Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

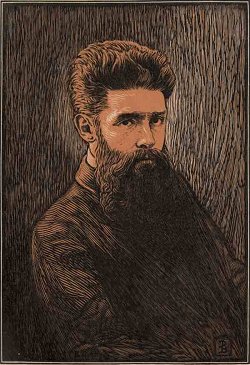

August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

(1798-1874)

Morgenlied

Die Sterne sind erblichen

Mit ihrem güldnen Schein.

Bald ist die Nacht entwichen,

Der Morgen dringt herein.

Noch waltet tiefes Schweigen

Im Thal und überall;

Auf frischbethauten Zweigen

Singt nur die Nachtigall.

Sie singet Lob und Ehre

Dem hohen Herrn der Welt,

Der überm Land und Meere

Die Hand des Segens hält.

Er hat die Nacht vertrieben:

Ihr Kindlein, fürchtet nichts!

Stets kommt zu seinen Lieben

Der Vater alles Lichts.

August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Archive G-H, CLASSIC POETRY

Luise Hensel

(1798-1876)

Zug der Liebe

Ach! vergessen könnt’ ich nimmer

Seiner Liebe, Seiner Pein.

Sein gedenken will ich immer;

Garten, Feld und Wald und Zimmer

Soll mir stets ein Bethaus sein.

Stündlich will ich Ihn begrüßen:

»Sei gepriesen, süßer Freund!«

Alle Blumen, die da sprießen,

Will ich mit dem Thau begießen,

Den um Ihn mein Auge weint. –

Keine Gaben, keine Freuden,

Keine Krone dieser Welt!

Freudig will ich Alles meiden,

Will nur Er von mir nicht scheiden,

Den mein Herz so innig hält.

Wer ein Tröpflein durfte trinken,

Herr! aus Deinem Gnadenmeer,

Der muß ganz darin versinken,

Folgen einzig Deinen Winken

Ohne Sinne, ohn’ Gehör.

Und ich kann Dich nimmer lassen,

Ewig halt’ ich Dich umarmt.

Wolltest Du mich fliehn und hassen,

Müßt’ ich noch Dein Kreuz umfassen,

Bis es jeden Stein erbarmt.

Wärst Du nicht im Himmel drinnen,

Nimmer sehnt’ ich mich hinein. –

All mein Wissen, all mein Sinnen,

Herr! laß ganz in Dich verrinnen,

Ganz in Dir verloren sein.

Münster, Sommer 1819.

Luise Hensel poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, CLASSIC POETRY

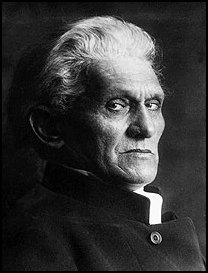

Heinrich Heine

(1797-1856)

An einen politischen Dichter

Du singst, wie einst Tyrtäus sang,

Von Heldenmut beseelet,

Doch hast du schlecht dein Publikum

Und deine Zeit gewählet.

Beifällig horchen sie dir zwar,

Und loben, schier begeistert:

Wie edel dein Gedankenflug,

Wie du die Form bemeistert.

Sie pflegen auch beim Glase Wein

Ein Vivat dir zu bringen

Und manchen Schlachtgesang von dir

Lautbrüllend nachzusingen.

Der Knecht singt gern ein Freiheitslied

Des Abends in der Schenke:

Das fördert die Verdauungskraft,

Und würzet die Getränke.

Heinrich Heine poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Heine, Heinrich

Charles Guérin

(1873-1907)

La maison dort

La maison dort au coeur de quelque vieille ville

Où des dames s’en vont, lasses de bonnes oeuvres,

S’assoupir en suivant l’office de six heures,

Ville où le rouet gris de l’ennui se dévide.

Dans la cour un bassin où pleurent les eaux vives

D’avoir vu verdir les Tritons et d’être seules.

Et la maison laisse gémir les eaux jaseuses ;

Ses yeux sont noirs où s’avivaient jadis les vitres,

Et, vers le soir, les cuivres du soleil s’éteignent

Sur les plafonds tendus de terreuses dentelles

Qu’un coup de vent parfois tord comme des écharpes.

Les mites ont aimé dans les tentures ternes ;

Aussi, charme décoloré des chambres, charme

Des rêves qu’on a trop songés et qui se taisent.

Charles Guérin poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, CLASSIC POETRY

Stefan Georg

(1868-1933)

STRAND

O lenken wir hinweg von wellenauen!

Die wenn auch wild im wollen und mit düsterm rollen

Nur dulden scheuer möwen schwingenschlag

Und stet des keuschen himmels farben schauen.

Wir heuchelten zu lang schon vor dem tag.

Zu weihern grün mit moor und blumenspuren

Wo gras und laub und ranken wirr und üppig schwanken

Und ewger abend einen altar weiht!

Die schwäne die da aus der buchtung fuhren ·

Geheimnisreich · sind unser brautgeleit.

Die lust entführt uns aus dem fahlen norden:

Wo deine lippen glühen fremde kelche blühen –

Und fliesst dein leib dahin wie blütenschnee

Dann rauschen alle stauden in akkorden

Und werden lorbeer tee und aloe.

Stefan Georg poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, George, Stefan

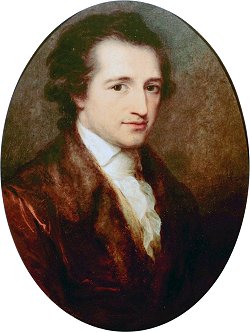

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

(1749-1832)

Liebhaber in allen Gestalten

Ich wollt, ich wär ein Fisch,

So hurtig und frisch;

Und kämst du zu anglen,

Ich würde nicht manglen.

Ich wollt, ich wär ein Fisch,

So hurtig und frisch.

Ich wollt, ich wär ein Pferd,

Da wär ich dir wert.

O wär ich ein Wagen,

Bequem dich zu tragen.

Ich wollt, ich wär ein Pferd,

Da wär ich dir wert.

Ich wollt, ich wäre Gold,

Dir immer im Sold;

Und tätst du was kaufen,

Käm ich wieder gelaufen.

Ich wollt, ich wäre Gold,

Dir immer im Sold.

Ich wollt, ich wär treu,

Mein Liebchen stets neu;

Ich wollt mich verheißen,

Wollt nimmer verreisen.

Ich wollt, ich wär treu,

Mein Liebchen stets neu.

Ich wollt, ich wär alt

Und runzlig und kalt;

Tätst du mir’s versagen,

Da könnt mich’s nicht plagen.

Ich wollt, ich wär alt

Und runzlig und kalt.

Wär ich Affe sogleich,

Voll neckender Streich’;

Hätt was dich verdrossen,

So macht ich dir Possen.

Wär ich Affe sogleich,

Voll neckender Streich’.

Wär ich gut wie ein Schaf,

Wie der Löwe so brav;

Hätt Augen wie’s Lüchschen

Und Listen wie’s Füchschen.

Wär ich gut wie ein Schaf,

Wie der Löwe so brav.

Was alles ich wär,

Das gönnt ich dir sehr;

Mit fürstlichen Gaben,

Du solltest mich haben.

Was alles ich wär,

Das gönnt ich dir sehr.

Doch bin ich, wie ich bin,

Und nimm mich nur hin!

Willst du beßre besitzen,

So laß dir sie schnitzen.

Ich bin nun, wie ich bin;

So nimm mich nur hin!

Goethe poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Friedrich Hebbel

(1813-1863)

Knabentod

Vom Berg, der Knab’,

Der zieht hinab

In heißen Sommertagen;

Im Tannenwald,

Da macht er Halt,

Er kann sich kaum noch tragen.

Den wilden Bach,

Er sieht ihn jach

In’s Thal herunter schäumen;

Ihn dürstet sehr,

Nun noch viel mehr:

Nur hin! Wer würde säumen!

Da ist die Flut!

O, in der Glut,

Was kann so köstlich blinken!

Er schöpft und trinkt,

Er stürzt und sinkt

Und trinkt noch im Versinken!

Das Lied ist aus,

Und macht’s dir Graus:

Wer wird’s im Winter singen!

Zur Sommerzeit

Bist du bereit,

Dem Knaben nachzuspringen.

Friedrich Hebbel poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, CLASSIC POETRY

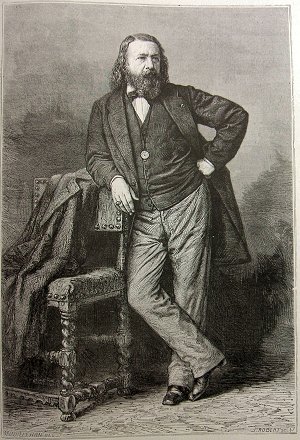

Théophile Gautier

(1811-1872)

A deux beaux yeux

Vous avez un regard singulier et charmant ;

Comme la lune au fond du lac qui la reflète,

Votre prunelle, où brille une humide paillette,

Au coin de vos doux yeux roule languissamment ;

Ils semblent avoir pris ses feux au diamant ;

Ils sont de plus belle eau qu’une perle parfaite,

Et vos grands cils émus, de leur aile inquiète,

Ne voilent qu’à demi leur vif rayonnement.

Mille petits amours, à leur miroir de flamme,

Se viennent regarder et s’y trouvent plus beaux,

Et les désirs y vont rallumer leurs flambeaux.

Ils sont si transparents, qu’ils laissent voir votre âme,

Comme une fleur céleste au calice idéal

Que l’on apercevrait à travers un cristal.

Théophile Gautier poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Gautier, Théophile

A. E. Housman

(1859-1936)

Eight O’Clock

He stood, and heard the steeple

Sprinkle the quarters on the morning town.

One, two, three, four, to market-place and people

It tossed them down.

Strapped, noosed, nighing his hour,

He stood and counted them and cursed his luck;

And then the clock collected in the tower

Its strength, and struck.

A. E. Housman poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Housman, A.E.

Charles Guérin

(1873 – 1907 )

Epitaphe pour lui-même

Il fut le très subtil musicien des vents

Qui se plaignent en de nocturnes symphonies ;

Il nota le murmure des herbes jaunies

Entre les pavés gris des cours d’anciens couvents.

Il trouva sur la viole des dévots servants

Pour ses maîtresses des tendresses infinies ;

Il égrena les ineffables litanies

Ou s’alanguissent tous les amoureux fervents.

Un soir, la chair brisée aux voluptés divines,

Il détourna du ciel son front fleuri d’épines,

Et se coucha, les pieds meurtris et le coeur las.

Ô toi, qui, dégoûté du rire et de la lutte

Odieuse, vibras aux sanglots de sa flûte,

Poète, ralentis le pas : cy dort Heirclas.

Charles Guérin poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive G-H, CLASSIC POETRY

The Sorrows of Young Werther (06)

by J.W. von Goethe

17 May 1771

I have made all sorts of acquaintances, but have as yet found no society. I know not what attraction I possess for the people, so many of them like me, and attach themselves to me; and then I feel sorry when the road we pursue together goes only a short distance. If you inquire what the people are like here, I must answer, “The same as everywhere.” The human race is but a monotonous affair. Most of them labour the greater part of their time for mere subsistence; and the scanty portion of freedom which remains to them so troubles them that they use every exertion to get rid of it. Oh, the destiny of man!

But they are a right good sort of people. If I occasionally forget myself, and take part in the innocent pleasures which are not yet forbidden to the peasantry, and enjoy myself, for instance, with genuine freedom and sincerity, round a well-covered table, or arrange an excursion or a dance opportunely, and so forth, all this produces a good effect upon my disposition; only I must forget that there lie dormant within me so many other qualities which moulder uselessly, and which I am obliged to keep carefully concealed. Ah! this thought affects my spirits fearfully. And yet to be misunderstood is the fate of the like of us.

Alas, that the friend of my youth is gone! Alas, that I ever knew her! Imight say to myself, “You are a dreamer to seek what is not to be found here below.” But she has been mine. I have possessed that heart, that noble soul, in whose presence I seemed to be more than I really was, because I was all that I could be. Good heavens! did then a single power of my soul remain unexercised? In her presence could I not display, to its full extent, that mysterious feeling with which my heart embraces nature? Was not our intercourse a perpetual web of the finest emotions, of the keenest wit, the varieties of which, even in their very eccentricity, bore the stamp of genius? Alas! the few years by which she was my senior brought her to the grave before me. Never can I forget her firm mind or her heavenly patience.

A few days ago I met a certain young V–, a frank, open fellow, with a most pleasing countenance. He has just left the university, does not deem himself overwise, but believes he knows more than other people. He has worked hard, as I can perceive from many circumstances, and, in short, possesses a large stock of information. When he heard that I am drawing a good deal, and that I know Greek (two wonderful things for this part of the country), he came to see me, and displayed his whole store of learning, from Batteaux to Wood, from De Piles to Winkelmann: he assured me he had read through the first part of Sultzer’s theory, and also possessed a manuscript of Heyne’s work on the study of the antique. I allowed it all to pass.

I have become acquainted, also, with a very worthy person, the district judge, a frank and open-hearted man. I am told it is a most delightful thing to see him in the midst of his children, of whom he has nine. His eldest daughter especially is highly spoken of. He has invited me to go and see him, and I intend to do so on the first opportunity. He lives at one of the royal hunting-lodges, which can be reached from here in an hour and a half by walking, and which he obtained leave to inhabit after the loss of his wife, as it is so painful to him to reside in town and at the court.

There have also come in my way a few other originals of a questionable sort, who are in all respects undesirable, and most intolerable in their demonstration of friendship. Good-bye. This letter will please you: it is quite historical.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Archive G-H, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

The Sorrows of Young Werther (05)

by J.W. von Goethe

15 May 1771

The common people of the place know me already, and love me, particularly the children. When at first I associated with them, and inquired in a friendly tone about their various trifles, some fancied that I wished to ridicule them, and turned from me in exceeding ill-humour. I did not allow that circumstance to grieve me: I only felt most keenly what I have often before observed. Persons who can claim a certain rank keep themselves coldly aloof from the common people, as though they feared to lose their importance by the contact; whilst wanton idlers, and such as are prone to bad joking, affect to descend to their level, only to make the poor people feel their impertinence all the more keenly.

I know very well that we are not all equal, nor can be so; but it is my opinion that he who avoids the common people, in order not to lose their respect, is as much to blame as a coward who hides himself from his enemy because he fears defeat. The other day I went to the fountain, and found a young servant-girl, who had set her pitcher on the lowest step, and looked around to see if one of her companions was approaching to place it on her head. I ran down, and looked at her. “Shall I help you, pretty lass?” said I. She blushed deeply. “Oh, sir!” she exclaimed. “No ceremony!” I replied. Sheadjusted her head-gear, and I helped her. She thanked me, and ascended the steps.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Archive G-H, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature