Victoria & Albert Museum London until 17 July 2011 last chance to see THE CULT OF BEAUTY: THE AESTHETIC MOVEMENT 1860-1900

Choosing’- George Frederic Watts – London 1864 – Oil on strawboard – National Portrait Gallery, London – This painting depicts the young actress Ellen Terry reaching out to the opulent but scentless camellia and discarding the common, but fragrant violets in her hand

Victoria & Albert Museum London

until 17 July 2011 last chance to see

THE CULT OF BEAUTY

THE AESTHETIC MOVEMENT 1860-1900

The exhibition has been arranged in four main chronological sections, charting the development of the Aesthetic Movement in art and design through the decades from the 1860s to the 1890s. As well as paintings, prints and drawings, the show will include examples of all the ‘artistic’ decorative arts, together with drawings, designs and photographs, as well as portraits, fashionable dress and jewellery of the era. Literary life will be represented by some of the most beautiful books of the day, whilst a number of set-pieces will reveal the visual world of the Aesthetes, evoking the kind of rooms and ensembles of exquisite objects through which they expressed their sensibilities.

‘Symphony in White, No. 3′- James McNeill Whistler – London 1867 – Oil on canvas – The Trustees of the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham – One critic claimed that this painting was ‘not precisely a symphony in white’ because it also included other colours. Whistler retorted that ‘a symphony in F…contains no other note, but a continued repetition of F, F, F-Fool!’

The search for new beauty

1860s

In the 1860s the new and exciting ‘Cult of Beauty’ united, for a while at least, romantic bohemians such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (and his younger Pre-Raphaelite followers William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones), maverick figures such as James McNeill Whistler, then fresh from Paris and full of ‘dangerous’ French ideas about modern painting, and the ‘Olympians’ – the painters of grand classical subjects who belonged to the circle of Frederic Leighton and G.F.Watts. Choosing unconventional models, such as Rossetti’s muse Lizzie Siddal or Leighton’s sultry favourite ‘La Nanna’, these painters created entirely new types of female beauty.

Rossetti and his friends were also the first to attempt to realise their imaginative world in the creation of ‘artistic’ furniture and the decoration of rooms. In this period, artists’ houses and their extravagant lifestyles became the object of public fascination and sparked a revolution in the architecture and interior decoration of houses that led to a widespread recognition of the need for beauty in everyday life.

Armchair – Lawrence Alma-Tadema – Made by Johnstone, Norman & Co. London 1884-6 – Mahogany, with cedar and ebony veneer, inlay of several woods, ivory and abalone shell – Museum no. W.25:1-1980 – This armchair was designed for a ‘Greek parlour’ and belonged to Henry Gourdon Marquand, the second director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Art for Arts Sake

1870s-1880s

One of the most important examples of the mutual influence between artists and designers is to be found in the startling collaborations between James McNeill Whistler and the architect E.W.Godwin who designed the painter’s studio, The White House, and created some of the most innovative furniture of the day. Characterised equally by elegance and eccentricity, Whistler and Godwin’s work drew upon influences as diverse as ancient Greek art and the Japanese prints and other artifacts just beginning to arrive in Europe.

In the 1870s, the leading Aesthetic artists, Whistler, Leighton, Watts, Albert Moore and Burne-Jones evolved a new kind of self-consciously exquisite painting in which mood, colour harmony and beauty of form were all, and subject played little or no part. The opening of the Grosvenor Gallery (with its famous ‘greenery-yallery’ walls) in 1877 at last gave the Aesthetic painters a fashionable and glamorous showcase for their much-discussed art. But the decade closed with intense controversy exemplified by the critic John Ruskin’s savage attack on Whistler, which prompted the painter’s spirited defence of the ideals of ‘Art for Art’s Sake’ in his writings and by the staging of his own exhibitions.

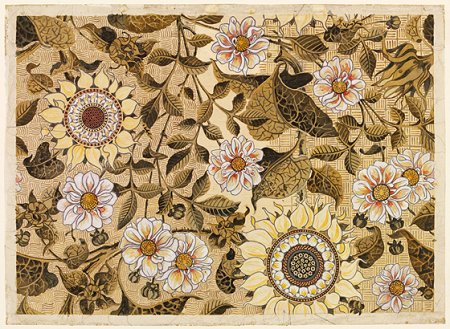

Design for ‘The Sunflower’ wallpaper – Bruce James Talbert – Made by Jeffrey & Co. London 1878 – Watercolour and body colour – Museum no. E.37-1945 Given by Mrs Margaret Warner – The wallpaper manufacturer Jeffrey & Co. employed Aesthetic designers such as Bruce Talbert to bring ‘art’ to their products

Beautiful people and Aesthetic houses

1870s-1880s

The immense success of the Grosvenor Gallery signalled the emergence of a new artistic elite whose social prestige offered an unprecedented challenge to the Royal Academy. Aesthetic painting became the fashionable enthusiasm of a circle that was grand, wealthy and intellectual. As well as buying paintings these new patrons were keen to embrace Aesthetic ideals, commissioning portraits and even adopting the styles of ‘artistic’ dress.

The rise of Aestheticism in painting was paralleled in the decorative arts by a new and increasingly widespread interest in the decoration of houses. Many of the key avant-garde architects and designers interested themselves not only in working for wealthy clients but also in the reform of design for the middle-class home. The notion of ‘The House Beautiful’ became a touchstone of cultured life.

Attracted by the growing popularity of Aesthetic taste, many of the leading firms making furniture, ceramics, domestic metalwork and textiles courted artists such as Walter Crane and a growing band of professional designers, most notably Christopher Dresser. Co-inciding with a period of unprecedented expansion of domestic markets, the styles favoured by Aesthetic designers were among the very first to be exploited and disseminated widely through commercial enterprise.

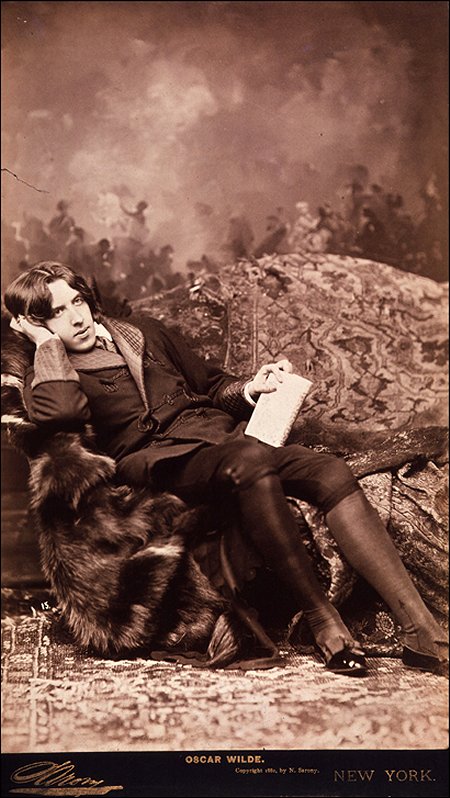

‘Oscar Wilde’ – Napoleon Sarony – New York 1882 – Albumen panel print – National Portrait Gallery, London – Sarony’s photographs, taken at the beginning of Oscar Wilde’s American lecture tour, fixed his image in the public imagination as the epitome of the Aesthete

Late-flowering beauty

1880s-1890s

Oscar Wilde, the first celebrity style-guru, invented a brilliant pose of ‘poetic intensity’, but initially made his name promoting the idea of ‘The House Beautiful’. By the 1880s Britain was in the grip of the ‘greenery-yallery’ Aesthetic Craze, lovingly satirised by Gilbert and Sullivan in their famous comic opera Patience and by the caricaturist George Du Maurier in the pages of Punch.

In the last decade of Queen Victoria’s reign the Aesthetic Movement entered its final, fascinating Decadent phase, characterised by the extraordinary black-and-white drawings of Aubrey Beardsley in The Yellow Book.

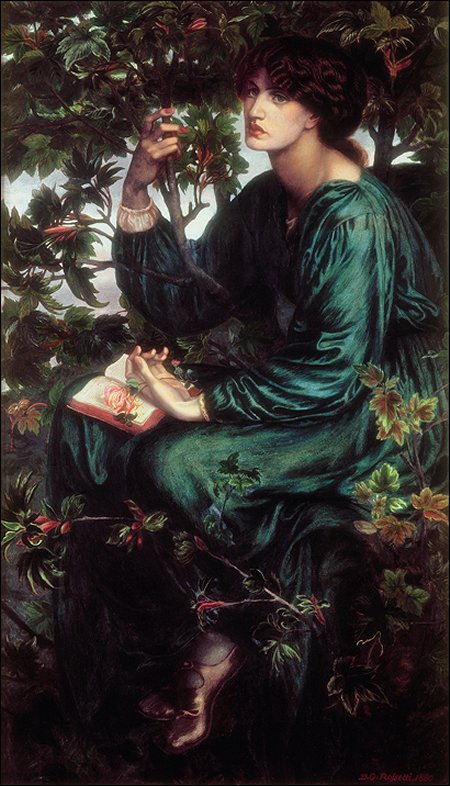

The exhibition ends with a superb group of the greatest late Aesthetic paintings, including masterpieces such as Leighton’s Bath of Psyche, Moore’s Midsummer and Rossetti’s final picture The Daydream, shown alongside the sensuous nude figures sculpted in bronze and precious materials by Alfred Gilbert and other brilliant younger exponents of ‘The New Sculpture’.

‘The Day Dream’ – Dante Gabriel Rossetti – 1880 London – Oil on canvas – Museum no. CAI.3 – Bequeathed by Constantine Alexander Ionides – This is one of the last major oil paintings that Rossetti completed. The lush green leaves match the fullness of Jane Morris’s figure in her green silk dress

Victoria & Albert Museum London

until 17 July 2011 last chance to see

THE CULT OF BEAUTY: THE AESTHETIC MOVEMENT 1860-1900

‘Icarus’ – Alfred Gilbert – Rome and Naples – Cast in the foundry of Sabatino de Angelis 1884 – Bronze – Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales – © National Museum of Wales – Frederic Leighton commissioned Gilbert to produce a bronze statue, leaving him to choose the subject. Gilbert took the mythical figure of Icarus, the ambitious youth who flew too close to the sun

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *The Pre-Raphaelites Archive