Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Deutschland 1940: Max Koenig ist Professor für Altertumsforschung. Ein vererbtes Nervenleiden reißt ihn aus seinem beruflichen Leben und fort von seiner Familie.

Er kommt in die Wittenauer Heilstätten und trifft dort auf Schwester Rosemarie, die versucht zu helfen, wo sie kann. Trotz seiner Hinfälligkeit wird Koenig zum Mittelpunkt einer kleinen Gruppe: dem Studienrat Dr. Carl Hohein, der eine Litanei auf die Farbe »Schwarz« komponiert, der jungen Pianistin Elfie, deren Hände zittern und die »Traumdeutsch« spricht, und schließlich Oscar, einem Jungen mit Trisomie 21.

Er kommt in die Wittenauer Heilstätten und trifft dort auf Schwester Rosemarie, die versucht zu helfen, wo sie kann. Trotz seiner Hinfälligkeit wird Koenig zum Mittelpunkt einer kleinen Gruppe: dem Studienrat Dr. Carl Hohein, der eine Litanei auf die Farbe »Schwarz« komponiert, der jungen Pianistin Elfie, deren Hände zittern und die »Traumdeutsch« spricht, und schließlich Oscar, einem Jungen mit Trisomie 21.

Der Alltag auf der Station, die mangelhaften Essensrationen und die rassenhygienischen Kommentare der medizinischen »Spezialisten« werden nur durch die gegenseitige Unterstützung und kleine Freuden, wie die Besuche von Frau und Schwägerin, erträglich. Sie hoffen darauf, sich nach dem Krieg im Traumland Italien wiederzufinden. Doch Max Koenig und Oscar werden verlegt und ihren Angehörigen entzogen.

Töten wird sie Dr. Friedel Lerbe, ein Arzt, SS-Mann und fanatischer Verfechter der Rassenhygiene. Als Leiter einer Tötungsanstalt führt er das NS-»Euthanasie«-Programm mit bürokratischer Präzision aus – jedes Detail des Ablaufs wird von ihm kontrolliert. Ein ganzer Stab von »Pflegern«, Sekretärinnen, Technikern und Leichenbrennern steht diesem »Spezialisten« bei seinem Handwerk zur Seite.

Barbara Zoeke schildert das Geschehen aus unterschiedlichen Perspektiven – empathisch und erschütternd klar. Es gelingt ihr, dieses Verbrechen der Nationalsozialisten zu vergegenwärtigen und den Opfern, Angehörigen und Tätern eine literarische Stimme zu geben.

Barbara Zoeke schildert das Geschehen aus unterschiedlichen Perspektiven – empathisch und erschütternd klar. Es gelingt ihr, dieses Verbrechen der Nationalsozialisten zu vergegenwärtigen und den Opfern, Angehörigen und Tätern eine literarische Stimme zu geben.

Barbara Zoeke erhält für ihren Roman „Die Stunde der Spezialisten“ den Brüder-Grimm-Preis 2017 der Stadt Hanau!

Die Preisverleihung findet am 17. November in der Hanauer Stadtbibliothek/Kulturforum Hanau statt. Die Laudatio auf die Preisträgerin wird der Literatur-Chef der Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung Andreas Platthaus halten. Die Auszeichnung ist mit 10.000 Euro dotiert.

Die Jury mit Literaturkritikerin Dr. Insa Wilke, Literaturprofessor Professor Dr. Heiner Boehncke und dem ehemaligen Vorsitzenden des hessischen Bibliotheksverbandes Aloys Lenz MdL a.D. votierte nach eingehender Diskussion der eingereichten Veröffentlichungen einstimmig für das kürzlich im Verlag „Die Andere Bibliothek“ erschienene Buch. Der Magistrat der Stadt Hanau schloss sich einmütig dem Votum der Jury an.

Aus der Jury-Entscheidung:

„Barbara Zoekes Roman „Die Stunde der Spezialisten“ widmet sich einem in der deutschsprachigen Literatur immer noch auffällig selten erzählten Verbrechen der Nationalsozialisten: der Ermordung von Psychiatriepatienten und Behinderten, allgemein unter dem Euphemismus  „Euthanasie“ bekannt. Autorinnen wie Olga Martynova und entfernt auch Angela Steidele haben sich zuletzt mit diesem Stoff auseinandergesetzt; Barbara Zoeke ist jedoch die erste Autorin, die wohl auch aufgrund ihrer psychiatrischen Praxis die besondere Sprache der Patienten in eine literarische verwandelt und ihnen so auf besondere Weise ein Denkmal setzt. Virtuos komponiert sie auf diese Weise aus den Stimmen der Opfer wie auch der Täter in je spezifischen Sprechweisen ein beklemmendes Kunstwerk in humanistischen Traditionen, das bei seinen Leserinnen und Lesern für einen inneren Aufruhr sorgt, wie ihn nur hervorragende literarische Werke hervorzubringen imstande sind. Die Jury sieht in der meisterlichen Sprache des Romans und dem sensiblen Umgang mit den unterschiedlichen Stimmen überdies eine Nähe zu dem Werk der Brüder Grimm, das sich auf der Grenze zwischen Archiv, Sprachforschung und Erzählen bewegt.“

„Euthanasie“ bekannt. Autorinnen wie Olga Martynova und entfernt auch Angela Steidele haben sich zuletzt mit diesem Stoff auseinandergesetzt; Barbara Zoeke ist jedoch die erste Autorin, die wohl auch aufgrund ihrer psychiatrischen Praxis die besondere Sprache der Patienten in eine literarische verwandelt und ihnen so auf besondere Weise ein Denkmal setzt. Virtuos komponiert sie auf diese Weise aus den Stimmen der Opfer wie auch der Täter in je spezifischen Sprechweisen ein beklemmendes Kunstwerk in humanistischen Traditionen, das bei seinen Leserinnen und Lesern für einen inneren Aufruhr sorgt, wie ihn nur hervorragende literarische Werke hervorzubringen imstande sind. Die Jury sieht in der meisterlichen Sprache des Romans und dem sensiblen Umgang mit den unterschiedlichen Stimmen überdies eine Nähe zu dem Werk der Brüder Grimm, das sich auf der Grenze zwischen Archiv, Sprachforschung und Erzählen bewegt.“

Dr. Barbara Zoeke verbrachte ihre Kindheit im thüringischen Vogtland und studierte in Köln und Münster. Sie ist habilitierte Psychologin, forschte in den USA und war über mehrere Jahre im Vorstand der “International Society of Comparative Psychology”. Sie lehrte und forschte an den Universitäten von Münster, Frankfurt, Würzburg und München. Neben wissenschaftlichen Arbeiten zur Wahrnehmung und zum Gedächtnis veröffentlichte sie erzählende Prosa, Lyrik und Sachbuchtexte. Die Autorin lebt seit 2008 in Berlin.

Barbara Zoeke

Die Stunde der Spezialisten

Seitenanzahl: 300

Originalausgaben

Bandnummer: 393

Originalausgabe,

nummeriert und limitiert

Gestaltung: Lars Henkel.

Kunstvolle Collagen für Cover,

Bezug, Vor- und Nachsatzpapier.

Fadenheftung, Lesebändchen.

ISBN: 9783847703938

2017 – 42,00 EUR

Die Andere Bibliothek

10969 Berlin

# website die andere bibliothek

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive Y-Z, Art & Literature News, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, WAR & PEACE

Hans Christian Andersen: ‘Beautiful’

Alfred the sculptor – yes, you know him, don’t you? We all know him; he was awarded the gold medal, traveled to Italy, and came home again. He was young then; in fact, he is still young, though he is ten years older than he was at that time.

After he returned home, he visited one of the little provincial towns on the island of Zealand. The whole village knew who the stranger was, and in his honor one of the richest families gave a party. Everyone of any importance or owning any property was invited. It was quite an event, and all the village knew about it without its being announced by the town crier. Apprentice boys and the children of poor people, and even some of their parents, stood outside the house, looking at the lighted windows with their drawn curtains; and the watchman could imagine that he was giving the party, there were so many people in his street. There was an air of festivity everywhere, and inside the house, too, for Mr. Alfred the sculptor was there.

He talked and told stories, and everybody listened to him with pleasure and enthusiasm, but none more so than the elderly widow of a state official. As far as Mr. Alfred was concerned, she was like a blank sheet of gray blotting paper, absorbing everything that was said and demanding more. She was highly susceptible and unbelievably ignorant-a sort of female Kaspar Hauser.

“I should love to see Rome!” she said. “It must be a wonderful city, with all the many strangers continually arriving there. Now, do tell us what Rome is like. How does the city look when you come in by the gate?”

“It is not easy to describe it,” said the young sculptor. “There’s a great open place, and in the middle of it there is an obelisk that is four thousand years old.”

“An organist!” cried the lady, who had never heard the word “obelisk.”

Some of the guests could hardly keep from laughing, among them the sculptor, but the smile that rose to his lips quickly faded away, for he saw, close by the lady, a pair of dark-blue eyes; they belonged to the daughter of the lady who had been talking, and anyone with such a daughter could not really be silly! The mother was like a fountain of questions, and the daughter, who listened silently, might pass for the naiad of the fountain. How beautiful she was! She was something for a sculptor to look at, but not to speak with, for indeed she talked but very little.

“Has the Pope a large family?” asked the lady.

And the young man answered considerately, as if the question had been put differently, “No, he doesn’t come of a very great family.”

“That’s not what I mean,” said the lady. “I mean, does he have a wife and children?”

“The Pope isn’t allowed to marry,” he replied.

“I don’t approve of that,” said the lady.

She might well have talked and questioned him more intelligently, but if she hadn’t said and asked what she did, would her daughter have leaned so gracefully on her shoulder, looking straight before her with an almost melancholy smile on her lips?

And Mr. Alfred told them of the glorious colors of Italy, the purple of the mountains, the blue of the Mediterranean, the blue of the southern skies, a beauty that could only be surpassed in the North by the deep-blue eyes of a maiden. This he said with peculiar meaning, but she who should have understood it looked quite unconscious, and that, too, was charming!

“Ah, Italy!” sighed some of the guests.

“Traveling!” sighed others.

“Charming, charming!”

“Well,” said the widow, “if I win fifty thousand dollars in the lottery, we’ll travel! My daughter and I. You Mr. Alfred, must be our guide. We’ll all three go, with just one or two good friends with us.” Then she smiled in such a friendly manner at the company that each of them could imagine he was the person who would accompany them to Italy. “Yes, we’ll go to Italy! But not to the parts where the robbers are; we’ll stay in Rome and only travel by the great highways where we’ll be safe.”

And the daughter sighed very gently. And how much may lie in one little sigh or be read into it! The young man read a great deal into it. Those two blue eyes, bright that evening in his honor, must conceal treasures of heart and mind rarer than all the glories of Rome! When he left the party, he had lost his heart-lost it completely-to the young lady.

Now, the widow’s house was where Mr. Alfred the sculptor could most frequently be found. It was understood that his calls were not for the lady herself, though he and she did all the talking; he really came for the sake of the daughter. They called her Kala. Her real name was Karen Malene, but the two names had been contracted into the single name Kala. She was extremely, but some people said she was rather dull and probably slept late in the mornings.

“She has been accustomed to that since childhood,” said her mother. “She is as beautiful as Venus, and a beauty always tires easily. She does sleep rather late, but that’s what makes her eyes so bright.”

What a power there was in these clear eyes, these deep blue eyes! “Still waters run deep.” The young man felt the truth of that proverb, and his heart sank into the depths. He spoke of his adventures, and Mamma always asked the same naïve and pertinent questions she had asked at their first meeting.

It was a delight to hear Mr. Alfred speak. He told them of Naples, of trips to Mount Vesuvius, and showed them colored prints of some of the eruptions. The widow had never heard of such things before, much less taken time to think about them.

“Mercy save us!” she said. “So that’s a burning mountain! But isn’t it dangerous for the people who live there?”

“Entire cities have been destroyed,” he answered. “For example, Pompeii and Herculaneum.”

“Oh, the poor people! And you saw all that yourself?”

“Well, no, I didn’t see any of the eruptions shown in these pictures, but I’ll show you a drawing I made of an eruption I did see.”

He laid a pencil sketch on the table, and when Mamma, who had been studying the highly colored prints, glanced at the black-and-white drawing, she cried in amazement, “When you saw it did it throw up white fire?”

For a moment Alfred’s respect for Kala’s mamma nearly vanished; but then, dazzled by the light from Kala, he decided it was natural for the old lady to have no eye for color. After all, it didn’t matter, for Kala’s mamma had the most wonderful thing of all-she had Kala herself.

And Alfred and Kala were engaged, which was inevitable, and the engagement was announced in the town newspaper. Mamma brought thirty copies of the paper, so she could cut out the announcement and send it to her friends. The betrothed couple were happy, and the mamma-in-law-to-be was happy, too; she said it seemed like being related to Thorvaldsen himself.

“At any rate, you are his successor,” she told Alfred.

And it seemed to Alfred that Mamma had this time really said something clever. Kala said nothing, but her eyes sparkled; her every gesture was graceful. Yes, she was beautiful; that cannot be repeated too often.

Alfred made busts of Kala and his future mamma-in-law; they sat for him and watched how he molded and smoothed the soft clay between his fingers.

“I suppose it’s only for us that you do this common work,” said Mamma-in-law-to-be, “and don’t have your servant do all that dabbing together.”

“No, I have to mold the clay myself,” he explained.

“Oh, yes, you’re always so exceedingly polite,” said Mamma, while Kala silently pressed his hand, still soiled by the clay.

Then he unfolded to both of them the loveliness of nature in creation, explaining how the living stood higher in the scale than the dead, how the plant was above the mineral, the animal above the plant, and man above the animal, how mind and beauty are united in outward form, and how it was the task of the sculptor to seize that beauty and imprison it in his works.

Kala sat silent and nodded approval of the thought, while Mamma-in-law confessed, “It’s hard to follow all that. But my thoughts manage to hobble slowly along after you; they whirl around, but I try to hold them fast.”

And the power of Kala’s beauty held Alfred fast, seizing him and mastering him and filling his whole soul. There was beauty in Kala’s every feature; it sparkled in her eyes, lurked in the corners of her mouth and even in each movement of her fingers. The sculptor saw this; he spoke only of her, thought only of her, until the two became one. Thus it might be said that she also spoke often, for he was always talking of her, and they two were one.

Such was the betrothal; and now came the wedding day, with bridesmaids and presents, all duly mentioned in the wedding speech.

Mamma-in-law had set up a bust of Thorvaldsen, attired in a dressing gown, at one end of the table, for it was her whim that he was to be a guest. There were songs and toasts, for it was a gay wedding and they were a handsome pair. “Pygmalion gets his Galatea,” one of the songs said.

“That is something from mythology!” said Mamma-in-law.

Next day the young couple left for Copenhagen, where they were to live. Mamma-in-law went with them, “to give them a helping hand,” she explained-which meant to take charge of the house. Kala was to live in a doll’s house. Everything was so bright, new, and fine. There the three of them sat, and as for Alfred, to use a proverb that describes his circumstances, he sat like the bishop in the goose yard.

The magic of form had fascinated him. He had regarded the case and had no interest in learning what the case contained, and that is unfortunate, very unfortunate, in married life! If the case breaks and the gilding rubs off, the purchaser may repent of his bargain. It is very embarrassing to discover in a large party that one’s suspender buttons are coming off and that one has no belt to fall back on; but it is still worse to realize at a great party that one’s wife and mother-in-law are talking nonsense and that one cannot think of a clever piece of wit to cover up the stupidity of it.

The young couple often sat hand in hand, he speaking and she letting drop a word now and then-with always the same melody, like a clock striking the same two or three notes constantly. It was really a mental relief when one of her friends, Sophie, came to visit them.

Sophie wasn’t pretty. To be sure, she was not deformed; Kala always said she was a little crooked, but no one but a female friend would have noticed that. She was a very levelheaded girl and had no idea that she might ever become dangerous here. Her visits brought a fresh breath of air into the doll’s house, air that they all agreed was certainly needed there. But they felt they needed more airing, so they came out into the air, and Mamma-in-law and the young couple traveled to Italy.

“Thank heaven we are back in our own home again!” said both mother and daughter when they and Alfred returned home a year later.

“Traveling is no fun,” said Mamma-in-law. “On the contrary, it’s very tiring; pardon me for saying so. I found the time dragged, even though I had my children with me; and it is expensive, very expensive, to travel. All those galleries you have to see, and all the things you have to look at! You must do it for self-protection, because when you get back people are sure to ask you about them; and then they’re sure to tell you that you’ve missed the most worth-while things. I got so tired at last of those everlasting Madonnas; I thought I would turn into a Madonna myself!”

“And the food one gets!” said Kala.

“Yes,” agreed Mamma. “Not even a dish of honest meat soup! It is awful the way they cook!”

And Kala had become tired from traveling; she was always tired; that was the trouble. Sophie came to live with them, and her presence was a real help.

Mamma-in-law had to admit that Sophie understood both housekeeping and art, though you would hardly have expected a knowledge of the last from a person of her modest background. Moreover, she was honest and loyal; she showed that clearly when Kala lay sick, fading away.

If the case is everything, that case should be strong, or it is all over. And it was all over with the case-Kala died.

“She was so beautiful,” said Mamma. “She was very different from the antiques, because they’re all so damaged. Kala was completely perfect, just as a beauty should be.”

Alfred wept and the Mother wept, and both went into mourning. The black dresses became Mamma very well, so she wore her mourning the longer. Moreover, she soon experienced another grief, when she saw Alfred marry again. And he married Sophie, who had no looks at all!

“He has gone from one extreme to the other!” said Mamma-in-law. “Gone from the most beautiful to the ugliest! How could he forget his first wife! Men have no constancy. Now, my husband was entirely different, and he died before I did.”

“Pygmalion got his Galatea,” said Alfred. “Yes, that’s what the wedding song said. I really fell in love with a beautiful statue, which came to life in my arms, but the soul mate that heaven sends down to us, one of its angels who can comfort and sympathize with and uplift us, I have not found or won till now. You came to me, Sophie, not in the glory of superficial beauty – but fair enough, prettier than was necessary. The most important thing is still the most important. You came to teach a sculptor that his work is only clay and dust, only the outward form in a fabric that passes away, and that we must seek the spirit within. Poor Kala! Ours was but a wayfarer’s life. In the next world, where we shall come together through sympathy, we shall probably be half strangers to each other.

“That was not spoken kindly,” said Sophie, ” not like a true Christian. In the next world, where there is no marriage, but where, as you say, souls find each other through sympathy, where everything beautiful is developed and elevated, her soul may attain such completeness that it may resound far more melodiously than mine. Then you will again utter the first exciting cry of your love, ‘Beautiful, beautiful!'”

END

Hans Christian Andersen (1805—1875) fairy tales and stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andersen, Andersen, Hans Christian, Archive A-B, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Hans Christian Andersen

(1805—1875)

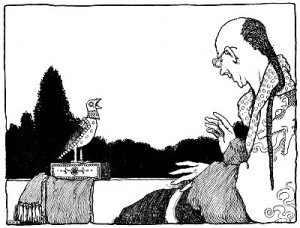

The nightingale

In China, you know, the emperor is a Chinese, and all those about him are Chinamen also. The story I am going t tell you happened a great many years ago, so it is well to hear it now before it is forgotten. The emperor’s palac was the most beautiful in the world. It was built entirely of porcelain, and very costly, but so delicate and brittle tha whoever touched it was obliged to be careful. In the garden could be seen the most singular flowers, with prett silver bells tied to them, which tinkled so that every one who passed could not help noticing the flowers.

Indeed everything in the emperor’s garden was remarkable, and it extended so far that the gardener himself did not kno where it ended. Those who travelled beyond its limits knew that there was a noble forest, with lofty trees, slopin down to the deep blue sea, and the great ships sailed under the shadow of its branches. In one of these trees live a nightingale, who sang so beautifully that even the poor fishermen, who had so many other things to do, woul stop and listen. Sometimes, when they went at night to spread their nets, they would hear her sing, and say, “Oh, i not that beautiful?” But when they returned to their fishing, they forgot the bird until the next night. Then they woul hear it again, and exclaim “Oh, how beautiful is the nightingale’s song!

Travellers from every country in the world came to the city of the emperor, which they admired very much, as well as the palace and gardens; but when they heard the nightingale, they all declared it to be the best of all.

And the travellers, on their return home, related what they had seen; and learned men wrote books, containing descriptions of the town, the palace, and the gardens; but they did not forget the nightingale, which was really the greatest wonder. And those who could write poetry composed beautiful verses about the nightingale, who lived in a forest near the deep sea.

The books travelled all over the world, and some of them came into the hands of the emperor; and he sat in his golden chair, and, as he read, he nodded his approval every moment, for it pleased him to find such a beautiful description of his city, his palace, and his gardens. But when he came to the words, “the nightingale is the most beautiful of all,” he exclaimed:

“What is this? I know nothing of any nightingale. Is there such a bird in my empire? and even in my garden? I have never heard of it. Something, it appears, may be learnt from books.”

Then he called one of his lords-in-waiting, who was so high-bred, that when any in an inferior rank to himself spoke to him, or asked him a question, he would answer, “Pooh,” which means nothing.

“There is a very wonderful bird mentioned here, called a nightingale,” said the emperor; “they say it is the best thing in my large kingdom. Why have I not been told of it?”

“I have never heard the name,” replied the cavalier; “she has not been presented at court.”

“It is my pleasure that she shall appear this evening.” said the emperor; “the whole world knows what I possess better than I do myself.”

“I have never heard of her,” said the cavalier; “yet I will endeavor to find her.”

But where was the nightingale to be found? The nobleman went up stairs and down, through halls and passages; yet none of those whom he met had heard of the bird. So he returned to the emperor, and said that it must be a fable, invented by those who had written the book. “Your imperial majesty,” said he, “cannot believe everything contained in books; sometimes they are only fiction, or what is called the black art.”

“But the book in which I have read this account,” said the emperor, “was sent to me by the great and mighty emperor of Japan, and therefore it cannot contain a falsehood. I will hear the nightingale, she must be here this evening; she has my highest favor; and if she does not come, the whole court shall be trampled upon after supper is ended.”

“Tsing-pe!” cried the lord-in-waiting, and again he ran up and down stairs, through all the halls and corridors; and half the court ran with him, for they did not like the idea of being trampled upon. There was a great inquiry about this wonderful nightingale, whom all the world knew, but who was unknown to the court.

At last they met with a poor little girl in the kitchen, who said, “Oh, yes, I know the nightingale quite well; indeed, she can sing. Every evening I have permission to take home to my poor sick mother the scraps from the table; she lives down by the sea-shore, and as I come back I feel tired, and I sit down in the wood to rest, and listen to the nightingale’s song. Then the tears come into my eyes, and it is just as if my mother kissed me.”

“Little maiden,” said the lord-in-waiting, “I will obtain for you constant employment in the kitchen, and you shall have permission to see the emperor dine, if you will lead us to the nightingale; for she is invited for this evening to the palace.”

So she went into the wood where the nightingale sang, and half the court followed her. As they went along, a cow began lowing.

“Oh,” said a young courtier, “now we have found her; what wonderful power for such a small creature; I have certainly heard it before.”

“No, that is only a cow lowing,” said the little girl; “we are a long way from the place yet.”

Then some frogs began to croak in the marsh.

“Beautiful,” said the young courtier again. “Now I hear it, tinkling like little church bells.”

“No, those are frogs,” said the little maiden; “but I think we shall soon hear her now:”

And presently the nightingale began to sing.

“Hark, hark! there she is,” said the girl, “and there she sits,” she added, pointing to a little gray bird who was perched on a bough.

“Is it possible?” said the lord-in-waiting, “I never imagined it would be a little, plain, simple thing like that. She has certainly changed color at seeing so many grand people around her.”

“Little nightingale,” cried the girl, raising her voice, “our most gracious emperor wishes you to sing before him.”

“With the greatest pleasure,” said the nightingale, and began to sing most delightfully.

“It sounds like tiny glass bells,” said the lord-in-waiting, “and see how her little throat works. It is surprising that we have never heard this before; she will be a great success at court.”

“Shall I sing once more before the emperor?” asked the nightingale, who thought he was present.

“My excellent little nightingale,” said the courtier, “I have the great pleasure of inviting you to a court festival this evening, where you will gain imperial favor by your charming song.”

“My song sounds best in the green wood,” said the bird; but still she came willingly when she heard the emperor’s wish.

The palace was elegantly decorated for the occasion. The walls and floors of porcelain glittered in the light of a thousand lamps. Beautiful flowers, round which little bells were tied, stood in the corridors: what with the running to and fro and the draught, these bells tinkled so loudly that no one could speak to be heard.

In the centre of the great hall, a golden perch had been fixed for the nightingale to sit on. The whole court was present, and the little kitchen-maid had received permission to stand by the door. She was not installed as a real court cook. All were in full dress, and every eye was turned to the little gray bird when the emperor nodded to her to begin.

The nightingale sang so sweetly that the tears came into the emperor’s eyes, and then rolled down his cheeks, as her song became still more touching and went to every one’s heart. The emperor was so delighted that he declared the nightingale should have his gold slipper to wear round her neck, but she declined the honor with thanks: she had been sufficiently rewarded already.

“I have seen tears in an emperor’s eyes,” she said, “that is my richest reward. An emperor’s tears have wonderful power, and are quite sufficient honor for me;” and then she sang again more enchantingly than ever.

“That singing is a lovely gift;” said the ladies of the court to each other; and then they took water in their mouths to make them utter the gurgling sounds of the nightingale when they spoke to any one, so thay they might fancy themselves nightingales. And the footmen and chambermaids also expressed their satisfaction, which is saying a great deal, for they are very difficult to please. In fact the nightingale’s visit was most successful.

She was now to remain at court, to have her own cage, with liberty to go out twice a day, and once during the night. Twelve servants were appointed to attend her on these occasions, who each held her by a silken string fastened to her leg. There was certainly not much pleasure in this kind of flying.

The whole city spoke of the wonderful bird, and when two people met, one said “nightin,” and the other said “gale,” and they understood what was meant, for nothing else was talked of. Eleven peddlers’ children were named after her, but not of them could sing a note.

One day the emperor received a large packet on which was written “The Nightingale.”

“Here is no doubt a new book about our celebrated bird,” said the emperor. But instead of a book, it was a work of art contained in a casket, an artificial nightingale made to look like a living one, and covered all over with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires. As soon as the artificial bird was wound up, it could sing like the real one, and could move its tail up and down, which sparkled with silver and gold. Round its neck hung a piece of ribbon, on which was written “The Emperor of China’s nightingale is poor compared with that of the Emperor of Japan’s.”

“This is very beautiful,” exclaimed all who saw it, and he who had brought the artificial bird received the title of “Imperial nightingale-bringer-in-chief.”

“Now they must sing together,” said the court, “and what a duet it will be.”

But they did not get on well, for the real nightingale sang in its own natural way, but the artificial bird sang only waltzes. “That is not a fault,” said the music-master, “it is quite perfect to my taste,” so then it had to sing alone, and was as successful as the real bird; besides, it was so much prettier to look at, for it sparkled like bracelets and breast-pins.

Thirty three times did it sing the same tunes without being tired; the people would gladly have heard it again, but the emperor said the living nightingale ought to sing something. But where was she? No one had noticed her when she flew out at the open window, back to her own green woods.

“What strange conduct,” said the emperor, when her flight had been discovered; and all the courtiers blamed her, and said she was a very ungrateful creature. “But we have the best bird after all,” said one, and then they would have the bird sing again, although it was the thirty-fourth time they had listened to the same piece, and even then they had not learnt it, for it was rather difficult. But the music-master praised the bird in the highest degree, and even asserted that it was better than a real nightingale, not only in its dress and the beautiful diamonds, but also in its musical power.

“For you must perceive, my chief lord and emperor, that with a real nightingale we can never tell what is going to be sung, but with this bird everything is settled. It can be opened and explained, so that people may understand how the waltzes are formed, and why one note follows upon another.”

“This is exactly what we think,” they all replied, and then the music-master received permission to exhibit the bird to the people on the following Sunday, and the emperor commanded that they should be present to hear it sing. When they heard it they were like people intoxicated; however it must have been with drinking tea, which is quite a Chinese custom. They all said “Oh!” and held up their forefingers and nodded, but a poor fisherman, who had heard the real nightingale, said, “it sounds prettily enough, and the melodies are all alike; yet there seems something wanting, I cannot exactly tell what.”

And after this the real nightingale was banished from the empire.

The artificial bird was placed on a silk cushion close to the emperor’s bed. The presents of gold and precious stones which had been received with it were round the bird, and it was now advanced to the title of “Little Imperial Toilet Singer,” and to the rank of No. 1 on the left hand; for the emperor considered the left side, on which the heart lies, as the most noble, and the heart of an emperor is in the same place as that of other people. The music-master wrote a work, in twenty-five volumes, about the artificial bird, which was very learned and very long, and full of the most difficult Chinese words; yet all the people said they had read it, and understood it, for fear of being thought stupid and having their bodies trampled upon.

So a year passed, and the emperor, the court, and all the other Chinese knew every little turn in the artificial bird’s song; and for that same reason it pleased them better. They could sing with the bird, which they often did. The street-boys sang, “Zi-zi-zi, cluck, cluck, cluck,” and the emperor himself could sing it also. It was really most amusing.

One evening, when the artificial bird was singing its best, and the emperor lay in bed listening to it, something inside the bird sounded “whizz.” Then a spring cracked. “Whir-r-r-r” went all the wheels, running round, and then the music stopped.

The emperor immediately sprang out of bed, and called for his physician; but what could he do? Then they sent for a watchmaker; and, after a great deal of talking and examination, the bird was put into something like order; but he said that it must be used very carefully, as the barrels were worn, and it would be impossible to put in new ones without injuring the music. Now there was great sorrow, as the bird could only be allowed to play once a year; and even that was dangerous for the works inside it. Then the music-master made a little speech, full of hard words, and declared that the bird was as good as ever; and, of course no one contradicted him.

Five years passed, and then a real grief came upon the land. The Chinese really were fond of their emperor, and he now lay so ill that he was not expected to live. Already a new emperor had been chosen and the people who stood in the street asked the lord-in-waiting how the old emperor was.

But he only said, “Pooh!” and shook his head.

Cold and pale lay the emperor in his royal bed; the whole court thought he was dead, and every one ran away to pay homage to his successor. The chamberlains went out to have a talk on the matter, and the ladies’-maids invited company to take coffee. Cloth had been laid down on the halls and passages, so that not a footstep should be heard, and all was silent and still. But the emperor was not yet dead, although he lay white and stiff on his gorgeous bed, with the long velvet curtains and heavy gold tassels. A window stood open, and the moon shone in upon the emperor and the artificial bird.

The poor emperor, finding he could scarcely breathe with a strange weight on his chest, opened his eyes, and saw Death sitting there. He had put on the emperor’s golden crown, and held in one hand his sword of state, and in the other his beautiful banner. All around the bed and peeping through the long velvet curtains, were a number of strange heads, some very ugly, and others lovely and gentle-looking. These were the emperor’s good and bad deeds, which stared him in the face now Death sat at his heart.

“Do you remember this?” “Do you recollect that?” they asked one after another, thus bringing to his remembrance circumstances that made the perspiration stand on his brow.

“I know nothing about it,” said the emperor. “Music! music!” he cried; “the large Chinese drum! that I may not hear what they say.”

But they still went on, and Death nodded like a Chinaman to all they said.

“Music! music!” shouted the emperor. “You little precious golden bird, sing, pray sing! I have given you gold and costly presents; I have even hung my golden slipper round your neck. Sing! sing!”

But the bird remained silent. There was no one to wind it up, and therefore it could not sing a note. Death continued to stare at the emperor with his cold, hollow eyes, and the room was fearfully still.

Suddenly there came through the open window the sound of sweet music. Outside, on the bough of a tree, sat the living nightingale. She had heard of the emperor’s illness, and was therefore come to sing to him of hope and trust. And as she sung, the shadows grew paler and paler; the blood in the emperor’s veins flowed more rapidly, and gave life to his weak limbs; and even Death himself listened, and said, “Go on, little nightingale, go on.”

“Then will you give me the beautiful golden sword and that rich banner? and will you give me the emperor’s crown?” said the bird.

So Death gave up each of these treasures for a song; and the nightingale continued her singing. She sung of the quiet churchyard, where the white roses grow, where the elder-tree wafts its perfume on the breeze, and the fresh, sweet grass is moistened by the mourners’ tears. Then Death longed to go and see his garden, and floated out through the window in the form of a cold, white mist.

“Thanks, thanks, you heavenly little bird. I know you well. I banished you from my kingdom once, and yet you have charmed away the evil faces from my bed, and banished Death from my heart, with your sweet song. How can I reward you?”

“You have already rewarded me,” said the nightingale. “I shall never forget that I drew tears from your eyes the first time I sang to you. These are the jewels that rejoice a singer’s heart. But now sleep, and grow strong and well again. I will sing to you again.”

And as she sung, the emperor fell into a sweet sleep; and how mild and refreshing that slumber was!

When he awoke, strengthened and restored, the sun shone brightly through the window; but not one of his servants had returned– they all believed he was dead; only the nightingale still sat beside him, and sang.

“You must always remain with me,” said the emperor. “You shall sing only when it pleases you; and I will break the artificial bird into a thousand pieces.”

“No; do not do that,” replied the nightingale; “the bird did very well as long as it could. Keep it here still. I cannot live in the palace, and build my nest; but let me come when I like. I will sit on a bough outside your window, in the evening, and sing to you, so that you may be happy, and have thoughts full of joy. I will sing to you of those who are happy, and those who suffer; of the good and the evil, who are hidden around you. The little singing bird flies far from you and your court to the home of the fisherman and the peasant’s cot. I love your heart better than your crown; and yet something holy lingers round that also. I will come, I will sing to you; but you must promise me one thing.”

“Everything,” said the emperor, who, having dressed himself in his imperial robes, stood with the hand that held the heavy golden sword pressed to his heart.

“I only ask one thing,” she replied; “let no one know that you have a little bird who tells you everything. It will be best to conceal it.”

So saying, the nightingale flew away.

The servants now came in to look after the dead emperor; when, lo! there he stood, and, to their astonishment, said, “Good morning.”

END

Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales and stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andersen, Andersen, Hans Christian, Archive A-B, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm ♦ Rumpelstiltskin ♦ There was once a miller who was poor, but he had one beautiful daughter. It happened one day that he came to speak with the king, and, to give himself consequence, he told him that he had a daughter who could spin gold out of straw. The king said to the miller, “That is an art that pleases me well; if thy daughter is as clever as you say, bring her to my castle to-morrow, that I may put her to the proof.”

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm ♦ Rumpelstiltskin ♦ There was once a miller who was poor, but he had one beautiful daughter. It happened one day that he came to speak with the king, and, to give himself consequence, he told him that he had a daughter who could spin gold out of straw. The king said to the miller, “That is an art that pleases me well; if thy daughter is as clever as you say, bring her to my castle to-morrow, that I may put her to the proof.”

When the girl was brought to him, he led her into a room that was quite full of straw, and gave her a wheel and spindle, and said, “Now set to work, and if by the early morning thou hast not spun this straw to gold thou shalt die.” And he shut the door himself, and left her there alone. And so the poor miller’s daughter was left there sitting, and could not think what to do for her life: she had no notion how to set to work to spin gold from straw, and her distress grew so great that she began to weep. Then all at once the door opened, and in came a little man, who said, “Good evening, miller’s daughter; why are you crying?”

“Oh!” answered the girl, “I have got to spin gold out of straw, and I don’t understand the business.” Then the little man said, “What will you give me if I spin it for you?” – “My necklace,” said the girl. The little man took the necklace, seated himself before the wheel, and whirr, whirr, whirr! three times round and the bobbin was full; then he took up another, and whirr, whirr, whirr! three times round, and that was full; and so he went on till the morning, when all the straw had been spun, and all the bobbins were full of gold.

“Oh!” answered the girl, “I have got to spin gold out of straw, and I don’t understand the business.” Then the little man said, “What will you give me if I spin it for you?” – “My necklace,” said the girl. The little man took the necklace, seated himself before the wheel, and whirr, whirr, whirr! three times round and the bobbin was full; then he took up another, and whirr, whirr, whirr! three times round, and that was full; and so he went on till the morning, when all the straw had been spun, and all the bobbins were full of gold.

At sunrise came the king, and when he saw the gold he was astonished and very much rejoiced, for he was very avaricious. He had the miller’s daughter taken into another room filled with straw, much bigger than the last, and told her that as she valued her life she must spin it all in one night. The girl did not know what to do, so she began to cry, and then the door opened, and the little man appeared and said, “What will you give me if I spin all this straw into gold?” – “The ring from my finger,” answered the girl. So the little man took the ring, and began again to send the wheel whirring round, and by the next morning all the straw was spun into glistening gold. The king was rejoiced beyond measure at the sight, but as he could never have enough of gold, he had the miller’s daughter taken into a still larger room full of straw, and said, “This, too, must be spun in one night, and if you accomplish it you shall be my wife.” For he thought, “Although she is but a miller’s daughter, I am not likely to find any one richer in the whole world.” As soon as the girl was left alone, the little man appeared for the third time and said, “What will you give me if I spin the straw for you this time?” – “I have nothing left to give,” answered the girl. “Then you must promise me the first child you have after you are queen,” said the little man. “But who knows whether that will happen?” thought the girl; but as she did not know what else to do in her necessity, she promised the little man what he desired, upon which he began to spin, until all the straw was gold. And when in the morning the king came and found all done according to his wish, he caused the wedding to be held at once, and the miller’s pretty daughter became a queen.

In a year’s time she brought a fine child into the world, and thought no more of the little man; but one day he came suddenly into her room, and said, “Now give me what you promised me.” The queen was terrified greatly, and offered the little man all the riches of the kingdom if he would only leave the child; but the little man said, “No, I would rather have something living than all the treasures of the world.” Then the queen began to lament and to weep, so that the little man had pity upon her. “I will give you three days,” said he, “and if at the end of that time you cannot tell my name, you must give up the child to me.”

In a year’s time she brought a fine child into the world, and thought no more of the little man; but one day he came suddenly into her room, and said, “Now give me what you promised me.” The queen was terrified greatly, and offered the little man all the riches of the kingdom if he would only leave the child; but the little man said, “No, I would rather have something living than all the treasures of the world.” Then the queen began to lament and to weep, so that the little man had pity upon her. “I will give you three days,” said he, “and if at the end of that time you cannot tell my name, you must give up the child to me.”

Then the queen spent the whole night in thinking over all the names that she had ever heard, and sent a messenger through the land to ask far and wide for all the names that could be found. And when the little man came next day, (beginning with Caspar, Melchior, Balthazar) she repeated all she knew, and went through the whole list, but after each the little man said, “That is not my name.” The second day the queen sent to inquire of all the neighbours what the servants were called, and told the little man all the most unusual and singular names, saying, “Perhaps you are called Roast-ribs, or Sheepshanks, or Spindleshanks?” But he answered nothing but “That is not my name.” The third day the messenger came back again, and said, “I have not been able to find one single new name; but as I passed through the woods I came to a high hill, and near it was a little house, and before the house burned a fire, and round the fire danced a comical little man, and he hopped on one leg and cried,

“To-day do I bake, to-morrow I brew,

“To-day do I bake, to-morrow I brew,

The day after that the queen’s child comes in;

And oh! I am glad that nobody knew

That the name I am called is Rumpelstiltskin!”

You cannot think how pleased the queen was to hear that name, and soon afterwards, when the little man walked in and said, “Now, Mrs Queen, what is my name?” she said at first, “Are you called Jack?” – “No,” answered he. “Are you called Harry?” she asked again. “No,” answered he. And then she said, “Then perhaps your name is Rumpelstiltskin?”

“The Devil told you that! the Devil told you that!” cried the little man, and in his anger he stamped with his right foot so hard that it went into the ground above his knee; then he seized his left foot with both his hands in such a fury that he split in two, and there was an end of him.

THE END

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859). This Brothers Grimm version of the story has been translated in 1844 into English by Margarate Hunt. KHM1 055: Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

Hans Christian Andersen

(1805—1875)

Pen and inkstand

In a poet’s study, somebody made a remark as he looked at the inkstand that was standing on the table: “It’s strange what can come out of that inkstand! I wonder what the next thing will be. Yes, it’s strange!”

“That it is!” said the Inkstand. “It’s unbelievable, that’s what I have always said.” The Inkstand was speaking to the Pen and to everything else on the table that could hear it. “It’s really amazing what comes out of me! Almost incredible! I actually don’t know myself what will come next when that person starts to dip into me. One drop from me is enough for half a piece of paper, and what may not be on it then? I am something quite remarkable. All the works of this poet come from me. These living characters, whom people think they recognize, these deep emotions, that gay humor, the charming descriptions of nature – I don’t understand those myself, because I don’t know anything about nature – all of that is in me. From me have come out, and still come out, that host of lovely maidens and brave knights on snorting steeds. The fact is, I assure you, I don’t know anything about them myself.”

“You are right about that,” said the Pen. “You have very few ideas, and don’t bother about thinking much at all. If you did take the trouble to think, you would understand that nothing comes out of you except a liquid. You just supply me with the means of putting down on paper what I have in me; that’s what I write with. It’s the pen that does the writing. Nobody doubts that, and most people know as much about poetry as an old inkstand!”

“You haven’t had much experience,” retorted the Inkstand. “You’ve hardly been in service a week, and already you’re half worn out. Do you imagine you’re the poet? Why, you’re only a servant; I have had a great many like you before you came, some from the goose family and some of English make. I’m familiar with both quill pens and steel pens. Yes, I’ve had a great many in my service, and I’ll have many more when the man who goes through the motions for me comes to write down what he gets from me. I’d be much interested in knowing what will be the next thing he gets from me.”

“Inkpot!” cried the Pen.

Late that evening the Poet came home. He had been at a concert, had heard a splendid violinist, and was quite thrilled with his marvelous performance. From his instrument he had drawn a golden river of melody. Sometimes it had sounded like the gentle murmur of rippling water drops, wonderful pearl-like tones, sometimes like a chorus of twittering birds, sometimes like a tempest tearing through mighty forests of pine. The Poet had fancied he heard his own heart weep, but in tones as sweet as the gentle voice of a woman. It seemed as if the music came not only from the strings of the violin, but from its sounding board, its pegs, its very bridge. It was amazing! The selection had been extremely difficult, but it had seemed as if the bow were wandering over the strings merely in play. The performance was so easy that an ignorant listener might have thought he could do it himself. The violin seemed to sound, and the bow to play, of their own accord, and one forgot the master who directed them, giving them life and soul. Yes, the master was forgotten, but the Poet remembered him. He repeated his name and wrote down his thoughts.

“How foolish it would be for the violin and bow to boast of their achievements! And yet we human beings often do so. Poets, artists, scientists, generals – we are all proud of ourselves, and yet we’re only instruments in the hands of our Lord! To Him alone be the glory! We have nothing to be arrogant about.”

Yes, that is what the Poet wrote down, and he titled his essay, “The Master and the Instruments.”

“That ought to hold you, madam,” said the Pen, when the two were alone again. “Did you hear him read aloud what I had written?”

“Yes, I heard what I gave you to write,” said the Inkstand. “It was meant for you and your conceit. It’s strange that you can’t tell when anyone is making fun of you. I gave you a pretty sharp cut there; surely I must know my own satire!”

“Inkpot!” said the Pen.

“Scribble-stick!” said the Inkstand.

They were both satisfied with their answers, and it is a great comfort to feel that one has made a witty reply – one sleeps better afterward. So they both went to sleep.

But the Poet didn’t sleep. His thoughts rushed forth like the violin’s tones, falling like pearls, sweeping on like a storm through the forest. He understood the sentiments of his own heart; he caught a ray of the light from the everlasting Master.

To him alone be the glory!

END

Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales and stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andersen, Andersen, Hans Christian, Archive A-B, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm ♦ The Girl Without Hands or The Armless Maiden ♦ A certain miller had little by little fallen into poverty, and had nothing left but his mill and a large apple-tree behind it. Once when he had gone into the forest to fetch wood, an old man stepped up to him whom he had never seen before, and said, “Why dost thou plague thyself with cutting wood, I will make thee rich, if thou wilt promise me what is standing behind thy mill?” – “What can that be but my apple-tree?” thought the miller, and said, “Yes,” and gave a written promise to the stranger. He, however, laughed mockingly and said, “When three years have passed, I will come and carry away what belongs to me,” and then he went. When the miller got home, his wife came to meet him and said, “Tell me, miller, from whence comes this sudden wealth into our house? All at once every box and chest was filled; no one brought it in, and I know not how it happened.” He answered, “It comes from a stranger who met me in the forest, and promised me great treasure. I, in return, have promised him what stands behind the mill; we can very well give him the big apple-tree for it.” – “Ah, husband,” said the terrified wife, “that must have been the Devil! He did not mean the apple-tree, but our daughter, who was standing behind the mill sweeping the yard.”

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm ♦ The Girl Without Hands or The Armless Maiden ♦ A certain miller had little by little fallen into poverty, and had nothing left but his mill and a large apple-tree behind it. Once when he had gone into the forest to fetch wood, an old man stepped up to him whom he had never seen before, and said, “Why dost thou plague thyself with cutting wood, I will make thee rich, if thou wilt promise me what is standing behind thy mill?” – “What can that be but my apple-tree?” thought the miller, and said, “Yes,” and gave a written promise to the stranger. He, however, laughed mockingly and said, “When three years have passed, I will come and carry away what belongs to me,” and then he went. When the miller got home, his wife came to meet him and said, “Tell me, miller, from whence comes this sudden wealth into our house? All at once every box and chest was filled; no one brought it in, and I know not how it happened.” He answered, “It comes from a stranger who met me in the forest, and promised me great treasure. I, in return, have promised him what stands behind the mill; we can very well give him the big apple-tree for it.” – “Ah, husband,” said the terrified wife, “that must have been the Devil! He did not mean the apple-tree, but our daughter, who was standing behind the mill sweeping the yard.”

The miller’s daughter was a beautiful, pious girl, and lived through the three years in the fear of God and without sin. When therefore the time was over, and the day came when the Evil-one was to fetch her, she washed herself clean, and made a circle round herself with chalk. The devil appeared quite early, but he could not come near to her. Angrily, he said to the miller, “Take all water away from her, that she may no longer be able to wash herself, for otherwise I have no power over her.” The miller was afraid, and did so. The next morning the devil came again, but she had wept on her hands, and they were quite clean. Again he could not get near her, and furiously said to the miller, “Cut her hands off, or else I cannot get the better of her.” The miller was shocked and answered, “How could I cut off my own child’s hands?” Then the Evil-one threatened him and said, “If thou dost not do it thou art mine, and I will take thee thyself.” The father became alarmed, and promised to obey him. So he went to the girl and said, “My child, if I do not cut off both thine hands, the devil will carry me away, and in my terror I have promised to do it. Help me in my need, and forgive me the harm I do thee.” She replied, “Dear father, do with me what you will, I am your child.” Thereupon she laid down both her hands, and let them be cut off. The devil came for the third time, but she had wept so long and so much on the stumps, that after all they were quite clean. Then he had to give in, and had lost all right over her.

The miller said to her, “I have by means of thee received such great wealth that I will keep thee most delicately as long as thou livest.” But she replied, “Here I cannot stay, I will go forth, compassionate people will give me as much as I require.” Thereupon she caused her maimed arms to be bound to her back, and by sunrise she set out on her way, and walked the whole day until night fell. Then she came to a royal garden, and by the shimmering of the moon she saw that trees covered with beautiful fruits grew in it, but she could not enter, for there was much water round about it. And as she had walked the whole day and not eaten one mouthful, and hunger tormented her, she thought, “Ah, if I were but inside, that I might eat of the fruit, else must I die of hunger!” Then she knelt down, called on God the Lord, and prayed. And suddenly an angel came towards her, who made a dam in the water, so that the moat became dry and she could walk through it. And now she went into the garden and the angel went with her. She saw a tree covered with beautiful pears, but they were all counted. Then she went to them, and to still her hunger, ate one with her mouth from the tree, but no more. The gardener was watching; but as the angel was standing by, he was afraid and thought the maiden was a spirit, and was silent, neither did he dare to cry out, or to speak to the spirit. When she had eaten the pear, she was satisfied, and went and concealed herself among the bushes. The King to whom the garden belonged, came down to it next morning, and counted, and saw that one of the pears was missing, and asked the gardener what had become of it, as it was not lying beneath the tree, but was gone. Then answered the gardener, “Last night, a spirit came in, who had no hands, and ate off one of the pears with its mouth.” The King said, “How did the spirit get over the water, and where did it go after it had eaten the pear?” The gardener answered, “Some one came in a snow-white garment from heaven who made a dam, and kept back the water, that the spirit might walk through the moat. And as it must have been an angel, I was afraid, and asked no questions, and did not cry out. When the spirit had eaten the pear, it went back again.” The King said, “If it be as thou sayest, I will watch with thee to-night.”

The miller said to her, “I have by means of thee received such great wealth that I will keep thee most delicately as long as thou livest.” But she replied, “Here I cannot stay, I will go forth, compassionate people will give me as much as I require.” Thereupon she caused her maimed arms to be bound to her back, and by sunrise she set out on her way, and walked the whole day until night fell. Then she came to a royal garden, and by the shimmering of the moon she saw that trees covered with beautiful fruits grew in it, but she could not enter, for there was much water round about it. And as she had walked the whole day and not eaten one mouthful, and hunger tormented her, she thought, “Ah, if I were but inside, that I might eat of the fruit, else must I die of hunger!” Then she knelt down, called on God the Lord, and prayed. And suddenly an angel came towards her, who made a dam in the water, so that the moat became dry and she could walk through it. And now she went into the garden and the angel went with her. She saw a tree covered with beautiful pears, but they were all counted. Then she went to them, and to still her hunger, ate one with her mouth from the tree, but no more. The gardener was watching; but as the angel was standing by, he was afraid and thought the maiden was a spirit, and was silent, neither did he dare to cry out, or to speak to the spirit. When she had eaten the pear, she was satisfied, and went and concealed herself among the bushes. The King to whom the garden belonged, came down to it next morning, and counted, and saw that one of the pears was missing, and asked the gardener what had become of it, as it was not lying beneath the tree, but was gone. Then answered the gardener, “Last night, a spirit came in, who had no hands, and ate off one of the pears with its mouth.” The King said, “How did the spirit get over the water, and where did it go after it had eaten the pear?” The gardener answered, “Some one came in a snow-white garment from heaven who made a dam, and kept back the water, that the spirit might walk through the moat. And as it must have been an angel, I was afraid, and asked no questions, and did not cry out. When the spirit had eaten the pear, it went back again.” The King said, “If it be as thou sayest, I will watch with thee to-night.”

When it grew dark the King came into the garden and brought a priest with him, who was to speak to the spirit. All three seated themselves beneath the tree and watched. At midnight the maiden came creeping out of the thicket, went to the tree, and again ate one pear off it with her mouth, and beside her stood the angel in white garments3. Then the priest went out to them and said, “Comest thou from heaven or from earth? Art thou a spirit, or a human being?” She replied, “I am no spirit, but an unhappy mortal deserted by all but God.” The King said, “If thou art forsaken by all the world, yet will I not forsake thee.” He took her with him into his royal palace, and as she was so beautiful and good, he loved her with all his heart, had silver hands made for her, and took her to wife.

After a year the King had to take the field4, so he commended his young Queen to the care of his mother and said, “If she is brought to bed take care of her, nurse her well, and tell me of it at once in a letter.” Then she gave birth to a fine boy. So the old mother made haste to write and announce the joyful news to him. But the messenger rested by a brook on the way, and as he was fatigued by the great distance, he fell asleep. Then came the Devil, who was always seeking to injure the good Queen, and exchanged the letter for another, in which was written that the Queen had brought a monster into the world. When the King read the letter he was shocked and much troubled, but he wrote in answer that they were to take great care of the Queen and nurse her well until his arrival. The messenger went back with the letter, but rested at the same place and again fell asleep. Then came the Devil once more, and put a different letter in his pocket, in which it was written that they were to put the Queen and her child to death. The old mother was terribly shocked when she received the letter, and could not believe it. She wrote back again to the King, but received no other answer, because each time the Devil substituted a false letter, and in the last letter it was also written that she was to preserve the Queen’s tongue and eyes as a token that she had obeyed.

After a year the King had to take the field4, so he commended his young Queen to the care of his mother and said, “If she is brought to bed take care of her, nurse her well, and tell me of it at once in a letter.” Then she gave birth to a fine boy. So the old mother made haste to write and announce the joyful news to him. But the messenger rested by a brook on the way, and as he was fatigued by the great distance, he fell asleep. Then came the Devil, who was always seeking to injure the good Queen, and exchanged the letter for another, in which was written that the Queen had brought a monster into the world. When the King read the letter he was shocked and much troubled, but he wrote in answer that they were to take great care of the Queen and nurse her well until his arrival. The messenger went back with the letter, but rested at the same place and again fell asleep. Then came the Devil once more, and put a different letter in his pocket, in which it was written that they were to put the Queen and her child to death. The old mother was terribly shocked when she received the letter, and could not believe it. She wrote back again to the King, but received no other answer, because each time the Devil substituted a false letter, and in the last letter it was also written that she was to preserve the Queen’s tongue and eyes as a token that she had obeyed.

But the old mother wept to think such innocent blood was to be shed, and had a hind brought by night and cut out her tongue and eyes, and kept them. Then said she to the Queen, “I cannot have thee killed as the King commands, but here thou mayst stay no longer. Go forth into the wide world with thy child, and never come here again.” The poor woman tied her child on her back, and went away with eyes full of tears. She came into a great wild forest, and then she fell on her knees and prayed to God, and the angel of the Lord appeared to her and led her to a little house on which was a sign with the words, “Here all dwell free.” A snow-white maiden came out of the little house and said, ‘Welcome, Lady Queen,” and conducted her inside. Then they unbound the little boy from her back, and held him to her breast that he might feed, and laid him in a beautifully-made little bed. Then said the poor woman, “From whence knowest thou that I was a queen?” The white maiden answered, “I am an angel sent by God, to watch over thee and thy child.” The Queen stayed seven7 years in the little house, and was well cared for, and by God’s grace, because of her piety, her hands which had been cut off, grew once more.

At last the King came home again from the war, and his first wish was to see his wife and the child. Then his aged mother began to weep and said, “Thou wicked man, why didst thou write to me that I was to take those two innocent lives?” and she showed him the two letters which the Evil-one had forged, and then continued, “I did as thou badest me,” and she showed the tokens, the tongue and eyes. Then the King began to weep for his poor wife and his little son so much more bitterly than she was doing, that the aged mother had compassion on him and said, “Be at peace, she still lives; I secretly caused a hind to be killed, and took these tokens from it; but I bound the child to thy wife’s back and bade her go forth into the wide world, and made her promise never to come back here again, because thou wert so angry with her.” Then spoke the King, “I will go as far as the sky is blue, and will neither eat nor drink until I have found again my dear wife and my child, if in the meantime they have not been killed, or died of hunger.”

Thereupon the King travelled about for seven long years, and sought her in every cleft of the rocks and in every cave, but he found her not, and thought she had died of want. During the whole of this time he neither ate nor drank, but God supported him. At length he came into a great forest, and found therein the little house whose sign was, “Here all dwell free.” Then forth came the white maiden, took him by the hand, led him in, and said, “Welcome, Lord King,” and asked him from whence he came. He answered, “Soon shall I have travelled about for the space of seven years, and I seek my wife and her child, but cannot find them.” The angel offered him meat and drink, but he did not take anything, and only wished to rest a little. Then he lay down to sleep, and put a handkerchief over his face.

Thereupon the King travelled about for seven long years, and sought her in every cleft of the rocks and in every cave, but he found her not, and thought she had died of want. During the whole of this time he neither ate nor drank, but God supported him. At length he came into a great forest, and found therein the little house whose sign was, “Here all dwell free.” Then forth came the white maiden, took him by the hand, led him in, and said, “Welcome, Lord King,” and asked him from whence he came. He answered, “Soon shall I have travelled about for the space of seven years, and I seek my wife and her child, but cannot find them.” The angel offered him meat and drink, but he did not take anything, and only wished to rest a little. Then he lay down to sleep, and put a handkerchief over his face.

Thereupon the angel went into the chamber where the Queen sat with her son, whom she usually called “Sorrowful,” and said to her, “Go out with thy child, thy husband hath come.” So she went to the place where he lay, and the handkerchief fell from his face. Then said she, “Sorrowful, pick up thy father’s handkerchief, and cover his face again.” The child picked it up, and put it over his face again. The King in his sleep heard what passed, and had pleasure in letting the handkerchief fall once more. But the child grew impatient, and said, “Dear mother, how can I cover my father’s face when I have no father in this world? I have learnt to say the prayer, ‘Our Father, which art in Heaven,’ thou hast told me that my father was in Heaven, and was the good God, and how can I know a wild man like this? He is not my father.” When the King heard that, he got up, and asked who they were. Then said she, “I am thy wife, and that is thy son, Sorrowful.” And he saw her living hands, and said, “My wife had silver hands.” She answered, “The good God has caused my natural hands to grow again;” and the angel went into the inner room, and brought the silver hands, and showed them to him. Hereupon he knew for a certainty that it was his dear wife and his dear child, and he kissed them, and was glad, and said, “A heavy stone has fallen from off mine heart.” Then the angel of God gave them one meal with her, and after that they went home to the King’s aged mother. There were great rejoicings everywhere, and the King and Queen were married again, and lived contentedly to their happy end.

THE END

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859). This Brothers Grimm version of the story has been translated in 1844 into English by Margarate Hunt. KHM1 031: Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The story of the youth who went forth to learn what fear was ♦ A certain father had two sons, the elder of whom was smart and sensible, and could do everything, but the younger was stupid and could neither learn nor understand anything, and when people saw him they said, “There’s a fellow who will give his father some trouble!” When anything had to be done, it was always the elder who was forced to do it; but if his father bade him fetch anything when it was late, or in the night-time, and the way led through the churchyard, or any other dismal place, he answered “Oh, no, father, I’ll not go there, it makes me shudder!” for he was afraid. Or when stories were told by the fire at night which made the flesh creep, the listeners sometimes said “Oh, it makes us shudder!” The younger sat in a corner and listened with the rest of them, and could not imagine what they could mean. “They are always saying ‘it makes me shudder, it makes me shudder!’ It does not make me shudder,” thought he. “That, too, must be an art of which I understand nothing.”

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The story of the youth who went forth to learn what fear was ♦ A certain father had two sons, the elder of whom was smart and sensible, and could do everything, but the younger was stupid and could neither learn nor understand anything, and when people saw him they said, “There’s a fellow who will give his father some trouble!” When anything had to be done, it was always the elder who was forced to do it; but if his father bade him fetch anything when it was late, or in the night-time, and the way led through the churchyard, or any other dismal place, he answered “Oh, no, father, I’ll not go there, it makes me shudder!” for he was afraid. Or when stories were told by the fire at night which made the flesh creep, the listeners sometimes said “Oh, it makes us shudder!” The younger sat in a corner and listened with the rest of them, and could not imagine what they could mean. “They are always saying ‘it makes me shudder, it makes me shudder!’ It does not make me shudder,” thought he. “That, too, must be an art of which I understand nothing.”

Now it came to pass that his father said to him one day “Hearken to me, thou fellow in the corner there, thou art growing tall and strong, and thou too must learn something by which thou canst earn thy living. Look how thy brother works, but thou dost not even earn thy salt.” – “Well, father,” he replied, “I am quite willing to learn something – indeed, if it could but be managed, I should like to learn how to shudder. I don’t understand that at all yet.” The elder brother smiled when he heard that, and thought to himself, “Good God, what a blockhead that brother of mine is! He will never be good for anything as long as he lives. He who wants to be a sickle must bend himself betimes.” The father sighed, and answered him “thou shalt soon learn what it is to shudder, but thou wilt not earn thy bread by that.”

Soon after this the sexton2 came to the house on a visit, and the father bewailed his trouble, and told him how his younger son was so backward in every respect that he knew nothing and learnt nothing. “Just think,” said he, “when I asked him how he was going to earn his bread, he actually wanted to learn to shudder.” – “If that be all,” replied the sexton, “he can learn that with me. Send him to me, and I will soon polish him.” The father was glad to do it, for he thought, “It will train the boy a little.” The sexton therefore took him into his house, and he had to ring the bell. After a day or two, the sexton awoke him at midnight, and bade him arise and go up into the church tower and ring the bell. “Thou shalt soon learn what shuddering is,” thought he, and secretly went there before him; and when the boy was at the top of the tower and turned round, and was just going to take hold of the bell rope, he saw a white figure standing on the stairs opposite the sounding hole. “Who is there?” cried he, but the figure made no reply, and did not move or stir. “Give an answer,” cried the boy, “or take thy self off, thou hast no business here at night.” The sexton, however, remained standing motionless that the boy might think he was a ghost. The boy cried a second time, “What do you want here? – speak if thou art an honest fellow, or I will throw thee down the steps!” The sexton thought, “he can’t intend to be as bad as his words,” uttered no sound and stood as if he were made of stone. Then the boy called to him for the third time, and as that was also to no purpose, he ran against him and pushed the ghost down the stairs, so that it fell down ten steps and remained lying there in a corner. Thereupon he rang the bell, went home, and without saying a word went to bed, and fell asleep. The sexton’s wife waited a long time for her husband, but he did not come back. At length she became uneasy, and wakened the boy, and asked, “Dost thou not know where my husband is? He climbed up the tower before thou didst.” – “No, I don’t know,” replied the boy, “but some one was standing by the sounding hole on the other side of the steps, and as he would neither give an answer nor go away, I took him for a scoundrel, and threw him downstairs, just go there and you will see if it was he. I should be sorry if it were.” The woman ran away and found her husband, who was lying moaning in the corner, and had broken his leg.

She carried him down, and then with loud screams she hastened to the boy’s father. “Your boy,” cried she, “has been the cause of a great misfortune! He has thrown my husband down the steps and made him break his leg. Take the good-for-nothing fellow away from our house.” The father was terrified, and ran thither and scolded the boy. “What wicked tricks are these?” said he, “the Devil must have put this into thy head.” – “Father,” he replied, “do listen to me. I am quite innocent. He was standing there by night like one who is intending to do some evil. I did not know who it was, and I entreated him three times either to speak or to go away.” – “Ah,” said the father, “I have nothing but unhappiness with you. Go out of my sight. I will see thee no more.” – “Yes, father, right willingly, wait only until it is day. Then will I go forth and learn how to shudder, and then I shall, at any rate, understand one art which will support me.” – “Learn what thou wilt,” spake the father, “it is all the same to me. Here are fifty thalers3 for thee. Take these and go into the wide world, and tell no one from whence thou comest, and who is thy father, for I have reason to be ashamed of thee.” – “Yes, father, it shall be as you will. If you desire nothing more than that, I can easily keep it in mind.”