl cluster together out of the way of the oars. The twilight is blotted by no dark shades; it is one subdued, equal receding of the great tide of day. We may disembark, and wander yet amid the glades, long before the thickening shadows speak of night. The plantations are formed of every English tree, with an old oak or two standing out in the walks. There the glancing foliage obscures heaven, as the silken texture of a veil a woman’s lovely features. Beneath such fretwork we may indulge in light-hearted thoughts; or, if sadder meditations lead us to seek darker shades, we may pass the cascade towards the large groves of pine, with their vast undergrowth of laurel, reaching up to the Belvidere; or, on the opposite side of the water, sit under the shadow of the silver-stemmed birch, or beneath the leafy pavilions of those fine old beeches, whose high fantastic roots seem formed in nature’s sport; and the near jungle of sweet-smelling myrica leaves no sense unvisited by pleasant ministration.

Now this splendid scene is reserved for the royal possessor; but in past years; while the lodge was called the Regent’s Cottage, or before, when the under-ranger inhabited it, the mazy paths of Chapel Wood were open, and the iron gates enclosing the plantations and Virginia Water were guarded by no Cerebus untamable by sops. It was here, on a summer’s evening, that Horace Neville and his two fair cousins floated idly on the placid lake,

“In that sweet mood when pleasant thoughts

Bring sad thoughts to the mind.”

Neville had been eloquent in praise of English scenery. “In distant climes,” he said, “we may find landscapes grand in barbaric wildness, or rich in the luxuriant vegetation of the south, or sublime in Alpine magnificence. We may lament, though it is ungrateful to say so on such a night as this, the want of a more genial sky; but where find scenery to be compared to the verdant, well-wooded, well-watered groves of our native land; the clustering cottages, shadowed by fine old elms; each garden blooming with early flowers, each lattice gay with geraniums and roses; the blue-eyed child devouring his white bread, while he drives a cow to graze; the hedge redolent with summer blooms; the enclosed cornfields, seas of golden grain, weltering in the breeze; the stile, the track across the meadow, leading through the copse, under which the path winds, and the meeting branches overhead, which give, by their dimming tracery, a cathedral-like solemnity to the scene; the river, winding ‘with sweet inland murmur;’ and, as additional graces, spots like these—oases of taste—gardens of Eden—the works of wealth, which evince at once the greatest power and the greatest will to create beauty?

“And yet,” continued Neville, “it was with difficulty that I persuaded myself to reap the best fruits of my uncle’s will, and to inhabit this spot, familiar to my boyhood, associated with unavailing regrets and recollected pain.”

Horace Neville was a man of birth—of wealth; but he could hardly be termed a man of the world. There was in his nature a gentleness, a sweetness, a winning sensibility, allied to talent and personal distinction, that gave weight to his simplest expressions, and excited sympathy for all his emotions. His younger cousin, his junior by several years, was attached to him by the tenderest sentiments—secret long—but they were now betrothed to each other—a lovely, happy pair. She looked inquiringly, but he turned away. “No more of this,” he said, and, giving a swifter impulse to their boat, they speedily reached the shore, landed, and walked through the long extent of Chapel Wood. It was dark night before they met their carriage at Bishopsgate.

A week or two after, Horace received letters to call him to a distant part of the country. A few days before his departure, he requested his cousin to walk with him. They bent their steps across several meadows to Old Windsor Churchyard. At first he did not deviate from the usual path; and as they went they talked cheerfully—gaily. The beauteous sunny day might well exhilarate them; the dancing waves sped onwards at their feet; the country church lifted its rustic spire into the bright pure sky. There was nothing in their conversation that could induce his cousin to think that Neville had led her hither for any saddening purpose; but when they were about to quit the churchyard, Horace, as if he had suddenly recollected himself, turned from the path, crossed the greensward, and paused beside a grave near the river. No stone was there to commemorate the being who reposed beneath—it was thickly grown with grass, starred by a luxuriant growth of humble daisies: a few dead leaves, a broken bramble twig, defaced its neatness. Neville removed these, and then said, “Juliet, I commit this sacred spot to your keeping while I am away.”

“There is no monument,” he continued; “for her commands were implicitly obeyed by the two beings to whom she addressed them. One day another may lie near, and his name will be her epitaph. I do not mean myself,” he said, half-smiling at the terror his cousin’s countenance expressed; “but promise me, Juliet, to preserve this grave from every violation. I do not wish to sadden you by the story; yet, if I have excited your interest, I will satisfy it; but not now—not here.”

It was not till the following day, when, in company with her sister, they again visited Virginia Water, that, seated under the shadow of its pines, whose melodious swinging in the wind breathed unearthly harmony, Neville, unasked, commenced his story.

“I was sent to Eton at eleven years of age. I will not dwell upon my sufferings there; I would hardly refer to them, did they not make a part of my present narration. I was a fag to a hard taskmaster; every labour he could invent—and the youthful tyrant was ingenious—he devised for my annoyance; early and late, I was forced to be in attendance, to the neglect of my school duties, so incurring punishment. There were worse things to bear than these: it was his delight to put me to shame, and, finding that I had too much of my mother in my blood,—to endeavour to compel me to acts of cruelty from which my nature revolted,—I refused to obey. Speak of West Indian slavery! I hope things may be better now; in my days, the tender years of aristocratic childhood were yielded up to a capricious, unrelenting, cruel bondage, far beyond the measured despotism of Jamaica.

“One day—I had been two years at school, and was nearly thirteen—my tyrant, I will give him no other name, issued a command, in the wantonness of power, for me to destroy a poor little bullfinch I had tamed and caged. In a hapless hour he found it in my room, and was indignant that I should dare to appropriate a single pleasure. I refused, stubbornly, dauntlessly, though the consequence of my disobedience was immediate and terrible. At this moment a message came from my tormentor’s tutor—his father had arrived. ‘Well, old lad,’ he cried, ‘I shall pay you off some day!’ Seizing my pet at the same time, he wrung its neck, threw it at my feet, and, with a laugh of derision, quitted the room.

“Never before—never may I again feel the same swelling, boiling fury in my bursting heart;—the sight of my nursling expiring at my feet—my desire of vengeance—my impotence, created a Vesuvius within me, that no tears flowed to quench. Could I have uttered—acted—my passion, it would have been less torturous: it was so when I burst into a torrent of abuse and imprecation. My vocabulary—it must have been a choice collection—was supplied by him against whom it was levelled. But words were air. I desired to give more substantial proof of my resentment—I destroyed everything in the room belonging to him; I tore them to pieces, I stamped on them, crushed them with more than childish strength. My last act was to seize a timepiece, on which my tyrant infinitely prided himself, and to dash it to the ground. The sight of this, as it lay shattered at my feet, recalled me to my senses, and something like an emotion of fear allayed the tumult in my heart. I began to meditate an escape: I got out of the house, ran down a lane, and across some meadows, far out of bounds, above Eton. I was seen by an elder boy, a friend of my tormentor. He called to me, thinking at first that I was performing some errand for him; but seeing that I shirked, he repeated his ‘Come up!’ in an authoritative voice. It put wings to my heels; he did not deem it necessary to pursue. But I grow tedious, my dear Juliet; enough that fears the most intense, of punishment both from my masters and the upper boys, made me resolve to run away. I reached the banks of the Thames, tied my clothes over my head, swam across, and, traversing several fields, entered Windsor Forest, with a vague childish feeling of being able to hide myself for ever in the unexplored obscurity of its immeasurable wilds. It was early autumn; the weather was mild, even warm; the forest oaks yet showed no sign of winter change, though the fern beneath wore a yellowy tinge. I got within Chapel Wood; I fed upon chestnuts and beechnuts; I continued to hide myself from the gamekeepers and woodmen. I lived thus two days.

“But chestnuts and beechnuts were sorry fare to a growing lad of thirteen years old. A day’s rain occurred, and I began to think myself the most unfortunate boy on record. I had a distant, obscure idea of starvation: I thought of the Children in the Wood, of their leafy shroud, gift of the pious robin; this brought my poor bullfinch to my mind, and tears streamed in torrents down my cheeks. I thought of my father and mother; of you, then my little baby cousin and playmate; and I cried with renewed fervour, till, quite exhausted, I curled myself up under a huge oak among some dry leaves, the relics of a hundred summers, and fell asleep.

“I ramble on in my narration as if I had a story to tell; yet I have little except a portrait—a sketch—to present, for your amusement or interest. When I awoke, the first object that met my opening eyes was a little foot, delicately clad in silk and soft kid. I looked up in dismay, expecting to behold some gaily dressed appendage to this indication of high-bred elegance; but I saw a girl, perhaps seventeen, simply clad in a dark cotton dress, her face shaded by a large, very coarse straw hat; she was pale even to marmoreal whiteness; her chestnut-coloured hair was parted in plain tresses across a brow which wore traces of extreme suffering; her eyes were blue, full, large, melancholy, often even suffused with tears; but her mouth had an infantine sweetness and innocence in its expression, that softened the otherwise sad expression of her countenance.

“She spoke to me. I was too hungry, too exhausted, too unhappy, to resist her kindness, and gladly permitted her to lead me to her home. We passed out of the wood by some broken palings on to Bishopsgate Heath, and after no long walk arrived at her habitation. It was a solitary, dreary-looking cottage; the palings were in disrepair, the garden waste, the lattices unadorned by flowers or creepers; within, all was neat, but sombre, and even mean. The diminutiveness of a cottage requires an appearance of cheerfulness and elegance to make it pleasing; the bare floor,—clean, it is true,—the rush chairs, deal table, checked curtains of this cot, were beneath even a peasant’s rusticity; yet it was the dwelling of my lovely guide, whose little white hand, delicately gloved, contrasted with her unadorned attire, as did her gentle self with the clumsy appurtenances of her too humble dwelling.

“Poor child! she had meant entirely to hide her origin, to degrade herself to a peasant’s state, and little thought that she for ever betrayed herself by the strangest incongruities. Thus, the arrangements of her table were mean, her fare meagre for a hermit; but the linen was matchlessly fine, and wax lights stood in candlesticks which a beggar would almost have disdained to own. But I talk of circumstances I observed afterwards; then I was chiefly aware of the plentiful breakfast she caused her single attendant, a young girl, to place before me, and of the sweet soothing voice of my hostess, which spoke a kindness with which lately I had been little conversant. When my hunger was appeased, she drew my story from me, encouraged me to write to my father, and kept me at her abode till, after a few days, I returned to school pardoned. No long time elapsed before I got into the upper forms, and my woful slavery ended.

“Whenever I was able, I visited my disguised nymph. I no longer associated with my schoolfellows; their diversions, their pursuits appeared vulgar and stupid to me; I had but one object in view—to accomplish my lessons, and to steal to the cottage of Ellen Burnet.

“Do not look grave, love! true, others as young as I then was have loved, and I might also; but not Ellen. Her profound, her intense melancholy, sister to despair—her serious, sad discourse—her mind, estranged from all worldly concerns, forbade that; but there was an enchantment in her sorrow, a fascination in her converse, that lifted me above commonplace existence; she created a magic circle, which I entered as holy ground: it was not akin to heaven, for grief was the presiding spirit; but there was an exaltation of sentiment, an enthusiasm, a view beyond the grave, which made it unearthly, singular, wild, enthralling. You have often observed that I strangely differ from all other men; I mingle with them, make one in their occupations and diversions, but I have a portion of my being sacred from them:—a living well, sealed up from their contamination, lies deep in my heart—it is of little use, but there it is; Ellen opened the spring, and it has flowed ever since.

“Of what did she talk? She recited no past adventures, alluded to no past intercourse with friend or relative; she spoke of the various woes that wait on humanity, on the intricate mazes of life, on the miseries of passion, of love, remorse, and death, and that which we may hope or fear beyond the tomb; she spoke of the sensation of wretchedness alive in her own broken heart, and then she grew fearfully eloquent, till, suddenly pausing, she reproached herself for making me familiar with such wordless misery. ‘I do you harm,’ she often said; ‘I unfit you for society; I have tried, seeing you thrown upon yonder distorted miniature of a bad world, to estrange you from its evil contagion; I fear that I shall be the cause of greater harm to you than could spring from association with your fellow-creatures in the ordinary course of things. This is not well—avoid the stricken deer.’

“There were darker shades in the picture than those which I have already developed. Ellen was more miserable than the imagination of one like you, dear girl, unacquainted with woe, can portray. Sometimes she gave words to her despair—it was so great as to confuse the boundary between physical and mental sensation—and every pulsation of her heart was a throb of pain. She has suddenly broken off in talking of her sorrows, with a cry of agony—bidding me leave her—hiding her face on her arms, shivering with the anguish some thought awoke. The idea that chiefly haunted her, though she earnestly endeavoured to put it aside, was self-destruction—to snap the silver cord that bound together so much grace, wisdom, and sweetness—to rob the world of a creation made to be its ornament. Sometimes her piety checked her; oftener a sense of unendurable suffering made her brood with pleasure over the dread resolve. She spoke of it to me as being wicked; yet I often fancied this was done rather to prevent her example from being of ill effect to me, than from any conviction that the Father of all would regard angrily the last act of His miserable child. Once she had prepared the mortal beverage; it was on the table before her when I entered; she did not deny its nature, she did not attempt to justify herself; she only besought me not to hate her, and to soothe by my kindness her last moments.—‘I cannot live!’ was all her explanation, all her excuse; and it was spoken with such fervent wretchedness that it seemed wrong to attempt to persuade her to prolong the sense of pain. I did not act like a boy; I wonder I did not; I made one simple request, to which she instantly acceded, that she should walk with me to this Belvidere. It was a glorious sunset; beauty and the spirit of love breathed in the wind, and hovered over the softened hues of the landscape. ‘Look, Ellen,’ I cried, ‘if only such loveliness of nature existed, it were worth living for!’

“‘True, if a latent feeling did not blot this glorious scene with murky shadows. Beauty is as we see it—my eyes view all things deformed and evil.’ She closed them as she said this; but, young and sensitive, the visitings of the soft breeze already began to minister consolation. ‘Dearest Ellen,’ I continued, ‘what do I not owe to you? I am your boy, your pupil; I might have gone on blindly as others do, but you opened my eyes; you have given me a sense of the just, the good, the beautiful—and have you done this merely for my misfortune? If you leave me, what can become of me?’ The last words came from my heart, and tears gushed from my eyes. ‘Do not leave me, Ellen,’ I said; ‘I cannot live without you—and I cannot die, for I have a mother—a father.’ She turned quickly round, saying, ‘You are blessed sufficiently.’ Her voice struck me as unnatural; she grew deadly pale as she spoke, and was obliged to sit down. Still I clung to her, prayed, cried; till she—I had never seen her shed a tear before—burst into passionate weeping. After this she seemed to forget her resolve. We returned by moonlight, and our talk was even more calm and cheerful than usual. When in her cottage, I poured away the fatal draught. Her ‘good-night’ bore with it no traces of her late agitation; and the next day she said, ‘I have thoughtlessly, even wickedly, created a new duty to myself, even at a time when I had forsworn all; but I will be true to it. Pardon me for making you familiar with emotions and scenes so dire; I will behave better—I will preserve myself if I can, till the link between us is loosened, or broken, and I am free again.’

“One little incident alone occurred during our intercourse that appeared at all to connect her with the world. Sometimes I brought her a newspaper, for those were stirring times; and though, before I knew her, she had forgotten all except the world her own heart enclosed, yet, to please me, she would talk of Napoleon—Russia, from whence the emperor now returned overthrown—and the prospect of his final defeat. The paper lay one day on her table; some words caught her eye; she bent eagerly down to read them, and her bosom heaved with violent palpitation; but she subdued herself, and after a few moments told me to take the paper away. Then, indeed, I did feel an emotion of even impertinent inquisitiveness; I found nothing to satisfy it—though afterwards I became aware that it contained a singular advertisement, saying, ‘If these lines meet the eye of any one of the passengers who were on board the St. Mary, bound for Liverpool from Barbadoes, which sailed on the third of May last, and was destroyed by fire in the high seas, a part of the crew only having been saved by his Majesty’s frigate the Bellerophon, they are entreated to communicate with the advertiser; and if any one be acquainted with the particulars of the Hon. Miss Eversham’s fate and present abode, they are earnestly requested to disclose them, directing to L. E., Stratton Street, Park Lane.’

“It was after this event, as winter came on, that symptoms of decided ill-health declared themselves in the delicate frame of my poor Ellen. I have often suspected that, without positively attempting her life, she did many things that tended to abridge it and to produce mortal disease. Now, when really ill, she refused all medical attendance; but she got better again, and I thought her nearly well when I saw her for the last time, before going home for the Christmas holidays. Her manner was full of affection: she relied, she said, on the continuation of my friendship; she made me promise never to forget her, though she refused to write to me, and forbade any letters from me.

“Even now I see her standing at her humble doorway. If an appearance of illness and suffering can ever he termed lovely, it was in her. Still she was to be viewed as the wreck of beauty. What must she not have been in happier days, with her angel expression of face, her nymph-like figure, her voice, whose tones were music? ‘So young—so lost!’ was the sentiment that burst even from me, a young lad, as I waved my hand to her as a last adieu. She hardly looked more than fifteen, but none could doubt that her very soul was impressed by the sad lines of sorrow that rested so unceasingly on her fair brow. Away from her, her figure for ever floated before my eyes;—I put my hands before them, still she was there: my day, my night dreams were filled by my recollections of her.

“During the winter holidays, on a fine soft day, I went out to hunt: you, dear Juliet, will remember the sad catastrophe; I fell and broke my leg. The only person who saw me fall was a young man who rode one of the most beautiful horses I ever saw, and I believe it was by watching him as he took a leap, that I incurred my disaster: he dismounted, and was at my side in a minute. My own animal had fled; he called his; it obeyed his voice; with ease he lifted my light figure on to the saddle, contriving to support my leg, and so conducted me a short distance to a lodge situated in the woody recesses of Elmore Park, the seat of the Earl of D——, whose second son my preserver was. He was my sole nurse for a day or two, and during the whole of my illness passed many hours of each day by my bedside. As I lay gazing on him, while he read to me, or talked, narrating a thousand stranger adventures which had occurred during his service in the Peninsula, I thought—is it for ever to be my fate to fall in with the highly gifted and excessively unhappy?

“The immediate neighbour of Lewis’ family was Lord Eversham. He had married in very early youth, and became a widower young. After this misfortune, which passed like a deadly blight over his prospects and possessions, leaving the gay view utterly sterile and bare, he left his surviving infant daughter under the care of Lewis’ mother, and travelled for many years in far distant lands. He returned when Clarice was about ten, a lovely sweet child, the pride and delight of all connected with her. Lord Eversham, on his return—he was then hardly more than thirty—devoted himself to her education. They were never separate: he was a good musician, and she became a proficient under his tutoring. They rode—walked—read together. When a father is all that a father may be, the sentiments of filial piety, entire dependence, and perfect confidence being united, the love of a daughter is one of the deepest and strongest, as it is the purest passion of which our natures are capable. Clarice worshipped her parent, who came, during the transition from mere childhood to the period when reflection and observation awaken, to adorn a commonplace existence with all the brilliant adjuncts which enlightened and devoted affection can bestow. He appeared to her like an especial gift of Providence, a guardian angel—but far dearer, as being akin to her own nature. She grew, under his eye, in loveliness and refinement both of intellect and heart. These feelings were not divided—almost strengthened, by the engagement that had taken place between her and Lewis:—Lewis was destined for the army, and, after a few years’ service, they were to be united.

“It is hard, when all is fair and tranquil, when the world, opening before the ardent gaze of youth, looks like a well-kept demesne, unencumbered by let or hindrance for the annoyance of the young traveller, that we should voluntarily stray into desert wilds and tempest-visited districts. Lewis Elmore was ordered to Spain; and, at the same time, Lord Eversham found it necessary to visit some estates he possessed in Barbadoes. He was not sorry to revisit a scene, which had dwelt in his memory as an earthly paradise, nor to show to his daughter a new and strange world, so to form her understanding and enlarge her mind. They were to return in three months, and departed as on a summer tour. Clarice was glad that, while her lover gathered experience and knowledge in a distant land, she should not remain in idleness; she was glad that there would be some diversion for her anxiety during his perilous absence; and in every way she enjoyed the idea of travelling with her beloved father, who would fill every hour, and adorn every new scene, with pleasure and delight. They sailed. Clarice wrote home, with enthusiastic expressions of rapture and delight, from Madeira:—yet, without her father, she said, the fair scene had been blank to her. More than half her letter was filled by the expressions of her gratitude and affection for her adored and revered parent. While he, in his, with fewer words, perhaps, but with no less energy, spoke of his satisfaction in her improvement, his pride in her beauty, and his grateful sense of her love and kindness.

“Such were they, a matchless example of happiness in the dearest connection in life, as resulting from the exercise of their reciprocal duties and affections. A father and daughter; the one all care, gentleness, and sympathy, consecrating his life for her happiness; the other fond, duteous, grateful:—such had they been,—and where were they now,—the noble, kind, respected parent, and the beloved and loving child! They had departed from England as on a pleasure voyage down an inland stream; but the ruthless car of destiny had overtaken them on their unsuspecting way, crushing them under its heavy wheels—scattering love, hope, and joy as the bellowing avalanche overwhelms and grinds to mere spray the streamlet of the valley. They were gone; but whither? Mystery hung over the fate of the most helpless victim; and my friend’s anxiety was, to penetrate the clouds that hid poor Clarice from his sight.

“After an absence of a few months, they had written, fixing their departure in the St. Mary, to sail from Barbadoes in a few days. Lewis, at the same time, returned from Spain: he was invalided, in his very first action, by a bad wound in his side. He arrived, and each day expected to hear of the landing of his friends, when that common messenger, the newspaper, brought him tidings to fill him with more than anxiety—with fear and agonizing doubt. The St. Mary had caught fire, and had burned in the open sea. A frigate, the Bellerophon, had saved a part of the crew. In spite of illness and a physician’s commands, Lewis set out the same day for London to ascertain as speedily as possible the fate of her he loved. There he heard that the frigate was expected in the Downs. Without alighting from his travelling chaise, he posted thither, arriving in a burning fever. He went on board, saw the commander, and spoke with the crew. They could give him few particulars as to whom they had saved; they had touched at Liverpool, and left there most of the persons, including all the passengers rescued from the St. Mary. Physical suffering for awhile disabled Mr. Elmore; he was confined by his wound and consequent fever, and only recovered to give himself up to his exertions to discover the fate of his friends;—they did not appear nor write; and all Lewis’ inquiries only tended to confirm his worst fears; yet still he hoped, and still continued indefatigable in his perquisitions. He visited Liverpool and Ireland, whither some of the passengers had gone, and learnt only scattered, incongruous details of the fearful tragedy, that told nothing of Miss Eversham’s present abode, though much that confirmed his suspicion that she still lived.

“The fire on board the St. Mary had raged long and fearfully before the Bellerophon hove in sight, and boats came off for the rescue of the crew. The women were to be first embarked; but Clarice clung to her father, and refused to go till he should accompany her. Some fearful presentiment that, if she were saved, he would remain and die, gave such energy to her resolve, that not the entreaties of her father, nor the angry expostulations of the captain, could shake it. Lewis saw this man, after the lapse of two or three months, and he threw most light on the dark scene. He well remembered that, transported with anger by her obstinacy, he had said to her, ‘You will cause your father’s death—and be as much a parricide as if you put poison into his cup; you are not the first girl who has murdered her father in her wilful mood.’ Still Clarice passionately refused to go—there was no time for long parley—the point was yielded, and she remained pale, but firm, near her parent, whose arm was around her, supporting her during the awful interval. It was no period for regular action and calm order; a tempest was rising, the scorching waves blew this way and that, making a fearful day of the night which veiled all except the burning ship. The boats returned with difficulty, and one only could contrive to approach; it was nearly full; Lord Eversham and his daughter advanced to the deck’s edge to get in. ‘We can only take one of you,’ vociferated the sailors; ‘keep back on your life! throw the girl to us—we will come back for you if we can.’ Lord Eversham cast with a strong arm his daughter, who had now entirely lost her self-possession, into the boat; she was alive again in a minute; she called to her father, held out her arms to him, and would have thrown herself into the sea, but was held back by the sailors. Meanwhile Lord Eversham, feeling that no boat could again approach the lost vessel, contrived to heave a spar overboard, and threw himself into the sea, clinging to it. The boat, tossed by the huge waves, with difficulty made its way to the frigate; and as it rose from the trough of the sea, Clarice saw her father struggling with his fate—battling with the death that at last became the victor; the spar floated by, his arms had fallen from it; were those his pallid features? She neither wept nor fainted, but her limbs grew rigid, her face colourless, and she was lifted as a log on to the deck of the frigate.

“The captain allowed that on her homeward voyage the people had rather a horror of her, as having caused her father’s death; her own servants had perished, few people remembered who she was; but they talked together with no careful voices as they passed her, and a hundred times she must have heard herself accused of having destroyed her parent. She spoke to no one, or only in brief reply when addressed; to avoid the rough remonstrances of those around, she appeared at table, ate as well as she could; but there was a settled wretchedness in her face that never changed. When they landed at Liverpool, the captain conducted her to an hotel; he left her, meaning to return, but an opportunity of sailing that night for the Downs occurred, of which he availed himself, without again visiting her. He knew, he said, and truly, that she was in her native country, where she had but to write a letter to gather crowds of friends about her; and where can greater civility be found than at an English hotel, if it is known that you are perfectly able to pay your bill?

“This was all that Mr. Elmore could learn, and it took many months to gather together these few particulars. He went to the hotel at Liverpool. It seemed that as soon as there appeared some hope of rescue from the frigate, Lord Eversham had given his pocket-book to his daughter’s care, containing bills on a banking-house at Liverpool to the amount of a few hundred pounds. On the second day after Clarice’s arrival there, she had sent for the master of the hotel, and showed him these. He got the cash for her; and the next day she quitted Liverpool in a little coasting vessel. In vain Lewis endeavoured to trace her. Apparently she had crossed to Ireland; but whatever she had done, wherever she had gone, she had taken infinite pains to conceal herself, and all due was speedily lost.

“Lewis had not yet despaired; he was even now perpetually making journeys, sending emissaries, employing every possible means for her discovery. From the moment he told me this story, we talked of nothing else. I became deeply interested, and we ceaselessly discussed the probabilities of the case, and where she might be concealed. That she did not meditate suicide was evident from her having possessed herself of money; yet, unused to the world, young, lovely, and inexperienced, what could be her plan? What might not have been her fate?

“Meanwhile I continued for nearly three months confined by the fracture of my limb; before the lapse of that time, I had begun to crawl about the ground, and now I considered myself as nearly recovered. It had been settled that I should not return to Eton, but be entered at Oxford; and this leap from boyhood to man’s estate elated me considerably. Yet still I thought of my poor Ellen, and was angry at her obstinate silence. Once or twice I had, disobeying her command, written to her, mentioning my accident, and the kind attentions of Mr. Elmore. Still she wrote not; and I began to fear that her illness might have had a fatal termination. She had made me vow so solemnly never to mention her name, never to inquire about her during my absence, that, considering obedience the first duty of a young inexperienced boy to one older than himself, I resisted each suggestion of my affection or my fears to transgress her orders.

“And now spring came, with its gift of opening buds, odoriferous flowers, and sunny genial days. I returned home, and found my family on the eve of their departure for London; my long confinement had weakened me; it was deemed inadvisable for me to encounter the bad air and fatigues of the metropolis, and I remained to rusticate. I rode and hunted, and thought of Ellen; missing the excitement of her conversation, and feeling a vacancy in my heart which she had filled. I began to think of riding across the country from Shropshire to Berks for the purpose of seeing her. The whole landscape haunted my imagination—the fields round Eton—the silver Thames—the majestic forest—this lovely scene of Virginia Water—the heath and her desolate cottage—she herself pale, slightly bending from weakness of health, awakening from dark abstraction to bestow on me a kind smile of welcome. It grew into a passionate desire of my heart to behold her, to cheer her as I might by my affectionate attentions, to hear her, and to hang upon her accents of inconsolable despair as if it had been celestial harmony. As I meditated on these things, a voice seemed for ever to repeat, Now go, or it will be too late; while another yet more mournful tone responded, You can never see her more!

“I was occupied by these thoughts, as, on a summer moonlight night, I loitered in the shrubbery, unable to quit a scene of entrancing beauty, when I was startled at hearing myself called by Mr. Elmore. He came on his way to the coast; he had received a letter from Ireland, which made him think that Miss Eversham was residing near Enniscorthy,—a strange place for her to select, but as concealment was evidently her object, not an improbable one. Yet his hopes were not high; on the contrary, he performed this journey more from the resolve to leave nothing undone, than in expectation of a happy result. He asked me if I would accompany him; I was delighted with the offer, and we departed together on the following morning.

“We arrived at Milford Haven, where we were to take our passage. The packet was to sail early in the morning—we walked on the beach, and beguiled the time by talk. I had never mentioned Ellen to Lewis; I felt now strongly inclined to break my vow, and to relate my whole adventure with her; but restrained myself, and we spoke only of the unhappy Clarice—of the despair that must have been hers, of her remorse and unavailing regret.

“We retired to rest; and early in the morning I was called to prepare for going on board. I got ready, and then knocked at Lewis’ door; he admitted me, for he was dressed, though a few of his things were still unpacked, and scattered about the room. The morocco case of a miniature was on his table; I took it up. ‘Did I never show you that?’ said Elmore; ‘poor dear Clarice! she was very happy when that was painted!’

“I opened it;—rich, luxuriant curls clustered on her brow and the snow-white throat; there was a light zephyr appearance in the figure; an expression of unalloyed exuberant happiness in the countenance; but those large dove’s eyes, the innocence that dwelt on her mouth, could not be mistaken, and the name of Ellen Burnet burst from my lips.