Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The Wrong House

The Wrong House

by Katherine Mansfield

“Two purl—two plain—woolinfrontoftheneedle—and knit two together.” Like an old song, like a song that she had sung so often that only to breathe was to sing it, she murmured the knitting pattern. Another vest was nearly finished for the mission parcel.

“It’s your vests, Mrs. Bean, that are so acceptable. Look at these poor little mites without a shred!” And the churchwoman showed her a photograph of repulsive little black objects with bellies shaped like lemons…

“Two purl—two plain.” Down dropped the knitting on to her lap; she gave a great long sigh, stared in front of her for a moment and then picked the knitting up and began again. What did she think about when she sighed like that? Nothing. It was a habit. She was always sighing. On the stairs, particularly, as she went up and down, she stopped, holding her dress up with one hand, the other hand on the bannister, staring at the steps—sighing.

“Woolinfrontoftheneedle …” She sat at the dining-room window facing the street. It was a bitter autumn day; the wind ran in the street like a thin dog; the houses opposite looked as though they had been cut out with a pair of ugly steel scissors and pasted on to the grey paper sky. There was not a soul to be seen.

“Knit two together!” The clock struck three. Only three? It seemed dusk already; dusk came floating into the room, heavy, powdery dusk settling on the furniture, filming over the mirror. Now the kitchen clock struck three—two minutes late—for this was the clock to go by and not the kitchen clock. She was alone in the house. Dollicas was out shopping; she had been gone since a quarter to two. Really, she got slower and slower! What did she do with the time? One cannot spend more than a certain time buying a chicken … And oh, that habit of hers of dropping the stove-rings when she made up the fire! And she set her lips, as she had set her lips for the past thirty-five years, at that habit of Dollicas’.

There came a faint noise from the street, a noise of horses’ hooves. She leaned further out to see. Good gracious! It was a funeral. First the glass coach, rolling along briskly with the gleaming, varnished coffin inside (but no wreaths), with three men in front and two page 235 standing at the back, then some carriages, some with black horses, some with brown. The dust came bowling up the road, half hiding the procession. She scanned the houses opposite to see which had the blinds down. What horrible looking men, too! laughing and joking. One leaned over to one side and blew his nose with his black glove— horrible! She gathered up the knitting, hiding her hands in it. Dollicas surely would have known … There, they were passing … It was the other end …

What was this? What was happening? What could it mean? Help, God! Her old heart leaped like a fish and then fell as the glass coach drew up outside her door, as the outside men scrambled down from the front, swung off the back, and the tallest of them, with a glance of surprise at the windows, came quickly, stealthily, up the garden path.

“No!” she groaned. But yes, the blow fell, and for the moment it struck her down. She gasped, a great cold shiver went through her, and stayed in her hands and knees. She saw the man withdraw a step and again—that puzzled glance at the blinds—then—

“No!” she groaned, and stumbling, catching hold of things, she managed to get to the door before the blow fell again. She opened it, her chin trembled, her teeth clacked; somehow or other she brought out, “The wrong house!”

Oh! he was shocked. As she stepped back she saw behind him the black hats clustered at the gate. “The wrong’ ouse!” he muttered. She could only nod. She was shutting the door again when he fished out of the tail of his coat a black, brass-bound notebook and swiftly opened it. “No. 20 Shuttleworth Crescent?”

“S—street! Crescent round the corner.” Her hand lifted to point, but shook and fell.

He was taking off his hat as she shut the door and leaned against it, whimpering in the dusky hall, “Go away! Go away!”

Clockety-clock-clock. Cluk! Cluk! Clockety-clock-cluk! sounded from outside, and then a faint Cluk! Cluk! and then silence. They were gone. They were out of sight. But still she stayed leaning against the door, staring into the hall, staring at the hall-stand that was like a great lobster with hat-pegs for feelers. But she thought of nothing; she did not even think of what had happened. It was as if she had fallen into a cave whose walls were darkness …

She came to herself with a deep inward shock, hearing the gate bang and quick, short steps crunching the gravel; it was Dollicas hurrying round to the back door. Dollicas must not find her there; and wavering, wavering like a candle-flame, back she went into the dining-room to her seat by the window.

Dollicas was in the kitchen. Klang! went one of the iron rings into the fender. Then her voice, “I’m just putting on the teakettle’m.” Since they had been alone she had got into the way of shouting from one room to another. The old woman coughed to steady herself. “Please bring in the lamp,” she cried.

“The lamp!” Dollicas came across the passage and stood in the doorway. “Why, it’s only just on four’ m.”

“Never mind,” said Mrs. Bean dully.

“Bring it in!” And a moment later the elderly maid appeared, carrying the gentle lamp in both hands. Her broad soft face had the look it always had when she carried anything, as though she walked in her sleep. She set it down on the table, lowered the wick, raised it, and then lowered it again. Then she straightened up and looked across at her mistress.

“Why, ‘m, whatever’s that you’re treading on?”

It was the mission vest.

“T’t! T’t!” As Dollicas picked it up she thought, “The old lady has been asleep. She’s not awake yet.” Indeed the old lady looked glazed and dazed, and when she took up the knitting she drew out a needle of stitches and began to unwind what she had done.

“Don’t forget the mace,” she said. Her voice sounded thin and dry. She was thinking of the chicken for that night’s supper. And Dollicas understood and answered, “It’s a lovely young bird!”‘as she pulled down the blind before going back to her kitchen …

The Wrong House (1919)

by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923)

From: Something Childish and Other Stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Katherine Mansfield, Mansfield, Katherine

Karoline von Günderrode

(1780 – 1806)

Der Gefangene und der Sänger

Ich wallte mit leichtem und lustigem Sinn

Und singend am Kerker vorüber;

Da schallt aus der Tiefe, da schallt aus dem Thurm

Mir Stimme des Freundes herüber. –

„Ach Sänger! verweile, mich tröstet dein Lied,

Es steigt zum Gefangnen herunter,

Ihm macht es gesellig die einsame Zeit,

Das krankende Herz ihm gesunder.“

Ich horchte der Stimme, gehorchte ihr bald,

Zum Kerker hin wandt’ ich die Schritte,

Gern sprach ich die freundlichsten Worte hinab,

Begegnete jeglicher Bitte.

Da war dem Gefangenen freier der Sinn,

Gesellig die einsamen Stunden. –

„Gern gäb ich dir Lieber! so rief er: die Hand,

Doch ist sie von Banden umwunden.

Gern käm’ ich Geliebter! gern käm’ ich herauf

Am Herzen dich treulich zu herzen;

Doch trennen mich Mauern und Riegel von dir,

O fühl’ des Gefangenen Schmerzen.

Es ziehet mich mancherlei Sehnsucht zu dir;

Doch Ketten umfangen mein Leben,

Drum gehe mein Lieber und laß mich allein,

Ich Armer ich kann dir nichts geben.“ –

Da ward mir so weich und so wehe ums Herz,

Ich konnte den Lieben nicht lassen.

Am Kerker nun lausch’ ich von Frührothes Schein

Bis Abends die Farben erblassen.

Und harren dort werd’ ich die Jahre hindurch,

Und sollt’ ich drob selber erblassen.

Es ist mir so weich und so sehnend ums Herz

Ich kann den Geliebten nicht lassen.

Karoline Günderrode Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Karoline von Günderrode

Poison

Poison

by Katherine Mansfield

The post was very late. When we came back from our walk after lunch it still had not arrived.

“Pas encore, Madame,” sang Annette, scurrying back to her cooking.

We carried our parcels into the dining-room. The table was laid. As always, the sight of the table laid for two—for two people only—and yet so finished, so perfect, there was no possible room for a third, gave me a queer, quick thrill as though I’d been struck by that silver lightning that quivered over the white cloth, the brilliant glasses, the shallow bowl of freezias.

“Blow the old postman! Whatever can have happened to him?” said Beatrice. “Put those things down, dearest.”

“Where would you like them …?”

She raised her head; she smiled her sweet, teasing smile.

“Anywhere—Silly.”

But I knew only too well that there was no such place for her, and I would have stood holding the squat liqueur bottle and the sweets for months, for years, rather than risk giving another tiny shock to her exquisite sense of order.

“Here—I’ll take them.” She plumped them down on the table with her long gloves and a basket of figs. “The Luncheon Table. Short story by—by—” She took my arm. “Let’s go on to the terrace—” and I felt her shiver. “Ça sent,” she said faintly, “de la cuisine …”

I had noticed lately—we had been living in the south for two months—that when she wished to speak of food, or the climate, or, playfully, of her love for me, she always dropped into French.

We perched on the balustrade under the awning. Beatrice leaned over gazing down—down to the white road with its guard of cactus spears. The beauty of her ear, just her ear, the marvel of it was so great that I could have turned from regarding it to all that sweep of glittering sea below and stammered: “You know—her ear! She has ears that are simply the most …”

She was dressed in white, with pearls round her throat and lilies-of-the-valley tucked into her belt. On the third finger of her left hand she wore one pearl ring—no wedding ring.

“Why should I, mon ami? Why should we pretend? Who could possibly care?”

And of course I agreed, though privately, in the depths of my heart, I would have given my soul to have stood beside her in a large, yes, a large, fashionable church, crammed with people, with old reverend clergymen, with The Voice that breathed o’er Eden, with palms and the smell of scent, knowing there was a red carpet and confetti outside, and somewhere, a wedding-cake and champagne and a satin shoe to throw after the carriage—if I could have slipped our wedding-ring on to her finger.

Not because I cared for such horrible shows, but because I felt it might possibly perhaps lessen this ghastly feeling of absolute freedom, her absolute freedom, of course.

Oh, God! What torture happiness was—what anguish! I looked up at the villa, at the windows of our room hidden so mysteriously behind the green straw blinds. Was it possible that she ever came moving through the green light and smiling that secret smile, that languid, brilliant smile that was just for me? She put her arm round my neck; the other hand softly, terribly, brushed back my hair.

“Who are you?” Who was she? She was—Woman.

… On the first warm evening in Spring, when lights shone like pearls through the lilac air and voices murmured in the fresh-flowering gardens, it was she who sang in the tall house with the tulle curtains. As one drove in the moonlight through the foreign city hers was the shadow that fell across the quivering gold of the shutters. When the lamp was lighted, in the new-born stillness her steps passed your door. And she looked out into the autumn twilight, pale in her furs, as the automobile swept by …

In fact, to put it shortly, I was twenty-four at the time. And when she lay on her back, with the pearls slipped under her chin, and sighed “I’m thirsty, dearest. Donne-moi un orange,” I would gladly, willingly, have dived for an orange into the jaws of a crocodile—if crocodiles ate oranges.

“Had I two little feathery wings

And were a little feathery bird …”

sang Beatrice.

I seized her hand. “You wouldn’t fly away?”

“Not far. Not further than the bottom of the road.”

“Why on earth there?”

She quoted: “He cometh not, she said …”

“Who? The silly old postman? But you’re not expecting a letter.”

“No, but it’s maddening all the same. Ah!” Suddenly she laughed and leaned against me. “There he is—look—like a blue beetle.”

And we pressed our cheeks together and watched the blue beetle beginning to climb.

“Dearest,” breathed Beatrice. And the word seemed to linger in the air, to throb in the air like the note of a violin.

“What is it?”

“I don’t know,” she laughed softly. “A wave of—a wave of affection, I suppose.”

I put my arm round her. “Then you wouldn’t fly away?”

And she said rapidly and softly: “No! No! Not for worlds. Not really. I love this place. I’ve loved being here. I could stay here for years, I believe. I’ve never been so happy as I have these last two months, and you’ve been so perfect to me, dearest, in every way.”

This was such bliss—it was so extraordinary, so unprecedented, to hear her talk like this that I had to try to laugh it off.

“Don’t! You sound as if you were saying good-bye.”

“Oh, nonsense, nonsense. You mustn’t say such things even in fun!” She slid her little hand under my white jacket and clutched my shoulder. “You’ve been happy, haven’t you?”

“Happy? Happy? Oh, God—if you knew what I feel at this moment … Happy! My Wonder! My Joy!”

I dropped off the balustrade and embraced her, lifting her in my arms. And while I held her lifted I pressed my face in her breast and muttered: “You are mine?” And for the first time in all the desperate months I’d known her, even counting the last month of— surely—Heaven—I believed her absolutely when she answered:

“Yes, I am yours.”

The creak of the gate and the postman’s steps on the gravel drew us apart. I was dizzy for the moment. I simply stood there, smiling, I felt, rather stupidly. Beatrice walked over to the cane chairs.

“You go—go for the letters,” said she.

I—well—I almost reeled away. But I was too late. Annette came running. “Pas de lettres” said she.

My reckless smile in reply as she handed me the paper must have surprised her. I was wild with joy. I threw the paper up into the air and sang out:

“No letters, darling!” as I came over to where the beloved woman was lying in the long chair.

For a moment she did not reply. Then she said slowly as she tore off the newspaper wrapper: “The world forgetting, by the world forgot.”

There are times when a cigarette is just the very one thing that will carry you over the moment. It is more than a confederate, even; it is a secret, perfect little friend who knows all about it and understands absolutely. While you smoke you look down at it—smile or frown, as the occasion demands; you inhale deeply and expel the smoke in a slow fan. This was one of those moments. I walked over to the magnolia and breathed my fill of it. Then I came back and leaned over her shoulder. But quickly she tossed the paper away on to the stone.

“There’s nothing in it,” said she. “Nothing. There’s only some poison trial. Either some man did or didn’t murder his wife, and twenty thousand people have sat in court every day and two million words have been wired all over the world after each proceeding.”

“Silly world!” said I, flinging into another chair. I wanted to forget the paper, to return, but cautiously, of course, to that moment before the postman came. But when she answered I knew from her voice the moment was over for now. Never mind. I was content to wait—five hundred years, if need be—now that I knew.

“Not so very silly,” said Beatrice. “After all it isn’t only morbid curiosity on the part of the twenty thousand.”

“What is it, darling?” Heavens knows I didn’t care.

“Guilt! “she cried. “Guilt! Didn’t you realise that? They’re fascinated like sick people are fascinated by anything—any scrap of news about their own case. The man in the dock may be innocent enough, but the people in court are nearly all of them poisoners. Haven’t you ever thought” —she was pale with excitement— “of the amount of poisoning that goes on? It’s the exception to find married people who don’t poison each other— married people and lovers. Oh,” she cried, “the number of cups of tea, glasses of wine, cups of coffee that are just tainted. The number I’ve had myself, and drunk, either knowing or not knowing—and risked it. The only reason why so many couples”—she laughed—” survive, is because the one is frightened of giving the other the fatal dose. That dose takes nerve! But it’s bound to come sooner or later. There’s no going back once the first little dose has been given. It’s the beginning of the end, really—don’t you agree? Don’t you see what I mean?”

She didn’t wait for me to answer. She unpinned the lilies-of-the-valley and lay back, drawing them across her eyes.

“Both my husbands poisoned me,” said Beatrice. “My first husband gave me a huge dose almost immediately, but my second was really an artist in his way. Just a tiny pinch, now and again, cleverly disguised—Oh, so cleverly! —until one morning I woke up and in every single particle of me, to the ends of my fingers and toes, there was a tiny grain. I was just in time …”

I hated to hear her mention her husbands so calmly, especially to-day. It hurt. I was going to speak, but suddenly she cried mournfully:

“Why! Why should it have happened to me? What have I done? Why have I been all my life singled out by … It’s a conspiracy.”

I tried to tell her it was because she was too perfect for this horrible world—too exquisite, too fine. It frightened people. I made a little joke.

“But I—I haven’t tried to poison you.”

Beatrice gave a queer small laugh and bit the end of a lily stem.

“You!” said she. “You wouldn’t hurt a fly!”

Strange. That hurt, though. Most horribly.

Just then Annette ran out with our apéritifs. Beatrice leaned forward and took a glass from the tray and handed it to me. I noticed the gleam of the pearl on what I called her pearl finger. How could I be hurt at what she said?

“And you,” I said, taking the glass, “you’ve never poisoned anybody.”

That gave me an idea; I tried to explain.

“You—you do just the opposite. What is the name for one like you who, instead of poisoning people, fills them—everybody, the postman, the man who drives us, our boatman, the flower-seller, me—with new life, with something of her own radiance, her beauty, her—”

Dreamily she smiled; dreamily she looked at me.

“What are you thinking of—my lovely darling?”

“I was wondering,” she said, “whether, after lunch, you’d go down to the post-office and ask for the afternoon letters. Would you mind, dearest? Not that I’m expecting one —but—I just thought, perhaps—it’s silly not to have the letters if they’re there. Isn’t it? Silly to wait till to-morrow.” She twirled the stem of the glass in her fingers. Her beautiful head was bent. But I lifted my glass and drank, sipped rather—sipped slowly, deliberately, looking at that dark head and thinking of—postmen and blue beetles and farewells that were not farewells and …

Good God! Was it fancy? No, it wasn’t fancy. The drink tasted chill, bitter, queer.

Poison

by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923)

From: Something Childish and Other Stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Katherine Mansfield, Mansfield, Katherine

Sibylla Schwarz

(1621 – 1638)

Cloris

Cloris

deine rohte Wangen

deiner Augen helles Licht

und dein Purpurangesicht

hält mich nuhn nicht mehr gefangen.

Ich kan nicht mehr an dir hangen

weil du dich erbarmest nicht

ob mir schon mein Hertze bricht;

deiner schnöden Hoffart Prangen

und dein hönisches Gemüht

krencket mir mein jung Geblüht

daß ich dich wil gerne meiden

wan mich meine Galate

die mir macht dis süße Weh

wil in ihren Diensten leiden.

Sibylla Schwarz poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, SIbylla Schwarz

Sibylla Schwarz

(1621 – 1638)

Poëten gehn

dem unadelichen Adel

weit vohr

Ob zwar mein schlechter Leib

zu deme sich muß halten

was schlecht und niedrig ist

und lassen alles walten

was reiche Güter hat

was grossen Titul führet

was Weißheit

Kunst und Lob mit

blassem Ansehn zieret.

So bleibt dennoch mein Sinn

allzeit am Himmel kleben

da ein Poëte kan

ohn Schimpff und Schaden leben

da niemand sagen kan: Sih

diser geht dich für!

da keine Leumder sein

da bloß des Himmels Zier

mit ihnen Sprache helt

da alles muß erbleichen

da ein vom Adel muß

dem schlechsten Diener weichen.

Und wenn ein hoher Heldt

bey seinem Degen geht

der sehe sich wohl für

daß er ja feste steht;

denn wer

auß Hoffahrt nur

den Degen angehencket

dem wird gemeinlich auch

der Schwerdter Schmach geschenket

und wenn die Hoffart denn

wird endlich untergehn

wird der Poëten Volck

doch immer oben stehn.

Sibylla Schwarz poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, SIbylla Schwarz

Spring Pictures

Spring Pictures

by Katherine Mansfield

I

It is raining. Big soft drops splash on the people’s hands and cheeks; immense warm drops like melted stars. “Here are roses! Here are lilies! Here are violets!” caws the old hag in the gutter. But the lilies, bunched together in a frill of green, look more like faded cauliflowers. Up and down she drags the creaking barrow. A bad, sickly smell comes from it. Nobody wants to buy. You must walk in the middle of the road, for there is no room on the pavement. Every single shop brims over; every shop shows a tattered frill of soiled lace and dirty ribbon to charm and entice you. There are tables set out with toy cannons and soldiers and Zeppelins and photograph frames complete with ogling beauties. There are immense baskets of yellow straw hats piled up like pyramids of pastry, and strings of coloured boots and shoes so small that nobody could wear them. One shop is full of little squares of mackintosh, page 185 blue ones for girls and pink ones for boys with Bébé printed in the middle of each …

“Here are lilies! Here are roses! Here are pretty violets!” warbles the old hag, bumping into another barrow. But this barrow is still. It is heaped with lettuces. Its owner, a fat old woman, sprawls across, fast asleep, her nose in the lettuce roots … Who is ever going to buy anything here …? The sellers are women. They sit on little canvas stools, dreamy and vacant looking. Now and again one of them gets up and takes a feather duster, like a smoky torch, and flicks it over a thing or two and then sits down again. Even the old man in tangerine spectacles with a balloon of a belly, who turns the revolving stand of ‘comic’ postcards round and round cannot decide …

Suddenly, from the empty shop at the corner a piano strikes up, and a violin and flute join in. The windows of the shop are scrawled over—New Songs. First Floor. Entrance Free. But the windows of the first floor being open, nobody bothers to go up. They hang about grinning as the harsh voices float out into the warm rainy air. At the doorway there stands a lean man in a pair of burst carpet slippers. He has stuck a feather through the broken rim of his hat; with what an air he wears it! The feather is magnificent. It is gold epaulettes, frogged coat, page 186 white kid gloves, gilded cane. He swaggers under it and the voice rolls off his chest, rich and ample.

“Come up! Come up! Here are the new songs! Each singer is an artiste of European reputation. The orchestra is famous and second to none. You can stay as long as you like. It is the chance of a lifetime, and once missed never to return!” But nobody moves. Why should they? They know all about those girls—those famous artistes. One is dressed in cream cashmere and one in blue. Both have dark crimped hair and a pink rose pinned over the ear … They know all about the pianist’s button boots—the left foot—the pedal foot—burst over the bunion on his big toe. The violinist’s bitten nails, the long, far too long cuffs of the flute player—all these things are as old as the new songs.

For a long time the music goes on and the proud voice thunders. Then somebody calls down the stairs and the showman, still with his grand air, disappears. The voices cease. The piano, the violin and the flute dribble into quiet. Only the lace curtain gives a wavy sign of life from the first floor.

It is raining still; it is getting dusky … Here are roses! Here are lilies! Who will buy my violets? …

II

Hope! You misery—you sentimental, faded female! Break your last string and have done with it. I shall go mad with your endless thrumming; my heart throbs to it and every little pulse beats in time. It is morning. I lie in the empty bed—the huge bed big as a field and as cold and unsheltered. Through the shutters the sunlight comes up from the river and flows over the ceiling in trembling waves. I hear from outside a hammer tapping, and far below in the house a door swings open and shuts. Is this my room? Are those my clothes folded over an armchair? Under the pillow, sign and symbol of a lonely woman, ticks my watch. The bell jangles. Ah! At last! I leap out of bed and run to the door. Play faster—faster—Hope!

“Your milk, Mademoiselle,” says the concierge, gazing at me severely.

“Ah, thank you,” I cry, gaily swinging the milk bottle. “No letters for me?”

“Nothing, mademoiselle.”

“But the postman—he has called already?”

“A long half-hour ago, mademoiselle.”

Shut the door. Stand in the little passage a moment. Listen—listen for her hated twanging. Coax her—court her—implore her to play just once that charming little thing for one string only. In vain.

III

Across the river, on the narrow stone path that fringes the bank, a woman is walking. She came down the steps from the Quay, walking slowly, one hand on her hip. It is a beautiful evening; the sky is the colour of lilac and the river of violet leaves. There are big bright trees along the path full of trembling light, and the boats, dancing up and down, send heavy curls of foam rippling almost to her feet. Now she has stopped. Now she has turned suddenly. She is leaning up against a tree, her hands over her face; she is crying. And now she is walking up and down wringing her hands. Again she leans against the tree, her back against it, her head raised and her hands clasped as though she leaned against someone dear. Round her shoulders she wears a little grey shawl; she covers her face with the ends of it and rocks to and fro.

But one cannot cry for ever, so at last she becomes serious and quiet, patting her hair into place, smoothing her apron. She walks a step or two. No, too soon, too soon! Again her arms fly up—she runs back—again she is blotted against the tall tree. Squares of gold light show in the houses; the street lamps gleam through the new leaves; yellow fans of light follow the dancing boats. For a moment she is a blur against the tree, white, grey and black, melting into the stones and the shadows. And then she is gone.

Spring Pictures (1915)

by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923)

From: Something Childish and Other Stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Spring, Archive M-N, Katherine Mansfield, Mansfield, Katherine

Sibylla Schwarz

(1621 – 1638)

Die Lieb ist Blind

Die Lieb ist blind

und gleichwohl kan sie sehen

hat ein Gesicht

und ist doch stahrenblind

sie nennt sich groß

und ist ein kleines Kind

ist wohl zu Fuß

und kan dannoch nicht gehen.

Doch diss muß man auff ander’ art verstehen:

sie kan nicht sehn

weil ihr Verstand zerrint

und weil das Aug des Herzens ihr verschwindt

so siht sie selbst nicht

was ihr ist geschehen.

Das

was sie liebt

hat keinen Mangel nicht

wie wohl ihm mehr

als andern

offt gebricht.

Das

was sie liebt

kan ohn Gebrechen leben;

doch weil man hier ohn Fehler nichtes find

so schließ ich fort: Die Lieb ist sehend blind:

sie siht selbst nicht

und kans Gesichte geben.

Sibylla Schwarz poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, SIbylla Schwarz

Sibylla Schwarz

(1621 – 1638)

Wer kan jederman gefallen?

Ob schon des Höchsten Hand

die ganze Welt versehen

daß nicht es drinn gebricht

doch sol noch in der Welt

gebohren werden der

der allen wohl gefält

und eh der lebend wird

wird wohl die Welt vergehen.

Sibylla Schwarz poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, SIbylla Schwarz

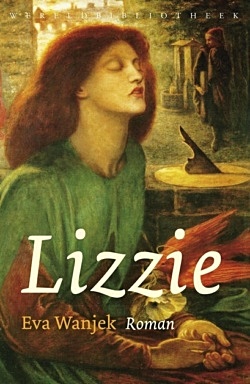

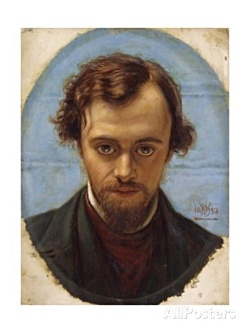

De kunstenaar en zijn muze: liefde, begeerte, desillusie en onontkoombare verbondenheid

Een onconventionele relatie tussen twee bijzondere mensen leidt hen naar de toppen van de roem, maar ook naar afgronden van ellende en vertwijfeling: van drank, opium en vooral wederzijdse afhankelijkheid. Het is de symbiotische relatie van een gedreven kunstenaar die alles – ook zijn eigen geluk en dat van anderen – opoffert voor de kunst, en een vrouw die haar bestaansrecht ontleent aan haar uitzonderlijke schoonheid, terwijl ze faalt in haar eigen artistieke ambities.

Een onconventionele relatie tussen twee bijzondere mensen leidt hen naar de toppen van de roem, maar ook naar afgronden van ellende en vertwijfeling: van drank, opium en vooral wederzijdse afhankelijkheid. Het is de symbiotische relatie van een gedreven kunstenaar die alles – ook zijn eigen geluk en dat van anderen – opoffert voor de kunst, en een vrouw die haar bestaansrecht ontleent aan haar uitzonderlijke schoonheid, terwijl ze faalt in haar eigen artistieke ambities.

Lizzie geeft een levendig en panoramisch beeld van het bruisende Londen van de 19de eeuw, met zijn culturele elite, zijn bohémiens en zijn zelfkant. Hij biedt zowel kostuumdrama en ‘Gothic horror’ als erotische en indringende psychologische scènes. Het is een groots opgezet drama, van de allereerste ontmoeting in 1849 tussen het onbekende naaistertje en het aanstormende genie, tot aan diens dood als beroemde, maar eenzame weduwnaar in 1882.

Lizzie is een boeiende roman, die alle facetten van een man-vrouwrelatie toont, van prille liefde en begeerte, via wederzijdse ontrouw, vervreemding en desillusie tot aan het besef van absolute lotsverbondenheid.

Eva Wanjek is het pseudoniem waaronder twee auteurs van Uitgeverij Wereldbibliotheek hun krachten hebben gebundeld: de romanschrijver Martin Michael Driessen en de dichteres Liesbeth Lagemaat.

De pers over Lizzie:

‘Een samenwerkingsverband tussen Martin Michael Driessen en Liesbeth Lagemaat leidt tot een historische roman waarin kunstzinnige verhevenheid en de liefde het pijnlijk afleggen tegen de zelfdestructie. ****’ NRC Handelsblad

‘De auteurs hebben dit tranentrekkende, vuistdikke verhaal schittering opgebouwd. beelden trekken als een film aan je voorbij en laten je niet los. En al ben je broodnuchter, raak je door hun liefdesgeschiedenis die gedoemd is te mislukken, bedwelmd, en leest die in één gelukzalige roes uit.’ Baarnsche Courant

Een fragment uit: ‘Lizzie’

En als Miss Siddall maar lang genoeg in dit water ligt terwijl ik schilder, en vergeet waar ze is, dan krijg ik misschien juist de uitdrukking die ik zoek. Die van vergetelheid, van opgave, alsof ze op de wateren van de Lethe drijft. Misschien helpt een beetje laudanum. En ze is mooi genoeg om ook dan nog begeerlijk te zijn. Want dat is waarom het gaat. Ophelia moet in haar dood begeerlijk zijn. Want alleen dan is het tragisch dat niemand haar ooit zal beminnen.

En als Miss Siddall maar lang genoeg in dit water ligt terwijl ik schilder, en vergeet waar ze is, dan krijg ik misschien juist de uitdrukking die ik zoek. Die van vergetelheid, van opgave, alsof ze op de wateren van de Lethe drijft. Misschien helpt een beetje laudanum. En ze is mooi genoeg om ook dan nog begeerlijk te zijn. Want dat is waarom het gaat. Ophelia moet in haar dood begeerlijk zijn. Want alleen dan is het tragisch dat niemand haar ooit zal beminnen.

Hij vroeg zich af wie van hen Miss Siddall als eerste bezitten zou. Ik niet, dacht hij, ze is zo kwetsbaar, daar zit je voor de rest van je leven aan vast. Hunt was te rechtschapen, die zou alleen met zijn wettige echtgenote naar bed gaan. En Deverell ook niet. Walter was idolaat van haar, maar hij was een ziek man. Het zou Dante wel zijn. Lizzie was Dante’s meisje.

Nog een fragment uit: ‘Lizzie’

Ik ben Rossetti,’ zegt hij en ik hoor zijn stem vertraagd, alsof hij weerkaatst wordt door een gewelf. ‘Mijn naam is Dante Gabriel Rossetti, u zult wel nooit van mij gehoord hebben. Ik ben dichter en schilder.

Ik ben Rossetti,’ zegt hij en ik hoor zijn stem vertraagd, alsof hij weerkaatst wordt door een gewelf. ‘Mijn naam is Dante Gabriel Rossetti, u zult wel nooit van mij gehoord hebben. Ik ben dichter en schilder.

Er is een beweging, de Prerafaëlitische Broederschap… zo noemen we ons… waarvan ik de leider ben. En nu ik u heb gezien, wil ik u vragen…’

Als een mens ooit werd opgetild van de aarde, dan werd ik het, nu. Ik wist niet wat me overkwam. Maar ik wist wel wat ik nu wilde zeggen…

Ze glimlachte en reciteerde – bevangen, als iemand die onwennig op een bruiloft of uitvaart spreekt en bang is iets verkeerds te zeggen – twee van zijn eigen verzen, uit ‘The Blessed Damozel’:

I’ll take his hand and go with him

To the deep wells of light…

Hij knielde voor haar en kuste haar hand. Het was voor het eerst in haar leven dat een man voor haar knielde. Nu mocht en kon er niets meer gezegd worden.

In de deuropening draaide hij zich om. Ze zat nog steeds op haar stoel, haar ene hand op het tafelblad, blank en haast doorschijnend, als door een Hollandse meester geschilderd. Ze keek over haar schouder naar het beroete raam, dat nauwelijks licht doorliet, en scheen weer onbereikbaar, in haar eigen gedachten verzonken. Was ze zo, of poseerde ze? Wat het ook was, ze deed het goed.

Voordat Dante de deur weer sloot, maakte hij met zachte stem de strofe af:

As unto a stream we will step down,

And bathe there in God’s sight

Eva Wanjek:

Eva Wanjek:

Lizzie

paperback met flappen

15×23 cm.

464 pagina’s

ISBN 9789028426160

prijs € 24,95

Uitgeverij Wereldbibliotheek

Johannes Vermeerstraat 63, 1071 DN Amsterdam

Tel: 020 570 61 00

Fax: 020 570 61 99

E-mail: info@wereldbibliotheek.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *The Pre-Raphaelites Archive, - Book News, Archive W-X, Lizzy Siddal, Rossetti, Dante Gabriel, Siddal, Lizzy

Ingrid Jonker – André Brink

Ingrid Jonker – André Brink

Vlam in de sneeuw

Van de jonggestorven, iconische dichter Ingrid Jonker is bekend dat ze mannen het hoofd op hol wist te brengen. Een van hen was de onlangs gestorven schrijver André Brink. Tot kort voor Ingrids zelfgekozen dood, op haar eenendertigste, was hij haar vurige minnaar. Op geografische afstand, wat voor de literatuurgeschiedenis nu een zegen blijkt. Want het noodde hen tot een jarenlange, ongekend intense liefdescorrespondentie. Vlam in de sneeuw biedt allereerst een intieme blik op de jonge levens van twee veelbelovende schrijvers die, nog zoekende naar hun plek in de wereld, tot over hun oren verliefd op elkaar worden. Maar ze delen niet alleen hun liefde voor elkaar, ook delen ze hun twijfels over hun schrijverschap en hun diepste overtuigingen over geloof, literatuur en politiek. Het is met grote trots dat wij deze tot vurige woorden gestolde passie, kort na verschijning in Zuid-Afrika, nu voor de Nederlandse lezer mogen ontsluiten.

512 pagina’s

omslag: Studio Ron van Roon

ISBN: 978 90 5759 775 6

Nur: 320

originele titel: Vlam in die sneeu

vertaler: Karina van Santen, Rob van der Veer en Martine Vosmaer

€ 34,90

uitgeverij Podium

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Archive S.A. literature, - Book News, André Brink, Archive A-B, Archive I-J, Ingrid Jonker, Ingrid Jonker

Amy Winehouse: A Family Portrait

Amy Winehouse: A Family Portrait

Tentoonstelling van 29 februari tot en met 4 september 2016

Amy Winehouse, een van de meest succesvolle artiesten van de afgelopen decennia, staat van 29 februari tot en met 4 september 2016 centraal in het Joods Historisch Museum. Amy Winehouse: A Family Portrait is een persoonlijke en intieme tentoonstelling, samengesteld door Amy’s broer Alex Winehouse en The Jewish Museum in Londen. Eerder trok deze expositie in Londen, Tel Aviv, Wenen en San Francisco veel bezoekers.

In de tentoonstelling ligt de nadruk op Amy’s passie voor muziek en mode, maar ook op haar joodse familiegeschiedenis en haar schooltijd. Verder is er aandacht voor Londen, in het bijzonder Camden Town, waar Amy lange tijd woonde. De bezoeker krijgt een nog onbekende kant van Amy te zien: als tiener en jonge vrouw die nog niet is beïnvloed door de enorme media-aandacht en sensatiezucht die haar later fataal werden.

De familie Winehouse stelde voor de tentoonstelling veel van Amy’s persoonlijke bezittingen ter beschikking die, dankzij de begeleidende teksten van Alex, nog intiemer worden: foto’s van haar jeugd, een videoclip van een schooloptreden, haar tapschoenen en lievelingsgitaar, haar platencollectie en verschillende tijdens concerten gedragen jurken. Op de tentoonstelling hangen ook fotoportretten van Amy en is de Grammy Award te zien, die haar na haar overlijden in 2011 werd toegekend.

Amy Winehouse: A Family Portrait neemt de bezoeker mee voorbij de hype en laat Amy zien zoals ze als privépersoon was. Alex Winehouse zei over zijn zus: ‘Amy was iemand die ongelofelijk trots was op haar Londense joodse roots. We waren niet gelovig, maar wel traditioneel. Ik hoop dat de wereld deze andere kant van Amy leert kennen, die van onze typische joodse familie.’

Het evenementenprogramma bij de tentoonstelling bevat onder meer een opstelwedstrijd voor scholieren (gebaseerd op een opstel van Amy dat in de tentoonstelling te zien is), de recreatie van een klein deel van de hippe Londense wijk Camden market en de vertoning van de BBC-documentaire Amy Winehouse: The Day She Came to Dingle uit 2006.

De gelijknamige Engelstalige geïllustreerde catalogus zal verkrijgbaar zijn in de Museumshop van het Joods Historisch Museum.

# Meer info op website Joods Historisch Museum Amsterdam

Amy Winehouse: A Family Portrait

Joods Historisch Museum

Nieuwe Amstelstraat 1, 1011 PL Amsterdam

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Amy Winehouse, Amy Winehouse, Art & Literature News

Laure

(Colette Peignot 1903 – 1938))

D’où viens-tu ?

D’où viens-tu avec ton cœur

déchiré aux ronces du chemin.

Les mains calleuses de casseur de pierre

et ta tête gonflée comme une

outre piquée ?

Nous sommes ceux qui crient dans le désert

qui hurlent à la lune.

Je le sens bien maintenant : « mon devoir m’est remis. » Mais

lequel exactement ?

C’est parfois si lourd et si dur que je voudrais courir dans la

Campagne.

Nager dans la rivière

oublier tout ce qui fut, oublier l’enfance sordide et timorée.

Le vendredi saint, le mercredi des cendres.

l’enfance toute endeuillée à odeur de crêpe et de naphtaline

L’adolescence hâve et tourmentée.

Les mains d’anémiée.

Oublier le sublime et l’infâme

Les gestes hiératiques

Les grimaces démoniaques.

Oublier

Tout élan falsifié

Tout espoir étouffé

Ce goût de cendre

Oublier qu’à vouloir tout

on ne peut rien

Vivre enfin

« Ni tourmentante

Ni tourmentée »

Remonter le cours des fleuves

Retrouver les sources des montagnes

les femmes les vrais hommes travailleurs

qui enfantent

moissonnant

M’étendre dans les prairies

Quitter ce climat

Ses dunes, ses landes sablonneuses, cette grisaille et

ses déserts artificiels,

Ce désespoir dont on fait vertu,

Ce désespoir qui se boit

se sirote à la terrasse des cafés

s’édite… et ne demanderait qu’à nourrir très bien son homme

Vivre enfin

Sans s’accuser

ni se justifier

Victime

ou coupable

comment dire ?

Un tremblement de terre m’a dévastée

On t’a mordu l’âme

Enfant !

Et ces cris et ces plaintes

Et cette faiblesse native

Oui –

Et s’ils ont vu mes larmes

Que ma tête s’enfonce

jusqu’à toucher

le bois

et la terre

LAURE (Colette Peignot) poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive K-L, Laure (Colette Peignot)

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature