Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (11)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK II

5

A problem which I find it far more difficult to solve is this: how in the world Giorgio Mirelli, who would fly with such impatience from every complication, can have lost himself to this woman, to the point of laying down his life on her account.

Almost all the details are lacking that would enable me to solve this problem, and I have said already that I have no more than a summary report of the drama.

I know from various sources that the Nestoroff, at Capri, when Giorgio Mirelli saw her for the first time, was in distinctly bad odour, and was treated with great diffidence by the little Russian colony, which for some years past has been settled upon that island.

Some even suspected her of being a spy, perhaps because she, not very prudently, had introduced herself as the widow of an old conspirator, who had died some years before her coming to Capri, a refugee in Berlin. It appears that some one wrote for information, both to Berlin and to Petersburg, with regard to her and to this unknown conspirator, and that it came to light that a certain Nikolai Nestoroff had indeed been for some years in exile in Berlin, and had died there, but without ever having given anyone to understand that he was exiled for political reasons. It appears to have become known also that this Nikolai Nestoroff had taken her, as a little girl, from the streets, in one of the poorest and most disreputable quarters of Petersburg, and, after having her educated, had married her; and then, reduced by his vices to the verge of starvation had lived upon her, sending her out to sing in music-halls of the lowest order, until, with the police on his track, he had made his escape, alone, into Germany. But the Nestoroff, to my knowledge, indignantly denies all these stories.

That she may have complained privately to some one of the ill-treatment, not to say the cruelty she received from her girlhood at the hands of this old man is quite possible; but she does not say that he lived upon her; she says rather that, of her own accord, obeying the call of her passion, and also, perhaps, to supply the necessities of life, having overcome his opposition, she took to acting in the provinces, a-c-t-i-n-g, mind, on the legitimate stage; and that then, her husband having fled from Russia for political reasons and settled in Berlin, she, knowing him to be in frail health and in need of attention, taking pity on him, had joined him there and remained with him till his death. What she did then, in Berlin, as a widow, and afterwards in Paris and Vienna, cities to which she often refers, shewing a thorough knowledge of their life and customs, she neither says herself nor certainly does anyone ever venture to ask her.

For certain people, for innumerable people, I should say, who are incapable of seeing anything but themselves, love of humanity often, if not always, means nothing more than being pleased with themselves.

Thoroughly pleased with himself, with his art, with his studies of landscape, must Giorgio Mirelli, unquestionably, have been in those days at Capri.

Indeed–and I seem to have said this before–his habitual state of mind was one of rapture and amazement. Given such a state of mind, it is easy to imagine that this woman did not appear to him as she really was, with the needs that she felt, wounded, scourged, poisoned by the distrust and evil gossip that surrounded her; but in the fantastic transfiguration that he at once made of her, and illuminated by the light in which he beheld her. For him feelings must take the form of colours, and, perhaps, entirely engrossed in his art, he had no other feeling left save for colour. All the impressions that he formed of her were derived exclusively, perhaps, from the light which he shed upon her; impressions, therefore, that were felt by him alone. She need not, perhaps could not participate in them. Now, nothing irritates us more than to be shut out from an enjoyment, vividly present before our eyes, round about us, the reason of which we can neither discover nor guess. But even if Giorgio Mirelli had told her of his enjoyment, he could not have conveyed it to her mind. It was a joy felt by him alone, and proved that he too, in his heart, prayed and wished for nothing else of her than her body; not, it is true, like other men, with base intent; but even this, in the long run–if you think it over carefully–could not but increase the woman’s irritation. Because, if the failure to derive any assistance, in the maddening uncertainties of her spirit, from the many who saw and desired nothing in her save her body, to satisfy on it the brutal appetite of the senses, filled her with anger and disgust; her anger with the one man, who also desired her body and nothing more; her body, but only to extract from it an ideal and absolutely self-sufficient pleasure, must have been all the stronger, in so far as every provocative of disgust was entirely lacking, and must have rendered more difficult, if not absolutely futile, the vengeance which she was in the habit of wreaking upon other people. An angel, to a woman, is always more irritating than a beast.

I know from all Giorgio Mirelli’s artist friends in Naples that he was spotlessly chaste, not because he did not know how to make an impression upon women, but because he instinctively avoided every vulgar distraction.

To account for his suicide, which beyond question was largely due to the Nestoroff, we ought to assume that she, not cared for, not helped, and irritated to madness, in order to be avenged, must with the finest and subtlest art have contrived that her body should gradually come to life before his eyes, not for the delight of his eyes alone; and that, when she saw him, like all the rest, conquered and enslaved, she forbade him, the better to taste her revenge, to take any other pleasure from her than that with which, until then, he had been content, as the only one desired, because the only one worthy of him.

‘We ought’, I say, to assume this, but only if we wish to be ill-natured. The Nestoroff might say, and perhaps does say, that she did nothing to alter that relation of pure friendship which had grown up between herself and Mirelli; so much so that when he, no longer contented with that pure friendship, more impetuous than ever owing to the severe repulse with which she met his advances, yet, to obtain his purpose, offered to marry her, she struggled for a long time–and this is true; I learned it on good authority–to dissuade him, and proposed to leave Capri, to disappear; and in the end remained there only because of his acute despair.

But it is true that, if we wish to be ill-natured, we may also be of opinion that both the early repulse and the later struggle and threat and attempt to leave the island, to disappear, were perhaps so many artifices carefully planned and put into practice to reduce this young man to despair after having seduced him, and to obtain from him all sorts of things which otherwise he would never, perhaps, have conceded to her. Foremost among them, that she should be introduced as his future bride at the Villa by Sorrento to that dear Granny, to that sweet little sister, of whom he had spoken to her, and to the sister’s betrothed.

It seems that he, Aldo Nuti, more than, the two women, resolutely opposed this claim. Authority and power to oppose and to prevent this marriage he did not possess, for Giorgio was now his own master, free to act as he chose, and considered that he need no longer give an account of himself to anyone; but that he should bring this woman to the house and place her in contact with his sister, and expect the latter to welcome her and to treat her as a sister, this, by Jove, he could and must oppose, and oppose it he did with all his strength. But were they, Granny Rosa and Duccella, aware what sort of woman this was that Giorgio proposed to bring to the house and to marry? A Russian adventuress, an actress, if not something worse! How could he allow such a thing, how not oppose it with all his strength?

Again “with all his strength”… Ah, yes, who knows how hard Granny Rosa and Duccella had to fight in order to overcome, little by little, by their sweet and gentle persuasion, all the strength of Aldo Nuti. How could they have imagined what was to become of that strength at the sight of Varia Nestoroff, as soon as she set foot, timid, ethereal and smiling, in the dear villa by Sorrento!

Perhaps Giorgio, to account for the delay which Granny Rosa and Duccella shewed in answering, may have said to the Nestoroff that this delay was due to the opposition “with all his strength” of his sister’s future husband; so that the Nestoroff felt the temptation to measure her own strength against this other, at once, as soon as she set foot in the villa. I know nothing! I know that Aldo Nuti was drawn in as though into a whirlpool and at once carried away like a wisp of straw by passion for this woman.

I do not know him. I saw him as a boy, once only, when I was acting as Giorgio’s tutor, and he struck me as a fool. This impression of mine does not agree with what Mirelli said to me about him, on my return from Liege, namely that he was ‘complicated’. Nor does what I have heard from other people, with regard to him correspond in the least with this first impression, which however has irresistibly led me to speak of him according to the idea that I had formed of him from it. I must, really, have been mistaken. Duccella found it possible to love him! And this, to my mind, does more than anything else to prove me in the wrong. But we cannot control our impressions. He may be, as people tell me, a serious young man, albeit of a most ardent temperament; for me, until I see him again, he will remain that fool of a boy, with the baron’s coronet on his handkerchiefs and portfolios, the young gentleman who ‘would so love to become an actor’.

He became one, and not by way of make-believe, with the Nestoroff, at Giorgio Mirelli’s expense. The drama was unfolded at Naples, shortly after the Nestoroff’s introduction and brief visit to the house at Sorrento. It seems that Nuti returned to Naples with the engaged couple, after that brief visit, to help the inexperienced Giorgio and her who was not yet familiar with the town, to set their house in order before the wedding.

Perhaps the drama would not have happened, or would have had a different ending, had it not been for the complication of Duccella’s engagement to, or rather her love for Nuti. For this reason Giorgio Mirelli was obliged to concentrate on himself the violence of the unendurable horror that overcame him at the sudden discovery of his betrayal.

Aldo Nuti rushed from Naples like a madman before there arrived from Sorrento at the news of Giorgio’s suicide Granny Rosa and Duccella.

Poor Duccella, poor Granny Rosa! The woman who from thousands and thousands of miles away came to bring confusion and death into your little house where with the jasmines bloomed the most innocent of idylls, I have her here, now, in front of my machine, every day; and, if the news I have heard from Polacco be true, I shall presently have him here as well, Aldo Nuti, who appears to have heard that the Nestoroff is leading lady with the Kosmograph.

I do not know why, my heart tells me that, as I turn the handle of this photographic machine, I am destined to carry out both your revenge and your poor Giorgio’s, dear Duccella, dear Granny Rosa!

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (11)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

(to be continued)

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

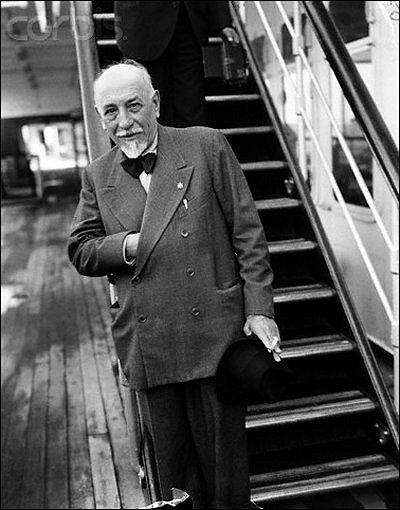

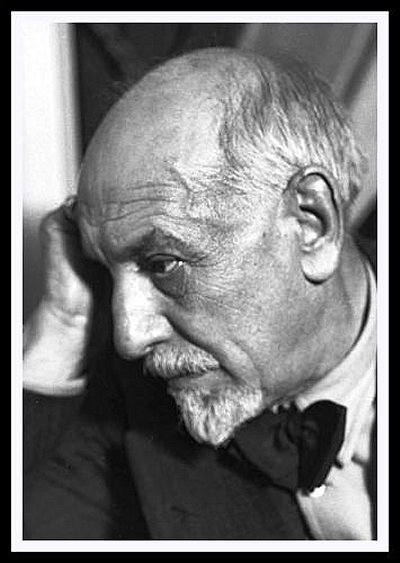

L u i g i P i r a n d e l l o

(1867-1936)

Tormenti

Quando in croce Gesú l’anima rese,

tutta, per un momento,

su la terra la vita si sospese,

sospese anche l’inferno ogni tormento.

Sisifo che per l’erta maledetta

avea sospinto il masso

fin su l’aspra del colle aguzza vetta,

donde tuttor riprecipita al basso,

fermo, lassú, starsi d’un tratto il vede:

stupefatto, in un oh!

fermo, di sasso, anch’egli resta, e fede

al prodigio prestar non sa, non può.

Si guarda attorno, una e due volte scuote

il macigno che sta;

vi siede e, con le pugna su le gote,

poi domanda a se stesso: – «E or che si fa?» –

Ma sotto, ecco, gli ruzzola il fatale

sasso di nuovo; ratto

balza egli in pie’, lo segue, e: – «Manco male! –

dice. – Almeno cosí, via, m’arrabatto». –

E, mentre sú per l’erta novamente

contro il masso si slancia,

tra le doglie piú là, Tantalo sente

gridare urlare: – «Ahi Dio! Ahi Dio! la pancia!» –

Aggirandosi come una bufera,

satollo, il poveretto,

in quella tregua momentanea s’era

di tutto quanto il suo crudel banchetto.

Ed or gemeva: – «Non lo farò piú!

Beato chi desia

e nulla ottiene mai! Grazia, Gesú!

Sia benedetta la condanna mia!» –

Leggendo la Storia

Sú, allegra, allegra, cara mia! Mi pare

che tu la prenda un po’ troppo sul serio.

Delitti, infamie, sí, senza criterio,

impudicizie da strasecolare;

ma gajo papa era Alessandro Borgia,

tranquillo e ingenuo nelle sue nequizie;

tranne quel della donna, senza vizi, e

sobrio, anzi frugale in mezzo all’orgia.

Ebbe per l’oro, è vero, anima lurca,

ma lo spendeva poi, tutto, tal quale.

Né per un papa infin la vedo male

che andasse a caccia vestito alla turca.

Di piú d’un figlio con Vannozza reo,

diede a Vannozza sua piú d’un marito;

ma l’ultimo, il Canal, bravo erudito:

il Polizian gli dedicò l’Orfeo,

Quanti vitelli con moderna clava

accoppa l’uomo e se li mangia? Orbene,

papa Alessandro, accoppator dabbene,

i suoi nemici, non se li mangiava.

Dunque, non mi seccar! Parole amare,

serio comento a questa fantocciata

della vita? Va’ là. Carta sprecata.

Ridi meglio, narrando, e lascia fare.

Primavera dei Terrazzi

La mia vicina, sul mattin d’aprile,

compresa ancora del tepor del letto,

esce al terrazzo, e al sol primaverile

spiega i tesori del ricolmo petto.

Ella ha piú grazia, la vicina, in quella

acconciatura che le cangia aspetto:

un camicino bianco e una gonnella

di panno lano oscura. La saluto

dal mio poggiolo dirimpetto, ed ella,

lieve inchinando il capo riccioluto,

mi risponde; poi viene al pilastrino,

su cui ride snasato un fauno arguto,

e dice: – «Come mai, caro vicino?

siete voi? sogno ancora? o com’è andata?

qual gallo v’ha cantato il mattutino?» –

Cosí, tra i fior, su la balaustrata,

dei vasi ben disposti e con amore

coltivati da lei lungo l’annata,

un grande anch’ella pare e vivo fiore;

anzi, lei sola, un fiore. A quel giardino,

giro giro, che calci di gran cuore

darei! parmi ogni vaso un cervellino

di moderno romantico poeta

che levi dal suo fango un inno fino

tra il cessin le pillaccole e la creta

per dir che piú non ama e piú non spera

alla stagion che tutto il mondo allieta.

Oh dei terrazzi magra primavera,

sciocca di nuove rime fioritura!

Mi duol che voi, maestra giardiniera,

ve ne prendiate cosí assidua cura.

Codesti fiori dall’olezzo ingrato

non vi sembrano sforzi di natura?

Due tartarughe, intanto, senza fiato,

s’inseguono sui pie’ sbiechi, in amore,

raspando il piano d’asfalto bruciato.

Cara vicina, fatemi il favore

di rivoltarle su la scaglia al sole:

non hanno alcun riguardo, alcun pudore,

brutte rocciose sceme bestiole;

sono lí lí per fare atto villano,

mentre che noi facciam solo parole:

le vedremo armeggiar nel vuoto, invano.

Luigi Pirandello: Poesia

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Luigi Pirandello, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature