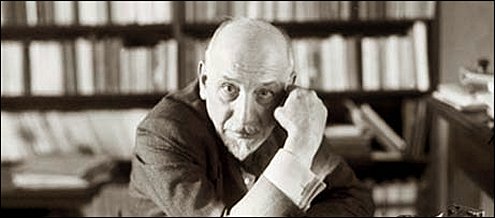

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (16)

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (16)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff.

BOOK III

5

It is no mere waste of time, you will understand, to spend half an hour in watching and considering a tiger, seeing in it a manifestation of Earth, guileless, beyond good and evil, incomparably beautiful and innocent in its savage power. Before we can come down from this “aboriginality” and reach the stage of being able to see before us a man or woman of our own time, and to recognise and consider him or her as an inhabitant of the same earth, we require–I do, at least; I cannot answer for you–a wide stretch of imagination.

And so I remained for a while looking at Signora Nestoroff before I was able to understand what she was saying to me.

But the fault, as a matter of fact, was not only mine and the tiger’s. The fact of her addressing me at all was unusual; and it is quite natural, when anyone addresses us suddenly with whom we have not been on speaking terms, that we should find it hard at first to take in the meaning, sometimes even the sound of the most ordinary words, and should ask:

“Excuse me, what was it you said?”

In a little more than eight months, since I came here, between her and myself, apart from formal greetings, barely a score of words have passed.

Then she–yes, this happened too–coming up to me, began to speak to me with great volubility, as we do when we wish to distract the attention of some one who has caught us in some action or thought which we are anxious to keep secret. (The Nestoroff speaks our language with marvellous ease and with a perfect accent, as though she had lived for many years in Italy: but she at once breaks into French whenever, if only for a moment, she changes her tone or grows excited.) She wished to find out from me whether I believed that the actor’s profession was such that any animal whatsoever (not necessarily in a metaphorical sense) could regard itself as qualified, without preliminary training, to practise it.

“Where?” I asked her.

She did not understand my question.

“Well,” I explained to her; “if you mean, practise it here, where there is no need of speech, perhaps even an animal–why not!–may be capable of succeeding.”

I saw her face cloud over.

“That will be it,” she said mysteriously.

I seemed at first to divine that she (like all the professional actors who are employed here) speaking out of contempt for certain others who, without actually needing, but at the same time not despising an easy source of revenue, either from vanity or from predilection, or for some other reason, had managed to have their services accepted by the firm and to take their place among the actors, with no great difficulty, that supreme difficulty being eliminated which it would have been most arduous for them and perhaps impossible to overcome without a long training and a genuine aptitude, I mean the difficulty of speaking in public. We have a number of them at the Kosmograph who are real gentlemen, young fellows between twenty and thirty, either friends of some big shareholder on the Board, or shareholders themselves, who make a hobby of playing some part or other that has taken their fancy in a film, solely for their own amusement; and play their parts in the most gentlemanly fashion, some of them even with a grace that a real actor might envy.

But, reflecting afterwards on the mysterious tone in which she, her face suddenly clouding over, had uttered the words: “That will be it,” the suspicion occurred to me that perhaps she had heard the news that Aldo Nuti, I do not yet know from what part of the horizon, was trying to find an opening here.

This suspicion disturbed me not a little.

Why did she come to ask me, of all people, with Aldo Nuti in her mind, whether I believed that the actor’s profession was such that any animal might consider itself qualified, without preliminary training, to practise it? Did she then know of my friendship with Giorgio Mirelli?

I had not then, nor have I now any reason to think so. At least the questions with which I have adroitly plied her in the hope of enlightenment have brought me no certainty.

I do not know why, but I should dislike intensely her knowing that I was a friend of Giorgio Mirelli, in his boyhood, and a familiar inmate of the villa by Sorrento into which she brought confusion and death.

“I do not know why,” I have said: but it is not true; I do know why, and I have already given a hint of the reason. I feel no love, I repeat again, nor could I feel any, for this woman; hatred, if anything. Everyone hates her here; and that by itself would be an overwhelming reason for me not to hate her. Always, in judging other people, I have endeavoured to break the circle of my own affections, to gather from the clamour of life, composed more of tears than of laughter, as many notes as I could outside the chord of my own feelings. I knew Giorgio Mirelli; but how, in what capacity? Such as he was in his relations with me. He was the sort of person that I liked. But who, and what was he in his relations with this woman? The sort that she could like? I do not know. Certainly he was not, he could not be one and the same person to her and to myself. And how then am I to judge this woman by him? We have all of us a false conception of an individual whole. Every whole consists in the mutual relations of its constituent elements; which means that, by altering those relations however slightly, we are bound to alter the whole. This explains how some one who is reasonably loved by me can reasonably be hated by a third person. I who love and the other who hates are two: not only that, but the one whom I love, and the one whom the third person hates, are by no means identical; they are one and one: therefore they are two also. And we ourselves can never know what reality is accorded to us by other people; who we are to this person and to that.

Now, if the Nesteroff came to hear that I had been a great friend of Giorgio Mirelli, she would perhaps suspect me of a hatred for herself which I do not feel: and this suspicion would be enough to make her at once become another person to me, I myself remaining meanwhile in the same attitude towards her; she would assume in my eyes an aspect that would hide all the rest; and I should no longer be able to study her,as I am now studying her, as a whole.

I spoke to her of the tiger, of the feelings which its presence in this place and the fate in store for it aroused in me; but I at once became aware that she was not in a position to understand me, not perhaps because she was incapable of doing so, but because the relations that have grown up between her and the animal do not allow her to feel either pity for it or anger at the deed that is to be done.

Her answer was shrewd:

“A sham, yes; stupid too, if you like; but when the door of the cage is opened and the animal is driven into the other, bigger cage representing a glade in a forest, with the bars hidden by branches, the hunter, even if he is a sham like the forest, will still be entitled to defend himself against it, simply because it, as you say, is not a sham animal but a real one.”

“But that is just where the harm lies,” I exclaimed: “in using a real animal where everything else is a sham.”

“Where do you get that?” she promptly rejoined. “The part of the hunter will be a sham; but when he is face to face with this ‘real’ animal he will be a ‘real’ man! And I can assure you that if he does not kill it with his first shot, or does not wound it so as to bring it down, it will not stop to think that the hunter is a sham and the hunt a sham, but will spring upon him and ‘really’ tear a ‘real’ man to pieces.”

I smiled at the acuteness of her logic and said:

“But who will have wished such a thing. Look at her as she lies there. She knows nothing, the beautiful creature, she is not to blame for her ferocity.”

There was a strange look in her eyes, as though she suspected that I was trying to make fun of her; then she smiled as well, shrugged her shoulders slightly and went on:

“Do you feel is to deeply! Tame her! Make her a stage tiger, trained to sham death at a sham bullet from a sham hunter, and then all will be right.”

We should never have come to an under-standing; because if my sympathies were with the tiger, hers were with the hunter.

In fact, the hunter appointed to kill the animal is Carlo Ferro. The Nestoroff must be greatly upset by this; and perhaps she comes here not, as her enemies assert, to study her part, but to estimate the risk which her lover will be running.

He too, for all that he shews a scornful indifference, must, in his heart of hearts, feel apprehensive. I know that, in conversation with the General Manager, Commendator Borgalli, and also upstairs in the office, he has put forward a number of claims: the insurance of his life for at least one hundred thousand lire, to be paid to his parents in Sicily, in the event of his death, which heaven forbid; another insurance, for a more modest sum, in the event of his being incapacitated for work by any serious injury, which heaven forbid also; a handsome bonus, if everything, as is to be hoped, turns out well, and lastly–a curious claim, and one that was certainly not suggested, like the rest, by a lawyer–the skin of the dead tiger.

The tigerskin is presumably for the Nestoroff; for her little feet; a costly rug. Oh, she must certainly have warned her lover, with prayers and entreaties, against undertaking so dangerous a part; but then, seeing him determined and bound by contract, she must, she and no one else, have suggested to Ferro that he should claim ‘at least’ the skin of the tiger. “At least?” you say. Why, yes! That she used the words “at least” seems to me beyond question. ‘At least’, that is to say in compensation for the tense anxiety that she must feel for the risk to which he will be exposing himself. It is not possible that the idea can have originated with him, Carlo Ferro, of having the skin of the dead animal to spread under the little feet of his mistress. Carlo Ferro is incapable of such an idea. You have only to look at him to be convinced of it; look at that great black hairy arrogant goat’s head on his shoulders.

He appeared, the other day, and interrupted my conversation with the Nestoroff in front of the cage. He did not even trouble to inquire what we were discussing, as though a conversation with myself could not be of the slightest importance to him. He barely glanced at me, barely raised Ms bamboo cane to the brim of Ms hat in sign of greeting, looked with Ms usual contemptuous indifference at the tiger in the cage, saying to his mistress:

“Come along: Polacco is ready; he is waiting for us.”

And he turned his back, confident of being followed by the Nestoroff, as a tyrant by Ms slave.

No one feels or shews so much as he that instinctive antipathy, which as I have said is shared by almost all the actors for myself, and which is to be explained, or so at least I explain it, as an effect, which they themselves do not see clearly, of my profession.

Carlo Ferro feels it more strongly than any of them, because, among all his other advantages, he has that of seriously believing himself to be a great actor.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (16)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!