Paul Laurence Dunbar : The Scapegoat (II). Short story

THE SCAPEGOAT (II)

A year is not a long time. It was short enough to prevent people from forgetting Robinson, and yet long enough for their pity to grow strong as they remembered. Indeed, he was not gone a year. Good behaviour cut two months off the time of his sentence, and by the time people had come around to the notion that he was really the greatest and smartest man in Cadgers he was at home again.

He came back with no flourish of trumpets, but quietly, humbly. He went back again into the heart of the black district. His business had deteriorated during his absence, but he put new blood and new life into it. He did not go to work in the shop himself, but, taking down the shingle that had swung idly before his office door during his imprisonment, he opened the little room as a news- and cigar-stand.

He came back with no flourish of trumpets, but quietly, humbly. He went back again into the heart of the black district. His business had deteriorated during his absence, but he put new blood and new life into it. He did not go to work in the shop himself, but, taking down the shingle that had swung idly before his office door during his imprisonment, he opened the little room as a news- and cigar-stand.

Here anxious, pitying custom came to him and he prospered again. He was very quiet. Uptown hardly knew that he was again in Cadgers, and it knew nothing whatever of his doings.

“I wonder why Asbury is so quiet,” they said to one another. “It isn’t like him to be quiet.” And they felt vaguely uneasy about him.

So many people had begun to say, “Well, he was a mighty good fellow after all.”

Mr. Bingo expressed the opinion that Asbury was quiet because he was crushed, but others expressed doubt as to this. There are calms and calms, some after and some before the storm. Which was this?

They waited a while, and, as no storm came, concluded that this must be the after-quiet. Bingo, reassured, volunteered to go and seek confirmation of this conclusion.

He went, and Asbury received him with an indifferent, not to say, impolite, demeanour.

“Well, we’re glad to see you back, Asbury,” said Bingo patronisingly. He had variously demonstrated his inability to lead during his rival’s absence and was proud of it. “What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to work.”

“That’s right. I reckon you’ll stay out of politics.”

“What could I do even if I went in?”

“Nothing now, of course; but I didn’t know—-“

He did not see the gleam in Asbury’s half shut eyes. He only marked his humility, and he went back swelling with the news.

“Completely crushed–all the run taken out of him,” was his report.

The black district believed this, too, and a sullen, smouldering anger took possession of them. Here was a good man ruined. Some of the people whom he had helped in his former days–some of the rude, coarse people of the low quarter who were still sufficiently unenlightened to be grateful–talked among themselves and offered to get up a demonstration for him. But he denied them. No, he wanted nothing of the kind. It would only bring him into unfavourable notice. All he wanted was that they would always be his friends and would stick by him.

They would to the death.

There were again two factions in Cadgers. The school-master could not forget how once on a time he had been made a tool of by Mr. Bingo. So he revolted against his rule and set himself up as the leader of an opposing clique. The fight had been long and strong, but had ended with odds slightly in Bingo’s favour.

But Mr. Morton did not despair. As the first of January and Emancipation Day approached, he arrayed his hosts, and the fight for supremacy became fiercer than ever. The school-teacher is giving you a pretty hard brought the school-children in for chorus singing, secured an able orator, and the best essayist in town. With all this, he was formidable.

Mr. Bingo knew that he had the fight of his life on his hands, and he entered with fear as well as zest. He, too, found an orator, but he was not sure that he was as good as Morton’s. There was no doubt but that his essayist was not. He secured a band, but still he felt unsatisfied. He had hardly done enough, and for the school-master to beat him now meant his political destruction.

It was in this state of mind that he was surprised to receive a visit from Mr. Asbury.

“I reckon you’re surprised to see me here,” said Asbury, smiling.

“I am pleased, I know.” Bingo was astute.

“Well, I just dropped in on business.”

“To be sure, to be sure, Asbury. What can I do for you?”

“It’s more what I can do for you that I came to talk about,” was the reply.

“I don’t believe I understand you.”

“Well, it’s plain enough. They say that the school-teacher is giving you a pretty hard fight.”

“Oh, not so hard.”

“No man can be too sure of winning, though. Mr. Morton once did me a mean turn when he started the faction against me.”

Bingo’s heart gave a great leap, and then stopped for the fraction of a second.

“You were in it, of course,” pursued Asbury, “but I can look over your part in it in order to get even with the man who started it.”

It was true, then, thought Bingo gladly. He did not know. He wanted revenge for his wrongs and upon the wrong man. How well the schemer had covered his tracks! Asbury should have his revenge and Morton would be the sufferer.

“Of course, Asbury, you know what I did I did innocently.”

“Oh, yes, in politics we are all lambs and the wolves are only to be found in the other party. We’ll pass that, though. What I want to say is that I can help you to make your celebration an overwhelming success. I still have some influence down in my district.”

“Certainly, and very justly, too. Why, I should be delighted with your aid. I could give you a prominent place in the procession.”

“I don’t want it; I don’t want to appear in this at all. All I want is revenge. You can have all the credit, but let me down my enemy.”

Bingo was perfectly willing, and, with their heads close together, they had a long and close consultation. When Asbury was gone, Mr. Bingo lay back in his chair and laughed. “I’m a slick duck,” he said.

From that hour Mr. Bingo’s cause began to take on the appearance of something very like a boom. More bands were hired. The interior of the State was called upon and a more eloquent orator secured. The crowd hastened to array itself on the growing side.

With surprised eyes, the school-master beheld the wonder of it, but he kept to his own purpose with dogged insistence, even when he saw that he could not turn aside the overwhelming defeat that threatened him. But in spite of his obstinacy, his hours were dark and bitter. Asbury worked like a mole, all underground, but he was indefatigable. Two days before the celebration time everything was perfected for the biggest demonstration that Cadgers had ever known. All the next day and night he was busy among his allies.

On the morning of the great day, Mr. Bingo, wonderfully caparisoned, rode down to the hall where the parade was to form. He was early. No one had yet come. In an hour a score of men all told had collected. Another hour passed, and no more had come. Then there smote upon his ear the sound of music. They were coming at last. Bringing his sword to his shoulder, he rode forward to the middle of the street. Ah, there they were. But–but–could he believe his eyes? They were going in another direction, and at their head rode–Morton! He gnashed his teeth in fury. He had been led into a trap and betrayed. The procession passing had been his–all his. He heard them cheering, and then, oh! climax of infidelity, he saw his own orator go past in a carriage, bowing and smiling to the crowd.

There was no doubting who had done this thing. The hand of Asbury was apparent in it. He must have known the truth all along, thought Bingo. His allies left him one by one for the other hall, and he rode home in a humiliation deeper than he had ever known before.

Asbury did not appear at the celebration. He was at his little news-stand all day.

In a day or two the defeated aspirant had further cause to curse his false friend. He found that not only had the people defected from him, but that the thing had been so adroitly managed that he appeared to be in fault, and three-fourths of those who knew him were angry at some supposed grievance. His cup of bitterness was full when his partner, a quietly ambitious man, suggested that they dissolve their relations.

His ruin was complete.

The lawyer was not alone in seeing Asbury’s hand in his downfall. The party managers saw it too, and they met together to discuss the dangerous factor which, while it appeared to slumber, was so terribly awake. They decided that he must be appeased, and they visited him.

He was still busy at his news-stand. They talked to him adroitly, while he sorted papers and kept an impassive face. When they were all done, he looked up for a moment and replied, “You know, gentlemen, as an ex-convict I am not in politics.”

Some of them had the grace to flush.

“But you can use your influence,” they said.

“I am not in politics,” was his only reply.

And the spring elections were coming on. Well, they worked hard, and he showed no sign. He treated with neither one party nor the other. “Perhaps,” thought the managers, “he is out of politics,” and they grew more confident.

It was nearing eleven o’clock on the morning of election when a cloud no bigger than a man’s hand appeared upon the horizon. It came from the direction of the black district. It grew, and the managers of the party in power looked at it, fascinated by an ominous dread. Finally it began to rain Negro voters, and as one man they voted against their former candidates. Their organisation was perfect. They simply came, voted, and left, but they overwhelmed everything. Not one of the party that had damned Robinson Asbury was left in power save old Judge Davis. His majority was overwhelming.

The generalship that had engineered the thing was perfect. There were loud threats against the newsdealer. But no one bothered him except a reporter. The reporter called to see just how it was done. He found Asbury very busy sorting papers. To the newspaper man’s questions he had only this reply, “I am not in politics, sir.”

But Cadgers had learned its lesson.

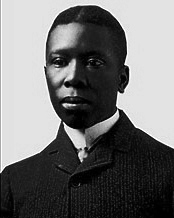

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Scapegoat (II)

Short story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar