Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

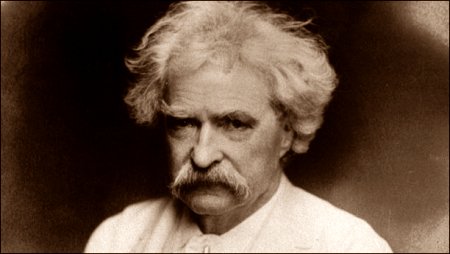

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

Post-Mortem Poetry

In Philadelphia they have a custom which it would be pleasant to see adopted throughout the land. It is that of appending to published death-notices a little verse or two of comforting poetry. Any one who is in the habit of reading the daily Philadelphia Ledger, must frequently be touched by these plaintive tributes to extinguished worth. In Philadelphia, the departure of a child is a circumstance which is not more surely followed by a burial than by the accustomed solacing poesy in the Public Ledger. In that city death loses half its terror because the knowledge of its presence comes thus disguised in the sweet drapery of verse. For instance, in a late Ledger I find the following (I change the surname):

“Died

“Hawks.—On the 17th inst., Clara, the daughter of Ephraim and Laura Hawks, aged 21 months and 2 days.

“That merry shout no more I hear,

No laughing child I see,

No little arms are round my neck,

No feet upon my knee;

No kisses drop upon my cheek,

These lips are sealed to me.

Dear Lord, how could I give Clara up

To any but to Thee?”

A child thus mourned could not die wholly discontended. From the Ledger of the same date I make the following extract, merely changing the surname, as before:

“Becket.—On Sunday morning, 19th inst., John P., infant son of George and Julia Becket, aged 1 year, 6 months, and 15 days.

“That merry shout no more I hear,

No laughing child I see,

No little arms are round my neck,

No feet upon my knee;

No kisses drop upon my cheek,

These lips are sealed to me.

Dear Lord, how could I give Johnnie up

To any but to Thee?”

The similarity of the emotions as produced in the mourners in these two instances is remarkably evidenced by the singular similarity of thought which they experienced, and the surprising coincidence of language used by them to give it expression.

In the same journal, of the same date, I find the following (surname suppressed, as before):

“Wagner.—On the 10th inst., Ferguson G., the son of William L. and Martha Theresa Wagner, aged 4 weeks and 1 day.

“That merry shout no more I hear,

No laughing child I see,

No little arms are round my neck,

No feet upon my knee;

No kisses drop upon my cheek,

These lips are sealed to me.

Dear Lord, how could I give Ferguson up

To any but to Thee?”

It is strange what power the reiteration of an essentially poetical thought has upon one’s feelings. When we take up theLedger and read the poetry about little Clara, we feel an unaccountable depression of the spirits. When we drift further down the column and read the poetry about little Johnnie, the depression of spirits acquires an added emphasis, and we experience tangible suffering. When we saunter along down the column further still and read the poetry about little Ferguson, the word torture but vaguely suggests the anguish that rends us.

In the Ledger (same copy referred to above) I find the following (I alter surname, as usual):

“Welch.—On the 5th inst., Mary C. Welch, wife of William B. Welch, and daughter of Catharine and George W. Markland, in the 29th year of her age.

“A mother dear, a mother kind,

Has gone and left us all behind.

Cease to weep, for tears are vain,

Mother dear is out of pain.

“Farewell, husband, children dear,

Serve thy God with filial fear,

And meet me in the land above,

Where all is peace, and joy, and love.”

What could be sweeter than that? No collection of salient facts (without reduction to tabular form) could be more succinctly stated than is done in the first stanza by the surviving relatives, and no more concise and comprehensive programme of farewells, post-mortuary general orders, etc., could be framed in any form than is done in verse by deceased in the last stanza. These things insensibly make us wiser and tenderer, and better. Another extract:

“Ball.—On the morning of the 15th inst, Mary E., daughter of John and Sarah F. Ball.

“’Tis sweet to rest in lively hope

That when my change shall come

Angels will hover round my bed,

To waft my spirit home.”

The following is apparently the customary form for heads of families:

“Burns.—On the 20th inst., Michael Burns, aged 40 years.

“Dearest father, thou hast left us,

Here thy loss we deeply feel;

But ’tis God that has bereft us,

He can all our sorrows heal.

“Funeral at 2 o’clock sharp.”

There is something very simple and pleasant about the following, which, in Philadelphia, seems to be the usual form for consumptives of long standing. (It deplores four distinct cases in the single copy of the Ledger which lies on the Memoranda editorial table):

“Bromley.—On the 29th inst., of consumption, Philip Bromley, in the 50th year of his age.

“Affliction sore long time he bore,

Physicians were in vain—

Till God at last did hear him mourn,

And eased him of his pain.

“The friend whom death from us has torn,

We did not think so soon to part;

An anxious care now sinks the thorn

Still deeper in our bleeding heart.”

This beautiful creation loses nothing by repetition. On the contrary, the oftener one sees it in the Ledger, the more grand and awe-inspiring it seems.

With one more extract I will close:

“Doble.—On the 4th inst., Samuel Peveril Worthington Doble, aged 4 days.

“Our little Sammy’s gone,

His tiny spirit’s fled;

Our little boy we loved so dear

Lies sleeping with the dead.

“A tear within a father’s eye,

A mother’s aching heart,

Can only tell the agony

How hard it is to part.”

Could anything be more plaintive than that, without requiring further concessions of grammar? Could anything be likely to do more towards reconciling deceased to circumstances, and making him willing to go? Perhaps not. The power of song can hardly be estimated. There is an element about some poetry which is able to make even physical suffering and death cheerful things to contemplate and consummations to be desired. This element is present in the mortuary poetry of Philadelphia degree of development.

The custom I have been treating of is one that should be adopted in all the cities of the land.

It is said that once a man of small consequence died, and the Rev. T. K. Beecher was asked to preach the funeral sermon—a man who abhors the lauding of people, either dead or alive, except in dignified and simple language, and then only for merits which they actually possessed or possess, not merits which they merely ought to have possessed. The friends of the deceased got up a stately funeral. They must have had misgivings that the corpse might not be praised strongly enough, for they prepared some manuscript headings and notes in which nothing was left unsaid on that subject that a fervid imagination and an unabridged dictionary could compile, and these they handed handed to the minister as he entered the pulpit. They were merely intended as suggestions, and so the friends were filled with consternation when the minister stood up in the pulpit and proceeded to read off the curious odds and ends in ghastly detail and in a loud voice! And their consternation solidified to petrification when he paused at the end, contemplated the multitude reflectively, and then said, impressively:

“The man would be a fool who tried to add anything to that. Let us pray!”

And with the same strict adhesion to truth it can be said that the man would be a fool who tried to add anything to the following transcendent obituary poem. There is something so innocent, so guileless, so complacent, so unearthly serene and self-satisfied about this peerless “hogwash,” that the man must be made of stone who can read it without a dulcet ecstasy creeping along his backbone and quivering in his marrow. There is no need to say that this poem is genuine and in earnest, for its proofs are written all over its face. An ingenious scribbler might imitate it after a fashion, but Shakespeare himself could not counterfeit it. It is noticeable that the country editor who published it did not know that it was a treasure and the most perfect thing of its kind that the storehouses and museums of literature could show. He did not dare to say no to the dread poet—for such a poet must have been something of an apparition—but he just shovelled it into his paper anywhere that came handy, and felt ashamed, and put that disgusted “Published by Request” over it, and hoped that his subscribers would overlook it or not feel an impulse to read it:

“(Published by request)

“Lines

‘Composed on the death of Samuel and Catharine Belknap’s children

“By M. A. Glaze

“Friends and neighbors all draw near,

And listen to what I have to say;

And never leave your children dear

When they are small, and go away.

“But always think of that sad fate,

That happened in year of ’63;

Four children with a house did burn,

Think of their awful agony.

“Their mother she had gone away,

And left them there alone to stay;

The house took fire and down did burn,

Before their mother did return.

“Their piteous cry the neighbors heard,

And then the cry of fire was given;

But, ah! before they could them reach,

Their little spirits had flown to heaven.

“Their father he to war had gone,

And on the battle-field was slain;

But little did he think when he went away,

But what on earth they would meet again.

“The neighbors often told his wife

Not to leave his children there,

Unless she got someone to stay,

And of the little ones take care.

“The oldest he was years not six,

And the youngest only eleven months old,

But often she had left them there alone,

As, by the neighbors, I have been told.

“How can she bear to see the place.

Where she so oft has left them there,

Without a single one to look to them,

Or of the little ones to take good care.

“Oh, can she look upon the spot,

Whereunder their little burnt bones lay,

But what she thinks she hears them say,

‘’Twas God had pity, and took us on high.’

“And there may she kneel down and pray,

And ask God her to forgive;

And she may lead a different life

While she on earth remains to live.

“Her husband and her children too,

God has took from pain and woe.

May she reform and mend her ways,

That she may also to them go.

“And when it is God’s holy will,

O, may she be prepared

To meet her God and friends in peace,

And leave this world of care.”

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Galerie des Morts, Twain, Mark

.jpg)

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

The Danger of Lying in Bed

The man in the ticket-office said:

“Have an accident insurance ticket, also?”

“No,” I said, after studying the matter over a little.

“No, I believe not; I am going to be travelling by rail all day to-day. However, to-morrow I don’t travel. Give me one for to-morrow.”

The man looked puzzled. He said:

“But it is for accident insurance, and if you are going to travel by rail—”

“If I am going to travel by rail I sha’n’t need it. Lying at home in bed is the thing I am afraid of.”

I had been looking into this matter. Last year I travelled twenty thousand miles, almost entirely by rail; the year before, I travelled over twenty-five thousand miles, half by sea and half by rail; and the year before that I travelled in the neighborhood of ten thousand miles, exclusively by rail. I suppose if I put in all the little odd journeys here and there, I may say I have travelled sixty thousand miles during the three years I have mentioned. And never an accident.

For a good while I said to myself every morning:

“Now I have escaped thus far, and so the chances are just that much increased that I shall catch it this time. I will be shrewd, and buy an accident ticket.” And to a dead moral certainty I drew a blank, and went to bed that night without a joint started or a bone splintered. I got tired of that sort of daily bother, and fell to buying accident tickets that were good for a month. I said to myself, “A man can’t buy thirty blanks in one bundle.”

But I was mistaken. There was never a prize in the lot. I could read of railway accidents every day—the newspaper atmosphere was foggy with them; but somehow they never came my way. I found I had spent a good deal of money in the accident business, and had nothing to show for it. My suspicions were aroused, and I began to hunt around for somebody that had won in this lottery. I found plenty of people who had invested, but not an individual that had ever had an accident or made a cent. I stopped buying accident tickets and went to ciphering. The result was astounding. The Peril Lay not in Travelling, but in staying at home.

I hunted up statistics, and was amazed to find that after all the glaring newspaper headings concerning railroad disasters, less than three hundred people had really lost their lives by those disasters in the preceding twelve months. The Erie road was set down as the most murderous in the list. It had killed forty-six—or twenty-six, I do not exactly remember which, but I know the number was double that of any other road. But the fact straightway suggested itself that the Erie was an immensely long road, and did more business than any other in the country; so the double number of killed ceased to be matter for surprise.

By further figuring, it appeared that between New York and Rochester the Erie ran eight passenger trains each way every day—sixteen altogether; and carried a daily average of 6000 persons. That is about a million in six months—the population of New York City. Well, the Erie kills from thirteen to twenty- three persons out of its million in six months; and in the same time 13,000 of New York’s million die in their beds! My flesh crept, my hair stood on end. “This is appalling!” I said. “The danger isn’t in travelling by rail, but in trusting to those deadly beds. I will never sleep in a bed again.”

I had figured on considerably less than one-half the length of the Erie road. It was plain that the entire road must transport at least eleven or twelve thousand people every day. There are many short roads running out of Boston that do fully half as much; a great many such roads. There are many roads scattered about the Union that do a prodigious passenger business. Therefore it was fair to presume that an average of 2500 passengers a day for each road in the country would be about correct. There are 846 railway lines in our country, and 846 times 2500 are 2,115,000. So the railways of America move more than two millions of people every day; six hundred and fifty millions of people a year, without counting the Sundays. They do that, too—there is no question about it; though where they get the raw material is clear beyond the jurisdiction of my arithmetic; for I have hunted the census through and through, and I find that there are not that many people in the United States, by a matter of six hundred and ten millions at the very least. They must use some of the same people over again, likely.

San Francisco is one-eighth as populous as New York; there are 60 deaths a week in the former and 500 a week in the latter—if they have luck. That is 3120 deaths a year in San Francisco, and eight times as many in New York—say about 25,000 or 26,000. The health of the two places is the same. So we will let it stand as a fair presumption that this will hold good all over the country, and that consequently 25,000 out of every million of people we have must die every year. That amounts to one-fortieth of our total population. One million of us, then, die annually. Out of this million ten or twelve thousand are stabbed, shot, drowned, hanged, poisoned, or meet a similarly violent death in some other popular way, such as perishing by kerosene lamp and hoop-skirt conflagrations, getting buried in coal-mines, falling off house-tops, breaking through church or lecture-room floors, taking patent medicines, or committing suicide in other forms. The Erie railroad kills from 23 to 46; the other 845 railroads kill an average of one-third of a man each; and the rest of that million, amounting in the aggregate to the appalling figure of nine hundred and eighty-seven thousand six hundred and thirty-one corpses, die naturally in their beds!

You will excuse me from taking any more chances on those beds. The railroads are good enough for me.

And my advice to all people is, Don’t stay at home any more than you can help; but when you have got to stay at home a while, buy a package of those insurance tickets and sit up nights. You cannot be too cautious.

[One can see now why I answered that ticket-agent in the manner recorded at the top of this sketch.]

The moral of this composition is, that thoughtless people grumble more than is fair about railroad management in the United States. When we consider that every day and night of the year full fourteen thousand railway trains of various kinds, freighted with life and armed with death, go thundering over the land, the marvel is, not that they kill three hundred human beings in a twelvemonth, but that they do not kill three hundred times three hundred!

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

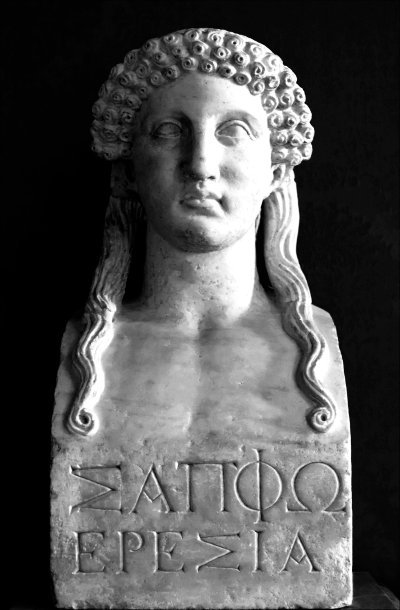

Sappho

(c. 630–570 b.c.)

Sleep, darling

Sleep, darling

I have a small

daughter called

Cleis, who is

like a golden

flower

I wouldn’t

take all Croesus’

kingdom with love

thrown in, for her

—

Don’t ask me what to wear

I have no embroidered

headband from Sardis to

give you, Cleis, such as

I wore

and my mother

always said that in her

day a purple ribbon

looped in the hair was thought

to be high style indeed

but we were dark:

a girl

whose hair is yellower than

torchlight should wear no

headdress but fresh flowers

Sappho

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

.jpg)

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Sappho

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

The First Writing-Machines

From My Unpublished Autobiography

Some days ago a correspondent sent in an old type-written sheet, faded by age, containing the following letter over the signature of Mark Twain:

“Hartford, March 19, 1875.

“Please do not use my name in any way. Please do not even divulge the fact that I own a machine. I have entirely stopped using the type-writer, for the reason that I never could write a letter with it to anybody without receiving a request by return mail that I would not only describe the machine, but state what progress I had made in the use of it, etc., etc. I don’t like to write letters, and so I don’t want people to know I own this curiosity-breeding little joker.”

A note was sent to Mr. Clemens asking him if the letter was genuine and whether he really had a type- writer as long ago as that. Mr. Clemens replied that his best answer is in the following chapter from his unpublished autobiography:

1904. Villa Quarto, Florence, January.

Dictating autobiography to a type-writer is a new experience for me, but it goes very well, and is going to save time and “language”—the kind of language that soothes vexation.

I have dictated to a type-writer before—but not autobiography. Between that experience and the present one there lies a mighty gap—more than thirty years! It is a sort of lifetime. In that wide interval much has happened—to the type-machine as well as to the rest of us. At the beginning of that interval a type- machine was a curiosity. The person who owned one was a curiosity, too. But now it is the other way about: the person who doesn’t own one is a curiosity. I saw a type-machine for the first time in—what year? I suppose it was 1873—because Nasby was with me at the time, and it was in Boston. We must have been lecturing, or we could not have been in Boston, I take it. I quitted the platform that season.

But never mind about that, it is no matter. Nasby and I saw the machine through a window, and went in to look at it. The salesman explained it to us, showed us samples of its work, and said it could do fifty- seven words a minute—a statement which we frankly confessed that we did not believe. So he put his type-girl to work, and we timed her by the watch. She actually did the fifty-seven in sixty seconds. We were partly convinced, but said it probably couldn’t happen again. But it did. We timed the girl over and over again—with the same result always: she won out. She did her work on narrow slips of paper, and we pocketed them as fast as she turned them out, to show as curiosities. The price of the machine was $125. I bought one, and we went away very much excited.

At the hotel we got out our slips and were a little disappointed to find that they all contained the same words. The girl had economized time and labor by using a formula which she knew by heart. However, we argued—safely enough—that the first type-girl must naturally take rank with the first billiard-player: neither of them could be expected to get out of the game any more than a third or a half of what was in it. If the machine survived—if it survived—experts would come to the front, by-and-by, who would double this girl’s output without a doubt. They would do one hundred words a minute—my talking speed on the platform. That score has long ago been beaten.

At home I played with the toy, repeating and repeating and repeating “The Boy stood on the Burning Deck,” until I could turn that boy’s adventure out at the rate of twelve words a minute; then I resumed the pen, for business, and only worked the machine to astonish inquiring visitors. They carried off many reams of the boy and his burning deck.

By-and-by I hired a young woman, and did my first dictating (letters, merely), and my last until now. The machine did not do both capitals and lower case (as now), but only capitals. Gothic capitals they were, and sufficiently ugly. I remember the first letter I dictated. It was to Edward Bok, who was a boy then. I was not acquainted with him at that time. His present enterprising spirit is not new—he had it in that early day. He was accumulating autographs, and was not content with mere signatures, he wanted a whole autograph letter. I furnished it—in type-machine capitals, signature and all. It was long; it was a sermon; it contained advice; also reproaches. I said writing was my trade, my bread-and- butter; I said it was not fair to ask a man to give away samples of his trade; would he ask the blacksmith for a horseshoe? would he ask the doctor for a corpse?

Mark Twain short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

An Entertaining Article

I take the following paragraph from an article in the Boston Advertiser:

“Perhaps the most successful flights of the humor of Mark Twain have been descriptions of the persons who did not appreciate his humor at all. We have become familiar with the Californians who were thrilled with terror by his burlesque of a newspaper reporter’s way of telling a story, and we have heard of the Pennsylvania clergyman who sadly returned his Innocents Abroad to the book-agent with the remark that ‘the man who could shed tears over the tomb of Adam must be an idiot.’ But Mark Twain may now add a much more glorious instance to his string of trophies. The Saturday Review, in its number of October 8th, reviews his book of travels, which has been republished in England, and reviews it seriously. We can imagine the delight of the humorist in reading this tribute to his power; and indeed it is so amusing in itself that he can hardly do better than reproduce the article in full in his next monthly Memoranda.”

(Publishing the above paragraph thus, gives me a sort of authority for reproducing the Saturday Review’s article in full in these pages. I dearly wanted to do it, for I cannot write anything half so delicious myself. If I had a cast-iron dog that could read this English criticism and preserve his austerity, I would drive him off the door-step.)

(From the London “Saturday Review.”)

“Reviews of New Books”

“The Innocents Abroad. A Book of Travels. By Mark Twain. London: Hotten, publisher. 1870. “Lord Macaulay died too soon. We never felt this so deeply as when we finished the last chapter of the above- named extravagant work. Macaulay died too soon—for none but he could mete out complete and comprehensive justice to the insolence, the impertinence, the presumption, the mendacity, and, above all, the majestic ignorance of this author.

“To say that the Innocents Abroad is a curious book, would be to use the faintest language—would be to speak of the Matterhorn as a neat elevation or of Niagara as being ‘nice’ or ‘pretty.’ ‘Curious’ is too tame a word wherewith to describe the imposing insanity of this work. There is no word that is large enough or long enough. Let us, therefore, photograph a passing glimpse of book and author, and trust the rest to the reader. Let the cultivated English student of human nature picture to himself this Mark Twain as a person capable of doing the following-described things—and not only doing them, but with incredible innocence printing them calmly and tranquilly in a book. For instance:

“He states that he entered a hair-dresser’s in Paris to get shaved, and the first ‘rake’ the barber gave with his razor it loosened his ‘hide’ and lifted him out of the chair.

“This is unquestionably exaggerated. In Florence he was so annoyed by beggars that he pretends to have seized and eaten one in a frantic spirit of revenge. There is, of course, no truth in this. He gives at full length a theatrical programme seventeen or eighteen hundred years old, which he professes to have found in the ruins of the Coliseum, among the dirt and mould and rubbish. It is a sufficient comment upon this statement to remark that even a cast-iron programme would not have lasted so long under such circumstances. In Greece he plainly betrays both fright and flight upon one occasion, but with frozen efforntery puts the latter in this falsely tame form: ‘We sidled towards the Piræus.’ ‘Sidled,’ indeed! He does not hesitate to intimate that at Ephesus, when his mule strayed from the proper course, he got down, took him under his arm, carried him to the road again, pointed him right, remounted, and went to sleep contentedly till it was time to restore the beast to the path once more. He states that a growing youth among his ship’s passengers was in the constant habit of appeasing his hunger with soap and oakum between meals. In Palestine he tells of ants that came eleven miles to spend the summer in the desert and brought their provisions with them; yet he shows by his description of the country that the feat was an impossibility. He mentions, as if it were the most commonplace of matters, that he cut a Moslem in two in broad daylight in Jerusalem, with Godfrey de Bouillon’s sword, and would have shed more blood if he had had a graveyard of his own. These statements are unworthy a moment’s attention. Mr. Twain or any other foreigner who did such a thing in Jerusalem would be mobbed, and would infallibly lose his life. But why go on? Why repeat more of his audacious and exasperating falsehoods? Let us close fittingly with this one: he affirms that ‘in the mosque of St. Sophia at Constantinople I got my feet so stuck up with a complication of gums, slime, and general impurity, that I wore out more than two thousand pair of bootjacks getting my boots off that night, and even then some Christian hide peeled off with them.’ It is monstrous. Such statements are simply lies—there is no other name for them. Will the reader longer marvel at the brutal ignorance that pervades the American nation when we tell him that we are informed upon perfectly good authority that this extravagant compilation of falsehoods, this exhaustless mine of stupendous lies, this Innocents Abroad, has actually been adopted by the schools and colleges of several of the States as a text-book!

“But if his falsehoods are distressing, his innocence and his ignorance are enough to make one burn the book and despise the author. In one place he was so appalled at the sudden spectacle of a murdered man, unveiled by the moonlight, that he jumped out of the window, going through sash and all, and then remarks with the most childlike simplicity that he ‘was not scared, but was considerably agitated.’ It puts us out of patience to note that the simpleton is densely unconscious that Lucrezia Borgia ever existed off the stage. He is vulgarly ignorant of all foreign languages, but is frank enough to criticise the Italians’ use of their own tongue. He says they spell the name of their great painter ‘Vinci, but pronounce it Vinchy’—and then adds with a naïveté possible only to helpless ignorance, ‘foreigners always spell better than they pronounce.’ In another place he commits the bald absurdity of putting the phrase ‘tare an ouns’ into an Italian’s mouth. In Rome he unhesitatingly believes the legend that St. Philip Neri’s heart was so inflamed with divine love that it burst his ribs—believes it wholly because an author with a learned list of university degrees strung after his name endorses it—‘otherwise,’ says this gentle idiot, ‘I should have felt a curiosity to know what Philip had for dinner.’ Our author makes a long, fatiguing journey to the Grotto del Cane on purpose to test its poisoning powers on a dog—got elaborately ready for the experiment, and then discovered that he had no dog. A wiser person would have kept such a thing discreetly to himself, but with this harmless creature everything comes out. He hurts his foot in a rut two thousand years old in exhumed Pompeii, and presently, when staring at one of the cinder-like corpses unearthed in the next square, conceives the idea that may be it is the remains of the ancient Street Commissioner, and straightway his horror softens down to a sort of chirpy contentment with the condition of things. In Damascus he visits the well of Ananias, three thousand years old, and is as surprised and delighted as a child to find that the water is ‘as pure and fresh as if the well had been dug yesterday.’ In the Holy Land he gags desperately at the hard Arabic and Hebrew Biblical names, and finally concludes to call them Baldwinsville, Williamsburgh, and so on, ‘for convenience of spelling.’

“We have thus spoken freely of this man’s stupefying simplicity and innocence, but we cannot deal similarly with his colossal ignorance. We do not know where to begin. And if we knew where to begin, we certainly would not know where to leave off. We will give one specimen, and one only. He did not know, until he got to Rome, that Michael Angelo was dead! And then, instead of crawling away and hiding his shameful ignorance somewhere, he proceeds to express a pious, grateful sort of satisfaction that he is gone and out of his troubles!

“No, the reader may seek out the author’s exhibition of his uncultivation for himself. The book is absolutely dangerous, considering the magnitude and variety of its misstatements, and the convincing confidence with which they are made. And yet it is a text-book in the schools of America.

The poor blunderer mouses among the sublime creations of the Old Masters, trying to acquire the elegant proficiency in art-knowledge, which he has a groping sort of comprehension is a proper thing for the travelled man to be able to display. But what is the manner of his study? And what is the progress he achieves? To what extent does he familiarize himself with the great pictures of Italy, and what degree of appreciation does he arrive at? Read:

“‘When we see a monk going about with a lion and looking up into heaven, we know that that is St. Mark. When we see a monk with a book and a pen, looking tranquilly up to heaven, trying to think of a word, we know that that is St. Matthew. When we see a monk sitting on a rock, looking tranquilly up to heaven, with a human skull beside him, and without other baggage, we know that that is St. Jerome. Because we know that he always went flying light in the matter of baggage. When we see other monks looking tranquilly up to heaven, but having no trade-mark, we always ask who those parties are. We do this because we humbly wish to learn.’

“He then enumerates the thousands and thousands of copies of these several pictures which he has seen, and adds with accustomed simplicity that he feels encouraged to believe that when he has seen ‘Some More’ of each, and had a larger experience, he will eventually ‘begin to take an absorbing interest in them’—the vulgar boor.

“That we have shown this to be a remarkable book, we think no one will deny. That it is a pernicious book to place in the hands of the confiding and uninformed, we think we have also shown. That the book is a deliberate and wicked creation of a diseased mind, is apparent upon every page. Having placed our judgement thus upon record, let us close with what charity we can, by remarking that even in this volume there is some good to be found; for whenever the author talks of his own country and lets Europe alone, he never fails to make himself interesting, and not only interesting, but instructive. No one can read without benefit his occasional chapters and paragraphs, about life in the gold and silver mines of California and Nevada; about the Indians of the plains and deserts of the West, and their cannibalism; about the raising of vegetables in kegs of gunpowder by the aid of two or three teaspoonfuls of guano; about the moving of small farms from place to place at night in wheelbarrows to avoid taxes; and about a sort of cows and mules in the Humboldt mines, that climb down chimneys and disturb the people at night. These matters are not only new, but are well worth knowing. It is a pity the author did not put in more of the same kind. His book is well written and is exceedingly entertaining, and so it just barely escaped being quite valuable also.”

(One month later)

Latterly I have received several letters, and see a number of newspaper paragraphs, all upon a certain subject, and all of about the same tenor. I here give honest specimens. One is from a New York paper, one is from a letter from an old friend, and one is from a letter from a New York publisher who is a stranger to me. I humbly endeavor to make these bits tooth-some with the remark that the article they are praising (which appeared in the December Galaxy, and pretended to be a criticism from the London Saturday Review on my Innocents Abroad) was written by myself, every line of it:

“The Herald says the richest thing out is the ‘serious critique’ in the London Saturday Review, on Mark Twain’s Innocents Abroad. We thought before we read it that it must be ‘serious,’ as everybody said so, and were even ready to shed a few tears; but since perusing it, we are bound to confess that next to Mark Twain’s ‘Jumping Frog’ it’s the finest bit of humor and sarcasm that we’ve come across in many a day.”

(I do not get a compliment like that every day.)

“I used to think that your writings were pretty good, but after reading the criticism in The Galaxy from the London Review, have discovered what an ass I must have been. If suggestions are in order, mine is, that you put that article in your next edition of the Innocents, as an extra chapter, if you are not afraid to put your own humor in competition with it. It is as rich a thing as I ever read.”

(Which is strong commendation from a book publisher.)

“The London Reviewer, my friend, is not the stupid, ‘serious’ creature he pretends to be, I think; but, on the contrary, has a keen appreciation and enjoyment of your book. As I read his article in The Galaxy, I could imagine him giving vent to many a hearty laugh. But he is writing for Catholics and Established Church people, and high-toned, antiquated, conservative gentility, whom it is a delight to him to help you shock, while he pretends to shake his head with owlish density. He is a magnificent humorist himself.” (Now that is graceful and handsome. I take off my hat to my life-long friend and comrade, and with my feet together and my fingers spread over my heart, I say, in the language of Alabama, “You do me proud.”)

I stand guilty of the authorship of the article, but I did not mean any harm. I saw by an item in the Boston Advertiser that a solemn, serious critique on the English edition of my book had appeared in the London Saturday Review, and the idea of such a literary breakfast by a stolid, ponderous British ogre of the quill was too much for a naturally weak virtue, and I went home and burlesqued it—revelled in it, I may say. I never saw a copy of the real Saturday Review criticism until after my burlesque was written and mailed to the printer. But when I did get hold of a copy, I found it to be vulgar, awkwardly written, ill- natured, and entirely serious and in earnest. The gentleman who wrote the newspaper paragraph above quoted had not been misled as to its character.

If any man doubts my word now, I will kill him. No, I will not kill him; I will win his money. I will bet him twenty to one, and let any New York publisher hold the stakes, that the statements I have above made as to the authorship of the article in question are entirely true. Perhaps I may get wealthy at this, for I am willing to take all the bets that offer; and if a man wants larger odds, I will give him all he requires. But he ought to find out whether I am betting on what is termed “a sure thing” or not before he ventures his money, and he can do that by going to a public library and examining the London Saturday Review of October 8th, which contains the real critique.

Bless me, some people thought that I was the “sold” person!

P. S.—I cannot resist the temptation to toss in this most savory thing of all—this easy, graceful, philosophical disquisition, with its happy, chirping confidence. It is from the Cincinnati Enquirer:

“Nothing is more uncertain than the value of a fine cigar. Nine smokers out of ten would prefer an ordinary domestic article, three for a quarter, to a fifty-cent Partaga, if kept in ignorance of the cost of the latter. The flavor of the Partaga is too delicate for palates that have been accustomed to Connecticut seed leaf. So it is with humor. The finer it is in quality, the more danger of its not being recognized at all. Even Mark Twain has been taken in by an English review of his Innocents Abroad. Mark Twain is by no means a coarse humorist, but the Englishman’s humor is so much finer than his, that he mistakes it for solid earnest, and ‘larfs most consumedly.’ ”

A man who cannot learn stands in his own light. Hereafter, when I write an article which I know to be good, but which I may have reason to fear will not, in some quarters, be considered to amount to much, coming from an American, I will aver that an Englishman wrote it and that it is copied from a London journal. And then I will occupy a back seat and enjoy the cordial applause.

(Still later)

“Mark Twain at last sees that the Saturday Review’s criticism of his Innocents Abroad was not serious, and he is intensely mortified at the thought of having been so badly sold. He takes the only course left him, and in the last Galaxy claims that he wrote the criticism himself, and published it in The Galaxy to sell the public. This is ingenious, but unfortunately it is not true. If any of our readers will take the trouble to call at this office we will show them the original article in the Saturday Review of October 8th, which, on comparison, will be found to be identical with the one published in The Galaxy. The best thing for Mark to do will be to admit that he was sold, and say no more about it.”

The above is from the Cincinnati Enquirer, and is a falsehood. Come to the proof. If the Enquirer people, through any agent, will produce at The Galaxy office a London Saturday Review of October 8th, containing an “article which, on comparison, will be found to be that identical with the one published in The Galaxy, I will pay to that agent five hundred dollars cash. Moreover, if at any specified time I fail to produce at the same place a copy of the London Saturday Review of October 8th, containing a lengthy criticism upon the Innocents Abroad, entirely different, in every paragraph and sentence, from the one I published in The Galaxy, I will pay to the Enquirer agent another five hundred dollars cash. I offer Sheldon & Co., publishers, 500 Broadway, New York, as my “backers.” Any one in New York, authorized by the Enquirer, will receive prompt attention. It is an easy and profitable way for the Enquirer people to prove that they have not uttered a pitiful, deliberate falsehood in the above paragraphs. Will they swallow that falsehood ignominiously, or will they send an agent to The Galaxy office? I think the Cincinnati Enquirer must be edited by children.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

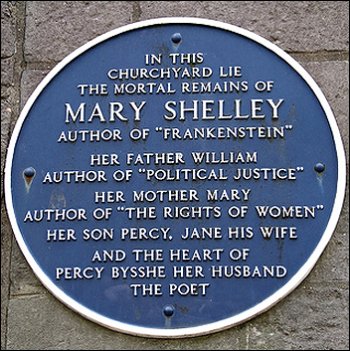

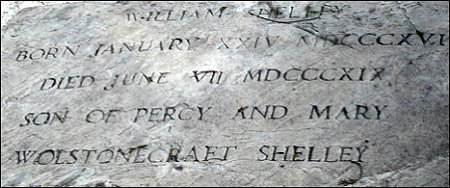

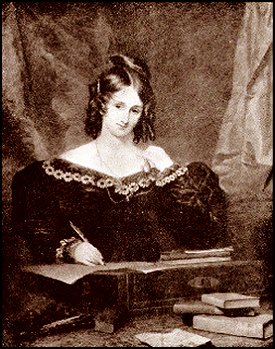

Percy Bysshe Shelley

(August 4, 1792 Horsham, England – July 8, 1822 Livorno, Italy)

Nine Poems

Death

1

They die–the dead return not–Misery

Sits near an open grave and calls them over,

A Youth with hoary hair and haggard eye–

They are the names of kindred, friend and lover,

Which he so feebly calls–they all are gone–

Fond wretch, all dead! those vacant names alone,

This most familiar scene, my pain–

These tombs–alone remain.

2

Misery, my sweetest friend–oh, weep no more!

Thou wilt not be consoled–I wonder not!

For I have seen thee from thy dwelling’s door

Watch the calm sunset with them, and this spot

Was even as bright and calm, but transitory,

And now thy hopes are gone, thy hair is hoary;

This most familiar scene, my pain–

These tombs–alone remain.

Satan broken loose

(fragment)

A golden-winged Angel stood

Before the Eternal Judgement-seat:

His looks were wild, and Devils’ blood

Stained his dainty hands and feet.

The Father and the Son

Knew that strife was now begun.

They knew that Satan had broken his chain,

And with millions of daemons in his train,

Was ranging over the world again.

Before the Angel had told his tale,

A sweet and a creeping sound

Like the rushing of wings was heard around;

And suddenly the lamps grew pale–

The lamps, before the Archangels seven,

That burn continually in Heaven.

Lines to a critic

1

Honey from silkworms who can gather,

Or silk from the yellow bee?

The grass may grow in winter weather

As soon as hate in me.

2

Hate men who cant, and men who pray,

And men who rail like thee;

An equal passion to repay

They are not coy like me.

3

Or seek some slave of power and gold

To be thy dear heart’s mate;

Thy love will move that bigot cold

Sooner than me, thy hate.

4

A passion like the one I prove

Cannot divided be;

I hate thy want of truth and love–

How should I then hate thee?

To…?

1

I fear thy kisses, gentle maiden,

Thou needest not fear mine;

My spirit is too deeply laden

Ever to burthen thine.

2

I fear thy mien, thy tones, thy motion,

Thou needest not fear mine;

Innocent is the heart’s devotion

With which I worship thine.

Song of Proserpine while gathering flowers

on the Plain of Enna

1

Sacred Goddess, Mother Earth,

Thou from whose immortal bosom

Gods, and men, and beasts have birth,

Leaf and blade, and bud and blossom,

Breathe thine influence most divine

On thine own child, Proserpine.

2

If with mists of evening dew

Thou dost nourish these young flowers

Till they grow, in scent and hue,

Fairest children of the Hours,

Breathe thine influence most divine

On thine own child, Proserpine.

Autumn: A Dirge

1

The warm sun is failing, the bleak wind is wailing,

The bare boughs are sighing, the pale flowers are dying,

And the Year

On the earth her death-bed, in a shroud of leaves dead,

Is lying.

Come, Months, come away,

From November to May,

In your saddest array;

Follow the bier

Of the dead cold Year,

And like dim shadows watch by her sepulchre.

2

The chill rain is falling, the nipped worm is crawling,

The rivers are swelling, the thunder is knelling

For the Year;

The blithe swallows are flown, and the lizards each gone

To his dwelling;

Come, Months, come away;

Put on white, black, and gray;

Let your light sisters play–

Ye, follow the bier

Of the dead cold Year,

And make her grave green with tear on tear.

Death

1

Death is here and death is there,

Death is busy everywhere,

All around, within, beneath,

Above is death–and we are death.

2

Death has set his mark and seal

On all we are and all we feel,

On all we know and all we fear,

3

First our pleasures die–and then

Our hopes, and then our fears–and when

These are dead, the debt is due,

Dust claims dust–and we die too.

4

All things that we love and cherish,

Like ourselves must fade and perish;

Such is our rude mortal lot–

Love itself would, did they not.

To the moon

1

Art thou pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless

Among the stars that have a different birth,–

And ever changing, like a joyless eye

That finds no object worth its constancy?

2

Thou chosen sister of the Spirit,

That grazes on thee till in thee it pities…

Sonnet

Ye hasten to the grave! What seek ye there,

Ye restless thoughts and busy purposes

Of the idle brain, which the world’s livery wear?

O thou quick heart, which pantest to possess

All that pale Expectation feigneth fair!

Thou vainly curious mind which wouldest guess

Whence thou didst come, and whither thou must go,

And all that never yet was known would know–

Oh, whither hasten ye, that thus ye press,

With such swift feet life’s green and pleasant path,

Seeking, alike from happiness and woe,

A refuge in the cavern of gray death?

O heart, and mind, and thoughts! what thing do you

Hope to inherit in the grave below?

Percy Bysshe Shelley: Nine Poems

• fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Percy Byssche Shelley, Shelley, Percy Byssche

V e r z a m e l e n

door Ed Schilders

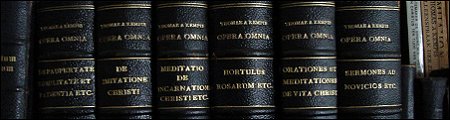

Het is slechts toeval dat mijnheer Van Kempen dezelfde achternaam heeft als de schrijver wiens boek hij verzamelt, Thomas van Kempen en diens ‘Navolging van Christus’. ‘Wij zijn geen familie’, zei hij, en ik begreep dat hij niet Christus maar Thomas bedoelde. En hij toonde mij alle honderd verschillende uitgaven, die hij in de loop der jaren verzameld had. Dat zijn collectie nog lang niet compleet was, wist hij, maar hij vond het niet erg; een complete collectie is immers het ergste dat de boekverzamelaar kan overkomen.

Ik vond het mooi om te zien, die honderd verschillende ‘Navolgingen’, een processie van gedrukte gelovigheid, onveranderd door de eeuwen. Ik heb het nooit gelezen, maar ik waardeer Thomas om het gevleugeld geworden woord dat hij onder zijn beeltenis liet schrijven: ‘Met een boeksken in een hoeksken.’

Ook dat is nooit meer veranderd.

Nu heeft zich kortelings aan mijnheer Van Kempen iets ernstigs voltrokken.

Hij kreeg een erfenis. In een bibliotheek die meer religieuze werken bezit dan God er gelezen heeft, kwam een kaartenbak te overlijden. De bibliothecaris sprak mij aan dat het kaartsysteem over Thomas van Kempen, na een flink gedragen ziekbed, toch nog schielijk het papieren leven verwisseld had voor het digitale hiernamaals. Ik zag een traan in zijn ooghoek, ik troostte hem. Toen dacht ik aan meneer Van Kempen als erfgenaam.

Van Kempen zit sindsdien stilletjes in het hoekske van zijn bibliotheek. Het kaartsysteem staat op het tafeltje: tweeduizend en meer verschillende uitgaven van ‘De navolging’. Aan hem heeft zich het ergste geopenbaard dat een verzamelaar kan treffen: het besef dat er geen eind is aan het verzamelen van boeken. Hij zegt: ‘Je wordt er nederig van, dat wel.’

(de Volkskrant van 29-05-1997, Pagina 29, column CICERO)

Ed Schilders over Thomas a Kempis

© Schilders, E.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, BOOKS. The final chapter?, Ed Schilders, Jef van Kempen, MONTAIGNE, Thomas a Kempis

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature