Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

Comte Nikolai de Godemiché

(1878-1935)

Comte Nikolai de Godemiché (1878-1935) stamt af van het kind dat op wonderbaarlijke wijze werd geboren uit een overleden en reeds begraven moeder. Dieven hadden het graf geschonden en ontdekten dat de dode vrouw in barensweeën verkeerde. Ze namen het kind mee en begroeven de vrouw opnieuw. Heinrich Heine doet verslag over deze bizarre gebeurtenis in zijn verhaal ‘Florentijnse nachten’.

De voorvader van Nikolai werd bijwijze van zwijggeld een adellijke titel toegekend om zijn afkomst te verdoezelen als bastaardzoon van een telg uit een bekende Duits-Franse bankiersfamilie. Oorspronkelijk was Comte de Godemiché de titel van een libertijn die zijn huurdames placht te ontvangen in een gecapitonneerde kamer opdat het gillen voor de buitenwacht verborgen bleef. Het was een van de vele titels die vrij rolde door het werk van de guillotine in de nadagen van de Revolutie en als zodanig voor hergebruik in aanmerking kwam.

Op 57 jarige leeftijd wierp de aan alcohol en opium verslaafde Nikolai zich van de Notre Dame. Deze getalenteerde misantropische polyglot beheerste onder andere het Nederlands, de taal waarin hij schreef. Zijn literaire nalatenschap bestaat uit 19 wulpse gedichten.

Hij & Zij

Een eredienst voor erotiek

het vallen van haar lingerie

zijn bokkendrift is puur fysiek

haar blik verraadt hem haar ennui

dus basta met de symboliek

hij zet de puntjes op de i!

een eredienst voor erotiek

het parfum van haar blanke huid

hij windt haar op in zijn tragiek

met het getokkel van een luit

zij smelt voor deze symboliek

en spant haar lippen om het fruit!

(Comte Nikolai de Godemiché: Fauneske Verzen & Prozagedichten. Erotica. Uitgeverij Spleen Amsterdam, 2008, 2e druk)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Erotic literature

Jan Gielkens

Malloot

Wát moet iedere verzamelaar over zichzelf weten?!

Ik word wel een ‘fervent verzamelaar’ genoemd. Nu zeg ik altijd: ik verzamel niets, ik bewaar alleen het een en ander. Maar goed: er is een boek verschenen dat over mijn soort lijkt te gaan. Ik zeg ‘lijkt te gaan’, zodat u meteen weet welke tendens dit stukje heeft. Het boek heet Hebben en houden. Wat iedere verzamelaar en boekenliefhebber over zichzelf moet weten, het is geschreven door de socioloog Jaco Berveling en verschenen bij uitgeverij Aspekt in Soesterberg.

Zou ik dit boek hebben gekocht als ik het niet cadeau had gekregen? (Dankjewel, Joep!) Tijdens de Verzamelaarsjaarbeurs in Utrecht nog wel, waar de auteur zijn boeken zat te verkopen. Op het voor- en het achterplat van het boek staat dezelfde foto van een stapel boeken. En zo hoort dat als een boek onder andere over het verzamelen van boeken gaat.

Maar wat staan er voor boeken op Hebben en houden? Het zijn gloednieuwe boeken in elk geval, en ik kan een paar ruggen lezen: ‘Tyskland’ kan ik ontcijferen en een deel van een titel: ‘Jord och’. Het zijn dus Zweedse boeken. Heeft iemand bij de Ikea een Billy mét boeken gekocht? Een korte zoektocht op Google-afbeeldingen met de zoekterm ‘pile of books’ heeft een verbijsterend resultaat: het allereerste plaatje dat verschijnt is de afbeelding op Hebben en houden. De vormgeefster van het boek heeft dus tien seconden geïnvesteerd in het zoeken naar een omslagillustratie voor een boek over, onder andere, bibliofilie. Als dat geen boekenliefde is.

De blurb van het boek zegt dit: ‘Honderdduizend suikerzakjes, dertigduizend boeken, twintigduizend T-shirts, ruim tienduizend bierblikjes, zesduizend uilen en bijna negentig paar sneakers. Er wordt wat verzameld in Nederland.’ En we weten meteen wat voor soort verzamelaars Berveling op het oog heeft. De ‘dertigduizend boeken’ zijn die van Martin Ros, die natuurlijk ook even voorbijkomt, net als, uiteraard, Boudewijn Büch, ‘de bekendste Nederlandse bibliofiel en verzamelaar van de 20ste eeuw’.

Maar is Ros, was Büch een verzamelaar? Büch leek mij toch, net als in alles wat hij deed, een poseur, en zijn boeken waren het perperdure decor van de zoveelste pose. En Martin Ros kan ik sinds een televisieportret lang geleden niet anders meer zien dan met een plastic tasje met boeken voor een garagebox met duizenden van dat soort tasjes ruw en willekeurig opgestapeld. En dan lijkt hij meer op de geciteerde vergaarder van de tienduizend bierblikjes, die daar ongetwijfeld net zo lang – en misschien wel minder chaotisch – over kan vertellen als Ros over boeken. Of op de verzamelaar van xtc-pillen die onlangs in het nieuws was omdat zijn collectie (2400 verschillende) werd gestolen. Als dat eerder was gebeurd, had hij ongetwijfeld in Hebben en houden gestaan.

Bervelings profiel van de verzamelaar is dit: een malloot, een seksueel gefrustreerde gek met een slecht huwelijk en een nog slechtere vaderbinding, die daarnaast lijdt aan een genetisch bepaalde Hollandse schraapkoorts en bovendien aan een neurologische afwijking die hem obsessief allerlei spullen zijn huis in laat slepen totdat hij geen poot meer kan verzetten. Berveling is een socioloog, en de lezer moet dan ook de indruk krijgen dat dit een wetenschappelijk boek is. Een lange bibliografie en interessanterige bronvermeldingen als ‘Hendrikse, 1995:17’ (Berveling, 2009:129) moeten ons laten denken dat hier gedegen onderzoek is gedaan.

Maar ik geloof er niets van: er is vooral verzameld, krantenknipsels namelijk, over mensen die aan Bervelings profiel voldoen. Echte verzamelaars, mensen met een wetenschappelijke insteek bijvoorbeeld die met hun verzamelingen bijdragen aan onze kennis van boeken, kunst en geschiedenis, komen in het boek nauwelijks aan bod. En natuurlijk worden weer de verzamelevergreens gedraaid: Gerard Reve, de Klondykes van Hermans, en ook de pop-upboeken-verzamelaar duikt op, die elk en elk jaar weer door elke journalist geïnterviewd wordt tijdens de boekenmarkt in Deventer.

In een kadertje (Berveling 2009:146) geeft de auteur antwoord op de vraag: ‘Hoe wordt dit boek wat waard?’ ‘Wat’ het boek eventueel waard wordt komen we overigens niet te weten, maar dat zal wel komen omdat er ‘iets’ had moeten staan: ‘Hoe wordt dit boek iets waard?’ dus. Het eerste advies is: ‘Zorg dat u de eerste druk bemachtigt’. Dat is een vreemde raad in deze eerste druk, want die heb ik al. Het tweede advies luidt: ‘Laat de auteur het boek signeren (geen probleem, ik doe dat voor u)’. Afgezien van het praktische probleem van dit aanbod als de koper in Steenoven woont en de auteur in Gaarkeuken: Berveling weet niet dat een gesigneerd boek maar heel zelden een meerwaarde heeft. Tenzij het, bijvoorbeeld, is opgedragen aan iemand die een vervelend stukje over het boek in kwestie schrijft. Ten derde: ‘Let op dat het boek in prima staat blijft’. Dat is een advies om het boek nooit meer te lezen, maar dat lijkt mij geen probleem. En tenslotte: houd trends en modes in de gaten en heb geduld, en ooit zal dat boek van die Berveling veel geld waard zijn. Zou het humor zijn?

Ergens in het boek (Berveling 2009:?) noemt de auteur een verzamelaar met een speciale collectie: vervelende boeken. Die heeft vast nog wel een plekje in zijn kast.

(http://sites.google.com/site/hebbenishouden/)

Jan Gielkens over bibliofiele vondsten en typografische bijzonderheden

Eerder gepubliceerd op: www.teksteditie.org

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Jan Gielkens, The Art of Reading

Märchen der Brüder Grimm

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863)

& Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859)

Der Grabhügel

Ein reicher Bauer stand eines Tages in seinem Hof und schaute nach seinen Feldern und Gärten: das Korn wuchs kräftig heran und die Obstbäume hingen voll Früchte. Das Getreide des vorigen Jahrs lag noch in so mächtigen Haufen auf dem Boden, daß es kaum die Balken tragen konnten. Dann ging er in den Stall, da standen die gemästeten Ochsen, die fetten Kühe und die spiegelglatten Pferde. Endlich ging er in seine Stube zurück und warf seine Blicke auf die eisernen Kasten, in welchen sein Geld lag. Als er so stand und seinen Reichtum übersah, klopfte es auf einmal heftig bei ihm an. Es klopfte aber nicht an die Türe seiner Stube, sondern an die Türe seines Herzens. Sie tat sich auf und er hörte eine Stimme, die zu ihm sprach ‘hast du den Deinigen damit wohlgetan? hast du die Not der Armen angesehen? hast du mit den Hungrigen dein Brot geteilt? war dir genug, was du besaßest, oder hast du noch immer mehr verlangt?’ Das Herz zögerte nicht mit der Antwort ‘ich bin hart und unerbittlich gewesen und habe den Meinigen niemals etwas Gutes erzeigt. Ist ein Armer gekommen, so habe ich mein Auge weggewendet. Ich habe mich um Gott nicht bekümmert, sondern nur an die Mehrung meines Reichtums gedacht. Wäre alles mein eigen gewesen, was der Himmel bedeckte, dennoch hätte ich nicht genug gehabt.’ Als er diese Antwort vernahm, erschrak er heftig: die Knie fingen an ihm zu zittern und er mußte sich niedersetzen. Da klopfte es abermals an, aber es klopfte an die Türe seiner Stube. Es war sein Nachbar, ein armer Mann, der ein Häufchen Kinder hatte, die er nicht mehr sättigen konnte. ‘Ich weiß,’ dachte der Arme, ‘mein Nachbar ist reich, aber er ist ebenso hart: ich glaube nicht, daß er mir hilft, aber meine Kinder schreien nach Brot, da will ich es wagen.’ Er sprach zu dem Reichen ‘Ihr gebt nicht leicht etwas von dem Eurigen weg, aber ich stehe da wie einer, dem das Wasser bis an den Kopf geht: meine Kinder hungern , leiht mir vier Malter Korn.’ Der Reiche sah ihn lange an, da begann der erste Sonnenstrahl der Milde einen Tropfen von dem Eis der Habsucht abzuschmelzen. ‘Vier Malter will ich dir nicht leihen,’ antwortete er, ‘sondern achte will ich dir schenken, aber eine Bedingung mußt du erfüllen.’ ‘Was soll ich tun?, sprach der Arme. ‘Wenn ich tot bin, sollst du drei Nächte an meinem Grabe wachen.’ Dem Bauer ward bei dem Antrag unheimlich zumut, doch in der Not, in der er sich befand, hätte er alles bewilligt: er sagte also zu und trug das Korn heim.

Es war, als hätte der Reiche vorausgesehen, was geschehen würde, nach drei Tagen fiel er plötzlich tot zur Erde; man wußte nicht recht, wie es zugegangen war, aber niemand trauerte um ihn. Als er bestattet war, fiel dem Armen sein Versprechen ein: gerne wäre er davon entbunden gewesen, aber er dachte ‘er hat sich gegen dich doch mildtätig erwiesen, du hast mit seinem Korn deine hungrigen Kinder gesättigt, und wäre das auch nicht, du hast einmal das Versprechen gegeben und mußt du es halten.’ Bei einbrechender Nacht ging er auf den Kirchhof und setzte sich auf den Grabhügel. Es war alles still, nur der Mond schien über die Grabhügel, und manchmal flog eine Eule vorbei und ließ ihre kläglichen Töne hören. Als die Sonne aufging, begab sich der Arme ungefährdet heim, und ebenso ging die zweite Nacht ruhig vorüber. Den Abend des dritten Tags empfand er eine besondere Angst, es war ihm, als stände noch etwas bevor. Als er hinauskam, erblickte er an der Mauer des Kirchhofs einen Mann, den er noch nie gesehen hatte. Er war nicht mehr jung, hatte Narben im Gesicht, und seine Augen blickten scharf und feurig umher. Er war ganz von einem alten Mantel bedeckt, und nur große Reiterstiefeln waren sichtbar. ‘Was sucht Ihr hier?’ redete ihn der Bauer an, ‘gruselt Euch nicht auf dem einsamen Kirchhof?, ‘Ich suche nichts,’ antwortete er, ‘aber ich fürchte auch nichts. Ich bin wie der Junge, der ausging, das Gruseln zu lernen, und sich vergeblich bemühte, der aber bekam die Königstochter zur Frau und mit ihr große Reichtümer, und ich bin immer arm geblieben. Ich bin nichts als ein abgedankter Soldat und will hier die Nacht zubringen, weil ich sonst kein Obdach habe.’ ‘Wenn Ihr keine Furcht habt,’ sprach der Bauer, ‘so bleibt bei mir und helft mir dort den Grabhügel bewachen.’ ‘Wacht halten ist Sache des Soldaten,’ antwortete er, ‘was uns hier begegnet, Gutes oder Böses, das wollen wir gemeinsc haftlich tragen.’ Der Bauer schlug ein, und sie setzten sich zusammen auf das Grab.

Alles blieb still bis Mitternacht, da ertönte auf einmal ein schneidendes Pfeifen in der Luft, und die beiden Wächter erblickten den Bösen, der leibhaftig vor ihnen stand. ‘Fort, ihr Halunken,’ rief er ihnen zu, ‘der in dem Grab liegt, ist mein: ich will ihn holen, und wo ihr nicht weggeht, dreh ich euch die Hälse um.’ ‘Herr mit der roten Feder,’ sprach der Soldat, ‘Ihr seid mein Hauptmann nicht, ich brauch Euch nicht zu gehorchen, und das Fürchten hab ich noch nicht gelernt. Geht Eurer Wege, wir bleiben hier sitzen.’ Der Teufel dachte ‘mit Gold fängst du die zwei Haderlumpen am besten,’ zog gelindere Saiten auf und fragte ganz zutraulich, ob sie nicht einen Beutel mit Gold annehmen und damit heimgehen wollten. ‘Das läßt sich hören,’ antwortete der Soldat, ‘aber mit einem Beutel voll Gold ist uns nicht gedient: wenn Ihr so viel Gold geben wollt, als da in einen von meinen Stiefeln geht, so wollen wir Euch das Feld räumen und abziehen.’ ‘So viel habe ich nicht bei mir,’ sagte der Teufel, ‘aber ich will es holen: in der benachbarten Stadt wohnt ein Wechsler, der mein guter Freund ist, der streckt mir gerne so viel vor.’ Als der Teufel verschwunden war, zog der Soldat seinen linken Stiefel aus und sprach ‘dem Kohlenbrenner wollen wir schon eine Nase drehen: gebt mir nur Euer Messer, Gevatter.’ Er schnitt von dem Stiefel die Sohle ab und stellte ihn neben den Hügel in das hohe Gras an den Rand einer halb überwachsenen Grube. ‘So ist alles gut’ sprach er, ‘nun kann der Schornsteinfeger kommen.’

Beide setzten sich und warteten, es dauerte nicht lange, so kam der Teufel und hatte ein Säckchen Gold in der Hand. ‘Schüttet es nur hinein,’ sprach der Soldat und hob den Stiefel ein wenig in die Höhe, ‘das wird aber nicht genug sein.’ Der Schwarze leerte das Säckchen, das Gold fiel durch und der Stiefel blieb leer. ‘Dummer Teufel,’ rief der Soldat, ‘es schickt nicht: habe ich es nicht gleich gesagt? kehrt nur wieder um und holt mehr.’ Der Teufel schüttelte den Kopf, ging und kam nach einer Stunde mit einem viel größeren Sack unter dem Arm. ‘Nur eingefüllt,’ rief der Soldat, ‘aber ich zweifle, daß der Stiefel voll wird.’ Das Gold klingelte, als es hinabfiel, und der Stiefel blieb leer. Der Teufel blickte mit seinen glühenden Augen selbst hinein und überzeugte sich von der Wahrheit. ‘Ihr habt unverschämt starke Waden,’ rief er und verzog den Mund. ‘Meint Ihr,’ erwiderte der Soldat, ‘ich hätte einen Pferdefuß wie Ihr? seit wann seid Ihr so knauserig? macht, daß Ihr mehr Gold herbeischafft, sonst wird aus unserm Handel nichts.’ Der Unhold trollte sich abermals fort. Diesmal blieb er länger aus, und als er endlich erschien, keuchte er unter der Last eines Sackes, der auf seiner Schulter lag. Er schüttete ihn in den Stiefel, der sich aber so wenig füllte als vorher. Er ward wütend und wollte dem Soldat den Stiefel aus der Hand reißen, aber in dem Augenblick drang der erste Strahl der aufgehenden Sonne am Himmel herauf, und der böse Geist entfloh mit lautem Geschrei. Die arme Seele war gerettet.

Der Bauer wollte das Gold teilen, aber der Soldat sprach ‘gib den Armen, was mir zufällt: ich ziehe zu dir in deine Hütte, und wir wollen mit dem übrigen in Ruhe und Frieden zusammen leben, solange es Gott gefällt.’

ENDE

Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Grimm, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

.jpg)

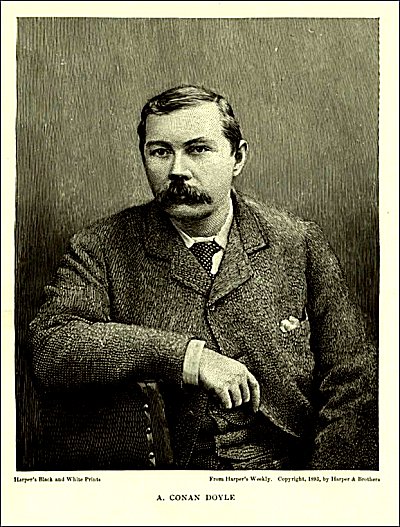

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809-1849)

Von Kempelen and his Discovery

After the very minute and elaborate paper by Arago, to say nothing of the summary in ‘Silliman’s Journal,’ with the detailed statement just published by Lieutenant Maury, it will not be supposed, of course, that in offering a few hurried remarks in reference to Von Kempelen’s discovery, I have any design to look at the subject in a scientific point of view. My object is simply, in the first place, to say a few words of Von Kempelen himself (with whom, some years ago, I had the honor of a slight personal acquaintance), since every thing which concerns him must necessarily, at this moment, be of interest; and, in the second place, to look in a general way, and speculatively, at the results of the discovery.

It may be as well, however, to premise the cursory observations which I have to offer, by denying, very decidedly, what seems to be a general impression (gleaned, as usual in a case of this kind, from the newspapers), viz.: that this discovery, astounding as it unquestionably is, is unanticipated.

By reference to the ‘Diary of Sir Humphrey Davy’ (Cottle and Munroe, London, pp. 150), it will be seen at pp. 53 and 82, that this illustrious chemist had not only conceived the idea now in question, but had actually made no inconsiderable progress, experimentally, in the very identical analysis now so triumphantly brought to an issue by Von Kempelen, who although he makes not the slightest allusion to it, is, without doubt (I say it unhesitatingly, and can prove it, if required), indebted to the ‘Diary’ for at least the first hint of his own undertaking.

The paragraph from the ‘Courier and Enquirer,’ which is now going the rounds of the press, and which purports to claim the invention for a Mr. Kissam, of Brunswick, Maine, appears to me, I confess, a little apocryphal, for several reasons; although there is nothing either impossible or very improbable in the statement made. I need not go into details. My opinion of the paragraph is founded principally upon its manner. It does not look true. Persons who are narrating facts, are seldom so particular as Mr. Kissam seems to be, about day and date and precise location. Besides, if Mr. Kissam actually did come upon the discovery he says he did, at the period designated — nearly eight years ago — how happens it that he took no steps, on the instant, to reap the immense benefits which the merest bumpkin must have known would have resulted to him individually, if not to the world at large, from the discovery? It seems to me quite incredible that any man of common understanding could have discovered what Mr. Kissam says he did, and yet have subsequently acted so like a baby — so like an owl — as Mr. Kissam admits that he did. By-the-way, who is Mr. Kissam? and is not the whole paragraph in the ‘Courier and Enquirer’ a fabrication got up to ‘make a talk’? It must be confessed that it has an amazingly moon-hoaxy-air. Very little dependence is to be placed upon it, in my humble opinion; and if I were not well aware, from experience, how very easily men of science are mystified, on points out of their usual range of inquiry, I should be profoundly astonished at finding so eminent a chemist as Professor Draper, discussing Mr. Kissam’s (or is it Mr. Quizzem’s?) pretensions to the discovery, in so serious a tone.

But to return to the ‘Diary’ of Sir Humphrey Davy. This pamphlet was not designed for the public eye, even upon the decease of the writer, as any person at all conversant with authorship may satisfy himself at once by the slightest inspection of the style. At page 13, for example, near the middle, we read, in reference to his researches about the protoxide of azote: ‘In less than half a minute the respiration being continued, diminished gradually and were succeeded by analogous to gentle pressure on all the muscles.’ That the respiration was not ‘diminished,’ is not only clear by the subsequent context, but by the use of the plural, ‘were.’ The sentence, no doubt, was thus intended: ‘In less than half a minute, the respiration [being continued, these feelings] diminished gradually, and were succeeded by [a sensation] analogous to gentle pressure on all the muscles.’ A hundred similar instances go to show that the MS. so inconsiderately published, was merely a rough note-book, meant only for the writer’s own eye, but an inspection of the pamphlet will convince almost any thinking person of the truth of my suggestion. The fact is, Sir Humphrey Davy was about the last man in the world to commit himself on scientific topics. Not only had he a more than ordinary dislike to quackery, but he was morbidly afraid of appearing empirical; so that, however fully he might have been convinced that he was on the right track in the matter now in question, he would never have spoken out, until he had every thing ready for the most practical demonstration. I verily believe that his last moments would have been rendered wretched, could he have suspected that his wishes in regard to burning this ‘Diary’ (full of crude speculations) would have been unattended to; as, it seems, they were. I say ‘his wishes,’ for that he meant to include this note-book among the miscellaneous papers directed ‘to be burnt,’ I think there can be no manner of doubt. Whether it escaped the flames by good fortune or by bad, yet remains to be seen. That the passages quoted above, with the other similar ones referred to, gave Von Kempelen the hint, I do not in the slightest degree question; but I repeat, it yet remains to be seen whether this momentous discovery itself (momentous under any circumstances) will be of service or disservice to mankind at large. That Von Kempelen and his immediate friends will reap a rich harvest, it would be folly to doubt for a moment. They will scarcely be so weak as not to ‘realize,’ in time, by large purchases of houses and land, with other property of intrinsic value.

In the brief account of Von Kempelen which appeared in the ‘Home Journal,’ and has since been extensively copied, several misapprehensions of the German original seem to have been made by the translator, who professes to have taken the passage from a late number of the Presburg ‘Schnellpost.’ ‘Viele’ has evidently been misconceived (as it often is), and what the translator renders by ‘sorrows,’ is probably ‘lieden,’ which, in its true version, ‘sufferings,’ would give a totally different complexion to the whole account; but, of course, much of this is merely guess, on my part.

Von Kempelen, however, is by no means ‘a misanthrope,’ in appearance, at least, whatever he may be in fact. My acquaintance with him was casual altogether; and I am scarcely warranted in saying that I know him at all; but to have seen and conversed with a man of so prodigious a notoriety as he has attained, or will attain in a few days, is not a small matter, as times go.

‘The Literary World’ speaks of him, confidently, as a native of Presburg (misled, perhaps, by the account in ‘The Home Journal’) but I am pleased in being able to state positively, since I have it from his own lips, that he was born in Utica, in the State of New York, although both his parents, I believe, are of Presburg descent. The family is connected, in some way, with Maelzel, of Automaton-chess-player memory. In person, he is short and stout, with large, fat, blue eyes, sandy hair and whiskers, a wide but pleasing mouth, fine teeth, and I think a Roman nose. There is some defect in one of his feet. His address is frank, and his whole manner noticeable for bonhomie. Altogether, he looks, speaks, and acts as little like ‘a misanthrope’ as any man I ever saw. We were fellow-sojouners for a week about six years ago, at Earl’s Hotel, in Providence, Rhode Island; and I presume that I conversed with him, at various times, for some three or four hours altogether. His principal topics were those of the day, and nothing that fell from him led me to suspect his scientific attainments. He left the hotel before me, intending to go to New York, and thence to Bremen; it was in the latter city that his great discovery was first made public; or, rather, it was there that he was first suspected of having made it. This is about all that I personally know of the now immortal Von Kempelen; but I have thought that even these few details would have interest for the public.

There can be little question that most of the marvellous rumors afloat about this affair are pure inventions, entitled to about as much credit as the story of Aladdin’s lamp; and yet, in a case of this kind, as in the case of the discoveries in California, it is clear that the truth may be stranger than fiction. The following anecdote, at least, is so well authenticated, that we may receive it implicitly.

Von Kempelen had never been even tolerably well off during his residence at Bremen; and often, it was well known, he had been put to extreme shifts in order to raise trifling sums. When the great excitement occurred about the forgery on the house of Gutsmuth & Co., suspicion was directed toward Von Kempelen, on account of his having purchased a considerable property in Gasperitch Lane, and his refusing, when questioned, to explain how he became possessed of the purchase money. He was at length arrested, but nothing decisive appearing against him, was in the end set at liberty. The police, however, kept a strict watch upon his movements, and thus discovered that he left home frequently, taking always the same road, and invariably giving his watchers the slip in the neighborhood of that labyrinth of narrow and crooked passages known by the flash name of the ‘Dondergat.’ Finally, by dint of great perseverance, they traced him to a garret in an old house of seven stories, in an alley called Flatzplatz, — and, coming upon him suddenly, found him, as they imagined, in the midst of his counterfeiting operations. His agitation is represented as so excessive that the officers had not the slightest doubt of his guilt. After hand-cuffing him, they searched his room, or rather rooms, for it appears he occupied all the mansarde.

Opening into the garret where they caught him, was a closet, ten feet by eight, fitted up with some chemical apparatus, of which the object has not yet been ascertained. In one corner of the closet was a very small furnace, with a glowing fire in it, and on the fire a kind of duplicate crucible — two crucibles connected by a tube. One of these crucibles was nearly full of lead in a state of fusion, but not reaching up to the aperture of the tube, which was close to the brim. The other crucible had some liquid in it, which, as the officers entered, seemed to be furiously dissipating in vapor. They relate that, on finding himself taken, Kempelen seized the crucibles with both hands (which were encased in gloves that afterwards turned out to be asbestic), and threw the contents on the tiled floor. It was now that they hand-cuffed him; and before proceeding to ransack the premises they searched his person, but nothing unusual was found about him, excepting a paper parcel, in his coat-pocket, containing what was afterward ascertained to be a mixture of antimony and some unknown substance, in nearly, but not quite, equal proportions. All attempts at analyzing the unknown substance have, so far, failed, but that it will ultimately be analyzed, is not to be doubted.

Passing out of the closet with their prisoner, the officers went through a sort of ante-chamber, in which nothing material was found, to the chemist’s sleeping-room. They here rummaged some drawers and boxes, but discovered only a few papers, of no importance, and some good coin, silver and gold. At length, looking under the bed, they saw a large, common hair trunk, without hinges, hasp, or lock, and with the top lying carelessly across the bottom portion. Upon attempting to draw this trunk out from under the bed, they found that, with their united strength (there were three of them, all powerful men), they ‘could not stir it one inch.’ Much astonished at this, one of them crawled under the bed, and looking into the trunk, said:

‘No wonder we couldn’t move it — why it’s full to the brim of old bits of brass!’ Putting his feet, now, against the wall so as to get a good purchase, and pushing with all his force, while his companions pulled with an theirs, the trunk, with much difficulty, was slid out from under the bed, and its contents examined. The supposed brass with which it was filled was all in small, smooth pieces, varying from the size of a pea to that of a dollar; but the pieces were irregular in shape, although more or less flat-looking, upon the whole, ‘very much as lead looks when thrown upon the ground in a molten state, and there suffered to grow cool.’ Now, not one of these officers for a moment suspected this metal to be any thing but brass. The idea of its being gold never entered their brains, of course; how could such a wild fancy have entered it? And their astonishment may be well conceived, when the next day it became known, all over Bremen, that the ‘lot of brass’ which they had carted so contemptuously to the police office, without putting themselves to the trouble of pocketing the smallest scrap, was not only gold — real gold — but gold far finer than any employed in coinage-gold, in fact, absolutely pure, virgin, without the slightest appreciable alloy.

I need not go over the details of Von Kempelen’s confession (as far as it went) and release, for these are familiar to the public. That he has actually realized, in spirit and in effect, if not to the letter, the old chimaera of the philosopher’s stone, no sane person is at liberty to doubt. The opinions of Arago are, of course, entitled to the greatest consideration; but he is by no means infallible; and what he says of bismuth, in his report to the Academy, must be taken cum grano salis. The simple truth is, that up to this period all analysis has failed; and until Von Kempelen chooses to let us have the key to his own published enigma, it is more than probable that the matter will remain, for years, in statu quo. All that as yet can fairly be said to be known is, that ‘Pure gold can be made at will, and very readily from lead in connection with certain other substances, in kind and in proportions, unknown.’

Speculation, of course, is busy as to the immediate and ultimate results of this discovery — a discovery which few thinking persons will hesitate in referring to an increased interest in the matter of gold generally, by the late developments in California; and this reflection brings us inevitably to another — the exceeding inopportuneness of Von Kempelen’s analysis. If many were prevented from adventuring to California, by the mere apprehension that gold would so materially diminish in value, on account of its plentifulness in the mines there, as to render the speculation of going so far in search of it a doubtful one — what impression will be wrought now, upon the minds of those about to emigrate, and especially upon the minds of those actually in the mineral region, by the announcement of this astounding discovery of Von Kempelen? a discovery which declares, in so many words, that beyond its intrinsic worth for manufacturing purposes (whatever that worth may be), gold now is, or at least soon will be (for it cannot be supposed that Von Kempelen can long retain his secret), of no greater value than lead, and of far inferior value to silver. It is, indeed, exceedingly difficult to speculate prospectively upon the consequences of the discovery, but one thing may be positively maintained — that the announcement of the discovery six months ago would have had material influence in regard to the settlement of California.

In Europe, as yet, the most noticeable results have been a rise of two hundred per cent. in the price of lead, and nearly twenty-five per cent. that of silver.

Edgar Allan Poe: Von Kempelen and his Discovery

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Chess in literature, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

.jpg)

Pietro Aretino (1492 – 1556)

painted by

Titian (ca 1480 – 1576)

fleursdumal.nl

More in: Aretino, Pietro, Erotic literature, Poets' Portraits

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

I n a L i b r a r y

A precious, mouldering pleasure ‘t is

To meet an antique book,

In just the dress his century wore;

A privilege, I think,

His venerable hand to take,

And warming in our own,

A passage back, or two, to make

To times when he was young.

His quaint opinions to inspect,

His knowledge to unfold

On what concerns our mutual mind,

The literature of old;

What interested scholars most,

What competitions ran

When Plato was a certainty.

And Sophocles a man;

When Sappho was a living girl,

And Beatrice wore

The gown that Dante deified.

Facts, centuries before,

He traverses familiar,

As one should come to town

And tell you all your dreams were true;

He lived where dreams were sown.

His presence is enchantment,

You beg him not to go;

Old volumes shake their vellum heads

And tantalize, just so.

.jpg)

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Dickinson, Emily, Libraries in Literature

.jpg)

.jpg)

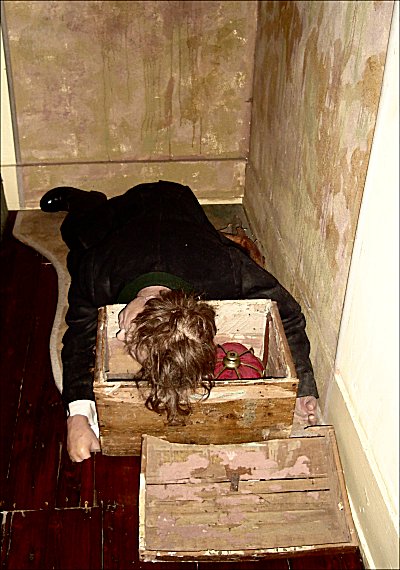

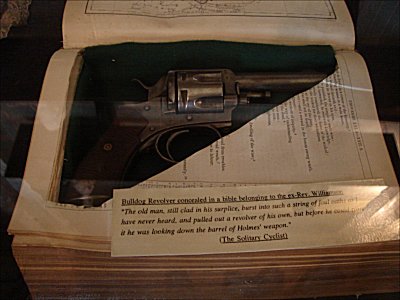

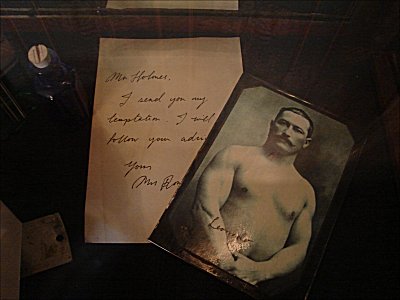

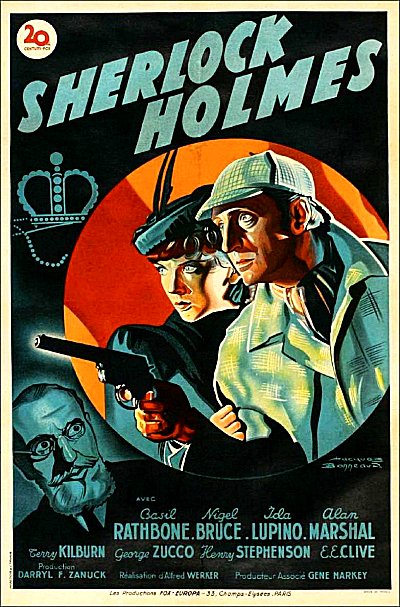

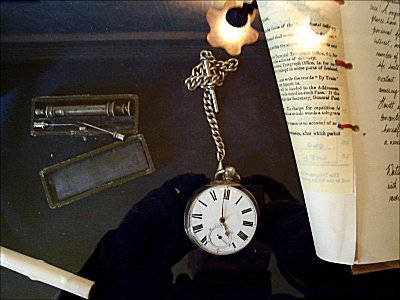

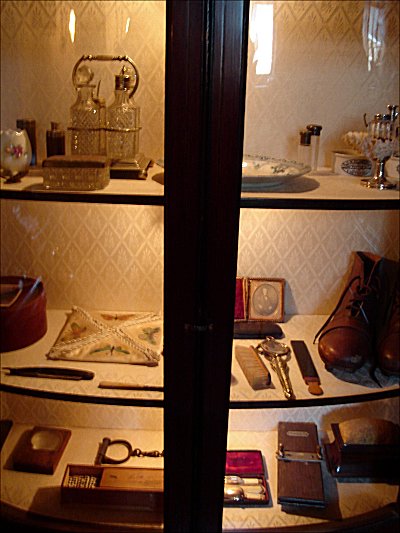

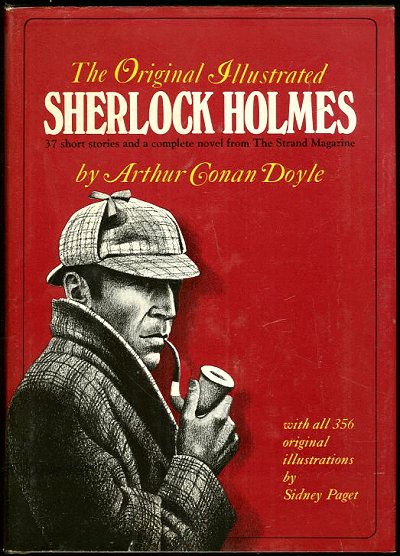

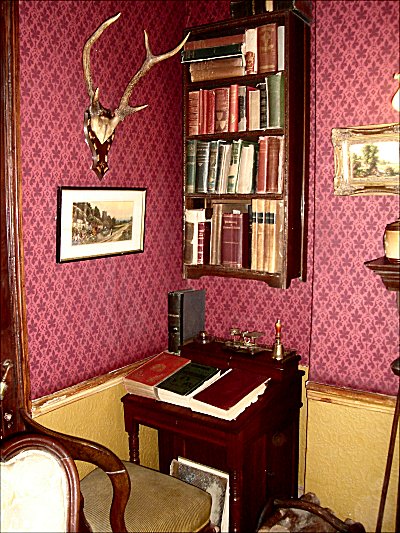

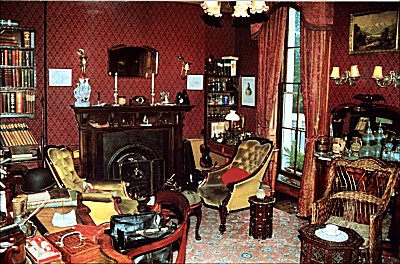

Museum of Literary Treasures

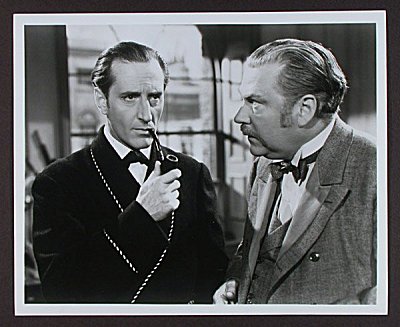

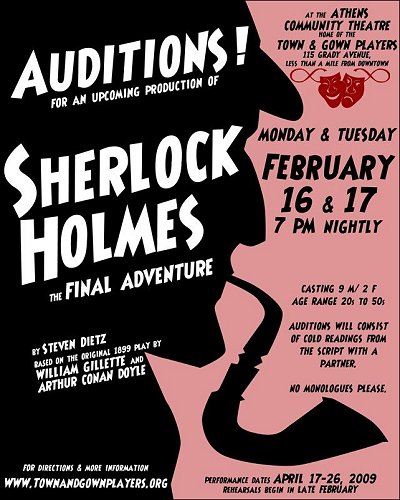

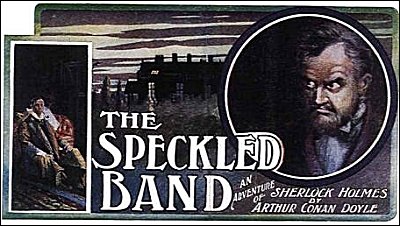

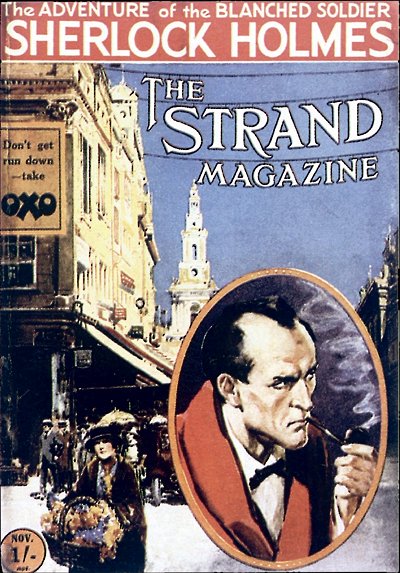

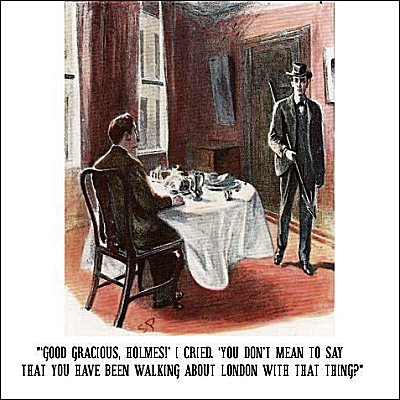

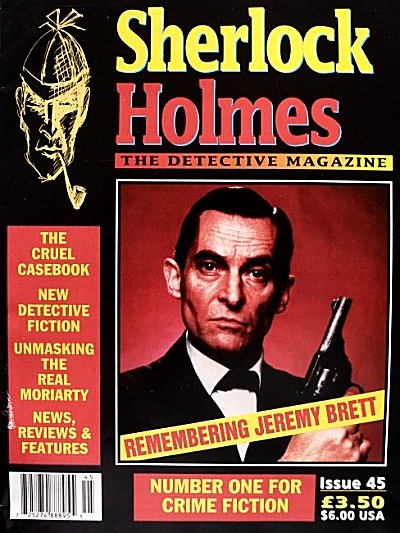

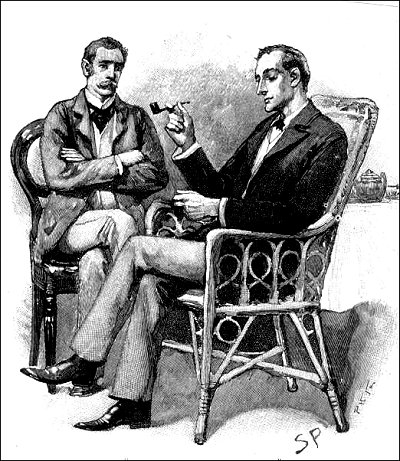

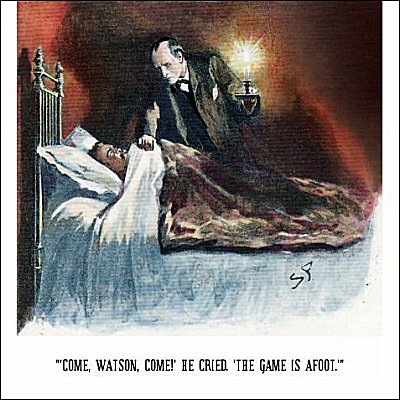

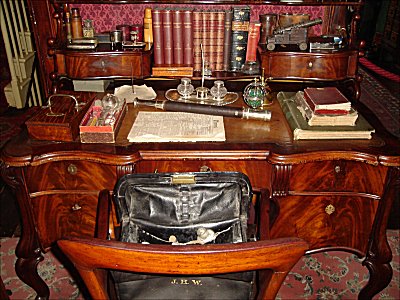

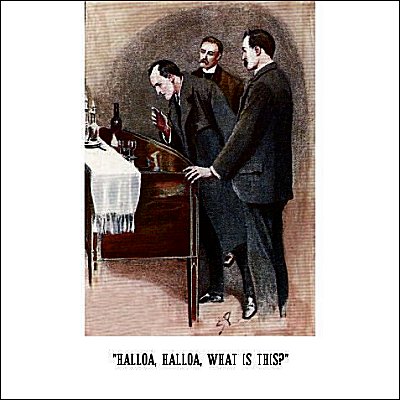

SHERLOCK HOLMES part VI

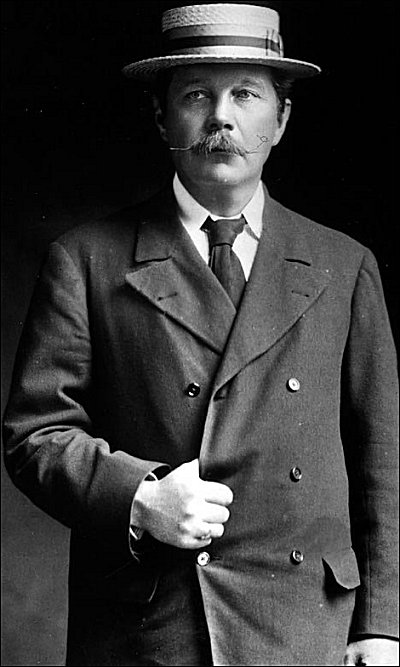

The Sherlock Holmes Museum

Bakerstreet – LONDON

.jpg)

photos: jefvankempen

Illustrations: Sidney Paget

FLEURSDUMAL.NL MAGAZINE

More in: Arthur Conan Doyle, Illustrators, Illustration, Museum of Literary Treasures, Sherlock Holmes Theatre

.jpg)

.jpg)

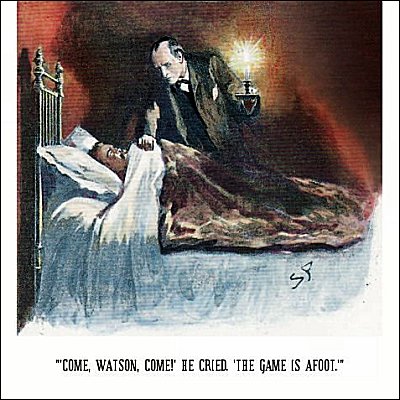

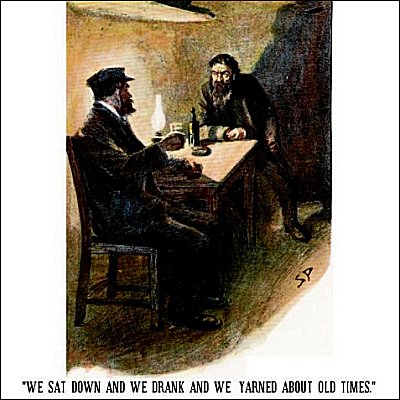

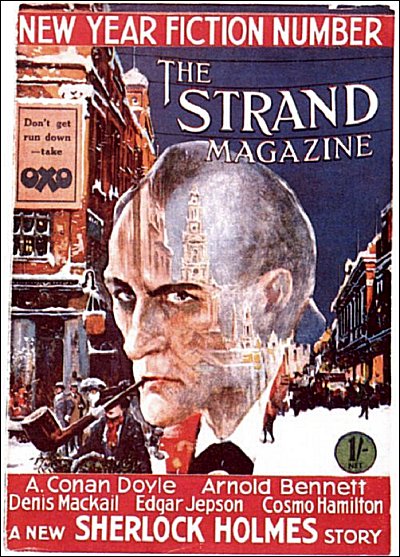

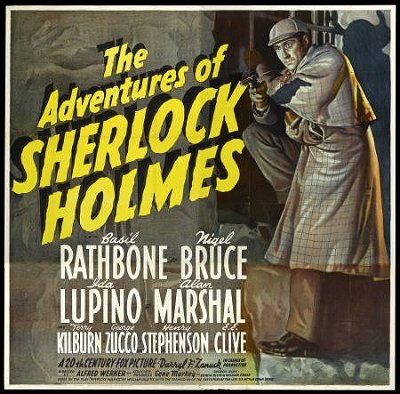

Museum of Literary Treasures

SHERLOCK HOLMES part V

The Sherlock Holmes Museum

Bakerstreet – LONDON

.jpg)

photos: jefvankempen

Illustrations: Sidney Paget

FLEURSDUMAL.NL MAGAZINE

More in: Arthur Conan Doyle, Museum of Literary Treasures, Sherlock Holmes Theatre

.jpg)

.jpg)

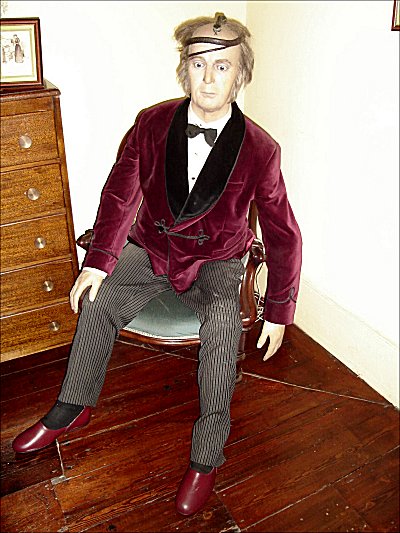

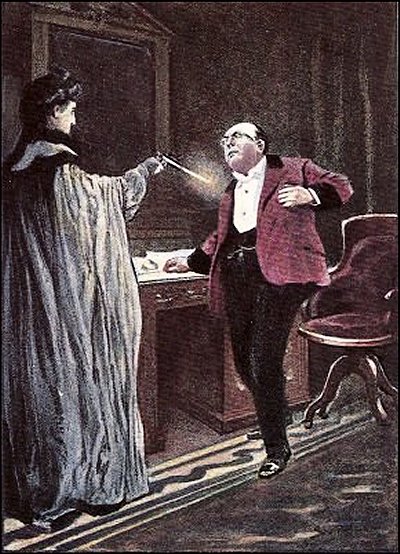

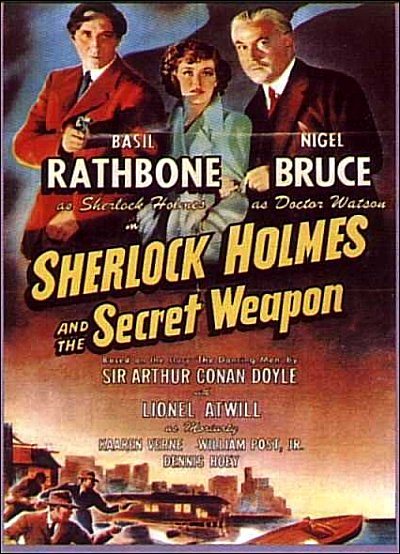

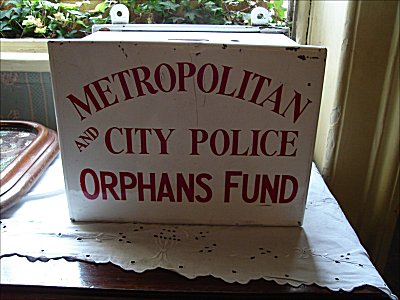

Museum of Literary Treasures

SHERLOCK HOLMES part IV

The Sherlock Holmes Museum

Bakerstreet – LONDON

.jpg)

photos: jefvankempen

Illustrations: Sidney Paget

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Arthur Conan Doyle, Museum of Literary Treasures, Sherlock Holmes Theatre

.jpg)

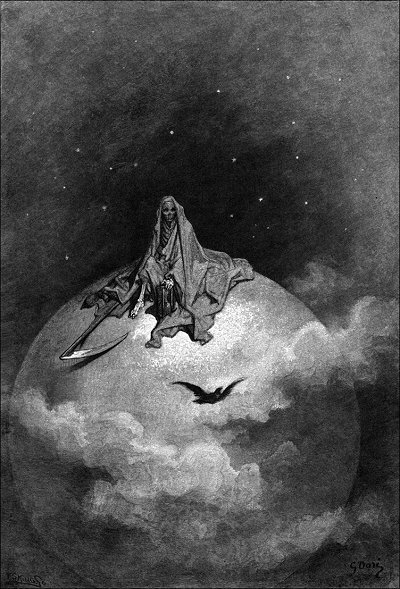

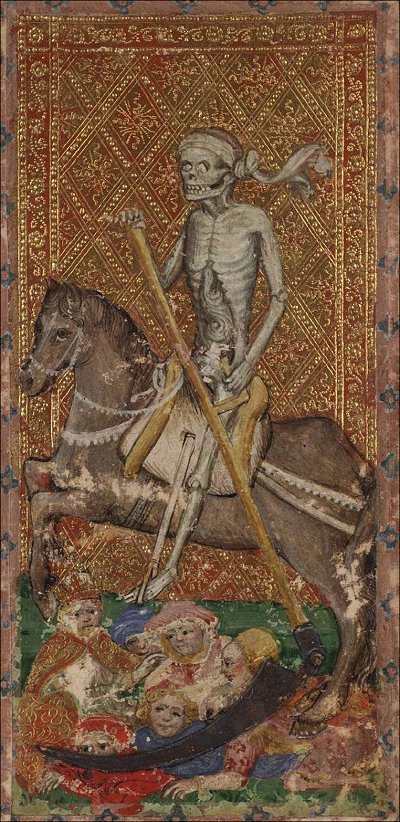

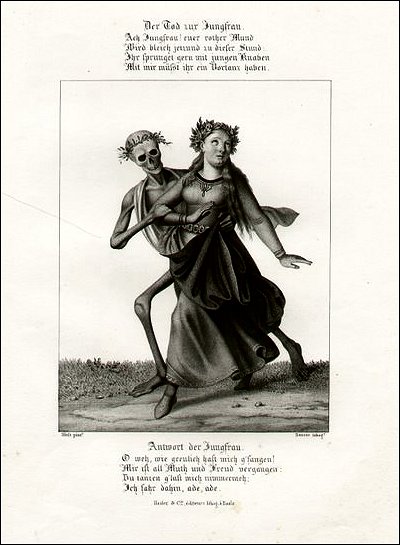

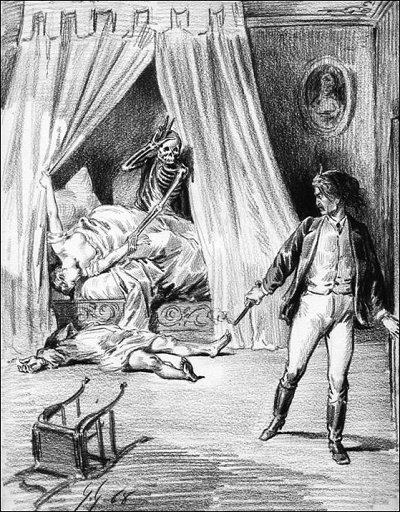

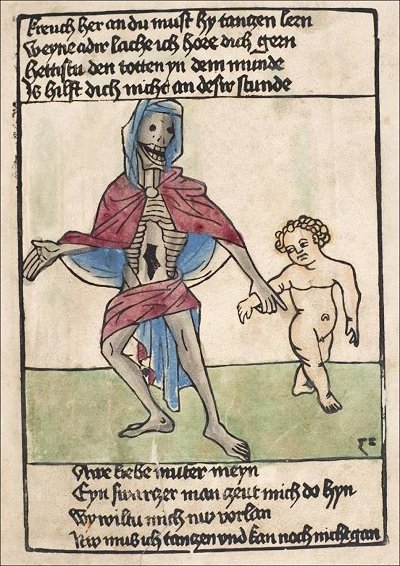

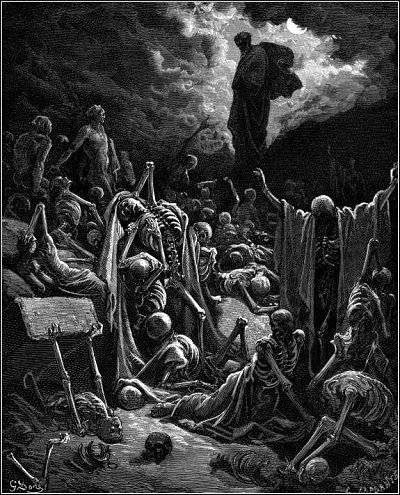

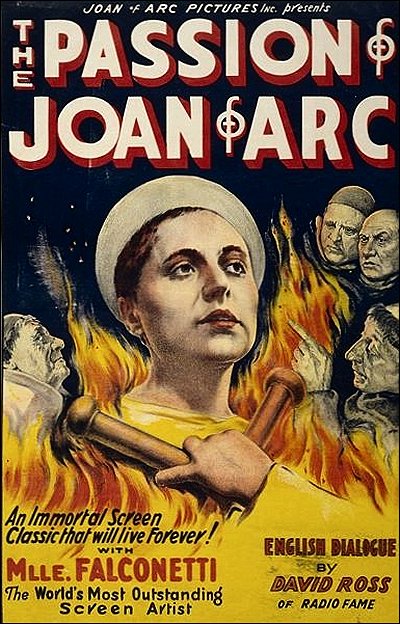

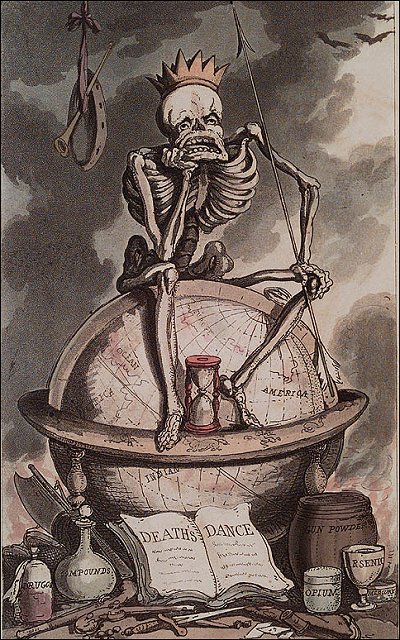

Memento Mori IV

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Danse Macabre

.jpg)

.jpg)

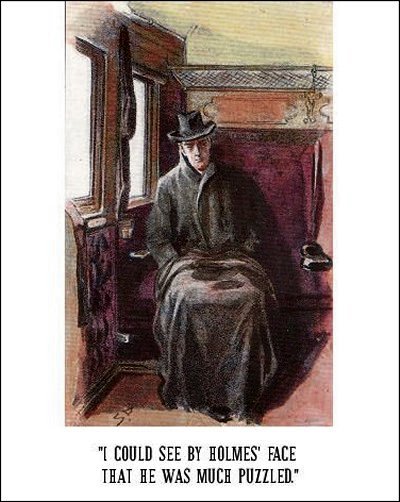

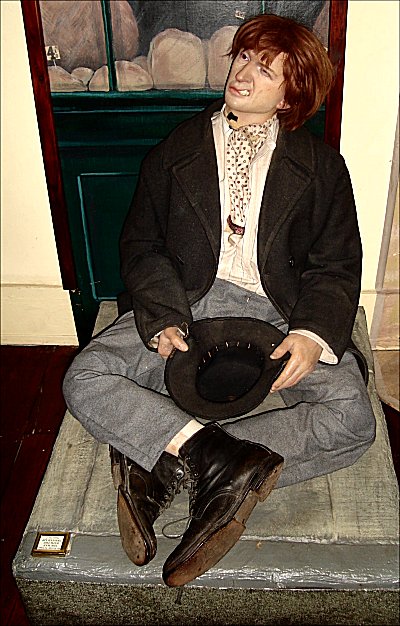

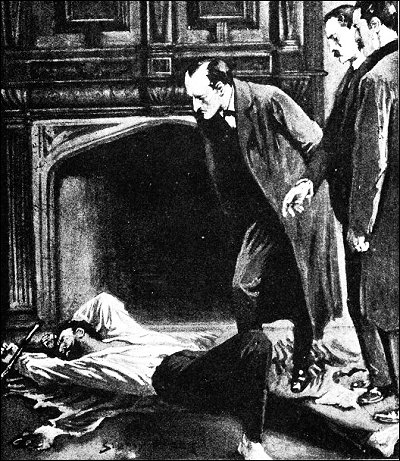

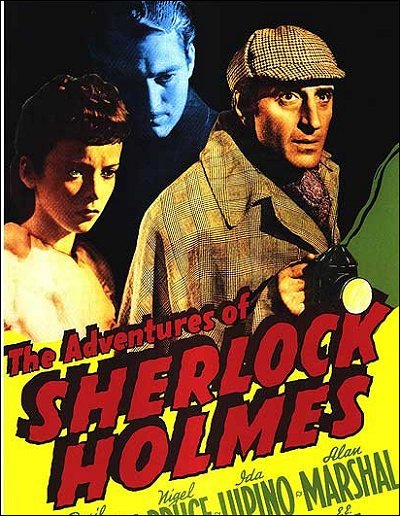

Museum of Literary Treasures

SHERLOCK HOLMES part III

The Sherlock Holmes Museum

Bakerstreet – LONDON

![]()

photos: jefvankempen

Illustrations: Sidney Paget

FLEURSDUMAL.NL MAGAZINE

More in: Arthur Conan Doyle, Museum of Literary Treasures, Sherlock Holmes Theatre

.jpg)

.jpg)

Museum of Literary Treasures

SHERLOCK HOLMES part II

The Sherlock Holmes Museum

Bakerstreet – LONDON

![]()

photos: jefvankempen

Illustrations: Sidney Paget

FLEURSDUMAL.NL MAGAZINE

More in: Arthur Conan Doyle, Museum of Literary Treasures, Sherlock Holmes Theatre

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature