Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Nexus-Masterclass door

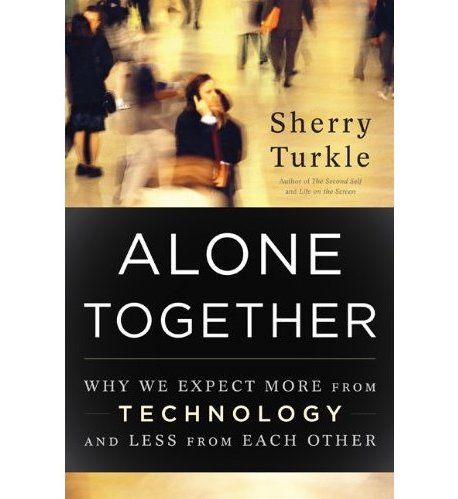

Sherry Turkle

Alone Together

Identity and Digital Culture

Amerikaanse jongeren nemen de telefoon al niet meer op. Communiceren doe je via whatsapp, twitter en Facebook. Elk nieuw bericht trekt onweerstaanbaar de aandacht. Daarom heeft iedereen nu een telefoon in zijn hand: reizigers in de trein, ouders en kinderen op het schoolplein, vrienden in het café, studenten in de collegezaal. Wat zijn de gevolgen van non-stop met elkaar verbonden zijn voor mensen persoonlijk? En voor de samenleving als geheel?

Sherry Turkle pleit voor een digitale ethiek. Hoe moet die eruitzien? Daarover wil zij tijdens de Nexus-masterclass in debat met studenten, volgens onderzoek de meest intensieve gebruikers van sociale media.

Donderdagmiddag 22 september

16:00 – 18:00 uur

Aula Tilburg University

Sherry Turkle (1948) is Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology in the Program in Science, Technology, and Society at MIT and the founder (2001) and current director of the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self. Professor Turkle received a joint doctorate in sociology and personality psychology from Harvard University and is a licensed clinical psychologist.

Professor Turkle is the author of Psychoanalytic Politics: Jacques Lacan and Freud’s French Revolution (Basic Books, 1978; MIT Press paper, 1981; second revised edition, Guilford Press, 1992); The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit (Simon and Schuster, 1984; Touchstone paper, 1985; second revised edition, MIT Press, 2005); Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet (Simon and Schuster, 1995; Touchstone paper, 1997); and Simulation and Its Discontents (MIT Press, 2009). She is the editor of three books about things and thinking, all published by the MIT Press: Evocative Objects: Things We Think With (2007); Falling for Science: Objects in Mind (2008); and The Inner History of Devices (2008).Professor Turkle’s most recent book is Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other, published by Basic Books in January 2011.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Nexus Instituut, The talk of the town

Nexus-conferentie 2011

The Questor Hero

Gustav Mahler’s Ultimate Questions

on Man, Art and God

Zaterdag 14 mei 2011

9.40 — 17.30 uur

Muziektheater Amsterdam

Iván Fischer – Yoel Gamzou – Claudio Magris

Katie Mitchell – Antonio Damasio – Lewis Wolpert

Michael P. Steinberg – Nuria Schoenberg Nono

Slavoj Žižek – Carl Niekerk – Allan Janik

Constantin Floros – Adam Zagajewski

In samenwerking met het Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest

Programma Nexus-conferentie

Zaterdag 14 mei 2011

Muziektheater Amsterdam

9.40 u. Welkom Rob Riemen

9.45 u. Keynote lezing Iván Fischer

10.45 u. Pauze

11.15 u. i. commedia humana

Inleiding Claudio Magris

Discussie met Iván Fischer, Katie Mitchell, Carl Niekerk,

Nuria Schoenberg Nono en Michael P. Steinberg o.l.v. Rob Riemen

13.00 u. Lunch

14.00 u. ii. creator spiritus

Masterclass On Mahler’s Musical Questions door Yoel Gamzou,

m.m.v. leden van het Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest

15.30 u. Pauze

16.00 u. iii. faust or percival?

Discussie met Antonio Damasio, Constantin Floros, Allan Janik,

Lewis Wolpert, Adam Zagajewski en Slavoj Žižek o.l.v. Rob Riemen

17.30 u. Receptie

Op vrijdag 13 mei, aan de vooravond van de Nexus-conferentie, en op zon-

dag 15 mei vindt in de Grote Zaal van het Concertgebouw in Amsterdam

een uitvoering plaats van de Negende Symfonie van Gustav Mahler door het

Koninklijk Concertgebouworkest onder leiding van dirigent Bernard Haitink.

Zie www.concertgebouworkest.nl

Sprekers

antonio damasio (Portugal, 1944) verricht baanbrekend onderzoek naar

de manier waarop het brein herinneringen, taal, emoties en beslissingen

verwerkt. Hij dankt zijn wereldfaam ook aan internationale bestsellers als

Descartes’ Error. Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain (1994) en Looking for

Spinoza. Joy, Sorrow, and the Feeling Brain (2003). In zijn meest recente boek,

Self Comes to Mind. Constructing the Conscious Brain (2010), stelt hij dat het brein

en het bewustzijn, net als het lichaam, deel uitmaken van een biologisch-

evolutionair proces. Damasio is David Dornsife Professor of Neuroscience en

directeur van het Brain and Creativity Institute aan de University of Southern

California. In Nexus 51 publiceerde hij een essay over modern Arcadië.

iván fischer (Hongarije, 1951) wordt alom geprezen om zijn grote

verdiensten als dirigent van het Boedapest Festival Orkest, dat door hem

in 1983 werd opgericht en waarvan hij nog steeds chef-dirigent is. Hij nam

het initiatief tot de oprichting van de Hongaarse Mahler Vereniging en het

Boedapester Mahlerfeest. Na zijn studie piano, viool, cello en compositieleer

in Boedapest en Wenen heeft Fischer zich toegelegd op orkestdirectie

onder auspiciën van onder anderen Hans Swarowsky. Al op jonge leeftijd

assisteerde hij Nikolaus Harnoncourt bij het Mozarteum in Salzburg. Na

zijn internationale doorbraak op 25-jarige leeftijd heeft hij als dirigent voor

’s werelds meest gerenommeerde orkesten gestaan. Momenteel is hij gastdirigent

van het Concertgebouworkest en hoofddirigent van het Nationaal

Symfonieorkest van Washington dc. Hij wordt veelvuldig gevraagd voor

de Berliner Philharmoniker, de New York Philharmonic en het Cleveland

Orchestra. Fischer is lid van de Raad van Advies van het Nexus Instituut.

constantin floros (Griekenland, 1930) behoort tot de selecte groep

van topexperts op het gebied van Gustav Mahler. Met zijn driedelige studie

over Mahler (1977-1985) vestigde hij zijn naam als een van de founding

fathers van de moderne Mahlerforschung. Floros, nu emeritus hoogleraar aan

de Universiteit van Hamburg, studeerde musicologie, kunstgeschiedenis,

filosofie en psychologie aan de Universiteit van Wenen en compositie en

directie aan de Weense Muziekacademie. Aan de Universiteit van Hamburg

deed hij onderzoek naar Byzantijnse en Slavische muziek en publiceerde hij

standaardwerken over Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner, Tsjaikovsky, Berg en

Ligeti. Hij entameerde de oprichting van de Gustav Mahler Vereinigung,

waarvan hij nu erevoorzitter is. Voor zijn verdiensten honoreerde het

Internationale Gustav Mahler Gesellschaft hem vorig jaar met de Gouden

Mahler-medaille. In Nexus 1 schreef hij over de actualiteit van Gustav Mahler.

yoel gamzou (Israël, 1985) is een jonge, verbijsterende komeet aan het

Mahler-firmament. Hij richtte in 2006 het International Mahler Orchestra

op en werd daar directeur en chef-dirigent van. Als wonderkind imponeerde

hij door zijn cellospel en dirigeertalent. Hij studeerde in Tel Aviv, New York,

Parijs en Milaan en was de laatste grote leerling van Carlo Maria Giulini.

Sinds 2010 mag hij zich chef-dirigent noemen van de Neue Philharmonie in

München. Gamzou heeft zich vooral toegelegd op de werken van Mahler.

Met steun van het Internationale Gustav Mahler Gesellschaft en enkele

wetenschappers heeft hij sinds 2004 gewerkt aan de ‘voltooiing’ van Mahlers

onvoltooid gebleven Tiende Symfonie, die op 5 september 2010 haar geruchtmakende

première beleefde in Berlijn.

allan janik (Verenigde Staten, 1941) promoveerde in 1971 in de filosofie

aan Brandeis University. Tot aan zijn pensionering was hij verbonden aan het

Forschungsinstitut Brenner-Archiv van de universiteit van Innsbruck, naast zijn

hoogleraarschappen cultuurgeschiedenis en filosofie aan de universiteiten van

Wenen en Innsbruck en het Royal Institute of Technology te Stockholm. Hij

schreef Wittgenstein’s Vienna (1973, samen met Stephen Toulmin, Ned. vert. Het

Wenen van Wittgenstein), Essays on Wittgenstein and Weininger (1985), Wittgenstein

in Vienna. A Biographical Excursion Through the City and its History (1998), The

Use and Abuse of Metaphor (2003) en Empty Sleeve: Paul Wittgenstein (2006). Janik

publiceerde eerder in Nexus 9, 12, 15, 21, 37, 50 en 53.

claudio magris (Italië, 1939) vormt samen met Umberto Eco en Roberto

Calasso De Grote Drie van de moderne Italiaanse literatuur. Zijn imposante

oeuvre telt essays, romans, theaterstukken, vertalingen en cultuurfilosofische

beschouwingen. Ruime bekendheid verwierf hij met Danubio (Donau,

1986), zijn brede panorama van de geschiedenis van Midden-Europa. Veel

van zijn boeken, waaronder Un altro mare (1991) en Microcosmi (1997), zijn in

vrijwel alle Europese talen vertaald. Magris is sinds 1978 hoogleraar Duitse

letterkunde aan de Universiteit van Triëst en geniet ook faam als columnist

en essayist voor de Corriere della Sera. Halverwege de jaren negentig was hij

enige jaren lid van de Italiaanse Senaat. Hij ontving voor zijn letterkundig en

wetenschappelijk werk vele hoge onderscheidingen, waaronder in 2001 de

Erasmusprijs. In 1997 hield Magris de Nexus-lezing, die gepubliceerd werd

in Nexus 19.

katie mitchell (Groot-Brittannië, 1964) begon haar glanzende carrière als

regisseur bij theatergezelschappen als Paines Plough en de Royal Shakespeare

Company. Haar operadebuut maakte ze in 1996 met Don Giovanni bij de

Welsh National Opera, waarmee zij definitief haar naam vestigde. Haar

veelzijdigheid bewees ze met haar regie van de verfilming van Benjamin

Brittens The Turn of the Screw voor de bbc. In 2009 was zij verantwoordelijk

voor de succesvolle productie van Luigi Nono’s politieke opera Al gran sole

carico d’amore op het Salzburg Festival en in datzelfde jaar bracht ze ook een

nieuwe productie van James MacMillans opera Parthenogenesis op de planken.

Aan het eind van dit jaar regisseert Mitchell bij De Nederlandse Opera de

wereldpremière van Manfred Trojahns opera Orest.

carl niekerk (Nederland, 1964) is universitair hoofddocent germanistiek

aan de Universiteit van Illinois, met als voornaamste onderzoeksgebieden

muziek (Gustav Mahler) en Duits-joodse literatuur. Na zijn studie Duits in

Groningen cum laude te hebben afgerond, verdedigde hij zijn proefschrift

aan Washington University in St. Louis en doceerde daarna aan diverse

Amerikaanse universiteiten. In 2005 publiceerde hij Zwischen Naturgeschichte

und Anthropologie. Lichtenberg im Kontext der Spätaufklärung. Zijn meest recente

boek is Reading Mahler. German Culture and Jewish Identity in Fin-de-Siècle

Vienna (2010), waarin hij de literaire, filosofische en culturele invloeden op

Mahlers denken en musiceren onderzoekt.

nuria schoenberg nono (Spanje, 1932) vervult een unieke rol in

de geschiedenis van de twintigste-eeuwse muziek. Zij is de dochter van

de Weense componist Arnold Schönberg en de weduwe van de Italiaanse

avantgardecomponist Luigi Nono, die zij in 1954 in Hamburg ontmoette bij

de première van Schönbergs onvoltooide opera Moses und Aron. Zij groeide

op in Califonië, waar haar ouders in 1933 uit Berlijn naartoe gevlucht waren,

en vestigde zich in 1955 met haar man in Venetië. In die stad staat zij nu aan

het hoofd van het Luigi Nono Archief, waar de manuscripten, composities,

studies, opnames en persoonlijke documenten van de in 1990 overleden

componist worden bewaard. Zij droeg er tevens zorg voor dat de omvangrijke

nalatenschap van haar vader, door haar jarenlang zorgvuldig geordend,

van Los Angeles verhuisd is naar het Arnold Schönberg Center in Wenen,

waarvan zij sinds de opening in 1998 bestuursvoorzitter is.

michael p. steinberg (Verenigde Staten, 1956) is hoogleraar geschiedenis

en hoogleraar muziekwetenschap aan Brown University. Hij is gespecialiseerd

in Duitse cultuurgeschiedenis, met bijzondere aandacht voor de joodse en

muzikale facetten. Hij was gastdocent aan universiteiten in de Verenigde

Staten, Frankrijk en Taiwan. Steinberg is directeur van het Cogut Center for

the Humanities, redacteur van The Musical Quarterly en The Opera Quarterly

en bestuurslid van de Barenboim-Said Foundation. Hij schreef het spraakmakende

Austria as Theater and Ideology. The Meaning of the Salzburg Festival (2000),

Listening to Reason. Culture, Subjectivity and Nineteenth-century Music (2006) en

Judaism Musical and Unmusical (2007). Momenteel is Steinberg ook betrokken als

adviseur bij de productie van Wagners Ring des Nibelungen in Milaan en Berlijn.

lewis wolpert (Zuid-Afrika, 1929) is emeritus hoogleraar medische

biologie aan de subfaculteit cel- en ontwikkelingsbiologie van het Londense

University College en hoofdredacteur van het Journal of Theoretical Biology. Hij

geniet grote vermaardheid om zijn uitgesproken rationalistische visie op mens

en wetenschap, zoals uiteengezet in onder meer Passionate Minds (1988),The

Unnatural Nature of Science (1994) en Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast. The

Evolutionary Origins of Belief (2006). Met zijn deels autobiografische Malignant

Sadness. The Anatomy of Depression (1999) bereikte hij een groot publiek,

dat nog aangroeide door zijn optredens voor radio en televisie. Wolpert is

voorzitter van het Committee on the Public Understanding of Science en

vice-voorzitter van de Britse Humanistenvereniging.

adam zagajewski (Polen, 1945) schrijft als dichter ook korte verhalen

en essays. Zijn werk kenmerkt zich door een lucide en tragisch bewustzijn

van de existentiële spanning tussen individu en politiek, tussen kunst en

modern vermaak. Hij groeide op in Polen, waar hij psychologie en filosofie

studeerde, en emigreerde in 1982 naar Parijs. Twintig jaar later keerde hij

terug naar Krakau. Zagajewski geldt als een van de grootste dichters van

onze tijd en als Nobelprijskandidaat. In Nederlandse vertaling verschenen

Wat zingt, is wat zwijgt (1998, Nexus Bibliotheek) en Mystiek voor beginners

(2003). Zagajewski is momenteel werkzaam aan de University of Chicago,

waar hij ook zitting heeft in het prestigieuze Committee on Social Thought.

slavoj žižek (Slovenië, 1949) is erin geslaagd zijn naam als polemisch

marxistisch socioloog, filosoof en cultuurcriticus te vestigen in alle uithoeken

van de wereld. Hij promoveerde aan de Universiteit van Ljubljana in de

filosofie en studeerde psychoanalyse aan Universiteit Vincennes-Saint Denis

in Parijs. Žižek maakte school met een nieuwe duiding van populaire cultuur,

waarbij hij het werk van de twintigste-eeuwse Franse psychoanalyticus

Jacques Lacan op vernieuwende wijze inzette. Momenteel is hij hoogleraar

aan de European Graduate School, sociologisch onderzoeker in Ljubljana en

internationaal directeur van het Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities aan

de Universiteit van Londen. Žižek publiceerde in Nexus 54

Aanmelden

Voor het bijwonen van de Nexus-conferentie dient u vooraf een entreebewijs

te bestellen. U kunt dat doen met de Aanmeldkaart in het midden van deze

brochure of via www.nexus-instituut.nl. Bij de entreeprijs zijn de kosten van

consumpties tijdens de pauzes, de lunch en de receptie inbegrepen.

Normaal tarief € 85,00

Abonneetarief € 50,00

U heeft al of neemt nu een abonnement op het tijdschrift Nexus.

U kunt max. drie introducé(e)s meebrengen voor € 50,00 p.p.

Jongerentarief € 25,00

T/m 26 jaar. Stuur of mail een kopie identiteitsbewijs.

Speciaal tarief gratis

Als Vriend van het Nexus Instituut kunt u 2-4 vrijkaarten bestellen.

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Nexus Instituut, The talk of the town

Civil Disobedience

by Henry David Thoreau

I heartily accept the motto, “That government is best which governs least”; and I should like to see it acted up to more rapidly and systematically. Carried out, it finally amounts to this, which also I believe— “That government is best which governs not at all”; and when men are prepared for it, that will be the kind of government which they will have. Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient. The objections which have been brought against a standing army, and they are many and weighty, and deserve to prevail, may also at last be brought against a standing government. The standing army is only an arm of the standing government. The government itself, which is only the mode which the people have chosen to execute their will, is equally liable to be abused and perverted before the people can act through it. Witness the present Mexican war, the work of comparatively a few individuals using the standing government as their tool; for, in the outset, the people would not have consented to this measure.

This American government— what is it but a tradition, though a recent one, endeavoring to transmit itself unimpaired to posterity, but each instant losing some of its integrity? It has not the vitality and force of a single living man; for a single man can bend it to his will. It is a sort of wooden gun to the people themselves. But it is not the less necessary for this; for the people must have some complicated machinery or other, and hear its din, to satisfy that idea of government which they have. Governments show thus how successfully men can be imposed on, even impose on themselves, for their own advantage. It is excellent, we must all allow. Yet this government never of itself furthered any enterprise, but by the alacrity with which it got out of its way. It does not keep the country free. It does not settle the West. It does not educate. The character inherent in the American people has done all that has been accomplished; and it would have done somewhat more, if the government had not sometimes got in its way. For government is an expedient by which men would fain succeed in letting one another alone; and, as has been said, when it is most expedient, the governed are most let alone by it. Trade and commerce, if they were not made of india-rubber, would never manage to bounce over the obstacles which legislators are continually putting in their way; and, if one were to judge these men wholly by the effects of their actions and not partly by their intentions, they would deserve to be classed and punished with those mischievous persons who put obstructions on the railroads.

But, to speak practically and as a citizen, unlike those who call themselves no-government men, I ask for, not at once no government, but at once a better government. Let every man make known what kind of government would command his respect, and that will be one step toward obtaining it.

After all, the practical reason why, when the power is once in the hands of the people, a majority are permitted, and for a long period continue, to rule is not because they are most likely to be in the right, nor because this seems fairest to the minority, but because they are physically the strongest. But a government in which the majority rule in all cases cannot be based on justice, even as far as men understand it. Can there not be a government in which majorities do not virtually decide right and wrong, but conscience?— in which majorities decide only those questions to which the rule of expediency is applicable? Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislation? Why has every man a conscience, then? I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward. It is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right. The only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right. It is truly enough said that a corporation has no conscience; but a corporation of conscientious men is a corporation with a conscience. Law never made men a whit more just; and, by means of their respect for it, even the well-disposed are daily made the agents of injustice. A common and natural result of an undue respect for law is, that you may see a file of soldiers, colonel, captain, corporal, privates, powder-monkeys, and all, marching in admirable order over hill and dale to the wars, against their wills, ay, against their common sense and consciences, which makes it very steep marching indeed, and produces a palpitation of the heart. They have no doubt that it is a damnable business in which they are concerned; they are all peaceably inclined. Now, what are they? Men at all? or small movable forts and magazines, at the service of some unscrupulous man in power? Visit the Navy-Yard, and behold a marine, such a man as an American government can make, or such as it can make a man with its black arts— a mere shadow and reminiscence of humanity, a man laid out alive and standing, and already, as one may say, buried under arms with funeral accompaniments, though it may be,

“Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note,

As his corpse to the rampart we hurried;

Not a soldier discharged his farewell shot

O’er the grave where our hero we buried.”

[Charles Wolfe The Burial of Sir John Moore at Corunna ]

The mass of men serve the state thus, not as men mainly, but as machines, with their bodies. They are the standing army, and the militia, jailers, constables, posse comitatus, etc. In most cases there is no free exercise whatever of the judgment or of the moral sense; but they put themselves on a level with wood and earth and stones; and wooden men can perhaps be manufactured that will serve the purpose as well. Such command no more respect than men of straw or a lump of dirt. They have the same sort of worth only as horses and dogs. Yet such as these even are commonly esteemed good citizens. Others— as most legislators, politicians, lawyers, ministers, and office-holders— serve the state chiefly with their heads; and, as they rarely make any moral distinctions, they are as likely to serve the devil, without intending it, as God. A very few— as heroes, patriots, martyrs, reformers in the great sense, and men— serve the state with their consciences also, and so necessarily resist it for the most part; and they are commonly treated as enemies by it. A wise man will only be useful as a man, and will not submit to be “clay,” and “stop a hole to keep the wind away,” but leave that office to his dust at least:

“I am too high-born to be propertied,

To be a secondary at control,

Or useful serving-man and instrument

To any sovereign state throughout the world.”

[William Shakespeare King John]

He who gives himself entirely to his fellow-men appears to them useless and selfish; but he who gives himself partially to them is pronounced a benefactor and philanthropist.

How does it become a man to behave toward this American government today? I answer, that he cannot without disgrace be associated with it. I cannot for an instant recognize that political organization as my government which is the slave’s government also.

All men recognize the right of revolution; that is, the right to refuse allegiance to, and to resist, the government, when its tyranny or its inefficiency are great and unendurable. But almost all say that such is not the case now. But such was the case, they think, in the Revolution Of ’75. If one were to tell me that this was a bad government because it taxed certain foreign commodities brought to its ports, it is most probable that I should not make an ado about it, for I can do without them. All machines have their friction; and possibly this does enough good to counterbalance the evil. At any rate, it is a great evil to make a stir about it. But when the friction comes to have its machine, and oppression and robbery are organized, I say, let us not have such a machine any longer. In other words, when a sixth of the population of a nation which has undertaken to be the refuge of liberty are slaves, and a whole country is unjustly overrun and conquered by a foreign army, and subjected to military law, I think that it is not too soon for honest men to rebel and revolutionize. What makes this duty the more urgent is the fact that the country so overrun is not our own, but ours is the invading army.

Paley, a common authority with many on moral questions, in his chapter on the “Duty of Submission to Civil Government,” resolves all civil obligation into expediency; and he proceeds to say that “so long as the interest of the whole society requires it, that is, so long as the established government cannot be resisted or changed without public inconveniency, it is the will of God… that the established government be obeyed— and no longer. This principle being admitted, the justice of every particular case of resistance is reduced to a computation of the quantity of the danger and grievance on the one side, and of the probability and expense of redressing it on the other.” Of this, he says, every man shall judge for himself. But Paley appears never to have contemplated those cases to which the rule of expediency does not apply, in which a people, as well as an individual, must do justice, cost what it may. If I have unjustly wrested a plank from a drowning man, I must restore it to him though I drown myself. This, according to Paley, would be inconvenient. But he that would save his life, in such a case, shall lose it. This people must cease to hold slaves, and to make war on Mexico, though it cost them their existence as a people.

In their practice, nations agree with Paley; but does any one think that Massachusetts does exactly what is right at the present crisis?

“A drab of state, a cloth-o’-silver slut,

To have her train borne up, and her soul trail in the dirt.”

[Cyril Tourneur The Revengers Tragadie ]

Practically speaking, the opponents to a reform in Massachusetts are not a hundred thousand politicians at the South, but a hundred thousand merchants and farmers here, who are more interested in commerce and agriculture than they are in humanity, and are not prepared to do justice to the slave and to Mexico, cost what it may. I quarrel not with far-off foes, but with those who, near at home, cooperate with, and do the bidding of those far away, and without whom the latter would be harmless. We are accustomed to say, that the mass of men are unprepared; but improvement is slow, because the few are not materially wiser or better than the many. It is not so important that many should be as good as you, as that there be some absolute goodness somewhere; for that will leaven the whole lump. There are thousands who are in opinion opposed to slavery and to the war, who yet in effect do nothing to put an end to them; who, esteeming themselves children of Washington and Franklin, sit down with their hands in their pockets, and say that they know not what to do, and do nothing; who even postpone the question of freedom to the question of free trade, and quietly read the prices-current along with the latest advices from Mexico, after dinner, and, it may be, fall asleep over them both. What is the price-current of an honest man and patriot today? They hesitate, and they regret, and sometimes they petition; but they do nothing in earnest and with effect. They will wait, well disposed, for others to remedy the evil, that they may no longer have it to regret. At most, they give only a cheap vote, and a feeble countenance and God-speed, to the right, as it goes by them. There are nine hundred and ninety-nine patrons of virtue to one virtuous man. But it is easier to deal with the real possessor of a thing than with the temporary guardian of it.

All voting is a sort of gaming, like checkers or backgammon, with a slight moral tinge to it, a playing with right and wrong, with moral questions; and betting naturally accompanies it. The character of the voters is not staked. I cast my vote, perchance, as I think right; but I am not vitally concerned that that right should prevail. I am willing to leave it to the majority. Its obligation, therefore, never exceeds that of expediency. Even voting for the right is doing nothing for it. It is only expressing to men feebly your desire that it should prevail. A wise man will not leave the right to the mercy of chance, nor wish it to prevail through the power of the majority. There is but little virtue in the action of masses of men. When the majority shall at length vote for the abolition of slavery, it will be because they are indifferent to slavery, or because there is but little slavery left to be abolished by their vote. They will then be the only slaves. Only his vote can hasten the abolition of slavery who asserts his own freedom by his vote.

I hear of a convention to be held at Baltimore, or elsewhere, for the selection of a candidate for the Presidency, made up chiefly of editors, and men who are politicians by profession; but I think, what is it to any independent, intelligent, and respectable man what decision they may come to? Shall we not have the advantage of his wisdom and honesty, nevertheless? Can we not count upon some independent votes? Are there not many individuals in the country who do not attend conventions? But no: I find that the respectable man, so called, has immediately drifted from his position, and despairs of his country, when his country has more reason to despair of him. He forthwith adopts one of the candidates thus selected as the only available one, thus proving that he is himself available for any purposes of the demagogue. His vote is of no more worth than that of any unprincipled foreigner or hireling native, who may have been bought. O for a man who is a man, and, as my neighbor says, has a bone in his back which you cannot pass your hand through! Our statistics are at fault: the population has been returned too large. How many men are there to a square thousand miles in this country? Hardly one. Does not America offer any inducement for men to settle here? The American has dwindled into an Odd Fellow— one who may be known by the development of his organ of gregariousness, and a manifest lack of intellect and cheerful self-reliance; whose first and chief concern, on coming into the world, is to see that the almshouses are in good repair; and, before yet he has lawfully donned the virile garb, to collect a fund for the support of the widows and orphans that may be; who, in short, ventures to live only by the aid of the Mutual Insurance company, which has promised to bury him decently.

It is not a man’s duty, as a matter of course, to devote himself to the eradication of any, even the most enormous, wrong; he may still properly have other concerns to engage him; but it is his duty, at least, to wash his hands of it, and, if he gives it no thought longer, not to give it practically his support. If I devote myself to other pursuits and contemplations, I must first see, at least, that I do not pursue them sitting upon another man’s shoulders. I must get off him first, that he may pursue his contemplations too. See what gross inconsistency is tolerated. I have heard some of my townsmen say, “I should like to have them order me out to help put down an insurrection of the slaves, or to march to Mexico;— see if I would go”; and yet these very men have each, directly by their allegiance, and so indirectly, at least, by their money, furnished a substitute. The soldier is applauded who refuses to serve in an unjust war by those who do not refuse to sustain the unjust government which makes the war; is applauded by those whose own act and authority he disregards and sets at naught; as if the state were penitent to that degree that it differed one to scourge it while it sinned, but not to that degree that it left off sinning for a moment. Thus, under the name of Order and Civil Government, we are all made at last to pay homage to and support our own meanness. After the first blush of sin comes its indifference; and from immoral it becomes, as it were, unmoral, and not quite unnecessary to that life which we have made.

The broadest and most prevalent error requires the most disinterested virtue to sustain it. The slight reproach to which the virtue of patriotism is commonly liable, the noble are most likely to incur. Those who, while they disapprove of the character and measures of a government, yield to it their allegiance and support are undoubtedly its most conscientious supporters, and so frequently the most serious obstacles to reform. Some are petitioning the State to dissolve the Union, to disregard the requisitions of the President. Why do they not dissolve it themselves— the union between themselves and the State— and refuse to pay their quota into its treasury? Do not they stand in the same relation to the State that the State does to the Union? And have not the same reasons prevented the State from resisting the Union which have prevented them from resisting the State?

How can a man be satisfied to entertain an opinion merely, and enjoy it? Is there any enjoyment in it, if his opinion is that he is aggrieved? If you are cheated out of a single dollar by your neighbor, you do not rest satisfied with knowing that you are cheated, or with saying that you are cheated, or even with petitioning him to pay you your due; but you take effectual steps at once to obtain the full amount, and see that you are never cheated again. Action from principle, the perception and the performance of right, changes things and relations; it is essentially revolutionary, and does not consist wholly with anything which was. It not only divides States and churches, it divides families; ay, it divides the individual, separating the diabolical in him from the divine.

Unjust laws exist: shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once? Men generally, under such a government as this, think that they ought to wait until they have persuaded the majority to alter them. They think that, if they should resist, the remedy would be worse than the evil. But it is the fault of the government itself that the remedy is worse than the evil. It makes it worse. Why is it not more apt to anticipate and provide for reform? Why does it not cherish its wise minority? Why does it cry and resist before it is hurt? Why does it not encourage its citizens to be on the alert to point out its faults, and do better than it would have them? Why does it always crucify Christ, and excommunicate Copernicus and Luther, and pronounce Washington and Franklin rebels?

One would think, that a deliberate and practical denial of its authority was the only offence never contemplated by government; else, why has it not assigned its definite, its suitable and proportionate, penalty? If a man who has no property refuses but once to earn nine shillings for the State, he is put in prison for a period unlimited by any law that I know, and determined only by the discretion of those who placed him there; but if he should steal ninety times nine shillings from the State, he is soon permitted to go at large again.

If the injustice is part of the necessary friction of the machine of government, let it go, let it go: perchance it will wear smooth— certainly the machine will wear out. If the injustice has a spring, or a pulley, or a rope, or a crank, exclusively for itself, then perhaps you may consider whether the remedy will not be worse than the evil; but if it is of such a nature that it requires you to be the agent of injustice to another, then, I say, break the law. Let your life be a counter-friction to stop the machine. What I have to do is to see, at any rate, that I do not lend myself to the wrong which I condemn.

As for adopting the ways which the State has provided for remedying the evil, I know not of such ways. They take too much time, and a man’s life will be gone. I have other affairs to attend to. I came into this world, not chiefly to make this a good place to live in, but to live in it, be it good or bad. A man has not everything to do, but something; and because he cannot do everything, it is not necessary that he should do something wrong. It is not my business to be petitioning the Governor or the Legislature any more than it is theirs to petition me; and if they should not bear my petition, what should I do then? But in this case the State has provided no way: its very Constitution is the evil. This may seem to be harsh and stubborn and unconciliatory; but it is to treat with the utmost kindness and consideration the only spirit that can appreciate or deserves it. So is all change for the better, like birth and death, which convulse the body.

I do not hesitate to say, that those who call themselves Abolitionists should at once effectually withdraw their support, both in person and property, from the government of Massachusetts, and not wait till they constitute a majority of one, before they suffer the right to prevail through them. I think that it is enough if they have God on their side, without waiting for that other one. Moreover, any man more right than his neighbors constitutes a majority of one already.

I meet this American government, or its representative, the State government, directly, and face to face, once a year— no more— in the person of its tax-gatherer; this is the only mode in which a man situated as I am necessarily meets it; and it then says distinctly, Recognize me; and the simplest, the most effectual, and, in the present posture of affairs, the indispensablest mode of treating with it on this head, of expressing your little satisfaction with and love for it, is to deny it then. My civil neighbor, the tax-gatherer, is the very man I have to deal with— for it is, after all, with men and not with parchment that I quarrel— and he has voluntarily chosen to be an agent of the government. How shall he ever know well what he is and does as an officer of the government, or as a man, until he is obliged to consider whether he shall treat me, his neighbor, for whom he has respect, as a neighbor and well-disposed man, or as a maniac and disturber of the peace, and see if he can get over this obstruction to his neighborliness without a ruder and more impetuous thought or speech corresponding with his action. I know this well, that if one thousand, if one hundred, if ten men whom I could name— if ten honest men only— ay, if one HONEST man, in this State of Massachusetts, ceasing to hold slaves, were actually to withdraw from this copartnership, and be locked up in the county jail therefor, it would be the abolition of slavery in America. For it matters not how small the beginning may seem to be: what is once well done is done forever. But we love better to talk about it: that we say is our mission. Reform keeps many scores of newspapers in its service, but not one man. If my esteemed neighbor, the State’s ambassador, who will devote his days to the settlement of the question of human rights in the Council Chamber, instead of being threatened with the prisons of Carolina, were to sit down the prisoner of Massachusetts, that State which is so anxious to foist the sin of slavery upon her sister— though at present she can discover only an act of inhospitality to be the ground of a quarrel with her— the Legislature would not wholly waive the subject the following winter.

Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison. The proper place today, the only place which Massachusetts has provided for her freer and less desponding spirits, is in her prisons, to be put out and locked out of the State by her own act, as they have already put themselves out by their principles. It is there that the fugitive slave, and the Mexican prisoner on parole, and the Indian come to plead the wrongs of his race should find them; on that separate, but more free and honorable, ground, where the State places those who are not with her, but against her— the only house in a slave State in which a free man can abide with honor. If any think that their influence would be lost there, and their voices no longer afflict the ear of the State, that they would not be as an enemy within its walls, they do not know by how much truth is stronger than error, nor how much more eloquently and effectively he can combat injustice who has experienced a little in his own person. Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence. A minority is powerless while it conforms to the majority; it is not even a minority then; but it is irresistible when it clogs by its whole weight. If the alternative is to keep all just men in prison, or give up war and slavery, the State will not hesitate which to choose. If a thousand men were not to pay their tax-bills this year, that would not be a violent and bloody measure, as it would be to pay them, and enable the State to commit violence and shed innocent blood. This is, in fact, the definition of a peaceable revolution, if any such is possible. If the tax-gatherer, or any other public officer, asks me, as one has done, “But what shall I do?” my answer is, “If you really wish to do anything, resign your office.” When the subject has refused allegiance, and the officer has resigned his office, then the revolution is accomplished. But even suppose blood should flow. Is there not a sort of blood shed when the conscience is wounded? Through this wound a man’s real manhood and immortality flow out, and he bleeds to an everlasting death. I see this blood flowing now.

I have contemplated the imprisonment of the offender, rather than the seizure of his goods— though both will serve the same purpose— because they who assert the purest right, and consequently are most dangerous to a corrupt State, commonly have not spent much time in accumulating property. To such the State renders comparatively small service, and a slight tax is wont to appear exorbitant, particularly if they are obliged to earn it by special labor with their hands. If there were one who lived wholly without the use of money, the State itself would hesitate to demand it of him. But the rich man— not to make any invidious comparison— is always sold to the institution which makes him rich. Absolutely speaking, the more money, the less virtue; for money comes between a man and his objects, and obtains them for him; and it was certainly no great virtue to obtain it. It puts to rest many questions which he would otherwise be taxed to answer; while the only new question which it puts is the hard but superfluous one, how to spend it. Thus his moral ground is taken from under his feet. The opportunities of living are diminished in proportion as what are called the “means” are increased. The best thing a man can do for his culture when he is rich is to endeavor to carry out those schemes which he entertained when he was poor. Christ answered the Herodians according to their condition. “Show me the tribute-money,” said he;— and one took a penny out of his pocket;— if you use money which has the image of Caesar on it, and which he has made current and valuable, that is, if you are men of the State, and gladly enjoy the advantages of Caesar’s government, then pay him back some of his own when he demands it. “Render therefore to Caesar that which is Caesar’s, and to God those things which are God’s”— leaving them no wiser than before as to which was which; for they did not wish to know.

When I converse with the freest of my neighbors, I perceive that, whatever they may say about the magnitude and seriousness of the question, and their regard for the public tranquillity, the long and the short of the matter is, that they cannot spare the protection of the existing government, and they dread the consequences to their property and families of disobedience to it. For my own part, I should not like to think that I ever rely on the protection of the State. But, if I deny the authority of the State when it presents its tax-bill, it will soon take and waste all my property, and so harass me and my children without end. This is hard. This makes it impossible for a man to live honestly, and at the same time comfortably, in outward respects. It will not be worth the while to accumulate property; that would be sure to go again. You must hire or squat somewhere, and raise but a small crop, and eat that soon. You must live within yourself, and depend upon yourself always tucked up and ready for a start, and not have many affairs. A man may grow rich in Turkey even, if he will be in all respects a good subject of the Turkish government. Confucius said: “If a state is governed by the principles of reason, poverty and misery are subjects of shame; if a state is not governed by the principles of reason, riches and honors are the subjects of shame.” No: until I want the protection of Massachusetts to be extended to me in some distant Southern port, where my liberty is endangered, or until I am bent solely on building up an estate at home by peaceful enterprise, I can afford to refuse allegiance to Massachusetts, and her right to my property and life. It costs me less in every sense to incur the penalty of disobedience to the State than it would to obey. I should feel as if I were worth less in that case.

Some years ago, the State met me in behalf of the Church, and commanded me to pay a certain sum toward the support of a clergyman whose preaching my father attended, but never I myself. “Pay,” it said, “or be locked up in the jail.” I declined to pay. But, unfortunately, another man saw fit to pay it. I did not see why the schoolmaster should be taxed to support the priest, and not the priest the schoolmaster; for I was not the State’s schoolmaster, but I supported myself by voluntary subscription. I did not see why the lyceum should not present its tax-bill, and have the State to back its demand, as well as the Church. However, at the request of the selectmen, I condescended to make some such statement as this in writing:— “Know all men by these presents, that I, Henry Thoreau, do not wish to be regarded as a member of any incorporated society which I have not joined.” This I gave to the town clerk; and he has it. The State, having thus learned that I did not wish to be regarded as a member of that church, has never made a like demand on me since; though it said that it must adhere to its original presumption that time. If I had known how to name them, I should then have signed off in detail from all the societies which I never signed on to; but I did not know where to find a complete list.

I have paid no poll-tax for six years. I was put into a jail once on this account, for one night; and, as I stood considering the walls of solid stone, two or three feet thick, the door of wood and iron, a foot thick, and the iron grating which strained the light, I could not help being struck with the foolishness of that institution which treated me as if I were mere flesh and blood and bones, to be locked up. I wondered that it should have concluded at length that this was the best use it could put me to, and had never thought to avail itself of my services in some way. I saw that, if there was a wall of stone between me and my townsmen, there was a still more difficult one to climb or break through before they could get to be as free as I was. I did not for a moment feel confined, and the walls seemed a great waste of stone and mortar. I felt as if I alone of all my townsmen had paid my tax. They plainly did not know how to treat me, but behaved like persons who are underbred. In every threat and in every compliment there was a blunder; for they thought that my chief desire was to stand the other side of that stone wall. I could not but smile to see how industriously they locked the door on my meditations, which followed them out again without let or hindrance, and they were really all that was dangerous. As they could not reach me, they had resolved to punish my body; just as boys, if they cannot come at some person against whom they have a spite, will abuse his dog. I saw that the State was half-witted, that it was timid as a lone woman with her silver spoons, and that it did not know its friends from its foes, and I lost all my remaining respect for it, and pitied it.

Thus the State never intentionally confronts a man’s sense, intellectual or moral, but only his body, his senses. It is not armed with superior wit or honesty, but with superior physical strength. I was not born to be forced. I will breathe after my own fashion. Let us see who is the strongest. What force has a multitude? They only can force me who obey a higher law than I. They force me to become like themselves. I do not hear of men being forced to live this way or that by masses of men. What sort of life were that to live? When I meet a government which says to me, “Your money or your life,” why should I be in haste to give it my money? It may be in a great strait, and not know what to do: I cannot help that. It must help itself; do as I do. It is not worth the while to snivel about it. I am not responsible for the successful working of the machinery of society. I am not the son of the engineer. I perceive that, when an acorn and a chestnut fall side by side, the one does not remain inert to make way for the other, but both obey their own laws, and spring and grow and flourish as best they can, till one, perchance, overshadows and destroys the other. If a plant cannot live according to its nature, it dies; and so a man.

The night in prison was novel and interesting enough. The prisoners in their shirt-sleeves were enjoying a chat and the evening air in the doorway, when I entered. But the jailer said, “Come, boys, it is time to lock up”; and so they dispersed, and I heard the sound of their steps returning into the hollow apartments. My room-mate was introduced to me by the jailer as “a first-rate fellow and a clever man.” When the door was locked, he showed me where to hang my hat, and how he managed matters there. The rooms were whitewashed once a month; and this one, at least, was the whitest, most simply furnished, and probably the neatest apartment in the town. He naturally wanted to know where I came from, and what brought me there; and, when I had told him, I asked him in my turn how he came there, presuming him to be an honest man, of course; and, as the world goes, I believe he was. “Why,” said he, “they accuse me of burning a barn; but I never did it.” As near as I could discover, he had probably gone to bed in a barn when drunk, and smoked his pipe there; and so a barn was burnt. He had the reputation of being a clever man, had been there some three months waiting for his trial to come on, and would have to wait as much longer; but he was quite domesticated and contented, since he got his board for nothing, and thought that he was well treated.

He occupied one window, and I the other; and I saw that if one stayed there long, his principal business would be to look out the window. I had soon read all the tracts that were left there, and examined where former prisoners had broken out, and where a grate had been sawed off, and heard the history of the various occupants of that room; for I found that even here there was a history and a gossip which never circulated beyond the walls of the jail. Probably this is the only house in the town where verses are composed, which are afterward printed in a circular form, but not published. I was shown quite a long list of verses which were composed by some young men who had been detected in an attempt to escape, who avenged themselves by singing them.

I pumped my fellow-prisoner as dry as I could, for fear I should never see him again; but at length he showed me which was my bed, and left me to blow out the lamp.

It was like travelling into a far country, such as I had never expected to behold, to lie there for one night. It seemed to me that I never had heard the town clock strike before, nor the evening sounds of the village; for we slept with the windows open, which were inside the grating. It was to see my native village in the light of the Middle Ages, and our Concord was turned into a Rhine stream, and visions of knights and castles passed before me. They were the voices of old burghers that I heard in the streets. I was an involuntary spectator and auditor of whatever was done and said in the kitchen of the adjacent village inn— a wholly new and rare experience to me. It was a closer view of my native town. I was fairly inside of it. I never had seen its institutions before. This is one of its peculiar institutions; for it is a shire town. I began to comprehend what its inhabitants were about.

In the morning, our breakfasts were put through the hole in the door, in small oblong-square tin pans, made to fit, and holding a pint of chocolate, with brown bread, and an iron spoon. When they called for the vessels again, I was green enough to return what bread I had left; but my comrade seized it, and said that I should lay that up for lunch or dinner. Soon after he was let out to work at haying in a neighboring field, whither he went every day, and would not be back till noon; so he bade me good-day, saying that he doubted if he should see me again.

When I came out of prison— for some one interfered, and paid that tax— I did not perceive that great changes had taken place on the common, such as he observed who went in a youth and emerged a tottering and gray-headed man; and yet a change had to my eyes come over the scene— the town, and State, and country— greater than any that mere time could effect. I saw yet more distinctly the State in which I lived. I saw to what extent the people among whom I lived could be trusted as good neighbors and friends; that their friendship was for summer weather only; that they did not greatly propose to do right; that they were a distinct race from me by their prejudices and superstitions, as the Chinamen and Malays are; that in their sacrifices to humanity they ran no risks, not even to their property; that after all they were not so noble but they treated the thief as he had treated them, and hoped, by a certain outward observance and a few prayers, and by walking in a particular straight though useless path from time to time, to save their souls. This may be to judge my neighbors harshly; for I believe that many of them are not aware that they have such an institution as the jail in their village.

It was formerly the custom in our village, when a poor debtor came out of jail, for his acquaintances to salute him, looking through their fingers, which were crossed to represent the grating of a jail window, “How do ye do?” My neighbors did not thus salute me, but first looked at me, and then at one another, as if I had returned from a long journey. I was put into jail as I was going to the shoemaker’s to get a shoe which was mended. When I was let out the next morning, I proceeded to finish my errand, and, having put on my mended shoe, joined a huckleberry party, who were impatient to put themselves under my conduct; and in half an hour— for the horse was soon tackled— was in the midst of a huckleberry field, on one of our highest hills, two miles off, and then the State was nowhere to be seen.

This is the whole history of “My Prisons.”

I have never declined paying the highway tax, because I am as desirous of being a good neighbor as I am of being a bad subject; and as for supporting schools, I am doing my part to educate my fellow-countrymen now. It is for no particular item in the tax-bill that I refuse to pay it. I simply wish to refuse allegiance to the State, to withdraw and stand aloof from it effectually. I do not care to trace the course of my dollar, if I could, till it buys a man or a musket to shoot one with— the dollar is innocent— but I am concerned to trace the effects of my allegiance. In fact, I quietly declare war with the State, after my fashion, though I will still make what use and get what advantage of her I can, as is usual in such cases.

If others pay the tax which is demanded of me, from a sympathy with the State, they do but what they have already done in their own case, or rather they abet injustice to a greater extent than the State requires. If they pay the tax from a mistaken interest in the individual taxed, to save his property, or prevent his going to jail, it is because they have not considered wisely how far they let their private feelings interfere with the public good.

This, then, is my position at present. But one cannot be too much on his guard in such a case, lest his action be biased by obstinacy or an undue regard for the opinions of men. Let him see that he does only what belongs to himself and to the hour.

I think sometimes, Why, this people mean well, they are only ignorant; they would do better if they knew how: why give your neighbors this pain to treat you as they are not inclined to? But I think again, This is no reason why I should do as they do, or permit others to suffer much greater pain of a different kind. Again, I sometimes say to myself, When many millions of men, without heat, without ill will, without personal feeling of any kind, demand of you a few shillings only, without the possibility, such is their constitution, of retracting or altering their present demand, and without the possibility, on your side, of appeal to any other millions, why expose yourself to this overwhelming brute force? You do not resist cold and hunger, the winds and the waves, thus obstinately; you quietly submit to a thousand similar necessities. You do not put your head into the fire. But just in proportion as I regard this as not wholly a brute force, but partly a human force, and consider that I have relations to those millions as to so many millions of men, and not of mere brute or inanimate things, I see that appeal is possible, first and instantaneously, from them to the Maker of them, and, secondly, from them to themselves. But if I put my head deliberately into the fire, there is no appeal to fire or to the Maker of fire, and I have only myself to blame. If I could convince myself that I have any right to be satisfied with men as they are, and to treat them accordingly, and not according, in some respects, to my requisitions and expectations of what they and I ought to be, then, like a good Mussulman and fatalist, I should endeavor to be satisfied with things as they are, and say it is the will of God. And, above all, there is this difference between resisting this and a purely brute or natural force, that I can resist this with some effect; but I cannot expect, like Orpheus, to change the nature of the rocks and trees and beasts.

I do not wish to quarrel with any man or nation. I do not wish to split hairs, to make fine distinctions, or set myself up as better than my neighbors. I seek rather, I may say, even an excuse for conforming to the laws of the land. I am but too ready to conform to them. Indeed, I have reason to suspect myself on this head; and each year, as the tax-gatherer comes round, I find myself disposed to review the acts and position of the general and State governments, and the spirit of the people, to discover a pretext for conformity.

“We must affect our country as our parents,

And if at any time we alienate

Our love or industry from doing it honor,

We must respect effects and teach the soul

Matter of conscience and religion,

And not desire of rule or benefit.”

[George Peele Battle of Alcazar ]

I believe that the State will soon be able to take all my work of this sort out of my hands, and then I shall be no better a patriot than my fellow-countrymen. Seen from a lower point of view, the Constitution, with all its faults, is very good; the law and the courts are very respectable; even this State and this American government are, in many respects, very admirable, and rare things, to be thankful for, such as a great many have described them; but seen from a point of view a little higher, they are what I have described them; seen from a higher still, and the highest, who shall say what they are, or that they are worth looking at or thinking of at all?

However, the government does not concern me much, and I shall bestow the fewest possible thoughts on it. It is not many moments that I live under a government, even in this world. If a man is thought-free, fancy-free, imagination-free, that which is not never for a long time appearing to be to him, unwise rulers or reformers cannot fatally interrupt him.

I know that most men think differently from myself; but those whose lives are by profession devoted to the study of these or kindred subjects content me as little as any. Statesmen and legislators, standing so completely within the institution, never distinctly and nakedly behold it. They speak of moving society, but have no resting-place without it. They may be men of a certain experience and discrimination, and have no doubt invented ingenious and even useful systems, for which we sincerely thank them; but all their wit and usefulness lie within certain not very wide limits. They are wont to forget that the world is not governed by policy and expediency. Webster never goes behind government, and so cannot speak with authority about it. His words are wisdom to those legislators who contemplate no essential reform in the existing government; but for thinkers, and those who legislate for all time, he never once glances at the subject. I know of those whose serene and wise speculations on this theme would soon reveal the limits of his mind’s range and hospitality. Yet, compared with the cheap professions of most reformers, and the still cheaper wisdom and eloquence of politicians in general, his are almost the only sensible and valuable words, and we thank Heaven for him. Comparatively, he is always strong, original, and, above all, practical. Still, his quality is not wisdom, but prudence. The lawyer’s truth is not Truth, but consistency or a consistent expediency. Truth is always in harmony with herself, and is not concerned chiefly to reveal the justice that may consist with wrong-doing. He well deserves to be called, as he has been called, the Defender of the Constitution. There are really no blows to be given by him but defensive ones. He is not a leader, but a follower. His leaders are the men of ’87— “I have never made an effort,” he says, “and never propose to make an effort; I have never countenanced an effort, and never mean to countenance an effort, to disturb the arrangement as originally made, by which the various States came into the Union.” Still thinking of the sanction which the Constitution gives to slavery, he says, “Because it was a part of the original compact— let it stand.” Notwithstanding his special acuteness and ability, he is unable to take a fact out of its merely political relations, and behold it as it lies absolutely to be disposed of by the intellect— what, for instance, it behooves a man to do here in America today with regard to slavery— but ventures, or is driven, to make some such desperate answer as the following, while professing to speak absolutely, and as a private man— from which what new and singular code of social duties might be inferred? “The manner,” says he, “in which the governments of those States where slavery exists are to regulate it is for their own consideration, under their responsibility to their constituents, to the general laws of propriety, humanity, and justice, and to God. Associations formed elsewhere, springing from a feeling of humanity, or any other cause, have nothing whatever to do with it. They have never received any encouragement from me, and they never will.”

They who know of no purer sources of truth, who have traced up its stream no higher, stand, and wisely stand, by the Bible and the Constitution, and drink at it there with reverence and humility; but they who behold where it comes trickling into this lake or that pool, gird up their loins once more, and continue their pilgrimage toward its fountain-head.

No man with a genius for legislation has appeared in America. They are rare in the history of the world. There are orators, politicians, and eloquent men, by the thousand; but the speaker has not yet opened his mouth to speak who is capable of settling the much-vexed questions of the day. We love eloquence for its own sake, and not for any truth which it may utter, or any heroism it may inspire. Our legislators have not yet learned the comparative value of free trade and of freedom, of union, and of rectitude, to a nation. They have no genius or talent for comparatively humble questions of taxation and finance, commerce and manufactures and agriculture. If we were left solely to the wordy wit of legislators in Congress for our guidance, uncorrected by the seasonable experience and the effectual complaints of the people, America would not long retain her rank among the nations. For eighteen hundred years, though perchance I have no right to say it, the New Testament has been written; yet where is the legislator who has wisdom and practical talent enough to avail himself of the light which it sheds on the science of legislation?

The authority of government, even such as I am willing to submit to— for I will cheerfully obey those who know and can do better than I, and in many things even those who neither know nor can do so well— is still an impure one: to be strictly just, it must have the sanction and consent of the governed. It can have no pure right over my person and property but what I concede to it. The progress from an absolute to a limited monarchy, from a limited monarchy to a democracy, is a progress toward a true respect for the individual. Even the Chinese philosopher was wise enough to regard the individual as the basis of the empire. Is a democracy, such as we know it, the last improvement possible in government? Is it not possible to take a step further towards recognizing and organizing the rights of man? There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly. I please myself with imagining a State at least which can afford to be just to all men, and to treat the individual with respect as a neighbor; which even would not think it inconsistent with its own repose if a few were to live aloof from it, not meddling with it, nor embraced by it, who fulfilled all the duties of neighbors and fellow-men. A State which bore this kind of fruit, and suffered it to drop off as fast as it ripened, would prepare the way for a still more perfect and glorious State, which also I have imagined, but not yet anywhere seen.

(1849)

This text is sometimes presented under the title On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. Its original title is Resistance to Civil Government.

Civil Disobedience by Henry David Thoreau

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Henry David Thoreau, MONTAIGNE, MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST

STICHTING PERDU AMSTERDAM

Zondag 1 mei 2011

Effectief weigeren

Over Civil Disobedience van H. D. Thoreau

Aanvang: 15.00 uur

Zaal open: 14.30 uur

Entree: 7 euro / 5 euro (studenten of vriendenpas)

Met Astrid Lampe, Robin Stokrom, e.a.

In 1846 bracht de Amerikaanse dichter, schrijver en essayist Henry David Thoreau een nacht in de gevangenis door. Zijn misdaad: belastingontduiking. Hij had geen belasting betaald omdat hij weigerde de staat Massachussetts te steunen, die in zijn ogen fundamenteel onrechtvaardig was wegens zijn positie inzake slavernij en medeverantwoordelijkheid voor de Amerikaans-Mexicaanse oorlog. De gevangenneming zelf duurde maar kort omdat de volgende dag een familielid het verschuldigde bedrag voldeed, maar in 1849 publiceerde Thoreau het essay “Resistance to Civil Government”, beter bekend als “Civil Disobedience”. Met dit essay en de stevige stellingnames over weigering van staatsonrecht kreeg Thoreau in de loop der jaren grote invloed op het politieke denken, en werd hij een belangrijk inspirator voor veel verzetsbewegingen. Het is vooral die publicatie die zijn eerdere verzet effectief maakt als kritische positie.

De kwestie van burgerlijke ongehoorzaamheid en onrechtvaardige overheid is altijd actueel gebleven. Over het eerste is in Nederland de laatste jaren discussie geweest (denk aan de Duyvendak-affaire); en er heerst nu een regering die in veler ogen moreel onaanvaardbaar is. Reden om opnieuw terug te grijpen op Thoreau’s tekst en het thema dat hij erin aansnijdt.

Is heden ten dage een dergelijk verzet nodig? Is het mogelijk om in een verondersteld permissieve liberale maatschappij te weigeren mee te doen, en hoe? En op welke manier kan zo’n weigering überhaupt waarneembaar worden binnen het maatschappelijke discours, en zijn potentie als kritische daad actief ontplooien?

Stichting Perdu

Kloveniersburgwal 86

1012 CZ Amsterdam

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Henry David Thoreau, Lampe, Astrid, MONTAIGNE, MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST

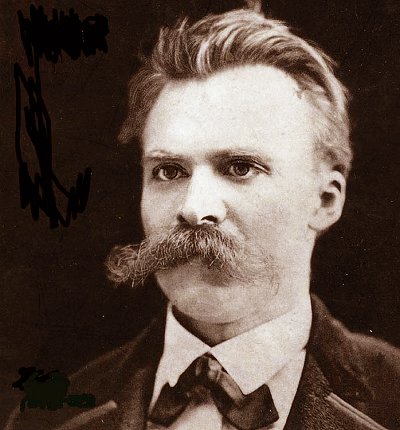

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche

(1844-1900)

Idyllen aus Messina

Die kleine Hexe

So lang noch hübsch mein Leibchen,

Lohnt sichs schon, fromm zu sein.

Man weiss, Gott liebt die Weibchen,

Die hübschen obendrein.

Er wird’s dem art’gen Mönchlein

Gewisslich gern verzeihn,

Dass er, gleich manchem Mönchlein,

So gern will bei mir sein.

Kein grauer Kirchenvater!

Nein, jung noch und oft roth,

Oft gleich dem grausten Kater

Voll Eifersucht und Noth!

Ich liebe nicht die Greise,

Er liebt die Alten nicht:

Wie wunderlich und weise

Hat Gott dies eingericht!

Die Kirche weiss zu leben,

Sie prüft Herz und Gesicht.

Stäts will sie mir vergeben: –

Ja wer vergiebt mir nicht!

Man lispelt mit dem Mündchen,

Man knixt und geht hinaus

Und mit dem neuen Sündchen

Löscht man das alte aus.

Gelobt sei Gott auf Erden,

Der hübsche Mädchen liebt

Und derlei Herzbeschwerden

Sich selber gern vergiebt!

So lang noch hübsch mein Leibchen,

Lohnt sich’s schon, fromm zu sein:

Als altes Wackelweibchen

Mag mich der Teufel frein!

kempis.nl # kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Friedrich Nietzsche, Nietzsche

Voltaire

(François Marie Arouet, 1694-1778)

Les Vous et les Tu

Philis, qu’est devenu ce temps

Où, dans un fiacre promenée,

Sans laquais, sans ajustements,

De tes grâces seules ornée,

Contente d’un mauvais soupé

Que tu changeais en ambroisie,

Tu te livrais, dans ta folie,

A l’amant heureux et trompé

Qui t’avait consacré sa vie ?

Le ciel ne te donnait alors,

Pour tout rang et pour tous trésors,

Que les agréments de ton âge,

Un coeur tendre, un esprit volage,

Un sein d’albâtre, et de beaux yeux.

Avec tant d’attraits précieux,

Hélas ! qui n’eût été friponne ?

Tu le fus, objet gracieux !

Et (que l’Amour me le pardonne !)

Tu sais que je t’en aimais mieux.

Ah ! madame ! que votre vie

D’honneurs aujourd’hui si remplie,

Diffère de ces doux instants !

Ce large suisse à cheveux blancs,

Qui ment sans cesse à votre porte,

Philis, est l’image du Temps ;

On dirait qu’il chasse l’escorte

Des tendres Amours et des Ris ;

Sous vos magnifiques lambris

Ces enfants tremblent de paraître.

Hélas ! je les ai vus jadis

Entrer chez toi par la fenêtre,

Et se jouer dans ton taudis.

Non, madame, tous ces tapis

Qu’a tissus la Savonnerie,

Ceux que les Persans ont ourdis,

Et toute votre orfèvrerie,

Et ces plats si chers que Germain

A gravés de sa main divine,

Et ces cabinets où Martin

A surpassé l’art de la Chine ;

Vos vases japonais et blancs,

Toutes ces fragiles merveilles ;

Ces deux lustres de diamants

Qui pendent à vos deux oreilles ;

Ces riches carcans, ces colliers,

Et cette pompe enchanteresse,

Ne valent pas un des baisers

Que tu donnais dans ta jeunesse.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive U-V, MONTAIGNE, Voltaire

.jpg)

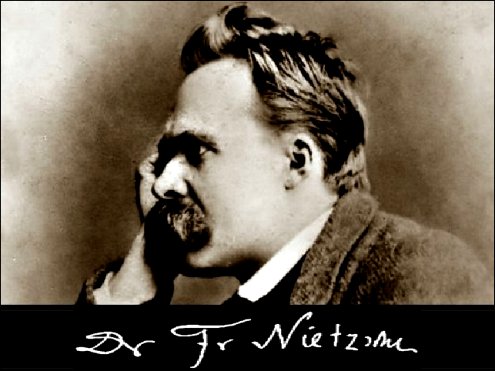

Friedrich Nietzsche

(1844-1900)

Das nächtliche Geheimniss

Gestern Nachts, als Alles schlief,

Kaum der Wind mit ungewissen

Seufzern durch die Gassen lief,

Gab mir Ruhe nicht das Kissen,

Noch der Mohn, noch, was sonst tief

Schlafen macht – ein gut Gewissen.

Endlich schlug ich mir den Schlaf

Aus dem Sinn und lief zum Strande.

Mondhell war’s und mild – ich traf

Mann und Kahn auf warmem Sande,

Schläfrig beide, Hirt und Schaf: –

Schläfrig stiess der Kahn vom Lande.

Eine Stunde, leicht auch zwei,

Oder war’s ein Jahr? – da sanken

Plötzlich mir Sinn und Gedanken

In ein ew’ges Einerlei,

Und ein Abgrund ohne Schranken

That sich auf: – da war’s vorbei! –

Morgen kam: auf schwarzen Tiefen

Steht ein Kahn und ruht und ruht – –

Was geschah? so riefs, so riefen

Hundert bald – was gab es? Blut? –

Nichts geschah! Wir schliefen, schliefen

Alle – ach, so gut! so gut!

Friedrich Nietzsche poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Friedrich Nietzsche, Nietzsche

Thomas a Kempis

(1380-1471)

De navolging van Christus

Boek 2, Hoofdstuk 3

Over de vreedzame mens

1. Stel uzelf eerst in vrede, en dan zult gij anderen ook tot vrede kunnen stichten.

Een vredelievend mens doet meer goed dan een groot geleerde.

Een driftig mens maakt van het goed kwaad en gelooft licht aan het kwaad.

Een goed, vreedzaam mens keert alles ten goede.

Die wel tevreden is, heeft van niemand kwaad vermoeden, maar die slecht tevreden en ontroerd is, wordt door veel kwade vermoedens gekweld; hij is niet gerust, en hij verontrust anderen.

Hij zegt dikwijls wat hij niet moest zeggen, en laat achterwege wat hij zou moeten doen.

Hij let op wat de anderen verplicht zijn te doen, en hij verzuimt zijn eigen plicht.

Heb dan eerst ijver voor uzelf, en dan zult gij met reden ook uw naaste tot ijver kunnen aansporen.

2. Gij weet uw eigen daden wel te verschonen, en de verontschuldigingen van anderen wilt gij niet aannemen.

Het ware rechtvaardiger uzelf te beschuldigen, en uw broeder te verschonen.

Wilt gij dat men uw gebreken verdrage, verdraag die van anderen.

Zie hoe ver gij nog van de ware liefde en ootmoed verwijderd zijt, waardoor men zich nooit vergramt of nooit verontwaardigd is dan tegen zichzelf.

Het is geen grote deugd, met goede en zachtmoedige mensen vreedzaam te leven, dit behaagt natuurlijk aan alle mensen, want iedereen is gaarne in vrede en bemint ook het meest die met hem overeenkomen.

Maar in vrede kunnen leven met stuurse, boosaardige en ongeregelde mensen, of met die, welke ons dwarsbomen, dit is een grote gave en een grootmoedig en hoogst loffelijk bedrijf.

3. Daar zijn er, die met zichzelf, en ook met anderen in vrede zijn.

En daar zijn er, die zelf geen vrede hebben, en die anderen in vrede niet laten; zij zijn voor de anderen lastig, maar nog veel lastiger voor zichzelf.

En daar zijn er, die zichzelf in vrede behouden, en ook anderen trachten tot vrede terug te brengen.

Nochtans geheel onze vrede, in dit ellendig leven, bestaat in meer ootmoedige lijdzaamheid dan in ‘t niet gevoelen van tegenheden.

Wie best weet te lijden, zal de meeste vrede hebben; hij is overwinnaar van zichzelf, hij is meester van de wereld, vriend van Jezus Christus en erfgenaam van de hemel.

Oefening

Neemt men de grondregel van de schrijver aan dat de ware vrede eerder bestaat in de ootmoedige onderwerping aan wat ons tegenstaat, dan in geen tegenstand te ontmoeten, zo moeten wij besluiten, de vrede in de tegenspraak en de rust in de onheilen te zoeken, en zulks met al het kwaad, dat men ons kan aandoen of dat men van ons zou kunnen zeggen, met een geduld en een zoetaardigheid te verdragen, die alle vervolging overwint. Een ziel, die waarlijk ootmoedig is, weet op niemand, dan op haarzelf iets te zeggen; zij verontschuldigt anderen en beschuldigt zichzelf, en zij is nooit vergramd dan op haarzelf. Mijn voornemen is dus, in vrede te leven -met God: door Hem in alles gehoorzaam te wezen; – met mijn evennaaste: door niemands gedrag te berispen, en mij met de zaken van anderen niet te bemoeien; – met mijzelf: door in alle gelegenheden de neigingen en de tegenstrijdigheden van mijn hart te bevechten en te overwinnen.

Gebed

Heer, Gij hebt door uw profeet gezegd: Betracht de vrede en jaag hem na, dat is te zeggen laat niet na hem te zoeken tot gij die gevonden zult hebben. Niemand dan Gij, o Jezus, kan mij de vrede geven, aangezien Gij alleen mij de vrede met uw Vader op het kruis verschaft en mij met Hem verzoend hebt. Reeds lang heb ik getracht met U, met mijn naaste en met mijzelf in vrede te leven; maar mijn ontrouw, gevoeligheid en haastigheid – die gedurige oorzaken van de onrust van mijn ziel – beletten mij die vrede te genieten. O Zaligmaker, die de tempeesten hebt gestild, en die over de winden der lucht en over de baren der zee gebiedt, stil ook de bewegingen van mijn hart, dat in U alleen een ware rust kan vinden. Maak, dat het in alles aan uw heilige wil onderworpen zij, en dat het de vrede en de rust vinde in alles te doen, in alles te lijden, wat Gij wilt. Amen.

Thomas a Kempis:

Over de vreedzame mens

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, MONTAIGNE, Thomas a Kempis

.jpg)

Friedrich Nietzsche

(1844-1900)

Dichters Berufung

Als ich jüngst, mich zu erquicken,

Unter dunklen Bäumen sass,

Hört’ ich ticken, leise ticken,

Zierlich, wie nach Takt und Maass.

Böse wurd’ ich, zog Gesichter, –

Endlich aber gab ich nach,

Bis ich gar, gleich einem Dichter,

Selber mit im Tiktak sprach.

Wie mir so im Verse-Machen

Silb’ um Silb’ ihr Hopsa sprang,

Musst’ ich plötzlich lachen, lachen

Eine Viertelstunde lang.

Du ein Dichter? Du ein Dichter?

Steht’s mit deinem Kopf so schlecht?

– “Ja, mein Herr, Sie sind ein Dichter”

Achselzuckt der Vogel Specht.

Wessen harr’ ich hier im Busche?

Wem doch laur’ ich Räuber auf?

Ist’s ein Spruch? Ein Bild? Im Husche

Sitzt mein Reim ihm hintendrauf.

Was nur schlüpft und hüpft, gleich sticht der